Published online Dec 26, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i16.1128

Peer-review started: October 2, 2018

First decision: October 11, 2018

Revised: October 19, 2018

Accepted: November 23, 2018

Article in press: November 24, 2018

Published online: December 26, 2018

Processing time: 82 Days and 15.7 Hours

To evaluate the uptake of a mandatory meningococcal, a highly recommended influenza, and an optional pneumococcal vaccine, and to explore the key factors affecting vaccination rate among health care workers (HCWs) during the Hajj.

An anonymous cross-sectional online survey was distributed among HCWs and trainees who worked or volunteered at the Hajj 2015-2017 through their line managers, or by visiting their hospitals and healthcare centres in Makkah and Mina. Overseas HCWs who accompanied the pilgrims or those who work in foreign Hajj medical missions were excluded. Pearson’s χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables and odds ratio (OR) was calculated by “risk estimate” statistics along with 95% confidence interval (95%CI).

A total of 138 respondents aged 20 to 59 (median 25.6) years with a male to female ratio of 2.5:1 participated in the survey. Only 11.6% (16/138) participants reported receiving all three vaccines, 15.2% (21/138) did not receive any vaccine, 76.1% (105/138) received meningococcal, 68.1% (94/138) influenza and 13.8% (19/138) pneumococcal vaccine. Females were more likely to receive a vaccine than males (OR 3.6, 95%CI: 1.0-12.7, P < 0.05). Willingness to follow health authority’s recommendation was the main reason for receipt of vaccine (78.8%) while believing that they were up-to-date with vaccination (39.8%) was the prime reason for non-receipt.

Some HCWs at Hajj miss out the compulsory and highly recommended vaccines; lack of awareness is a key barrier and authority’s advice is an important motivator. Health education followed by stringent measures may be required to improve their vaccination rate.

Core tip: This survey aimed to assess the uptake of the meningococcal, influenza and pneumococcal vaccines among health care workers (HCWs) within the Hajj workforce, and to explore the facilitators and barriers for their uptake. Key findings of this study are: some HCWs in Hajj, mostly males, failed to receive these vaccines, including the compulsory meningococcal vaccine. Health authority’s recommendation was the main motivator. Lack of awareness about vaccines and the respondents’ perception that they were up-to-date with all vaccinations; were the two main barriers.

- Citation: Badahdah AM, Alfelali M, Alqahtani AS, Alsharif S, Barasheed O, Rashid H, the Hajj Research Team. Mandatory meningococcal vaccine, and other recommended immunisations: Uptake, barriers, and facilitators among health care workers and trainees at Hajj. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(16): 1128-1135

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i16/1128.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i16.1128

Hajj is the largest annual mass gathering event that takes place in designated areas in Makkah, Saudi Arabia where two to three million people assemble from all corners of the world on specific dates of the last month of the lunar calendar. Establishing a healthy environment during Hajj is one of the strategic objectives of the host country[1,2]. Intense congestion during Hajj along with compromised hygiene, shared accommodation and air pollution amplify the risk of meningococcal and other air-borne diseases including influenza and pneumonia[3].

In the last few decades, meningococcal outbreaks from Hajj gathering have been a major global public health concern[4-6]. Two major intercontinental outbreaks of meningococcal disease occurred during Hajj seasons of 1987 (caused by serogroup A) and again during 2000-01 seasons (caused by serogroup W) affected thousands of individuals globally[6-9]. Currently, it is compulsory for anyone, including health care workers (HCWs) who are going to attend congregation, serve pilgrims or reside in Hajj zones whether as pilgrims or seasonal workers to be vaccinated with a quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine (against serogroups A, C, W and Y)[3].

Lately seasonal influenza and pneumonia have been major morbidities among Hajj pilgrims[10-12]. More than 90% of pilgrims develop at least one respiratory symptom while at Hajj[13]. Respiratory viruses, especially influenza, are the most common causes of acute respiratory infections among pilgrims[10,14-16]. The attack rate of influenza among pilgrims ranges from 4% to 15%[17,18]. Currently, influenza vaccination is strongly recommended for Hajj pilgrims and their carers, especially for individuals at higher risk of severe influenza[19].

Pneumonia is a leading cause of hospitalisation, admission to intensive care units, and severe sepsis and septic shock during Hajj[12,20-22]. The point prevalence of pneumonia has risen substantially during Hajj, as it reached up to 340/100000 pilgrims among Iranian in 2005 compared to 4.8/100000 reported in 1986[23-25]. Studies revealed an increase of the pneumococcal nasal carriage up to 2.7-fold before and after Hajj[26,27]. The Saudi Thoracic Society and independent experts also recommend pneumococcal vaccines especially for those at higher risk of complications[28,29].

An estimated 70000 emergency room visits and 12000 hospitalisations occur during a typical Hajj season, and a physician needs to see over 600 patients and a nurse looks after about 400 patients per day during Hajj[30]. To cater for such a large number of pilgrims each year about 30000 HCWs are mobilised from across Saudi Arabia to the Hajj sites in Makkah and Madinah; also, many trainee medics wilfully volunteer at Hajj.

Unvaccinated personnel who have contact with patients put themselves, their colleagues and patients at risk of preventable diseases. Coexistence of Hajj setting as well as excessive workload environment may double these risks. For instance, Al-Asmary et al[31] found that a quarter of HCW in Hajj medical admission developed acute respiratory infections, contact with pilgrims was a significant risk factor for acquisition of this infection. Thus, ensuring vaccination of HCWs at Hajj is very important to protect themselves and their patients. These include mandatory meningococcal vaccine, and highly recommended influenza vaccine; both are funded for HCWs who care for Hajj pilgrims. Yet, the uptake of these vaccines among HCWs at Hajj has been suboptimal[31-35], there is no data on pneumococcal vaccine uptake among HCWs at Hajj. In previous reports non-availability of vaccine and lack of time were key barriers to vaccination among HCWs at Hajj[34,35], however the latest data are not known, and no data on facilitators of vaccination.

To this end, we have conducted a survey to evaluate the uptake of meningococcal, influenza and pneumococcal vaccines among HCWs at Hajj, and explored the key factors that affected vaccine uptake including facilitators of vaccination.

An anonymous cross-sectional online survey was conducted among HCWs and trainees who were employed in Saudi Arabia and worked or volunteered during the Hajj 2015-2017. The survey was distributed among HCWs, including trainees and students who volunteered at Hajj, through their line managers, or by visiting their hospitals and healthcare centres in Makkah and Mina, a major Hajj spot at the outskirt of Makkah. The survey link was sent to the potential participants via short message service, WhatsApp Messenger or email. Overseas HCWs who accompanied the pilgrims or those who work in foreign Hajj medical missions were excluded. Following invitation, the potential respondents acknowledged their acceptance to participate electronically before starting to fill the e-form. The questionnaire included questions about their demographics such as age, gender, current employment, presence or absence of chronic medical conditions, including diabetes, bronchial asthma, other lung or heart diseases, and malignancies. Any participant reporting at least one of these underlying medical conditions and/or aged ≥ 65 years was considered “at increased risk”. The questionnaire then asked if the HCWs received meningococcal, influenza and pneumococcal vaccines as a part of their preparation for secondment at Hajj. It also asked about the reasons for receipt or non- receipt of vaccines. Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) v.25.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Pearson’s χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables and “risk estimate” statistics was used to calculate odds ratio (OR). A two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This study was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board of King Abdullah Medical City, Saudi Arabia (Ref: 15-202). Respondents’ completion of the survey was considered as their implied consent, so signed informed consent was not obtained, and no identifiable personal data were collected.

A total of 138 respondents participated in the survey. Among participants who declared their age (3 did not declare age) the age ranged from 20 to 59 (median 25.6) years with a male to female ratio of 2.5:1. Students/trainee HCWs formed the largest group (41%) followed by nurses (28%) and physicians (16%). Eight per cent (n = 11) respondents were “at increased risk” either because of age or having a pre-existing medical condition. Sixty six per cent (91/138) of the respondents attended Hajj at least once in the past (Table 1).

| No. of participants | Meningococcal vaccine | Influenza vaccine | Pneumococcal vaccine | ||||||||

| Uptake | OR1 (95%CI) | P | Uptake | OR1 (95%CI) | P | Uptake | OR1 (95%CI) | P | |||

| All | |||||||||||

| All Participants | 138 (100) | 105 (76.1) | 94 (68.1) | 19 (13.8) | |||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Male | 98 (71) | 69 (70.4) | 1.0 (ref) | 61 (62.2) | 1.0 (ref) | 14 (14.3) | 1.0 (ref) | ||||

| Female | 40 (29) | 36 (90) | 3.8 (1.2-11.6) | 0.01a | 33 (82.5) | 2.9 (1.1-7.1) | 0.02a | 5 (12.5) | 0.9 (0.3-2.6) | 0.78 | |

| Occupation | |||||||||||

| Students | 57 (41.3) | 41 (71.9) | 1.0 (ref) | 36 (63.2) | 1.0 (ref) | 7 (12.3) | 1.0 (ref) | ||||

| Non-student | 81 (58.7) | 64 (79) | 1.5 (0.7-3.2) | 0.34a | 58 (71.6) | 1.5 (0.7-3.0) | 0.29a | 12 (14.8) | 1.2 (0.5-3.4) | 0.67 | |

| Allied HCW | 15 (10.8) | 11 (73.3) | 8 (53.3) | 0 (0) | |||||||

| Nurse | 39 (28.3) | 31 (79.5) | 28 (71.8) | 7 (17.9) | |||||||

| Pharmacist | 5 (3.6) | 4 (80) | 5 (100) | 1 (20) | |||||||

| Physician | 22 (15.9) | 18 (81.8) | 17 (77.3) | 4 (18.2) | |||||||

| Hajj attendance | |||||||||||

| First time | 47 (34.1) | 34 (72.3) | 1.0 (ref) | 34 (72.3) | 1.0 (ref) | 9 (19.1) | 1.0 (ref) | ||||

| Not first time | 91 (65.9) | 71 (78) | 1.4 (0.6-3.0) | 0.46 | 60 (65.9) | 0.7 (0.3-1.6) | 0.45 | 10 (11) | 0.5 (0.2-1.4) | 0.19 | |

| 2 to 5 times | 65 (47.1) | 49 (75.4) | 39 (60) | 8 (12.8) | |||||||

| > 5 times | 26 (18.8) | 22 (84.6) | 21 (80.8) | 2 (7.7) | |||||||

| Risk group | |||||||||||

| Not at risk | 125 (91.9) | 94 (75.2) | 1.0 (ref) | 83 (66.4) | 1.0 (ref) | 16 (12.8) | 1.0 (ref) | ||||

| At risk | 11 (8.1) | 9 (81.8) | 1.5 (0.3-7.5) | 0.62 | 9 (81.8) | 2.3 (0.5-11) | 0.29 | 3 (27.3) | 2.6 (0.6-10.6) | 0.18 | |

Of all respondents, 11.6% (16/138) reported receiving all three (meningococcal, influenza, pneumococcal) vaccines, 15.2% (21/138) did not receive any of the vaccines, another 2.9% (4/138) were unsure of their vaccination status. Females were more likely to receive a vaccine than males [OR 3.6, 95% confidence interval (95%CI): (1.0-12.7), P < 0.05].

As for meningococcal vaccine, 76.1% (105/138) reported receiving it, 21.7% (30/138) did not receive, and 2.2% (3/138) were unsure (Table 1). Of those who attended Hajj for the first time, 27.7% (13/47) reported not receiving meningococcal vaccine that means 9.4% (13/138) of the whole sample never received this vaccine at all. Sixty two per cent (86/138 received both meningococcal and influenza vaccines. Vaccination against meningococcal disease was significantly higher in females than males (OR 3.8, 95%CI: 1.2-11.6, P = 0.01). Sixty eight per cent (94/138)) reported receiving influenza vaccine, 29% (40/138) did not and 3% (4/138) were unsure. Again, vaccination rate was significantly higher in females than males (OR 2.9, 95%CI: 1.1-7.1, P = 0.02). Only 13.8% (19/138) declared receiving the pneumococcal vaccine as preparation for their Hajj duty, 75.4% (104/138) not received, and 10.9% (15/138) were unsure. No gender difference was observed in the uptake of pneumococcal vaccine.

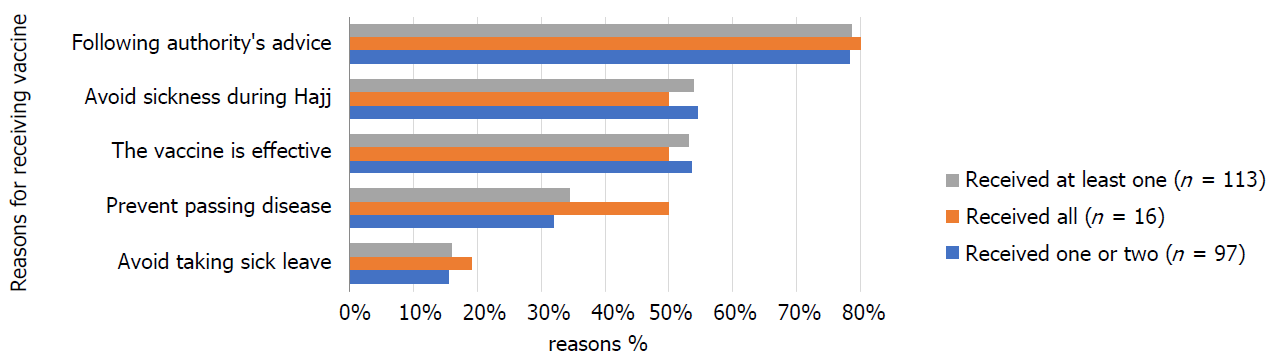

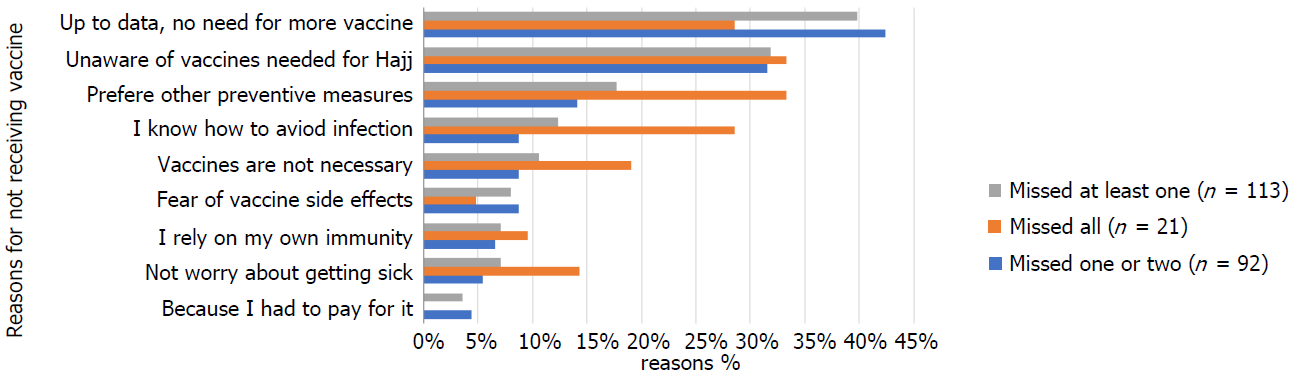

The reasons for receipt and non-receipt of vaccines are listed in Figures 1 and 2 respectively, willingness to follow health authority’s recommendation was the main reason for receipt of vaccine (78.8%) while believing that they were up-to-date with vaccination and hence did not need any more vaccines (39.8%), and unawareness of Hajj vaccines (31.9%) were the prime reasons for non-receipt.

This survey aimed to assess the uptake of the three (meningococcal, influenza, pneumococcal) vaccines among HCWs, a key working group during Hajj, and to explore the important barriers and facilitators. The key findings of this study are that some HCWs at Hajj, mostly males, failed to receive the key Hajj vaccines including the compulsory meningococcal vaccine. Health authority’s recommendation was the main motivator. Lack of awareness about vaccines and a false perception that the respondents were up-to-date with all vaccinations were the two single most important barriers.

Despite the historical importance of meningococcal disease and mandatory requirement of vaccination against it for attending Hajj, at least 9% HCWs and trainees failed to receive the freely available compulsory meningococcal vaccine. In fact, such a poor vaccine uptake was reported in surveys conducted among HCWs in 2003, 2009 and 2014 with the respective uptake of 82.4%, 67.1% and 69.1%[32,33,35]. Non vaccination against a fatal disease among HCWs, who often provide intensive medical care to ill pilgrims, is a grave concern.

Meningococcal vaccination is a visa requirement for international pilgrims, so the vaccine coverage is essentially 100%[36,37], however domestic pilgrims and HCWs evade such requirement leading to suboptimal vaccination rate as low as 64% among domestic pilgrims compared to 100% vaccination rate among UK pilgrims[37]. However, achieving optimum vaccination by the appropriate vaccine is still challenge even among the overseas pilgrims. For instance, a minority of Nigerian pilgrims were found to be vaccinated with the monovalent meningococcal serogroup A vaccine whereas the policy was to use the quadrivalent ACWY vaccine[38]. Occasional use of fake vaccination certificate was another challenge in some countries[39].

Influenza vaccination of HCWs during Hajj is highly recommended[19], yet 29% participants in this study reported not receiving it before attending Hajj. Four previous studies evaluated the coverage of influenza vaccination among HCWs in Hajj with the uptake ranged from as low as 5.9% in 2003, to 61.6% in 2005, 50.9% in 2009 and 52.7% in 2013-15[31-33,40]. Even the uptake of the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic vaccine remained between 22% and 47%[33,34].

The uptake rate in non-Hajj setting is almost similar, ranging from 21% to 51% in several surveys conducted between 2003 and 2014[41-45], and among Saudi medical students it reached 57.2% in 2017[46]. Furthermore, a strong vaccine hesitancy was revealed in a recent study where 13% of HCWs reported not taking influenza vaccine in the past, and would not receive it in the future[47].

Although recent increase in influenza vaccination rate is promising, the suboptimal uptake in this important occupational group, who are expected to be vaccinated even when not serving at Hajj, is a concern. Recently, Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health (MoH) have made the Basic Infection Control Skills License (BICSL), mandatory for all HCWs. BICSL licensure includes, among others, receiving meningococcal and influenza vaccines and the measure is expected to enhance the coverage of both vaccines among HCWs.

The lower uptake rate of meningococcal and influenza vaccines among males could be due to their lower preventative sense, notably towards preemptive and pre-travel advices, or could be a chance finding seeing that most of the survey participants were male[48]. A Dutch study involving Hajj pilgrims showed that being a female was an independent predictor for accepting dTP vaccine[49].

Although no official recommendation for routine pneumococcal vaccination for HCWs exists, experts have recommended it for Hajj attendees considered to be “at increased risk”[28,29]. Our findings showed suboptimal vaccination rate (13.8%) even among “at increased risk” group (27.3%). Previously, a much lower vaccination rate (1.5%) was reported among “at increased risk” international pilgrims, however, much higher uptake (29%-48%) among “at increased risk” pilgrims from developed countries is reported[50].

Promisingly, the main reason for receipt of vaccines was to follow the health authority’s recommendation but there were several key misperceptions. A false belief among HCWs that they were up-to-date with their vaccinations and that they did not need any more vaccines for Hajj attendance was a key barrier. This belief may have stemmed from their lack of awareness about the requirement and the availability of Hajj vaccines, and their presumption that just for joining the congregation they may not need the vaccinations since they were local residents. HCWs’ reliance on other preventive measures and their claimed ability to know how to ward off an infection without vaccination were other important barriers. Some of these barriers were previously reported among HCWs serving at Hajj[34,35]. Workplace vaccination campaigns could make a difference and was found to be successful in Saudi Arabia. For instance, assigning a dedicated nurse in each department to conduct vaccinations during an annual in-hospital campaign increased staff influenza vaccination up to three folds at a tertiary hospital in Saudi Arabia (from 29% to 77%, 81% and 67%)[45].

The strength of this survey is that it gives a very quick snapshot about Hajj HCWs’ uptake of three vaccines: a mandatory vaccine (meningococcal), a highly desirable vaccine (influenza), and an optional vaccine (pneumococcal), and for the first time provides insight on motivators of vaccination. However, this study is fraught with limitations. Small sample size is a key limitation of this survey, HCWs are too busy to complete a survey form, hence like most other surveys involving HCWs at Hajj it has a small sample size. Also, the data are self-reported, and we had no way to validate their vaccination histories but since HCWs are expected to have sufficient health literacy the information are considered to be reliable. The survey did not distinguish between polysaccharide and conjugate meningococcal vaccines, and both vaccines were used in Saudi Arabia during the survey period. Furthermore, the questionnaire did not distinguish those who received the meningococcal vaccine in the previous years versus the current year. Finally, since the survey was online and because we wanted to make it simple for the busy HCWs, we did not ask about reasons for receipt or non-receipt of individual vaccines, so the responses received could be meant for any one or all the three vaccines.

In conclusion, this survey shows that many HCWs at Hajj miss out the compulsory and highly recommended vaccines; lack of awareness is a key barrier and authority’s advice is an important motivator. Health education followed by stringent measures may be required to improve their vaccination rate. Evaluation of the role of on-going measures such as workplace vaccination campaigns and the BICSL is needed to better understand the uptake of vaccination among HCWs at Hajj.

In the last few decades, meningococcal outbreaks from Hajj gathering have been a major global public health concern. It is now compulsory for anyone who is going to attend Hajj congregation or serve the pilgrims to be vaccinated with a quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine (against serogroups A, C, W and Y). Seasonal influenza vaccine is also highly advised for all Hajj attendees, and pneumococcal vaccine is recommended for pilgrims with co-morbidities.

The uptake of these vaccines among health care workers (HCWs) at Hajj has been suboptimal and there is no data on pneumococcal vaccine uptake. In previous reports non-availability of vaccine and lack of time were key barriers to vaccination among HCWs at Hajj, however there is no data on facilitators of vaccination.

The objectives are to evaluate the uptake of meningococcal, influenza, pneumococcal vaccines among HCWs who serve at Hajj, and to explore the key factors, including facilitators, affecting their vaccination rate.

An anonymous cross-sectional online survey was conducted among HCWs and trainees who worked or volunteered at the Hajj 2015-2017 in Makkah and Mina. Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to compare categorical variables; and odds ratio (OR) was calculated by “risk estimate” statistics along with 95% confidence interval (95%CI).

A total of 138 respondents aged 20 to 59 (median 25.6) years with a male to female ratio of 2.5 participated in the survey. Only 11.6% (16/138) participants reported receiving all three vaccines, 15.2% (21/138) did not receive any vaccine; 76.1% (105/138) received meningococcal, 68.1% (94/138) influenza and 13.8% (19/138) pneumococcal vaccine. Females were more likely to receive a vaccine than males (OR 3.6, 95%CI: 1.0-12.7, P < 0.05). Willingness to follow health authority’s recommendation was the main reason for receipt of vaccine (78.8%) while believing that they were up-to-date with vaccination (39.8%) was the prime reason for non-receipt.

This survey shows that many HCWs at Hajj miss out the compulsory and highly recommended vaccines; lack of awareness is a key barrier and authority’s advice is an important motivator.

Achieving satisfactory vaccination coverage among local HCWs at Hajj remains a challenge. Health education followed by stringent measures may be required to improve their vaccination rate. Evaluation of the role of workplace vaccination campaigns and the “Basic Infection Control Skills License” should be considered to better understand the uptake of vaccination among HCWs at Hajj.

The authors wish to thank the respondents and their line managers for their participation/cooperation in the survey.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chowdhury FH, Rosales C S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Memish ZA. Saudi Arabia has several strategies to care for pilgrims on the Hajj. BMJ. 2011;343:d7731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Mass gathering medicine: 2014 Hajj and Umra preparation as a leading example. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;27:26-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Al-Tawfiq JA, Gautret P, Memish ZA. Expected immunizations and health protection for Hajj and Umrah 2018 -An overview. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2017;19:2-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Badahdah AM, Rashid H, Khatami A, Booy R. Meningococcal disease burden and transmission in crowded settings and mass gatherings other than Hajj/Umrah: A systematic review. Vaccine. 2018;36:4593-4602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wilder-Smith A. Meningococcal vaccine in travelers. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:454-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yezli S, Assiri AM, Alhakeem RF, Turkistani AM, Alotaibi B. Meningococcal disease during the Hajj and Umrah mass gatherings. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;47:60-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Novelli VM, Lewis RG, Dawood ST. Epidemic group A meningococcal disease in Haj pilgrims. Lancet. 1987;2:863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Moore PS, Reeves MW, Schwartz B, Gellin BG, Broome CV. Intercontinental spread of an epidemic group A Neisseria meningitidis strain. Lancet. 1989;2:260-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hajjeh R, Lingappa J. Meningococcal disease in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: an evaluation of disease surveillance and control after an outbreak of serogroup W-135 meningococcal disease. CDC Rep. 2000;23:2000. |

| 10. | Memish ZA. The Hajj: communicable and non-communicable health hazards and current guidance for pilgrims. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19671. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Al-Ghamdi SM, Akbar HO, Qari YA, Fathaldin OA, Al-Rashed RS. Pattern of admission to hospitals during muslim pilgrimage (Hajj). Saudi Med J. 2003;24:1073-1076. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Madani TA, Ghabrah TM, Al-Hedaithy MA, Alhazmi MA, Alazraqi TA, Albarrak AM, Ishaq AH. Causes of hospitalization of pilgrims in the Hajj season of the Islamic year 1423 (2003). Ann Saudi Med. 2006;26:346-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Deris ZZ, Hasan H, Sulaiman SA, Wahab MS, Naing NN, Othman NH. The prevalence of acute respiratory symptoms and role of protective measures among Malaysian hajj pilgrims. J Travel Med. 2010;17:82-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rashid H, Shafi S, Booy R, El Bashir H, Ali K, Zambon M, Memish Z, Ellis J, Coen P, Haworth E. Influenza and respiratory syncytial virus infections in British Hajj pilgrims. Emerg Health Threats J. 2008;1:e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moattari A, Emami A, Moghadami M, Honarvar B. Influenza viral infections among the Iranian Hajj pilgrims returning to Shiraz, Fars province, Iran. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2012;6:e77-e79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Memish ZA, Assiri AM, Hussain R, Alomar I, Stephens G. Detection of respiratory viruses among pilgrims in Saudi Arabia during the time of a declared influenza A(H1N1) pandemic. J Travel Med. 2012;19:15-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gautret P, Benkouiten S, Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Hajj-associated viral respiratory infections: A systematic review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14:92-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Alfelali M, Rashid H. Prevalence of influenza at Hajj: is it correlated with vaccine uptake? Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2014;14:213-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zeitouni MO, Al Barrak AM, Al-Moamary MS, Alharbi NS, Idrees MM, Al Shimemeri AA, Al-Hajjaj MS. The Saudi Thoracic Society guidelines for influenza vaccinations. Ann Thorac Med. 2015;10:223-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Baharoon S, Al-Jahdali H, Al Hashmi J, Memish ZA, Ahmed QA. Severe sepsis and septic shock at the Hajj: etiologies and outcomes. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2009;7:247-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Madani TA, Ghabrah TM, Albarrak AM, Alhazmi MA, Alazraqi TA, Althaqafi AO, Ishaq A. Causes of admission to intensive care units in the Hajj period of the Islamic year 1424 (2004). Ann Saudi Med. 2007;27:101-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Alqahtani AS, Tashani M, Ridda I, Gamil A, Booy R, Rashid H. Burden of clinical infections due to S. pneumoniae during Hajj: A systematic review. Vaccine. 2018;36:4440-4446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Prevention of pneumococcal infections during mass gathering. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:326-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Meysamie A, Ardakani HZ, Razavi SM, Doroodi T. Comparison of mortality and morbidity rates among Iranian pilgrims in Hajj 2004 and 2005. Saudi Med J. 2006;27:1049-1053. [PubMed] |

| 25. |

Ghaznawi HI, Khalil MH.

Health hazards and risk factors in the 1406 H (1986 G) Hajj season. |

| 26. | Memish ZA, Assiri A, Almasri M, Alhakeem RF, Turkestani A, Al Rabeeah AA, Akkad N, Yezli S, Klugman KP, O’Brien KL. Impact of the Hajj on pneumococcal transmission. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:77.e11-77.e18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Benkouiten S, Gautret P, Belhouchat K, Drali T, Salez N, Memish ZA, Al Masri M, Fournier PE, Brouqui P. Acquisition of Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage in pilgrims during the 2012 Hajj. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:e106-e109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rashid H, Abdul Muttalif AR, Mohamed Dahlan ZB, Djauzi S, Iqbal Z, Karim HM, Naeem SM, Tantawichien T, Zotomayor R, Patil S. The potential for pneumococcal vaccination in Hajj pilgrims: expert opinion. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2013;11:288-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Alharbi NS, Al-Barrak AM, Al-Moamary MS, Zeitouni MO, Idrees MM, Al-Ghobain MO, Al-Shimemeri AA, Al-Hajjaj MS. The Saudi Thoracic Society pneumococcal vaccination guidelines-2016. Ann Thorac Med. 2016;11:93-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Almalki M, Fitzgerald G, Clark M. Health care system in Saudi Arabia: an overview. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17:784-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Al-Asmary S, Al-Shehri AS, Abou-Zeid A, Abdel-Fattah M, Hifnawy T, El-Said T. Acute respiratory tract infections among Hajj medical mission personnel, Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2007;11:268-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Madani TA, Ghabrah TM. Meningococcal, influenza virus, and hepatitis B virus vaccination coverage level among health care workers in Hajj. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Memish ZA, Assiri AM, Alshehri M, Hussain R, Alomar I. The prevalance of respiratory viruses among healthcare workers serving pilgrims in Makkah during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2012;10:18-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ahmed GY, Balkhy HH, Bafaqeer S, Al-Jasir B, Althaqafi A. Acceptance and Adverse Effects of H1N1 Vaccinations Among a Cohort of National Guard Health Care Workers during the 2009 Hajj Season. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | AlQuliti KW, Tajaddin WA, Habeeb HA, As-Saedi ES, Sheerah SA, Al-Ayoubi RM, Bukhary ZA. Meningococcal immunization among emergency room health care workers in Almadinah Almunawwarah, Saudi Arabia. JTUSCI. 2015;10:175-180. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Memish ZA, Yezli S, Almasri M, Assiri A, Turkestani A, Findlow H, Bai X, Borrow R. Meningococcal serogroup A, C, W, and Y serum bactericidal antibody profiles in Hajj pilgrims. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;28:171-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | El Bashir H, Rashid H, Memish ZA, Shafi S; Health at Hajj and Umra Research Group. Meningococcal vaccine coverage in Hajj pilgrims. Lancet. 2007;369:1343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Memish ZA, Assiri A, Almasri M, Alhakeem RF, Turkestani A, Al Rabeeah AA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Alzahrani A, Azhar E, Makhdoom HQ. Prevalence of MERS-CoV nasal carriage and compliance with the Saudi health recommendations among pilgrims attending the 2013 Hajj. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:1067-1072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Bateman C. Haj threat creates huge fraud potential. S Afr Med J. 2002;92:178-179. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Alfelali M, Barasheed O, Badahdah AM, Bokhary H, Azeem MI, Habeebullah T, Bakarman M, Asghar A, Booy R, Rashid H; Hajj Research Team. Influenza vaccination among Saudi Hajj pilgrims: Revealing the uptake and vaccination barriers. Vaccine. 2018;36:2112-2118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Alshammari TM, AlFehaid LS, AlFraih JK, Aljadhey HS. Health care professionals’ awareness of, knowledge about and attitude to influenza vaccination. Vaccine. 2014;32:5957-5961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Al-Tawfiq JA, Antony A, Abed MS. Attitudes towards influenza vaccination of multi-nationality health-care workers in Saudi Arabia. Vaccine. 2009;27:5538-5541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Rehmani R, Memon JI. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in a Saudi hospital. Vaccine. 2010;28:4283-4287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Al-Tawfiq JA. Willingness of health care workers of various nationalities to accept H1N1 (2009) pandemic influenza A vaccination. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32:64-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Al-Otaibi BM, El-Saed A, Balkhy HH. Influenza vaccination among healthcare workers at a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia: Facing challenges. Ann Thorac Med. 2010;5:120-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Abalkhail MS, Alzahrany MS, Alghamdi KA, Alsoliman MA, Alzahrani MA, Almosned BS, Gosadi IM, Tharkar S. Uptake of influenza vaccination, awareness and its associated barriers among medical students of a University Hospital in Central Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10:644-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Alabbad AA, Alsaad AK, Al Shaalan MA, Alola S, Albanyan EA. Prevalence of influenza vaccine hesitancy at a tertiary care hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11:491-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Schlagenhauf P, Chen LH, Wilson ME, Freedman DO, Tcheng D, Schwartz E, Pandey P, Weber R, Nadal D, Berger C. Sex and gender differences in travel-associated disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:826-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Keles H, Sonder GJ, van den Hoek A. Predictors for the uptake of recommended vaccinations in Mecca travelers who visited the Public Health Service Amsterdam for mandatory meningitis vaccination. J Travel Med. 2011;18:198-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Alqahtani AS, Rashid H, Heywood AE. Vaccinations against respiratory tract infections at Hajj. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:115-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |