Published online Jan 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i1.188

Peer-review started: September 2, 2019

First decision: November 13, 2019

Revised: November 28, 2019

Accepted: December 13, 2019

Article in press: December 13, 2019

Published online: January 6, 2020

Processing time: 126 Days and 11.5 Hours

A cystic lesion arising from the myometrium of the uterus, termed as cystic adenomyosis, has chocolate-like, thick viscous contents and contains various amounts of endometrial stroma below the glandular epithelium. It is an extremely rare type of adenomyosis.

Herein, we report an unusual case of a giant cystic mass in the pelvic cavity after uterine myomectomy. The patient complained of abnormal uterine bleeding and severe dysmenorrhea. After a levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) was inserted, her symptoms were greatly alleviated. However, the LNG-IUD was detected in the cystic cavity during the follow-up. For fear of the intrauterine device migrating into and damaging the surrounding viscera, surgical treatment was proposed. Therefore, laparoscopic resection of the lesion and removal of the LNG-IUD were performed and cystic adenomyosis with an LNG-IUD out of the uterine cavity was diagnosed.

We believe that myomectomy breaking through the endometrial cavity may have been a predisposing factor for the development of cystic adenomyosis in this case.

Core tip: Myomectomy breaking through the endometrial cavity may be a predisposing factor for the development of adenomyosis. A Mirena may provide effective therapeutic action for any pelvic endometrial deposit in different ways. In terms of management, laparoscopic uterine-sparing intervention may be a preferable choice for exophytic cystic adenomyosis.

- Citation: Zhou Y, Chen ZY, Zhang XM. Giant exophytic cystic adenomyosis with a levonorgestrel containing intrauterine device out of the uterine cavity after uterine myomectomy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(1): 188-193

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i1/188.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i1.188

Adenomyosis is a benign proliferative disease characterized by the contiguous spread of ectopic endometrial glands and stroma deep within the myometrium. A large cystic lesion, termed as a cystic adenomyosis, is an extremely rare form of adenomyosis with extensive secretory changes and haemorrhage that develops a cystic cavity more than 1 cm in diameter[1,2]. Cystic adenomyosis filled with chocolate-coloured blood always causes severe dysmenorrhea with a marginal response to drug therapy and surgical treatment is always recommended[3]. We present an unusual case of a giant exophytic cystic adenomyosis with a levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) out of the uterine cavity after uterine myomectomy.

A 45-year-old married woman (gravida 1, para 1) presented with abnormal uterine bleeding for 6 years after myomectomy and progressive dysmenorrhea for 2 years.

The patient previously underwent laparoscopic myomectomy at our hospital 6 years ago. In her first menses after surgery, the menstrual period lasted approximately 12 d, which was longer than her previous period of 7 d. The patient’s menstrual volume and pattern in the previous 7 d were the same as those before the operation, and then mild bleeding continued for approximately 5 d. The menstrual cycle showed no obvious change when compared to that before myomectomy. There had been no abdominal pain or uncomfortable symptoms since the surgery was completed. Two years previously, the patient complained of dysmenorrhea. The pain was recurrent in nature, associated with menstruation and exacerbated monthly, enough to incapacitate her routine activities. Thereafter, she experienced progressively worsening dysmenorrhea, refractory to any medication.

At a consultation in another hospital six months earlier, the B-mode ultrasound findings showed a cystic mass of approximately 9 cm in diameter located at the posterior uterine isthmus, and an LNG-IUD was inserted into the “uterine cavity”. Since the IUD insertion, her dysmenorrhea completely disappeared, and amenorrhea commenced. Three months before the referral, the IUD was outside of the uterine cavity and a giant cystic echogenic mass was detected by B-mode ultrasound at our outpatient department.

In 2011, the patient underwent laparoscopic myomectomy at our hospital because of a fibroid placed in the posterior uterine isthmus. The cavity of the fibrosis mass broke through the endometrial layer during the operation.

A large cystic mass located in the posterior aspect of the uterus.

The routine blood test (June 28, 2017) showed a white blood cell count of 7.3 × 109/L, neutrophil percentage of 63%, red blood cell count of 3.6 × 1012/L, haemoglobin concentration of 138 g/L, and platelet count of 192 × 109/L. The carbohydrate antigen 125 level was 8.0 IU/L, and the C-reactive protein level was 1.3 µg/mL.

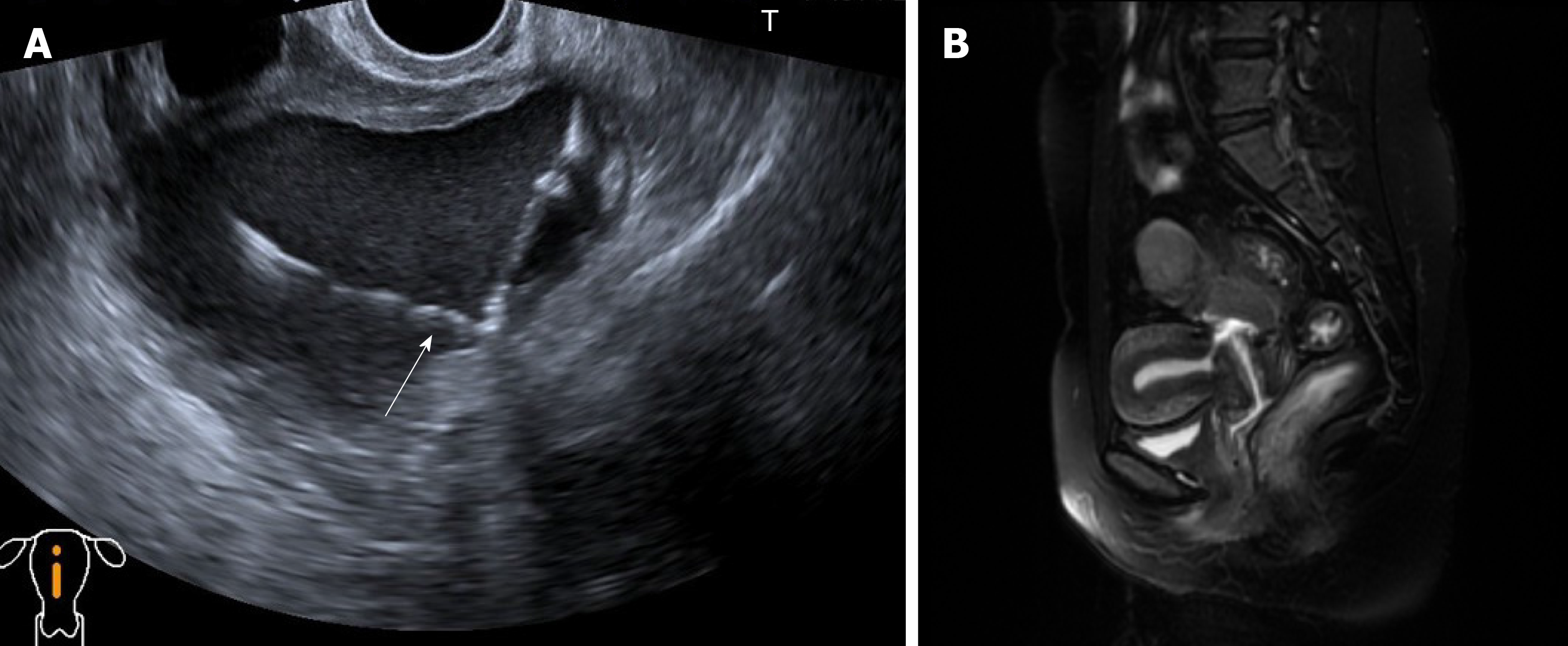

At a consultation in the hospital, the B-mode ultrasound findings (Figure 1A) showed an endometrial cystic mass containing an IUD. Since the operation, her dysmenorrhea completely disappeared, and amenorrhea commenced. In the preoperative evaluation, a large cystic lesion with endometrial-like signal in the pelvic cavity that communicated with the cervical canal was observed on magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 1B). Based on the magnetic resonance imaging, the presumptive diagnosis of an LNG-IUD contained within the pelvic endometrial cyst was proposed. Based on the imaging data and her history, the patient was clinically diagnosed with an endometriosis cystic mass located at the posterior uterine isthmus after myomectomy, with an LNG-IUD out of the uterine cavity.

The histopathology of the specimen confirmed the diagnosis of cystic adenomyosis. The final diagnosis was an exophytic cystic adenomyosis located at the posterior uterine isthmus after myomectomy, with an LNG-IUD out of the uterine cavity.

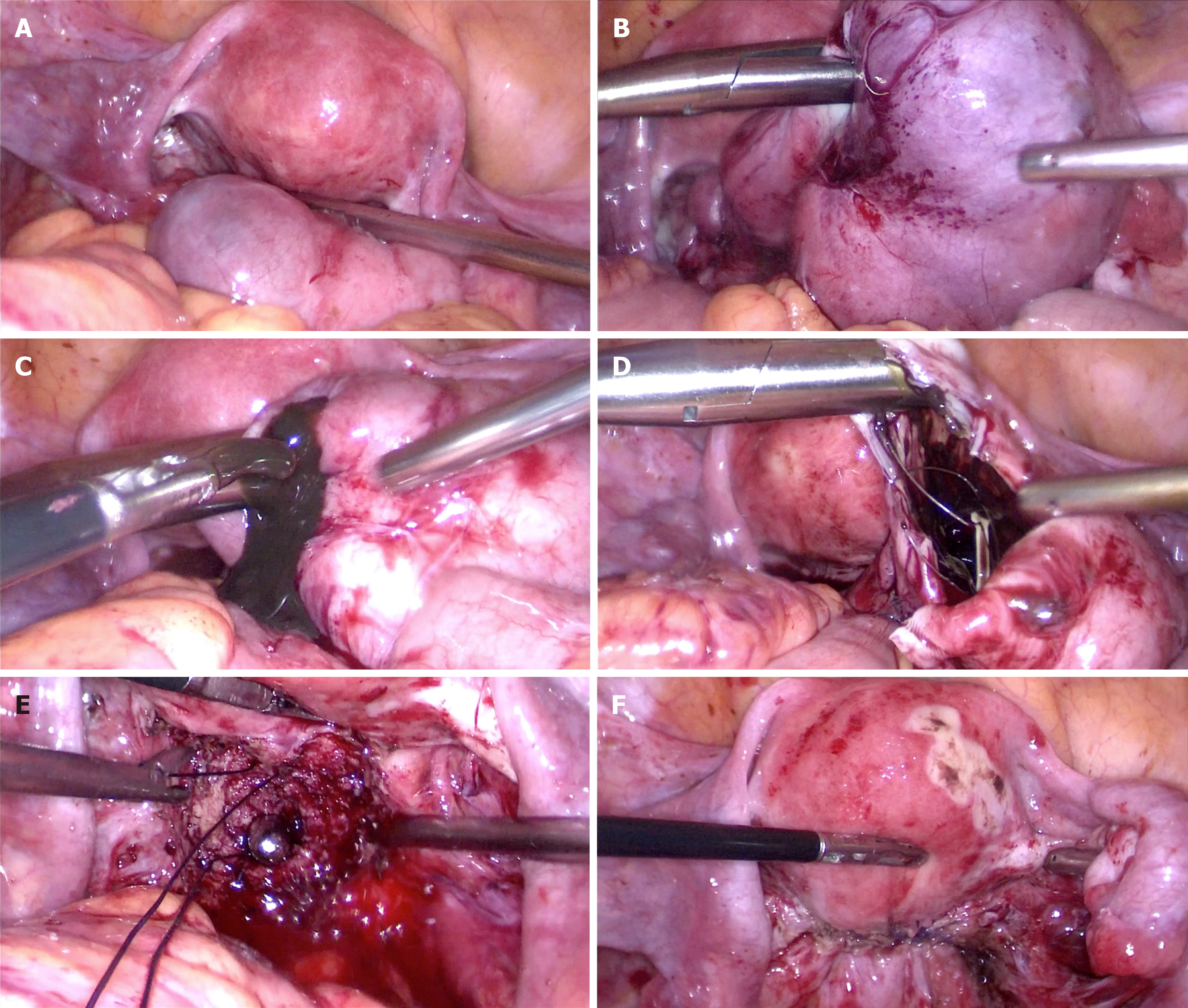

Because of fear that the IUD out of the uterine cavity would probably migrate into and damage the surrounding viscera, the patient was hospitalized for surgery. Laparoscopic excision of the mass was performed for the patient (Figure 2). The giant exophytic cystic mass and the LNG-IUD were removed during the operation.

The patient has been relieved from her symptoms of dysmenorrhea and abnormal uterine bleeding, starting from the first menstrual period after surgery to date. Table 1 shows the specific information of the patient before and after treatment.

| Time | Information |

| June 2011 | Laparoscopic myomectomy |

| July 2011 | The menstrual period lasted approximately 12 d |

| July 2015 | Dysmenorrhea occurred and worsened progressively |

| March 2017 | B-mode ultrasound findings showed an endometrial cystic mass at the posterior uterine isthmus, and a levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine device was inserted into the “uterine cavity” |

| June 2017 | A large cystic lesion in the pelvic cavity was observed by magnetic resonance imaging. The giant exophytic cystic mass and levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine device was removed via laparoscopic surgery |

| August 2017 | She has been relieved from symptoms of dysmenorrhea and abnormal uterine bleeding |

There exist a number of hypotheses regarding the pathogenesis of adenomyosis, and one hypothesis recognized by most people is the endometrial injury invagination theory[4]. The peristalsis and contraction of the uterus originate from the endometrial myometrial interface called the junctional zone. When trauma such as caesarean delivery, myomectomy, or curettage occurs at the junctional zone[5], a mechanism of tissue injury and repair will be activated, which results in increased local levels of E2[6]. Local hyperestrogenism is thought to lead to enhanced proliferation of endometrial cells and increased peristalsis of the junctional zone; hyperperistalsis allows “invasion” of the endometrium into the myometrium from the opening of the junctional zone, and the proliferated endometrium stimulates local uterine smooth muscle hypertrophy[7]. Moreover, excessive peristalsis will further damage the junctional zone, and then, the tissue injury and repair mechanism is re-activated again. This process forms a vicious circle that eventually leads to the development of adenomyosis[8]. When there are extensive endometrial secretory changes and haemorrhages in the endometrium that invades the myometrium, a cystic adenomyosis will develop[2].

As the classification is based on cyst location in the uterine wall, cystic adenomyosis is subdivided into five subtypes[9]: Subtype A1 includes the submucous or intramural cystic adenomyosis; subtype A2 includes cases of cystic polypoid lesions; subtype B1 includes subserous cystic adenomyosis; subtype B2 includes cases with exophytic growth; and subtype C comprises uterine-like masses within the uterus.

Here, we report a huge cystic adenomyosis that was suspected to be closely related to a prior uterine myomectomy history, which is supported by the following evidence. First, our patient began to experience abnormal uterine bleeding right after she underwent myomectomy as a result of the accumulated blood slowly outflowing from the cyst through the fistula that communicated with the cervical canal. Second, the cystic lesion was located at the site of the previous surgical wound, and the endometrial layer was broken through during myomectomy, inevitably causing damage to the junctional zone. Third, the patient suffered from progressively refractory dysmenorrhea in the past two years as the cyst gradually increased in size, which could be attributed to the collected intra-cystic secretions and periodic monthly bleeding that accumulated in the cyst. For these reasons, we believed that a prior uterine myomectomy could be the main predisposing factor for the transitional endometrium violating the myometrium, which is involved in the pathogenesis and development of cystic adenomyosis.

Interestingly, in this case, the LNG-IUD was actually inserted in the adenomyosis cyst instead of the uterine cavity, but the symptoms of abnormal uterine bleeding and dysmenorrhea were markedly relieved, which raises a question about the role that the LNG-IUD played. The direct effect of levonorgestrel on the foci of the adenomyosis can affect the progesterone receptor, which produces a profound effect on the eutopic endometrium that becomes atrophic and inactive[10]. The consequences are hypomenorrhea and even amenorrhoea. In this unique case, levonorgestrel probably acted directly on the endometriotic lesions and on the normal endometrium via haematogenous or lymphatic pathways to reduce bleeding[11,12]. In addition, LNG-IUDs may also emerge as a good method for the reduction of pelvic vascular congestion[13], inhibition of the inflammatory mediators, and reduction of macrophage activity present in the peritoneum to control pain associated with endometriosis[14].

Myomectomy breaking through the endometrial cavity may be a predisposing factor for the development of adenomyosis. In terms of management, laparoscopic uterine-sparing interventions may be the preferable choice for exophytic cystic adenomyosis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mais V, Verma S S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Fan YY, Liu YN, Li J, Fu Y. Intrauterine cystic adenomyosis: Report of two cases. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:676-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Koninckx PR, Ussia A, Adamyan L, Wattiez A, Gomel V, Martin DC. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: the genetic/epigenetic theory. Fertil Steril. 2019;111:327-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kamio M, Taguchi S, Oki T, Tsuji T, Iwamoto I, Yoshinaga M, Douchi T. Isolated adenomyotic cyst associated with severe dysmenorrhea. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2007;33:388-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tan J, Yong P, Bedaiwy MA. A critical review of recent advances in the diagnosis, classification, and management of uterine adenomyosis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;31:212-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kazemi E, Alavi A, Aalinezhad F, Jahanshahi K. Evaluation of the relationship between prior uterine surgery and the incidence of adenomyosis in the Shariati Hospital in Bandar-Abbas, Iran, from 2001 to 2011. Electron Physician. 2014;6:912-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mehasseb MK, Panchal R, Taylor AH, Brown L, Bell SC, Habiba M. Estrogen and progesterone receptor isoform distribution through the menstrual cycle in uteri with and without adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2228-2235, 2235.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Munro MG. Uterine polyps, adenomyosis, leiomyomas, and endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril. 2019;111:629-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gordts S, Grimbizis G, Campo R. Symptoms and classification of uterine adenomyosis, including the place of hysteroscopy in diagnosis. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:380-388.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brosens I, Gordts S, Habiba M, Benagiano G. Uterine Cystic Adenomyosis: A Disease of Younger Women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28:420-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Philip S, Taylor AH, Konje JC, Habiba M. The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device induces endometrial decidualisation in women on tamoxifen. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;39:1117-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim CR, Martinez-Maza O, Magpantay L, Magyar C, Gornbein J, Rible R, Sullivan P. Immunologic evaluation of the endometrium with a levonorgestrel intrauterine device in solid organ transplant women and healthy controls. Contraception. 2016;94:534-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lockhat FB, Emembolu JE, Konje JC. Serum and peritoneal fluid levels of levonorgestrel in women with endometriosis who were treated with an intrauterine contraceptive device containing levonorgestrel. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:398-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rezk M, Elshamy E, Shaheen AE, Shawky M, Marawan H. Effects of a levonorgestrel intrauterine system versus a copper intrauterine device on menstrual changes and uterine artery Doppler. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;145:18-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Labied S, Galant C, Nisolle M, Ravet S, Munaut C, Marbaix E, Foidart JM, Frankenne F. Differential elevation of matrix metalloproteinase expression in women exposed to levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for a short or prolonged period of time. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:113-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |