Published online Jun 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i12.2585

Peer-review started: March 26, 2020

First decision: April 29, 2020

Revised: May 27, 2020

Accepted: May 30, 2020

Article in press: May 30, 2020

Published online: June 26, 2020

Processing time: 88 Days and 4.8 Hours

Acute phosphate nephropathy (APN) is a disease that can occur when exposed to high doses of phosphate. The most common cause of APN is the use of oral sodium phosphate for bowel cleansing preparations. However, there are other less commonly known sources of phosphate that are equally important. To date, our literature search did not identify any report of excessive dietary phosphate as a cause of APN.

We report an unusual case of a 39-year-old diabetic male who presented with epigastric pain and oliguria. Work-up showed elevated serum creatinine, potassium, and calcium-phosphate product, and metabolic acidosis. The patient was admitted in the intensive care unit and received emergent renal replacement therapy. Kidney biopsy revealed tubular cell injury with transparent crystal casts positive for Von Kossa staining, which established the diagnosis of APN.

This case confirmed that APN may occur with other sources of phosphorus, highlighting the importance of good history taking and kidney biopsy in patients with predisposing factors for APN. Raising awareness on the possibility of APN and its timely recognition and management is imperative so that appropriate measures can be instituted to prevent or delay its progression to end stage renal disease.

Core tip: The classic case of acute phosphate nephropathy (APN) is caused by oral sodium phosphate for bowel cleansing preparations. In this case report, we present a rare incident of biopsy-proven APN caused by excessive dietary phosphate intake in a 39-year-old diabetic male. APN was diagnosed by history of increased dietary phosphorus intake, clinical presentation of acute kidney injury, laboratory findings of hyperphosphatemia and elevated calcium phosphate product, and kidney biopsy findings, which showed tubular crystals positive for Von Kossa stain. This case highlights the importance of good history taking and kidney biopsy for the diagnosis of APN.

- Citation: Medina-Liabres KRP, Kim BM, Kim S. Biopsy-proven acute phosphate nephropathy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(12): 2585-2589

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i12/2585.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i12.2585

Acute phosphate nephropathy (APN), previously called acute nephrocalcinosis, is a disease that can occur when exposed to high doses of phosphate. The classic cause of APN is the use of oral sodium phosphate for bowel cleansing preparations[1-3]. Jahan et al[4] reported a case of APN secondary to excessive intake of sodium phosphate tablets for hypophosphatemia. Aside from these, there are other less known sources of phosphate that are equally important. To date, our literature search did not identify any report of excessive dietary phosphate as a cause of APN. We report a case of a 39-year-old diabetic male who developed APN secondary to excessive dietary phosphate intake.

Epigastric pain for 5 d and acute onset oliguria.

A 39-year-old man with diabetes mellitus was admitted at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital for evaluation and management of acute kidney injury (AKI). He consulted at the emergency room due to epigastric pain that started five days prior and decreased urine volume noted on the day of the visit. There was no accompanying vomiting, diarrhea, or fever.

The patient has been on insulin for diabetes mellitus since 5 years ago and has a history of being hospitalized for chronic pancreatitis and alcoholic hepatitis one year ago. He had no previous surgeries. He denied use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, and herbal or dietary supplements.

The patient had recently travelled to Japan. He worked as a chef, and upon detailed history taking, the patient claimed his diet only consisted of tomato meatball pasta and carbonara for nine consecutive days prior to his hospitalization. Each serving of meatball pasta contained 100 g shredded mozzarella cheese (656 mg phosphorus/100 g) and 1 slice of cheddar cheese (936 mg phosphorus/100 g), while each serving of carbonara included 100 g mozzarella cheese and 125 g camembert cheese (347 mg phosphorus/100 g). Pasta also has 253 mg phosphorus for every 100 g. The amount of phosphorus he consumed is estimated to be more than twice the recommended intake for adult men.

Upon admission, vital signs were normal. Physical examination showed signs of volume overload.

Laboratory test results showed azotemia (serum creatinine 12.85 mg/dL and urea nitrogen 85 mg/dL) and elevated potassium (6.7 mmol/L), uric acid (9.0 mg/dL) and phosphorus (3.62 mmol/L) levels. Patient was hypocalcemic at 1.65 mmol/L (corrected calcium 1.79 mmol/L). Serum magnesium (0.66 mmol/L) was normal. Parathyroid hormone was within acceptable limits for chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients. He also presented with uncompensated metabolic acidosis (pH 7.147, bicarbonate 11.8 mmol/L). Patient’s latest serum creatinine before hospitalization was 1.68 mg/dL three months prior (estimated glomerular filtration rate 50.8 mL/min per 1.73 m2). Due to the rapid deterioration of renal function, further work-up was requested to establish other possible causes of AKI and/or CKD progression. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), fluorescent antinuclear antibody (FANA), and anti-streptolysin O (ASO) were negative. Patient had normal C3 and C4 levels (95 mg% and 26.30 mg%, respectively). Random urine protein/creatinine ratio was 1322.81 mg/g.

On ultrasound, the kidneys were normal-sized (right 12.1 cm and left 11.6 cm), with increased cortical echogenecity. No suspicious focal lesions or signs of urinary obstruction were noted.

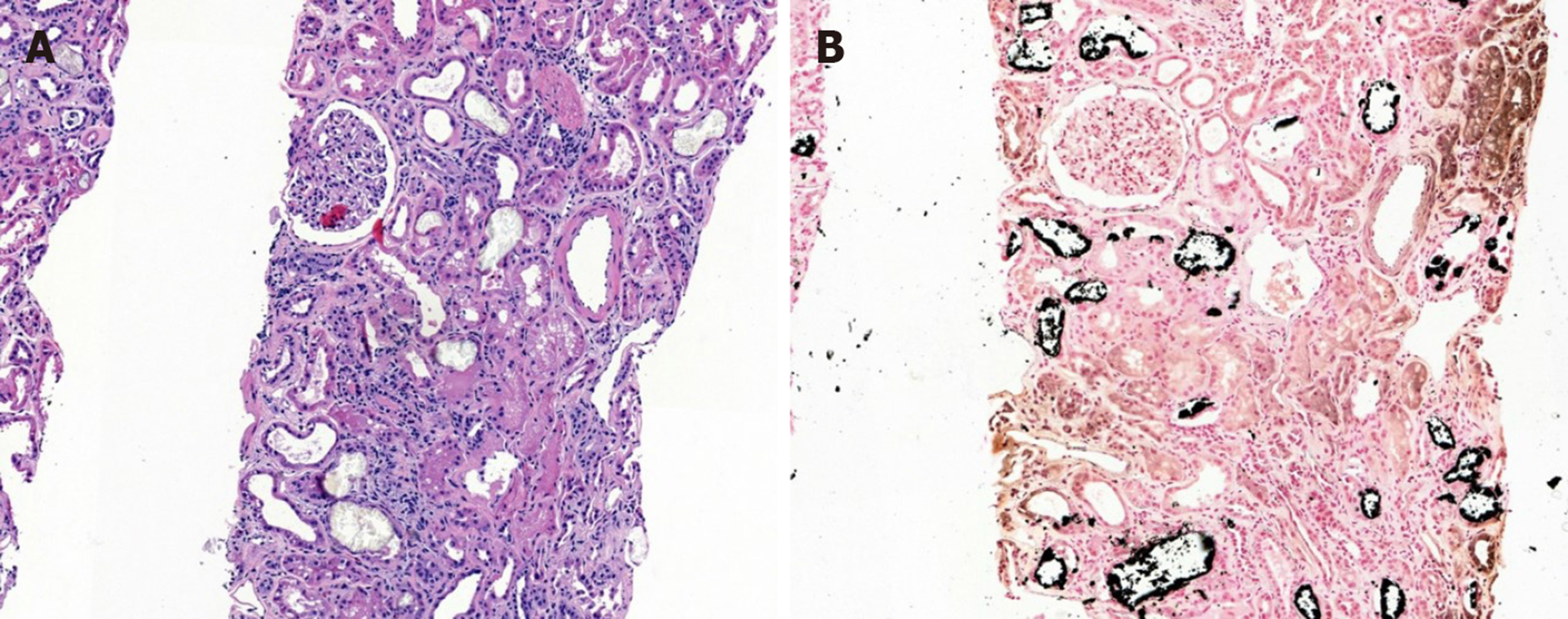

Kidney biopsy under ultrasound guidance was performed (Figure 1A) on the fourth hospital day. The kidney biopsy revealed normal to mildly enlarged glomeruli, but with partially shrinked glomerular tufts; marked focal atrophy, tubular cell injury with some transparent crystal casts. There was also marked focal interstitial fibrosis and focal infiltration of mononuclear cells and a few eosinophils. Fibrointimal thickening of blood vessels were also noted. The immunofluorescence was negative for immunoglobulins and complement factors. The tubular crystal materials were positive for von Kossa staining, which established the diagnosis of APN (Figure 1B).

The final diagnosis of the presented case is acute phosphate nephropathy.

An emergent acute renal replacement therapy (RRT) was performed on the first hospital day. During hospital stay, the patient was continuously assessed for improvement of symptoms and renal function recovery. Monitoring of renal function and electrolytes was likewise done (Table 1). Unfortunately, the patient did not recover renal function and was still hemodialysis-dependent during the 3-mo follow-up period. He was maintained on and compliant with thrice weekly 4-h hemodialysis sessions. He did not report of any adverse event. On follow-up, patient was asymptomatic, and had normal electrolyte levels. His latest serum creatinine was 7.84 mg/dL.

| Reference range | Day -90, baseline | Day 1, admission, and start of dialysis | Day 30 | Day 90, follow-up | |

| Urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 10-26 | 26 | 85 | 30 | 37 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.7-1.4 | 1.68 | 12.85 | 7.32 | 7.84 |

| Na (mmol/L) | 135-145 | - | 133 | 139 | 133 |

| K (mmol/L) | 3.5-5.5 | - | 6.7 | 5.8 | 5.3 |

| P (mg/dL) | 2.5-4.5 | 4.5 | 11.2 | 6.1 | 4.3 |

| Ca (mg/dL) | 8.8-10.5 | 9.3 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 9.4 |

| Mg (mg/dL) | 1.5-2.0 | - | 1.6 | - | - |

| Intact PTH (pg/mL) | 152-6841 | - | 205 | - | - |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.3-5.2 | 4.0 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 3.2 |

| pH | 7.38-7.469 | - | 7.147 | 7.365 | - |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 21-29 | - | 11.8 | 25.1 | - |

| Carbon dioxide (µmol/mol) | 24-31 | - | 14 | 28 | - |

We reported a unique case of APN diagnosed by history of increased dietary phosphorus intake, AKI, hyperphosphatemia, and kidney biopsy findings. Although the electrolyte imbalances present in the patient can be observed in renal failure of any etiology, the positive Von Kossa staining of the tubular crystals on histopathologic examination strengthens our diagnosis of APN.

APN is a tubulointerstitial nephropathy caused by the deposition of calcium phosphate crystals in the renal tubular epithelial cells, causing reactive oxygen damage, resulting in acute tubular injury, and subsequently tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis, with concomitant loss of kidney function. APN occurs in conditions that result in calcium or phosphate elevations in the blood or urine such as sarcoidosis, malignancy, medullary sponge kidney, and cystinosis.

Since phosphate concentration is regulated by oral phosphorus load and renal excretion, hyperphosphatemia can be attributed to excess phosphorus intake over a short period of time. The normal dietary intake of phosphorus among adults is 1.5 g but individuals with high dairy product intakes have diets with higher phosphorus density values. Other risk factors for the development of APN include female gender, advanced age, hypovolemia, ileus, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, liver disease, and renal impairment[5]. Tissue necrosis, a regular feature of liver failure, can lead to increased phosphate levels[6], especially in cases of failed spontaneous recovery from liver disease[7]. Liver dysfunction, such as in cases with portal hypertension, can also possibly increase the permeability of colonic mucosa to sodium phosphate[8]. The use of medications contributing to renal hypoperfusion such as renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, diuretics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs also predisposes to APN. Risk factors in this case were chronic hepatitis, diabetes mellitus and renal impairment.

The classic diagnostic criteria for APN include AKI, recent exposure to sodium phosphate, no evidence of hypercalcemia, renal biopsy findings of diffuse tubular injury with calcium phosphate deposits, and no other significant pattern of renal injury. However, the diagnosis of APN should also be considered in patients with other sources of phosphate, especially in patients with any of the risk factors. A kidney biopsy should be done in such patients for definitive diagnosis. The most important findings on biopsy are calcium phosphate deposits primarily in the tubular lumen and cytoplasm of tubular epithelial cells which stain intensely with Von Kossa stain[9], and tubular injury, with tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis.

Calcium-phosphate product (CPP) is generally regarded as the indicator of the risk of calcium phosphate precipitation in the kidney. Normal range is 21-45 mg2/dL2. CPP usually increases in cases of APN. Our patient’s CPP at the time of presentation was 80 mg2/dL2, strengthening the diagnosis of APN.

Patients who develop APN require rapid correction of electrolyte abnormalities and aggressive fluid resuscitation to promote renal phosphate excretion and prevent further calcium phosphate precipitation. However, aggressive fluid therapy should not be instituted in patients who are oliguric and with signs of fluid overload. In mild cases, conservative treatment such as phosphate-binding resins and calcium gluconate, is recommended. Hemodialysis is indicated in cases of severe hyperphosphatemia, symptomatic hypocalcemia, and severe renal failure with associated complications. Kidney injury in APN is usually reversible[10] however despite appropriate management, it may progress to chronic irreversible kidney disease. In a cohort of 21 patients by Markowitz et al[11], all patients developed chronic renal insufficiency and 19% eventually had end stage renal disease (ESRD) that required RRT.

Since most cases of APN are clinically silent or often present with non-specific symptoms, its true incidence cannot be determined. It is very likely that it is underrecognized as a cause of AKI and CKD. This case confirmed that APN may occur with excessive dietary phosphorus intake. Therefore, it is important to emphasize proper dietary restrictions to patients with predisposing factors such as renal insufficiency. APN should be considered in patients with acute onset renal failure of unknown cause or patients with pre-existing CKD who develop rapid worsening of kidney function for no apparent reason, especially in patients who have risk factors for APN. A kidney biopsy is essential to provide a definitive diagnosis.

Physicians should be cognizant of APN as most of the studies have revealed its long-term consequences such as irreversible, progressive renal injury. Timely recognition and management of APN is imperative so that appropriate measures can be instituted to prevent or delay its progression to ESRD.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: International Society of Nephrology, 202930.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Santos P S-Editor: Wang J L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Joo WC, Lee SW, Yang DH, Han JY, Kim MJ. A case of biopsy-proven chronic kidney disease on progression from acute phosphate nephropathy. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2012;31:124-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lochy S, Jacobs R, Honoré PM, De Waele E, Joannes-Boyau O, De Regt J, Van Gorp V, Spapen HD. Phosphate induced crystal acute kidney injury - an under-recognized cause of acute kidney injury potentially leading to chronic kidney disease: case report and review of the literature. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2013;6:61-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rocuts AK, Waikar SS, Alexander MP, Rennke HG, Singh AK. Acute phosphate nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2009;75:987-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jahan S, Lea-Henry T, Brown M, Karpe K. An Unusual Case of Acute Phosphate Nephropathy. Kidney Int Rep. 2019;4:1023-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Markowitz GS, Perazella MA. Acute phosphate nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2009;76:1027-1034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schmidt LE, Dalhoff K. Serum phosphate is an early predictor of outcome in severe acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Hepatology. 2002;36:659-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Baquerizo A, Anselmo D, Shackleton C, Chen TW, Cao C, Weaver M, Gornbein J, Geevarghese S, Nissen N, Farmer D, Demetriou A, Busuttil RW. Phosphorus ans an early predictive factor in patients with acute liver failure. Transplantation. 2003;75:2007-2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nir-Paz R, Cohen R, Haviv YS. Acute hyperphosphatemia caused by sodium phosphate enema in a patient with liver dysfunction and chronic renal failure. Ren Fail. 1999;21:541-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pálmadóttir VK, Gudmundsson H, Hardarson S, Arnadóttir M, Magnússon T, Andrésdóttir MB. Incidence and outcome of acute phosphate nephropathy in Iceland. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gonlusen G, Akgun H, Ertan A, Olivero J, Truong LD. Renal failure and nephrocalcinosis associated with oral sodium phosphate bowel cleansing: clinical patterns and renal biopsy findings. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:101-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Markowitz GS, Stokes MB, Radhakrishnan J, D'Agati VD. Acute phosphate nephropathy following oral sodium phosphate bowel purgative: an underrecognized cause of chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3389-3396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl. 2009;S1-S130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 1076] [Article Influence: 67.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |