Published online May 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i9.1028

Peer-review started: February 18, 2019

First decision: March 5, 2019

Revised: March 15, 2019

Accepted: March 26, 2019

Article in press: March 26, 2019

Published online: May 6, 2019

Processing time: 79 Days and 19 Hours

Recurrence of primary choledocholithiasis commonly occurs after complete removal of stones by therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The potential causes of the recurrence of choledocholithiasis after ERCP are unclear.

To analyze the potential causes of the recurrence of choledocholithiasis after ERCP.

The ERCP database of our medical center for the period between January 2007 and January 2016 was retrospectively reviewed, and information regarding eligible patients who had choledocholithiasis recurrence was collected. A 1:1 case-control study was performed for this investigation. Data including general characteristics of the patients, past medical history, ERCP-related factors, common bile duct (CBD)-related factors, laboratory indicators, and treatment was analyzed by univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis and Kaplan-Meier analysisly.

First recurrence of choledocholithiasis occurred in 477 patients; among these patients, the second and several instance (≥ 3 times) recurrence rates were 19.5% and 44.07%, respectively. The average time to first choledocholithiasis recurrence was 21.65 mo. A total of 477 patients who did not have recurrence were selected as a control group. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that age > 65 years (odds ratio [OR] = 1.556; P = 0.018), combined history of choledocholithotomy (OR = 2.458; P < 0.01), endoscopic papillary balloon dilation (OR = 5.679; P = 0.000), endoscopic sphincterotomy (OR = 3.463; P = 0.000), CBD stent implantation (OR = 5.780; P = 0.000), multiple ERCP procedures (≥2; OR = 2.75; P = 0.000), stones in the intrahepatic bile duct (OR = 2.308; P = 0.000), periampullary diverticula (OR = 1.627; P < 0.01), choledocholithiasis diameter ≥ 10 mm (OR = 1.599; P < 0.01), bile duct-duodenal fistula (OR = 2.69; P < 0.05), combined biliary tract infections (OR = 1.057; P < 0.01), and no preoperative antibiotic use (OR = 0.528; P < 0.01) were independent risk factors for the recurrence of choledocholithiasis after ERCP.

Patient age greater than 65 years is an independent risk factor for the development of recurrent choledocholithiasis following ERCP, as is history of biliary surgeries, measures during ERCP, and prevention of postoperative complications.

Core tip: The potential causes of the recurrence of choledocholithiasis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are unclear. By a large sample sized retrospective study of 954 patients, we concluded that patient age greater than 65 years is an independent risk factor for the development of recurrent choledocholithiasis following ERCP, as is history of biliary surgeries, measures during ERCP, and prevention of postoperative complications.

- Citation: Deng F, Zhou M, Liu PP, Hong JB, Li GH, Zhou XJ, Chen YX. Causes associated with recurrent choledocholithiasis following therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A large sample sized retrospective study. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(9): 1028-1037

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i9/1028.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i9.1028

Due to its minimal trauma and high safety, endoscopic retrograde cholan-giopancreatography (ERCP) has become one of the most important methods for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of choledocholithiasis. Currently, ERCP technology is very advanced, but the recurrence of choledocholithiasis after ERCP is still a challenging problem. Follow-up studies have shown that the incidence of choledocholithiasis recurrence after endoscopic treatment is 2%-22%[1-5]. Many studies have reported that choledocholithiasis is associated with bacterial infection, an abnormal biliary structure, inflammation, endoscopic and surgical treatment, and other factors[1-3,6-8]. However, risk factors for the recurrence of choledocholithiasis have not been thoroughly defined, and the risk factors identified are different across studies. This study aimed to explore the independent risk factors for stone recurrence by comprehensively analyzing the relevant factors for stone recurrence in a large-sized sample.

From January 2007 to January 2016, we retrospectively reviewed cases from a well-designed ERCP database at the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. The follow-up period was from the date of the initial removal of choledocholithiasis to the date of the visit to the hospital for choledocholithiasis recurrence or more than one year for the control group. The patients with the symptoms of fever, abdominal pain, jaundice, or other typical symptoms who revisited our hospital underwent abdominal computed tomography (CT) and ERCP to confirm choledocholithiasis. The patients who underwent choledocholithiasis removal by ERCP and were confirmed to have had their stones completely removed were enrolled. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) History of previous ERCP; (2) Patients with tumors of the liver, gallbladder, common bile duct (CBD), or duodenal papilla; (3) Patients were confirmed not to have had their stones completely removed after first chole-docholithiasis removal by ERCP; and (4) Patients with incomplete clinical data. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (No. 2017-040).

The primary outcomes were risk factors for recurrence of choledocholithiasis. Choledocholithiasis recurrence was defined as recurrence of symptoms of fever, abdominal pain, jaundice, or other typical symptoms, and choledocholithiasis was confirmed by abdominal B-scan ultrasonography, CT, or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography 6 mo after the stones were completely removed. The patients were classified into two groups: Recurrence and control groups. The following clinical data were recorded: (1) General characteristics, including sex, age, time from disease onset to stone removal, and history of drinking and smoking; (2) Past medical history, including history of hypertension, diabetes, hepatitis B, fatty liver, cirrhosis, cholecystectomy, biliary-enteric anastomosis, choledocholithotomy, or Billroth II gastrectomy; (3) ERCP-related factors, including endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy (EML), endoscopic papillary balloon dilation (EPBD), endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), CBD stent implantation, endoscopic nasobiliary drainage, and the number of ERCP procedures; (4) CBD-related factors, including the presence of a combined biliary tract infection, gallstones, stones in the intrahepatic bile duct, a bile duct-duodenal fistula, CBD stenosis, duodenal ulcers, periampullary diverticula (PAD) or ectopic duodenal papilla, duodenal papilla shape, bile duct angle referring to the angle between the horizontal part of the CBD and a horizontal line[9], common bile diameter, CBD diameter, and the number of stones; and (5) Laboratory indicators and treatment, including total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, gallbladder parameters, triglycerides, and the use of preoperative antibiotics.

Continuous variables are reported as the mean and standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables are reported as absolute numbers and percentages. Variables found to be statistically significant in the univariate logistic regression analysis were introduced into a multivariate logistic analytic model (stepwise regression) to identify independent risk factors with odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS software (v17.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

From January 2007 to January 2016, 477 patients revisited the hospital for their choledocholithiasis recurrence. Among these patients, the second and several instance (≥ 3 times) recurrence rates were 19.5% (93/477) and 44.07% (41/477), respectively. The average number of instances of stone recurrence was 1.45, and the average time to first stone recurrence was 21.65 mo. A 1:1 case-control study was used for this investigation, and the controls were 477 patients without choledocholithiasis recurrence after ERCP in more than one year of follow-up. The average age of all patients was 57.43 ± 14.92 years, and the study included 445 males (46.65%) and 509 females (53.35%). There were more patients > 65 years old in the recurrence group than in the control group (OR = 2.437, 95%CI: 1.818-3.266; P = 0.000). No statistically significant differences between the two groups were observed in terms of sex, weight, time from the onset of stone removal to recurrence, or history of drinking or smoking (Table 1).

| Variable | Recurrence group (n = 477) | Control group (n = 477) | OR (95%CI) | P-value |

| Sex (male/female) | 216/261 | 229/248 | 1.116 (0.865-1.439) | 0.399 |

| Age > 65 yr (Y/N) | 181/296 | 134/343 | 2.437 (1.818-3.266) | 0.000 |

| Weight (kg), mean ± SD | 57.94 ± 16.80 | 58.24 ± 11.31 | 0.992 (0.980-1.004) | 0.196 |

| 1Recurrence time (d), mean ± SD | 17.77 ± 19.30 | 17.85 ± 17.25 | 1.000 (0.993-1.007) | 0.950 |

| History of drinking (Y/N) | 42/423 | 61/416 | 0.677 (0.447-1.026) | 0.066 |

| History of smoking (Y/N) | 69/395 | 86/391 | 0.794 (0.562-1.123) | 0.192 |

On univariate analysis, significant differences were noted between the two groups in terms of medical history: A medical history of cholecystectomy (OR = 1.4, 95%CI: 1.085-1.806; P = 0.01) and choledocholithotomy (OR = 3.255, 95%CI: 2.114-5.01; P = 0.000) (Table 2). Moreover, significant differences in ERCP-related factors were observed: ERCP with EML (OR = 2.068, 95%CI: 1.375-3.11; P = 0.000), EPBD (OR = 5.669, 95%CI: 3.594-8.941; P = 0.000), EST (OR = 1.701, 95%CI: 1.197-2.417; P = 0.003), CBD stent implantation (OR = 3.737, 95%CI: 2.587-5.398; P = 0.000), and multiple ERCP procedures (OR = 3.043, 95%CI: 2.242-4.13; P = 0.000) (Table 3). CBD-related factors, such as complications including biliary tract infections (OR = 1.034, 95%CI: 1.007-1.061; P = 0.014), stones in the intrahepatic bile duct (OR = 2.687, 95%CI: 1.919-3.762; P = 0.000), PAD (OR = 1.607, 95%CI: 1.227-2.105; P = 0.001), bile-duct duodenal fistula (OR = 2.324, 95%CI: 1.088-4.964; P < 0.05), CBD stenosis (OR = 1.661, 95%CI: 1.051-2.626; P < 0.05), CBD diameter (OR = 1.988, 95%CI: 1.589-2.486; P = 0.000), and choledocholithiasis diameter ≥ 10 mm (OR = 1.580, 95%CI: 1.202-2.067; P = 0.001) also showed significant differences between the two groups (Table 4). Additionally, compared with patients in the control group, patients in the recurrence group used fewer antibiotics before ERCP (OR = 0.523, 95%CI: 0.385-0.711; P = 0.000) (Table 5).

| Variable | Recurrence group (n = 477) | Control group (n = 477) | OR (95%CI) | P-value |

| Hypertension (Y/N) | 84/393 | 63/414 | 1.405 (0.985-2.002) | 0.060 |

| Diabetes (Y/N) | 34/441 | 26/452 | 1.334 (0.788-2.261) | 0.284 |

| Hepatitis B (Y/N) | 37/440 | 34/438 | 1.083 (0.668-1.758) | 0.746 |

| Fatty liver (Y/N) | 15/462 | 23/454 | 0.641 (0.330-1.244) | 0.189 |

| Liver cirrhosis (Y/N) | 17/460 | 10/461 | 1.704 (0.772-3.760) | 0.187 |

| Cholecystectomy (Y/N) | 252/225 | 212/265 | 1.400 (1.085-1.806) | 0.010 |

| Biliary-enteric anastomosis (Y/N) | 5/471 | 2/475 | 2.521 (0.487-13.06) | 0.270 |

| Choledocholithotomy (Y/N) | 88/389 | 31/446 | 3.255 (2.114-5.010) | 0.000 |

| Variable | Recurrence group (n = 477) | Control group (n = 477) | OR (95%CI) | P-value |

| EML (Y/N) | 74/391 | 40/437 | 2.068 (1.375-3.110) | 0.000 |

| EPBD (Y/N) | 111/345 | 25/461 | 5.669 (3.594-8.941) | 0.000 |

| EST (Y/N) | 404/60 | 382/96 | 1.701 (1.197-2.417) | 0.003 |

| CBD stent implantation (Y/N) | 130/334 | 45/432 | 3.737 (2.587-5.398) | 0.000 |

| ENBD (Y/N) | 271/192 | 282/195 | 0.976 (0.753-1.266) | 0.855 |

| ERCP procedures, mean ± SD | 1.38 ± 0.55 | 1.14 ± 0.39 | 3.043 (2.242-4.130) | 0.000 |

| Variable | Recurrence group (n = 477) | Control group (n = 477) | OR (95%CI) | P-value |

| Gallstones (Y/N) | 274/203 | 272/205 | 1.017 (0.787-1.315) | 0.896 |

| Intrahepatic bile duct stones (Y/N) | 133/344 | 60/417 | 2.687 (1.919-3.762) | 0.000 |

| Ectopic duodenal papilla (Y/N) | 3/462 | 1/476 | 3.091 (0.32-29.822) | 0.329 |

| Duodenal ulcers (Y/N) | 21/443 | 26/451 | 0.822 (0.456-1.483) | 0.516 |

| PAD (Y/N) | 188/276 | 142/335 | 1.607 (1.227-2.105) | 0.001 |

| Bile duct angle (Y/N) | 36/429 | 25/452 | 1.517 (0.896-2.570) | 0.121 |

| CBD diameter (cm), mean ± SD | 1.27±0.73 | 1.01±0.55 | 1.988 (1.589-2.486) | 0.000 |

| Choledocholithiasis diameter ≥ 10 mm (Y/N) | 229/134 | 126/236 | 1.580 (1.202-2.067) | 0.001 |

| Number of stones (n), (mean ± SD) | 1.90 ± 1.19 | 1.82 ± 1.02 | 1.12 (0.992-1.265) | 0.067 |

| Biliary tract infections (Y/N) | 46/418 | 20/457 | 2.515 (1.463-4.321) | 0.001 |

| Bile-duct duodenal fistula (Y/N) | 22/442 | 10/467 | 2.324 (1.088-4.964) | 0.029 |

| CBD stenosis (Y/N) | 51/413 | 33/444 | 1.661 (1.051-2.626) | 0.030 |

| Variable | Recurrence group (n = 477) | Control group (n = 477) | OR (95%CI) | P-value |

| TBi (umol/L), mean ± SD | 53.02 ± 69.91 | 102.47 ± 126.1 | 1.000 (0.999-1.001) | 0.795 |

| DBi (umol /L), mean ± SD | 31.41 ± 44.64 | 71.21 ± 126.1 | 1.000 (0.998-1.002) | 0.961 |

| ALT (U/L), mean ± SD | 129.3 ± 142.91 | 98.39 ± 127.62 | 0.999 (0.998-1.000) | 0.201 |

| AST (U/L), mean ± SD | 96.99 ± 132.68 | 64.86 ± 103.69 | 0.999 (0.998-1.000) | 0.123 |

| GGT (U/L), mean ± SD | 288.3 ± 262.92 | 306.3 ± 267.96 | 1.000 (1.000-1.001) | 0.441 |

| Cholesterol (mmol /L), mean ± SD | 4.77 ± 14.09 | 4.33 ± 1.53 | 0.990 (0.886-1.105) | 0.852 |

| Triglyceride (mmol /L), mean ± SD | 1.30 ± 0.82 | 1.43 ± 0.85 | 0.888 (0.742-1.063) | 0.197 |

| Used antibiotics before ERCP (Y/N) | 336/141 | 387/85 | 0.523 (0.385-0.711) | 0.000 |

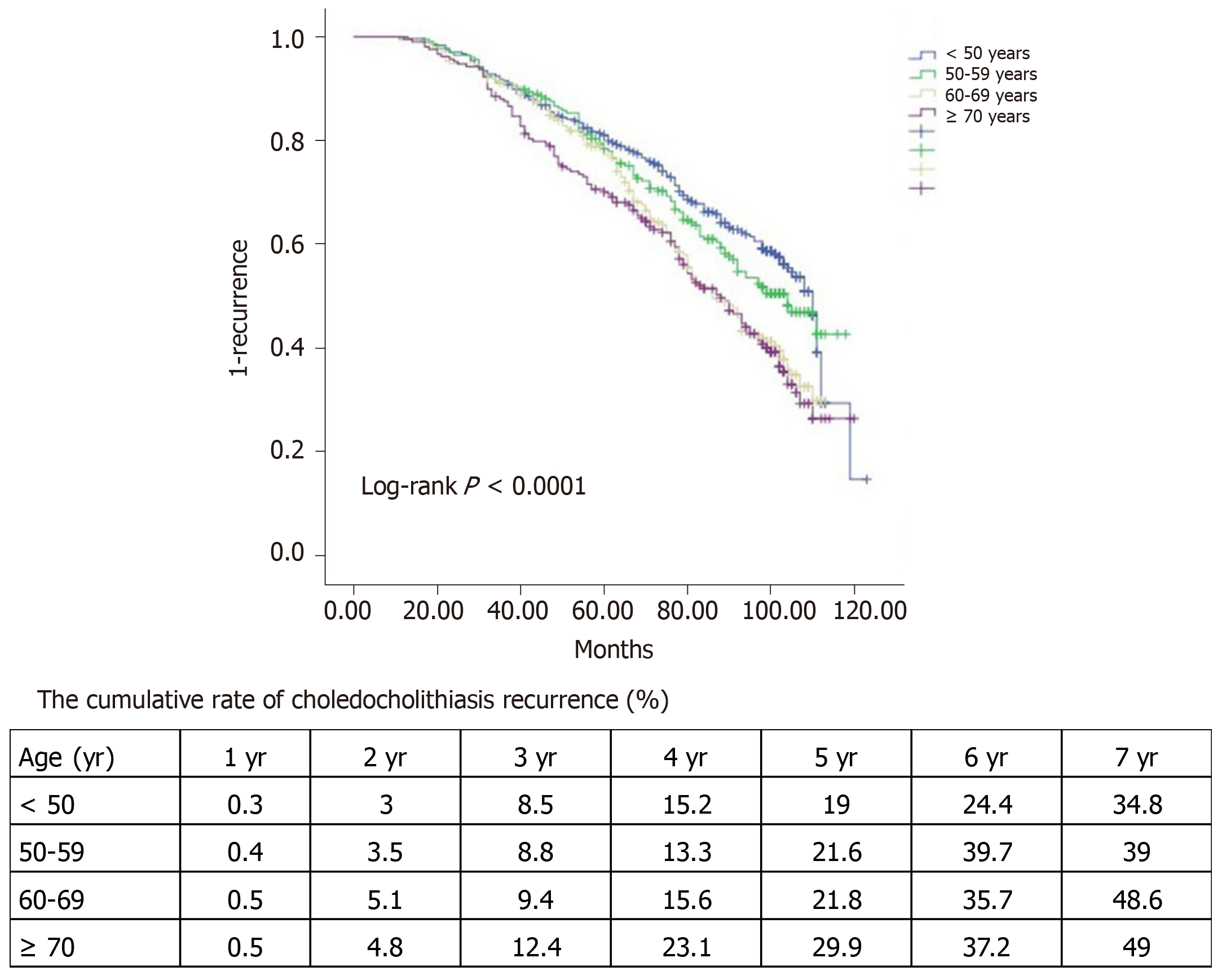

Multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis showed that age > 65 years (OR = 1.556, 95%CI: 1.079-2.244; P = 0.018), history of choledocholithotomy (OR = 2.474, 95%CI: 1.417-4.320; P = 0.001), EPBD (OR = 5.545, 95%CI: 3.026-10.162; P = 0.000), EST (OR = 3.378, 95%CI: 1.968-5.797; P = 0.000), CBD stent implantation (OR = 5.562, 95%CI: 3.326-9.301; P = 0.000), multiple ERCP procedures (OR = 3.601, 95%CI: 1.778-3.805; P = 0.000), stones in the intrahepatic bile duct (OR = 2.359, 95%CI: 1.516-3.668; P = 0.000), PAD (OR = 1.579, 95%CI: 1.090-2.289; P = 0.016), choledocholithiasis diameter ≥ 10 mm (OR = 1.599, 95%CI: 1.117-2.290; P = 0.010), biliary-duodenal fistula (OR = 2.720, 95%CI: 1.094-6.765; P = 0.031), no use of preoperative antibiotics (OR = 0.527, 95%CI: 0.346-0.801; P = 0.003), and biliary tract infections (OR = 1.059, 95%CI: 1.021-1.099; P = 0.003) were independent risk factors for the recurrence of choledocholithiasis after ERCP (Table 6). A Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that as age increased, the rate of choledocholithiasis recurrence increased proportionally (Figure 1).

| Variable | OR (95%CI) | P-value |

| Age > 65 yr | 1.556 (1.079-2.244) | 0.018 |

| Choledocholithotomy | 2.474 (1.417-4.320) | 0.001 |

| EPBD | 5.545 (3.026-10.162) | 0.000 |

| EST | 3.378 (1.968-5.797) | 0.000 |

| CBD stent implantation | 5.562 (3.326-9.301) | 0.000 |

| ERCP procedures | 2.601 (1.778-3.805) | 0.000 |

| Stones in the intrahepatic bile duct | 2.359 (1.516-3.668) | 0.000 |

| PAD | 1.579 (1.090-2.289) | 0.016 |

| Choledocholithiasis diameter ≥ 10 mm | 1.435 (1.094-1.883) | 0.009 |

| Biliary-duodenal fistula | 2.720 (1.094-6.765) | 0.031 |

| Used antibiotics before ERCP | 0.527 (0.346-0.801) | 0.003 |

| Biliary tract infections | 1.059 (1.021-1.099) | 0.003 |

The recurrence rate of choledocholithiasis after ERCP is reported to be 2%-22%[1-5]. In our studies, once choledocholithiasis recurred, the next recurrence rate increased in proportion to the number of instances of recurrence, as reported previously[1,10]. Several risk factors have been reported in various studies[1-3,6-8]. This study showed that age > 65 years, history of choledocholithotomy, EPBD, EST, CBD stent implantation, multiple ERCP procedures (≥ 2), stones in the intrahepatic bile duct, PAD, choledocholithiasis diameter ≥ 10 mm, bile duct-duodenal fistula, biliary tract infection, and no preoperative antibiotic use were independent risk factors for the recurrence of choledocholithiasis after ERCP.

It has been reported that the recurrence rate of choledocholithiasis in elderly patients (age > 65 years) can be as high as 30%[11]. The specific mechanism is unclear, but Keizman et al[4] believe that elderly patients have more risk factors for the recurrence of stones, such as CBD dilatation, CBD angulation, and PAD, which are related to the recurrence of stones. PAD is rare in patients younger than 40 years of age. It is found more often in older patients, and the occurrence of PAD increases with increasing age.

The surgical removal of choledocholithiasis, whether open or laparoscopic, is seldom performed and is usually reserved for patients in whom ERCP has failed[12]. Laparoscopic CBD exploration is considered in patients with larger stones in whom ERCP has failed. Stone recurrence caused by a history of choledocholithotomy may be due to long-term compression of the biliary tract by the T-tube placed during the choledocholithotomy leading to necrosis and scarring of the epithelial cells of the biliary tract, which easily cause biliary tract stenosis and disorders of biliary excretion[13].

Under physiological conditions, the sphincter of Oddi functions as a “switch” that controls the excretion of pancreatic juice and bile and prevents the reflux of intestinal fluid. Intraoperative ERCP surgeries, such as EPBD, EST, and multiple ERCP procedures, can cause dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi, which cannot be restored within a short period of time. Then, the barrier against intestinal fluid reflux weakens or disappears, and intestinal fluid can reflux into the bile duct. Because intestinal fluid contains a large amount of bacteria, digestive juices, and food residues, when it refluxes into the bile duct, it changes the bile duct loop and leads to bile duct infection[14]; the colonized bacteria produce β-glucuronic acid, which is associated with the formation of bilirubin calcium stones[5,6,15,16], thus promoting the recurrence of stones. Because bacterial contamination of the bile duct is a common finding in patients with choledocholithiasis, incomplete duct clearance may put patients at risk of cholangitis. Therefore, it is important for endoscopists to ensure that adequate biliary drainage is achieved in patients with choledocholithiasis that cannot be retrieved[17]. However, stents have been placed for long periods of time, leading to bile salt deposition and adherence to the stents. The stents can be a nidus for CBD stones. Bile duct stent placement affects biliary tract dynamics, predisposing the patient to cholestasis. On the one hand, siltation of bile is conducive to bacterial reproduction. On the other hand, concentration of bile stimulates inflammatory changes in the bile duct mucosa, resulting in the precipitation of bile bacteria, shedding cells, and inflammatory cells, which promote the recurrence of stones[18].

PAD form adjacent to the biliary and pancreatic duct confluence. When a diverticulum is large, it can directly compress the CBD, resulting in poor bile excretion. When a diverticulum is complicated by duodenal dysfunction, the food and refluxed intestinal fluid can remain in the diverticulum, stimulating long-term inflammation of the sphincter of Oddi, leading to dysfunction, duodenal papillary stenosis, and cholestasis[19]. PAD promotes the multiplication of beta-glucuronidase-producing bacteria, leading to earlier binding of dissociated glucuronide to bilirubin salts and promoting the pigmentation and formation of stones[20,21]. Larger stones often require lithotripsy, which may increase the risk of postoperative recurrence of stones. Larger stones cause greater forced expansion of the bile ducts and induce impaired function of normal bile ducts, leading to difficulties in bile excretion, which can easily cause cholestasis and bacterial infections[22,23]. Biliary tract infections mainly result from preoperative infections and retrograde reflux of intestinal fluid caused by reduced biliary pressure after cholecystectomy. Studies have shown that more than 94.6% of patients with pigmentary stones have positive bacterial cultures in their bile samples[24]. A variety of causes, such as abnormal biliary anatomy, PAD, abnormal biliary secretion, and biochemistry, can contribute to biliary tract infections. Bile duct bacteria is present, and the resulting beta-glucuronidase causes bilirubin hydrolysis to nonconjugated bilirubin, which can easily combine with calcium to form bilirubin calcium and promote gallstone formation[6,25-29]. The lack of preoperative use of antibiotics may increase the risk of biliary tract infections and promote the recurrence of stones. The presence of a biliary-duodenal fistula is a risk factor for the recurrence of choledocholithiasis. No relevant literature has been reported. Bile duct-duodenal fistulas often exist for a long time, and the refluxed intestinal fluid irritates the biliary mucosa, eventually leading to chronic inflammation.

This study was a single-center retrospective study. Although the clinical data of the patients were comprehensively analyzed and the risk factors for recurrence of choledocholithiasis after ERCP were studied in all aspects, there were still limitations to this retrospective study. This study did not further analyze the accuracy of individual risk factors for predicting the recurrence of choledocholithiasis. In conclusion, patient age greater than 65 years is an independent risk factor for the development of recurrent choledocholithiasis following ERCP, as is history of biliary surgeries, measures during ERCP, and prevention of postoperative complications.

Currently, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) technology is very advanced, but the recurrence of choledocholithiasis after ERCP is still a challenging problem. The potential causes of the recurrence of choledocholithiasis after ERCP are unclear.

To explore the independent risk factors for stone recurrence by comprehensively analyzing the relevant factors for stone recurrence in a large-sized sample.

The study aimed to analyze the potential causes of the recurrence of choledocholithiasis after ERCP.

The ERCP database of our medical center was retrospectively reviewed, and information regarding eligible patients was collected. A 1:1 case-control study was used for this investigation. Data were analyzed by univariate and multivariate logistic regression and Kaplan-Meier analyses.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that age > 65 years, combined history of choledocholithotomy, endoscopic papillary balloon dilation, endoscopic sphincterotomy, common bile duct stent implantation, multiple ERCP procedures (≥2), stones in the intrahepatic bile duct, periampullary diverticula, choledocholithiasis diameter ≥ 10 mm, bile duct-duodenal fistula, combined biliary tract infections, and no preoperative antibiotic use were independent risk factors for the recurrence of choledocholithiasis after ERCP.

In this large sample sized retrospective study, we concluded that patient age greater than 65 years is an independent risk factor for the development of recurrent choledocholithiasis following ERCP, as is history of biliary surgeries, measures during ERCP, and prevention of postoperative complications.

The pathogenesis of recurrence of choledocholithiasis should be studied in future, as well as the prevention and treatment.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fusaroli P, Gkekas I, Hara K S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Ando T, Tsuyuguchi T, Okugawa T, Saito M, Ishihara T, Yamaguchi T, Saisho H. Risk factors for recurrent bile duct stones after endoscopic papillotomy. Gut. 2003;52:116-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kim DI, Kim MH, Lee SK, Seo DW, Choi WB, Lee SS, Park HJ, Joo YH, Yoo KS, Kim HJ, Min YI. Risk factors for recurrence of primary bile duct stones after endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:42-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Risk factors predictive of late complications after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones: long-term (more than 10 years) follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2763-2767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Keizman D, Ish Shalom M, Konikoff FM. Recurrent symptomatic common bile duct stones after endoscopic stone extraction in elderly patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:60-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim KY, Han J, Kim HG, Kim BS, Jung JT, Kwon JG, Kim EY, Lee CH. Late Complications and Stone Recurrence Rates after Bile Duct Stone Removal by Endoscopic Sphincterotomy and Large Balloon Dilation are Similar to Those after Endoscopic Sphincterotomy Alone. Clin Endosc. 2013;46:637-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim KH, Rhu JH, Kim TN. Recurrence of bile duct stones after endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation combined with limited sphincterotomy: long-term follow-up study. Gut Liver. 2012;6:107-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim JH, Kim YS, Kim DK, Ha MS, Lee YJ, Lee JJ, Lee SJ, Won IS, Ku YS, Kim YS, Kim JH. Short-term Clinical Outcomes Based on Risk Factors of Recurrence after Removing Common Bile Duct Stones with Endoscopic Papillary Large Balloon Dilatation. Clin Endosc. 2011;44:123-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Song ME, Chung MJ, Lee DJ, Oh TG, Park JY, Bang S, Park SW, Song SY, Chung JB. Cholecystectomy for Prevention of Recurrence after Endoscopic Clearance of Bile Duct Stones in Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2016;57:132-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Strnad P, von Figura G, Gruss R, Jareis KM, Stiehl A, Kulaksiz H. Oblique bile duct predisposes to the recurrence of bile duct stones. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Park BK, Seo JH, Jeon HH, Choi JW, Won SY, Cho YS, Lee CK, Park H, Kim DW. A nationwide population-based study of common bile duct stone recurrence after endoscopic stone removal in Korea. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:670-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fritz E, Kirchgatterer A, Hubner D, Aschl G, Hinterreiter M, Stadler B, Knoflach P. ERCP is safe and effective in patients 80 years of age and older compared with younger patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:899-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Almadi MA, Barkun JS, Barkun AN. Management of suspected stones in the common bile duct. CMAJ. 2012;184:884-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yin Z, Xu K, Sun J, Zhang J, Xiao Z, Wang J, Niu H, Zhao Q, Lin S, Li Y. Is the end of the T-tube drainage era in laparoscopic choledochotomy for common bile duct stones is coming? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2013;257:54-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lu Y, Wu JC, Liu L, Bie LK, Gong B. Short-term and long-term outcomes after endoscopic sphincterotomy versus endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for bile duct stones. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:1367-1373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yasuda I, Fujita N, Maguchi H, Hasebe O, Igarashi Y, Murakami A, Mukai H, Fujii T, Yamao K, Maeshiro K, Tada T, Tsujino T, Komatsu Y. Long-term outcomes after endoscopic sphincterotomy versus endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1185-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Baek YH, Kim HJ, Park JH, Park DI, Cho YK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI. [Risk factors for recurrent bile duct stones after endoscopic clearance of common bile duct stones]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;54:36-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bergman JJ, Rauws EA, Tijssen JG, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Biliary endoprostheses in elderly patients with endoscopically irretrievable common bile duct stones: report on 117 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:195-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chopra KB, Peters RA, O'Toole PA, Williams SG, Gimson AE, Lombard MG, Westaby D. Randomised study of endoscopic biliary endoprosthesis versus duct clearance for bileduct stones in high-risk patients. Lancet. 1996;348:791-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee KM, Paik CN, Chung WC, Kim JD, Lee CR, Yang JM. Risk factors for cholecystectomy in patients with gallbladder stones after endoscopic clearance of common bile duct stones. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1713-1719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zoepf T, Zoepf DS, Arnold JC, Benz C, Riemann JF. The relationship between juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula and disorders of the biliopancreatic system: analysis of 350 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:56-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tzeng JJ, Lai KH, Peng NJ, Lo GH, Lin CK, Chan HH, Hsu PI, Cheng JS, Wang EM. Influence of juxtapapillary diverticulum on hepatic clearance in patients after endoscopic sphincterotomy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:772-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tsai TJ, Lai KH, Lin CK, Chan HH, Wang EM, Tsai WL, Cheng JS, Yu HC, Chen WC, Hsu PI. Role of endoscopic papillary balloon dilation in patients with recurrent bile duct stones after endoscopic sphincterotomy. J Chin Med Assoc. 2015;78:56-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mu H, Gao J, Kong Q, Jiang K, Wang C, Wang A, Zeng X, Li Y. Prognostic Factors and Postoperative Recurrence of Calculus Following Small-Incision Sphincterotomy with Papillary Balloon Dilation for the Treatment of Intractable Choledocholithiasis: A 72-Month Follow-Up Study. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2144-2149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Li X, Zhu K, Zhang L, Meng W, Zhou W, Zhu X, Li B. Periampullary diverticulum may be an important factor for the occurrence and recurrence of bile duct stones. World J Surg. 2012;36:2666-2669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cetta F. The role of bacteria in pigment gallstone disease. Ann Surg. 1991;213:315-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Seo DB, Bang BW, Jeong S, Lee DH, Park SG, Jeon YS, Lee JI, Lee JW. Does the bile duct angulation affect recurrence of choledocholithiasis? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4118-4123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Stewart L, Ponce R, Oesterle AL, Griffiss JM, Way LW. Pigment gallstone pathogenesis: slime production by biliary bacteria is more important than beta-glucuronidase production. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:547-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Leung JW, Liu YL, Leung PS, Chan RC, Inciardi JF, Cheng AF. Expression of bacterial beta-glucuronidase in human bile: an in vitro study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:346-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Begley M, Sleator RD, Gahan CG, Hill C. Contribution of three bile-associated loci, bsh, pva, and btlB, to gastrointestinal persistence and bile tolerance of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 2005;73:894-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |