Published online Dec 26, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i16.1217

Peer-review started: October 2, 2018

First decision: October 18, 2018

Revised: November 20, 2018

Accepted: November 23, 2018

Article in press: November 24, 2018

Published online: December 26, 2018

Processing time: 83 Days and 6.1 Hours

Duodenal varices are a lesser-known complication with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. We report a circuitous route from missed diagnosis of duodenal varices to correction. An extremely rare case of duodenal variceal bleeding secondary to idiopathic portal hypertension (IPH) is expounded in this study, which was controlled by transjugular intra-hepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) plus embolization.

A 46-year-old woman with anemia for two years was frequently admitted to the local hospital. Upon examination, anemia was attributed to gastrointestinal tract bleeding, which resulted from duodenal variceal bleeding detected by repeated esophagogastroduodenoscopy. At the end of a complete workup, IPH leading to duodenal varices was diagnosed. Portal venography revealed that the remarked duodenal varices originated from the proximal superior mesenteric vein. TIPS plus embolization with coils and Histoacryl was performed to obliterate the rupture of duodenal varices. The anemia resolved, and the duodenal varices completely vanished by 2 mo after the initial operation.

TIPS plus embolization may be more appropriate to treat the bleeding of large duodenal varices.

Core tip: Duodenal varices are a lesser-known complication of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. The authors report a complicated case of duodenal varices secondary to idiopathic portal hypertension in a patient with recurrent anemia for two years, which were undetected by the endoscopist at a local hospital, but observed by repeated endoscopy in the digestive department in our hospital. The duodenal varices were arrested by transjugular intra-hepatic porto-systemic shunt plus embolization. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report to explore transjugular intra-hepatic porto-systemic shunt treatment for duodenal varices secondary to idiopathic portal hypertension.

- Citation: Xie BS, Zhong JW, Wang AJ, Zhang ZD, Zhu X, Guo GH. Duodenal variceal bleeding secondary to idiopathic portal hypertension treated with transjugular intra-hepatic porto-systemic shunt plus embolization: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(16): 1217-1222

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i16/1217.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i16.1217

Duodenal varices secondary to portal hypertension (PH) are rare, but are most often caused by liver cirrhosis, accounting for 30% of cases. Bleeding duodenal varices are usually massive and fatal, with mortality as high as 40% from the initial bleeding[1]. It also occurs in patients with extra-hepatic portal hypertension, usually owing to portal vein thrombosis and obstruction of the splenic vein and inferior vena cava. Duodenal varices are rarely associated with idiopathic portal hypertension (IPH), which is a lesser-known clinical disorder, consisting of intra-hepatic portal hypertension of unknown etiology characterized by features of splenomegaly, ascites and porto-systemic shunt[2,3]. Patients with IPH initially and commonly present with bleeding gastroesophageal varices.

A 46-year-old woman had symptoms of dizziness and fatigue for two years, during which she suffered from recurrent anemia and frequently required blood transfusions at a local hospital.

Hypoferric anemia was found by bone marrow aspiration, and erosive gastritis was observed by an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in the local hospital. Due to recurrent anemia, she was initially hospitalized in the Department of Hematology in our hospital.

Her father died from liver cirrhosis, and she denied a history of viral hepatitis, alcohol use and schistosomiasis.

During the physical examination, she was pale, yet remained cardiovascularly stable, with the following vital signs on admission: temperature was 37.1°C, heart rate was 92 beats per minute (bpm), initial blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg, and expiration was 20 bpm. In addition, her lungs and heart were found to be normal by auscultation, and the abdomen was soft and flat.

Abnormal laboratory data of complete blood count were as follows: RBC 1.64 × 1012/L, Hb 32 g/L, HCT 0.125%, MCHC 256 g/L, WBC 2.87 × 109/L, PLT 76 × 109/L, and they progressively decreased in the days after admission. Other abnormal results included the following: Positive fecal occult blood test (FOBT), transferrin 2.99 µg/L, HBsAg 138.5 IU/mL, hepatitis B virus DNA 8.01e + 0.03 IU/mL. In addition, bone marrow aspiration revealed hyperplasia of granulocytes, erythrocytes, and platelets.

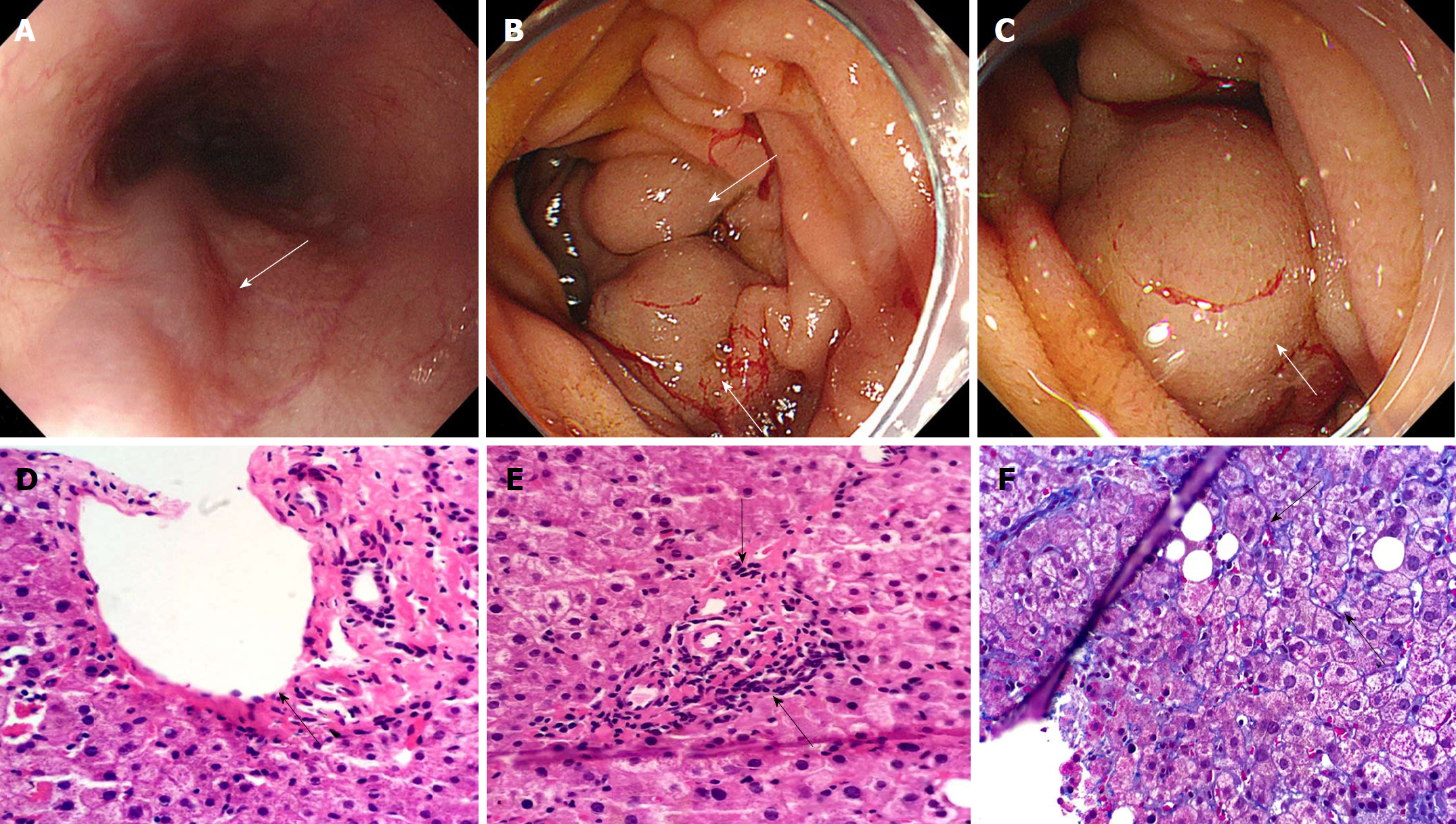

Anemia may be attributed to the bleeding of gastrointestinal tract based on the reduced Hb and RBC count, as well as the positive FOBT. In order to detect the potential cause of hemorrhage, an EGD was performed 5 d after admission to the hospital, and four grade 1 esophageal varices without any evidence of recent bleeding, as illustrated in Figure 1A. Further observation demonstrated the presence of a small amount of fresh blood in the stomach. When reaching the duodenum, the authors observed the occurrence of more fresh blood, as well as evidence of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, and further detected a large submucosal vermicular mass located in the first and second duodenum (Figure 1B and C).

The patient was then transferred to our department to examine the cause of esophageal and duodenal varices associated with portal hypertension, which was followed by the corresponding treatment. In addition to a contrast-enhanced CT scan that demonstrated dilated and tortuous duodenal varix, dilated portal and splenic vein, and splenomegaly, but normal liver, liver function, renal function, coagulation function and liver fibrosis was normal. Serum was negative for anti-hepatitis A, C and E virus antibody, and also negative for autoimmune liver disease and Wilson disease. Moreover, Doppler ultrasound of hepatic vein, portal vein and inferior vein was normal.

Histological evaluation of liver biopsy was performed by two pathologists, aiming to determine the unexplained cause of PH. An integrated structure was observed in hepatic lobule, while there was no evidence of pseudolobuli formation based on Hematoxylin & Eosin staining that was used to detect the extreme extension and occlusion of portal branches in portal regions (Figure 1D and E). Furthermore, periportal and perisinusoidal fibrosis was demonstrated through Masson staining (Figure 1F), suggesting that IPH contributed to these manifestations.

The patient was eventually diagnosed with IPH.

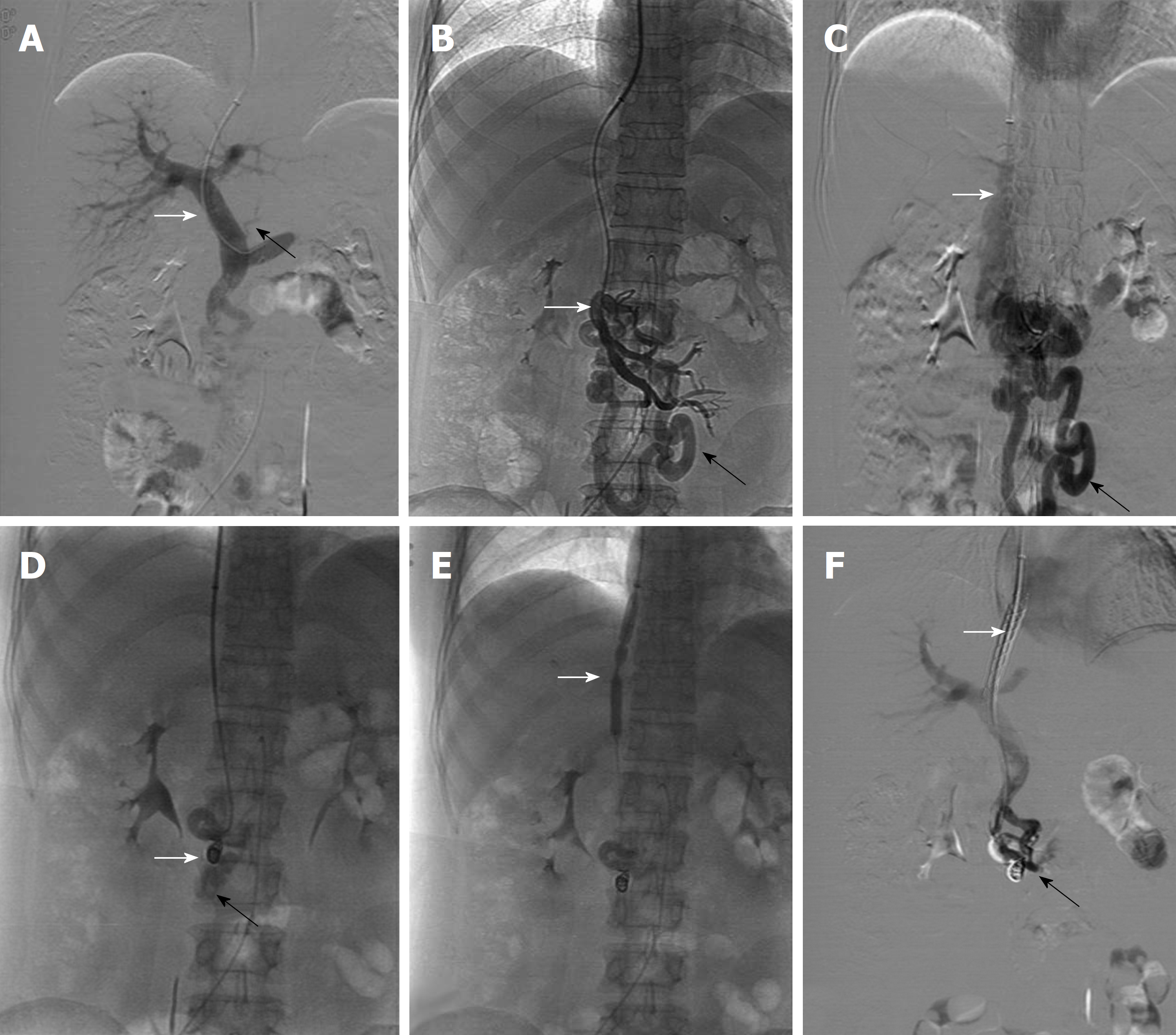

An emergent transjugular intra-hepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) was successfully performed on the day after the patient was transferred. During the TIPS procedure, portal venography initially displayed a mild coronary vein (black arrow in Figure 2A), while the remarkably dilated duodenal varices (Black arrow in Figure 2B and C) were shown to extend from the proximal superior mesenteric vein (White arrow in Figure 2B) with shunting of flow towards the inferior vena cava (White arrow in Figure 2C), in line with EGD observation, which is mainly due to the acute upper GI bleeding, in contrast to the mild esophageal varices. To control GI bleeding, the duodenal varices were initially embolized with three stainless-steel coils, which were 6 mm in diameter (White arrow in Figure 2D), in combination with Histoacryl. Subsequently, a balloon catheter with a diameter of 8 mm and a length of 8 cm was used to dilate the TIPS tract (White arrow in Figure 2E), then a metallic bare stent with a diameter of 8 mm and a length of 8 cm and a fluency covered stent with a diameter of 8 mm and a length of 5 cm (White arrow in Figure 2F) was placed in the tract. Once the TIPS shunt was set up, portal venous pressure significantly decreased from 17.25 mmHg to 10.5 mmHg.

After the TIPS operation, RBC count and Hb markedly increased, and FOBT was negative within 48 h. Anemia was cured 2 mo after TIPS, and there was no sign of varix in the duodenum, as observed by an endoscopy examination.

In this study, the authors reported a rare case of a patient that had been referred to a hematologist because of iron deficiency anemia. Further examination was performed, and the cause of iron deficiency anemia was confirmed to be GI bleeding, primarily resulting from duodenal variceal bleeding. It is difficult to detect duodenal varices, likely due to their concealed and occult location in the duodenum. A gastroenterologist will rarely encounter such conditions because they only account for about 0.4% of all variceal bleeding[4]. Through repeated EGD in our department, a large submucosal vermicular mass was located in the first and second duodenum and further confirmed by TIPS venography.

The patient suffered from PH, characterized by splenomegaly, esophageal and duodenal varix, and enlarged portal and splenic vein. Decompensated liver cirrhosis was excluded by further examination. When PH occurs in the absence of decompensated liver cirrhosis, the most common manifestation is extra-hepatic portal venous block. Nevertheless, no extra-hepatic obstruction was detected by CT and Doppler vascular ultrasound in the portal venous system. Additionally, a number of common causes of portal hypertension, including hepatitis C virus, alcoholic hepatitis, non-alcoholic fatty hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, Wilson’s disease and gallstones, were ruled out. Interestingly, Hepatitis B virus, which is the most common cause of liver cirrhosis in China, was positive. Moreover, the patients had a family history of liver cirrhosis. Thus, a liver biopsy was performed to determine whether the patient suffered from compensated liver cirrhosis associated with PH. Unexpectedly, the pathological feature of cirrhosis was the integrated structure in the hepatic lobule rather than pseudo-nodular, effectively eliminating liver cirrhosis as a possibility. PH with unexplained causes is relatively uncommon. Therefore, liver pathology was performed to assess if IPH contributed to the patient’s PH. As expected, the extreme extension and occlusion of portal branches in portal regions, periportal fibrosis and perisinusoidal fibrosis, as well as the specific pathological characteristics of IPH, were detected in liver sections. It has been generally accepted that the pathological entities of IPH are characterized by hepatoportal sclerosis, periportal and perisinusoidal fibrosis, and nodular regenerative hyperplasia[2]. Furthermore, some rare causes of portal hypertension, such as Biliary diseases (e.g., seronegative PBC, small duct PSC, toxic biliary injury), drug/toxin-induced diseases (e.g., amiodarone, methotrexate, vinyl chloride), granulomatous liver lesions (e.g., schistosomiasis, tuberculosis, mineral oil granuloma, sarcoidosis), Zellweger syndrome, amyloid or light-chain deposition in the space of Disse, Gaucher disease, agnogenic myeloid metaplasia, veno occlusive diseases, granulomatous phlebitis or lipogranulomas are further excluded in the case through histopathological findings. By excluding other causes of PH, IPH was diagnosed at the end of a complete diagnostic workup.

IPH is frequently misdiagnosed as liver cirrhosis, even in well-known hepatology centers. Since IPH was first proposed by an Italian pathologist in 1889, there have been sporadic reports of IPH for decades, most of which were carried out in India[3]. It is not easy to diagnose IPH, due to the fact that there are no typical clinical or lab alterations and that it depends on elucidation of the hepatic pathology[3]. Most IPH patients at an early stage also suffer from esophageal variceal bleeding. However, the occurrence of duodenal varices associated with IPH is extremely rare. In 1988, Tanaka et al[5] reported a case of duodenal variceal bleeding associated with IPH in their study, which was successfully controlled by surgery. In this report, we identified an exceedingly rare case of duodenal variceal bleeding secondary to IPH, which was arrested by TIPS and venous embolism. IPH pathophysiology is poorly understood, but it may be due to an increase in portal flow and/or intrahepatic vascular resistance, due in part to an initial injury to the intrahepatic vascular bed[6]. Recent studies report that over-expression of serum anti-endothelial cell antibodies and deletion of ADAMTS13 may be associated with IPH, which causes splenomegaly and portosystemic communications[2,7-9]. Duodenal varices represent an ectopic portosystemic shunt. Almost half of the patients with duodenal varices also had gastroesophageal varices. Intrahepatic PH was the most common identifiable anatomical source of patients with duodenal varices[5,10].

Intervention radiologic treatment and endoscopic operation have been confirmed to arrest duodenal varix[11]. Besides, endoscopic band ligation and endoscopic injection sclerotherapy have been shown to control acute duodenal variceal bleeding[12,13]. Nonetheless, there are some cases of re-bleeding after endoscopic operation. Consequently, TIPS has been performed to obliterate bleeding of duodenal varices as initial treatment or recurrent bleeding as rescue therapy after failure of endoscopic treatment[14,15]. The authors indicated that a duodenal variceal bleeding associated with IPH was successfully performed by emergent TIPS implantation with dual stent plus embolism with coils and Histoacryl. In contrast to TIPS alone, TIPS plus embolization stopped bleeding in all patients except one[16]. Furthermore, an EGD was performed for a follow-up visit after 2 mo, showing that the dilated varix completely disappeared in the duodenum. Therefore, TIPS plus embolization may be more appropriate to control the rupture or reduce the risk of bleeding of the giant duodenal varices.

In conclusion, we report an extremely rare case of duodenal variceal bleeding secondary to IPH that was controlled by TIPS plus embolization. In future clinical use, it is recommended that TIPS plus embolization with coils and Histoacryl is a good option for treating large ectopic varices.

The duodenum was reported to be normal by the local endoscopist, who missed the diagnosis of duodenal varices, possibly owing to the rare incidence of such disease and the local endoscopist’s inexperience. Misdiagnosis in the local hospital led to the initial admission to the Hematology department, and thus resulted in more complex processes for final diagnosis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Amornyotin S, Lorenzo-Zúñiga V, Sipos F S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Sato T, Akaike J, Toyota J, Karino Y, Ohmura T. Clinicopathological features and treatment of ectopic varices with portal hypertension. Int J Hepatol. 2011;2011:960720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 2. | Khanna R, Sarin SK. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension - diagnosis and management. J Hepatol. 2014;60:421-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Riggio O, Gioia S, Pentassuglio I, Nicoletti V, Valente M, d’Amati G. Idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension: current perspectives. Hepat Med. 2016;8:81-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hashizume M, Tanoue K, Ohta M, Ueno K, Sugimachi K, Kashiwagi M, Sueishi K. Vascular anatomy of duodenal varices: angiographic and histopathological assessments. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1942-1945. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Tanaka T, Kato K, Taniguchi T, Takagi D, Takeyama N, Kitazawa Y. A case of ruptured duodenal varices and review of the literature. Jpn J Surg. 1988;18:595-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hernández-Gea V, Baiges A, Turon F, Garcia-Pagán JC. Idiopathic Portal Hypertension. Hepatology. 2018;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Glatard AS, Hillaire S, d’Assignies G, Cazals-Hatem D, Plessier A, Valla DC, Vilgrain V. Obliterative portal venopathy: findings at CT imaging. Radiology. 2012;263:741-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sato Y, Ren XS, Harada K, Sasaki M, Morikawa H, Shiomi S, Honda M, Kaneko S, Nakanuma Y. Induction of elastin expression in vascular endothelial cells relates to hepatoportal sclerosis in idiopathic portal hypertension: possible link to serum anti-endothelial cell antibodies. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;167:532-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mackie I, Eapen CE, Neil D, Lawrie AS, Chitolie A, Shaw JC, Elias E. Idiopathic noncirrhotic intrahepatic portal hypertension is associated with sustained ADAMTS13 Deficiency. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2456-2465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kochher R, Narasimharao KL, Narasimhan KL, Nagi B, Mitra SK, Mehta S. Duodenal varices. Indian Pediatr. 1988;25:481-483. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Abbar B, Vimpere D, Khater S, Cellier C, Diehl JL. Cerebral infarction following cyanoacrylate endoscopic therapy of duodenal varices in a patient with a patent foramen ovale. Intern Emerg Med. 2018;13:817-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Machida T, Sato K, Kojima A, Takezawa J, Sohara N, Kakizaki S, Takagi H, Mori M. Ruptured duodenal varices after endoscopic ligation of esophageal varices: an autopsy case. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:352-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sato H, Fujishiro H, Rumi MA, Kinoshita Y, Niigaki M, Kohge N, Imaoka T. Successful endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for duodenal varices. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:143-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Saad WE, Lippert A, Schwaner S, Al-Osaimi A, Sabri S, Saad N. Management of Bleeding Duodenal Varices with Combined TIPS Decompression and Trans-TIPS Transvenous Obliteration Utilizing 3% Sodium Tetradecyl Sulfate Foam Sclerosis. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2014;4:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Copelan A, Chehab M, Dixit P, Cappell MS. Safety and efficacy of angiographic occlusion of duodenal varices as an alternative to TIPS: review of 32 cases. Ann Hepatol. 2015;14:369-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vangeli M, Patch D, Terreni N, Tibballs J, Watkinson A, Davies N, Burroughs AK. Bleeding ectopic varices--treatment with transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) and embolisation. J Hepatol. 2004;41:560-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |