Published online Jun 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i12.2662

Peer-review started: February 26, 2020

First decision: April 21, 2020

Revised: April 28, 2020

Accepted: May 21, 2020

Article in press: May 21, 2020

Published online: June 26, 2020

Processing time: 119 Days and 0.3 Hours

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) is a multicause pulmonary capillary hemorrhage or pulmonary vascular small vessel injury (mainly capillaries, including arteries and veins), causing pulmonary microcirculation blood to accumulate in the alveolar space. DAH is classified by the histological absence or presence of pulmonary capillaritis (PC) and is rarely reported in the literature.

This is a report of three girls aged 6-11 years with DAH and PC. Two patients had decreased hemoglobin and one had increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate. High-resolution computed tomography showed bilateral diffuse pulmonary infiltrate, and diagnosis of PC was confirmed by lung biopsy. Immunofluorescence test in one case showed granular IgG and a small amount of granular IgA deposit on the alveolar walls, and was negative in the other two cases, describing isolated pauci-immune PC. Treatment was with glucocorticoid alone or combination with immunosuppressants, and the symptoms resolved in all patients.

PC is classified as isolated and immune-mediated PC associated with systemic disease. It can be controlled in most children with glucocorticoid alone or combined with immunosuppressants.

Core tip: This is a report of three children with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and pulmonary capillaritis who presented with recurrent hemoptysis: One was antinuclear antibody-positive and two were antibody-negative. The condition can be controlled in patients using glucocorticoid alone or combination of immunosuppressant treatment.

- Citation: Xie J, Zhao YY, Liu J, Nong GM. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage with histopathologic manifestations of pulmonary capillaritis: Three case reports. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(12): 2662-2666

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i12/2662.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i12.2662

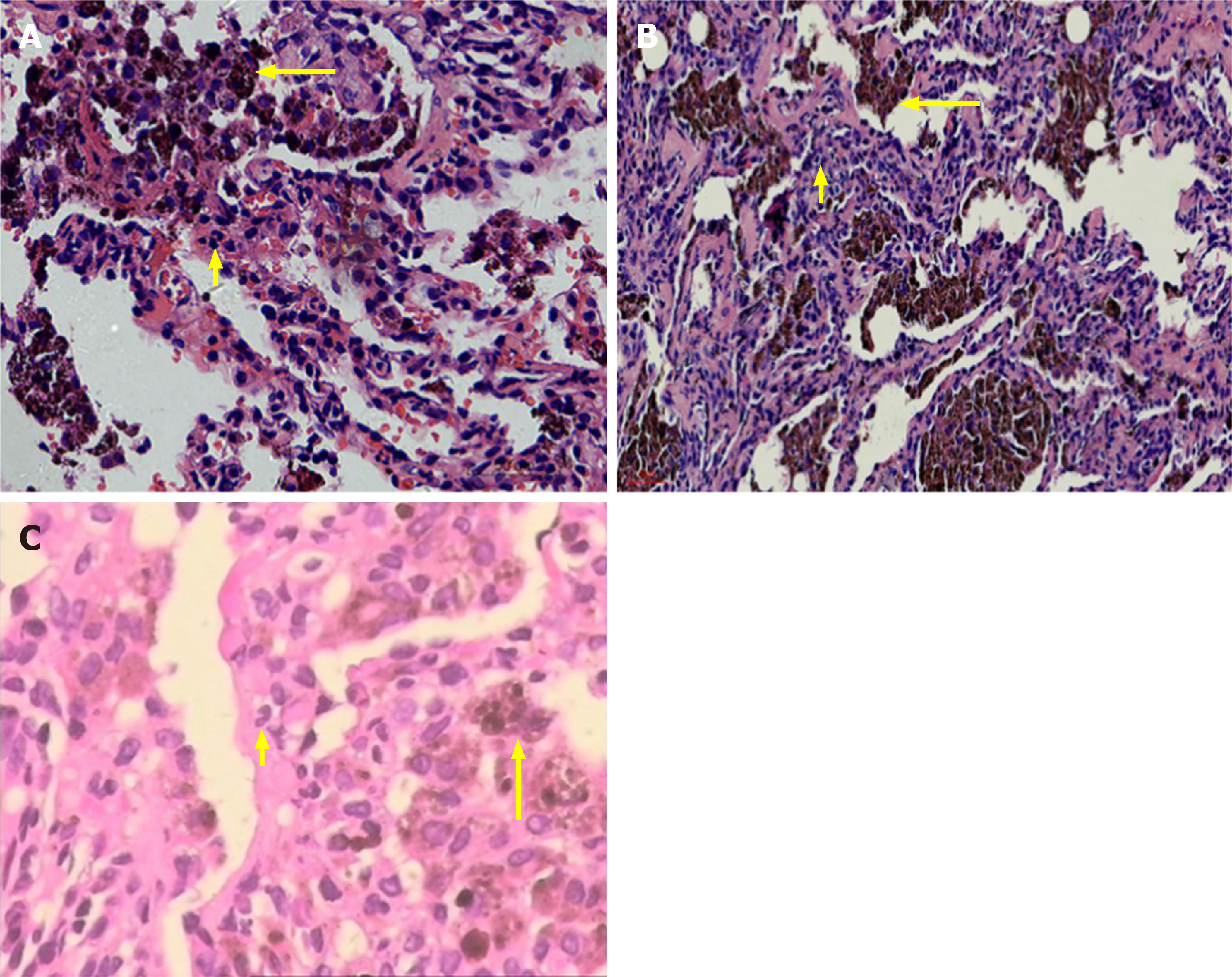

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) is a rare, and life-threatening disease in children. It is reported that DAH in children is associated with common causes such as oligoimmunity, immune complex deposition, and others (mainly due to medication)[1]. DAH is divided into DAH in the presence or absence of pulmonary capillaritis (PC), and DAH of cardiac origin[2]. PC is characterized by the presence of cough, shortness of breath, dyspnea, with or without hemoptysis[3], and iron deficiency anemia. Histopathology of PC is manifested as neutrophil aggregation or infiltration at the tight junction of alveolar interstitial and alveolar capillaries[4], as well as nuclear debris. Red blood cells and hemosiderin-laden macrophage cells (HLMs) exuded from capillaries are seen in the alveolar spaces and interstitium. In this report, we describe three patients with PC diagnosed by lung biopsy.

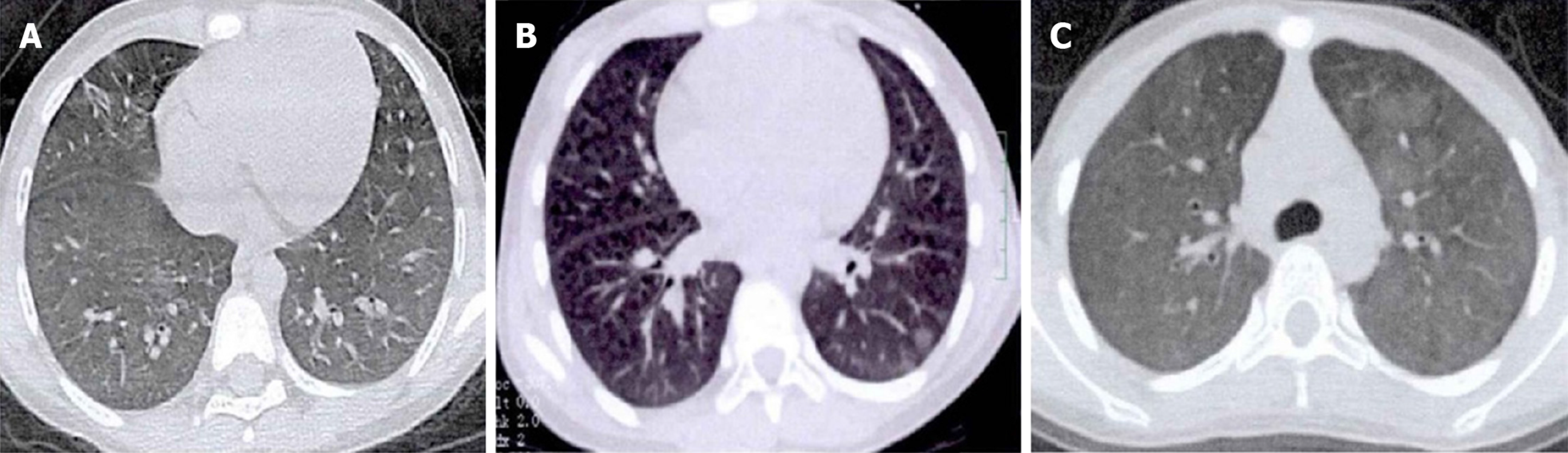

A girl aged 6 years and 3 mo presented with repeated pale skin and cough for > 2 years. She was allergic to chicken protein and milk and denied medical history and family genetic diseases. Hemoglobin was 109 g/L, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 48 mm/h, and urinalysis, renal function, coagulation function and serum ferritin were normal. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) (IgG) was positive, immunofluorescence revealed granular type (1: 320), and the other tests were negative. Chest high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) showed patchy density and ground-glass opacity in multiple lobes (Figure 1A). A right upper lung biopsy showed typical DAH and PC (Figure 2A).

A girl aged 11 years and 6 mo was admitted to hospital with a 3-year history of recurrent of cough and hemoptysis. She previously had episodes of hemoptysis for which she had received multiple treatments, including antibiotics and glucocorticoids. Laboratory examination revealed hemoglobin 75 g/L. Evaluation was normal for ESR, urinalysis, renal function, ANA, and anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody (GBM). Chest HRCT showed diffuse cystic lesions in bilateral lung fields (Figure 1B). There were no malignant cells in the bronchoalveolar lavage smear, and HLMs were visible. A diagnosis of PC was confirmed on right lung biopsy that showed spilled red blood cells and HLM aggregation, and a small amount of lymphocyte and neutrophil infiltration, typical of DAH and PC (Figure 2B).

A girl aged 11 years and 11 mo presented to our hospital with a history of recurrent pale skin and hemoptysis for > 1 year. The child had no significant past medical problems, and had no exposure to toxic chemicals, fumes, or other irritants. Auxiliary examination showed hemoglobin 79 g/L. She was admitted; evaluation included normal results for platelets; and ESR, urinalysis, renal function, coagulation function, ANA, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were within the normal range. Chest HRCT showed diffuse ground-glass opacity in the bilateral lung fields. Histopathology of the lung biopsy was typical of DAH, but the lesions were mainly in the chronic phase (fibrosis, lymphatic, and plasma cell infiltration) (Figure 2C).

Case 1 was positive for ANA (IgG) and immunofluorescence test revealed granular IgG, and a small amount of granular IgA deposit on the alveolar wall combined with minimal change glomerulonephritis, which suggested systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Cases 2 and 3 were diagnosed with isolated pauci-immune PC (IPPC), which was based on histopathological evidence of PC in the absence of clinical and serological evidence of an underlying systemic disorder.

The patient was given oral prednisone 10 mg/d (1.58 mg/kg/d) with subsequent gradual taper plan over 3 mo.

The child was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 54 mg q12 h (4 mg/kg/d) for 5 d, follow by oral prednisone at a dose of up to 30 mg/d (1 mg/kg/d), and this relieved her symptoms of cough, hemoptysis, and shortness of breath.

The patient was treated with prednisone 30 mg/d (1.2 mg/kg/d) for 4 mo, gradually reduced to 15 mg/d (5 mg every 2 mo) for 9 mo. This resulted in symptom improvement of the pulmonary hemorrhage.

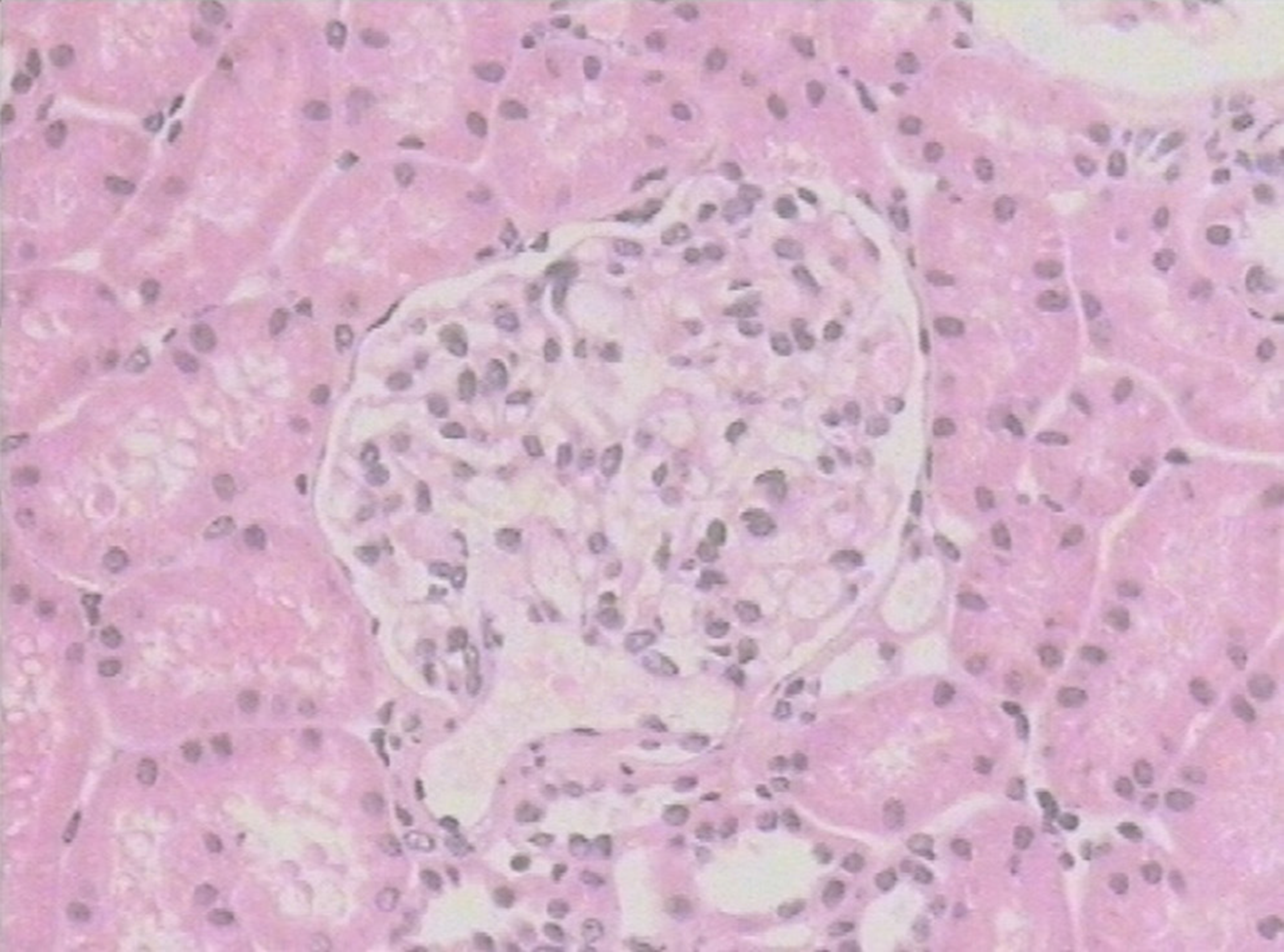

The patient attended regular outpatient review, and symptoms were improved. Hemoglobin was 128-147.8 g/L; ESR WAS 29 mm/h; chest HRCT showed that the lung lesions improved; and percutaneous kidney biopsy was performed and revealed minimal change glomerulonephritis (Figure 3). Oral prednisone was gradually reduced (5 mg every 2-3 mo), and 14 mo later, the prednisolone dose was tapered from 5 mg/d to a maintenance dose of 5 mg every other day. Follow-up has been completed for 2 years with no evidence of recurrence after discontinuation of prednisone.

Follow-up hemoglobin concentration fluctuated at 117.4-128.8 g/L; ESR was normal; chest HRCT showed partial absorption of inflammatory lesions, and the remaining lesions were similar to before. After oral administration of prednisone for 2 years, the dose was reduced to 5 mg/d. During that period, the patient was hospitalized twice for DAH, and the dose of prednisone was increased to 60 mg/d (1.5 mg/kg/d), and methotrexate was added at 12.5 mg once weekly. Four years after the initial diagnosis, the child remained on therapy and the symptoms had resolved, but she developed Cushing’s syndrome.

The patient had regular follow-up visits, and she had no cough or hemoptysis, no pale skin. Routine blood examination showed hemoglobin 112.6-140 g/L, and ESR, routine urinalysis and anti-GBM antibody were negative. Chest HRCT showed that the lung lesions were not aggravated compared with before. The patient has been stable and asymptomatic for 3 years.

PC is a histopathological type of DAH that is characterized by inflammatory cell infiltration and blood accumulation in the alveolar cavity[5,6]. Two of the present cases were diagnosed with IPPC, which was based on histopathological evidence of PC in the absence of clinical and serological evidence of an underlying systemic disorder[3]. In Case 1, ANA autoantibodies (IgG) were positive and immunofluorescence test revealed granular IgG, a small amount of granular IgA deposit on the alveolar wall, combined with minimal change glomerulonephritis, which suggested SLE[7,8]. Only 5% of SLE patients reportedly have DAH, but PC, IgG, and complement C3 immune complex deposits are observed microscopically in nearly 50% of cases[8]. There is no unified diagnostic standard for SLE with PC. The clinical symptoms of most PC patients are inconspicuous, and lung pathology is the gold standard for diagnosis.

Currently, glucocorticoids alone or combined with immunosuppressants to control inflammation and autoimmune response remain the standard treatment for most patients. It is reported that glucocorticoids (starting with intravenous methylprednisolone 2-4 mg/kg/d for 1-3 d, followed by oral prednisone 1-2 mg/kg/d; or starting with oral prednisone 1-2 mg/kg/d)[1] are effective, but fail in some cases. When glucocorticoids are ineffective, immunosuppressants are recommended, including oral methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, and azathioprine[9-11]. After addition of immunosuppressants, the condition in most cases can be controlled[9,10]. Rituximab and recombinant-activated human factor VIIa seem to be a new promising therapy[3,12].

PC is classified as isolated PC and immune-mediated PC associated with systemic disease. The condition can be controlled in most children using glucocorticoids alone or in combination with immunosuppressants.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): C

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abe Y S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Green RJ, Ruoss SJ, Kraft SA, Duncan SR, Berry GJ, Raffin TA. Pulmonary capillaritis and alveolar hemorrhage. Update on diagnosis and management. Chest. 1996;110:1305-1316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Afessa B, Tefferi A, Litzow MR, Krowka MJ, Wylam ME, Peters SG. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:641-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Thompson G, Specks U, Cartin-Ceba R. Isolated pauciimmune pulmonary capillaritis successfully treated with rituximab. Chest. 2015;147:e134-e136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vece TJ, Fan LL. Diagnosis and management of diffuse lung disease in children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2011;12:238-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Franks TJ, Koss MN. Pulmonary capillaritis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2000;6:430-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lee AS, Specks U. Pulmonary capillaritis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;25:547-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hannah JR, D'Cruz DP. Pulmonary Complications of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;40:227-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Barile-Fabris L, Hernández-Cabrera MF, Barragan-Garfias JA. Vasculitis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014;16:440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Flanagan F, Glackin L, Slattery DM. Successful treatment of idiopathic pulmonary capillaritis with intravenous cyclophosphamide. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013;48:303-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kupfer O, Ridall LA, Hoffman LM, Dishop MK, Soep JB, Wagener JS, Fan LL. Pulmonary capillaritis in monozygotic twin boys. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e1445-e1448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Stainer A, Rice A, Devaraj A, Barnett JL, Donovan J, Kokosi M, Nicholson AG, Cairns T, Wells AU, Renzoni EA. Diffuse alveolar haemorrhage associated with subsequent development of ANCA positivity and emphysema in three young adults. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19:185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Park JA, Kim BJ. Intrapulmonary recombinant factor VIIa for diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in children. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e216-e220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |