Published online Mar 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i5.600

Peer-review started: October 31, 2018

First decision: December 12, 2018

Revised: December 20, 2018

Accepted: December 29, 2018

Article in press: December 30, 2018

Published online: March 6, 2019

Processing time: 126 Days and 18.5 Hours

As the first-line regimens for the treatment of advanced gastric cancer, both docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (DCF) and epirubicin, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (ECF) regimens are commonly used in clinical practice, but there is still controversy about which is better.

To compare the efficacy and safety of DCF and ECF regimens by conducting this meta-analysis.

Computer searches in PubMed, EMBASE, Ovid MEDLINE, Science Direct, Web of Science, The Cochrane Library and Scopus were performed to find the clinical studies of all comparisons between DCF and ECF regimens. We used progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), objective response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR), and adverse effects (AEs) as endpoints for analysis.

Our meta-analysis included seven qualified studies involving a total of 598 patients. The pooled hazard ratios between the DCF and ECF groups were comparable in PFS (95%CI: 0.58-1.46, P = 0.73), OS (95%CI: 0.65-1.10, P = 0.21), and total AEs (95%CI: 0.93-1.29, P = 0.30). The DCF group was significantly better than the ECF group in terms of ORR (95%CI: 1.13-1.75, P = 0.002) and DCR (95%CI: 1.03-1.41, P = 0.02). However, the incidence rate of grade 3-4 AEs was also greater in the DCF group than in the ECF group (95%CI: 1.16-1.88, P = 0.002), especially for neutropenia and febrile neutropenia.

With better ORR and DCR values, the DCF regimen seems to be more suitable for advanced gastric cancer than the ECF regimen. However, the higher rate of AEs in the DCF group still needs to be noticed.

Core tip: This study is the first meta-analysis to compare docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (DCF) and epirubicin, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (ECF) regimens for advanced gastric cancer. The results showed that progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and total adverse effects (AEs) between the DCF and ECF groups were comparable. The DCF group was significantly better in terms of ORR and DCR than the ECF group. However, the incidence rate of grade 3-4 AEs was also greater in the DCF group than in the ECF group, especially for neutropenia and febrile neutropenia. Therefore, DCF regimen seems to be more suitable for advanced gastric cancer than the ECF regimen.

- Citation: Li B, Chen L, Luo HL, Yi FM, Wei YP, Zhang WX. Docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil compared with epirubicin, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil regimen for advanced gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(5): 600-615

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i5/600.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i5.600

Gastric cancer has become the fifth most frequently diagnosed malignancy and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide[1-3]. Most patients are unable to get timely diagnosis and effective treatment due to the lack of obvious symptoms in the early stage. Moreover, many patients are likely to relapse even after regular radiotherapy and chemotherapy[4]. Gastric cancer is sensitive to chemotherapy, and it is more clinically treated with combined chemotherapy for the purpose of palliative treatment[5,6].

Many regimens have been used for the treatment of patients with advanced gastric cancer, but none are considered standard. Recommended by clinical guidelines, docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (DCF) and epirubicin, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (ECF) regimens are commonly used as first-line treatments for gastric cancer[7]. The results in some studies showed that the DCF group was better than the ECF group in terms of objective response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS)[8-9]. However, in other studies, opposite results were obtained, and the ECF regimen had better antitumor efficacy and better quality of life for advanced gastric cancer[10,11]. In a retrospective analysis from Turkey, Teker et al reported that DCF and ECF had similar efficacy and tolerability in treating advanced gastric cancer[12].

To solve the controversy, we conducted this meta-analysis of relevant studies to compare the survival outcomes [PFS, OS, ORR, and disease control rate (DCR)] and adverse effects (AEs) between DCF and ECF regimens.

This meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis guidelines[13].

A systematic literature search of PubMed, EMBASE, Ovid Medline, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, The Cochrane Library and Scopus was performed up to August 31, 2018, combining the following mesh terms: “gastric cancer", “epirubicin", "docetaxel”, and "chemotherapy”. Our complete search for PubMed was: [docetaxel (Mesh Terms) OR docetaxel hydrate OR docetaxel trihydrate OR docetaxel anhydrous] AND [epirubicin (Mesh Terms) OR 4'-epidoxorubicin OR EPI-cell OR IMI28 OR NSC 256942 OR NSC256942 OR Ellence] AND [stomach neoplasm (Mesh Terms) OR gastric cancer OR stomach cancer OR stomach neoplasm OR gastric neoplasm OR cancers of stomach]. Search results were limited to original human studies, and search criteria were restricted to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or cohort studies without language restriction. The search is supplemented by manually searching for references listed in all included studies.

We used the following criteria for selecting studies: (1) Population: Patients diagnosed with metastatic or advanced gastric cancer; (2) Intervention and comparison: DCF vs ECF; (3) Outcomes: PFS, OS, ORR, DCR, and AEs; and (4) Study design: High-quality RCTs and cohort studies. Studies without primary data, abstracts only, conference summary, meta-analysis, animal experiments, and duplicate data were excluded.

Data were independently extracted by two reviewers, including the following: (1) first author, year, dosage regimen, dosage and cycle, patient characteristics, and study design; (2) PFS, OS, ORR, and DCR; and (3) AEs (all-grade/grade 3-4). A third investigator resolved any disagreements about terms.

The Jadad scale (5-point)[14] and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS, 9-point)[15] were used to assess the methodological quality of RCTs and cohort studies, receptively. Three main items were included in the Jadad scale: Randomization, masking, and accountability of all patients. The NOS also included three main items: Patient selection, comparability, and exposure. The scores were allocated as stars to each study. RCTs achieving three or more stars were considered to be of high quality. Cohort studies achieving eight to nine stars were considered to be of high quality; six to seven stars were considered to be of medium quality.

Meta-analysis was performed with RevMan (Version 5.3) and STATA (Version 12.0). PFS and OS were analyzed by the pooled hazard ratio (HR); if the HR was less than 1, the result favored the DCF group; otherwise, it favored the ECF group. ORR, DCR, and AEs were analyzed by the pooled risk ratio. We extracted the HR of PFS and OS directly from studies or from Kaplan–Meier curves according to Tierney et al[16]. The heterogeneity test was evaluated by using the Q test and I2 statistic. If P > 0.1 and I2 < 50%, the fixed effects model was used. Otherwise, the random effects model was used[17]. Begg’s and Egger’s tests were performed to assess possible publication bias. The result was considered statistically significant if the P-value was less than 0.05.

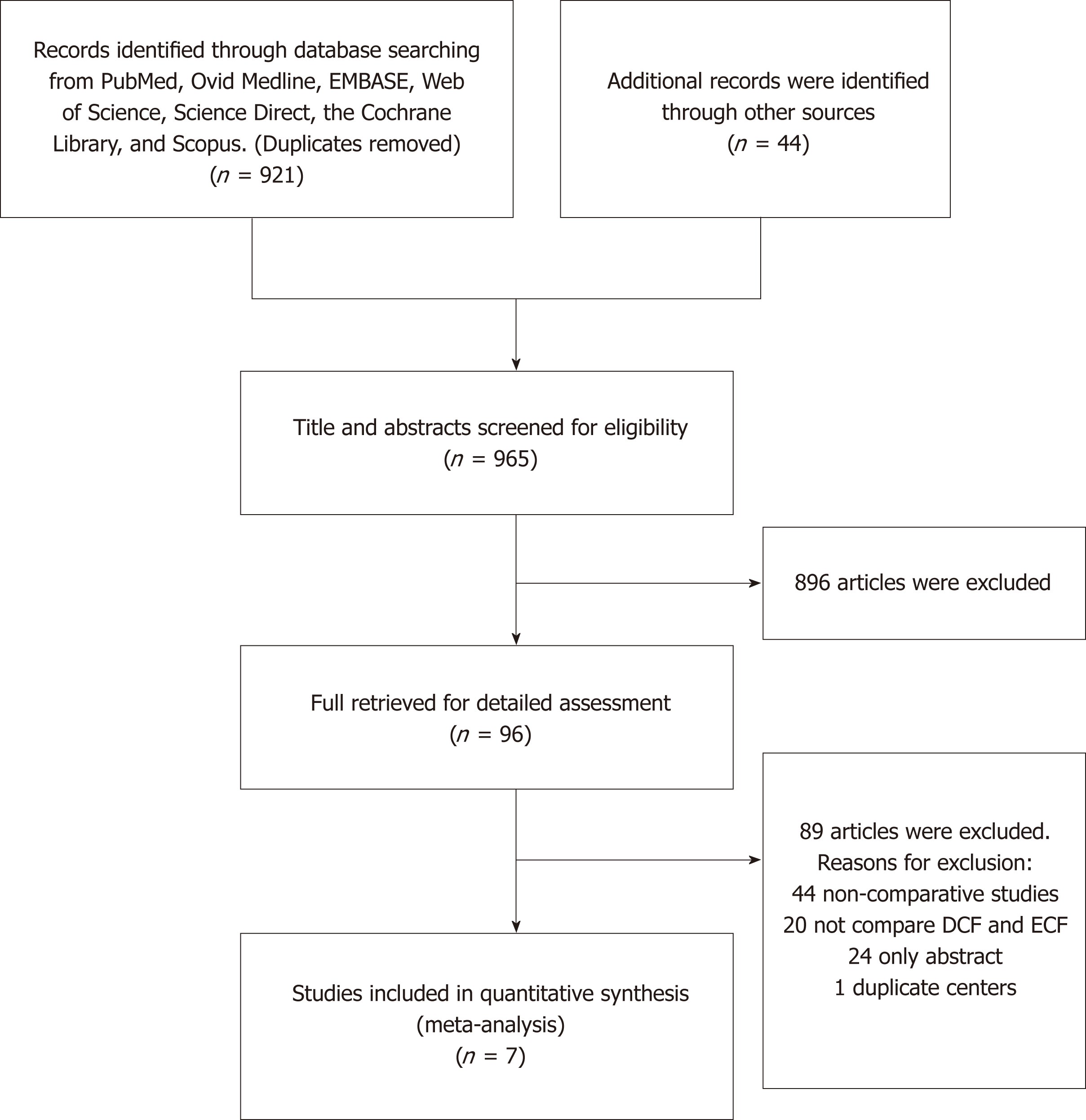

We initially identified 965 potentially eligible studies. We further deleted the poor quality and repeated studies and ultimately included seven qualified studies (four RCTs and three cohort studies). A total of 598 cases of metastatic or advanced gastric cancer were included (257 patients in the DCF group and 341 patients in the ECF group). According to the Jadad scale and NOS, five studies were of high quality (four RCTs and one cohort study), and two cohort studies were of medium quality (Table 1). The selection procedure is shown in Figure 1, and the characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 2.

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Exposure | Randomization | Masking | Accountability of all patients | Quality (score) |

| Randomized controlled trial | |||||||

| Sadighi et al[18], 2006 | ** | ** | * | 5 | |||

| Roth et al[10], 2007 | ** | * | * | 4 | |||

| Gao et al[11], 2010 | ** | ** | * | 5 | |||

| Babu et al[9], 2017 | * | * | * | 3 | |||

| Retrospective study | |||||||

| Abbasi et al[19], 2010 | *** | ** | * | 6 | |||

| Kilickap et al[8], 2011 | *** | ** | ** | 7 | |||

| Teker et al[12], 2014 | **** | ** | *** | 9 | |||

| Ref. | Yr | Intervention and control | Samples | ORR (%) | OS | PFS | Design | Quality (score) |

| Sadighi et al[18] | 2006 | DCF: D 60 mg/m2, d1, C 60 mg/m2, d1, F 750 mg/m2/d, d1-5 (21) | 44 | 42.0 | - | - | RCT | 5/5 |

| ECF: E 60mg/m2, d1, C 60 mg/m2, d1, F 750 mg/m2/d, d1-5 (21) | 42 | 37.0 | - | - | ||||

| Roth et al[10] | 2007 | DCF: D 85mg/m2, d1, C 75 mg/m2, d1, F 300 mg/m2/d, d1-14 (21) | 41 | 36.6 | 10.4 | 4.6 | RCT | 4/5 |

| ECF: E 50 mg/m2, d1, C 60 mg/m2, d1, F 200 mg/m2/d, d1-21 (21) | 40 | 25.0 | 8.3 | 4.9 | ||||

| Abbasi et al[19] | 2010 | DCF: D 75mg/m2, d1, C 75 mg/m2, d1, F 750 mg/m2/d, d1-5 (21) | 30 | 56.3 | 10.81 | 6.81 | RS | 6/9 |

| ECF: E 50 mg/m2, d1, C 60 mg/m2, d1, F 200 mg/m2/d, d1-21 (21) | 113 | 31.3 | 8.06 | 5.13 | ||||

| Gao et al[11] | 2010 | DCF: D 60 mg/m2, d1, C 25 mg/m2, d1-3, F 1000 mg/m2, 46 h, pumping (21) | 32 | 59.3 | - | - | RCT | 5/5 |

| ECF: E 50 mg/m2, d1, C 25 mg/m2, d1-3, F 1000 mg/m2, 46 h, pumping (21) | 32 | 32.6 | - | - | ||||

| Kilickap et al[8] | 2011 | DCF: D 75 mg/m2, d1, C 75 mg/m2, d1, F 750 mg/m2/d, d1-5 (21) | 40 | 40.0 | 9.6 | 5.8 | RS | 7/9 |

| ECF: E 50 mg/m2, d1, C 60 mg/m2, d1, F 250 mg/m2/d, d1-21 (21) | 40 | 30.0 | 10.1 | 4.4 | ||||

| Teker et al[12] | 2014 | DCF: D 50-75 mg/m2, d1, C 50-75 mg/m2, d1, F 500-750 mg/m2/d, d1-5 (21) | 42 | 26.2 | 11 | 6.0 | RS | 9/9 |

| ECF: E 50 mg/m2, d1, C 60 mg/m2, d1, F 200 mg/m2/d, d1-21 (21) | 44 | 29.5 | 10 | 6.0 | ||||

| Babu et al[9] | 2017 | DCF: D 75 mg/m2, d1, C 60 mg/m2, d1, F 750 mg/m2/d, d1-5 (21) | 28 | 46.4 | 12.5 | 7.5 | RCT | 3/5 |

| ECF: E 50 mg/m2, d1, C 60 mg/m2, d1, F 750 mg/m2/d, d1-5 (21) | 30 | 26.7 | 9.4 | 5.8 |

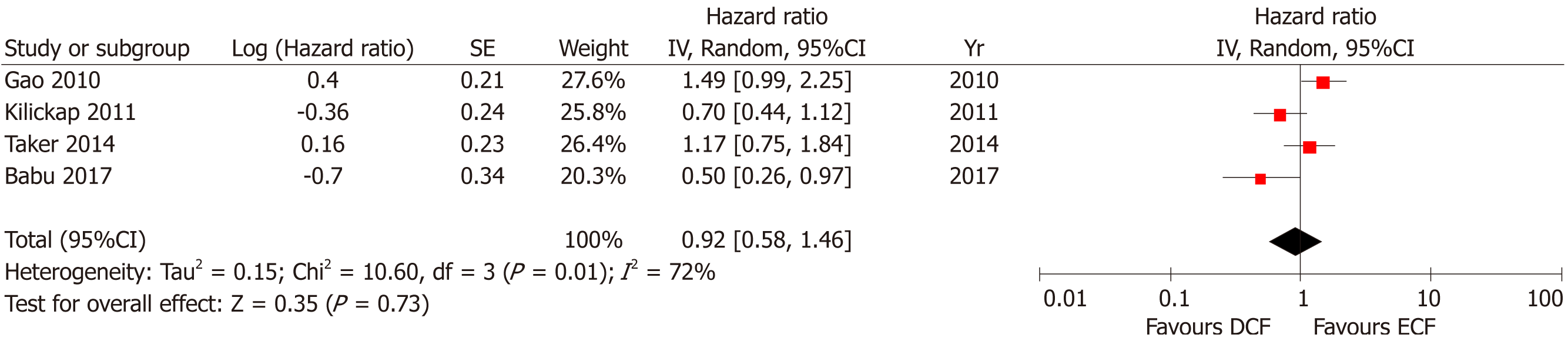

Four studies including 288 patients reported PFS. No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups (95%CI: 0.58-1.46, P = 0.73), with significant heterogeneity (P = 0.01; I2 = 72%, Figure 2).

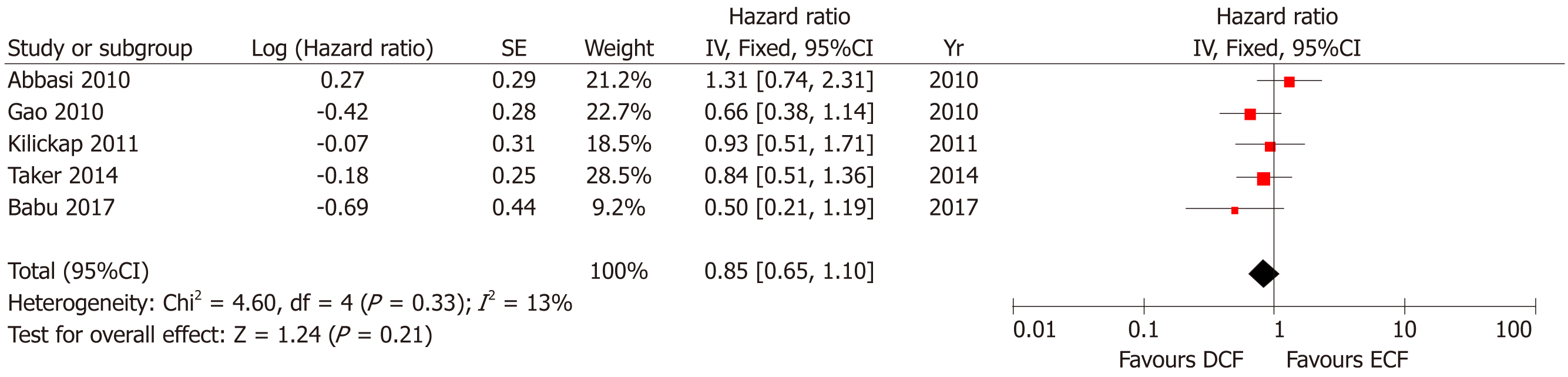

Five studies including 431 patients reported OS. No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups (95%CI: 0.65-1.10, P = 0.21), with acceptable heterogeneity (P = 0.33; I2 = 13%, Figure 3).

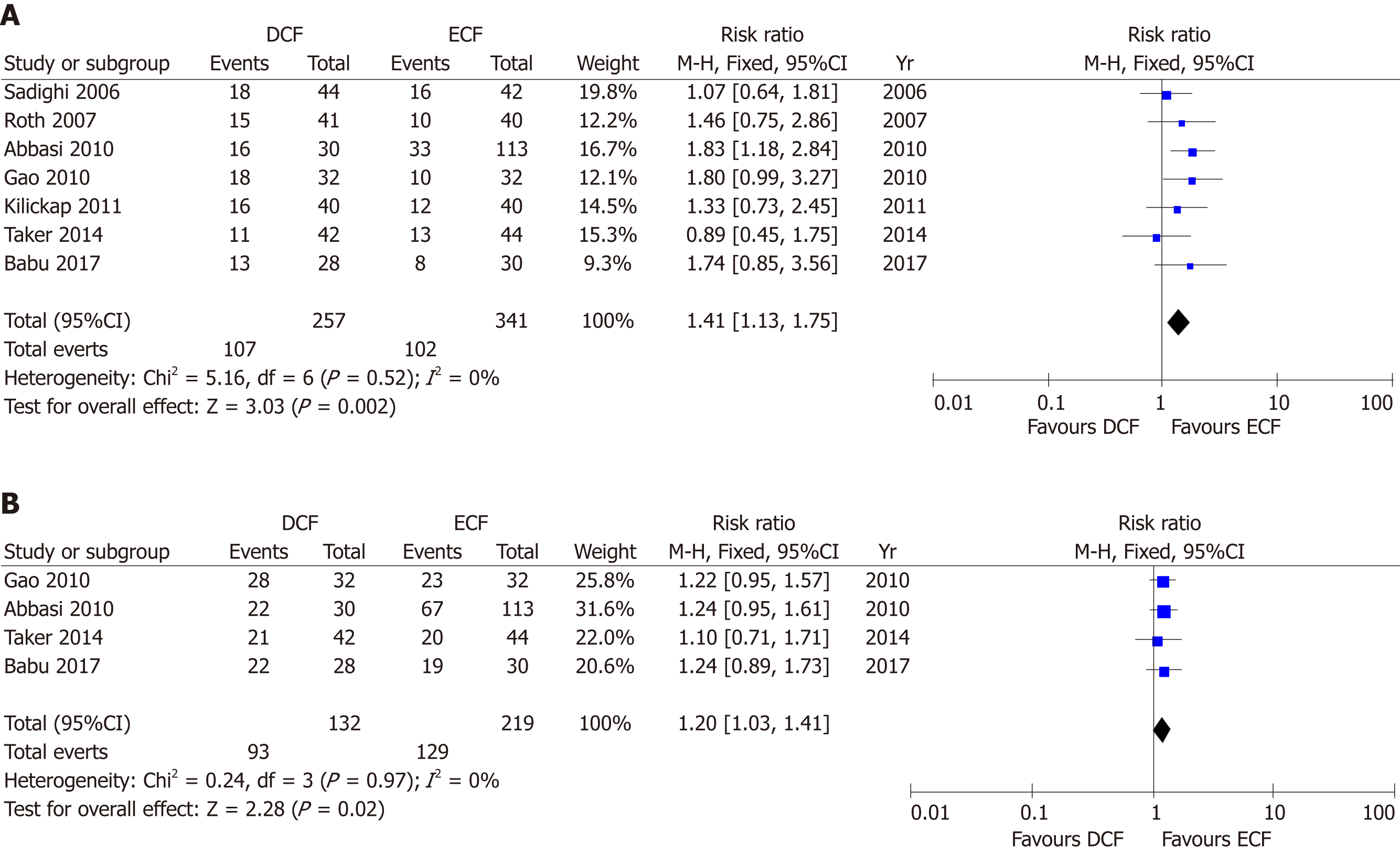

Seven studies including 598 patients reported ORR. ORR was significantly greater in the DCF group than in the ECF group (95%CI: 1.13-1.75, P = 0.002), with no heterogeneity (P = 0.52; I2 = 0%, Figure 4A).

Four studies including 351 patients reported DCR. DCR was significantly greater in the DCF group than in the ECF group (95%CI: 1.03-1.41, P = 0.02), with no heterogeneity (P = 0.97; I2= 0%, Figure 4B).

We evaluated toxicities between the DCF and ECF groups based on total AEs (all-grade/grade 3-4). In subgroup analysis, we also evaluated the top ten reported AEs (all-grade/grade 3-4).

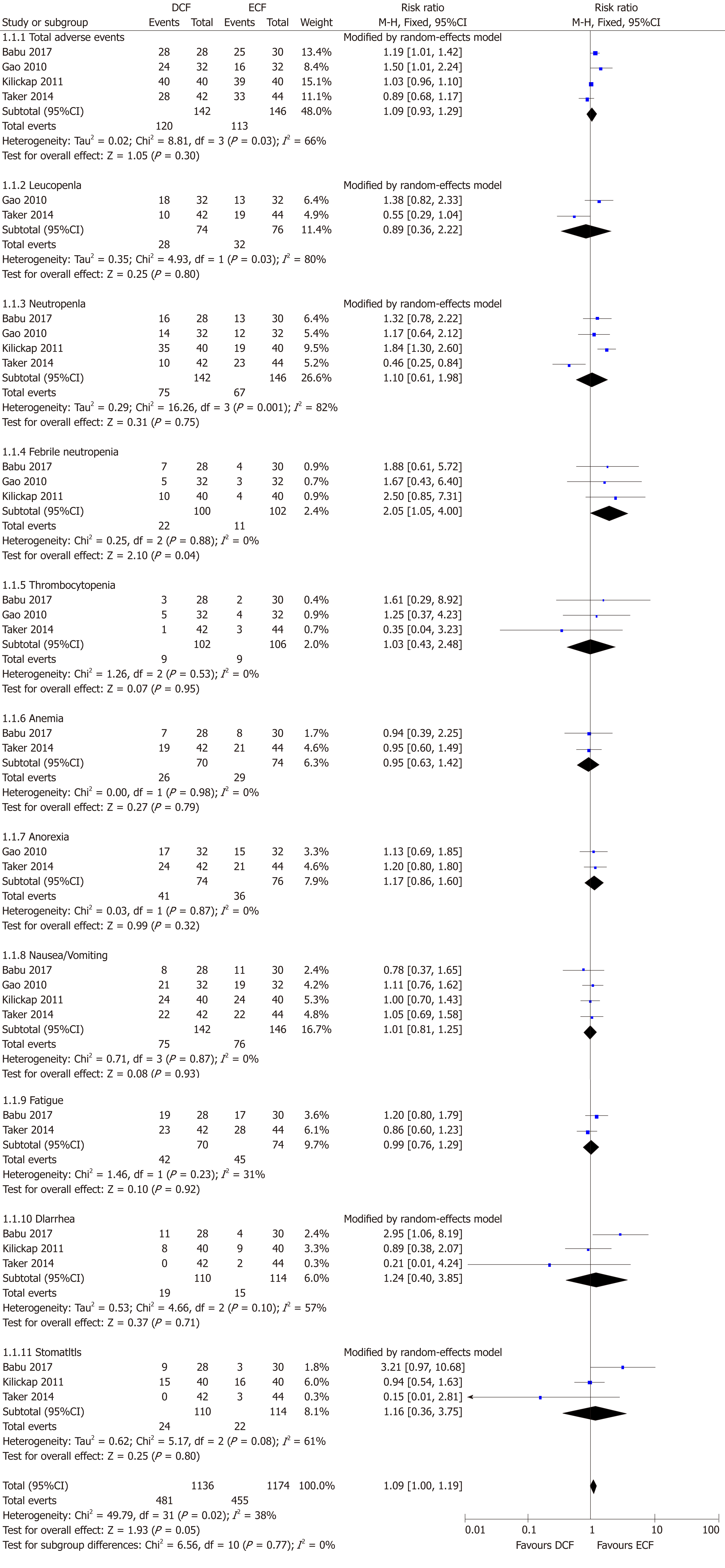

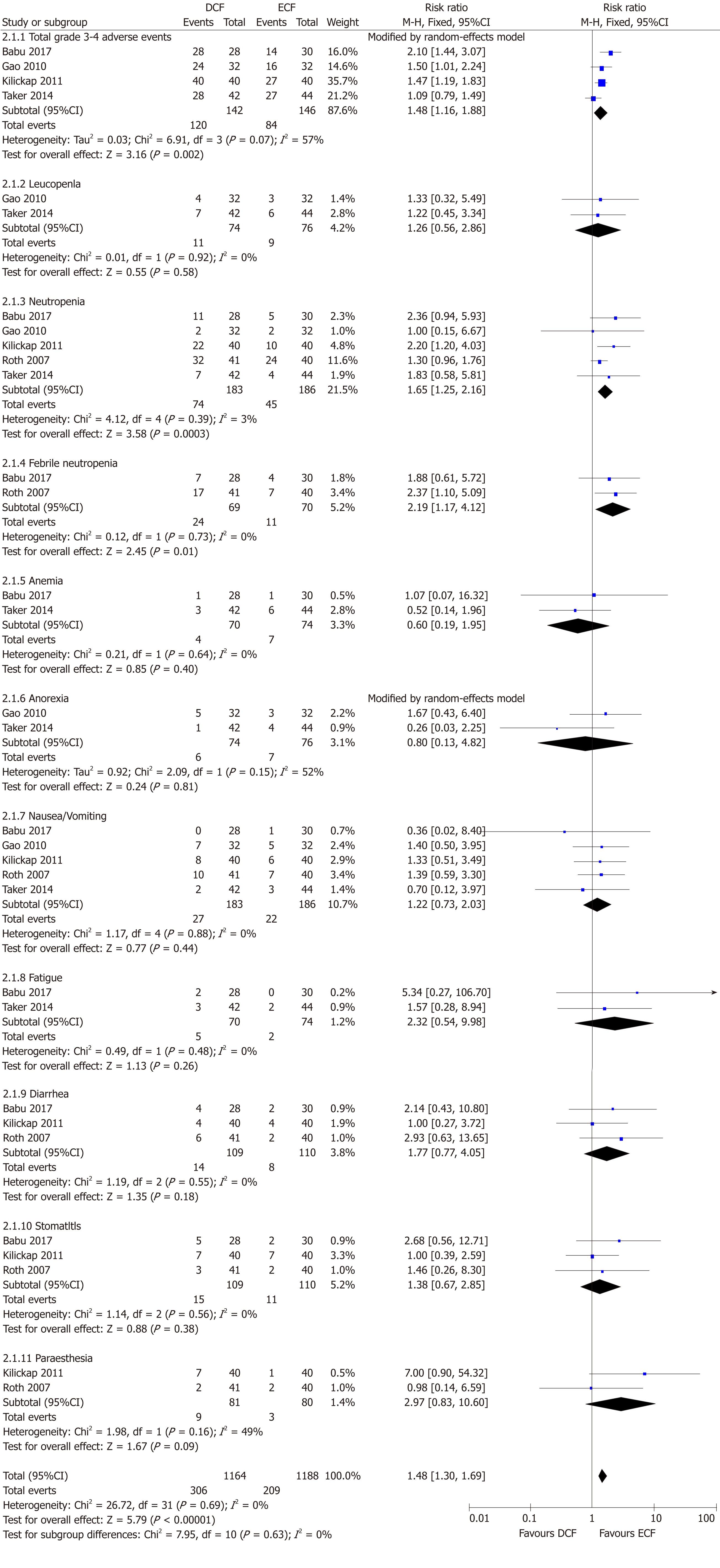

Four studies including 288 patients reported total all-grade AEs. No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups (95%CI: 0.93-1.29, P = 0.30), with significant heterogeneity (P = 0.03; I2 = 66%, Figure 5). In the subgroup analysis, DCF induced a significantly greater rate of febrile neutropenia than ECF (95%CI: 1.05-4.00, P = 0.04). Similar incidence rates of leucopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, anorexia, nausea/vomiting, fatigue, diarrhea, and stomatitis were found between the two groups.

Four studies including 288 patients reported total grade 3-4 AEs. The incidence rate of grade 3-4 AEs was significantly greater in the DCF group than in the ECF group (95%CI: 1.16-1.88, P = 0.002), with significant heterogeneity (P = 0.07; I2 = 57%, Figure 6). In the subgroup analysis, compared to ECF, DCF induced a significantly greater rate of neutropenia (95%CI: 1.25-2.16, P = 0.0003) and febrile neutropenia (95%CI: 1.17-4.12, P = 0.01). Similar incidence rates of leucopenia, anemia, anorexia, nausea/vomiting, fatigue, diarrhea, stomatitis, and paraesthesia were found between the two groups.

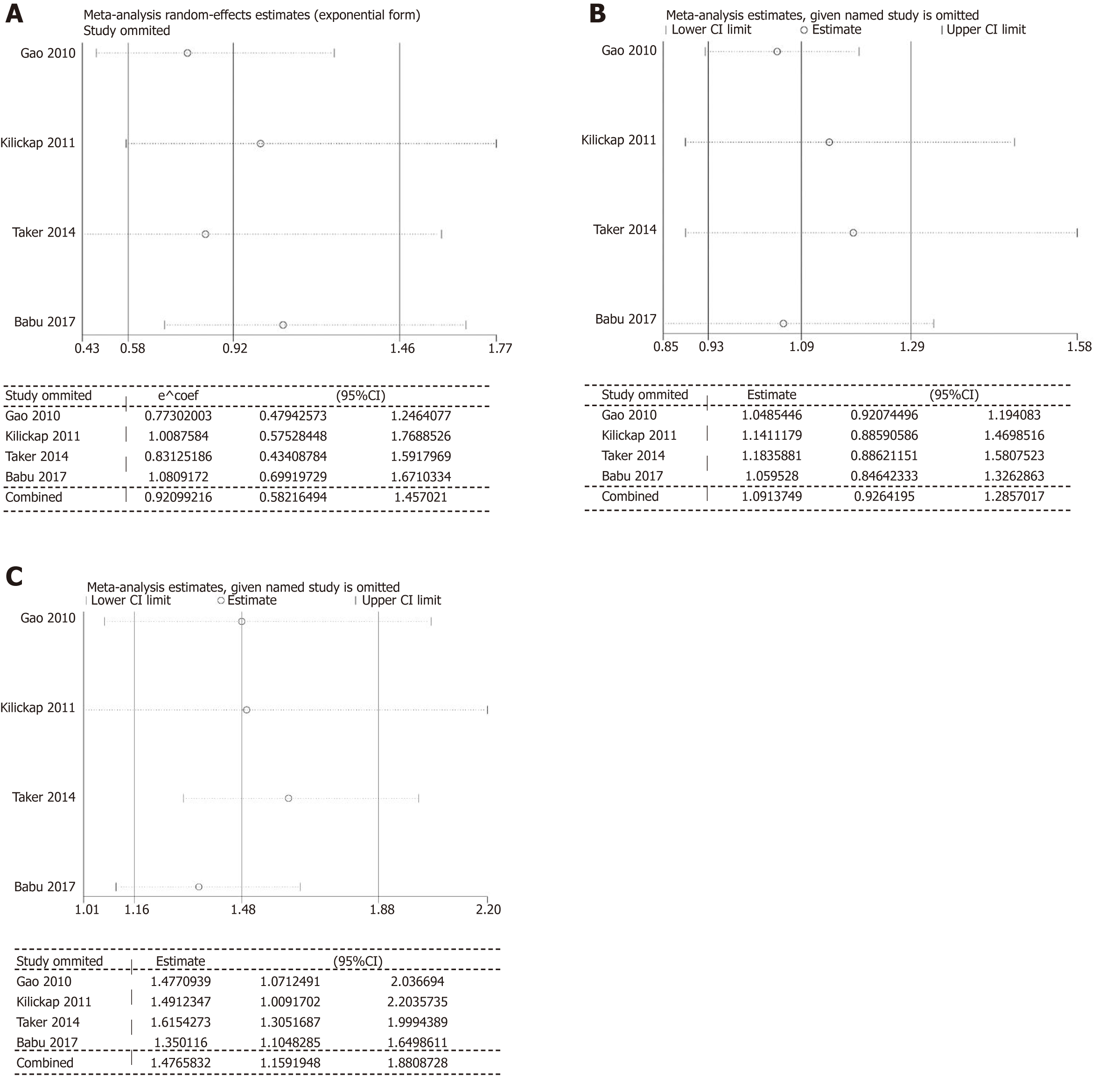

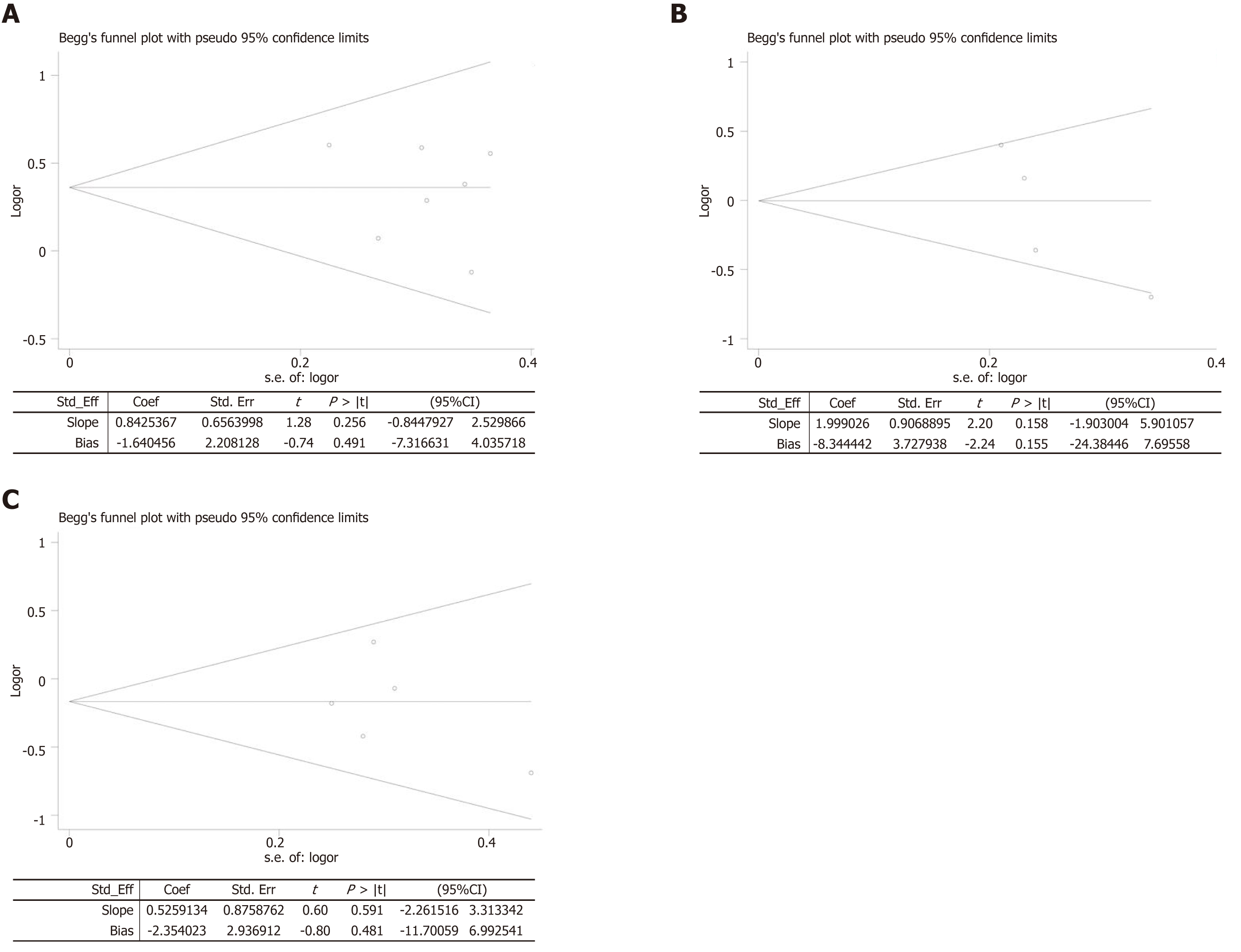

In the analysis of PFS and total AEs (all-grade/grade 3-4), our results showed significant heterogeneity. We excluded a single study to evaluate the impact of the study on the pooled results. The results suggested that the outcomes of PFS, all-grade AEs, and grade 3-4 AEs were stable and reliable (Figure 7). The results of Begg’s test and Egger’s tests were as follows: ORR (P = 0.548; P = 0.491, Figure 8A), PFS (P = 0.089; P = 0.155, Figure 8B), and OS (P = 0.806; P = 0.481, Figure 8C). There was no evidence to identify significant publication bias.

Gastric cancer is still a worldwide malignant tumor with a high mortality rate[20]. At present, since screening gastric cancer is difficult to popularize, most patients are in an advanced stage and have lost the chance of radical operation when diagnosed[21]. Even if the tumors can be excised, there is a great chance of local recurrence after the operation[22]. Cisplatin-based combinations [particularly cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (CF)] have been recognized as one of the preferred regimens for advanced gastric cancer. As improved regimens, both DCF and ECF regimens are superior to CF[23,24]. This study is the first meta-analysis to compare DCF and ECF regimens for advanced gastric cancer. The results showed that PFS, OS, and total AEs between the DCF and ECF groups were comparable. The DCF group was significantly better in terms of ORR and DCR than the ECF group. However, the incidence rate of grade 3-4 AEs was also greater in the DCF group than in the ECF group, especially for neutropenia and febrile neutropenia.

From our results, four studies[9,10,12,19] showed that DCF significantly prolonged the OS of patients compared with ECF, and three studies[8,9,19] showed that DCF significantly prolonged the PFS of patients compared with ECF. The results were beneficial to the translation of OS and PFS from the DCF regimen to the pooled median survival time of approximately 1 mo. However, no significant difference was found in OS or PFS between the two groups. Compared to non-docetaxel-containing regimens, Wagner et al[25] found that the results in OS and PFS might be extended slightly or without any difference[25]. Furthermore, the advantages of trivalent regimens containing docetaxel (DCF and FLO-T) might be offset by increased toxicity. Although our results did not show significant differences, it was possible that both regimens were effective in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer, probably because of the small number of cases. We looked forward to a larger scale of related research.

Our results showed an advantage in the improvement of ORR and DCR in the DCF group. Only one study[12] showed that the ORR of the DCF group was lower than that of the ECF group (26.2% vs 29.5%, respectively). These results might be because docetaxel had better efficacy, and the patient's response to this drug was relatively high. Its curative effect is largely related to its mechanism of action. Docetaxel is a taxane compound discovered in the 1990s. It mainly enhances tubulin aggregation and inhibits microtubule depolymerization, leading to the formation of stable non-functional microtubule bundles, thus destroying the mitosis of cancer cells to achieve anti-tumor effects. Compared with paclitaxel, it has stronger activity and broader anti-tumor spectrum. Epirubicin is an antibiotic anti-tumor drug, which belongs to a non-specific cell cycle anti-cancer drug. Its mechanism is to directly insert DNA nucleotide pairs to interfere with the transcription process and prevent the synthesis of RNA and DNA. Similar to our results, Petrioli et al[26] reported that docetaxel-based regimens showed an increase in ORR compared with epirubicin-based regimens; however, no significant difference was found between the two groups[26]. A meta-analysis of DCF compared with non-docetaxel-containing regimens analyzed 12 RCTs for a total of 1089 cases with advanced gastric cancer. The results did not show any significant difference in CR or SD rates, but the DCF regimen can significantly increase the PR rate (38.8% vs 27.9%, respectively; 95%CI 1.16-1.65, P = 0.0003) compared with other regimens[27]. In four studies comparing docetaxel and non-docetaxel-containing regimens involving 1235 participants[24,28-30], the pooled ORRs were 43% and 30%, respectively (95%CI: 1.45-2.32, P = 0.002). In addition, due to higher response rates, individuals with good performance might have greater advantages from the three drug regimens, especially those containing docetaxel[25].

With respect to toxicity, hematological toxicity was confirmed to be the most common adverse event associated with the DCF regimen. In our analysis, we found high incidences of neutropenia and febrile neutropenia in the DCF group. Although it did not affect the efficacy of drugs, it might cause damage to other organs[31]. In recent years, many institutions have designed a number of improvements to regimens, such as DC or DF, capecitabine and oxaliplatin instead of 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin, or have changed the method of administration to weekly administration. Preliminary results showed that the AEs of the improved regimens were significantly lower than those of the DCF regimen, and the survival time seemed to be prolonged, but no significant difference was found in efficacy[32-33]. Based on the national comprehensive cancer network guidelines, DCF and ECF are considered high-risk and intermediate-risk regimens, respectively, for febrile neutropenia[7]. Phase I and phase II clinical studies have shown that docetaxel-induced toxicity is better tolerated when used weekly. The frequency of myelosuppression associated with neutropenia can also be reduced with weekly administration[34-37]. The AEs of DCF are acceptable only with appropriately selected patients and comprehensive toxicity management strategies. It is interesting to note that after appropriate dose reduction, the rates of neutropenia and febrile neutropenia were reduced with DCF. European and North American guidelines recommend the routine use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) prophylaxis when using chemotherapy regimens associated with a risk of neutropenia and febrile neutropenia[36,37]. Many studies have shown that G-CSF can control these two toxicities[38,39]. In this meta-analysis, we can see that the toxicity and side effects of the DCF regimen were relatively large, but with the improvement of medical level, the adverse reactions can be controlled and prevented. However, the combination of the three drugs should be carefully considered for the elderly and poor physique patients. Therefore, appropriate preventive measures should be taken in advance for patients who cannot tolerate the related toxicity.

In addition, we should note that there are still some limitations in this meta-analysis: (1) not all of the studies are RCTs; (2) the total number of analyzed patients is small, which may not reflect the whole population; (3) significant heterogeneity existed in some comparisons; (4) some studies did not provide the data we have analyzed; (5) the number of AEs may not completely reflect the quality of life; and (6) the doses of anticancer agents were different in each study, which might increase heterogeneity between the included studies.

In conclusion, Both DCF and ECF are effective regimens for advanced gastric cancer, with comparable PFS, OS, and total AEs. The DCF regimen has greater advantages over the ECF regimen in terms of ORR and DCR. However, the incidence rate of grade 3-4 AEs is also higher in the DCF group. Due to the inherent limitations of the study, more large-scale and high-quality RCTs are needed to support this conclusion.

Gastric cancer has always been a disease with high morbidity and mortality in the world. Because of the lack of obvious symptoms and signs in the early stage, many patients are found to have been diagnosed in the advanced stage. At the same time, none of the first-line treatments for advanced gastric cancer is standard. At present, docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (DCF) and epirubicin, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (ECF) are both effective first-line regimens for clinical use, but in many countries, different researchers have different opinions. There are still many disputes about the advantages and disadvantages of these two regimens. The results in some studies showed that the DCF group was better than the ECF group. However, in other studies, opposite results were obtained. To solve the controversy, we conducted this meta-analysis.

In many studies, both DCF and ECF regimens have shown good outcomes, but on the other hand, they also show many disadvantages, especially in the adverse effects (AEs). Since there is still much controversy in this field, and there is lack of evidence of evidence-based medicine in relevant fields to prove that which regimen is more suitable for clinical use, it is necessary to conduct relevant meta-analysis. This study therefore aimed to provide a more focused analysis through the evaluation of the survival outcomes and AEs between DCF and ECF regimens.

Our primary objective was to analyze the efficacy of the two first-line regimens in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer by obtaining the best and latest data from clinical trials. In the discussion section, we cited many frontier studies in related fields, and focused on the analysis of the reasons for the difference in therapeutic effect between DCF and ECF regimens. At the same time, we also hope that our research can play a guiding and helpful role in clinical medication.

We conducted this meta-analysis according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis guidelines. Seven main databases were searched up to August 31, 2018. Search results were limited to original human studies, and search criteria were restricted to randomized controlled trials or cohort studies without language restriction. We selected studies according to the PICOS principle. The Jadad scale and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale were used to assess quality of the studies, and RevMan and STATA were used to analyze the data. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were analyzed by the pooled hazard ratio. Objective response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR), and AEs were analyzed by the pooled risk ratio. The heterogeneity test was evaluated by using the Q test and I2 statistic. If P > 0.1 and I2 < 50%, the fixed effects model was used. Otherwise, the random effects model was used.

Our meta-analysis included seven high quality articles and 598 patients with advanced gastric cancer for the final analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of the DCF regimen and ECF regimen. The results showed that DCF and ECF were both effective with comparable PFS (95%CI: 0.58-1.46, P = 0.73) and OS (95%CI: 0.65-1.10, P = 0.21). The DCF group showed significantly better ORR (95%CI: 1.13-1.75, P = 0.002) and DCR (95%CI: 1.03-1.41, P = 0.02) than the ECF group. We evaluated toxicities between the DCF and ECF groups based on total (all-grade/grade 3-4) AEs. The AEs between the two groups were only significantly different in the aspects of neutropenia (95%CI: 1.25-2.16, P = 0.0003) and febrile neutropenia (95%CI: 1.17-4.12, P = 0.01), while other toxicities showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups.

This study is the latest meta-analysis to compare DCF and ECF regimens for advanced gastric cancer. From this result, we conclude that DCF regimen seems to be more suitable for advanced gastric cancer than the ECF regimen. This finding is extremely important for the research and guidance of clinical medication in related fields. DCF regimen, like most drugs, is not perfect and in some respects shows some unsatisfactory aspects. We cannot deny the effectiveness of DCF in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer, but we cannot ignore its side effects.

Our evidence of evidence-based medicine is mainly based on the original clinical research, but at present it seems that the research in related fields is still very deficient, which directly leads to the great limitation of our access to clinical evidence. Although there is still much controversy about the first-line drug use in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer, because gastric cancer cells are relatively sensitive to chemotherapeutic drugs, it is expected that larger clinical trials in the future can be conducted for related research.

The authors thank Professor Ji-Chun Liu, MD, PhD (Department of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University) and Professor Xiao-Shu Cheng, MD, PhD (Department of Cardiology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University) for their advice.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Crumley ABC, Kimura A S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 55842] [Article Influence: 7977.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (132)] |

| 2. | Wagner AD, Wedding U. Advances in the pharmacological treatment of gastro-oesophageal cancer. Drugs Aging. 2009;26:627-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ang TL, Fock KM. Clinical epidemiology of gastric cancer. Singapore Med J. 2014;55:621-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Das P, Ajani JA. Gastric and gastro-oesophageal cancer therapy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2005;6:2805-2812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hu JK, Chen ZX, Zhou ZG, Zhang B, Tian J, Chen JP, Wang L, Wang CH, Chen HY, Li YP. Intravenous chemotherapy for resected gastric cancer: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:1023-1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hu JK, Li CM, Chen XZ, Chen ZX, Zhou ZG, Zhang B, Chen JP. The effectiveness of intravenous 5-fluorouracil-containing chemotherapy after curative resection for gastric carcinoma: A systematic review of published randomized controlled trials. J Chemother. 2007;19:359-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Practice guidelines in oncology-version V.1. 2018;(gastric cancer) Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/gastric.pdf. |

| 8. | Kilickap S, Yalcin S, Ates O, Tekuzman G. The first line systemic chemotherapy in metastatic gastric carcinoma: A comparison of docetaxel, cisplatin and fluorouracil (DCF) versus cisplatin and fluorouracil (CF); versus epirubicin, cisplatin and fluorouracil (ECF) regimens in clinical setting. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:208-212. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Babu KG, Chaudhuri T, Lakshmaiah KC, Dasappa L, Jacob LA, Babu M, Rudresha AH, Lokesh KN, Rajeev LK. Efficacy and safety of first-line systemic chemotherapy with epirubicin, cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil and docetaxel, cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil regimens in locally advanced inoperable or metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: A prospective phase II study from South India. Indian J Cancer. 2017;54:47-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Roth AD, Fazio N, Stupp R, Falk S, Bernhard J, Saletti P, Köberle D, Borner MM, Rufibach K, Maibach R, Wernli M, Leslie M, Glynne-Jones R, Widmer L, Seymour M, de Braud F; Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research. Docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil; docetaxel and cisplatin; and epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil as systemic treatment for advanced gastric carcinoma: a randomized phase II trial of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3217-3223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gao H, Ding X, Wei D, Tao XU, Cheng P. Docetaxel versus epirubicin combined with cisplatin, leucovorin and fluorouracil for advanced gastric carcinoma as first line therapy: a randomized clinical trial. Chin Clin Oncol. 2010;15:529-533. |

| 12. | Teker F, Yilmaz B, Kemal Y, Kut E, Yucel I. Efficacy and safety of docetaxel or epirubicin, combined with cisplatin and fluorouracil (DCF and ECF), regimens as first line chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer: a retrospective analysis from Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:6727-6732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009;3:e123-e130. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12275] [Cited by in RCA: 12887] [Article Influence: 444.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Wells GA, Shea BJ, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M. The newcastle-ottawa scale (nos) for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies in meta-analysis. Appl Eng Agric. 2014;18:727-734. |

| 16. | Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4738] [Cited by in RCA: 4954] [Article Influence: 275.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (version 5.1.0). London: The Cochrane Collaboration 2011; . |

| 18. | Sadighi S, Mohagheghi MA, Montazeri A, Sadighi Z. Quality of life in patients with advanced gastric cancer: a randomized trial comparing docetaxel, cisplatin, 5-FU (TCF) with epirubicin, cisplatin, 5-FU (ECF). BMC Cancer. 2006;6:274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Abbasi SY, Taani HE, Saad A, Badheeb A, Addasi A. Advanced gastric cancer in jordan from 2004 to 2008: a study of epidemiology and outcomes. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2011;4:122-127. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Shah MA, Janjigian YY, Stoller R, Shibata S, Kemeny M, Krishnamurthi S, Su YB, Ocean A, Capanu M, Mehrotra B, Ritch P, Henderson C, Kelsen DP. Randomized Multicenter Phase II Study of Modified Docetaxel, Cisplatin, and Fluorouracil (DCF) Versus DCF Plus Growth Factor Support in Patients With Metastatic Gastric Adenocarcinoma: A Study of the US Gastric Cancer Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3874-3879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Slagter AE, Jansen EPM, van Laarhoven HWM, van Sandick JW, van Grieken NCT, Sikorska K, Cats A, Muller-Timmermans P, Hulshof MCCM, Boot H, Los M, Beerepoot LV, Peters FPJ, Hospers GAP, van Etten B, Hartgrink HH, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, van Hillegersberg R, van der Peet DL, Grabsch HI, Verheij M. CRITICS-II: a multicentre randomised phase II trial of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery versus neo-adjuvant chemotherapy and subsequent chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery versus neo-adjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery in resectable gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fujitani K, Yang HK, Mizusawa J, Kim YW, Terashima M, Han SU, Iwasaki Y, Hyung WJ, Takagane A, Park DJ, Yoshikawa T, Hahn S, Nakamura K, Park CH, Kurokawa Y, Bang YJ, Park BJ, Sasako M, Tsujinaka T; REGATTA study investigators. Gastrectomy plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric cancer with a single non-curable factor (REGATTA): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:309-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 534] [Cited by in RCA: 508] [Article Influence: 56.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wagner AD, Grothe W, Haerting J, Kleber G, Grothey A, Fleig WE. Chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on aggregate data. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2903-2909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 833] [Cited by in RCA: 896] [Article Influence: 47.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, Majlis A, Constenla M, Boni C, Rodrigues A, Fodor M, Chao Y, Voznyi E, Risse ML, Ajani JA; V325 Study Group. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991-4997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1331] [Cited by in RCA: 1458] [Article Influence: 76.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wagner AD, Syn NL, Moehler M, Grothe W, Yong WP, Tai BC, Ho J, Unverzagt S. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;8:CD004064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 422] [Article Influence: 52.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Petrioli R, Roviello G, Zanotti L, Roviello F, Polom K, Bottini A, Marano L, Francini E, Marrelli D, Generali D. Epirubicin-based compared with docetaxel-based chemotherapy for advanced gastric carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;102:82-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chen XL, Chen XZ, Yang C, Liao YB, Li H, Wang L, Yang K, Li K, Hu JK, Zhang B, Chen ZX, Chen JP, Zhou ZG. Docetaxel, cisplatin and fluorouracil (DCF) regimen compared with non-taxane-containing palliative chemotherapy for gastric carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Al-Batran SE, Pauligk C, Homann N, Hartmann JT, Moehler M, Probst S, Rethwisch V, Stoehlmacher-Williams J, Prasnikar N, Hollerbach S, Bokemeyer C, Mahlberg R, Hofheinz RD, Luley K, Kullmann F, Jäger E. The feasibility of triple-drug chemotherapy combination in older adult patients with oesophagogastric cancer: a randomised trial of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (FLOT65+). Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:835-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fujii M. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer: ongoing phase III study of S-1 alone versus S-1 and docetaxel combination (JACCRO GC03 study). Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13:201-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wang J, Xu R, Li J, Bai Y, Liu T, Jiao S, Dai G, Xu J, Liu Y, Fan N, Shu Y, Ba Y, Ma D, Qin S, Zheng L, Chen W, Shen L. Randomized multicenter phase III study of a modified docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil regimen compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced or locally recurrent gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:234-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Petrelli F, Tomasello G, Ghidini M, Passalacqua R, Barni S. Modified schedules of DCF chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review of efficacy and toxicity. Anticancer Drugs. 2017;28:133-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Van Cutsem E, Boni C, Tabernero J, Massuti B, Middleton G, Dane F, Reichardt P, Pimentel FL, Cohn A, Follana P, Clemens M, Zaniboni A, Moiseyenko V, Harrison M, Richards DA, Prenen H, Pernot S, Ecstein-Fraisse E, Hitier S, Rougier P. Docetaxel plus oxaliplatin with or without fluorouracil or capecitabine in metastatic or locally recurrent gastric cancer: a randomized phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:149-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Tebbutt NC, Cummins MM, Sourjina T, Strickland A, Van Hazel G, Ganju V, Gibbs D, Stockler M, Gebski V, Zalcberg J; Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group. Randomised, non-comparative phase II study of weekly docetaxel with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil or with capecitabine in oesophagogastric cancer: the AGITG ATTAX trial. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:475-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kimura Y, Yano H, Taniguchi H, Iwazawa T, Danno K, Kagara N, Kanoh T, Ohnishi T, Tono T, Nakano Y, Monden T, Imaoka S. A phase I study of bi-weekly docetaxel for recurrent or advanced gastric cancer patients whose disease progressed by prior chemotherapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:747-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lee KW, Kim BJ, Kim MJ, Han HS, Kim JW, Park YI, Park SR. A Multicenter Randomized Phase II Study of Docetaxel vs. Docetaxel Plus Cisplatin vs. Docetaxel Plus S-1 as Second-Line Chemotherapy in Metastatic Gastric Cancer Patients Who Had Progressed after Cisplatin Plus Either S-1 or Capecitabine. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49:706-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Smith TJ, Bohlke K, Armitage JO. Recommendations for the Use of White Blood Cell Growth Factors: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:511-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Aapro MS, Bohlius J, Cameron DA, Dal Lago L, Donnelly JP, Kearney N, Lyman GH, Pettengell R, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Walewski J, Weber DC, Zielinski C; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. 2010 update of EORTC guidelines for the use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to reduce the incidence of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia in adult patients with lymphoproliferative disorders and solid tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:8-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 735] [Cited by in RCA: 767] [Article Influence: 51.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Li CP, Chen JS, Chen LT, Yen CJ, Lee KD, Su WP, Lin PC, Lu CH, Tsai HJ, Chao Y. A phase II study of weekly docetaxel and cisplatin plus oral tegafur/uracil and leucovorin as first-line chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1343-1348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Liu Y, Zhao G, Xu Y, He X, Li X, Chen H, Wu Q, Yao S, Yan G, Chen T. Multicenter Phase 2 Study of Peri-Irradiation Chemotherapy Plus Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy With Concurrent Weekly Docetaxel for Inoperable or Medically Unresectable Nonmetastatic Gastric Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;98:1096-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |