Published online Feb 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i4.452

Peer-review started: October 26, 2018

First decision: November 29, 2018

Revised: December 24, 2018

Accepted: January 23, 2019

Article in press: January 24, 2019

Published online: February 26, 2019

Processing time: 124 Days and 10.1 Hours

A low-volume polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution that combines ascorbic acid with PEG-based electrolyte solution (PEG-ASC) is gaining mainstream acceptance for bowel preparation due to reduced volume and improved taste. Although several reports showed that bowel preparation with PEG-ASC volume lower than 2.0 L with laxative agents could be an alternative to traditional preparation regimen, the cleansing protocols have not been fully investigated.

To evaluate the cleansing efficacy of 1.2 L PEG-ASC solution comparing with 2.0 L PEG electrolyte (PEG-ELS) for bowel preparations.

A randomized, single-blinded, open-label, single-center, non-inferiority study was conducted. In total, 312 Japanese adult patients (aged > 18 years) who underwent colonoscopy were enrolled. Patients were randomly allocated to bowel lavage with either 1.2 L of PEG-ASC solution with at least 0.6 L of an additional clear fluid (1.2 L PEG-ASC group) or 2.0 L of PEG-ELS (PEG-ELS group). Then, 48 mg of sennoside was administered at bedtime on the day before colonoscopy, and the designated drug solution was administered at the hospital on the day of colonoscopy. Bowel cleansing was evaluated using the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS). The volume of fluid intake and required time for bowel preparation were evaluated. Furthermore, compliance, patient tolerance, and overall acceptability were evaluated using a patient questionnaire, which was assessed using a visual analog scale.

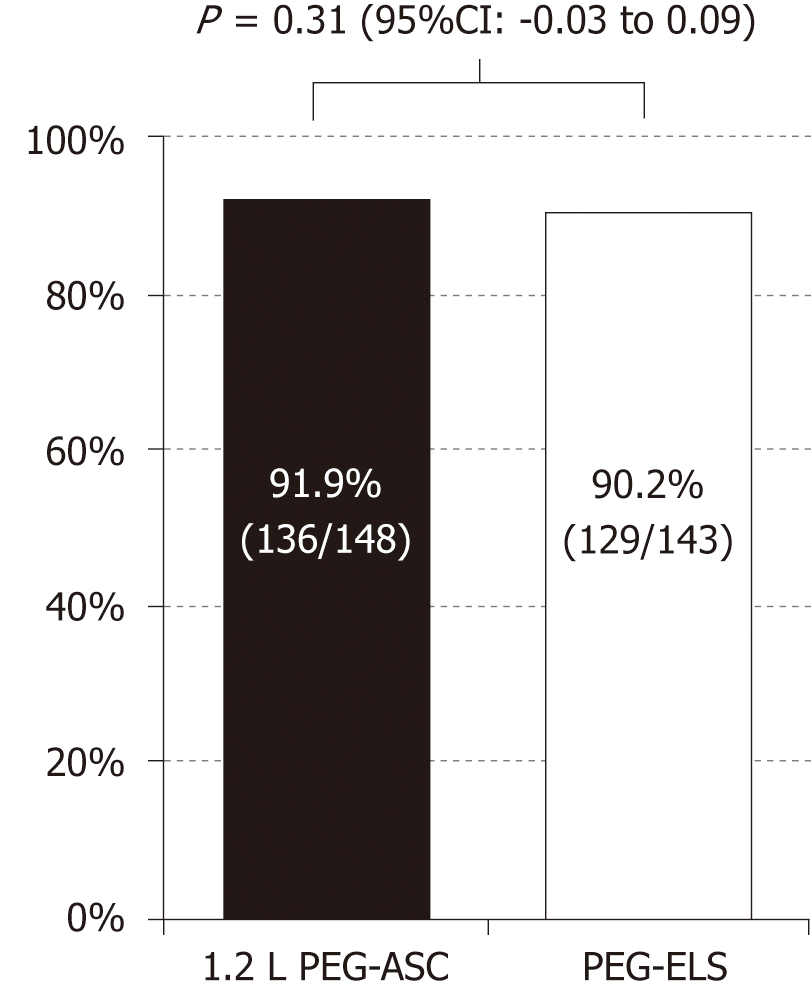

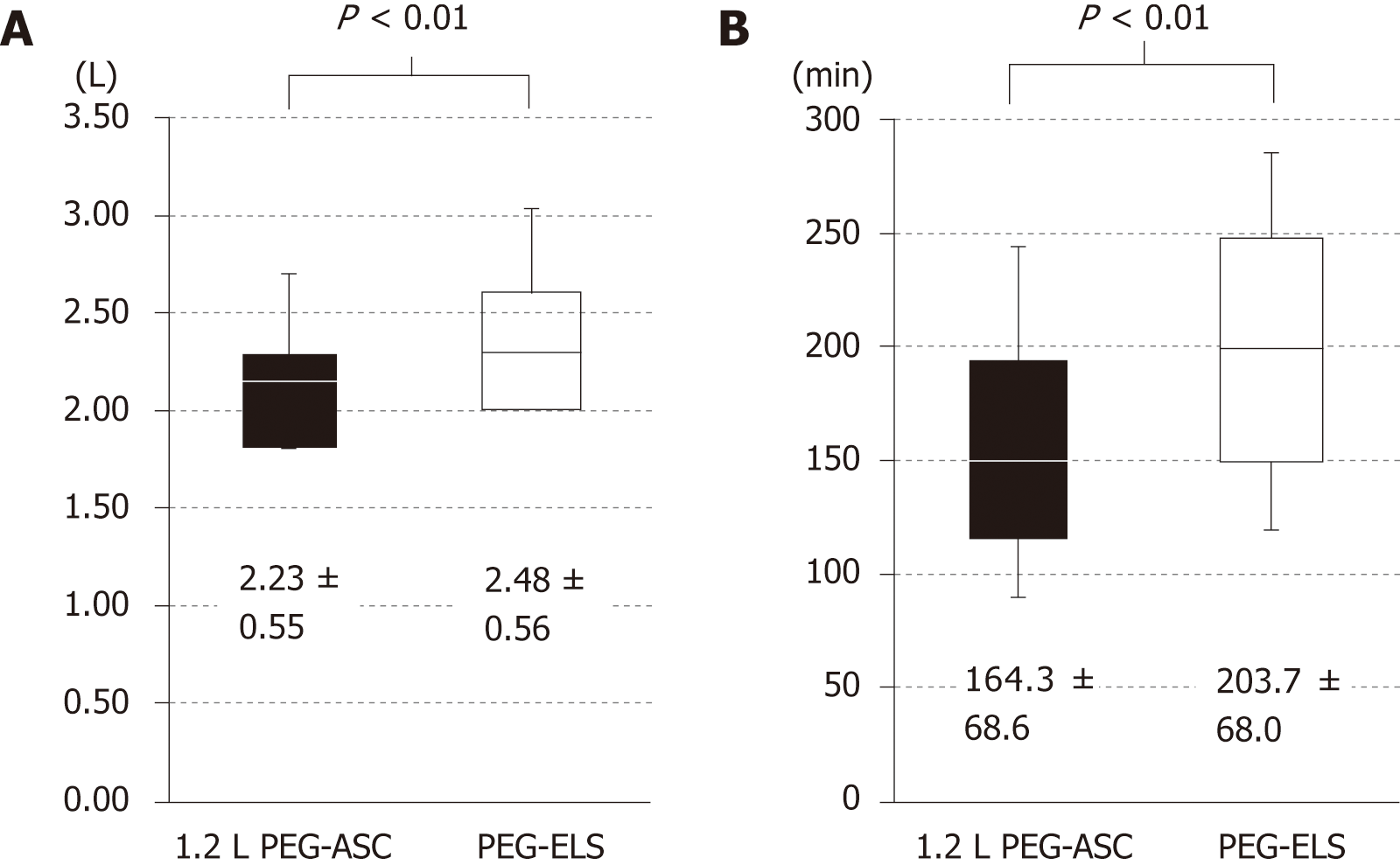

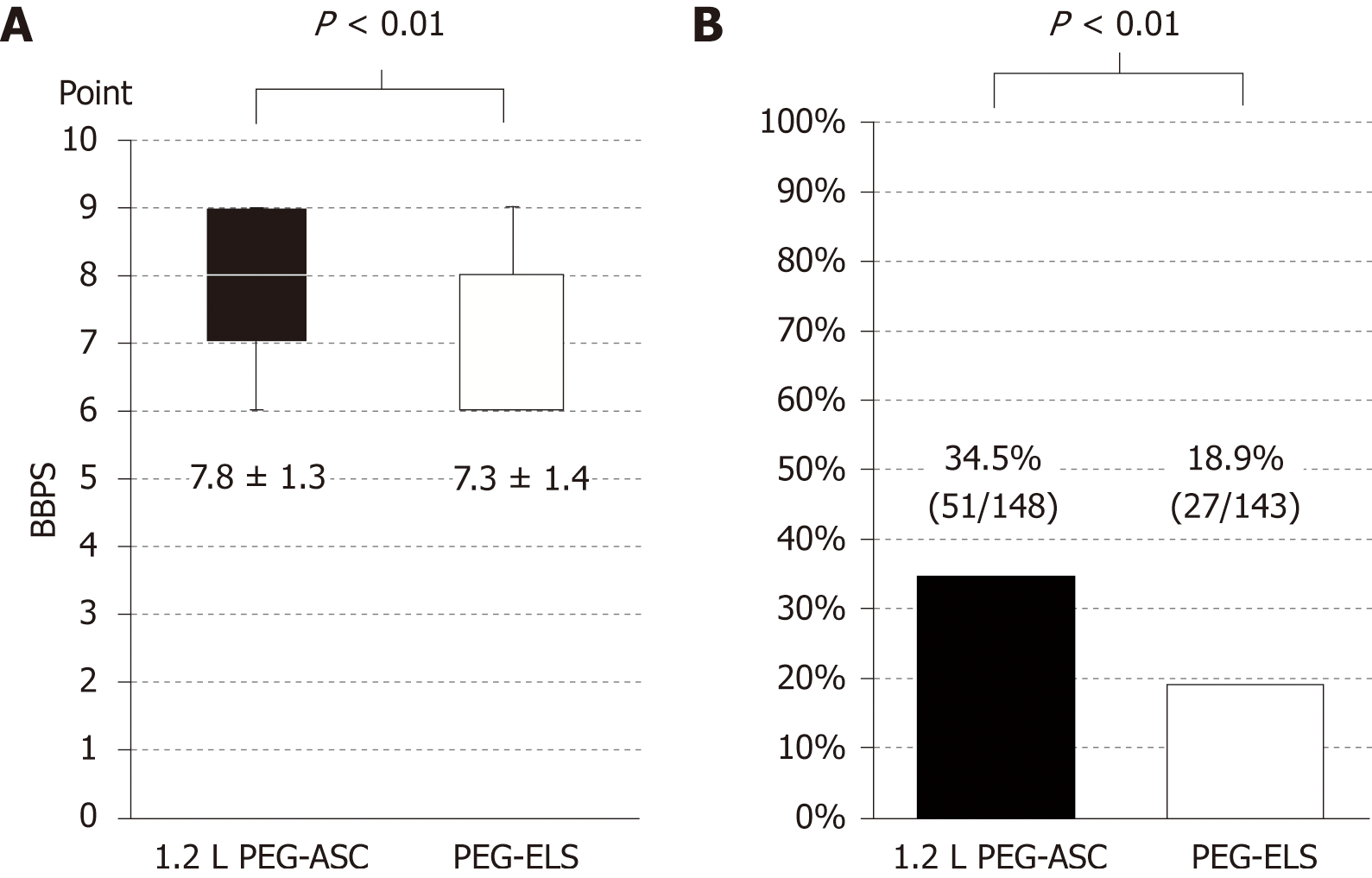

In total, 291 patients (1.2 L PEG-ASC group, 148; PEG-ELS group, 143) completed the study. There was no significant difference in successful cleansing, defined as a BBPS score ≥ 2 in each segment, between the two groups (1.2 L PEG-ASC group, 91.9%; PEG-ELS group, 90.2%; 95%CI: -0.03-0.09). The required time for bowel preparation was significantly shorter (164.95 min ± 68.95 min vs 202.16 min ± 68.69 min, P < 0.001) and the total fluid intake volume was significantly lower (2.23 L ± 0.55 L vs 2.47 L ± 0.56 L, P < 0.001) in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group than in the PEG-ELS group. Palatability, acceptability of the volume of solution, and overall acceptability evaluated using a patient questionnaire, which was assessed by the visual analog scale, were significantly better in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group than in the PEG-ELS group (7.70 cm ± 2.57 cm vs 5.80 cm ± 3.24 cm, P < 0.001). No severe adverse event was observed in each group.

The 1.2 L PEG-ASC solution was non-inferior to the 2.0 L PEG-ELS solution in terms of cleansing efficacy and had better acceptability among Japanese patients.

Core tip: Adequate bowel preparation is essential to improve colonoscopy quality. Volume and palatability of bowel cleansing agents are important determinants of tolerability, acceptability, and efficacy. This randomized study evaluated the non-inferiority of 1.2 L polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid (PEG-ASC) plus sennoside to 2.0 L PEG electrolyte (PEG-ELS) solutions plus sennoside for outpatient bowel preparation. The 1.2 L PEG-ASC and 2.0 L PEG-ELS solutions are clinically equivalent with respect to cleansing efficacy. Furthermore, the 1.2 L PEG-ASC solution was superior to 2.0 L PEG-ELS solution in terms of acceptability, and it was associated with a shorter required time for bowel preparation and a lower volume of fluid intake.

- Citation: Tamaki H, Noda T, Morita M, Omura A, Kubo A, Ogawa C, Matsunaka T, Shibatoge M. Efficacy of 1.2 L polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid for bowel preparations. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(4): 452-465

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i4/452.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i4.452

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains one of the most challenging diseases to treat worldwide and it is one of the leading causes of cancer death[1]. Because it is widely accepted that the adenoma-carcinoma and serrated polyp pathways play critical roles in the development of CRC, the main targets for screening colonoscopy for the prevention of CRC occurrence and deaths are adenomas and sessile serrated polyps[2-4]. Moreover, superficial curable cancers including flat or non-polypoid precursors should be treated as well. Colonoscopic polypectomy is the best diagnostic and therapeutic method, and removal of such precursor lesions during screening colonoscopy prevents death from CRC[5,6]. However, the miss rate for neoplastic polyps is estimated to be 16.8%-28%[7-9]. Several factors such as poor bowel cleansing, areas of poor visualization, and inadequate colonoscope withdrawal time were suggested as reasons for the increasing miss rate[10-15].

Inadequate bowel preparation is a serious matter on screening colonoscopy because it may result in a higher adenoma miss rate, prolonged procedure time, lower colonoscopy completion rate, and increased cost because of the need for an earlier repeat examination[16-18]. An ideal bowel preparation agent should achieve high-quality bowel preparation and should be inexpensive and well-tolerated by a high proportion of patients[19]. Furthermore, the cleansing protocol should be simple and suitable for inpatients and outpatients. However, no available agent has completely met these criteria.

Currently, polyethylene glycol-based electrolyte solution (PEG-ELS) is used most commonly for bowel preparation owing to its cleansing efficacy and safety[20]. Based on meta-analysis, split-dose regimens of 4.0 L of PEG-ELS increase the quality of colon cleansing and have higher acceptability compared to day-before preparations[21-23]. However, oral intake of a high-volume cleansing solution results in reduced tolerability and low adherence and consequently low-quality bowel preparations.

Nowadays, a low-volume PEG solution that combines ascorbic acid with PEG-ELS (PEG-ASC) is gaining mainstream acceptance due to reduced volume and improved taste. In Western countries, approximately 2.0 L of PEG-ASC achieved non-inferior efficacy for bowel cleansing with better acceptability and fewer side effects than the standard-volume PEG-ELS[24-28]. In addition, recent reports from Japan and Korea suggested appropriate volumes of PEG-ASC to be lower than 2.0 and laxative agents combined with low-residue diet prior to bowel cleansing showed similar cleansing effect to traditional regimen[29-32]. Taking these results into consideration, bowel preparation with PEG-ASC volume lower than 2.0 L with laxative agents in the optimized protocol can be alternative to traditional preparation regimen.

However, cleansing protocols with reduced volume using PEG-ASC have not been fully investigated. Therefore, we conducted the current study to evaluate the cleansing efficacy, acceptability, and safety of the 1.2 L PEG-ASC plus sennoside regimen comparing with the 2.0 L PEG-ELS regimen as an outpatient bowel preparation for afternoon colonoscopy in a Japanese population.

A randomized, single-blinded, open-label, single-center, non-inferiority study was conducted. This trial is registered at UMIN (UMIN000020904), and its protocol was approved by the Investigational Review Board of Takamatsu Red Cross Hospital. All patients provided written informed consent for their participation.

A total of 312 Japanese adult patients [> 18 years; 177 men, 135 women; mean age 63.0 (range 18-89) years] who underwent colonoscopy at Takamatsu Red Cross Hospital between December 2014 and March 2016 were enrolled in the study. Patients were excluded if they had known or suspected bowel obstruction, ileus, and perforation. Patients with history of bowel resection, significant gastroparesis or gastric outlet obstruction, toxic colitis or megacolon, severe chronic renal failure [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 30 mL/min·1.73 m2), severe congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association class III or IV), sustained tachyarrhythmia, and uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 170 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 100 mmHg) were excluded. Patients requiring hospitalization and pregnant or lactating women were also excluded.

Before the start of the study, a randomization list was computer generated using a method of randomly permuted blocks of four patients. Eligible patients were randomly assigned to bowel lavage with either 1.2 L of PEG-ASC or 2.0 L of PEG-ELS solution in numerical order of acceptance into the study. The randomization number was strictly given according to the order of patient enrollment, with each patient assigned the first available number on the randomization list. The randomization number, or the reason for not enrolling the patient, was reported for each patient in the appropriate forms. In this single-blind randomized controlled trial, patients were aware of the bowel lavage assigned, and the investigator and assessors were blinded to group allocation.

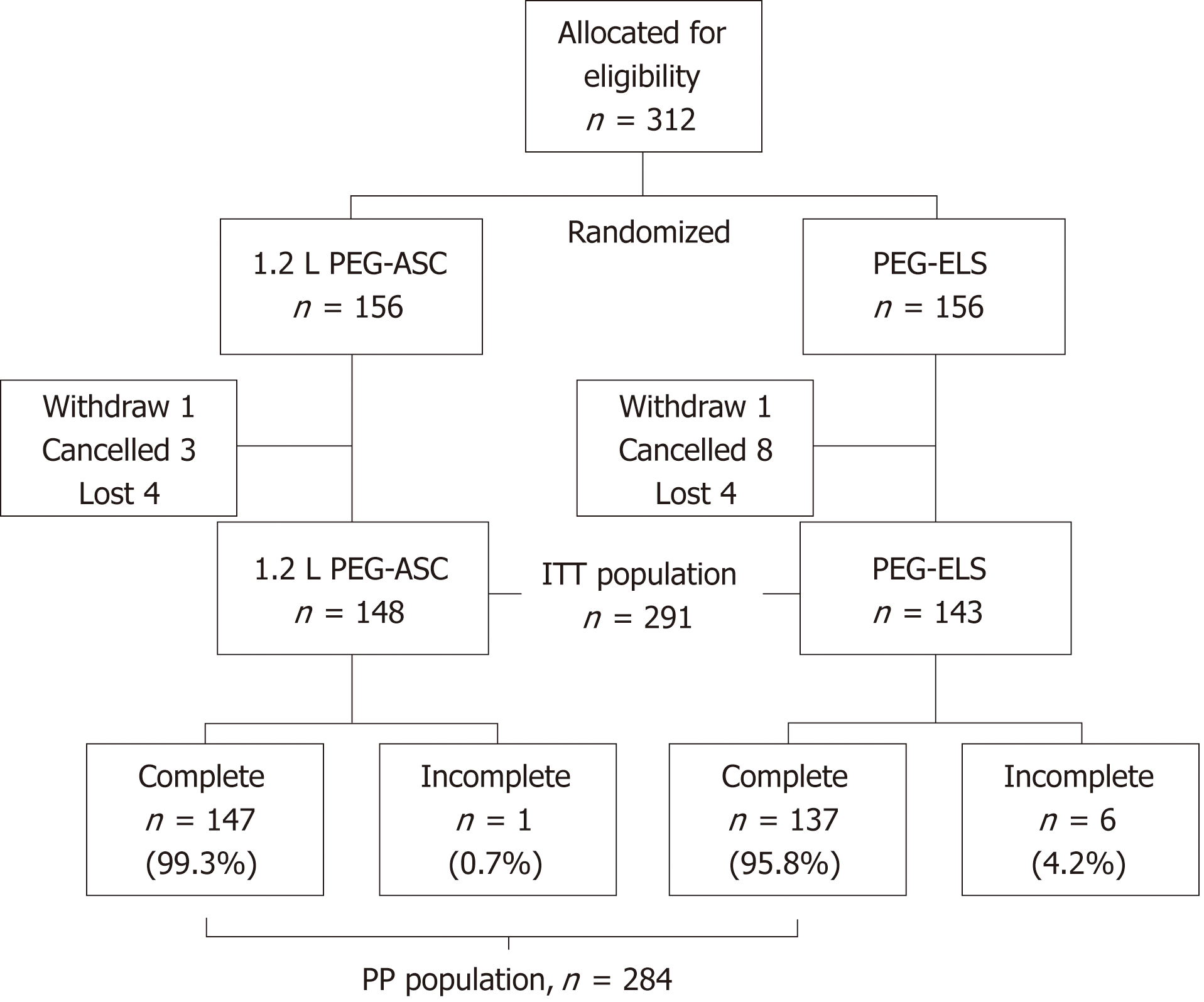

The primary population was the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, which was defined as all randomly assigned patients who received the bowel lavage. The secondary population was the per-protocol (PP) population, which was defined as randomly assigned patients who completed the recommended total fluid intake.

At the screening visit, the patient’s baseline characteristics, including demographic information and past surgical and medical therapy, were obtained. Patients enrolled in the study received verbal and written instructions on bowel preparation, including how the product should be taken. They were also informed of the potential side effects of the preparation solution as well as the drawbacks of an aborted procedure. Furthermore, dietary instruction indicating foods recommended to be taken (e.g., rice, noodles, bread, banana) and to be avoided (e.g., uncooked vegetable, vegetable or fruits with seeds, seaweeds, konjac) were given.

This study had three protocols for bowel preparation: (1) low-residue diet was started on the day before colonoscopy; (2) 48 mg of sennoside was administered on the day before colonoscopy; and (3) 1.2 L PEG-ASC or 2 L PEG-ELS solution was administered the day of colonoscopy on the designated group. Specially, on the day before colonoscopy, all patients were instructed to ingest a low-residue food until 8:00 pm. Only clear fluids were allowed after 8:00 pm, and 48 mg of sennoside was administered at bedtime (8:00 pm to 12:00 pm).

On the day of the colonoscopy, patients received either PEG-ASC (Moviprep®: EA Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan, each liter contained 100.0 g of macrogol 4000, 7.5 g of sodium sulfate, 2.7 g of sodium chloride, 1.0 g of potassium chloride, 4.7 g of ascorbic acid, 5.9 g of sodium ascorbate, and lemon flavoring) or PEG-ELS (Niflec®: EA Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan, each liter contained 59.0 g of macrogol 4000, 5.7 g of sodium sulfate, 1.5 g of sodium chloride, 0.7 g of potassium chloride, 1.7 g of sodium bicarbonate, and lemon flavoring). Patients in the first arm received 1.2 L of PEG-ASC at a rate of 0.2 L every 10 min to 15 min followed by at least 0.6 L of an additional clear fluid [1.2 L of PEG-ASC (1.2 L PEG-ASC) group]. Patients could take clear fluid while taking the cleansing solution, and they were instructed to take additional clear fluid until bowel cleansing was completed. There was no limitation to the amount of additional clear fluid. Patients in the second arm received 2.0 L of PEG-ELS at a rate of 0.25 L every 15 min (PEG-ELS group).

Before the start of the colonoscopy, patients filled in the three-item questionnaire: (1) please evaluate the taste of the cleansing lavage [assessed by visual analog scale (VAS): terrible - good]; (2) please evaluate the volume of the cleansing lavage (assessed by VAS: difficult to ingest - easy to ingest); and (3) please make a comprehensive evaluation of the cleansing lavage (assessed by VAS: terrible - good). The volume of fluid intake, required time for bowel preparation, and the time interval between the completion of bowel preparation and the start of colonoscopy were recorded. All adverse events were documented, classified, and graded according to the World Health Organization recommendations for the evaluation of active and subjective toxicity.

The colonoscopies, performed by skillful endoscopists who have experienced at least 1000 colonoscopies, were scheduled between 1:00 pm and 4:30 pm according to the normal standard of care. Bowel cleansing was evaluated using the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS), which is a validated scoring system with scores between 0 and 9, where 9 is the best score[33]. The score is composed of three sub-scores between 0 and 3, evaluating the cleansing effect in each colon segment: The right colon (including the cecum and ascending colon), the transverse colon (including the hepatic and splenic flexures), and the left colon (including the descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum). BBPS sub-score ≥ 2 in each segment was defined as successful cleansing according to previous report[34].

The primary endpoint was the successful cleansing rate defined as BBPS sub-score ≥ 2 in each segment. Secondary endpoints were cleansing quality evaluated by BBPS, frequency of cleansing operation to remove foam or bubbles, the time interval between the completion of bowel preparation and the start of colonoscopy, polyp and adenoma detection rate defined as proportion of the total number of polyps and adenomas divided by the number of colonoscopies (PDR and ADR, respectively), and advanced adenoma detection rate (AADR) calculated as the percentage of patients in each group who had at least one advanced adenoma defined as any adenoma or sessile serrated polyp ≥ 10 mm in diameter, with villous components or high-grade dysplasia regardless of size, and sessile serrated polyps with dysplasia[35]. Furthermore, volume of fluid intake, required time for bowel preparation, patient tolerance, and acceptability evaluated using patient questionnaire which consists of evaluation for palatability, volume, and overall acceptability were evaluated.

The patient sample size was determined by considering the results of phase I and II studies on bowel preparation with PEG-ASC or PEG-ELS conducted by Ajinomoto Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. The sample size was determined as 143 subjects per treatment group to have > 80% power to detect the non-inferiority of the PEG-ASC to PEG-ELS with a two-sided significance value of 5% (95%CI for evaluation) and a non-inferiority margin of 10%. Considering possible dropouts, 150 subjects were targeted for recruitment for each treatment group.

Baseline patient characteristics were compared using Student’s t-test for independent samples or Pearson’s χ2 test, as appropriate. Successful cleansing rate, frequency of cleansing operation to remove foam or bubbles, PDR, ADR, and AADR were compared using Pearson’s χ2 test, and BBPS score, total volume of fluid intake, required time for bowel preparation, and patient acceptability assessed by VAS were compared using Mann-Whitney U-test between the two groups. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SE, and categorical data are expressed as percentages. P values < 0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States).

A total of 312 Japanese patients (156 in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group and 156 in the PEG-ELS group) were enrolled between December 2014 and March 2016. One patient in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group and one patient in the PEG-ELS group withdrew from the study before examination. Three patients in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group and eight in the PEG-ELS group cancelled the examination, and the remaining four patients in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group and four patients in the PEG-ELS group were lost to follow-up. Finally, 291 patients (1.2 L PEG-ASC group, 148; PEG-ELS group, 143) completed the study (94.9% and 91.7%, respectively; ITT population). A total of 147 patients in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group and 137 patients in the PEG-ELS group completed the recommended total fluid intake (99.3% and 95.8%, respectively; PP population, Figure 1).

The clinical characteristics of the enrolled patients in the two groups are shown in Table 1. No significant differences were identified in terms of demographic characteristics (mean age, sex, constipation, experience of abdominal operation, hypertension, diabetes, and experience of colonoscopy) or indications for colonoscopy.

| 1.2 L PEG-ASC (n = 156) | PEG-ELS (n = 156) | Total (n = 312) | P value | |

| Age (mean, range) | 62.6 (19-89) | 63.5 (24-89) | 63.0 (19-89) | 0.21 |

| Sex (male, %) | 93 (59.6) | 84 (53.8) | 177 (56.7) | 0.30 |

| Constipation, n (%) | 39 (25.0) | 38 (24.4) | 77 (24.7) | 0.89 |

| Abdominal operation, n (%) | 58 (37.2) | 55 (35.3) | 113 (36.2) | 0.72 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 36 (23.1) | 26 (16.7) | 62 (19.9) | 0.16 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 12 (7.7) | 15 (9.6) | 27 (8.7) | 0.54 |

| Experience of colonoscopy, n (%) | 89 (57.0) | 87 (55.8) | 176 (56.4) | 0.81 |

| Indications for colonoscopy, n (%) | ||||

| Occult blood test-positive | 76 (48.7) | 70 (44.9) | 146 (46.8) | 0.50 |

| Surveillance | 30 (19.2) | 27 (17.3) | 57 (18.3) | 0.66 |

| Screening | 21 (13.5) | 22 (14.1) | 43 (13.8) | 0.87 |

| Blood in stool | 10 (6.4) | 13 (8.3) | 23 (7.4) | 0.52 |

| Abdominal pain | 5 (3.2) | 6 (3.9) | 13 (4.2) | 0.76 |

| Constipation | 4 (2.6) | 5 (3.2) | 9 (2.9) | 0.74 |

| Diarrhea | 2 (1.3) | 5 (3.2) | 7 (2.2) | 0.44 |

| Other reason | 8 (5.1) | 8 (5.1) | 16 (5.1) | 0.80 |

There was no significant difference in successful cleansing, defined as a BBPS sub-score ≥ 2 in each segment, between the two groups (1.2 L PEG-ASC group, 91.9%; PEG-ELS group, 90.2%; 95%CI: -0.03-0.09 in the ITT population, 1.2 L PEG-ASC group, 91.8%; PEG-ELS group, 90.5%; 95%CI: -0.02-0.08 in the PP population; Figure 2). Table 2 shows the successful cleansing rate evaluated by BBPS according to the colonic segment. Using a segmental score of 2-3 as an indication of adequate cleansing, there was also no significant difference between preparations in each segment. Thus, the PEG-ASC demonstrated non-inferiority to the PEG-ELS with a two-sided significance value of 5% and a non-inferiority margin of 10%.

| 1.2 L PEG-ASC (n = 148) | PEG-ELS (n = 143) | P value | |

| Right | 93.9 (139) | 94.4 (135) | 0.86 |

| Transverse | 95.9 (142) | 95.1 (136) | 0.73 |

| Left | 95.9 (142) | 92.3 (132) | 0.19 |

| Over all | 91.9 (136) | 90.2 (129) | 0.61 |

The total volume of fluid intake was significantly lower (2.23 L ± 0.55 L vs 2.47 L ± 0.56 L, P < 0.01; Figure 3A), and the required time for bowel preparation was significantly shorter in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group than in the PEG-ELS group (164.3 min ± 68.6 min vs 203.7 min ± 68.0 min, P < 0.01; Figure 3B). The time interval was significantly longer in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group than in the PEG-ELS group (147.3 min ± 66.2 min vs 115.9 min ± 54.7 min, P < 0.01). The cleansing quality evaluated by BBPS, defined as the sum of each segmental score, was superior in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group than in the PEG-ELS group (7.80 ± 1.37 vs 7.30 ± 1.40, P < 0.01 in the ITT population, 7.76 ± 1.35 vs 7.29 ± 1.37, P < 0.01 in the PP population; Figure 4A). Additionally, there was no significant difference in the successful cleansing rates according to various factors (age 70 years and older; female sex; constipation; diabetes; and history of abdominal operation) between the two groups (Table 3). However, foam or bubbles were observed more frequently in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group than in the PEG-ELS group (35.7% vs 19.7%, P < 0.01; Figure 4B). The PDR, ADR, and AADR in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group were comparable to those in the PEG-ELS group (PDR, 42.6% vs 47.6%, P = 0.39; ADR, 34.5% vs 39.1%, P = 0.41; AADR, 10.8% vs 13.2%, P = 0.52; Table 4).

| 1.2 L PEG-ASC | PEG-ELS | P-value | |

| Age (70 years old and older) | 89.8 (44) | 89.6 (43) | 0.77 |

| Sex (Female) | 93.2 (55) | 87.7 (57) | 0.46 |

| Constipation | 81.1 (30) | 88.6 (31) | 0.58 |

| Diabetes | 83.3 (10) | 81.3 (13) | 0.72 |

| History of abdominal operation | 93.1 (54) | 92.7 (51) | 0.77 |

| Variable | 1.2 L PEG-ASC (n = 148) | PEG-ELS (n = 143) | P value |

| PDR | 42.6 (63) | 47.6 (68) | 0.39 |

| ADR | 34.5 (51) | 39.1 (56) | 0.41 |

| AADR1 | 10.8 (16) | 13.2 (19) | 0.52 |

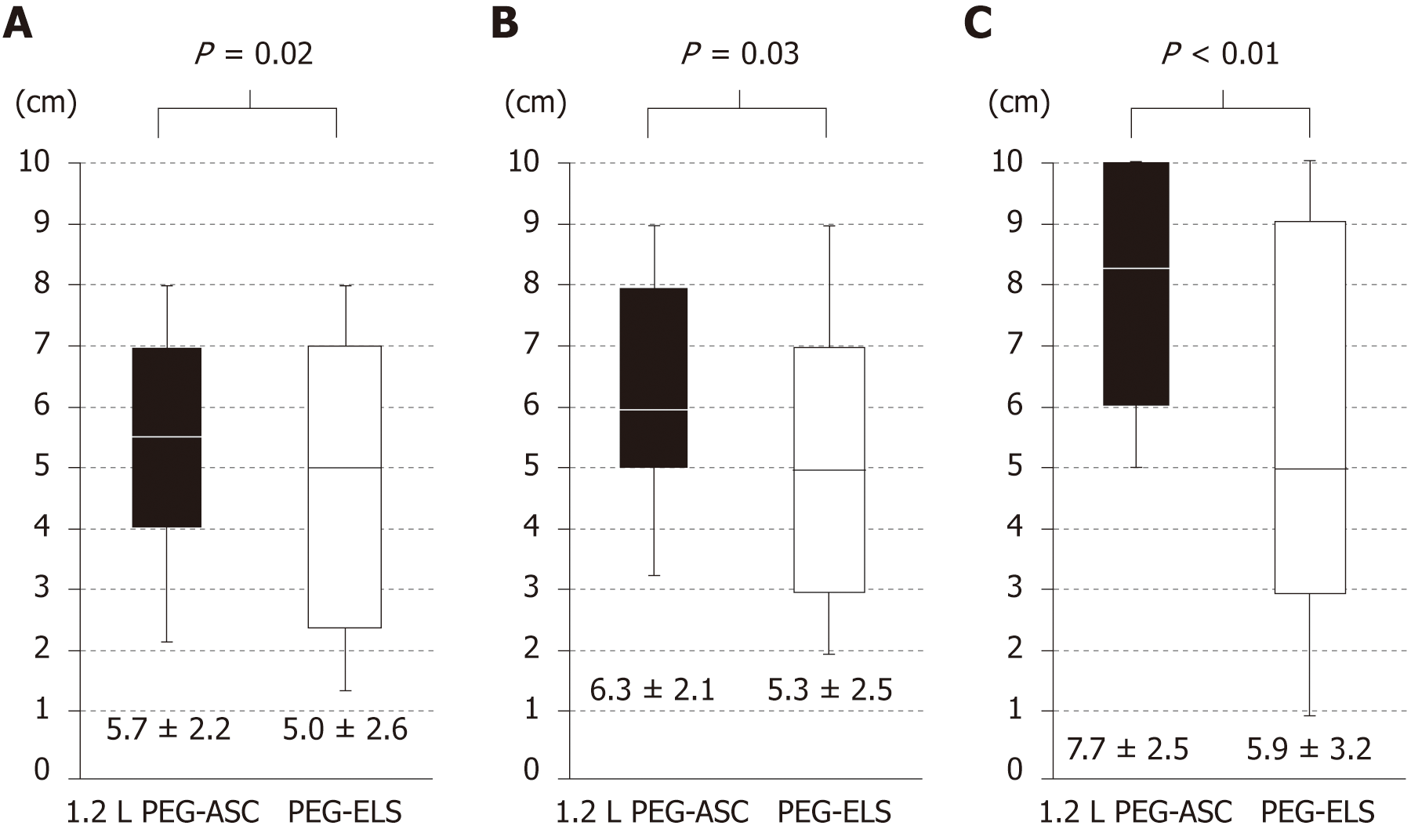

Although adherence with the recommended total fluid intake tended to be better in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group than in the PEG-ELS group, this was not statistically different (99.3% vs 95.6%, P = 0.11). Regarding patient acceptability evaluated by the patient questionnaire assessed by VAS, patients randomized to the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group reported a significantly superior palatability and acceptability in the volume of the solution than those randomized to the PEG-ELS group (5.7 cm ± 2.2 cm vs 5.0 cm ± 2.6 cm, P = 0.02; 6.3 cm ± 2.1 cm vs 5.3 cm ± 2.5 cm, P = 0.03, respectively; Figure 5A and B). Furthermore, overall acceptability was significantly better in the 1.2L PEG-ASC group than in the PEG-ELS group (7.70 cm ± 2.57 cm vs 5.80 cm ± 3.24 cm, P < 0.001; Figure 5C).

There were no significant differences in the incidence and type of adverse events between the 1.2L PEG-ASC and the PEG-ELS groups. The most common reported adverse events were nausea and abdominal discomfort; however, no major adverse event was reported in either group (Table 5).

| 1.2 L PEG-ASC | PEG-ELS | P value | |

| Nausea | 6.1 (9) | 12.6 (18) | 0.087 |

| Vomiting | 0.7 (1) | 2.8 (4) | 0.34 |

| Abdominal discomfort | 9.5 (14) | 7.7 (11) | 0.59 |

| Abdominal pain | 2.7 (4) | 3.5 (5) | 0.96 |

| Dizziness | 0 (0) | 2.1 (3) | 0.23 |

| Chill | 1.4 (2) | 2.1 (3) | 0.97 |

| No discomfort | 81.8 (120) | 76.2 (109) | 0.31 |

In this study, the 1.2 L PEG-ASC solution showed non-inferiority to the 2.0 L PEG-ELS solution in terms of the cleansing efficacy. Moreover, the 1.2 L PEG-ASC solution was superior to the 2.0 L PEG-ELS solution in terms of patient acceptability, and it was associated with a shorter time for bowel preparation, lower volume of fluid intake, and superior palatability. Furthermore, no major adverse events were reported in either group. Overall, this study demonstrated that the 1.2 L PEG-ASC solution plus sennoside is comparable to the 2.0 L PEG-ELS solution plus sennoside in bowel cleansing efficacy.

Traditional 4 L PEG regimen is widely accepted as a first recommended regimen for its safety and efficacy. However, ingestion of the large volume of solution and its unpleasant taste may result in poor acceptability and adherence. To improve these limitations, low-volume regimens that combine PEG and osmotic agents (e.g., ascorbic acid, sodium phosphate) or stimulant agents (e.g., bisacodyl, sennoside) are developed. Several studies compared 2 L PEG-ASC and traditional 4 L PEG regimen and concluded that 2 L PEG-ASC had comparable cleansing efficacy with better acceptability[27,36]. In contrast, 2 L PEG regimen combined with bisacodyl was reported to have comparable cleansing effect to traditional 4 L PEG regimen[37,38]. Furthermore, several groups in East Asia recently reported that the combination of PEG-ASC and bisacodyl or sennoside achieved to reduce the volume of cleansing solution to 1 L or 1.5 L with comparative cleansing effect and improved patient acceptability to 2 L PEG regimen combined with laxative or split-dose 2-L PEG-ASC. Tajika et al[29] reported that the 1.5 L PEG-ASC solution plus sennoside was superior to the 2 L PEG-ELS solution plus sennoside with respect to patient acceptability of bowel preparation for colonoscopy, and it was comparable to the 2.0 L PEG-ELS in bowel cleansing efficacy, tolerability, and safety. Moreover, the efficacy of bowel preparation with the 1.0 L PEG-ASC solution was reported in a prospective study from Japan[31] and two randomized studies from South Korea[32,39]. Although their protocol had differences in terms of the kind of the laxative (sennoside or bisacodyl), these studies concluded that the 1.0 L PEG-ASC solution had similar efficacy with the 2.0 L PEG-ELS solution in bowel preparation. These results support that the efficacy of the reduced dose of PEG-ASC solution to less than 2.0 L plus laxative is comparable to the traditional PEG regimen as bowel preparation. However, because there had not been specific criteria for adequate dosing, we performed a preliminary study by comparing the cleansing efficacy of 1.0 L, 1.2 L, and 1.5 L PEG-ASC solutions plus sennoside to determine the volume of PEG-ASC for our study (n = 25 in each group, data not shown). According to the results of the preliminary study, we determined the regimen to be evaluated: an instruction for patients to take low-residue diet and an administration of 48 mg of sennoside on the day before colonoscopy, followed by bowel preparation with 1.2 L of PEG-ASC and at least 0.6 L of additional clear fluid during procedure on the day of colonoscopy. As we expected, the current study demonstrates the non-inferiority of 1.2 L PEG-ASC solution to 2.0 L PEG-ELS solution for successful cleansing, defined as BBPS sub-score ≥ 2 in each segment in the ITT and PP population. Moreover, the sum of each BBPS segmental score was significantly higher in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group than in the 2.0 L PEG-ELS group.

Furthermore, our results demonstrate that the PDR, ADR, and AADR were comparable between the two groups, suggesting that similar visualization quality was achieved. ADR is recognized as a useful surrogate marker for CRC detection[40], and for every 1% increase in the ADR, there is a 3% decrease in CRC incidence and a 5% decrease in CRC-related mortality[41]. Although it is still controversial whether bowel cleansing influences ADR, several studies, including meta-analyses, have demonstrated that adequate bowel cleansing is associated with a higher ADR[16,42]. The ACG/American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy task force on quality colonoscopy recommended a minimum average risk screening ADR target of 25% in a combined male and female population (30% ADR in men and 20% ADR in women)[43]. The ADR in the current study, 34.5% in the 1.2L PEG-ASC group and 39.1% in the PEG-ELS group, is greater than the recommended value and suggests that both protocols have sufficient efficacy in bowel cleansing for screening colonoscopy.

The time interval between the bowel preparation and the start of colonoscopy was reported as one of the predicting factors affecting bowel cleansing effect as well as age, sex, diabetes, constipation, history of abdominal surgery, compliance with preparation instructions, and bowel preparation type. In the current study, the time interval was significantly longer in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group than in the PEG-ELS group (147.3 min ± 66.2 min vs 115.9 min ± 54.7 min, P < 0.01). This difference is considered to be due to the difference in the required time for bowel preparation between the two groups and fixed starting time of colonoscopy in both groups. Kim et al[44] reported the relationship in the time interval between the last PEG intake and the start of colonoscopy. Although they concluded that the optimal time interval was 5 h -6 h for the full-dose PEG method, there was no significant difference in the cleansing effect between the time intervals under 3 h and 5 h -6 h in the patients who received the PEG solution and colonoscopy on the same day. Therefore, we considered that the difference of 30 min in the time interval between the two groups in the current study did not have a potent influence on the evaluation of the cleansing effect.

The variant cleansing effect of PEG-ASC is considered to derive from the excessive ascorbic acid residues in the bowel lumen because its absorption mechanism saturates at a high dose[45]. Ascorbic acid residues can act as an osmotic laxative cooperating with PEG-ELS. In this respect, a risk of inducing intravascular volume depletion is alarming. Failure to maintain adequate hydration before, during, and after bowel preparation may increase the risk of severe and potentially fatal intravascular volume depletion-related complications such as fatal dysnatremia associated with PEG-ELS preparations or renal failure associated with sodium phosphate preparations[46-48]. Therefore, we excluded patients with renal dysfunction whose eGFR is < 30 mL/min·1.73 m2 or those with severe congestive heart failure, and patients were encouraged to take additional clear fluid other than the required 0.6 L throughout the bowel-preparation process to maintain hydration. In this study, the minimum volume of clear fluid to be ingested during procedure was 0.6 L, which was in accordance with the instruction provided by the drug package insert: half of the volume of the ingested PEG-ASC solution. However, sufficient fluid replacement more than 0.6 L is considered to contribute to avoiding intravascular volume depletion-related complications. Essentially, the total volume of fluid intake amounted to 2.23 L ± 0.55 L suggesting that 1.03 L ± 0.55 L of additional clear fluid was ingested by patients in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group. Consequently, no fatal dehydration-related complications were observed in the current study. In addition, there were no significant changes in eGFR before and after the procedure in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group (82.9 mL/min·1.73 m2 ± 1.9 mL/min·1.73 m2vs 81.5 mL/min·1.73 m2 ± 1.6 mL/min·1.73 m2, P = 0.17; data not shown). These results suggested that the volume of fluid intake was sufficient to maintain hydration in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group. Thus, our results demonstrated the safety of the bowel cleansing protocol with 1.2 L PEG-ASC solution with respect to intravascular volume depletion and renal dysfunction.

There are several limitations to this study. First, this study was conducted at a single center, limiting the generalizability of the results. Second, this study was performed in a single-blinded manner, and it may have possible influence on patient’s rating on the acceptability evaluated by the patient questionnaire. Third, dietary regimen on the day before colonoscopy was not even because it depended on individual response after a dietary instruction. Finally, we have to take the difference between the races and the region into consideration when we discuss the efficacy of bowel cleansing regimens. They can vary in effectiveness depending on the racial or regional groups because body dimensions, diet habits, and bowel transit time. etc., vary among population and are considered to affect the reactivity for cleansing agents. Although the efficacy of the combination of PEG-ASC lower than 2 L plus bisacodyl or sennoside was currently evaluated only in East Asia, they are thought to be effective in the population who are successfully treated with 2 L PEG-ELS plus laxative (e.g., South Asia[37] or Canada[38]). In this point of view, further studies in various races and regions are required to confirm the efficacy of PEG-ASC lower than 2.0 L plus laxative.

In summary, this study demonstrated that 1.2 L of PEG-ASC and 2.0 L of PEG-ELS are clinically equivalent with respect to cleansing efficacy, including ADR. The 1.2 L PEG-ASC regimen was superior to the 2.0 L PEG-ELS regimen in terms of the required time for bowel preparation, palatability, and acceptability. These results support that the 1.2 L PEG-ASC solution plus sennoside with prior low-residue diet is a suitable alternative to the standard bowel preparation with PEG-ELS in outpatients for afternoon colonoscopy.

Inadequate bowel preparation is a serious matter on screening colonoscopy because it may result in a higher adenoma miss rate, prolonged procedure time, lower colonoscopy completion rate, and increased cost because of the need for an earlier repeat examination.

Low-volume regimens that combine polyethylene glycol (PEG) and osmotic or stimulant agents are developed to improve acceptability. Although several reports showed that the combination of PEG plus ascorbic acid (PEG-ASC) solution lower than 2.0 L and laxative agents could be alternative to traditional preparation regimen, the cleansing protocols have not been fully investigated.

We aimed to evaluate the cleansing efficacy of 1.2 L PEG-ASC comparing with 2.0 L PEG electrolyte (PEG-ELS) combined with sennoside as bowel preparations for afternoon colonoscopy.

A randomized, single-blinded, open-label, single-center, non-inferiority study was conducted. In total, 312 Japanese adult patients (aged > 18 years) who underwent colonoscopy were enrolled. Patients were randomly allocated to bowel lavage with either 1.2 L of PEG-ASC solution with at least 0.6 L of an additional clear fluid (1.2L PEG-ASC group) or 2.0 L of PEG-ELS (PEG-ELS group). Then, 48 mg of sennoside was administered at bedtime on the day before colonoscopy, and the designated drug solution was administered at the hospital on the day of colonoscopy. Bowel cleansing was evaluated using the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS). The volume of fluid intake and required time for bowel preparation were evaluated. Furthermore, compliance, patient tolerance, and overall acceptability were evaluated using a patient questionnaire, which was assessed using a visual analog scale.

In total, 291 patients (1.2 L PEG-ASC group, 148; PEG-ELS group, 143) completed the study. There was no significant difference in successful cleansing, defined as a BBPS score ≥ 2 in each segment, between the two groups (1.2 L PEG-ASC group, 91.9%; PEG-ELS group, 90.2%; 95%CI: -0.03-0.09). The required time for bowel preparation was significantly shorter (164.95 min ± 68.95 min vs 202.16 min ± 68.69 min, P < 0.001) and the total fluid intake volume was significantly lower (2.23 L ± 0.55 L vs 2.47 L ± 0.56 L, P < 0.001) in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group than in the PEG-ELS group. Palatability, acceptability of the volume of solution, and overall acceptability evaluated using a patient questionnaire, which was assessed by the visual analog scale, were significantly better in the 1.2 L PEG-ASC group than in the PEG-ELS group (7.70 cm ± 2.57 cm vs 5.80 cm ± 3.24 cm, P < 0.001). No severe adverse event was observed in each group.

This study demonstrated that 1.2 L of PEG-ASC and 2.0 L of PEG-ELS are clinically equivalent with respect to cleansing efficacy, including ADR. Furthermore, the 1.2 L PEG-ASC regimen was superior to the 2.0 L PEG-ELS regimen in terms of the required time for bowel preparation, palatability, and acceptability. These results support that combination of 1.2 L PEG-ASC solution and sennoside with prior low-residue diet is a suitable alternative to the standard bowel preparation with PEG-ELS in outpatients for afternoon colonoscopy.

We have to take the difference between the races and the region into consideration when we discuss the efficacy of bowel cleansing regimens. They can vary in effectiveness depending on the racial or regional groups because body dimensions, diet habits, and bowel transit time, etc., vary among population and are considered to affect the reactivity for cleansing agents. Although the efficacy of the combination of PEG-ASC lower than 2 L plus bisacodyl or sennoside was currently evaluated only in East Asia, they are thought to be effective in the population who are successfully treated with 2 L PEG-ELS plus laxative. In this point of view, further studies in various races and regions are required to confirm the efficacy of PEG-ASC lower than 2.0 L plus laxative.

We wish to acknowledge the help of Mr. Hideki Hayashi as a statistical consultant.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Jha AK, Madalinski M S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25540] [Article Influence: 1824.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 2. | Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87:159-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3455] [Cited by in RCA: 3345] [Article Influence: 115.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Short MW, Layton MC, Teer BN, Domagalski JE. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:93-100. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Winawer SJ, Zauber AG. The advanced adenoma as the primary target of screening. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:1-9, v. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O'Brien MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Hankey BF, Shi W, Bond JH, Schapiro M, Panish JF, Stewart ET, Waye JD. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1952] [Cited by in RCA: 2284] [Article Influence: 175.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, Lederle FA, Bond JH, Mandel JS, Church TR. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1106-1114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 552] [Cited by in RCA: 646] [Article Influence: 53.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Heresbach D, Barrioz T, Lapalus MG, Coumaros D, Bauret P, Potier P, Sautereau D, Boustière C, Grimaud JC, Barthélémy C, Sée J, Serraj I, D'Halluin PN, Branger B, Ponchon T. Miss rate for colorectal neoplastic polyps: a prospective multicenter study of back-to-back video colonoscopies. Endoscopy. 2008;40:284-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 370] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | van Rijn JC, Reitsma JB, Stoker J, Bossuyt PM, van Deventer SJ, Dekker E. Polyp miss rate determined by tandem colonoscopy: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:343-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 878] [Cited by in RCA: 917] [Article Influence: 48.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim NH, Jung YS, Jeong WS, Yang HJ, Park SK, Choi K, Park DI. Miss rate of colorectal neoplastic polyps and risk factors for missed polyps in consecutive colonoscopies. Intest Res. 2017;15:411-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lebwohl B, Kastrinos F, Glick M, Rosenbaum AJ, Wang T, Neugut AI. The impact of suboptimal bowel preparation on adenoma miss rates and the factors associated with early repeat colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1207-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cohen J, Grunwald D, Grossberg LB, Sawhney MS. The Effect of Right Colon Retroflexion on Adenoma Detection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:818-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chang JY, Moon CM, Lee HJ, Yang HJ, Jung Y, Kim SW, Jung SA, Byeon JS. Predictive factors for missed adenoma on repeat colonoscopy in patients with suboptimal bowel preparation on initial colonoscopy: A KASID multicenter study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sulz MC, Kröger A, Prakash M, Manser CN, Heinrich H, Misselwitz B. Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Bowel Preparation on Adenoma Detection: Early Adenomas Affected Stronger than Advanced Adenomas. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Lee TJ, Blanks RG, Rees CJ, Wright KC, Nickerson C, Moss SM, Chilton A, Goddard AF, Patnick J, McNally RJ, Rutter MD. Longer mean colonoscopy withdrawal time is associated with increased adenoma detection: evidence from the Bowel Cancer Screening Programme in England. Endoscopy. 2013;45:20-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Park JH, Kim SJ, Hyun JH, Han KS, Kim BC, Hong CW, Lee SJ, Sohn DK. Correlation Between Bowel Preparation and the Adenoma Detection Rate in Screening Colonoscopy. Ann Coloproctol. 2017;33:93-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:378-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 642] [Cited by in RCA: 700] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rex DK, Imperiale TF, Latinovich DR, Bratcher LL. Impact of bowel preparation on efficiency and cost of colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1696-1700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee HS, Byeon JS. Bowel preparation, the first step for a good quality colonoscopy. Intest Res. 2014;12:1-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Michael KA, DiPiro JT, Bowden TA, Tedesco FJ. Whole-bowel irrigation for mechanical colon cleansing. Clin Pharm. 1985;4:414-424. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Connor A, Tolan D, Hughes S, Carr N, Tomson C. Consensus guidelines for the safe prescription and administration of oral bowel-cleansing agents. Gut. 2012;61:1525-1532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Martel M, Barkun AN, Menard C, Restellini S, Kherad O, Vanasse A. Split-Dose Preparations Are Superior to Day-Before Bowel Cleansing Regimens: A Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:79-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kilgore TW, Abdinoor AA, Szary NM, Schowengerdt SW, Yust JB, Choudhary A, Matteson ML, Puli SR, Marshall JB, Bechtold ML. Bowel preparation with split-dose polyethylene glycol before colonoscopy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1240-1245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Enestvedt BK, Tofani C, Laine LA, Tierney A, Fennerty MB. 4-Liter split-dose polyethylene glycol is superior to other bowel preparations, based on systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1225-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pontone S, Angelini R, Standoli M, Patrizi G, Culasso F, Pontone P, Redler A. Low-volume plus ascorbic acid vs high-volume plus simethicone bowel preparation before colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4689-4695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Valiante F, Pontone S, Hassan C, Bellumat A, De Bona M, Zullo A, de Francesco V, De Boni M. A randomized controlled trial evaluating a new 2-L PEG solution plus ascorbic acid vs 4-L PEG for bowel cleansing prior to colonoscopy. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:224-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Ell C, Fischbach W, Bronisch HJ, Dertinger S, Layer P, Rünzi M, Schneider T, Kachel G, Grüger J, Köllinger M, Nagell W, Goerg KJ, Wanitschke R, Gruss HJ. Randomized trial of low-volume PEG solution versus standard PEG + electrolytes for bowel cleansing before colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:883-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ponchon T, Boustière C, Heresbach D, Hagege H, Tarrerias AL, Halphen M. A low-volume polyethylene glycol plus ascorbate solution for bowel cleansing prior to colonoscopy: the NORMO randomised clinical trial. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:820-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Xie Q, Chen L, Zhao F, Zhou X, Huang P, Zhang L, Zhou D, Wei J, Wang W, Zheng S. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of low-volume polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid versus standard-volume polyethylene glycol solution as bowel preparations for colonoscopy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tajika M, Tanaka T, Ishihara M, Mizuno N, Hara K, Hijioka S, Imaoka H, Sato T, Yogi T, Tsutsumi H, Fujiyoshi T, Hieda N, Okuno N, Yoshida T, Bhatia V, Yatabe Y, Yamao K, Niwa Y. A Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating a Low-Volume PEG Solution Plus Ascorbic Acid versus Standard PEG Solution in Bowel Preparation for Colonoscopy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:326581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tajika M, Tanaka T, Ishihara M, Hirayama Y, Oonishi S, Mizuno N, Hara K, Hijioka S, Imaoka H, Fujiyoshi T, Hieda N, Okuno N, Yoshida T, Yamao K, Bhatia V, Ando M, Niwa Y. Optimal intake of clear liquids during preparation for afternoon colonoscopy with low-volume polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E416-E423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kamei M, Shibuya T, Takahashi M, Makino M, Haga K, Nomura O, Murakami T, Ritsuno H, Ueyama H, Kodani T, Ishikawa D, Matsumoto K, Sakamoto N, Osada T, Ogihara T, Watanabe S, Nagahara A. Efficacy and Acceptability of 1 Liter of Polyethylene Glycol with Ascorbic Acid vs. 2 Liters of Polyethylene Glycol Plus Mosapride and Sennoside for Colonoscopy Preparation. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:523-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kang SH, Jeen YT, Lee JH, Yoo IK, Lee JM, Kim SH, Choi HS, Kim ES, Keum B, Lee HS, Chun HJ, Kim CD. Comparison of a split-dose bowel preparation with 2 liters of polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid and 1 liter of polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid and bisacodyl before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:343-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:620-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 930] [Cited by in RCA: 924] [Article Influence: 57.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Clark BT, Protiva P, Nagar A, Imaeda A, Ciarleglio MM, Deng Y, Laine L. Quantification of Adequate Bowel Preparation for Screening or Surveillance Colonoscopy in Men. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:396-405; quiz e14-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Levin TR. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:844-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1367] [Cited by in RCA: 1443] [Article Influence: 111.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kim MS, Park J, Park JH, Kim HJ, Jang HJ, Joo HR, Kim JY, Choi JH, Heo NY, Park SH, Kim TO, Yang SY. Does Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Plus Ascorbic Acid Induce More Mucosal Injuries than Split-Dose 4-L PEG during Bowel Preparation? Gut Liver. 2016;10:237-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Jha AK, Chaudhary M, Jha P, Kumar U, Dayal VM, Jha SK, Purkayastha S, Ranjan R, Mishra M, Sehrawat K. Polyethylene glycol plus bisacodyl: A safe, cheap, and effective regimen for colonoscopy in the South Asian patients. JGH Open. 2018;2:249-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Brahmania M, Ou G, Bressler B, Ko HK, Lam E, Telford J, Enns R. 2 L versus 4 L of PEG3350 + electrolytes for outpatient colonic preparation: a randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:408-416.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kwon JE, Lee JW, Im JP, Kim JW, Kim SH, Koh SJ, Kim BG, Lee KL, Kim SG, Kim JS, Jung HC. Comparable Efficacy of a 1-L PEG and Ascorbic Acid Solution Administered with Bisacodyl versus a 2-L PEG and Ascorbic Acid Solution for Colonoscopy Preparation: A Prospective, Randomized and Investigator-Blinded Trial. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Aranda-Hernández J, Hwang J, Kandel G. Seeing better--Evidence based recommendations on optimizing colonoscopy adenoma detection rate. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1767-1778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 41. | Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK, Lee JK, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, de Boer J, Fireman BH, Schottinger JE, Quinn VP, Ghai NR, Levin TR, Quesenberry CP. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1298-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1559] [Article Influence: 141.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Clark BT, Rustagi T, Laine L. What level of bowel prep quality requires early repeat colonoscopy: systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of preparation quality on adenoma detection rate. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1714-1723; quiz 1724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, Pike IM, Adler DG, Fennerty MB, Lieb JG 2nd, Park WG, Rizk MK, Sawhney MS, Shaheen NJ, Wani S, Weinberg DS. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:31-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 649] [Cited by in RCA: 836] [Article Influence: 83.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kim TK, Kim HW, Kim SJ, Ha JK, Jang HH, Hong YM, Park SB, Choi CW, Kang DH. Importance of the time interval between bowel preparation and colonoscopy in determining the quality of bowel preparation for full-dose polyethylene glycol preparation. Gut Liver. 2014;8:625-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Fujita I, Akagi Y, Hirano J, Nakanishi T, Itoh N, Muto N, Tanaka K. Distinct mechanisms of transport of ascorbic acid and dehydroascorbic acid in intestinal epithelial cells (IEC-6). Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 2000;107:219-231. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 46. | Lichtenstein GR, Cohen LB, Uribarri J. Review article: Bowel preparation for colonoscopy--the importance of adequate hydration. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:633-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Ayus JC, Levine R, Arieff AI. Fatal dysnatraemia caused by elective colonoscopy. BMJ. 2003;326:382-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Markowitz GS, Stokes MB, Radhakrishnan J, D'Agati VD. Acute phosphate nephropathy following oral sodium phosphate bowel purgative: an underrecognized cause of chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3389-3396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |