Published online Dec 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i23.4020

Peer-review started: September 3, 2019

First decision: September 23, 2019

Revised: October 19, 2019

Accepted: November 23, 2019

Article in press: November 23, 2019

Published online: December 6, 2019

Processing time: 93 Days and 14 Hours

Parahiatal hernias (PHHs) are rare occurring disease, with a reported incidence of 0.2%-0.35% in patients undergoing surgery for hiatal hernia. We found only a handful of cases of primary PHHs in the literature. The aim of this paper is to present a case of a primary PHH and perform a systematic review of the literature.

We report the case of a 60-year-old Caucasian woman with no history of thoraco-abdominal surgery or trauma, which accused epigastric pain, starting 2 years prior, pseudo-angina and bloating. Based on imagistic findings the patient was diagnosed with a PHH and an associated type I hiatal hernia. Patient underwent laparoscopic surgery and we found an opening in the diaphragm of 7 cm diameter, lateral to the left crus, through which 40%-50% of the stomach had herniated in the thorax, and a small sliding hiatal hernia with an anatomically intact hiatal orifice but slightly enlarged. We performed closure of the defect, suture hiatoplasty and a “floppy” Nissen fundoplication. Postoperative outcome was uneventful, with the patient discharged on the fifth postoperative day. We performed a review of the literature and identified eight articles regarding primary PHH. All data was compiled into one tabled and analyzed.

Primary PHHs are rare entities, with similar clinical and imagistic findings with paraesophageal hernias. Treatment usually includes laparoscopic approach with closure of the defect and the esophageal hiatus should be dissected and analyzed. Postoperative outcome is favorable in all cases reviewed and no recurrence is cited in the literature.

Core tip: We present the management of a case with primary parahiatal hernia associated with type I hiatal hernia, from the imagistic findings that led us to the preoperative diagnosis to its surgical treatment. We also performed a review of the literature, which emphasizes the uniqueness and rarity of this disease. Frequently, the presentation is in an acute setting with the most cited complications being incarceration/perforation of the stomach and mezenteroaxial volvulus. Treatment includes closure of the defect and postoperative outcome is favorable in all cases we reviewed, with no cited recurrence.

- Citation: Preda SD, Pătraşcu Ș, Ungureanu BS, Cristian D, Bințințan V, Nica CM, Calu V, Strâmbu V, Sapalidis K, Șurlin VM. Primary parahiatal hernias: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(23): 4020-4028

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i23/4020.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i23.4020

Parahiatal hernia (PHH) represents a type of diaphragmatic hernia in which a herniation occurs through a defect in the diaphragm, adjacent to an anatomically intact esophageal hiatus. Its incidence is very rare, only a small number of cases being reported in the literature so far.

Because of its close relation to the hiatus, similar symptom presentation, imagistic findings and treatment, most authors include this type of diaphragmatic hernia with hiatal hernia, while other authors consider them as a rare variant of paraesophageal hernias[1]. From an ethiopathogenic standpoint, PHHs can be classified as either primary or secondary to a surgical intervention that involved the hiatal orifice as in esophagectomies, esogastrectomies, Heller myotomy, or any other intervention that involves manipulation of the hiatus.

We performed a search on PubMed using the keywords “parahiatal” and “hernia” and after exclusion of irrelevant cases and cases of secondary PHHs, eight articles remained. Patient data from all eight articles were compiled into a table and analyzed.

To our knowledge, this is the first case of a preoperative diagnosed primary PHH associated with a type I hiatal hernia.

A 60-year-old Caucasian female patient was consulted and admitted in the Gastroenterology Department, after complaining of epigastric pain referred along the left costal margin and postprandial fullness that worsened in the last couple of weeks.

The symptoms started 2 years prior, initially the pain occurred without any triggering factor, but in the past 7 mo, it became progressively more frequent, more intense and more likely postprandial. Occasionally, it would be like an angina with left shoulder irradiation. The patient mentioned bloating in the epigastrium and the left hypochondrium calmed by eructation and she also described pyrosis for at least 5-6 mo.

Her personal medical records indicated a primary arterial hypertension grade II well controlled by medication, dyslipidemia under medication, right hip luxation (surgically treated) at the age of 9 and coxarthrosis. There were no other surgical interventions abdominal or thoracic, nor any traumatic history. Modified Visick score for acid reflux was 3.

She had a familial history of arterial hypertension. Smoking was denied, alcohol consumption occasionally, she preferred carbonated drinks.

Physical examination was not relevant, showing only a palpatory mild pain in the epigastrium and left hypochondrium, inferior liver margin at 1-2 cm below the ribs costal margin, no other peculiar findings.

Complete blood count, liver and renal functions within normal parameters.

Abdominal ultrasound indicated a mild hepatomegaly with steatosis, and small renal parapyelic cysts.

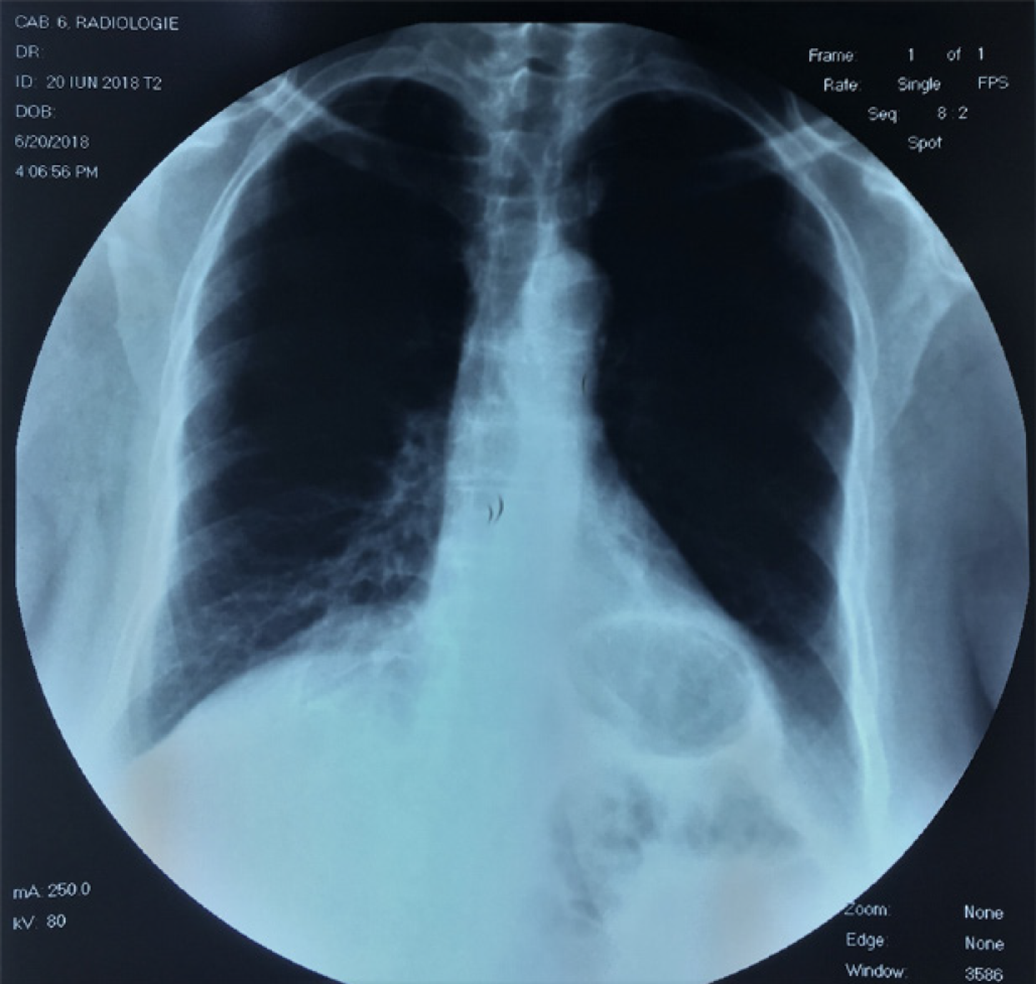

Chest X-Ray remarked the herniated stomach as a round-oval transparency located retrocardiac of 3.8/2.6 cm (Figure 1).

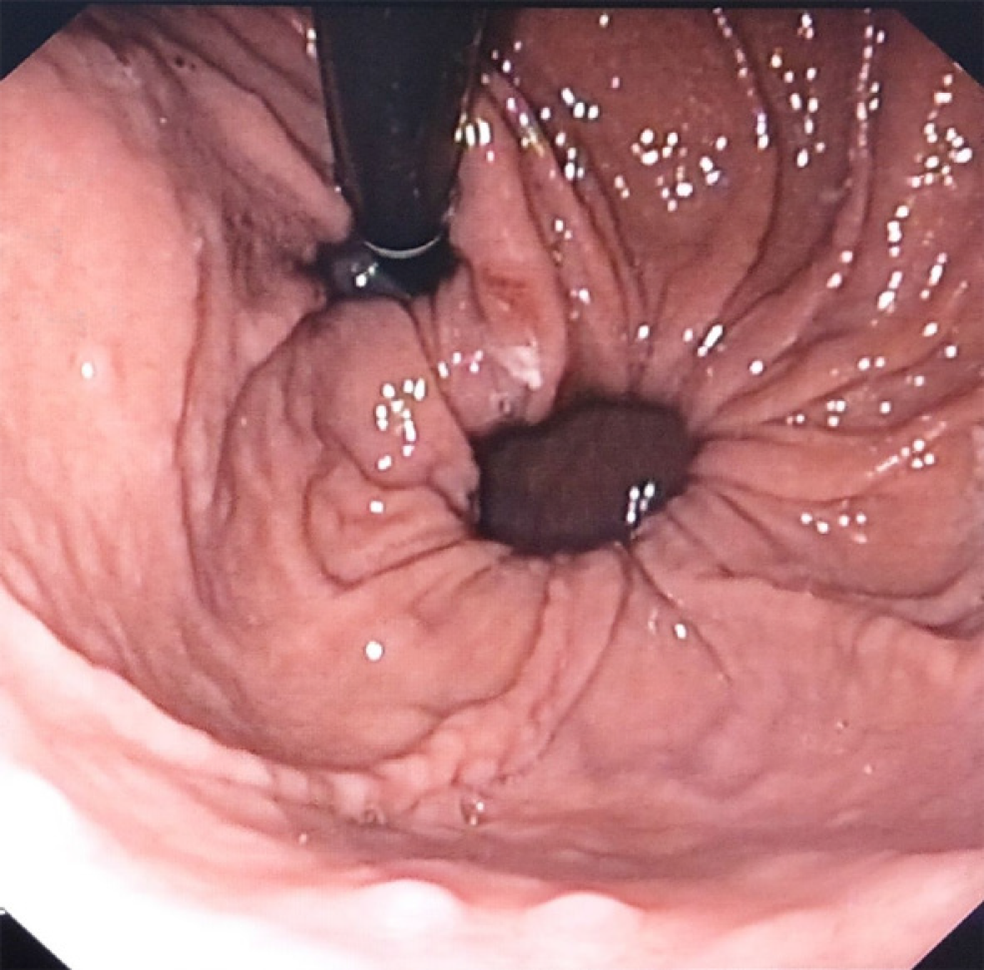

Upper digestive endoscopy showed normal esophageal mucosa and a small sliding hiatal hernia. In retroversion, a herniation of about 1/3 of the stomach could be seen through a separate opening in the diaphragm lateral to the cardia (Figure 2). This was interpreted as such, because of the circular shaped openings: one the hiatus and the other the diaphragmatic defect, which allowed the stomach to herniate. Between the two openings, a narrow band of tissue existed, which was interpreted as the left crus.

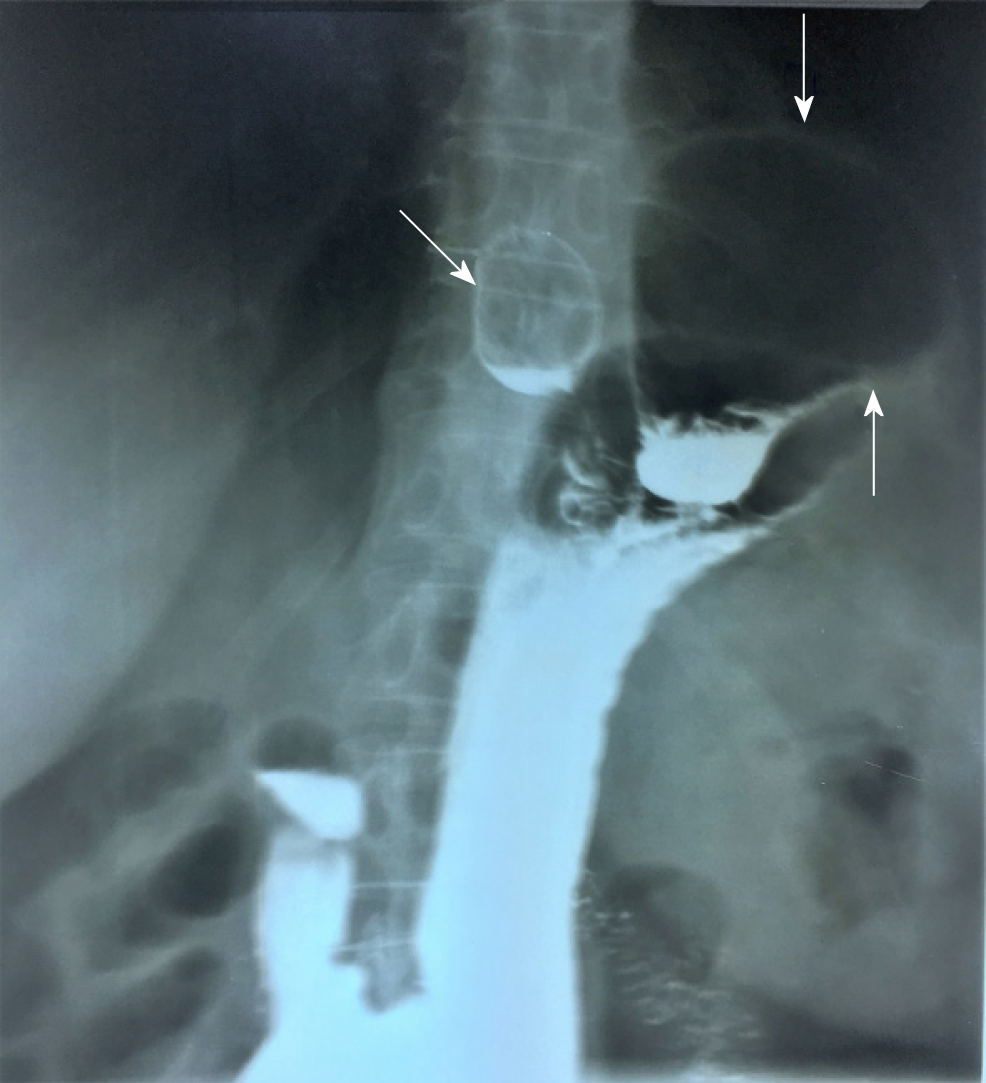

Diagnosis of PHH was confirmed by the upper gastrointestinal barium series, showing a small sliding hiatal hernia located medially and a large diaphragmatic hernia, located laterally, with the upper pole of the stomach above the diaphragm and a posterior volvulus of the gastric fundus in the mesenterial plane. Stasis was remarked in the gastric fundus, the rest of the stomach and duodenum were normal both in endoscopy and contrast radiology (Figure 3).

A diagnosis of primary PHH associated with small sliding hiatal hernia was set. Based upon the risk of complication and impact on the quality of life, the indication for surgery was set.

Preoperative preparation started with nil per os from the evening before the surgery, prophylactic administration of a single dose of low molecular weight heparin (0.4 mL of nadroparine administered subcutaneous) 8 h before surgery, American Society of Anesthesiologists grade II. The positioning on the operating table was identical with the approach of a hiatal hernia with the patient in dorsal decubitus, legs apart, both arms across the table, support for legs. Insufflation was done in the Palmer point and pressure set for 11 mmHg. We used 5 trocars, 10 mm for the optic, above the umbilicus, slightly left of the midline, 1/3 of the distance between umbilicus and xyphoid. A 5 mm trocar in the right hypochondrium, on the mid-axillary line, a 5 mm trocar in the epigastrium at the left of the xyphoid, a 10 mm trocar on the mid-axillary right line symmetrical to that on the left and a 5 mm trocar in the left flank on the anterior axillary line. The surgeon position between the legs of the patient, camera assistant at the left of the surgeon, first assistant to the right of the patient and second assistant to the left of the patient. The table was set in a reverse Trendelenburg position of 35%.

Inspection of the abdominal cavity did not reveal any particular findings, the left lobe of the liver was elevated with an aspiration cannula introduced through xyphoid trocar, and the hiatal orifice exposed. Initially we noticed a herniation of the upper 1/2 - 2/3rds of the stomach, but after it was reduced we could identify an opening in the diaphragm, located left of the hiatal orifice, near the left crus. It was elliptic in shape, anteroposterior long axis, its dimensions were estimated at 7/4 cm (Figure 4). The dissection of the hernia sac was the first step of the intervention, careful use of sharp dissection with hook or scissors was necessary to avoid damage of the pleura that was intimately adherent. During dissection, a small 2 cm breach in the pleura occurred, with no cardiorespiratory events. The breach was sutured with inflation of the lung when tying the last knot. After complete liberation, the sac was excised and the hiatal orifice was dissected and inspected, and revealed a small sliding hernia with a slightly enlarged hiatal orifice most probably responsible for the pyrosis accused by the patient (Figure 5).

A typical dissection of the esogastric junction and hiatal orifice was performed as in Nissen procedure. Decision was to close the parahiatal orifice with non-absorbable material, closure was possible without any tension. An overlying mesh was considered inappropriate because of the lack of tension and long-term risk of esophageal erosion. We decided to close the hiatal orifice posterior to the esophagus, which was intubated with a 36 Fr Faucher-type tube, and performed a 360° “floppy” Nissen fundoplication after mobilization of the gastric fundus from the gastrosplenic ligament using a vascular sealing device. The intervention lasted for 150 min. There were no adverse cardiopulmonary events during surgery or after waking up from anesthesia.

Chest X-ray taken after 24 h revealed a minimal pleural effusion, which was evacuated by thoracentesis.

Postoperative course was uneventful, full mobilization of the patient was possible from the 2nd postoperative day, early resumption of oral diet started progressively with clear liquids as in a usual postoperative diet after Nissen fundoplication. Discharge took place in the fourth postoperative day, the patient was seen in consultation as an outpatient after 2 wk, at 1 mo, 3 mo, 6 mo and at 12 mo postoperatively. Upper gastrointestinal barium series taken at 6 wk postoperative revealed no anatomical recurrence. Quality of life improved significantly, the degree of satisfaction of the patient was very high, Visick modified score for acid reflux of 1.

The aim of this review was to gather all of the published cases and perform a statistical descriptive analysis to identify the most important aspects related to diagnosis and treatment of primary PHH.

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines for reporting systematic reviews, we performed a search on PubMed, using the keywords “Parahiatal” and “hernia” and identified 28 articles, and we found an additional record through other sources. After exclusion of articles that contained no information on patients with PHH and exclusion of articles with no abstract or full text, 26 articles remained. Then, after assessing full text articles, we excluded the following articles: 9 Articles containing secondary PHH; 2 articles of PHH in children; 2 articles that were written in Japanese; 1 article of incidental PHH in cadavers; and 2 articles not referring to PHH. Finally, only eight articles remained.

All data was compiled into one table and the result is a study on 14 patients (including ours) with primary PHHs. We assessed gender, age, presentation symptoms, moment of diagnosis, defect size, if the PHH had any associated complications, intraoperative incidents, treatment, postoperative course, and follow-up (Table 1).

| Ref. | Case No. | Gender | Age (yr) | Symptoms | Diagnosis | Defect size (cm) | Associated complication | Treatment | Associated hiatal hernia | Fundoplication | Intraop incidents | Postop course | Postop discharge | Follow-up (mo) |

| Demmy et al[2], 1994 | 1 | F | 48 | Upper abdominal pain; shortness of breath; cough | Intraop | 2 | gastric necrosis andperforation | closure; decortication of left pleura; left pleural drainage; | ND | No | ND | sepsis; subpulmonic empyema | 42 | ND |

| Rodefeld et al[9], 1998 | 2 | F | 64 | Epigastric pain; heartburn; regurgitation; weight loss | Intraop | 5 | gastric incarceration | closure; suture hiatoplasty; gastropexy | ND | Yes | gastric full thickness tear | subcutaneous emphysema | 3 | 15 |

| Scheidler et al[6], 2002 | 3 | F | 68 | Nausea; emesis; regurgitation; reflux disease; epigastric pain | Intraop | ND | No | closuresuture hiatoplasty; gastropexy | No | Yes | None | uneventful | 2 | 12 |

| 4 | M | 57 | Postprandial chest pain | Intraop | ND | No | ND | ND | ND | None | uneventful | ND | 48 | |

| Ohtsuka et al[4], 2012 | 5 | M | 39 | Epigastric pain; nausea; vomiting | Postop | 5 | colic and gastric incarceration | closure | No | No | ND | uneventful | ND | ND |

| Palanivelu et al[8], 2008 | 10 | M | 32 | ND | Intraop | 8 | No | closure; hiatoplasty; mesh reinforce | ND | No | ND | ND | ND | 6 |

| 11 | M | 55 | ND | Intraop | 18 | No | closure; hiatoplasty; mesh reinforce | ND | No | ND | ND | ND | 6 | |

| 12 | M | 29 | ND | Intraop | 30 | No | closure; hiatoplasty; mesh reinforce | Yes | Yes | ND | ND | ND | 6 | |

| 13 | M | 65 | ND | Intraop | 16 | No | closure; hiatoplasty; mesh reinforce | Yes | Yes | ND | ND | ND | 6 | |

| Lew et al[1], 2013 | 6 | F | 51 | Epigastric pain; vomiting; heartburn; early satiety | Intraop | 3 | mezenteroaxial gastric volvulus | mesh repair | No | Yes | None | uneventful | 5 | 7 |

| Staerkle et al[5], 2016 | 7 | M | 71 | Chest pain; foregut obstruction; dyspneea | Intraop | ND | No | closure; suture hiatoplasty; mesh reinforce | Yes | Yes | None | uneventful | 3 | 24 |

| Koh et al[7], 2016 | 8 | F | 40 | Epigastric pain; anemia | Intraop | 5 | mezenteroaxial gastric volvulus | closure | ND | No | ND | uneventful | 2 | ND |

| 9 | F | 51 | Epigastric pain | Intraop | 3 | mezenteroaxial gastric volvulus | closure; mesh reinforce | ND | Yes | ND | uneventful | 5 | ND | |

| Our study | 14 | F | 60 | Epigastric pain; reffered pain; pseudoangina; reflux | Preop | 7 | No | Closure; suture hiatoplasty | Yes | Yes | left pleural breach | uneventful | 5 | 12 |

As seen in the table, we were not able to collect all the data according to our objective because in some cases there were no mentions in the description.

The gender distribution was equal 1:1 (7/7). The average age at diagnosis was 52 years ± 13 years, range between 29 and 71 years old.

The most prevalent symptoms were epigastric pain, vomiting, nausea and chest pain, but other symptoms that could appear are: upper abdominal pain, dyspnea, coughing, heartburn, regurgitation, weight loss, dysphagia, anemia, back pain and retching.

In most of the cases, 12 out of 14 cases (85.71%), the diagnosis was made intraoperatively. In one case (7.14%) the diagnosis was made postoperatively and in only 1 case the diagnosis was made preoperative (7.14%).

Average defect size was 9.27 ± 8.62 cm, with a minimum of 2 cm, maximum of 30 cm and a median of 5 cm.

Complication arose in 6 out of 14 patients (42.85%) as detailed: (1) Gastric necrosis and perforation (16.66%); (2) gastric incarceration (33.33%) (one had colic incarceration associated); and (3) mezenteroaxial gastric volvulus (50%).

Treatment was closure of the defect in 6 cases (46.15%), closure of the defect with mesh reinforce in 6 cases (46.15%), mesh repair in 1 case (7.69%).

Intraoperative incidents that were reported are gastric tear (1 case) and left pleural breach (1 case).

Average postoperative discharge was 8.3 ± 12.76 d, with a minimum of 2 d, maximum of 42 d, median of 4 d, and mode of 5 d.

Average follow-up was 14.2 ± 12.52 mo with a minimum of 5 mo and maximum of 48 mo.

PHHs could be primary or secondary. Secondary PHHs occur after alterations of the hiatal orifice after interventions upon gastroesophageal junction, Heller myotomy, esophagectomies or esogastrectomies. Primary PHHs are very rare, their existence in the past was even put to question[2]. It has been postulated that they occur due to a closing failure of the embryonic pleuroperitoneal canal[3,4].

Due to its identical clinical presentation with hiatal hernias, subtle differences in imaging, we have not found any case of a primary PHH diagnosed preoperative, except ours.

The array of symptoms it can cause is wide, making it almost impossible to suspect clinically[1,4,5].

Imagistic can make the diagnosis but the details are subtle, and without knowledge of this disease, the diagnosis can be often incorrect. In our case, the diagnosis was suspected during upper endoscopy and confirmed after barium contrast esogastrography[6].

The difference between PHHs and paraesophageal hernias in upper endoscopy was that the herniation occurred through a defect that appeared to be separated from the hiatus by the crus, creating 2 circular shapes (one the hiatus and the other the defect) with a thin but noticeable band of tissue between them. At the upper gastrointestinal barium series, the existence of a gap (band of tissue) between the sliding hernia and the herniated stomach, creating the appearance of two sacs (one medially and one lateral), led us to this diagnosis.

Their incidence is difficult to assess, a total number of 14 cases were reported in the literature. There are only 2 series of patients that can point toward the incidence of this disease: One reported by Koh et al[7] with 2 cases met in 914 consecutives cases of hiatal hernia repairs, an incidence of nearly 0.2% and 0.35% reported by Palanivelu et al[8] with 4 cases met in 1127 patients with hiatal hernia who underwent surgery.

Imagistic can make the diagnosis but the details are subtle, and without knowledge of this disease the diagnosis can be often incorrect[6].

If the diagnosis is missed by the preoperative imagery, it is discovered during surgery, a surgeon that usually addresses hiatal hernias in his practice should always bear in mind this possibility.

A common complication of PHHs is the risk of volvulus of the stomach due to a fixed gastroesophageal junction and a rising gastric body in the sac.

Laparoscopic approach is preferred by the majority of authors. The port placement is similar with hiatal surgery.

The surgical attitude towards the defect is primary closure with suture. The closure of the defect should be done using tension-free sutures[9]. Regarding mesh reinforcement, it was added in 7 cases out of 14 analyzed in our review. Some authors report a fibrous ring around the defect that make its closure difficult with just sutures, and thus a mesh can be added to reinforce the closure or a mesh repair can be performed[1,7,8].

Unlike hiatal hernias, the use of mesh in these cases can hypothetically be done without the risks that mesh hiatoplasty implies, as the mesh does not sit in contact with the esophagus. We suggest using glue or sutures for mesh fixation and not tacks due to the risks for pericardial injury. In lack of more data to support the mesh, we cannot make any recommendation about its use.

We believe the esophageal hiatus should always be dissected as closure of the defect will put the esophageal hiatus under tension and it can cause it to enlarge. If the orifice is enlarged, hiatoplasty becomes mandatory. Hiatoplasty was performed in half of the cases we reviewed.

Fundoplication should not be performed routinely, but only when concomitant acid reflux or hiatus hernia exists[7]. We chose, however to perform a floppy Nissen because the patient had specific complaints and a small sliding hiatal hernia was evident intraoperatively.

Postoperative course is not different from that of an operated paraesophageal hiatal hernia and should include early mobilization, avoidance of any physical effort and early oral intake resumption with diet progressing from clear liquids to solids over a period of several weeks if fundoplication has been added. Postoperative outcome is usually favorable, with no recurrence cited in the literature so far.

Primary PHHs are rare entities, with a small incidence, very similar clinical and imagistic findings with paraesophageal hernias. It is diagnosed more frequently intraoperatively and treatment consists of repair by simple closure. Whenever tension is present in the suture line, a mesh reinforcement could be used. Calibration of the hiatal orifice is mandatory especially in cases where suture exacts tension on the hiatus, whenever an associated hiatal hernia or refractory reflux is present.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Romania

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Wang J S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Lew PS, Wong AS. Laparoscopic mesh repair of parahiatal hernia: a case report. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2013;6:231-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Demmy TL, Boley TM, Curtis JJ. Strangulated parahiatal hernia: not just another paraesophageal hernia. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58:226-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | MacDougall JT. Herniation though congenital diaphragmatic defects in adults. Can J Surg. 1963;6:301-305. |

| 4. | Ohtsuka H, Imamura K, Adachi K. An unusual diaphragmatic hernia. Parahiatal hernia. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1420-1623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Staerkle RF, Skipworth RJE, Leibman S, Smith GS. Emergency laparoscopic mesh repair of parahiatal hernia. ANZ J Surg. 2018;88:E564-E565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Scheidler MG, Keenan RJ, Maley RH, Wiechmann RJ, Fowler D, Landreneau RJ. "True" parahiatal hernia: a rare entity radiologic presentation and clinical management. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:416-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Koh YX, Ong LW, Lee J, Wong AS. Para-oesophageal and parahiatal hernias in an Asian acute care tertiary hospital: an underappreciated surgical condition. Singapore Med J. 2016;57:669-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Jategaonkar PA, Parthasarathi R, Balu K. Laparoscopic repair of parahiatal hernias with mesh: a retrospective study. Hernia. 2008;12:521-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rodefeld MD, Soper NJ. Parahiatal hernia with volvulus and incarceration: laparoscopic repair of a rare defect. J Gastrointest Surg. 1998;2:193-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |