Published online Nov 6, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i13.688

Peer-review started: July 11, 2018

First decision: August 3, 2018

Revised: August 7, 2018

Accepted: October 9, 2018

Article in press: October 9, 2018

Published online: November 6, 2018

Processing time: 118 Days and 7 Hours

A 48 year-old Chinese woman suffering from polyarthritis, irregular fever and trichomadesis was admitted to the hospital. A diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) was made based on polyarthritis, pancytopenia, reduced complement 3, multiple positive autoantibodies, a positive Coomb’s test and protein in her urine. In addition, splenomegaly was detected during physical examination and confirmed by abdominal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging, indicating that the patient had SLE and portal hypertension. Further negative investigations ruled out the possibility of cirrhosis. The patient was diagnosed with active SLE complicated by noncirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) without liver histopathology, due to the patient’s refusal for liver biopsy. Portal vein diameter and splenomegaly decreased following treatment with methylprednisolone, hydroxychloroquine and metoprolol tartrate. To date, SLE complicated by NCPH has rarely been reported, as it is under-recognized clinically as well as pathologically. Here we describe a case of SLE complicated by NCPH and review the literature for its characteristics, which may contribute to improving the recognition of NCPH and reducing missed and delayed diagnosis of this disorder.

Core tip: It is rare when systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) complicated by noncirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) is reported, likely because it is under-recognized clinically as well as pathologically. NCPH should be considered in any patient with SLE who suffers from clinical manifestations of portal hypertension in the absence of cirrhosis evidence. Magnetic resonance imaging could be one of several non-invasive detection methods used to rule out cirrhosis. The recognition of clinical presentation and associated risk factors of NCPH contributes to the reduction of its missed and delayed clinical diagnoses.

- Citation: Yang QB, He YL, Peng CM, Qing YF, He Q, Zhou JG. Systemic lupus erythematosus complicated by noncirrhotic portal hypertension: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(13): 688-693

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i13/688.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i13.688

Portal hypertension is a common clinical disease, and the most common cause is cirrhosis[1]. When patients present with signs and symptoms of portal hypertension without evidence of cirrhosis, the condition is known as noncirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH). NCPH has been reported in a number of immunologic diseases[1], such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic sclerosis. Although liver disease is present in approximately one third of SLE patients, it is usually asymptomatic or mild[2]. The majority of these hepatic diseases are due to drug-induced injury, autoimmune hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis[3]. NCPH is considered rare[3]. Therefore, although the diagnosis of NCPH requires clinical exclusion of other conditions that can cause portal hypertension, it is under-recognized clinically as well as pathologically. To date, only 22 cases of NCPH associated with SLE have been reported according to our literature search[4-16] (Table 1). In this report, we describe a case of a Chinese patient with SLE complicated by NCPH, and review the characteristics of NCPH in the literature to improve recognition and to reduce missed and delayed diagnosis of this disorder.

| No. | Author | Yr | Age/sex | Interval between SLE and NCPH (yr) | Complicated by other diseases | Positive immunological markers | Hepatic dysfunction | Portal thrombosis | Hepatic histopathology | Treatment of SLE |

| 1 | Woolf et al[4] | 1994 | 19/F | 8 | PAH | ANA, dsDNA, CIC, CH50 | No | No | PF | GCs, CTX |

| 2 | Takahaski et al[5] | 1995 | 26/M | 5.5 | ACL, AMI | ANA, dsDNA, ACL, CH50, IgG | Yes | No | PF | GCs |

| 3 | Sekiya et al[6] | 1997 | 43/F | N/A | No | ANA, dsDNA, CH50, IgG | Yes | No | NRH | GCs |

| 4 | Nakajima et al[7] | 1999 | 29/M | 3 | No | ANA, CH50 | Yes | No | PF | GCs, AZA |

| 5 | Inagaki et al[8] | 2000 | 38/M | 12 | No | LA, ACL, CH50 | Yes | No | PF | GCs |

| 6 | Horita et al[9] | 2002 | 40/F | 14 | No | ANA, dsDNA | No | No | NRH | GCs |

| 7 | Colmegna et al[10] | 2005 | 39/F | 8 | PAH | ANA, dsDNA, ACL | No | No | NRH | GCs, CTX |

| 8 | Park et al[11] | 2006 | 37/F | 3 | PAH | ANA, dsDNA, RNP, Smith | Yes | No | NRH | GCs, HCQ |

| 9 | Leung et al[12] | 2007 | 37/F | 0 | ITP | ANA, dsDNA, ACL | Yes | No | NRH | GCs |

| 10 | Leung et al[13] | 2009 | 54/F | 14 | No | N/A | Yes | No | NRH | GCs, AZA |

| 11 | Leung et al[13] | 2009 | 56/F | 18 | No | N/A | No | No | NRH | GCs |

| 12 | Leung et al[13] | 2009 | 56/F | 5 | No | N/A | Yes | No | NRH | GCs, AZA |

| 13 | Louwers et al[14] | 2012 | 37/F | N/A | No | N/A | Yes | No | NRH | GCs, AZA |

| 14 | Guo et al[15] | 2012 | N/A | N/A | No | ANA, dsDNA, SSA, IgG | Yes | No | NRH | MTX |

| 15 | Guo et al[15] | 2012 | N/A | N/A | No | ANA ,ACL, SMA | No | No | NRH | AZA |

| 16 | Guo et al[15] | 2012 | N/A | N/A | Cryoglobulinemia | ANA, dsDNA, RNP, IgG | No | No | NRH | CTX |

| 17 | Guo et al[15] | 2012 | N/A | N/A | PIF | Smith, RNP, IgG | Yes | No | NRH | CTX |

| 18 | Guo et al[15] | 2012 | N/A | N/A | PAH, PTE | ANA, Smith | No | No | NRH | CTX |

| 19 | Zhang et al[16] | 2017 | 35/F | 2 | PCP | ANA, ANUA | No | No | NRH, PF | GCs, CsA |

| 20 | Zhang et al[16] | 2017 | 41/F | 6 | PCP | ANA, dsDNA, ANUA | No | No | NRH | GCs, MTX |

| 21 | Zhang et al[16] | 2017 | 25/F | 9.5 | PCP | ANA, ACL, ANUA | No | No | N/A | GCs, MTX |

| 22 | Zhang et al[16] | 2017 | 25/F | 10 | PCP | ANA, dsDNA, ACL, ANUA | Yes | No | N/A | GCs, MTX |

A 48 year-old Chinese woman was first admitted to the hospital two years ago with hematuria, dysuria, urinary frequency and urgency. Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-Smith antibody, anti-SSA/Ro60 and anti-Ro52 tests were positive. Due to strongly positive anti-SSA/Ro60 and anti-Ro52, salivary gland function was examined in order to eliminate Sjǒgren’s syndrome, although she did not have dry eyes or dry mouth. She was diagnosed with undifferentiated connective tissue disease and urinary infection, and was treated with hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and total glucosides of paeony (TGP) maintained for two years after hospital discharge. However, she had repeated episodes of polyarthritis, irregular fever (maximum body temperature of 41 °C) and trichomadesis.

She was admitted again to the hospital due to polyarthritis and fever on August 22, 2017. There was no history of hepatitis, tuberculosis, or diabetes and no previous neurological disturbance. In addition to polyarthritis and fever, splenomegaly was incidentally observed during physical examination upon admission. At this time, her full blood count showed mild pancytopenia (PCP): hemoglobin was 100 g/L, platelet count 85 × 109/L and white blood cell count 3.99 × 109/L. Serum biochemistry tests including hepatic and renal functions were normal, apart from mildly elevated C-reactive protein (12.22 g/L, reference 0.00-9.00 g/L) and reduced albumin (26 g/L, reference 40.0-55.0 g/L). Multiple autoantibodies were positive, including ANA, anti-nucleosome antibody, anti-double stranded DNA, anti-SSA/Ro60, anti-SSB/La and anti-Ro52. Complement 3 was reduced. Coomb’s test and urinary protein were also mildly positive, and urinary total protein was 459.8 mg per 24 h urine. Other investigations for differential diagnosis showed that both rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody were negative, and her prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, procalcitonin and blood culture tests were all normal.

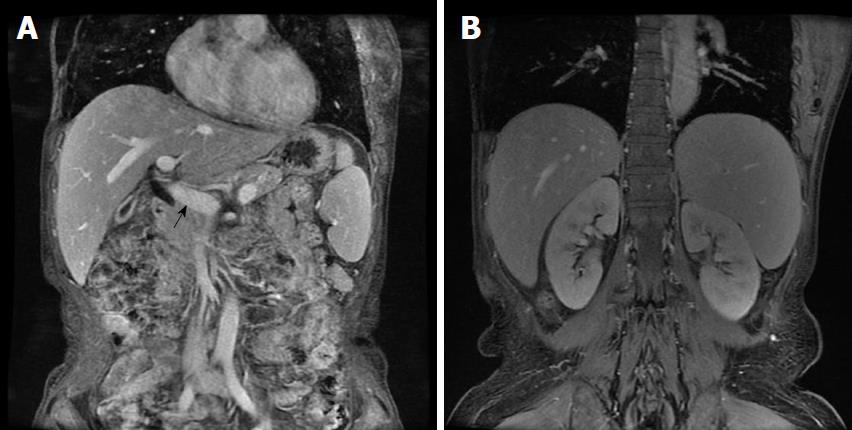

The spectrum of autoimmune liver disease antibodies, hepatitis virus, tumor markers, and ceruloplasmin were negative. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest was normal. Both abdominal ultrasonography (USG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a wide portal vein (diameter 1.5 cm) and splenomegaly (length 15.5 cm) (Figure 1); however, no thrombosis was detected. MRI revealed a heterogeneous hepatic parenchyma signal, which was hyperintense on a T2-weighted image (T2WI). In particular, linear hyperintensity on T2WI was observed around the intrahepatic portal vein. Gastroscopy showed no esophageal or gastric varices. The patient was finally diagnosed with SLE and NCPH, despite her refusal for liver biopsy to confirm histopathology.

She was treated with methylprednisolone 60 mg/d, HCQ 0.4 g/d, metoprolol tartrate 12.5 mg/d and supportive treatment. She responded to this treatment and was discharged following post-treatment examination two weeks later. Her serum albumin (35.4 g/L) was elevated, urinary protein was negative, white cell and platelet counts were normal, hemoglobin was 104 g/L, the clinical features of SLE had disappeared and the dose of methylprednisolone was tapered to 32 mg/d. Abdominal USG reexamination of the patient two months later showed that the portal vein (diameter 1.1 cm) and splenomegaly (length 11.7 cm) had diminished. During the course of treatment, she only took the prescribed medicine and had good tolerance, without obvious adverse or unanticipated events. She was maintained on methylprednisolone 20 mg/d, HCQ 0.4 g/d and metoprolol tartrate 12.5 mg/d.

The clinical details of patients with SLE complicated by NCPH are summarized in Table 1 according to the literature review. A total of 22 cases were reported from 1994 to 2017. The ages of these patients ranged from 19 to 56 years. The longest interval between SLE and NCPH in 15 reported cases was 18 years; the other seven cases were not applicable. SLE complicating other diseases was not observed in 45.5% (10/22) of these cases. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and PCP were observed in 18.2% (4/22) of patients, respectively. No portal thrombosis was detected in any of the patients. Twelve (54.5%) of those patients had hepatic dysfunction according to clinical laboratory tests. During immunological autoantibody measurement, almost all cases (18/22) had a variety of positive autoantibodies, with the exception of four patients. In addition, the majority of patients had nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH, 16/22) or portal fibrosis (PF, 5/22) shown by hepatic histopathology. The SLE therapeutic regimen was mainly composed of glucocorticoids (17/22) to control SLE activity, cyclophosphamide/HCQ for PAH, or methotrexate/cyclosporine for PCP.

SLE is an autoimmune disease involving multiple systems or organs with a variety of clinical presentations, usually characterized by immunological signs and symptoms[17]. Although the liver is not viewed as a common organ targeted by SLE, one third of patients may have alterations in liver function tests[2]. Despite variable causes contributing to liver dysfunction[2], NCPH is rare[3]. NCPH was commonly called NRH or idiopathic portal hypertension in previous reports due to a lack of standardized nomenclature and diagnostic criteria[1]. In general, NCPH is defined as a clinical entity manifesting as intrahepatic portal hypertension in the absence of cirrhosis. NCPH has an unclear etiology and is characterized by portal hypertension, splenomegaly and hypersplenism (anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia). The possibility of an immunologic factor as a potential etiology was raised on the basis that NCPH had been frequently reported in a number of immunologic diseases[1], including SLE, systemic sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis.

The patient described here was diagnosed with the rare condition of SLE complicated by NCPH. The diagnosis of SLE was made based on clinical manifestations and laboratory findings, which were in accordance with the 1978 classification criteria of SLE. In addition, splenomegaly was observed during physical examination upon admission and confirmed by abdominal USG, which also showed a wider portal vein diameter, and by MRI as well (Figure 1). It is known that the normal portal vein diameter is generally no more than 1.1 cm, although increased portal vein diameter is seen in approximatively 30% of individuals. These findings were indicative of the presence of SLE with portal hypertension in this patient. Further investigations were carried out to rule out cirrhosis, including the spectrum of autoimmune liver disease antibodies, hepatitis virus, tumor markers, and ceruloplasmin, all of which were negative. Gastroscopy showed no esophageal or gastric varices and further excluded possible cirrhosis. The patient was diagnosed with active SLE complicated by NCPH according to her clinical features and auxiliary investigations, despite the lack of liver histopathology due to the patient’s refusal for liver biopsy. A limitation of this case is that NCPH was not confirmed by liver biopsy histopathology. Of note, the diagnosis of NCPH was also supported by the patient’s response to treatment. Therefore, in this case, NCPH diagnosed by exclusion was mostly related to SLE itself.

Although more attention in recent years has been paid to NCPH associated with SLE, there is a lack of relevant data in the literature. As shown in Table 1, only 22 cases of NCPH associated with SLE have been reported over the past two decades. In these cases, the major complications were PAH and PCP. However, no portal thrombosis was detected in any of these patients. The pathogenesis of NCPH associated with SLE is thought to be correlated with vasculitis of intrahepatic arteries[18]. Immune complexes deposited in small caliber intrahepatic vessels has been viewed as one of the most attractive theories[3]. PCP may occur as a secondary event linked to splenomegaly and hypersplenism. It has been reported that the occurrence of PAH may be associated with immunological mediation involving impaired cell-mediated immunity and disturbed T4/T8 lymphocyte ratios[4]. In addition, anti-cardiolipin (ACL) antibodies were positive in 38.9% (7/18) of patients. Previous findings showed that portal hypertension profiles, and even esophageal varices, occurred secondary to thrombosis of the portal vein, which was triggered by ACL antibodies[19]. This suggested that thrombosis should be noted in patients with positive ACL antibodies.

In addition to many different types of positive autoantibodies, hepatic disorders were found in more than half of these patients, as shown by laboratory tests. Liver enzymes in patients with NCPH can be normal or slightly abnormal. Rarely, patients may progress to hepatic failure. Abnormal isolated liver enzymes were previously reported in 20% of NCPH cases[20]. Therefore, evidence of non-SLE causes in patients with liver dysfunction is required to be ruled out[3]. Clinically significant hepatic dysfunction is generally unusual, although drug-induced hepatic injury is one of multiple causes in patients with SLE. In the present case, the patient had normal liver enzymes following treatment with HCQ and TGP for two years. Thus, the possibility of drug-induced hepatic injury could be excluded.

NCPH should be suspected in patients with both SLE and portal hypertension in the absence of cirrhosis. Although a definite diagnosis can be established after liver biopsy that shows histologic features consistent with NRH or portal fibrosis, diagnostic imaging, especially MRI, which is more sensitive than CT scan or USG, may be an alternative non-invasive technique[1]. MRI can show signs of portal hypertension and differentiate features commonly seen in cirrhosis[21]. Previous findings[9,10] showed that one part of NCPH appeared hyperintense on T1WI and iso- or hypointense on T2WI; however, other results were conflicting[12]. The use of MRI to enhance diagnostic accuracy is still controversial, and more studies are necessary to further assess the role of MRI.

There is no specific treatment for NCPH associated with SLE to control and prevent symptoms of portal hypertension, especially variceal bleeding. The management strategy for cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension is being used for NCPH with a satisfactory long-term outcome[22]. Glucocorticoids are administered to reduce disease activity in SLE patients. It should be noted that patients suffering from esophageal or gastric varices and taking glucocorticoids may have a higher risk of variceal bleeding. The use of non-selective beta blockers could reduce portal hypertension and its complications[23]. It has been shown that SLE patients with positive antiphospholipid antibodies have a higher risk of thrombotic complications[24]. This suggests that early anticoagulation should be considered in these patients, which may be beneficial and result in a favorable clinical outcome[20]. Some agents, such as steroids and azathioprine, should be avoided. Previous reports indicated that steroid therapy did not prevent the development or progression of portal hypertension[13]. The use of azathioprine has been linked to NCPH[25]. In severe conditions such as variceal bleeding, endoscopic variceal ligation or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting is recommended, in addition to the use of non-selective beta blockers[1].

In conclusion, NCPH, which is a rare under-recognized condition both clinically and pathologically, should be considered in patients with SLE who have clinical manifestations of portal hypertension in the absence of cirrhosis. Immunological dysfunction may be a possible etiology of NCPH. Recognition of early clinical presentation and the associated risk factors of NCPH contribute to a reduction in the missed or delayed diagnosis of this disorder.

A 48 year-old Chinese woman with polyarthritis, irregular fever and trichomadesis was also found to have splenomegaly during physical examination.

The diagnosis of noncirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) was made in the absence of cirrhosis and was associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which was diagnosed based on polyarthritis, pancytopenia, reduced complement 3, multiple positive autoantibodies, a positive Coomb’s test and protein in urine.

Portal hypertension etiology, such as cirrhosis and other obstructive diseases, were considered.

Reduced complement 3, multiple positive autoantibodies, positive Coomb’s test and protein in urine.

Abdominal ultrasonography (USG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated splenomegaly and portal hypertension.

The patient was treated with methylprednisolone, hydroxychloroquine and metoprolol tartrate to reduce SLE disease activity, control portal hypertension and its complications. In severe conditions, such as variceal bleeding, endoscopic variceal ligation or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting is recommended.

NCPH is commonly called nodular regenerative hyperplasia or idiopathic portal hypertension in previous reports due to the lack of standardized nomenclature and diagnostic criteria. Most reported cases of NCPH associated with SLE had severe complications in late stages. In our patient, who was in the early stage of NCPH, splenomegaly and portal hypertension were identified upon physical examination and diagnostic imaging. MRI, which is more sensitive than CT scan or USG, is an alternative non-invasive diagnostic technique that can both reveal signs of portal hypertension as well as differentiate features commonly seen in cirrhosis.

NCPH, which is characterized by portal hypertension, splenomegaly and hypersplenism, should be considered in SLE patients with clinical manifestations of portal hypertension in the absence of cirrhosis. MRI can be performed to rule out cirrhosis. The recognition of early clinical presentation and the associated risk factors of NCPH can contribute to a reduction in missed and delayed diagnosis of this disorder.

CARE Checklist (2013) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2013), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2013).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Manenti A, Sterpetti AV S- Editor: Dou Y L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Song H

| 1. | Lee H, Rehman AU, Fiel MI. Idiopathic Noncirrhotic Portal Hypertension: An Appraisal. J Pathol Transl Med. 2016;50:17-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Takahashi A, Abe K, Saito R, Iwadate H, Okai K, Katsushima F, Monoe K, Kanno Y, Saito H, Kobayashi H. Liver dysfunction in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Intern Med. 2013;52:1461-1465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bessone F, Poles N, Roma MG. Challenge of liver disease in systemic lupus erythematosus: Clues for diagnosis and hints for pathogenesis. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:394-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Woolf D, Voigt MD, Jaskiewicz K, Kalla AA. Pulmonary hypertension associated with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension in systemic lupus erythematosus. Postgrad Med J. 1994;70:41-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Takahaski C, Kumagai S, Tsubata R, Sorachi K, Ozaki S, Imura H, Nakao K. Portal hypertension associated with anticardiolipin antibodies in a case of systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1995;4:232-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sekiya M, Sekigawa I, Hishikawa T, Iida N, Hashimoto H, Hirose S. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver in systemic lupus erythematosus. The relationship with anticardiolipin antibody and lupus anticoagulant. Scand J Rheumatol. 1997;26:215-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nakajima H, Motojima S, Numao T, Fukuda T. A case of idiopathic portal hypertension associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Japanese Journal of Rheumatology. 1999;87-93. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Inagaki H, Nonami T, Kawagoe T, Miwa T, Hosono J, Kurokawa T, Harada A, Nakao A, Takagi H, Suzuki H. Idiopathic portal hypertension associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:235-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Horita T, Tsutsumi A, Takeda T, Yasuda S, Takeuchi R, Amasaki Y, Ichikawa K, Atsumi T, Koike T. Significance of magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver complicated with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report and review of the literature. Lupus. 2002;11:193-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Colmegna I, deBoisblanc BP, Gimenez CR, Espinoza LR. Slow development of massive splenomegaly, portal and pulmonary hypertension in systematic lupus erythematosus: can nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver explain all these findings? Lupus. 2005;14:976-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Park YW, Woo H, Jeong YY, Lee JH, Park JJ, Lee SS. Association of nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver with porto-pulmonary hypertension in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2006;15:686-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Leung VK, Ng WL, Luk IS, Chau TN, Chan WH, Kei SK, Loke TK. Unique hepatic imaging features in a patient with nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver associating with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2007;16:205-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Leung VK, Loke TK, Luk IS, Ng WL, Chau TN, Law ST, Chan JC. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver associated with systemic lupus erythematosus: three cases. Hong Kong Med J. 2009;15:139-142. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Louwers LM, Bortman J, Koffron A, Stecevic V, Cohn S, Raofi V. Noncirrhotic Portal Hypertension due to Nodular Regenerative Hyperplasia Treated with Surgical Portacaval Shunt. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:965304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Guo T, Qian J, Zhu L, Zhou W, Zhu F, Sun G, Fang X. Clinical analysis of 15 cases of liver nodular regenerative hyperplasia. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2012;64:115-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhang X, Liu H, Yao H, Jia Y, Li Z. Systemic lupus erythematosus complicated by noncirrhotic portal hypertention: a clinical analysis and review of literature. Chin J rheumatol. 2017;21:327-332. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Zheng RH, Wang JH, Wang SB, Chen J, Guan WM, Chen MH. Clinical and immunopathological features of patients with lupus hepatitis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126:260-266. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Schlenker C, Halterman T, Kowdley KV. Rheumatologic disease and the liver. Clin Liver Dis. 2011;15:153-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Abraham S, Begum S, Isenberg D. Hepatic manifestations of autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:123-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cazals-Hatem D, Hillaire S, Rudler M, Plessier A, Paradis V, Condat B, Francoz C, Denninger MH, Durand F, Bedossa P. Obliterative portal venopathy: portal hypertension is not always present at diagnosis. J Hepatol. 2011;54:455-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Krishnan P, Fiel MI, Rosenkrantz AB, Hajdu CH, Schiano TD, Oyfe I, Taouli B. Hepatoportal sclerosis: CT and MRI appearance with histopathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:370-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Siramolpiwat S, Seijo S, Miquel R, Berzigotti A, Garcia-Criado A, Darnell A, Turon F, Hernandez-Gea V, Bosch J, Garcia-Pagán JC. Idiopathic portal hypertension: natural history and long-term outcome. Hepatology. 2014;59:2276-2285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schouten JN, Verheij J, Seijo S. Idiopathic non-cirrhotic portal hypertension: a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | de Groot PG, de Laat B. Mechanisms of thrombosis in systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017;31:334-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Musumba CO. Review article: the association between nodular regenerative hyperplasia, inflammatory bowel disease and thiopurine therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1025-1037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |