Published online Jan 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i1.103

Peer-review started: October 18, 2019

First decision: November 4, 2019

Revised: November 12, 2019

Accepted: November 20, 2019

Article in press: November 20, 2019

Published online: January 6, 2020

Processing time: 80 Days and 4.2 Hours

Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation (SANT) is a rare benign disease of the spleen with unknown origin. Clinical symptoms are inhomogeneous, and suspicious splenic lesion often found incidentally, leading to splenectomy, as malignancy cannot securely be ruled out. Diagnosis is made histologically after resection.

Two cases of German, white, non-smoking, and non-drinking patients of normal weight are presented. The first one is a 26-year-old man without medical history who was exhibiting an undesired weight loss of 10 kg and recurring vomiting for about 18 mo. The second one is a 65-year-old woman with hypertension who had previously undergone gynecological surgery, suffering from a lasting feeling of abdominal fullness. Both showed radiologically an inhomogeneous splenic lesion leading to splenectomy approximately 6 and 9 wk after surgical presentation. Both diagnoses of SANT were made histologically. Follow-up went well, and both were treated according to the recommendation for asplenic patients.

SANT is a rare cause of splenectomy and an incidental histological finding. Further research should focus on clinical and radiological diagnosis of SANT as well as on treatment of patients with asymptomatic and small findings.

Core tip: We are presenting two cases of clinical evident sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation (SANT) and discuss the challenge of clinical non-operative management of small and asymptomatic splenic lesions. SANT is a benign vascular lesion of unknown etiology occurring in the spleen and does not appear to be related to age, gender, or pre-existing illnesses, although some reports have reported a higher frequency in women. SANT is an incidental histologically finding after splenectomy, and there is no guideline for treatment of SANT.

- Citation: Chikhladze S, Lederer AK, Fichtner-Feigl S, Wittel UA, Werner M, Aumann K. Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation of the spleen, a rare cause for splenectomy: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(1): 103-109

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i1/103.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i1.103

Abdominal discomfort and gastrointestinal dysfunction are common reasons for a doctor’s consultation. Nearly a third of acute cases appear to be nonspecific without any organic lesion being causative for the complaint[1]. Long-lasting symptoms lead to a variety of diagnostic procedures, which in turn often lead to incidental findings[2]. A really rare incidental finding is sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation (SANT) of the spleen. SANT is a benign vascular lesion of unknown etiology occurring in the spleen and was first described in 2004[3]. SANT does not appear to be related to age, gender, or pre-existing illnesses, although some reports have reported a higher frequency in women[4]. Some patients with SANT complain about abdominal discomfort, which often includes nausea and vomiting, as well as nausea, vomiting, and occasional malnutrition[3,5,6]. As a vascular and splenic tumor, SANT might lead to anemia or anemia-related fatigue[3,7,8]. Contrarily, some patients can be asymptomatic[3-5,9,10]. SANT is often clinically and radiologically confused with hemangioma or hamartoma[9] and can only be proven histologically[3,8]. Because of the supposed increased risk of a spontaneous rupture of large vascular splenic lesions and the risk for a possible malignancy of the suspicious lesion, splenectomy should be performed[11]. Recent publications have focused on pathologic findings, which is why we overview the clinical symptoms and surgical treatment of SANT with the help of two case reports.

According to the CARE guidelines for publication of case reports[12], this report covers two patients with histologically proven SANT of the spleen who underwent splenectomy at the Department of General and Visceral Surgery of the University Medical Center of Freiburg, Germany.

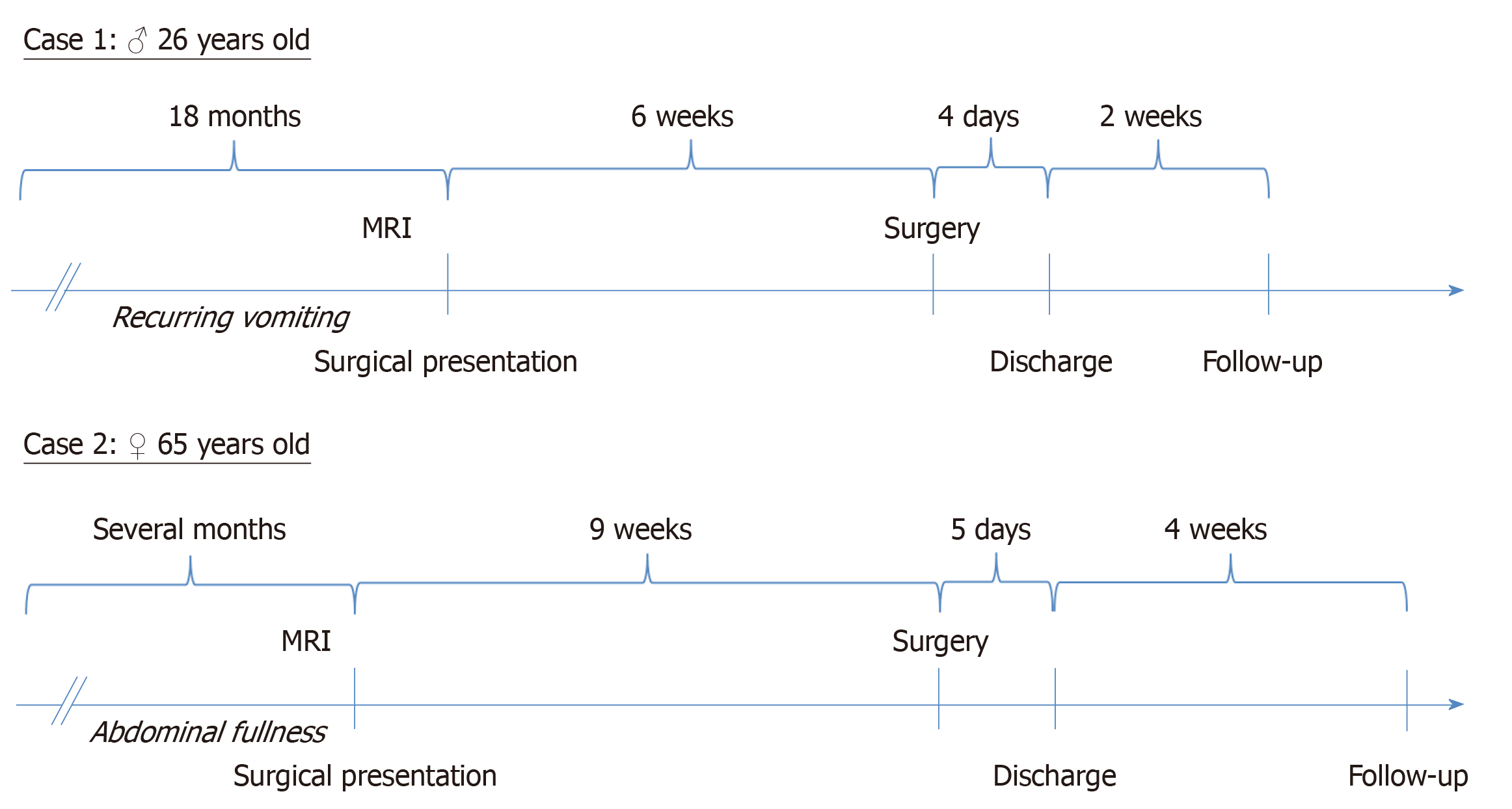

Case 1: A 26-year-old Caucasian, non-smoking, and non-drinking man (175 cm, 65 kg, body mass index: 21.2 kg/m2) exhibiting an undesired weight loss of 10 kg and recurring vomiting for about 18 mo.

Case 2: A 65-year-old Caucasian, non-smoking, and non-drinking woman (150 cm, 50 kg) presented with a lasting feeling of abdominal fullness.

Case 1: Physical examination and initial gastroenterological evaluation as well as tests for food intolerances revealed no pathologic results. Intake of medication to alleviate symptoms was negated.

Case 2: Physical examination showed normal findings, and the initial gastroenterological evaluation revealed no pathologic results. Intake of medication to alleviate symptoms was negated.

Case 1: Nothing to declare.

Case 2: Patient suffered from hypertension (prescribed with once daily medication of candesartan 4 mg) and underwent previous gynecological surgery (curettage and polypectomy).

Case 1: Nothing to declare.

Case 2: Family history showed one case of melanoma (father) and one case of breast cancer (sister).

Case 1: Abdomen magnetic resonance imaging showed a 46 mm × 41 mm × 44 mm heterogeneous solid mass of the spleen. According to the magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis, it was most likely a thrombosed hemangioma.

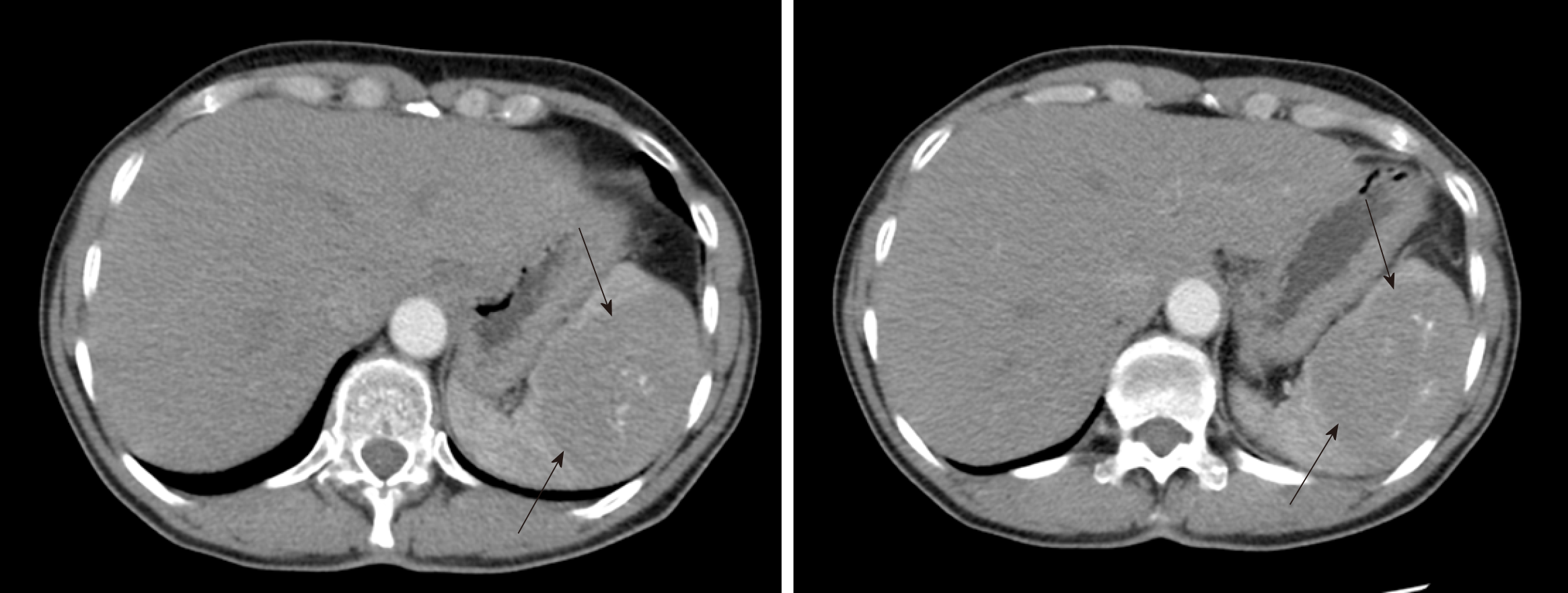

Case 2: Abdomen computed tomography showed a 74 mm × 54 mm heterogeneous solid mass of the spleen appearing to be an angiosarcoma rather than a hemangioma (Figure 1). Furthermore, a suspicious lesion of the pancreas, most likely an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, was found.

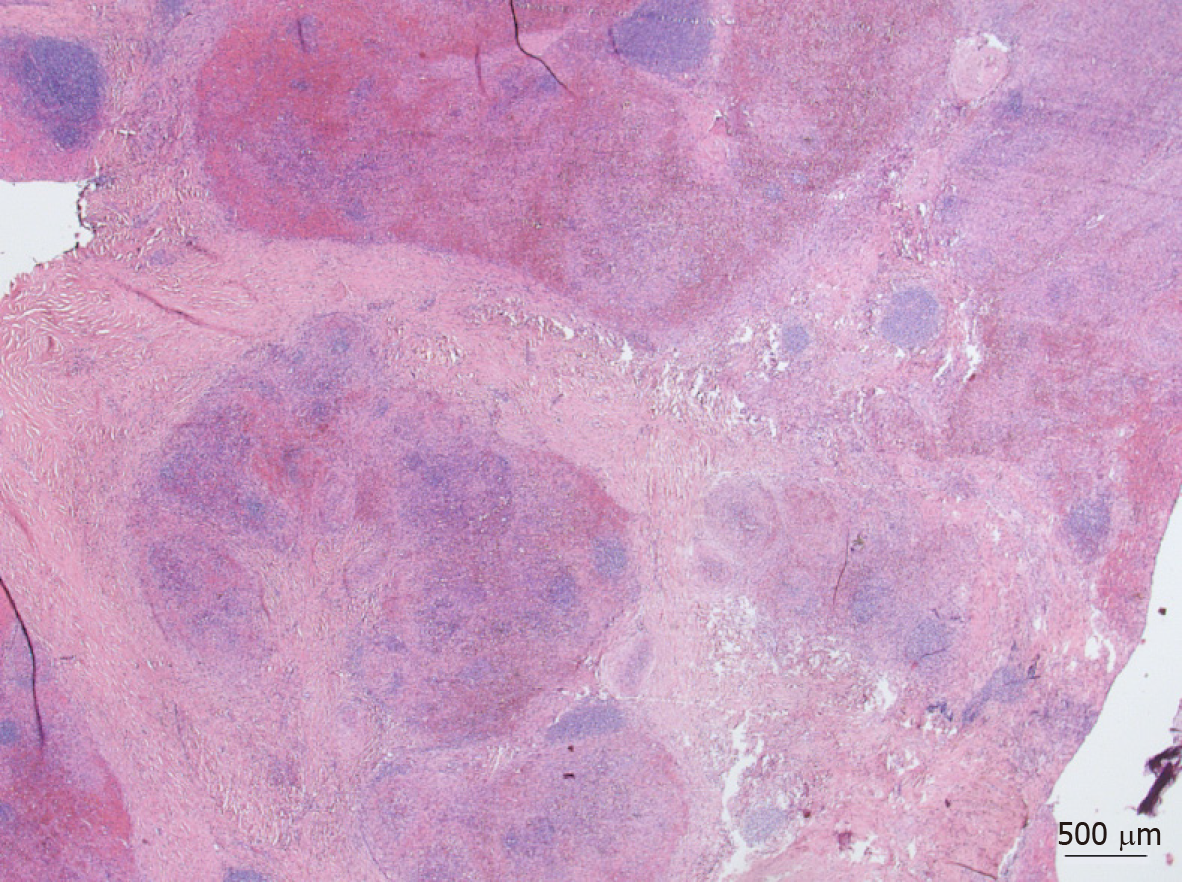

Grossly, the spleen was enlarged to 140 mm × 82 mm × 43 mm due to a solitary lesion, 41 mm × 37 mm × 32 mm, sharply demarcated and composed of red-brown nodules in dense fibrous stroma (Figure 2). The spleen weighed 260 g. Histologically, the lesion appeared micronodularly with slit-like and irregular shaped vascular spaces lined by inconspicuous endothelial cells. Stroma contained dense fibrous tissue with scattered myofibroblasts, inflammatory cells, and numerous red blood cells. The nodules were surrounded by dense collagen fibers. Increased immunoglobulin G4-positive plasma cell population was not found. Neither necrosis nor atypia was seen, and the mitotic rate was very low. By RNA in situ hybridization, Epstein-Barr virus was not detectable. The diagnosis of SANT was rendered.

The spleen was 105 mm × 82 mm × 59 mm, widely fibrotic, and scarred, showing calcification and residuals of old bleedings in an intact capsule. The spleen weighed 198 g. Histologically, the lesion presented tumorous proliferation of partly nodular, partly lobular endothelial cells with diffuse lymphohistiocytic infiltration, distinct sclerosis, and extensive hystiocytic aggregates with displacement of local parenchyma. Increased immunoglobulin G4-positive plasma cell population was found. Neither necrosis nor atypia was seen, mitotic rate was very low. By RNA in situ hybridization, Epstein-Barr virus was not detectable. The diagnosis of SANT was made.

Surgical presentation led to the indication for laparoscopic splenectomy. The patient consented to surgical resection and was recommended to consult his family doctor before operation to be vaccinated against Haemophilus influenza, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Neisseria meningitidis, according to the guideline for asplenic patients[13].

Operation was performed electively in general anesthesia approximately 6 wk after surgical presentation (Figure 3). Inspection of abdomen revealed no further pathologies. Patient showed an accessory spleen, which was not removed. Operation was performed as previously described by others[14,15]. After complete laparoscopic mobilization of the spleen, a 4 cm median laparotomy of the upper abdomen was performed to retrieve the organ in a retrieval bag. Operation lasted 106 min, and bleeding was minimal. Patient was taken to the post anesthesia care unit after operation. Patient did well following surgery and was discharged on the 4th postoperative day.

Surgical presentation led to an indication for laparoscopic splenectomy. Patient was recommended to consult her family doctor for necessary vaccinations before operation.

Operation was performed electively under general anesthesia approximately 9 wk after surgical presentation (Figure 3). Inspection of abdomen revealed no further pathologies. As mentioned above, operation was performed as it was previously described by others[14,15]. After complete laparoscopic mobilization, the spleen was placed in a retrieval bag. For the removal of the former, Pfannenstiel’s incision was used. Patient received a drain, localized in the left-sided upper abdomen. Operation lasted 88 min, and bleeding was approximately 50 mL. After operation, the patient was taken to the post anesthesia care unit. Patient did well following surgery and was discharged on the 5th postoperative day.

Patient was seen again 2 wk after operation. Physical examination showed normal findings, recovery appeared to be proper, and patient felt subjectively healthy. Weight was stable (65 kg, body mass index: 21.2 kg/m2). Examination of blood sample showed thrombocytosis of 662,000/µL and Howell-Jolly bodies as a sign of an asplenic situation[16,17]. Two weeks later, the patient returned and showed a small wound healing disorder due to a suture granuloma. The wound was re-opened, the suture was removed, and the wound was re-adapted with patches.

Patient was seen again 4 wk after operation. Physical examination showed normal findings, recovery appeared to be proper, and patient felt subjectively healthy. Weight was stable (50 kg, body mass index: 22.2 kg/m2). Measurement of blood samples revealed normal findings with exception of Howell-Jolly bodies as a sign of an asplenic situation[16,17].

The occurrence of SANT is very low, with only a few hundred cases world-wide. SANT was first termed in 2004 by Martel et al[3], who were able to collect 25 cases of SANT. The histological features of SANT were described years before in a few case reports but never designated as SANT[9]. Although our hospital is a high-volume surgical center, we found only two cases of SANT in our archives between 2004 and 2019. SANT can be well differentiated from other benign lesions histologically[4], but it appears that it is not possible to differentiate SANT clinically. Fine needle aspiration of spleen is necessary due to the risk of peritoneal spreading of a potential malignant lesion and a high risk of post-interventional bleedings is not preferable. Imaging methods often misdiagnose SANT as hemangioma, hamartoma, or, as in one of our cases, malignancy. One case of SANT showed a minimally lower attenuation on unenhanced computed tomography images and hypoattenuation during hepatic arterial and the portal venous phase with an undulating peripheral enhancement compared to normal splenic tissue[6]. Furthermore, contrast enhanced imaging showed nearly an isodense lesion with an unenhanced central stellate area, which is slightly different from other solid masses of the spleen[6]. Hemangioma normally shows a homogeneous and marked contrast enhancement[18]. Differentiation of hamartoma is a bit more difficult as it can be inhomogeneous, showing just a contour abnormality[18]. Further splenic tumors are known, although their radiological diagnoses need not be mentioned in detail here. Generally, the differentiation of solid masses of the spleen is challenging, and misdiagnoses are not surprising due to the variety of splenic tumors.

To our knowledge, nothing is known about the risk of rupture of SANT. Vascular lesions of the spleen, such as hemangioma, are often discussed to be at an increased risk of rupture, and are, therefore, rapidly resected. The recommendation for this procedure is almost 60-years-old[11], and others indicated that it might be possible to observe patients with small, asymptomatic lesions[19]. A systematic review of splenic rupture reports of patients without known risk factors for splenic rupture showed only eight hemangioma and hamartoma cases out of 613 reviewed cases (1.3%) as a reason for rupture[20]. Nevertheless, not only the risk of rupture remains unclear, it is also unclear whether SANT might develop malignant transformation. To date, no case of recurrence of SANT has been reported. Our patients received a short-term after-care of less than 2 years, but they showed no signs of recurrence so far. Surgical resection appears to be a curative response to SANT, restraining the risk of rupture and malignant transformation. Whether it is even necessary, especially for asymptomatic and small cases, remains unclear. As SANT is often an incidental finding, most of the patients are asymptomatic, leading to the question if routine observation might be an alternative. The morbidity rate of splenectomy is approximately 30%, and mortality rate is even up to 15%, depending upon patients’ condition and indication for splenectomy[21,22]. Splenectomy has a high risk for intra- and postoperative hemorrhages[22].

The major long-term risk is an overwhelming post-splenectomy infection with an increased risk of fulminant infection, caused by encapsulated bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae[17]. Mortality of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI) is up to 70%[23]. Nowadays, OPSI is preventable by vaccination, but it is reported that only two-thirds of post-splenectomy patients followed vaccination recommendations and that there are still known deadly cases of vaccination-preventable OPSI[24,25]. Awareness of intra- and postoperative complications of splenectomy is necessary before indicating surgery. There is no doubt that rupture is a life-threatening event, but the risk level of rupture, as well as the risk of malignancy of SANT, remains unclear, and it is, therefore, difficult to estimate the risk-ratio of operation, post-splenectomy living, and occurrence of rupture. It is supposable that most patients were surgically treated due to an unclarified, possibly malignant lesion and not to an occurrence of symptoms. Symptomatic patients might benefit from surgical resection. Difficulty to eat, as stated by our patients, is also reported to be typically observed in patients with SANT[3,5,6]. The symptomatology appears to be plausible in large findings as Figure 2 of Case 2 shows obstructive displacement of the stomach. Severe and acute life-threatening cases of SANT are extremely rare[26], and it is not known if they might be preventable by an early surgical resection. In summary, further research has to focus on improvement of clinical and radiological diagnosis of SANT and on evaluation of the clinical course of SANT. It has to be clarified whether it is possible to observe patients with small and asymptomatic vascular lesions of the spleen or if surgery is always necessary.

SANT is a rare cause for splenectomy and an incidental histological finding. Some patients develop non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms insecurely related to SANT. Severe cases of SANT are extremely rare. Splenectomy is a promising curative therapeutic approach for SANT. Further research should focus on clinical and radiological diagnosis of SANT as well as on treatment of patients with asymptomatic and small findings.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Krishna S, Lv Y, Peng B, Slomiany BL S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Cervellin G, Mora R, Ticinesi A, Meschi T, Comelli I, Catena F, Lippi G. Epidemiology and outcomes of acute abdominal pain in a large urban Emergency Department: retrospective analysis of 5,340 cases. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bluemke DA, Liu S. Imaging in Clinical Trials. In: Principles and Practice of Clinical Research. Netherlands: Elsevier 2012; 597–617. |

| 3. | Martel M, Cheuk W, Lombardi L, Lifschitz-Mercer B, Chan JK, Rosai J. Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation (SANT): report of 25 cases of a distinctive benign splenic lesion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1268-1279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | El Demellawy D, Nasr A, Alowami S. Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation of the spleen: case report. Pathol Res Pract. 2009;205:289-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Niu M, Liu A, Wu J, Zhang Q, Liu J. Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation of the accessory spleen: A case report and review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zeeb LM, Johnson JM, Madsen MS, Keating DP. Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:W236-W238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ajmal A, Fadia M. Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation of spleen (SANT)–case report and literature review. Pathology. 2015;47:S59. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Diebold J, Le Tourneau A, Marmey B, Prevot S, Müller-Hermelink HK, Sevestre H, Molina T, Billotet C, Gaulard P, Knopf JF, Bendjaballah S, Mangnan-Marai A, Brière J, Fabiani B, Audouin J. Is sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation (SANT) of the splenic red pulp identical to inflammatory pseudotumour? Report of 16 cases. Histopathology. 2008;53:299-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cao P, Wang K, Wang C, Wang H. Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation in the spleen: A case series study and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e15154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dazé Y, Gosselin J, Bernier V. [Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation of the spleen (SANT): a case report]. Ann Pathol. 2008;28:321-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | HUSNI EA. The clinical course of splenic hemangioma with emphasis on spontaneous rupture. Arch Surg. 1961;83:681-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Riley DS, Barber MS, Kienle GS, Aronson JK, von Schoen-Angerer T, Tugwell P, Kiene H, Helfand M, Altman DG, Sox H, Werthmann PG, Moher D, Rison RA, Shamseer L, Koch CA, Sun GH, Hanaway P, Sudak NL, Kaszkin-Bettag M, Carpenter JE, Gagnier JJ. CARE guidelines for case reports: explanation and elaboration document. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:218-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 741] [Cited by in RCA: 1022] [Article Influence: 127.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rubin LG, Schaffner W. Clinical practice. Care of the asplenic patient. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:349-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Borie F. Laparoscopic partial splenectomy: Surgical technique. J Visc Surg. 2016;153:371-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fisichella PM, Wong YM, Pappas SG, Abood GJ. Laparoscopic splenectomy: perioperative management, surgical technique, and results. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:404-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sears DA, Udden MM. Howell-Jolly bodies: a brief historical review. Am J Med Sci. 2012;343:407-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Di Sabatino A, Carsetti R, Corazza GR. Post-splenectomy and hyposplenic states. Lancet. 2011;378:86-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 412] [Cited by in RCA: 438] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Abbott RM, Levy AD, Aguilera NS, Gorospe L, Thompson WM. From the archives of the AFIP: primary vascular neoplasms of the spleen: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2004;24:1137-1163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Willcox TM, Speer RW, Schlinkert RT, Sarr MG. Hemangioma of the spleen: presentation, diagnosis, and management. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:611-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Aubrey-Bassler FK, Sowers N. 613 cases of splenic rupture without risk factors or previously diagnosed disease: a systematic review. BMC Emerg Med. 2012;12:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Moris D, Dimitriou N, Griniatsos J. Laparoscopic Splenectomy for Benign Hematological Disorders in Adults: A Systematic Review. In Vivo. 2017;31:291-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Weledji EP. Benefits and risks of splenectomy. Int J Surg. 2014;12:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Holdsworth RJ, Irving AD, Cuschieri A. Postsplenectomy sepsis and its mortality rate: actual versus perceived risks. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1031-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 343] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Di Sabatino A, Lenti MV, Tinozzi FP, Lanave M, Aquino I, Klersy C, Marone P, Marena C, Pietrabissa A, Corazza GR. Vaccination coverage and mortality after splenectomy: results from an Italian single-centre study. Intern Emerg Med. 2017;12:1139-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Blumentrath CG, Ewald N, Petridou J, Werner U, Hogan B. The sword of Damocles for the splenectomised: death by OPSI. Ger Med Sci. 2016;14:Doc10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pelizzo G, Villanacci V, Lorenzi L, Doria O, Caruso AM, Girgenti V, Unti E, Putignano L, Bassotti G, Calcaterra V. Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation presenting with abdominal hemorrhage: First report in infancy. Pediatr Rep. 2019;11:7848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |