Published online Jul 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i13.2787

Peer-review started: March 9, 2020

First decision: April 22, 2020

Revised: June 15, 2020

Accepted: July 1, 2020

Article in press: July 1, 2020

Published online: July 6, 2020

Processing time: 119 Days and 17.6 Hours

Case studies (CS) are relevant for the development of theoretical and practical competencies in psychotherapy. Despite rapid progress in the development of methods and principles for establishing CS in the last three decades, research into the aims of CS, especially in training, or how CS are to be conducted is rare.

To elucidate the form and methodology of CS, the objectives of CS used in training institutions (TI), and if/how TIs handle therapist allegiance. Also, this preliminary investigation will suggest avenues for further research and attempt to establish certain guidelines.

In order to counteract researcher bias and enlarge the question-pool, a focus group was established. The recorded and transcribed text was analyzed with Mayring’s method of qualitative content analysis, and the generated categories were formulated as questions. The resulting questionnaire with both qualitative and quantitative queries was sent out (after pre-testing) to all 39 Austrian TIs that provide professional psychotherapy training. The answers and text passages received were then also categorized with qualitative content analysis. Data analysis was discussed by a peer group consisting of three psychotherapists trained in differing schools of psychotherapeutic methods.

94% of Austrian institutes use CS as part of their psychotherapeutic training. Understanding of the term “case study” is inconsistent and has a wide variety of interpretations. CS serve mainly: (1) For observation of training/progress in therapeutic practice and knowledge/acquisition of the theory specific to each psychotherapeutic school; (2) To improve (self-)reflection capabilities; and (3) To expand theoretical knowledge. Most of the CS written are not accessible for students nor for the research community. More than two thirds of the CS take only the position of the author into account (the client’s position is not described). 15.5 % of the TIs do not consider researcher or therapist allegiance at all.

A more precise formulation of the term case study is needed in psychotherapeutic training. The training therapists play a key function, as they exemplify and teach how to deal with distorting factors. General guidelines as to how to conduct CS in training institutions would provide more direction to students, increase scientific rigor, and enhance synergistic effects.

Core tip: Case studies are commonly used in psychotherapy training for theoretical and practical development of psychotherapeutic competencies. Yet there is hardly any research into if or how clinical case studies are used in training programs. This exploratory study gives the first glimpse into the training landscape in Austria, to our knowledge. Thirty-nine training institutes were investigated, and the results led to the conclusion that further research is necessary in order to define the term “case study” in psychotherapeutic training more precisely, create research-based guidelines for case studies, and deal with bias stemming from school and/or researcher allegiance.

- Citation: Neidhart E, Löffler-Stastka H. Case studies in psychotherapy training using Austria as an example. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(13): 2787-2801

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i13/2787.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i13.2787

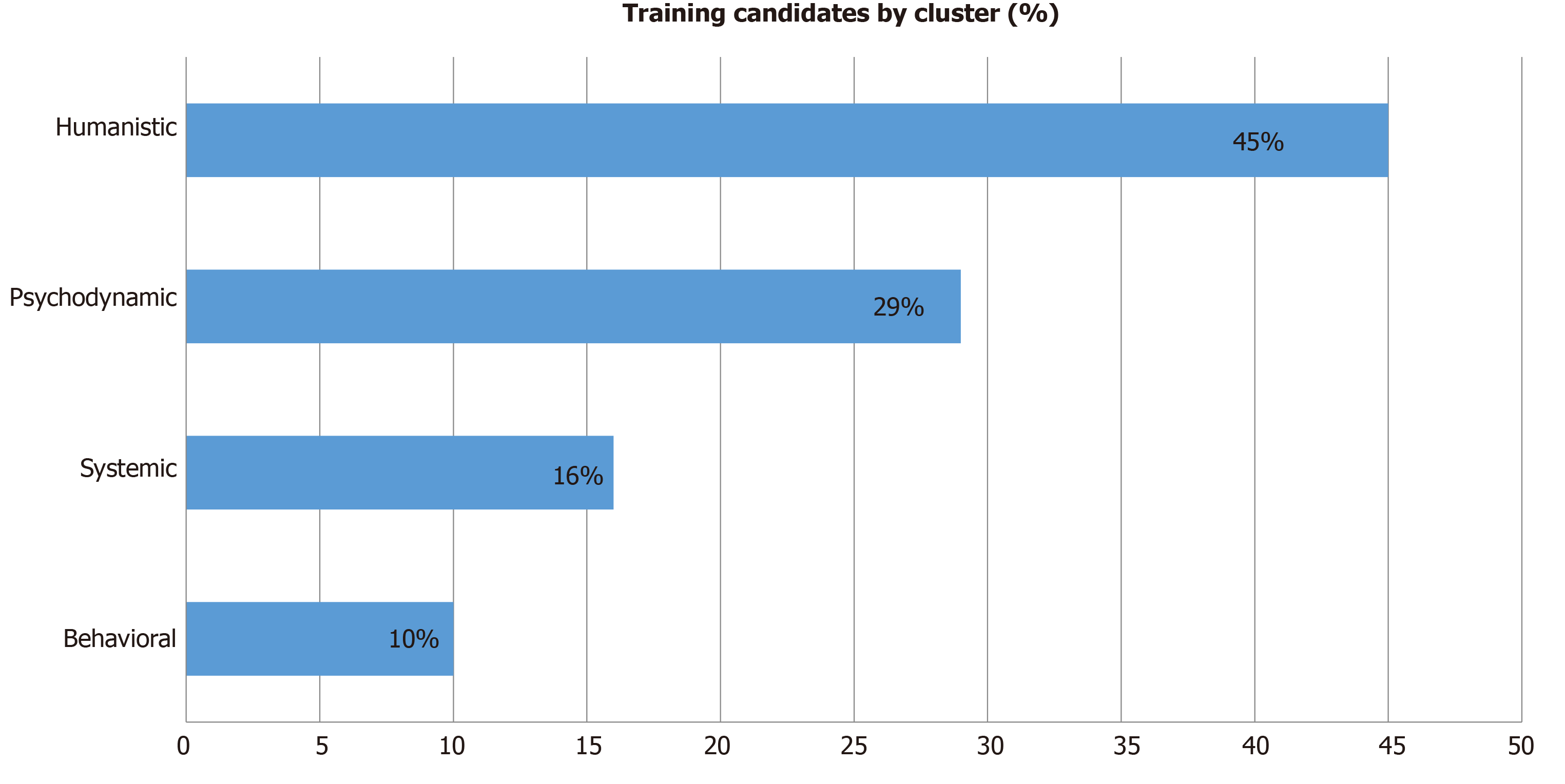

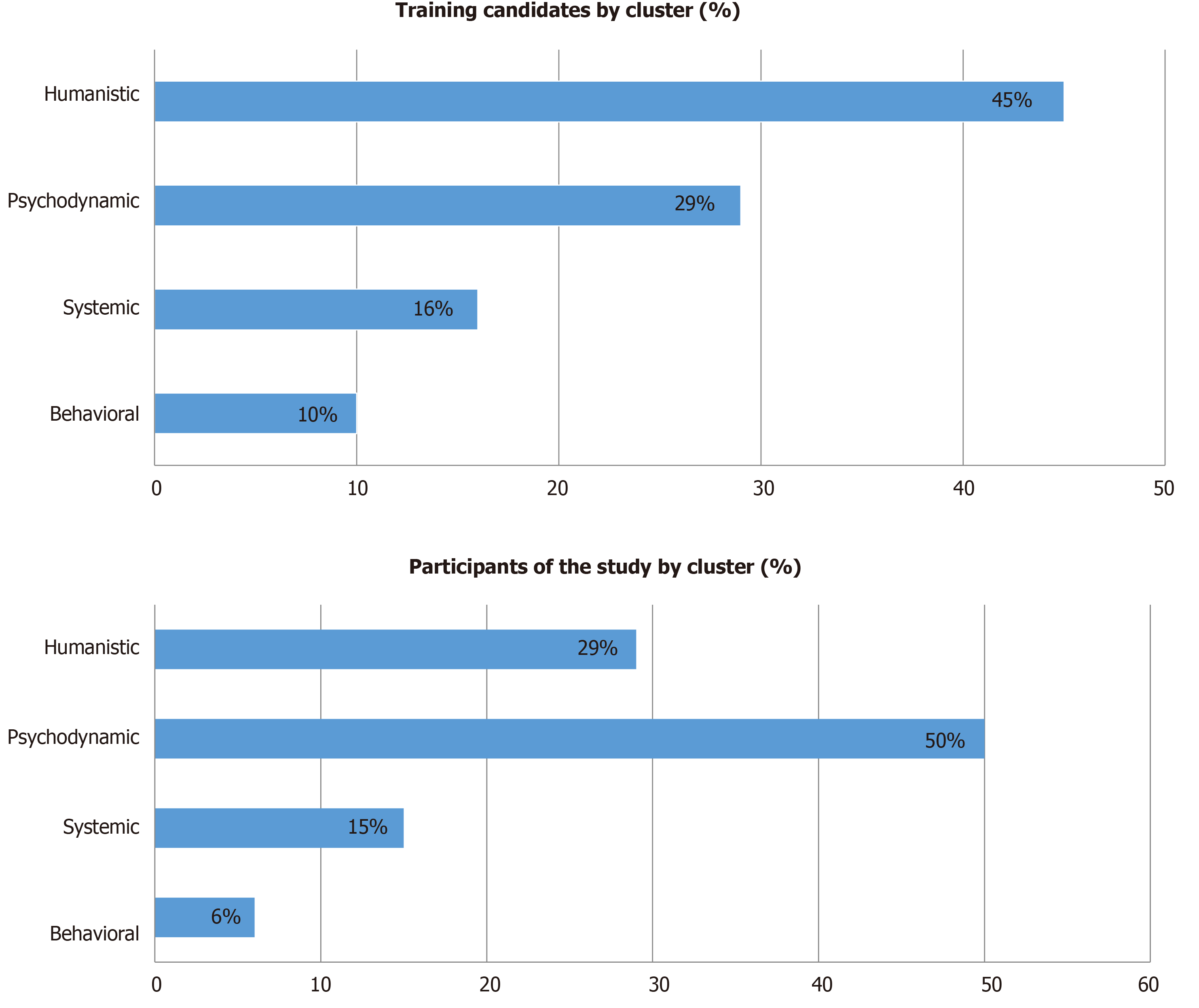

In 2019, 10150 practicing psychotherapists in Austria (source: https://www.psyonline.at/contents/14722/statistik-und-daten-zur-psychotherapie) were registered, and as of 2016, about 3800 trainees[1]. Trainees are trained at 39 (active) different training institutes (TI), most of the students trained in humanistic methods. Number of psychotherapy students in Austria by cluster (from Sagerschnig und Tanios[2]), Figure 1.

In Austria, 23 different specializations are legally recognized (based on the Psychotherapy Act of 1991 and 1994).

In 2012, a coordination center for psychotherapy research was founded in Austria. It considers psychotherapy research as multiparadigmatic and cross-methodological. Quantitative and qualitative research methods are regarded as equivalent, both being meaningful and target-oriented[3]. The short-term objective is, among other things, to increase research activities in TIs by motivating the different TIs to participate; in the long run, the main aim is to obtain more reliable research results through integration of quality-assurance into both practice and training[3].

In the psychotherapeutic community, the relationship between practice-oriented and evidence-based psychotherapy research has long been regarded as antagonistic. Recently, this approach seems to have paved the way for an attitude that considers practice-oriented and evidence-based research as complementary methods with their own strengths and weaknesses, in which both methodological research strategies expand and enrich knowledge about psychotherapy[3-6].

In recent years, meta-analyses and systematic reviews have shown that the influence of researchers’ specific training background (allegiance) has a significant impact on results, including those of randomized controlled trials[7-11].

Dragioti et al[9] systematically investigated whether the allegiance was disclosed in Meta-analysis (MA) and Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs). About 80% of the MA specified researcher allegiance and only 4.1% used a control method. The vast majority of RCTs also rarely collected or reported the effects of allegiance (3.2%), and only 1 study (out of 793 investigated) even considered its effects.

In psychotherapy research, RCTs (the gold standard of study design) continue to show a concomitance of treatment efficacy and therapist efficacy[8]. Even in trials with “crossed” therapists (one therapist being trained in more than one psychotherapy method), researcher allegiance and therapist allegiance where significant confounders. The Meta-analysis conducted by Falkenström et al[8] and his team showed only 1 out of 39 RCTs measuring therapist allegiance. Moreover, only 36% of the trials reviewed mentioned therapist or researcher allegiance. If several therapists with different method-specific training backgrounds work together in so-called “crossed therapist studies” in order to minimize the allegiance bias, the distortions would even multiply. The study also showed that researchers with a training background in behavioral therapy (CBT) described controlling for therapist allegiance less frequently than researchers with a different or no specific psychotherapeutic training background.

Lieb et al[11] complement the discussion with their own systematic review that states that both the inclusion of one’s own previous studies in a systematic review and neglect of therapist allegiance were frequently observed. This significantly distorts the results of the RCTs. In addition, the study illustrates that conflicts of interests are rarely reported (e.g., conflict of financial interest in conducting a study that compares the efficacy of psychotherapy with the efficacy of pharmacological treatment).

Meta-analysis, especially those that compare the strengths of the individual psychotherapeutic disciplines (e.g., CBT with other psychotherapeutic disciplines or methods), also show distortions. In their MA, Munder et al[7] examined 97 studies that compared the efficacy of different psychotherapy methods treating post-traumatic stress disorder and treating depression. Their suspicion was confirmed, that the differences in efficacy found in the studies correlate strongly with the methodological quality of the individual studies; researcher allegiance bias was greater when the methodological quality of the studies evaluated was lower.

Wampold et al[12] showed that the effects demonstrating the superiority of CBT are small, mostly not significant, limited to the targeted symptoms, and often are the results of poorly planned/executed primary studies.

Taking a look at bias in CS with a low level of evidence (e.g. single case studies), we encounter various kinds of bias[13]. Already, the selection of the topic and the hypothesis are subject to distortion due to selection bias, when the researchers choose their case based on their prior knowledge of the case that favors certain hypotheses. This can be counterbalanced by a careful description of the research process (above all by a detailed description of the process of data collection)[14,15] and by traceability, consistency, and disciplined subjectivity[15]. Other distorting influencing factors include, once again, the impact of the specific psychotherapeutic training background (therapist allegiance) and researchers’ affiliation (researcher allegiance). Conflict of interests also plays a role; they are rarely or not at all declared and they do have clear impact on the outcome.

Double evaluation of the results (by a second expert), inclusion of study participants with respect to evaluation[16], and blinded studies[17] are further efforts to minimize distortions of study results.

The present study evaluates the significance of CS in Austrian therapeutic training institutes. This exploratory investigation aims to clarify: (1) The form and methodology of CS; (2) The objectives of CS used in training institutions; (3) Whether the CS are preparing for scientific research; (4) If and how the TI handle therapist allegiance; and (5) If the written CS are accessible to students and researchers. Our hypothesis is that there is no universally accepted meaning of the term case study and that there are great differences between the training institutions.

A discussion with experts (focus group), evaluation of text with qualitative content analysis and a follow-up questionnaire, complemented by a quantitative survey, formed the main methodological instruments of this study.

The expert group served to explore and to broaden possible categories of questions that subsequently would be integrated into the questionnaire sent to the different psychotherapeutic TIs. The focus group used at this early stage of the study was intended to counterbalance the selection bias[13] of the individual researcher. The participants of the focus group assembled consisted of 5 people with different backgrounds of psychotherapeutic methods.

The partially standardized interview of the focus group was evaluated using qualitative content analysis developed by Mayring (Qcamap). The categories determined served as the basis for the questionnaire. The poll included 42 questions, grouped in eight main topics which were drawn from the inductive analysis of the discussion of the focus group. The categories arising from the analysis were: Sociodemographic questions, value of CS in training, aims/use of CS in training, forms/methods of CS in training, formal criteria establishing CS, assessment of CS, accessibility/publication of CS, and dealing with bias in CS (emphasis on school affiliation).

Depending on the question, scaling of the possible answers was nominal, ordinal, by interval, or by ratio scaling. Several questions were multiple choice, the possibilities provided being drawn from the content analysis of the focus group. In addition to these structured multiple-choice options, a free space was offered to give participants the possibility to add whatever they liked that was not mentioned in the presented list.

The ordinal scalings gave four options (yes – rather yes – rather no – no), in order to avoid the tendency of marking the middle (forced choice).

Before sending the final questionnaire to participants, a preliminary draft was sent to five people (psychotherapists and trainers) in order to optimize comprehension of the questions, question format, and technical functionality.

The final version of the questionnaire was sent to all 39 psychotherapeutic training institutions (via SoSci Survey) in Austria.

The response rate was 87%, with 34 training institutions out of 39 in Austria responding to the questionnaire. The answering participants were mainly female (24 women, 9 men, 1 diverse person), and an average age of 57.

Thirty-one out of thirty-four (94%) responding TI use CS as a training element, carrying them out during training.

All responding TI consider conducting CS during training to be very important or important (100%).

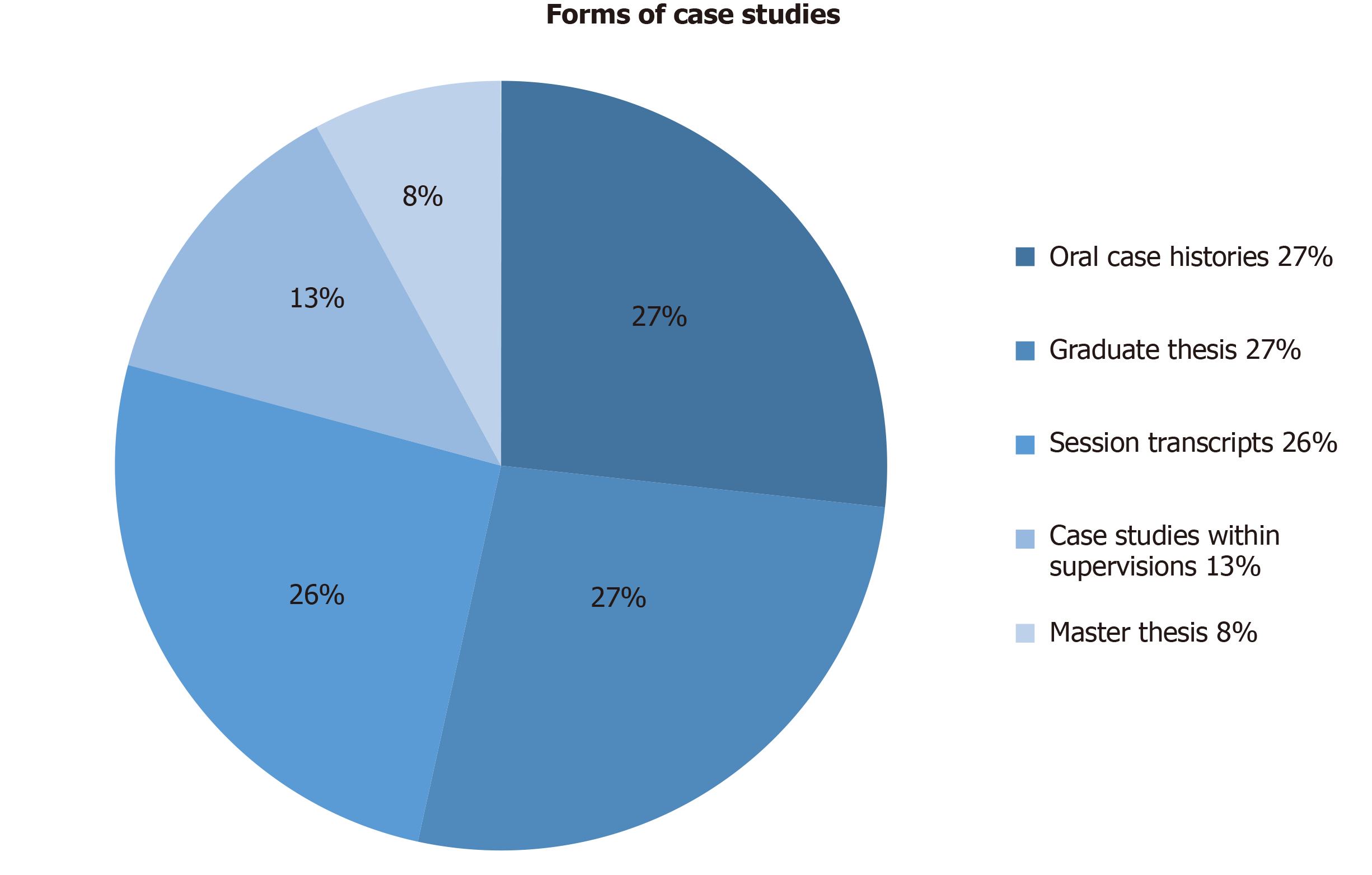

The number of CS written by training candidates during the training period varied between 0 and 30: Forms of case studies (Figure 2).

Forms of case studies: Case studies, (1) Mainly single case studies (42% “always”, 48.5% “frequently”); (2) Describe mainly one single patient (64.5%); and (3) Created mainly by one individual (77.5% “always”, 22.5% “frequently”). Teamwork or working in group occurred “rarely” or “never” (100%).

The study shows that there are different interpretations and therefore different ways of using the term case study. Training institutions use the term case study in diverse contexts: Oral case histories, session transcripts or detailed written studies, etc. Only 8% of the papers referred to as case studies in this broad understanding of the term are written within the framework of master theses.

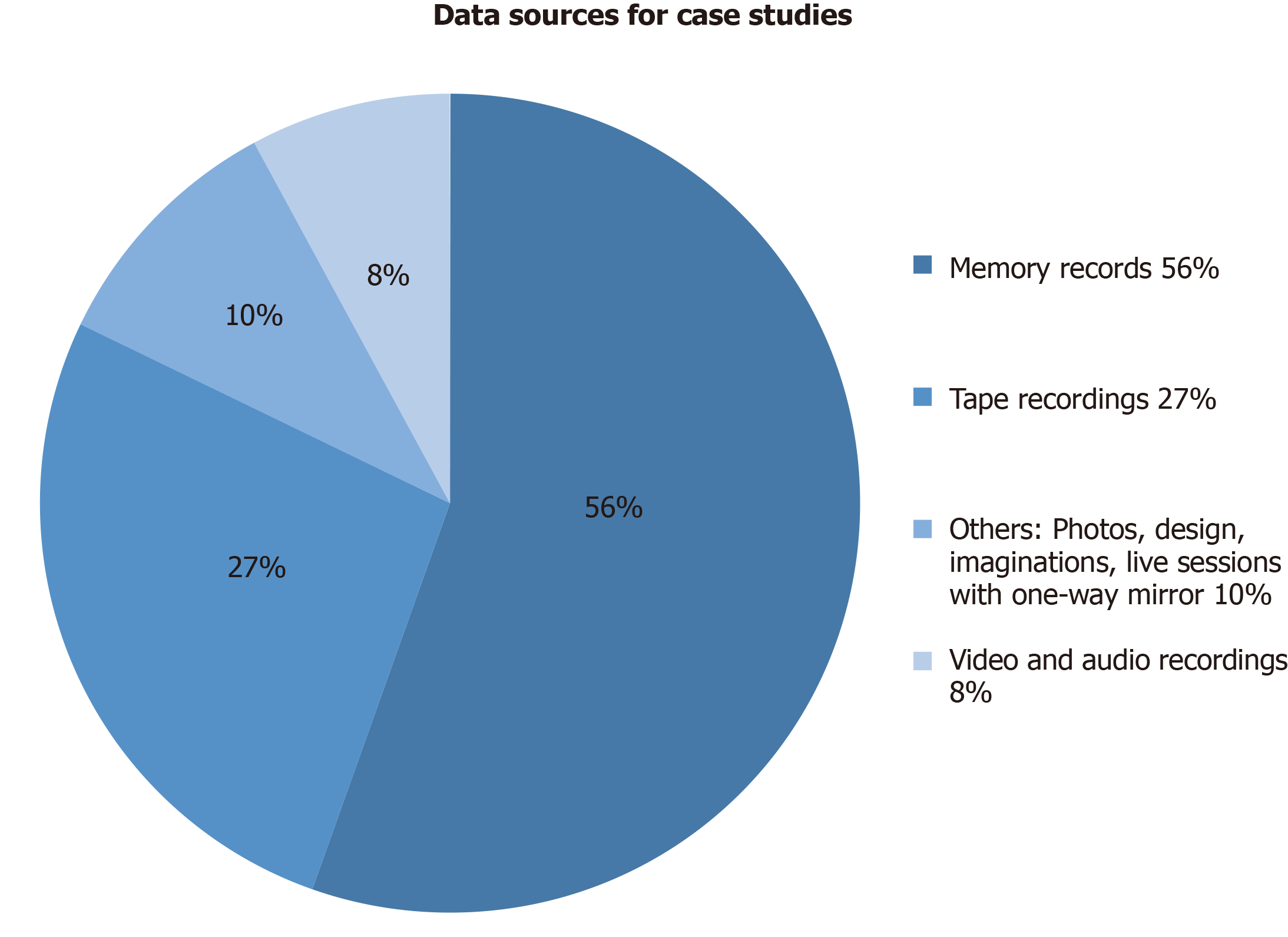

Their sources of material are mainly recalled written reports from memory (56%) and tape recordings (27%): Data sources for case studies in training (Figure 3).

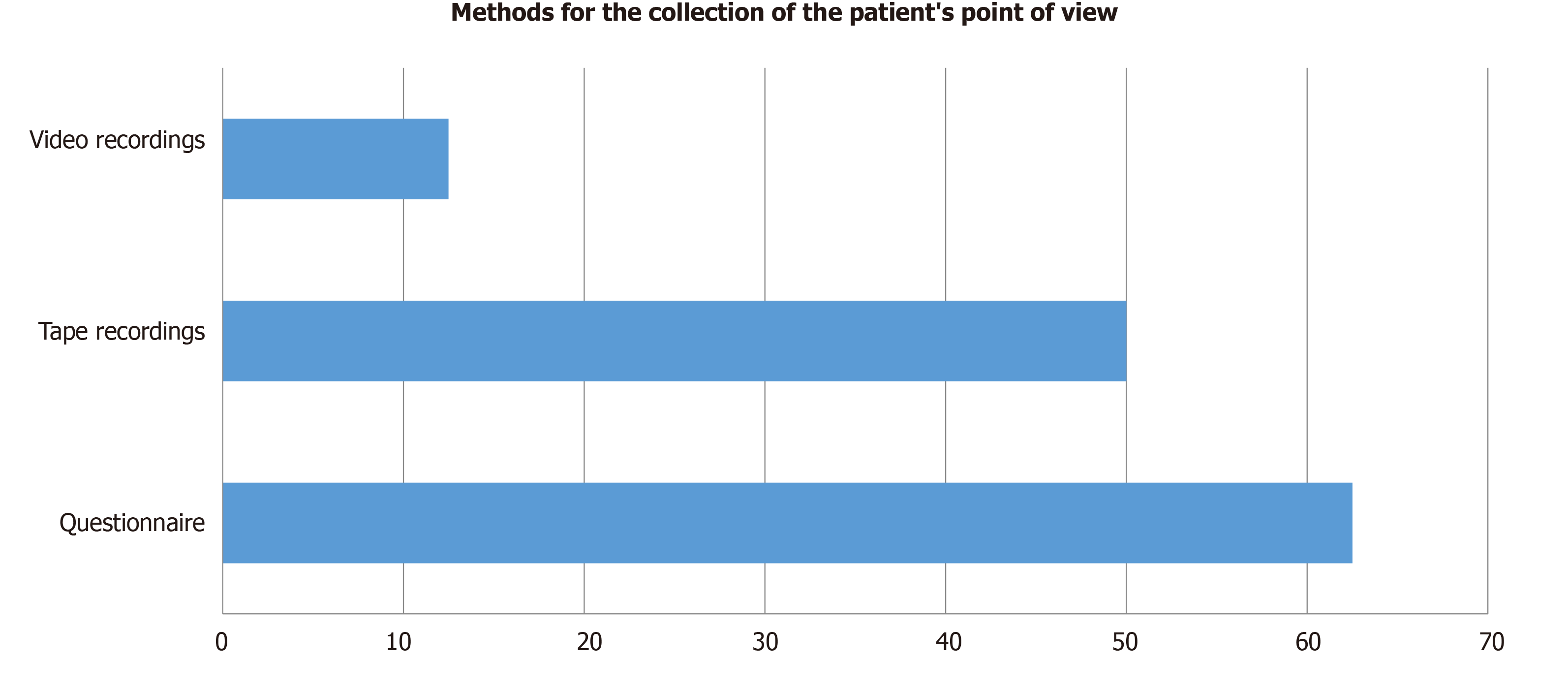

Inclusion of patient’s viewpoint in case studies: 69% of TI reported that the patients’ viewpoint is not gathered in CS; 31% affirmed the inclusion of patients (with interviews or questionnaires).

The means utilized in patient involvement are: Questionnaire (62.5%), evaluation of tape recordings of patients (50%), and evaluation of video recordings of patients (12.5%, are equivalent to 1 TI).

Including the documents created by the clients (e.g., drawings) was mentioned as an additional method. Including patient’s view (Figure 4), and methods of data collection (Figure 5).

| Case studies serve | Purposes of case studies | Percent (rounded), % |

| As a record of | The legitimization of becoming a psychotherapist | 97 |

| The implementation of practical skills in individuals’ psychotherapeutic work | 97 | |

| Theoretical knowledge of one’s own psychotherapeutic method | 81 | |

| If the intervention technique applied is appropriate | 84 | |

| To learn | To reflect upon one’s own work | 97 |

| To observe and consider meta levels (body language, vocal pitch, transmission, etc.) | 87.5 | |

| The language and the methodology of writing down and describing a therapeutic process | 84.5 | |

| Examples of best practice | 37.5 | |

| To gain knowledge | About diagnoses | 68.5 |

| About the behavior of the patients | 72 | |

| As part of a larger study within one`s own psychotherapeutic method | 19 | |

| For quality assurance | Through process evaluation | 81 |

| As means of communication | Between training candidate and supervisor | 75 |

| With the health insurance companies | 10 |

In 47% of the institutions that responded to the questionnaire, the CS always serves to demonstrate the theory learned, 47% state sometimes, and 3% state that the CS never serves to present the theory learned.

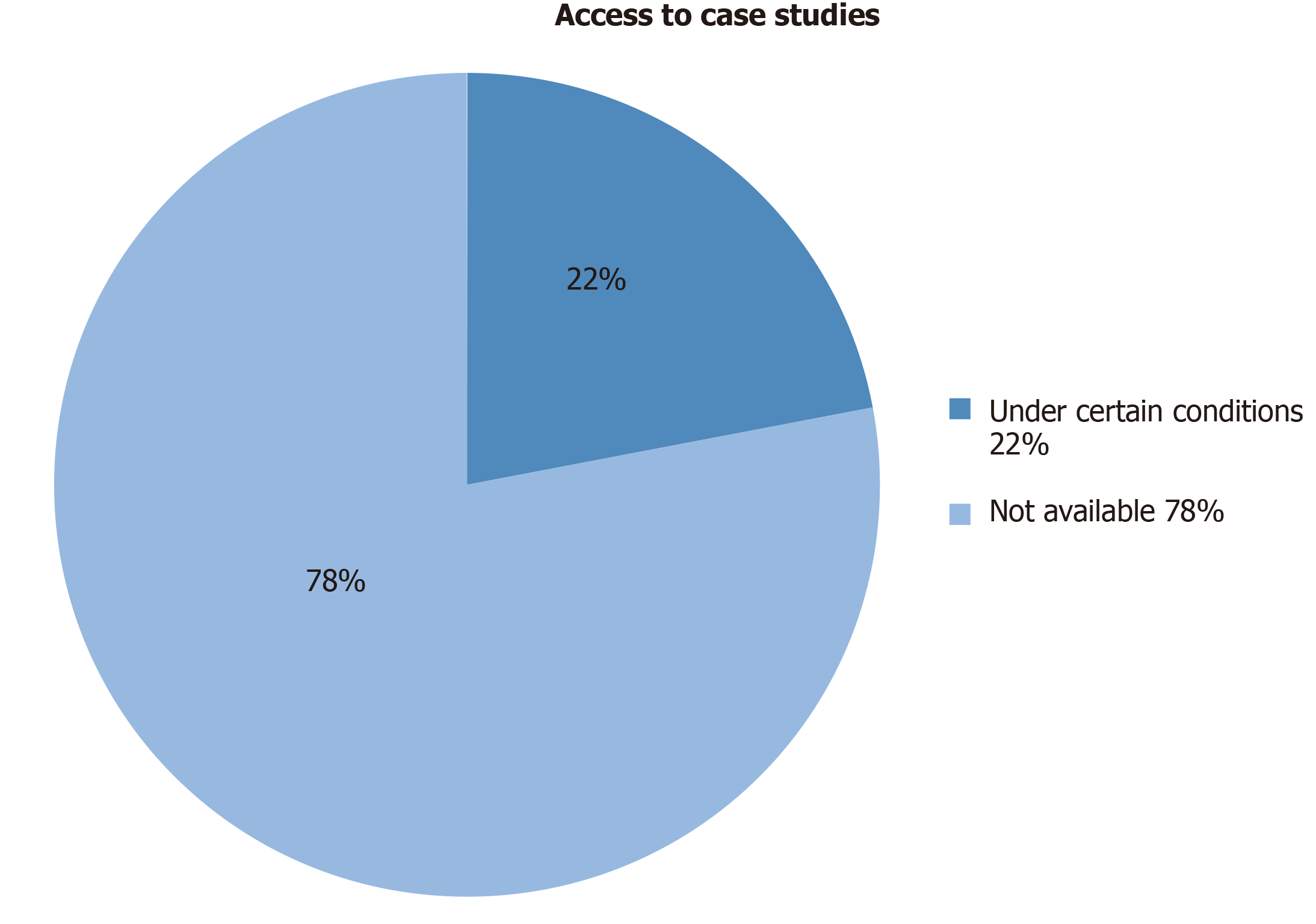

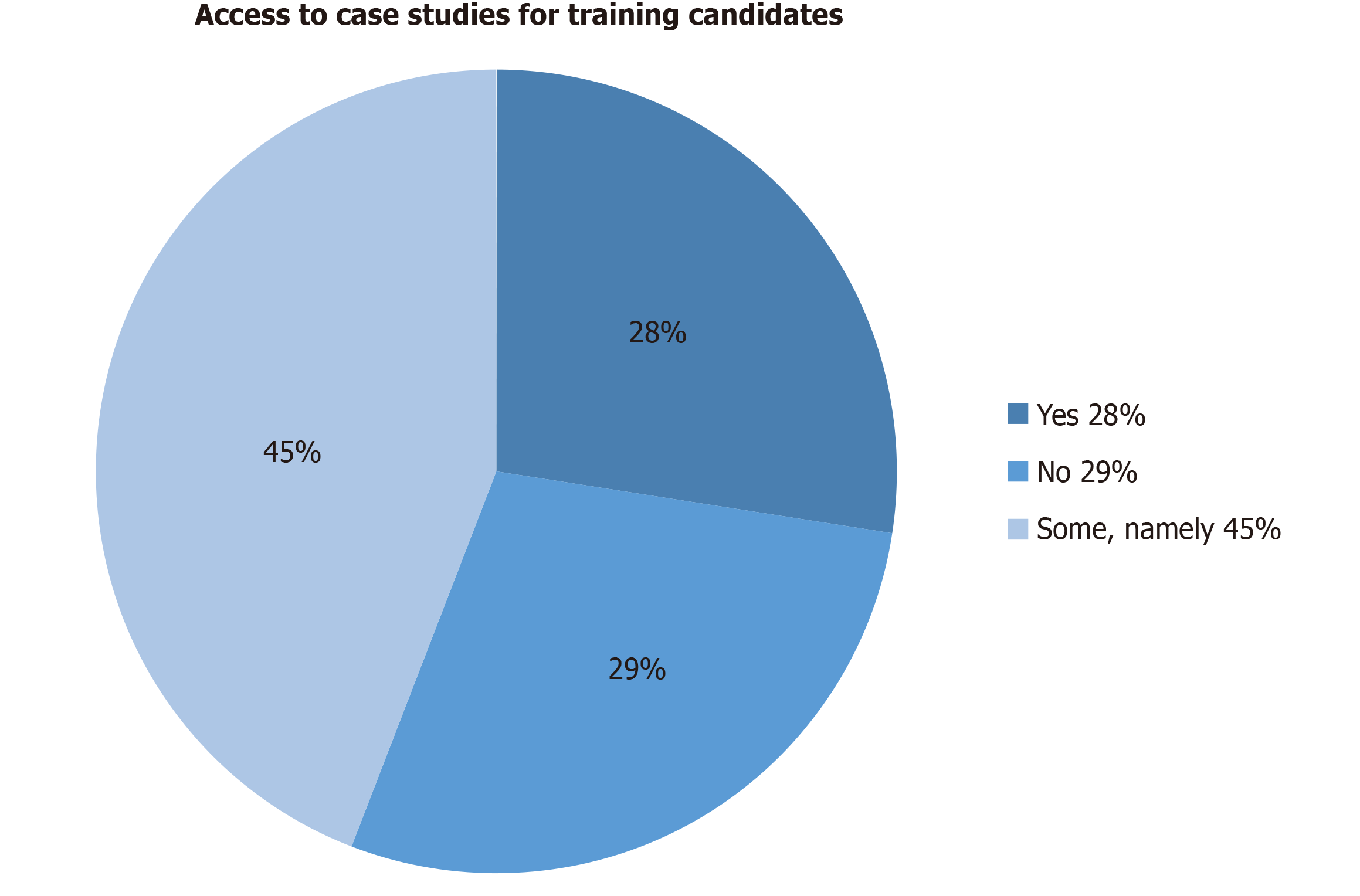

Access to case studies: For 77.5% of the psychotherapist(s) in training (PIT), the case studies are not publicly available.

The remaining 22.5% are accessible under certain conditions: (1) When the individual’s author approval is given; (2) As part of master theses (anonymization is emphasized); and (3) Or in the context of scientific publications.

In 26% of TI the case studies are accessible to the PIT, in 29% of TI the psychotherapists in training have no access to the case studies, and 45% offer access under certain conditions: (1) Best practice example; (2) Handset, copying ban, confidentiality obligation; (3) For lectures; (4) If the CS is a research project or a publication; and (5) If the CS is a master thesis. Access to case studies (Figure 6), access to case studies for training candidates (Figure 7).

Publication of case studies: The vast majority of CS is not published (84%). The remaining 16% are published by the training institutes. 6.5% of the institutions encourage the PIT to publish their case studies on internet platforms.

Criteria for conducting case studies: 90.5% of the different psychotherapeutic disciplines provide criteria on how to conduct a case study; 74% of these are in written form.

In the questionnaire, the query about criteria was open-ended. All answers were brief and general, stating that criteria mainly refer to: (1) Diagnostics; (2) Description of the progress; (3) Presentation of interventions; (4) Realizing interpretation and/or transference (regarding psychoanalytic disciplines); (5) Theoretical classification (rationale of interventions); and (6) Knowledge of the relevant literature.

In responding to the question of criteria pertaining to how to conduct CS, the study participants provided little information. There were overlaps with the answers to the question concerning how to evaluate CS. The criteria for evaluation were described in detail more than the criteria relevant to conducting a CS. 84% of TI consider creating case studies to be scientific work; 13% reject this notion.

Guidelines/standard procedures for conducting case studies: The majority of TI (76%) provide guidelines or standard procedures for conducting a CS.

The majority (73.5%) of these guidelines are established by the TI itself, 31.5% were derived from best-practice examples, and 16% were deduced from psychotherapeutic literature. McLeod and DGVT Fort- und Weiterbildung were named as sources of psychotherapy literature for guidelines. Two thirds of the TI refused to make their guidelines available for this study (68.5%).

Concerns about conducting case studies: 88.5% of TI has no concerns about CS. 11.5% expressed concerns about ethics and privacy.

Evaluation and assessment of case studies: The majority of written case studies is evaluated and rated (80.5%). CS is rated equally by supervisors and/or teaching therapists (68%) and by their own assessment boards (24%). 4% of CS is evaluated by training colleagues.

Criteria for rating case studies: The following criteria were mentioned when asked about the assessment criteria for CS (open-ended question): (1) Ability to reflect (most frequently mentioned), especially with regards to (a) the therapeutic relationship (in psychodynamic methods especially, aligned with transference/countertransference); (b) the therapeutic process (progress); and (c) interventions; (2) Diagnostics (most frequently mentioned separately from “reflection”); (3) References to theory (especially related to ones` own psychotherapeutic method); (4) Knowledge of relevant literature; (5) Formal criteria: Accuracy, plausibility, clarity; and (6) Scientific working (a) correct citation; and (b) use of relevant literature. Also, frequently mentioned nouns included: Originality, alienation of data.

Therapist allegiance bias: Table 2 gives an overview of given answers towards the question of “How do CS in psychotherapy training counter therapist allegiance bias?”

| Dealing with bias | Percent (rounded), % |

| By reflection | 50 |

| By methods | 23 |

| By methods and reflection | 11.5 |

| Not at all | 15.5 |

The term reflection in Table 2 is used in a general manner and refers to discussion among the training therapists as well as self-reflection (e.g., reflection of the countertransference), and it encompasses discussions during supervision as well as use of current research literature.

The term method is also not specified by the TI. In the table, several terms such as “social science evaluation methods”, “phenomenological approach”, “imaginations”, “cross-method approach”, “transposition of methodical terms from one psychotherapy school to another” were summarized as methods.

In the statements, therapist allegiance bias notwithstanding, two opposing approaches could be found from “not (yet) at all” and “that is not part of the training” or “cannot be avoided”: One group showed openness as to dealing with this bias, the other did not.

Our hypothesis that there is no clear usage of the term case study and that there are glaring differences among training institutions is confirmed by the study.

The different ways to obtain professional qualification in Austria and the large number of psychotherapeutic methods (23) is reflected in the various methods of handling CS: There is a wide range of numbers of (written) CS (0-30), also in terms of the quality of CS required (some having no specifications, others with detailed guidelines). Manuals on how to conduct CS are available, particularly in the context of master theses.

More than two thirds of the CS exclusively covers the perspective of the trainees, and about one third include the patients’ perspective (by means of interviews or questionnaires). The question of how to deal with therapy allegiance bias was answered by most of the TI quite vaguely. Three quarters of the TI handle therapist allegiance bias through reflection (not precisely defined) and application of (scientific) methods.

A quarter of the TI do not take therapist allegiance bias into account at all.

Since psychotherapeutic work represents a highly complex process embedded within numerous practical factors, it seems obligatory to define the methodological approach and thus refine the term case study for psychotherapy itself (interdisciplinarily).

Case presentations can both be written and oral (e.g., case presentations in supervision, transcripts of sessions, oral case presentations in training groups). They serve, above all, as a platform to exchange the knowledge taught and learned.

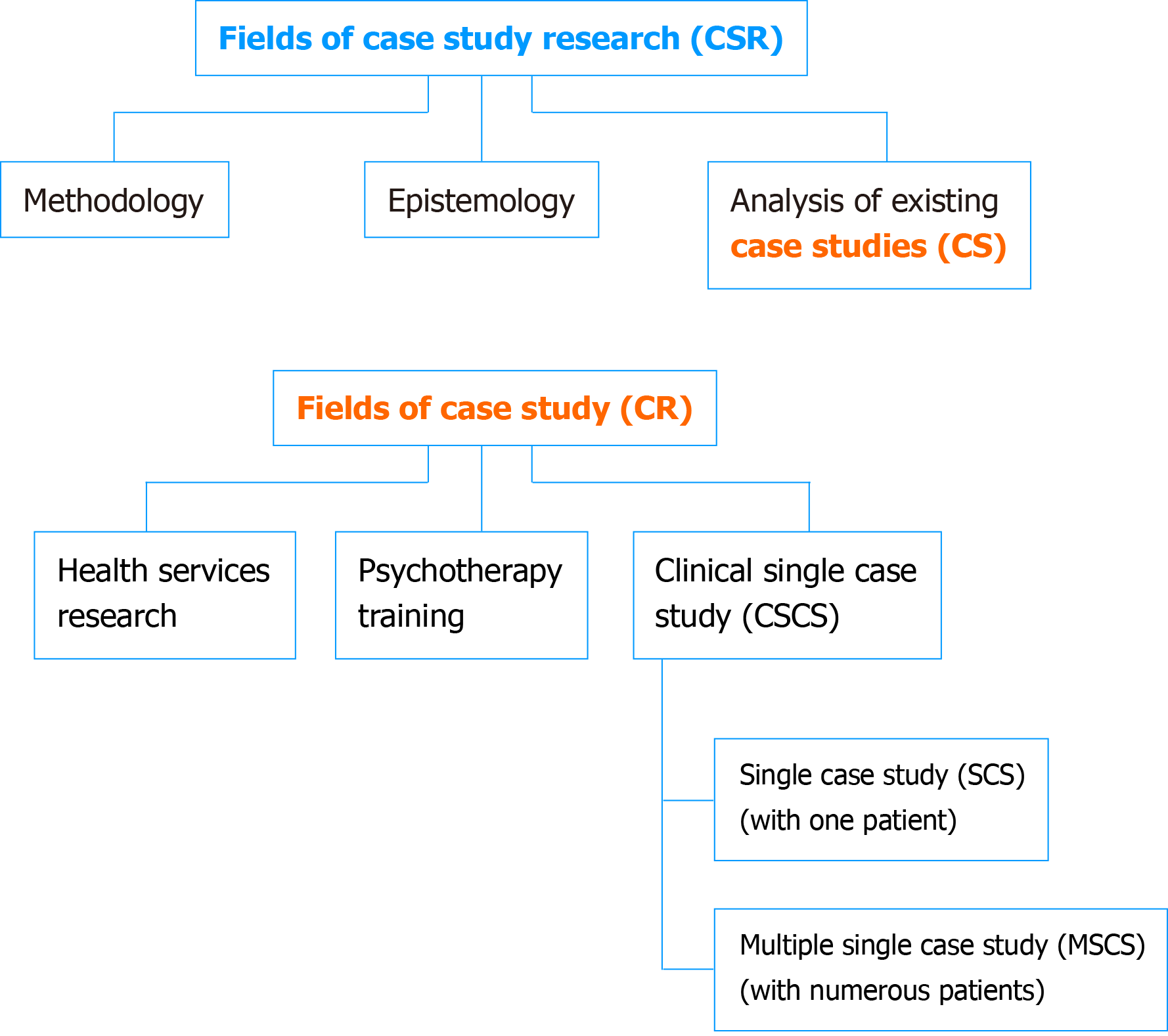

Case study: The written case study in psychotherapy usually refers to a single case study (analyzing the history of one single patient). Also, most of the participants of this study interpreted the term in that way. Widdowson[18] proposes a methodology by which a case study might also consist of a single episode within a session, a single session, a particular phase or “chunk” of therapy, or an overview of the entire therapy. That represents a widespread restriction in using the term case study in psychotherapy. This interpretation of case study is juxtaposed with the expanded concept of case study, which is used inter alia in social research. In the expanded concept, the “case” can not only be the patient to be examined, but also a question of training research (e.g., what is the role of self-awareness for the development of therapeutic key competencies?) Questions about the role of the therapist may also lead to a hypothesis-generating study (e.g., a study on “Role of research in Gestalt Therapy in Austria” can be designed as a qualitative case study with quantitative elements.)

The single case study and the multiple-single case study can be considered as a subgroup of case studies that are of particular importance within training.

A case study in psychotherapy serves to empirically investigate the processes involved in psychotherapy. The questions can be both hypothesis-testing and hypothesis-generating. The “object” of the investigation (“case”) can include – analogously to CS in sociology – questions concerning processes, efficacy, as well as queries concerning psychotherapy training, or it can also be the analysis of the treatment of a single patient (individual clinical examination).

The clinical single case study represents a special section of single case study research and is frequently used in training psychotherapists. So far, there is no consensus about guidelines (in contrast with medicine, i.e. CORE) pertaining to clinical case studies in psychotherapy.

The research methods relative to conducting single clinical case studies differ depending on the query and on the study design (i.e. combinations of different research methods and triangulation of data[3,4,19]). Differences between case study and case study research (Figure 8).

The written CS describing the unfolding of the process – in retrospect – can lead to a wide range of professional insights for trainees in terms of combining practice and theory, as well as enhance competence in conceptualizing treatments. Moreover, these findings may lead to more confidence in face-to-face interactions with clients.

Still, there are several areas in written case studies used in training that lack evidence-based research (for example, with respect to assessment criteria being referenced for determining whether and/or how a student’s competence improved).

Regarding the outcome of treatment, social desirability as a source of bias has to be taken into account (i.e. the students want to show that the therapy was successful, thus demonstrating/proving his/her competence).

The assessment of written case studies in psychotherapy training could function as an additional source of bias if the assessing trainers do not take into account their own school allegiance.

The “blind spots” of the students operate as another potential bias: what is not seen by the prospective psychotherapist himself/herself is not dealt with in supervision or final written thesis because it cannot be reported. The written clinical single case study using written records exclusively as data sources, collected by the trainees themselves (currently 56% in this study), is therefore questionable as a tool to test competencies in training.

The single clinical case study in psychotherapy as a written method can convert implicit knowledge into explicit, verbalizable knowledge – at least to a certain extent. During the psychotherapeutic treatment session, the skillful practitioners will apply their implicit knowledge again and again while interacting. No one thus far has been able to establish a psychotherapeutic treatment session that is “right” or “optimal”. The effects of unpredictable actions, reactions, and interactions relate to several aspects (topics/contents, resonance/transferences, state of mind on that day, physical condition etc.), which concern both participants, client/patient and psychotherapist. This potentiates the possible consequences ad infinitum. Nevertheless, there are treatment sessions that definitely stabilize, soothe, or cure mental disorders (and probably some which do not). Evidently, psychotherapeutic work requires a great deal of implicit knowledge intertwined with empirical knowledge.

By examining empirical clinical work doing CS, we are collecting parts of this implicit knowledge to be able to investigate it in detail and therefore get information about how we can best transfer this expertise to novice students (training research), gain further knowledge about how and why something is efficient or not (research of outcome), verify/invalidate existing theories and models of explanations (hypothesis-testing research), and last but not least, generate new assumptions (hypothesis-generating research) when examining short- and long-term psychotherapy processes in practice.

Critically, Castonguay et al. note that psychotherapy research would have led to a kind of empirical imperialism, “that (…) in many programs of research in which individuals who see very few clients per week decide what should be studied and how it should be investigated, to understand and facilitate the process of change”[6].

The unique existence in Austria of so many different psychotherapeutic methods and the various possibilities offered to obtain professional qualification could deliver insights into these processes of changes, as lecturers teaching in postgraduate training institutes are often working regularly and in parallel in private practice, with a considerable number of weekly patients.

Falkenström et al[8] recommends that future studies should rigorously consider the school background. Baxter and Jack[16] suggest increasing the validity and credibility of studies in psychotherapy by actively involving clients/patients in the process of evaluation.

Most single case studies in psychotherapy are written by the therapist himself/herself, which exacerbates the bias. Most of the CS conducted in training do not gather or consider the client’s position. Those studies tend to have very low validity.

Taking into account the points of view of the clients enhances the validity of CS (to demonstrate treatment success), while implementing this in practice would be fairly easy (e.g., mixed method designs).

The data collected for the CS can help to further diminish possible therapist allegiance bias. Tape recordings of the sessions allow the training therapists to see potential blind spots of their students. It is video recording that is most revealing in terms of how therapists in training and patients/clients interact, and they are the method of choice to capture what is not reported by the novice psychotherapists, because these aspects are by definition not reportable. Video recordings seem therefore to be an important tool to develop and enhance competencies and professional skills as a psychotherapist (yet currently, only 4 out of 34 responding TI in Austria use videos as a data source for CS).

Peer examinations are another possibility to broaden the perspectives of the individual PIT. The group setting provides the opportunity to implement double coding as well as double categorizations for text analyses (e.g., qualitative content analysis as per Mayring) or standardized coding tools (e.g., psychoanalytical dream coding as per Moser and Zeppelin). Finally, the blinding techniques mentioned above are additional methods available to counterbalance researcher allegiance bias.

Comparison of criteria and methods of assessment of the written studies used by the different training institutes could bring new insights that would minimize school allegiance bias of both the trainees and of the assessing trainers, as well as social desirability bias.

Due to ethical reasons as well as the need to assure anonymity (especially that of the trainees), the evaluation might be biased with respect to the impact from and on the training candidates. For instance, because of anonymity, it is not clear whether 20 or 200 training candidates were reached in the survey and affected. 14 large institutions train 73% of all prospective psychotherapists, while the other 26 small institutions train 27% (there were a total of 3789 psychotherapists in training).

Another source of distortion results from the uneven clustering of the study participants. That is to say, if one compares the number of students by cluster (see Figure 1) against the participants of the study (Figure 2), it is clear that psychodynamic schools are overrepresented in comparison with the real number of training candidates per psychotherapeutic cluster. Comparison of training candidates and study participants by cluster (Figure 9).

This distortion might have been resolved by abolishing anonymity and by including the sizes of the institutes (or the number of training candidates per institute). This was omitted to avoid another bias, social desirability, i.e. to positively present the achievements of one’s own institute.

Although the survey was conducted anonymously, the confounding factor of social desirability might still have an impact, as currently and in the past 7 years the Federal Ministry in Austria requests the TI to conduct more research[20].

This observational study holds a high external validity because the participants joined the query voluntarily and the response rate of the population was high (87%).

Alternatively, another research approach to answering the questions about CS in Austrian psychotherapy training might be a systematic review of a specified number of CS from all TIs. This methodological approach could serve to verify or supplement the results of the current study.

This exploratory study shows that there is currently no consensus among TI in Austria with respect to methodology for CS. What access is appropriate for the CS produced during training? Is there a need for several different approaches to support students in choosing their methods? Is it necessary to have several models to account for different epistemological backgrounds of the different methods of psychotherapy?

Or is it possible – analogous to the common effectiveness factors[21] – to establish general guidelines on how to conduct CS in Austrian training institutions (e.g., on the basis of Fishman[22], McLeod[23], Flyvbjerg[24])? Benefits would include: More orientation for the students; an increase in scientific level (through interdisciplinary formats based on current scientific standards); and synergistic effects (in the sense of evaluability) for research.

Epistemological differences among clusters and methods may be an obstacle in establishing a common basis for case studies in psychotherapy, or they might be a source of enrichment, if such diversity brings about a strong consensus which hopefully corresponds more to the variety of psychotherapeutic processes than emphasis on one-dimensional themes.

It is often stated that a large number of CS serve as marketing instruments to confirm the effectiveness of one’s own psychotherapeutic method, and that CS also serve to confirm preconceived notions of the researcher. All of this criticism can only be refuted if one consciously deals with therapist allegiance bias. This applies to all areas of psychotherapy research, to major international studies, as well as to CS during training. The training therapists likely play a key role, as they are the ones who model and teach how to deal with distorting factors.

Single-case, exploratory studies are essential for generating hypotheses and fill research gaps.

A common, broadly accepted and reliable structure for case studies is lacking in practice-oriented psychotherapy research.

The survey explores the current situation of the usage of case assignments.

According to grounded theory, inductive and deductive approaches were conducted (focus groups, survey, qualitative content analysis).

Data reports the usage of case assignments for training issues, rarely for research issues. Therapists’ and researchers’ bias is stated.

In order to establish valid and objective structures for personalized psychotherapy research, guidance to establish and to attune case-study research is necessary. Existing guidelines have to be implemented with more concerted efforts.

A deeper understanding of cases in order to detect new research questions, new clinical approaches can be very useful in the field of practice oriented clinical research. Mixed methods research designs including also patient-public involvement, in-depth interviews, interpretative analyses are helpful, a commonly attuned structure and guidance is necessary.

Part of this paper was presented at the 49th International Annual Meeting – SPR, June 2018, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Final results were presented at the 5th Joint United Kingdom and European SPR Chapters Conference, September 2019, Krakow, Poland. The authors thank Guoruey Wong, an English native speaker, for English proofreading prior to submission.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Austria

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Rovas L S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Rosian K, Winkler R. Psychotherapie – Begriffe, Wirkfaktoren und ein deutschsprachiger Ländervergleich zu gesetzlichen Regelungen. LBI-HTA Projektbericht Wien: Ludwig Boltzmann Institut für Health Technology Assessment 2017: 93. Available from: https://www.psyonline.at/contents/14836/psychotherapie-begriffe-wirkfaktoren-und-ein-deutschsprachiger-laendervergleich-zu-gesetzlichen-regelungen retrieved 15.6.2020. |

| 2. | Sagerschnig S, Tanios A. Ausbildungsstatistik 2016. Psychotherapie, Klinische Psychologie, Gesundheitspsychologie. Wien: Gesundheit Österreich GmbH, 2016. Available from: https://jasmin.goeg.at/53/1/Ausbildungsstatistik%202016_Psychotherapie%2C%20Klinische%20Psychologie%2C%20Gesundheitspsychologie.pdf retrieved 29.4.2020. |

| 3. | Riess G. „Was bisher geschah …“ Prinzipien und Strategien zur Förderung der Psychotherapieforschung in Österreich. Psychotherapie Forum. 2016;21:35-43. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Löffler-Stastka H. Quantitative und qualitative Methoden in der Psychotherapieforschung incl. Beurteilungsmöglichkeiten von Studien - Schwerpunkt qualitative Methoden. In: Riess G, Gesundheit Österreich GmbH. Psychotherapieforschung. Wissenschaftliche Beratung und Vernetzung. Tagungs-band zum Workshop; 2012. Available from: https://jasmin.goeg.at/386/1/Psychotherapieforschung.%20Wissenschaftliche%20Beratung%20und%20Vernetzung%207_11.pdf retrieved 29.04.2020. |

| 5. | Castonguay LG, Nelson DL, Boutselis MA, Chiswick NR, Damer DD, Hemmelstein NA, Jackson JS, Morford M, Ragusea SA, Roper JG, Spayd C, Weiszer T, Borkovec TD. Psychotherapists, researchers, or both? A qualitative analysis of psychotherapists' experiences in a practice research network. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2010;47:345-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Castonguay L, Barkham M, Lutz W, McAleavey A. Practice-Oriented Research: Approaches and Applications. In: Lambert M. Bergin and Garfieldâs Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change (6th Edition). Hoboken: Wiley, 2013: 85-133. Available from: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Bergin+and+Garfield%27s+Handbook+of+Psychotherapy+and+Behavior+Change%2C+6th+Edition-p-9781118038208 retrieved 15.6. 2020. |

| 7. | Munder T, Gerger H, Trelle S, Barth J. Testing the allegiance bias hypothesis: a meta-analysis. Psychother Res. 2011;21:670-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Falkenström F, Markowitz JC, Jonker H, Philips B, Holmqvist R. Can psychotherapists function as their own controls? Meta-analysis of the crossed therapist design in comparative psychotherapy trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:482-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dragioti E, Dimoliatis I, Evangelou E. Disclosure of researcher allegiance in meta-analyses and randomised controlled trials of psychotherapy: a systematic appraisal. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Anderson T, Crowley ME, Himawan L, Holmberg JK, Uhlin BD. Therapist facilitative interpersonal skills and training status: A randomized clinical trial on alliance and outcome. Psychother Res. 2016;26:511-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lieb K, von der Osten-Sacken J, Stoffers-Winterling J, Reiss N, Barth J. Conflicts of interest and spin in reviews of psychological therapies: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wampold BE, Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Yulish NE, Frost ND, Pace BT, Goldberg SB, Miller SD, Baardseth TP, Laska KM, Hilsenroth MJ. In pursuit of truth: A critical examination of meta-analyses of cognitive behavior therapy. Psychother Res. 2017;27:14-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McLeod J. An Introduction to Research in Counseling and Psychotherapy. London: Sage Publications Ltd, 2013. Available from: https://www.bookdepository.com/Introduction-Research-Counselling-Psychotherapy-John-McLeod/9781446201411 retrieved 15.6. 2020. |

| 14. | George A, Bennett A. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2005. Available from: https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/case-studies-and-theory-development-social-sciences retrieved 15.6. 2020. |

| 15. | Starman AB. The Case Study as a type of qualitative research. Journal of Contemporary Educational Studies. 2013;1:28-43 Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-case-study-as-a-type-of-qualitative-research-Starman/1cc27a1b28050194da8bef5b2ab807386baa286e retrieved 15.6.2020. |

| 16. | Baxter PE, Jack SM. Qualitative Case Study Methodology: Study Design and Implementation for Novice Researchers. Qual Rep. 2008;13 Suppl 4:S544-S559 Available from: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol13/iss4/2 retrieved 29.04.2020. |

| 17. | Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Blinding in randomised trials: hiding who got what. Lancet. 2002;359:696-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 581] [Cited by in RCA: 595] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Widdowson M. Case Study Research Methodology. International Journal of Transactional Analysis Research. 2011;2 Suppl 1:S25-34. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Schigl B. Von der Idee zur Eingrenzung der Forschungsfrage über die Thesenbildung bis zum Design. In: Riess G, Gesundheit Österreich GmbH, Psychotherapieforschung. Wissenschaftliche Beratung und Vernetzung. Tagungsband zum Workshop 2012. Wien: Gesundheit Österreich GmbH, 2013: 43-50. Available from: https://jasmin.goeg.at/386/1/Psychotherapieforschung.%20Wissenschaftliche%20Beratung%20und%20Vernetzung%207_11.pdf retrieved 29.04.2020. |

| 20. | Riess G, Kern, Breyer E, Hochgerner M, Korunka C, Laireiter AR, Loeffler-Stastka H, Mehta G, Schigl B, Wieser MA, Yilmaz. Praxisorientierte Psychotherapie forschung. Leitfaden zur Förderung von Wissenschaft und Forschung in der psychotherapeutischen Ausbildung. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Lambert M. The efficacy and effectiveness of psychotherapy. In: Lambert M. Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change (6th Edition). Hoboken: Wiley, 2013: 169-218. Available from: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Bergin+and+Garfield%27s+Handbook+of+Psychotherapy+and+Behavior+Change%2C+6th+Edition-p-9781118038208 retrieved 15.6. 2020. |

| 22. | Fishman D. Editor's introduction to PCSP – from single case to database: a new method for enhancing psychotherapy practice. Pragmat Case Stud Psychother. 2005;1 Suppl 1:S1-50. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | McLeod J. Case Study Research in Counseling and Psychotherapy. Los Angeles: Sage, 2010. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Flyvbjerg B. Case Study. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage 4th ed, 2011; 301-316. Available from: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2278194 retrieved 15.6. 2020. |