Published online Jan 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i1.19

Peer-review started: October 31, 2018

First decision: November 28, 2018

Revised: December 4, 2018

Accepted: December 21, 2018

Article in press: December 21, 2018

Published online: January 6, 2019

Processing time: 68 Days and 14.8 Hours

Contrast enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasound (CEH-EUS) is a spreading technique; some studies have shown its value in the diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma using quantitative analysis.

To examine the value of CEH-EUS for differentiating various pancreatic lesions in everyday routine with qualitative and quantitative analysis.

Data of 55 patients with pancreatic lesions who underwent CEH-EUS were analysed retrospectively. Perfusion characteristics were classified by the investigator qualitatively immediately upon investigation, quantitative analysis was performed later on. Samples from fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) or surgical specimen served as gold standard.

CEH-EUS showed 39 hypoenhanced lesions, 3 non-enhanced and 13 hyperenhanced lesions. Concordance of the investigators qualitative classification of peak contrast enhancement with quantitative analysis later on was 100%, while other parameters such as arrival time, time to peak or area under the curve did not show additional value. 34 of 39 hypoenhanced lesions were pancreatic adenocarcinoma; of the hyperenhanced lesions 4 were inflammatory, 3 neuroendocrine carcinomas, 1 lymphoma, 1 insulinoma and 4 metastases (2 of renal cell carcinoma, 2 of lung cancer). Non-enhanced lesions showed up as necroses. Sensitivity for the detection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma was 100%, specificity 87.2% for hypoenhancement alone; in otherwise healthy pancreatic tissue all hypoenhanced lesions were pancreatic adenocarcinoma (sensitivity and specificity 100%, PPV and NPV for adenocarcinoma 100%).

This study again shows the excellent value of CEH-EUS in everyday routine for diagnostics of various focal pancreatic lesions suggesting that qualitatively assessed hypoenhancement is highly predictive for adenocarcinoma. Additional quantitative analysis of perfusion parameters does not add diagnostic yield. In case of the various hyperenhanced pancreatic lesions in our data set, histologic sampling is essential for further treatment.

Core tip: In the diagnostic of focal pancreatic lesions, several studies showed a good value of Contrast enhanced endoscopic ultrasound (CEH-EUS) in detecting pancreatic adenocarcinoma, while less is known about other focal pancreatic pathologies. In our retrospective cohort, we can confirm the good value of CEH-EUS for the detection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. We additionally show the high value of instant qualitative evaluation of CEH-EUS images in everyday routine as well as the limitations of quantitative analyses, making precise quantification dispensable. Moreover, we describe perfusion characteristics of several other solid pancreatic masses of different origin.

- Citation: Kannengiesser K, Mahlke R, Petersen F, Peters A, Kucharzik T, Maaser C. Instant evaluation of contrast enhanced endoscopic ultrasound helps to differentiate various solid pancreatic lesions in daily routine. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(1): 19-27

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i1/19.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i1.19

After its first introduction in 1980, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has been established as an effective tool in the diagnostic of intestinal organs. With ongoing technical development image resolution has advanced and ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) opened the chance to cytological assessment of suspicious lesions. In particular identification and evaluation of pancreatic solid and cystic masses as well as their relationship to adjacent vessels and organs have improved through EUS techniques[1].

However, the precise discrimination between benign and malignant pancreatic lesions remains often difficult, amongst other reasons due to non-diagnostic cytological results or misguided fine needle aspirates. Early detection of malignancies is crucial, as surgery is the only potential curative treatment. Unfortunately, both EUS and EUS-FNA lack sufficient accuracy, leading to false positive and false negative results in up to one fifth of cases[2-5].

Surgery should be carried out as soon as possible in malignant lesions due to rapid disease progression. As morbidity and mortality of pancreatic surgery are high, it is crucial to identify benign pancreatic or non-adenocarcinoma lesions[6,7].

Contrast enhanced ultrasound has been shown to be a helpful tool in transabdominal ultrasound. There is increasing experience with benign and malignant masses of the liver, kidney and other solid organs, as well as neoplastic, inflammatory and ischemic lesions e.g., in the intestine[8-12].

Ultrasound contrast agents contain microbubbles filled with gas surrounded by a shell. In harmonic imaging, low acoustic energies with a mechanical index between 0.1 and 0.06 lead to an oscillation of microbubbles in harmonic frequencies, which enhances the scattered ultrasound signal. Moreover, low acoustic energies allow subtraction of the tissue-derived ultrasound signals. As the microbubbles do not leave the microvasculature, this leads to improved detectability of arteries, veines, microvessels and blood perfusion characteristics in different perfusion phases[13].

Sensitivity of transabdominal ultrasound of the pancreas is often limited, mostly due to meteorism. Accuracy of EUS in detection of pancreatic lesions is significantly better[14,15].

New echo-endoscopes allow the use of ultrasound contrast agents in harmonic EUS imaging[16,17].

In some studies, the value of contrast enhanced EUS in the diagnostic of pancreatic masses has been evaluated[18-23], showing good diagnostic value. This was in principally reached with the help of time consuming quantitative ultrasound data analysis later on.

With this study, we want to determine the diagnostic value of qualitative, immediately analysed contrast enhanced harmonic EUS (CEH-EUS) in comparison with precise quantitative analyses for the diagnostic of various pancreatic masses in daily routine in a single centre cohort.

Data of all patients with undetermined solid pancreatic masses who underwent EUS procedures with application of contrast agent was included in the retrospective analysis. Patients with predominantly cystic pancreatic lesions were not included.

Video documented data sets of CEH-EUS investigations of these patients were evaluated. All investigations have been performed during clinical routine procedures.

Investigations were carried out as follows: Standard B-mode EUS was performed in all patients with suspected pancreatic masses. If undetermined masses were found, size, location and echogenicity were documented. The patient underwent CEH-EUS if no contraindications, including, age under 18 years, pregnancy, lactation, severe heart failure, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, known allergic disposition to SonoVue®, were present.

CEH-EUS was performed as follows: Numerous patients with focal pancreatic lesions undergoing EUS investigations in our facility from April 2011 till September 2016 received 5mL SonoVue (Bracco s.p.a., Milan, Italy) via cubital vein catheter, followed by a saline flush. The echoendoscope used was Hitachi/Pentax EG3670URK or EG3870UTK (Hitachi Medical Corp., Tokyo, Japan) the ultrasound processor Hitachi Preirus (Hitachi Medical Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Observation of the pancreatic lesion was performed for at least one minute after SonoVue® injection.

The investigator was not blinded to the previous history of each patient. First clinical evaluation of qualitative contrast agent characteristics (hypoenhanced, isoenhanced, hyperenhanced or non-enhanced) was performed immediately by the investigator upon the endoscopic procedure and documented in the physician’s report. Investigations were carried out by TK, RM, KK and CM, blinded video data analysis later on was performed by KK; all investigators had several years of experience with both EUS and contrast enhanced ultrasound.

Ultrasound video sequences were continuously recorded and then analysed later on, using the analysis software of the ultrasound processor (Hitachi Preirus). This software allows quantification of ultrasound signal intensity over time in regions of interest, which are defined by the analysing physician.

Analysis of the recorded video data included arrival time (AT), time to peak (TTP), maximum intensity gain and area under the curve. To rule out circulation time error, two regions of interest were defined; one in the suspicious pancreatic lesion, one in pancreatic tissue besides the lesion. Hypoenhancement was defined as signal intensity of at least 5 db below, hyperenhancement as signal intensity of at least 5 db above the intensity of the pancreatic tissue surrounding the lesion.

In all patients EUS-FNA, transcutaneous biopsy or surgical resection was performed to allow cytology or histology assessment, which served as the gold standard.

For statistical analyses calculation of means and standard deviations as well as sensitivitiy, specificity, positive and negative predictive values were carried out with the help of SPSS SigmaPlot, V.10.0.0.54. Predictive values were calculated on the basis of the investigated cohort.

As a retrospective analysis, institutional review board approval was seen not to be necessary by the local ethics committee. However, all patients signed informed consent for the investigations and for the contrast agent application.

Data sets of 55 patients were analysed. The mean patient age was 66.5 ± 12.5 years (range: 24-83 years). 32 patients were male and 23 patients were female.

Of those 55 patients, CEH-EUS showed hypoenhanced lesions in 39 cases, while in 13 patients contrast agent characteristics were classified as hyperenhanced by the investigator upon investigation and 3 lesions as non-enhanced. Calculation of signal intensity later on showed signal intensity of 6.1 ± 3.2 db for lesions classified as hypoenhanced and 39.0 ± 13.0 db for lesions classified as hyperenhanced. Non-enhanced lesions showed signal intensity of 1.3 ± 0.3 db (Table 1).

| Hypoenhanced lesions | Hyperenhanced lesions | Σ | |

| Patient age (yr) | 72.1 ± 6.7 | 66.7 ± 15.3 | 66.5 ± 12.5 |

| Gender (m/f) | 23/19 | 9/4 | 32/23 |

| Lesion size (mm) | 34.8 ± 13.7 | 36.0 ± 15.6 | 35.1 ± 14.0 |

| Peak signal intensity (db) | 6.1 ± 3.2 | 39.0 ± 13.0 |

Endosonographic healthy appearing pancreatic tissue showed signal intensity of 23.1 ± 9.1 db.

Concordance of the investigators evaluation and classification of contrast enhancement with precise analysis later on was found to be 100%.

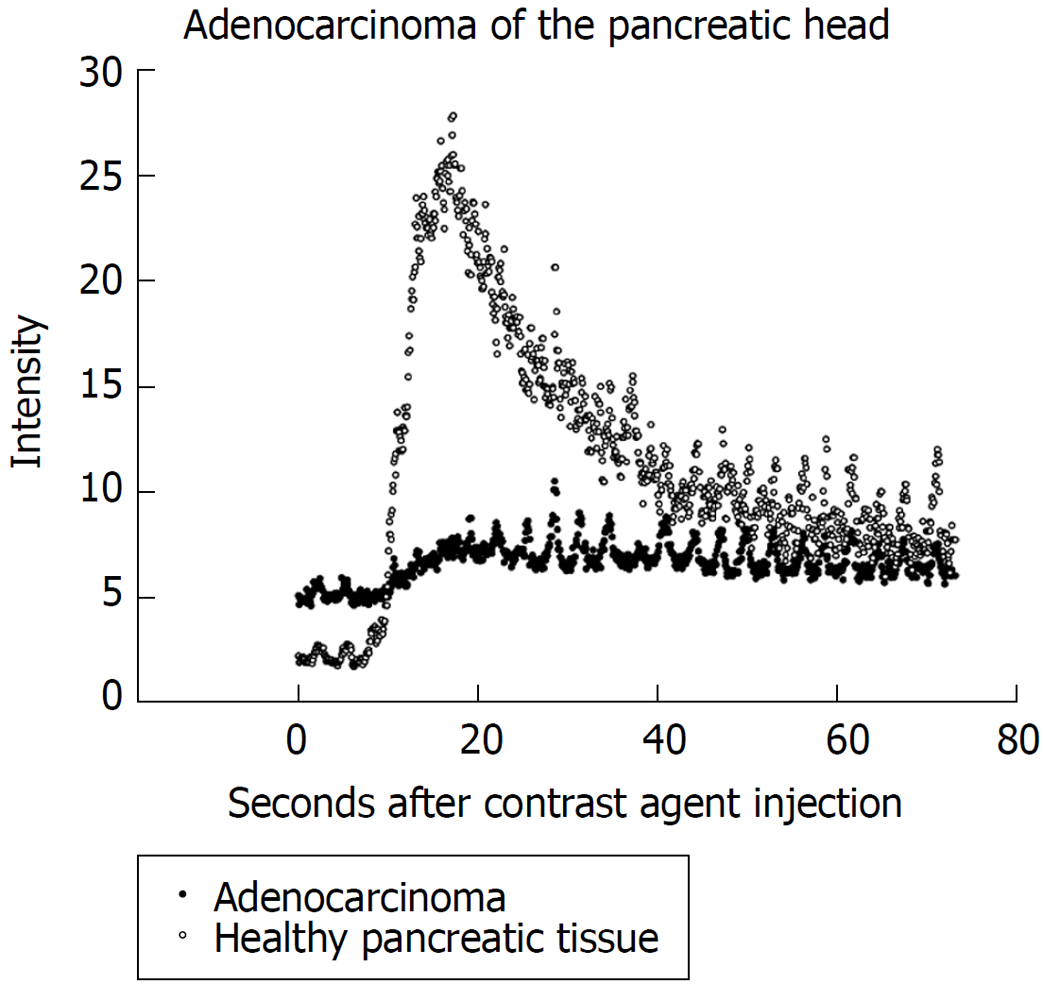

Regarding hypoenhanced lesions, 34 lesions with low contrast enhancement were proven as pancreatic adenocarinoma (intensity 5.7 ± 2.5 db) and in 5 patients chronic pancreatitis lesions showed up hypoenhanced (6.0 ± 3.0 db). Those patients remained under endosonographic follow up including FNA. Figure 1 shows an example of time intensity curves of pancreatic adenocarcinoma compared to healthy pancreatic tissue. All non-enhanced lesions showed up as necrosis of the pancreas.

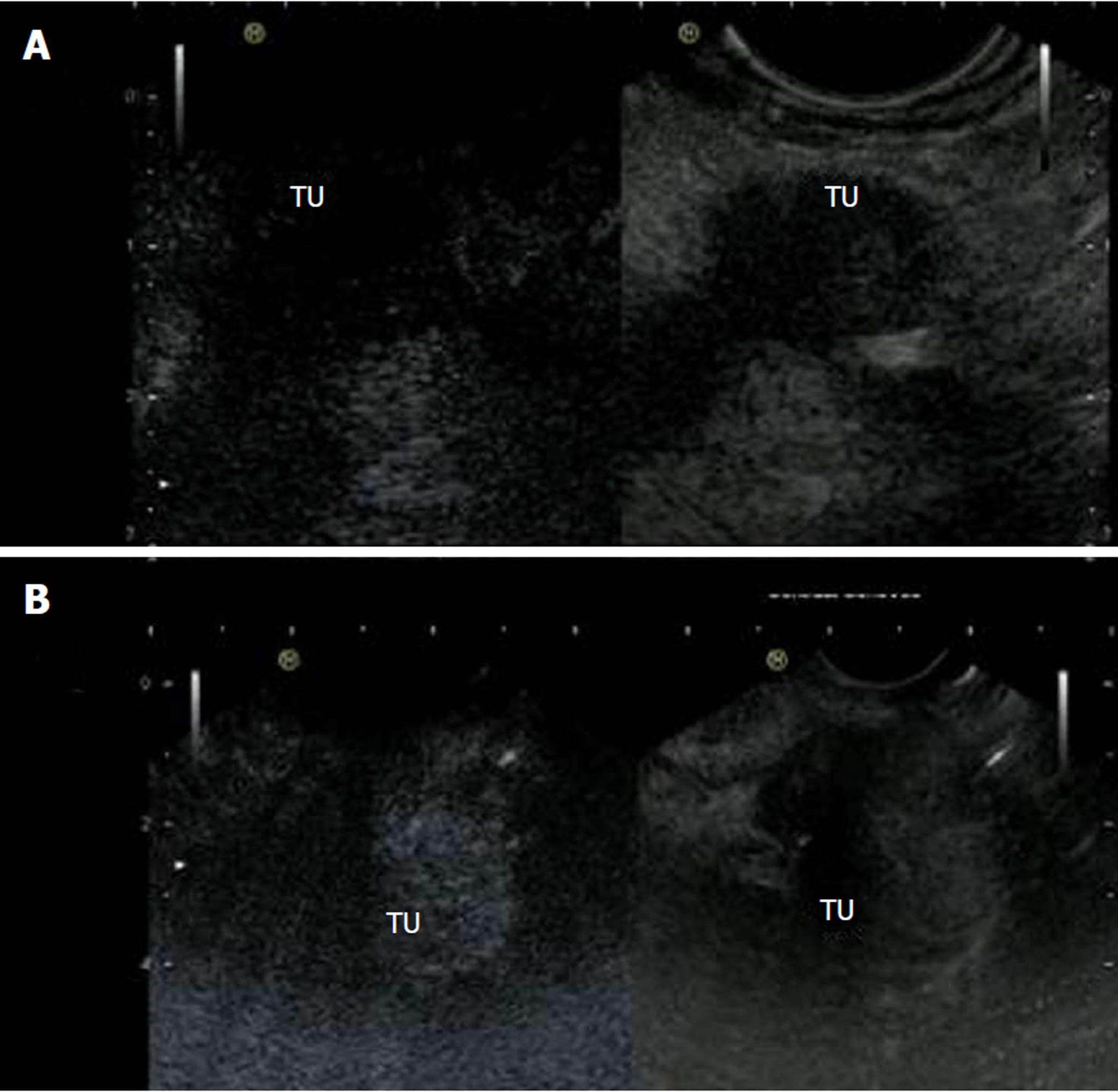

Hyperenhanced lesions were of inflammatory origin in 4 cases (1 patient with autoimmune pancreatitis, 3 patients with active chronic pancreatitis) showing signal intensity of 34.0 ± 11.9 db, in 3 patients due to neuroendocrine carcinoma (33.0 ± 12.0 db), in 1 case a lymphoma (45 db), in 1 case an insulinoma (29 db) and in 4 patients metastases, of which 2 were of renal cell carcinoma and 2 of lung cancer, was diagnosed (56.0 ± 5.6 db). Figure 2 shows ultrasound images of hyperenhanced neuroendocrine carcinoma and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Sensitivity for the detection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma was 100%, specificity 73.6% for low contrast agent enhancement alone. Taking also standard EUS evaluation of the whole pancreas into account, all hypoenhanced lesions in otherwise endosonographically healthy appearing pancreatic tissue were pancreatic adenocarcinoma (sensitivity and specificity 100%). In our cohort, positive predictive value for pancreatic adenocarcinoma was 87.2% for contrast agent characteristics alone, taking native tissue characteristics into account 100%. Negative predictive value was 100% in both cases. Statistics of inflammatory and neoplastic lesions are given in Table 2.

| Peak intensity (db) | Sensitivity | Specifity | PPV | NPV | |

| Hypoenhanced lesions | |||||

| Adenocarcinoma (all in healthy pancreas) | 5.7 ± 2.5 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Chronic pancreatitis lesions | 6.0 ± 3.0 | 100% | 23.30% | 13% | 100% |

| Hyperenhanced lesions | |||||

| Acute inflammatory lesions | 34.0 ± 11.9 | 100% | 79.10% | 30.80% | 81.70% |

| Neoplastic lesions | 32.1 ± 10.2 | 20.90% | 55.50% | 69.20% | 12.80% |

The analysis of further contrast agent characteristics [area under the time intensity curve (AUC), TTP, AT] did not yield helpful results in everyday routine; in 13 hypoenhanced lesions calculation of these parameters was impossible due to low contrast enhancement. In 5 cases data sets of areas used as reference in macroscopic normal appearing tissue could not be analysed for these parameters, mostly due to breathing artefacts. While analysis of AT and TTP did not show clear differences between any lesions and their reference areas, AUC analysis, where possible, showed the same tendency as the maximum peak intensity data, but suffered from substantial interindividual differences and did therefore not improve the diagnostic value (Table 3).

| Lesion | AT lesion (s) | AT non-lesion (s) | TTP lesion (s) | TTP non-lesion (s) | AUC lesion (db × s) | AUC non-lesion (db × s) | PI lesion (db) | PI non-lesion (db) |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | 11.70 ± 3.87 | 11.49 ± 3.26 | 20.58 ± 4.89 | 22.41 ± 6.52 | 238.52 ± 150.63 | 912.34 ± 359.40 | 5.77 ± 2.54 | 21.6 ± 8.6 |

| (n = 25/34) | (n = 31/34) | (n = 25/34) | (n = 31/34) | (n = 25/34) | (n = 31/34) | (n = 34/34) | (n = 34/34) | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 11.92 ± 4.61 | 11 ± 1.00 | 22.42 ± 4.83 | 22.33 ± 1.52 | 424.41 ± 188.83 | 681.96 ± 216.22 | 13.5 ± 12.0 | 22.0 ± 5.8 |

| (n = 4/8) | (n = 6/8) | (n = 4/8) | (n = 6/8) | (n = 4/8) | (n = 6/8) | (n = 8/8) | (n = 8/8) | |

| Neuroendocrine Carcinoma | 10.2 ± 1.98 | 10.0 ± 1.41 | 22.00 ± 1.41 | 20.50 ± 0.70 | 1410.80 ± 535.56 | 855.55 ± 190.14 | 31 ± 8.3 | 20.3 ± 7.5 |

| (n = 3) | (n = 3) | (n = 3) | (n = 3) | (n = 3) | (n = 3) | (n = 3/3) | (n = 3/3) | |

| Metastases (RCC / LC) | 10.00 ± 2.82 | 10.5 ± 2.12 | 30 ± 14.14 | 31.00 ± 15.55 | 2941.95 ± 1067.51 | 1081.40 ± 1096.43 | 56.0 ± 5.6 | 31.5 ± 2.1 |

| (n = 2/2) | (n = 2/2) | (n = 2/2) | (n = 2/2) | (n = 2/2) | (n = 2/2) | (n = 2/2) | (n = 2/2) | |

| Immune-pancreatitis | 12 | 12 | 21 | 22 | 77032 | 6036 | 28 | 16 |

| (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | |

| Lymphoma | 6 | 8 | 11 | 19 | 1570.7 | 913.1 | 45 | 28 |

| (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | |

| Insulinoma | 13 | 13 | 23 | 23 | 721.0 | 802.0 | 16 | 18 |

| (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) | (n = 1) |

With the limitations of a retrospective analysis no side effects of contrast agent application were documented.

In the present study, we assessed the value of the qualitative, immediate analysis of CEH-EUS in the diagnostic of solid pancreatic lesions in comparison to precise and time consuming quantitative processing.

As shown above, CEH-EUS had an excellent diagnostic value if hypoenhanced lesions were detected. Of those lesions located in healthy pancreatic tissue all were diagnosed with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, making cytology results possibly dispensable, especially in the case of resectable lesions preoperatively, thereby reducing the risk for complications e.g., bleeding, infection, or causing local tumor cell seeding. Especially in case of nondiagnostic FNA results, hypoenhanced masses in otherwise healthy pancreatic tissue could be surgically resected without further efforts of cytology sampling.

Accuracy was independent from patient characteristics such as gender, age, comorbidities and tumor size. As harmonic imaging technique, CEH-EUS offers better image resolution than power doppler imaging of suspicious lesions.

While in some other studies quantitative evaluations were helpful[21,24], our data shows the value of this technique in everyday routine by the investigators immediate evaluation of contrast agent characteristics without complex and time consuming image analysis after the actual examination. Moreover, precise quantitative assessment including AUC analysis was of no better value than both measurement of ultrasound signal intensity and qualitative contrast enhancement evaluation during the investigations.

Despite some recent studies[24-26] the value of CEH-EUS to distinguish chronic pancreatitis lesions from malignancies was very limited in our cohort, as on the one hand also benign chronic inflammatory lesions showed up hypoenhanced, on the other hand active inflammation resulted in stronger contrast enhancement. Especially with the increased risk of malignancies in patients with chronic pancreatitis, accurate diagnostic tools are needed, and at least in our hands CEH-EUS alone showed an unsatisfactory sensitivity and specificity. This suggests that in abnormal pancreatic tissue, CEH-EUS still does not offer sufficient accuracy to exclude malignancies, which makes EUS-FNA essential.

The low perfusion of both chronic pancreatitis lesions and pancreatic adenocarcinoma can be explained through the stromal richness of both lesions with only few capillaries. Possibly, EUS elastography of the pancreas may be able to distinguish these lesions from each other[27,28], while data is still limited.

Looking at hyperenhanced lesions, various pathologies including metastases could be detected. This makes histologic or cytologic sampling essential for further treatment and diagnosis.

Diagnostic tools should be easily accessable, quick and easy to apply and safe while showing reliable and reproducible results. Regarding side effects, none were documented in this retrospective analysis, which is consistent with the general experience of SonoVue® application. Although not exactly measured, contrast agent application required only a few extra minutes of investigation and sedation time.

In a prospective analysis, Gincul et al[29] could show that various perfusion parameters which were analysed after CEH-EUS procedures showed good correlation with the diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, which is confirmed by our data. Taking time effectiveness into account, initial evaluation of the contrast agent behaviour was consistent with precise analysis later on. Further calculation of ultrasound data later on does not increase the diagnostic value and therefore does not appear to be necessary, making the contrast enhancement evaluation easy and quick.

EUS itself has become a standard procedure for the diagnostic of intestinal diseases, offering better image resolutions and fewer limitations like meteorism. Although risk of intestinal injury is slightly increased, EUS is in general a well-tolerated and fast spreading technique also with the elderly patients[1,30].

Although it has become a routine procedure, biopsy sampling via EUS-FNA sometimes lacks diagnostic accuracy[3,31], showing false negative and sometimes false positive results while there is the risk of bleeding and infectious complications in addition to a low but potential risk of local seeding of tumor cells[32-35].

Patient safety could therefore be increased and treatment costs could be reduced if patients with potentially resectable hypoenhanced lesions could be preoperatively diagnosed in an outpatient setting without cytologic sampling while those with hyperenhanced lesions definitely require further diagnostics as surgery might not be the optimal choice of treatment.

In conclusion, CEH-EUS showed good diagnostic accuracy, especially in case of hypoenhanced lesions. If situated in healthy pancreatic lesions, pancreatic adenocarcinoma is highly suspicious and patients may be sent for surgical resection without further cytology assessment. In case of hyperenhanced lesions, cytology or histology are crucial for guiding further treatment, as a variety of pathologies may show up with hyperenhancement.

In our hands, CEH-EUS showed excellent results also using qualitative analysis of contrast agent characteristics without complicated and time consuming analyses of ultrasound data later on, proving its value for everyday routine practice.

While some studies have shown that quantitative analysis of contrast enhanced endoscopic ultrasound (CEH-EUS) helps to identify pancreatic adenocarcinoma, there are less data from everyday routine. For non-adenocarcinoma lesions, less information of contrast agent characteristics has been published so far.

As in pancreatic malignancies surgery is the only potential cure, quick and efficient diagnostics are needed to guide further therapy and avoid unnecessary delay. As biopsy sampling from fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) requires diagnostics in an inpatient setting, alternative methods with good diagnostic accuracy would make outpatient diagnostics possible, which would be both time saving and less expensive.

The main research objective was to show the value of CEH-EUS in the daily routine diagnostic of various pancreatic lesions. Besides the hypoenhancement of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, which was quantitatively shown before, various other pancreatic lesions warrent future research.

CEH-EUS data of 55 patients with solid pancreatic lesions were analysed regarding contrast agent characteristics. Statistical analysis of time to peak, peak intensity, area under the time intensity curve, arrival time were compared to qualitative evaluation during the investigation, while histological specimen or FNA results served as gold standard.

All pancreatic adenocarcinoma showed up hypoenhanced, while several other lesions including metases of other origin, lymphoma and inflammatory lesions showed up hyperenhanced. Quantitative analysis oft he EUS data did not add any value to the qualitative evaluation. Moreover, calculation of the quantitative parameters was in some cases difficult, among others due to low signal intensity in hypoenhanced lesions or due to moving artifacts.

Qualitative evaluation of contrast agent characteristics is sufficient to identify pancreatic adenocarcinoma in healthy pancreatic tissue and could make EUS-FNA in patients with resectable disease dispensable. Hyperenhanced pancreatic lesions can be of various origin, which makes histological sampling essential.

Especially for hyperenhanced pancreatic lesions, prospective studies are needed to broaden the experience with this intersting technique. Possibly, algorythms with different techniques such as CEH-EUS and EUS-elastography could further help to classify pancreatic masses in difficult situations such as chronic pancreatitis patients.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Isik A, Kopljar M, Cui XW S- Editor: Dou Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Bian YN

| 1. | Sedlack R, Affi A, Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Norton ID, Clain JE, Wiersema MJ. Utility of EUS in the evaluation of cystic pancreatic lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:543-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kliment M, Urban O, Cegan M, Fojtik P, Falt P, Dvorackova J, Lovecek M, Straka M, Jaluvka F. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of pancreatic masses: the utility and impact on management of patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1372-1379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gleeson FC, Kipp BR, Caudill JL, Clain JE, Clayton AC, Halling KC, Henry MR, Rajan E, Topazian MD, Wang KK, Wiersema MJ, Zhang J, Levy MJ. False positive endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration cytology: incidence and risk factors. Gut. 2010;59:586-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Turner BG, Cizginer S, Agarwal D, Yang J, Pitman MB, Brugge WR. Diagnosis of pancreatic neoplasia with EUS and FNA: a report of accuracy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:91-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Laquière A, Lefort C, Maire F, Aubert A, Gincul R, Prat F, Grandval P, Croizet O, Boulant J, Vanbiervliet G, Pénaranda G, Lecomte L, Napoléon B, Boustière C. 19 G nitinol needle versus 22 G needle for transduodenal endoscopic ultrasound-guided sampling of pancreatic solid masses: a randomized study. Endoscopy. 2018;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Taylor B. Carcinoma of the head of the pancreas versus chronic pancreatitis: diagnostic dilemma with significant consequences. World J Surg. 2003;27:1249-1257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fathy O, Wahab MA, Elghwalby N, Sultan A, EL-Ebidy G, Hak NG, Abu Zeid M, Abd-Allah T, El-Shobary M, Fouad A, Kandeel T, Abo Elenien A, Abd El-Raouf A, Hamdy E, Sultan AM, Hamdy E, Ezzat F. 216 cases of pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors for postoperative complications. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:1093-1098. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Rettenbacher T. Focal liver lesions: role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Eur J Radiol. 2007;64:173-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Xu ZF, Xu HX, Xie XY, Liu GJ, Zheng YL, Liang JY, Lu MD. Renal cell carcinoma: real-time contrast-enhanced ultrasound findings. Abdom Imaging. 2010;35:750-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bertolotto M, Martegani A, Aiani L, Zappetti R, Cernic S, Cova MA. Value of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for detecting renal infarcts proven by contrast enhanced CT. A feasibility study. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:376-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Girlich C, Schacherer D, Lamby P, Scherer MN, Schreyer AG, Jung EM. Innovations in contrast enhanced high resolution ultrasound improve sonographic imaging of the intestine. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2010;45:207-215. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Kannengiesser K, Mahlke R, Petersen F, Peters A, Ross M, Kucharzik T, Maaser C. Contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasound is able to discriminate benign submucosal lesions from gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1515-1520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sanchez MV, Varadarajulu S, Napoleon B. EUS contrast agents: what is available, how do they work, and are they effective? Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:S71-S77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nakaizumi A, Uehara H, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Kitamura T, Kuroda C, Ohigashi H, Ishikawa O, Okuda S. Endoscopic ultrasonography in diagnosis and staging of pancreatic cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:696-700. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Reddymasu SC, Gupta N, Singh S, Oropeza-Vail M, Jafri SF, Olyaee M. Pancreato-biliary malignancy diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasonography in absence of a mass lesion on transabdominal imaging: prevalence and predictors. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1912-1916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kitano M, Sakamoto H, Matsui U, Ito Y, Maekawa K, von Schrenck T, Kudo M. A novel perfusion imaging technique of the pancreas: contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:141-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Imazu H, Uchiyama Y, Matsunaga K, Ikeda K, Kakutani H, Sasaki Y, Sumiyama K, Ang TL, Omar S, Tajiri H. Contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS with novel ultrasonographic contrast (Sonazoid) in the preoperative T-staging for pancreaticobiliary malignancies. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:732-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hocke M, Ignee A, Dietrich CF. Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2011;43:163-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Napoleon B, Alvarez-Sanchez MV, Gincoul R, Pujol B, Lefort C, Lepilliez V, Labadie M, Souquet JC, Queneau PE, Scoazec JY, Chayvialle JA, Ponchon T. Contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasound in solid lesions of the pancreas: results of a pilot study. Endoscopy. 2010;42:564-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kitano M, Kudo M, Yamao K, Takagi T, Sakamoto H, Komaki T, Kamata K, Imai H, Chiba Y, Okada M, Murakami T, Takeyama Y. Characterization of small solid tumors in the pancreas: the value of contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:303-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Matsubara H, Itoh A, Kawashima H, Kasugai T, Ohno E, Ishikawa T, Itoh Y, Nakamura Y, Hiramatsu T, Nakamura M, Miyahara R, Ohmiya N, Ishigami M, Katano Y, Goto H, Hirooka Y. Dynamic quantitative evaluation of contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis of pancreatic diseases. Pancreas. 2011;40:1073-1079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Săftoiu A, Vilmann P, Dietrich CF, Iglesias-Garcia J, Hocke M, Seicean A, Ignee A, Hassan H, Streba CT, Ioncică AM, Gheonea DI, Ciurea T. Quantitative contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS in differential diagnosis of focal pancreatic masses (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:59-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yamashita Y, Kato J, Ueda K, Nakamura Y, Kawaji Y, Abe H, Nuta J, Tamura T, Itonaga M, Yoshida T, Maeda H, Maekita T, Iguchi M, Tamai H, Ichinose M. Contrast-Enhanced Endoscopic Ultrasonography for Pancreatic Tumors. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:491782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gheonea DI, Streba CT, Ciurea T, Săftoiu A. Quantitative low mechanical index contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound for the differential diagnosis of chronic pseudotumoral pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gong TT, Hu DM, Zhu Q. Contrast-enhanced EUS for differential diagnosis of pancreatic mass lesions: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:301-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Park JS, Kim HK, Bang BW, Kim SG, Jeong S, Lee DH. Effectiveness of contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasound for the evaluation of solid pancreatic masses. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:518-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Iglesias-Garcia J, Domínguez-Muñoz JE, Castiñeira-Alvariño M, Luaces-Regueira M, Lariño-Noia J. Quantitative elastography associated with endoscopic ultrasound for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2013;45:781-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Săftoiu A, Vilmann P. Differential diagnosis of focal pancreatic masses by semiquantitative EUS elastography: between strain ratios and strain histograms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:188-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gincul R, Palazzo M, Pujol B, Tubach F, Palazzo L, Lefort C, Fumex F, Lombard A, Ribeiro D, Fabre M, Hervieu V, Labadie M, Ponchon T, Napoléon B. Contrast-harmonic endoscopic ultrasound for the diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a prospective multicenter trial. Endoscopy. 2014;46:373-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kurt M, Oguz D, Oztas E, Kalkan IH, Sayilir A, Beyazit Y, Sasmaz N. Safety of endoscopic ultrasonography in elderly patients: a single center prospective trial. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2013;25:571-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Madhoun MF, Wani SB, Rastogi A, Early D, Gaddam S, Tierney WM, Maple JT. The diagnostic accuracy of 22-gauge and 25-gauge needles in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of solid pancreatic lesions: a meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2013;45:86-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kien-Fong Vu C, Chang F, Doig L, Meenan J. A prospective control study of the safety and cellular yield of EUS-guided FNA or Trucut biopsy in patients taking aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or prophylactic low molecular weight heparin. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:808-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Levy MJ, Gleeson FC, Campion MB, Caudill JL, Clain JE, Halling K, Rajan E, Topazian MD, Wang KK, Wiersema MJ, Clayton A. Prospective cytological assessment of gastrointestinal luminal fluid acquired during EUS: a potential source of false-positive FNA and needle tract seeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1311-1318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Levy MJ, Norton ID, Wiersema MJ, Schwartz DA, Clain JE, Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Wilson WR, Zinsmeister AR, Jondal ML. Prospective risk assessment of bacteremia and other infectious complications in patients undergoing EUS-guided FNA. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:672-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Tomonari A, Katanuma A, Matsumori T, Yamazaki H, Sano I, Minami R, Sen-yo M, Ikarashi S, Kin T, Yane K, Takahashi K, Shinohara T, Maguchi H. Resected tumor seeding in stomach wall due to endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:8458-8461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |