Published online Aug 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2341

Peer-review started: February 26, 2019

First decision: June 19, 2019

Revised: June 21, 2019

Accepted: July 20, 2019

Article in press: July 20,2019

Published online: August 26, 2019

Processing time: 183 Days and 12.5 Hours

Due to some similarities in the manifestations between central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC) and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV), PCV may be misdiagnosed as CSC. More attention should be paid to distinguishing these two disorders.

A 52-year-old woman presented to our hospital with blurred vision in her left eye for approximately 1 wk. Anterior segment and intraocular pressure findings were normal in both eyes. Fundus photography of the left eye showed a seemingly normal adult oculus fundus without any obvious hard exudate or hemorrhage. Optical coherence tomography exhibited a hypo-reflective space beneath both the neurosensory retina and the pigment epithelium layer. The late phase of fluorescein angiography revealed increased leakage. The patient was initially diagnosed with CSC. At follow-up, however, the final diagnosis turned out to be PCV.

CSC and PCV are two different retinal entities. Lipid deposition and hemorrhage are the most important elements that lead to confusion between these two entities. Indocyanine green angiography should be performed to make a definitive diagnosis, especially in cases with suspected PCV.

Core tip: Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and central serous chorioretinopathy are different diseases. While relatively mature research has been done on central serous chorioretinopathy, there is no unified understanding of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. These two diseases have some common symptoms, which have been plaguing clinicians. This case report provides a good example for the differential diagnosis between them. It also provides an alternative treatment for the clinical treatment of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.

- Citation: Wang TY, Wan ZQ, Peng Q. A patient misdiagnosed with central serous chorioretinopathy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(16): 2341-2345

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i16/2341.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2341

The clinical manifestations of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV) have been recognized for nearly two decades[1,2]. The clinical features of PCV include serosanguineous pigment epithelial detachment, recurrent sub-retinal hemorrhage, serous retinal detachment and sub-retinal exudation. Although PCV and central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC) are two different diseases, they have common characteristics[3]. PCV is often characterized by the presence of orange-red sub-retinal nodules and aneurysmal polypoidal lesions in the choroidal vasculature, with or without an associated branch vascular network. We report a patient with serous retinal detachments masquerading as CSC.

A 52-year-old female presented to our hospital with blurred vision in her left eye for approximately 1 wk.

The patient reported no headache or eye pain. She had no other diseases.

Unremarkable.

No abnormalities were found on slit lamp examination.

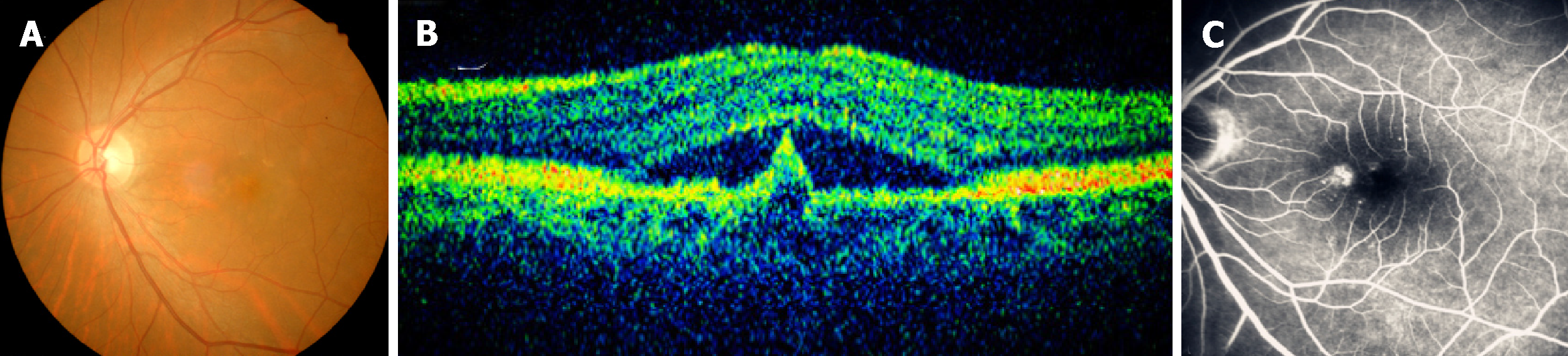

The patient underwent a comprehensive ophthalmic examination, including decimal best corrected visual acuity, color fundus photography, spectral domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) and fluorescein fundus angiography. On first examination, her best corrected visual acuity was 20/40 in the left eye and 20/20 in the right eye. Anterior segment and intraocular pressure findings were normal in both eyes. Fundus photography of the left eye showed a seemingly normal adult oculus fundus without any obvious hard exudate or hemorrhage (Figure 1A). OCT demonstrated a hypo-reflective space beneath both the neurosensory retina and the pigment epithelium layer (Figure 1B). The late phase of fluorescein angiography revealed hyper fluorescence (Figure 1C). On the basis of these findings, a diagnosis of CSC was made. As the patient lived thousands of miles from Shanghai and did not perceive obvious changes in her eyes, she declined follow-up visits to the hospital.

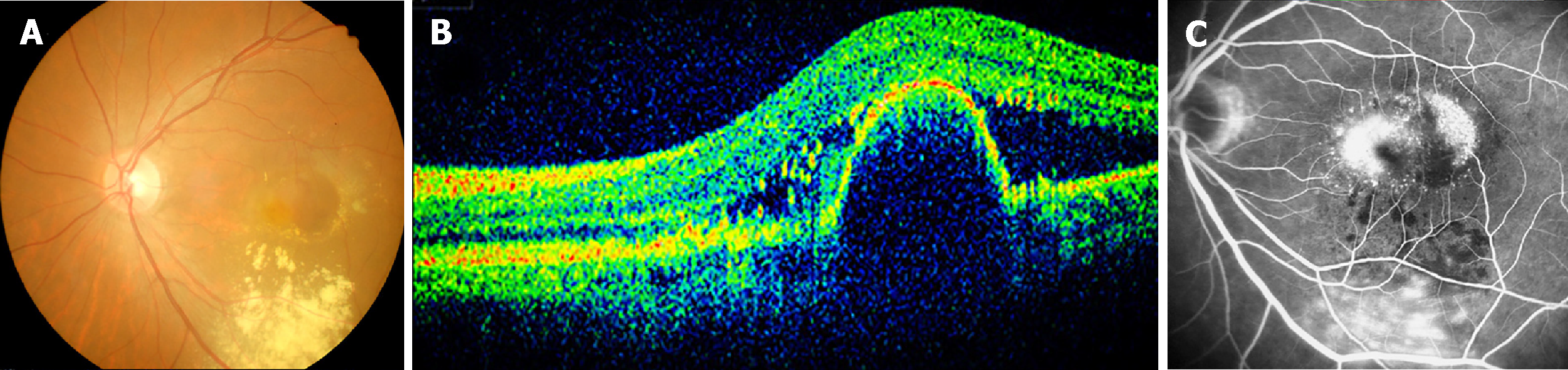

One month later, her visual acuity deteriorated suddenly. On examination, her best corrected visual acuity in the left eye was 20/100. A sub-retinal hemorrhage, hard exudate and reddish-orange nodules were found on fundus photography (Figure 2A). OCT demonstrated a pigment epithelium detachment and sub-retinal fluid (Figure 2B). The late phase of fluorescein angiography revealed increased hyper-fluorescence compared to that observed one year previously (Figure 2C). These characteristics led to the diagnosis of PCV.

Diagnosed as PCV.

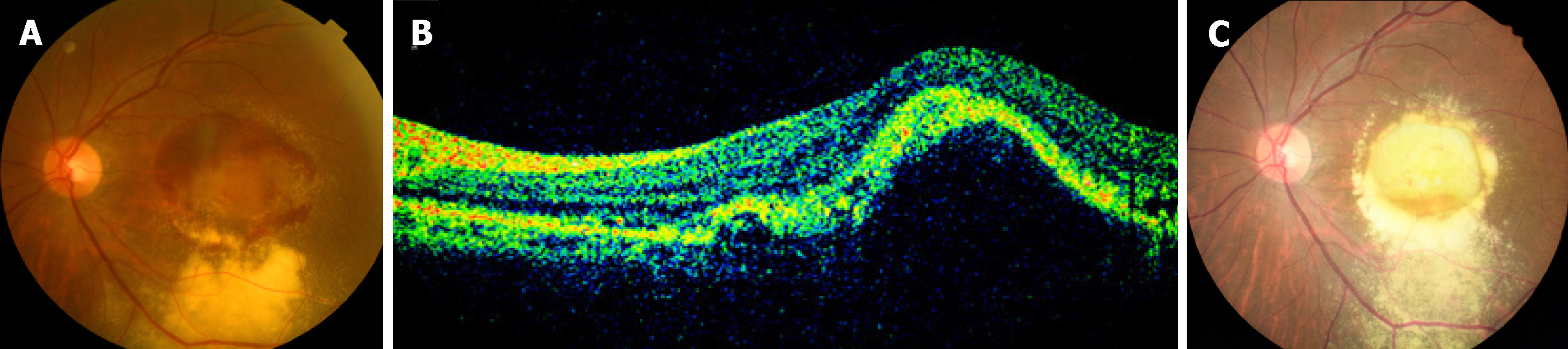

Most studies have shown that anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy may result in visual stabilization and a promising outcome in patients with PCV. Our patient received three monthly loading doses of intravitreal ranibizumab, which were injected 4 mm posterior to the corneal limbus into the vitreous cavity. During the follow-up period, her vision did not worsen. However, 6 mo later, the patient again complained of blurred vision, and fundus photography showed that there was an obvious sub-retinal hemorrhage at the posterior pole (Figure 3A). OCT demonstrated a pigment epithelium detachment (Figure 3B). Considering that this patient had received three intravitreal injections of ranibizumab at monthly intervals, three monthly intravitreal injections of conbercept were administered. Since then, the patient’s vision has been stable. As a new antiangiogenic agent, conbercept is a novel VEGF receptor fusion protein that blocks all isoforms of VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C and placenta growth factor (also known as PIGF). In addition, it has a higher binding affinity to VEGF. Six months after the first intravitreal injection of conbercept, fundus photography showed no recurrence of hemorrhage (Figure 3C). Her visual acuity was 40/300 in the left eye, which was not improved. The patient showed no change in her eye condition during the continuous follow-up.

PCV was once regarded as a variant of wet age-related macular degeneration. We now realize that it may also manifest with serous retinal detachments masquerading as CSC, and PCV patients often present with several unique clinical features that are obviously different from typical neovascular age-related macular degeneration[4-6]. PCV has been defined as “the presence of single or multiple focal areas of hyper-fluorescence arising from the choroidal circulation within the first 6 min after the injection of indocyanine green (ICG), with or without an associated branch vascular network. The presence of orange-red sub-retinal nodules with corresponding ICG hyperfluorescence is pathognomonic of PCV.” CSC is characterized by a serous retinal detachment in the posterior fundus accompanied by several leaks at the retinal pigment epithelium. It often has a favorable visual prognosis, with the resolution of sensory retinal detachment after several months[7,8]. The classic manifestations of PCV and CSC made it difficult to differentiate them from each other. It is important to make a distinction between these two entities, because they are different in their natural course, response to treatment and visual prognosis[9]. Fundus photography is crucial in the diagnosis and management of PCV and CSC, but ICG angiography (ICGA) is regarded as the gold standard for the diagnosis of PCV. OCT provides complementary information on the structure of the retina observed on ICGA[10].

ICGA is seldom used when PCV shows a focal macular detachment with one or more small pigment epithelial detachments. Because these clinical presentations are so similar, this type of disease is frequently diagnosed as CSC. However, as far as chronic CSC is concerned, it may also be associated with intra-retinal lipid deposition accumulation. In addition, sub-retinal hemorrhage and choroidal neovascularization are also possible complications of CSC, while PCV is characterized by lipid deposition and hemorrhage. In view of these findings, when neurosensory detachment in CSC is associated with lipid deposition or hemorrhage, both fluorescein fundus angiography and ICGA should be performed to make a definitive diagnosis. Certain demographic and clinical features can also help to distinguish PCV from CSC. PCV mainly occurs in middle-aged to elderly subjects, and most generally affects patients in their 50s or 60s, while the young are more prone to CSC. Most importantly, when the fundus photography of a patient with PCV shows dot hemorrhagic lesions, ICGA will show dot hyper-fluorescence corresponding to the hemorrhagic lesions in the early phase of angiography. In contrast, the CSC lesion is hyperfluorescent only 5 min after performing ICGA.

CSC and PCV are two different retinal entities. ICGA is essential in the diagnosis of PCV, and should be performed to make a definitive diagnosis, especially in patients with suspected PCV. Lipid deposition and hemorrhage are the most important elements that lead to confusion between these two entities. When CSC is associated with lipid deposition or sub-retinal hemorrhage, we should always bear in mind that ICGA may help to distinguish between CSC and PCV.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tekin K S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Zhou BX

| 1. | Ozawa S, Ishikawa K, Ito Y, Nishihara H, Yamakoshi T, Hatta Y, Terasaki H. Differences in macular morphology between polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and exudative age-related macular degeneration detected by optical coherence tomography. Retina. 2009;29:793-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wen F, Chen C, Wu D, Li H. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in elderly Chinese patients. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:625-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yannuzzi LA, Slakter JS, Kaufman SR, Gupta K. Laser treatment of diffuse retinal pigment epitheliopathy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1992;2:103-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yannuzzi LA, Sorenson J, Spaide RF, Lipson B. Idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (IPCV). 1990. Retina. 2012;32 Suppl 1:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yang LH, Jonas JB, Wei WB. Optical coherence tomographic enhanced depth imaging of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Retina. 2013;33:1584-1589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wong CW, Yanagi Y, Lee WK, Ogura Y, Yeo I, Wong TY, Cheung CMG. Age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in Asians. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2016;53:107-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Levine R, Brucker AJ, Robinson F. Long-term follow-up of idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy by fluorescein angiography. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:854-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Imamura Y, Fujiwara T, Spaide RF. Fundus autofluorescence and visual acuity in central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:700-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yannuzzi LA, Freund KB, Goldbaum M, Scassellati-Sforzolini B, Guyer DR, Spaide RF, Maberley D, Wong DW, Slakter JS, Sorenson JA, Fisher YL, Orlock DA. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy masquerading as central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:767-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kawamura A, Yuzawa M, Mori R, Haruyama M, Tanaka K. Indocyanine green angiographic and optical coherence tomographic findings support classification of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy into two types. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91:e474-e481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |