Published online Nov 6, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i13.641

Peer-review started: July 19, 2018

First decision: July 31, 2018

Revised: September 3, 2018

Accepted: October 23, 2018

Article in press: October 23, 2018

Published online: November 6, 2018

Processing time: 110 Days and 12.4 Hours

To directly visualize Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) by the highly sensitive and specific technique of immunohistochemical staining in colonic tissue from patients newly diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC).

Colonoscopic biopsies from thirty patients with newly diagnosed UC and thirty controls were stained with Giemsa stain and immunohistochemical stain for detection of H. pylori in the colonic tissue. Results were confirmed by testing H. pylori Ag in the stool then infected patients were randomized to receive either anti H. pylori treatment or placebo.

Twelve/30 (40%) of the UC patients were positive for H. pylori by Giemsa, and 17/30 (56.6%) by immunohistochemistry stain. Among the control group 4/30 (13.3%) and 6/30 (20 %) were positive for H. pylori by Giemsa and immunohistochemistry staining respectively. H. pylori was significantly higher in UC than in controls (P = 0.04 and 0.007). All Giemsa positive patients and controls were positive by immunohistochemical stain. Four cases of the control group positive for H. pylori also showed microscopic features consistent with early UC.

H. pylori can be detected in colonic mucosa of patients with UC and patients with histological superficial ulcerations and mild infiltration consistent with early UC. There seems to be an association between UC and presence of H. pylori in the colonic tissue. Whether this is a causal relationship or not remains to be discovered.

Core tip: Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a disease of the colon with an unidentified cause. It has been hypothesized that Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection may play a role in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis due to their comparable immunological features. H. pylori can be detected in colonic mucosa of patients with UC and patients with histological superficial ulcerations and mild infiltration consistent with early UC. There seems to be an association between UC and presence of H. pylori in the colonic tissue. Whether this is a causal relationship or not remains to be discovered.

- Citation: Mansour L, El-Kalla F, Kobtan A, Abd-Elsalam S, Yousef M, Soliman S, Ali LA, Elkhalawany W, Amer I, Harras H, Hagras MM, Elhendawy M. Helicobacter pylori may be an initiating factor in newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis patients: A pilot study. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(13): 641-649

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i13/641.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i13.641

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) of the colon with an unidentified cause. Genetic and environmental elements, in particular the gut bacteria appear to play a role in its development[1]. It has been hypothesized that Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection may play a role in IBD pathogenesis due to their comparable immunological features[2].

The association between H. pylori and UC is subject to much dispute. The impact of bacteria on development of colonic inflammation is supported by the fact that germ-free mice show no signs of bowel inflammation, also among patients with IBD a favorable response may be seen to antibiotic treatment and fecal diversion[3]. On the other hand, some researchers have reported a lower incidence of H. pylori in UC patients than in healthy individuals. This may be explained by the immunopathological characteristics of UC and use of antibiotics, sulphasalazine and 5-aminosalicylic acid[4,5].

Many of the studies on the relation between H. pylori and UC were based on the presence of the organism in the stomach, a positive serology or breath test in patients with UC[6-8].

Regarding detection of H. pylori in UC colonic tissue, most of the studies are based on finding DNA by PCR. The findings could therefore be contested as contaminant DNA could pass to the colon in the faecal stream from food[9].

Therefore we aimed to directly visualize H. pylori by the highly sensitive and specific technique of immunohistochemical staining in colonic tissue from patients newly diagnosed with UC who had not received any prior specific treatments.

This study is a randomized; double blinded, pilot study. A sum of 164 patients referred to the lower endoscopy unit at the Tropical Medicine and Infectious diseases department, Tanta University Hospital; starting from January 2017 till January 2018; were screened for participation in this study.

Inclusion criteria included patients with newly diagnosed UC. Exclusion criteria included patients with contraindication or allergy to any of the drugs included in our study as well as those taking proton pump inhibitors and antibiotics during the 6 wk prior to entry in the trial. Also, pregnant and lactating women and patients suffering from major illnesses such as liver cirrhosis, renal impairment, and gastrointestinal malignancies were excluded from the study.

Diagnosis of UC was based on clinical symptoms, endoscopic and histological findings. Patients without IBD who were undergoing colonoscopy for other reasons and who proved negative for endoscopic findings related to UC were taken as controls. The control group patients were referred to our endoscopy unit for complaints of chronic diarrhea, anemia, abdominal pain, bleeding per rectum, presence of occult blood in stool and anal pain. A full medical history was taken from all participating patients, they were examined clinically, and clinical and demographic data were recorded.

Full length colonoscopy was performed for all patients, using Pentax colonoscopies. Colonoscopic biopsies were obtained from rectal, sigmoid, descending, transverse, ascending colonic, and cecal mucosa of each patient. All colonic endoscopic biopsy specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, processed and cut at 4 μm and used for histological diagnosis and detection of H. pylori.

Histological assessment of the degree of inflammation in UC was evaluated according to Gupta et al[9] as follows: Mild cases were those where lymphocytes and plasma cells expanded the lamina propria, with neutrophilic infiltration of surface/crypt epithelium and/or presence of crypt abscesses in fewer than 50% of crypts. In moderately active cases, inflammation and crypt abscesses were present in above 50% of crypts. Severely active cases were characterized by erosions or ulceration.

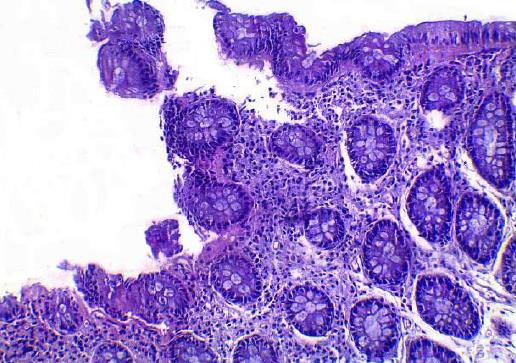

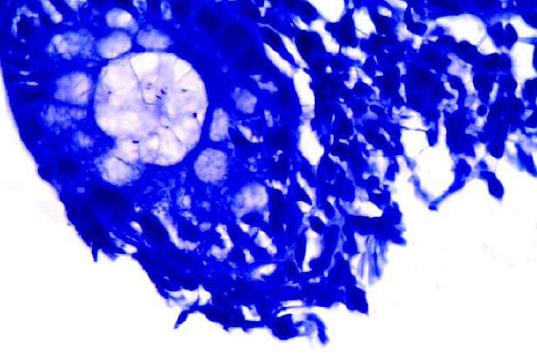

The metachromatic Giemsa solution was added to the slides and allowed to stain for twenty minutes, and then differentiation was performed with a weak acid solution, followed by grades of alcohol. The H. pylori organism appears as spiral-shaped, rods or coccoid forms stained with blue color, and the background has varying shades of pink and pale blue color[10].

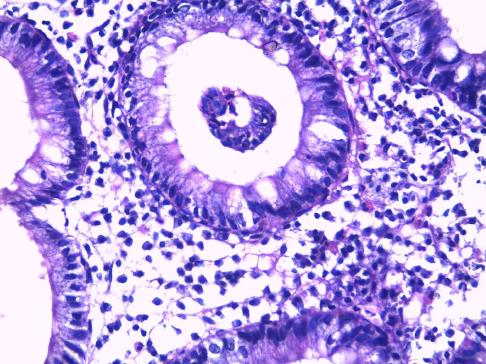

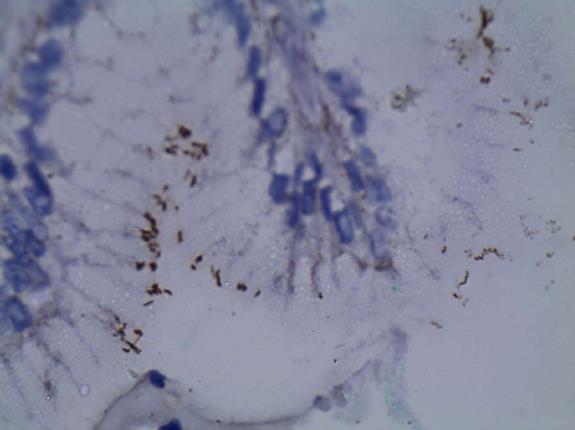

Tissue sections were stained with immunohistochemical stain using a polyclonal antibody directed against the whole H. pylori organism (Rabbit polyclonal antibody (Thermo scientific ready to use staining®). Negative controls were sections treated as above, but instead of incubation with the primary antibody, they were incubated with 1% bovine serum albumin/PBS. The H. pylori organism appeared as spiral-shaped, rods or coccoid forms stained with a brown color.

Monoclonal antibody testing for H. pylori Ag in stool was performed for confirmation following detection of the organism in colonic tissue by both Giemsa and Immunohistochemical methods.

Testing for H. pylori antigen in the stool was done to confirm infection and to assess cure after therapy. Successful eradication of H. pylori was confirmed by a negative result 4 wk after the end of treatment.

Fresh fecal samples were collected into stool sample collection containers. It is required to collect a minimum of 1-2 mL liquid stool sample or 1-2 g solid sample. The collected fecal sample was transported to the lab in a frozen condition (-20 °C). If the stool sample was collected and tested the same day, it is allowed to be stored at 2 °C-8 °C.

H. pylori stool Ag was measured with enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (catalogue no. HPY35-k01, Eagle Biosciences, Inc., United States) by sandwich technique and the color change was measured spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Patients with UC and positive for H. pylori by immunohistochemistry staining and H. pylori antigen in the stool were randomly assigned to receive either triple therapy for H. pylori or placebo for 2 wk plus mesalazine 4 g daily. The recruited patients were randomized utilizing a computerized random number generator to select randomly permuted blocks and an equal allocation ratio. To ensure concealment; envelopes which were sequentially numbered, opaque and sealed were utilized. Elkhalawany W and Soliman S recruited and enrolled participants. The treatment administered was not known for both the investigators and the patients. The received treatment and placebo were identical in labeling and appearance. Compliance was determined through asking the patients and recovery of empty medication envelopes.

Patients were randomized into two groups: Group I: patients receiving triple anti H. pylori drugs including clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily, amoxicillin 500 mg twice daily and omeprazole 40 mg twice daily for 2 wk and Group II: patients receiving placebo for 2 wk. Both groups received mesalazine 4 g daily.

Before starting the trial, the study received approval by the institutional Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University (code approval No: 30640/12/15). This trial was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02423395).

Baseline evaluation included thorough history taking, full clinical examination and laboratory testing. All patients were followed weekly during the period of treatment. Patients’ were called weekly through their telephone numbers and were asked about the frequency, and severity of motions and if any side effects for the assigned treatment occurred during the previous week. After the end of therapy testing for H. pylori antigen in stool was done to assess cure.

The primary outcome of the trial was the number of patients with UC who achieved remission at the end of 2 wk of triple therapy for H. pylori. The secondary outcome was the prevalence of H. pylori in patients newly diagnosed with UC.

Results were collected, tabulated and statistically analyzed by an IBM compatible personal computer with SPSS statistical package version 20 (SPSS Inc. released 2011. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 20.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp., United States). Student’s t-test is of significance was performed to compare quantitative variables between two groups of normally distributed data, while Mann Whitney’s test was performed to compare quantitative variables between two groups of abnormally distributed data. χ2 test was performed to examine association between qualitative variables., Fischer’s Exact test with Yates correction was used when cells were fewer than five. Z test was used to compare two proportions in two groups. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

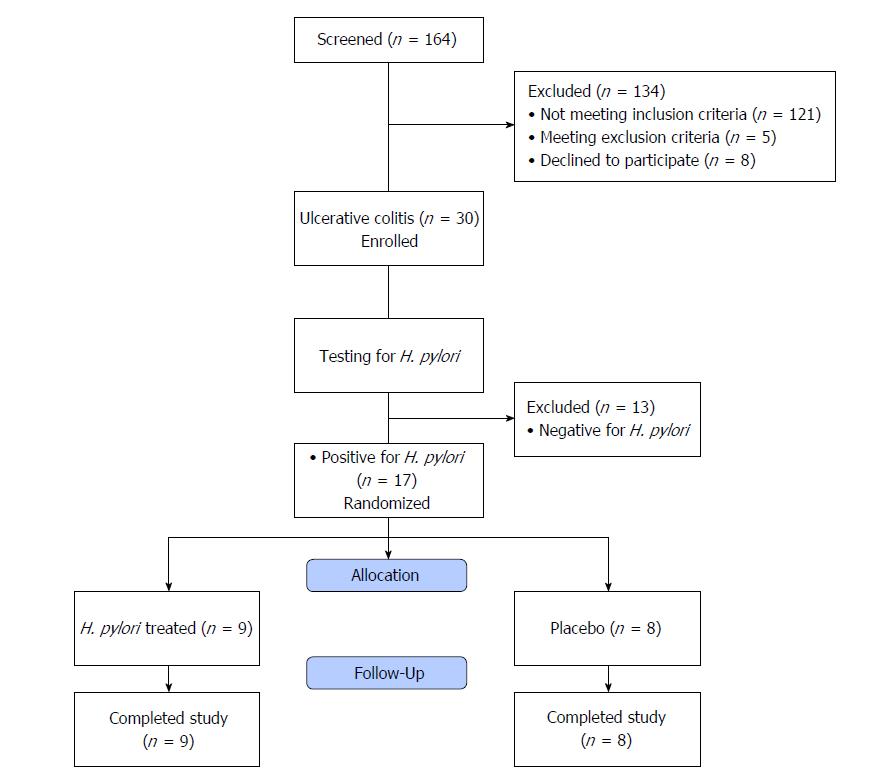

In sum, 164 patients were screened for study participation. One hundred and thirty-four patients were excluded from the study. One hundred and twenty-one patients did not fulfill the inclusion criteria, 5 fulfilled the exclusion criteria and 8 declined to participate. Thus, 30 patients with newly diagnosed UC were enrolled in this study. They were 18 males and 12 females; their mean age was 38.9 ± 14.7 years (Figure 1).

Thirty patients without IBD who were undergoing colonoscopy for other reasons and who proved negative for endoscopic findings related to UC were taken as controls. They were 20 males and 10 females, their mean age was 49.4 ± 4.1 years.

Clinical manifestations of all participants in the study are demonstrated in Table 1. Patients with UC had significantly higher rates of abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, chronic non-bloody diarrhea, fatigue, tenesmus and anemia than those in the control group. Laboratory investigations of the studied groups are shown in Table 2. Patients with UC had significantly lower hemoglobin concentrations and platelet count but higher WBC counts than those of the control group. Both 1st and 2nd hour erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) levels were significantly higher in UC patients. None of the patients included in the study had any gastric complaints and therefore upper GI endoscopy was not performed.

| Clinical manifestations | Ulcerative colitis (n = 30) | Control (n = 30) | P value |

| Abdominal pain | 26 (86.6) | 20 (66.6) | 0.120 |

| Bloody diarrhea | 24 (80) | 0 (0) | < 0.001a |

| Chronic non bloody diarrhea | 6 (20) | 22 (73.3) | < 0.001a |

| Fatigue | 16 (53.3) | 5 (16.6) | 0.006a |

| Tenesmus | 20 (66.6) | 5 (16.6) | < 0.001a |

| Bleeding per rectum | 0 (0) | 8 (26.6) | 0.007a |

| Constipation | 0 (0) | 4 (13.3) | 0.120 |

| Rectal pain | 2 (6) | 5 (16.6) | 0.420 |

| Anemia | 24 (80) | 9 (30) | 0.001a |

| Ulcerative colitis (n = 30) mean ± SD | Control (n = 30) mean ± SD | P value | ||

| CBC | HB g/dL | 9.52 ± 3.44 | 11.42 ± 2.02 | 0.010a |

| Platelets 10³/mL | 140.62 ± 83.91 | 195.7 ± 87.23 | 0.004a | |

| WBC cells/mL | 8.65 ± 4.25 | 4.35 ± 2.58 | < 0.001a | |

| Liver functions | Bilirubin mg/dL | 0.84 ± 0.41 | 0.75 ± 0.38 | 0.380 |

| Albumin g/dL | 3.24 ± 1.42 | 3.82 ± 1.31 | 0.100 | |

| AST IU/L | 26.01 ± 12.00 | 21.1 ± 10.1 | 0.090 | |

| ESR | 1st h | 37.20 ± 18.10 | 15.03 ± 7.41 | < 0.001a |

| 2nd h | 46.12 ± 19.32 | 23.41 ± 9.13 | < 0.001a |

Colonoscopy for the 30 patients of the control group proved unremarkable for 22 patients, revealed internal piles in 7 patients and a rectal polyp in one. Among the control group; 14 patients (46.67%) had a normal mucosal appearance, while 11 (36.66%) proved to have microscopic findings of chronic non-specific colitis, 5 patients (16.66%) had early microscopic features of UC in the form of superficial ulcerations and mild infiltration.

Among the UC group patients 12/30 (40%) of the patients were positive for H. pylori by Giemsa staining, whereas 17/30 (56.6%) were positive for H. pylori by immunohistochemistry stain confirmed by testing H. pylori Ag in the stool.

In the control group 4/30 patients (13.33%) of the patients were positive for H. pylori by Giemsa staining (Figures 2 and 3), whereas 6/30 (10%) were positive for H. pylori by immunohistochemistry stain, yet even though the yield of immunohistochemical staining was higher than with Giemsa staining, this did not reach statistical significance (Table 3, Figures 4 and 5). Both Giemsa and immunohistochemical stains had significantly higher positive results for H. pylori in UC group than the control group (P = 0.04 and P = 0.007 respectively (Table 4).

| Detection of H. pylori | |||

| Ulcerative colitis | Control | ||

| Giemsa stain | Immunohistochemical stain | Giemsa stain | Immunohistochemical stain |

| 12/30 (40%) | 17/30 (56.6%) | 4/30 (13.3%) | 6/30 (20%) |

| P = 0.30 | P = 0.72 | ||

It was interesting to note that 4 of the control cases that proved to have H. pylori showed microscopic features consistent with early UC even though there was no evidence of this on endoscopy. Those 4 patients were advised for follow up programme. All Giemsa positive patients were positive by immunohistochemical staining for H. pylori. Histopathological diagnosis in relation to H. pylori staining in the control group patients is demonstrated in Table 5. Patients with UC and positive for H. pylori (n = 17) were randomly assigned to receive either triple therapy for H. pylori (n = 9) or placebo (n = 8) for 2 wk (Figure 1).

| Histopathological diagnosis | Giemsa stain | Immunohistochemical stain | ||

| H. pylori positive (n = 4) | H. pylori negative (n = 26) | H. pylori positive (n = 6) | H. pylori negative (n = 24) | |

| Normal | 0 | 14 | 0 | 14 |

| 14/30 (46.67%) | ||||

| Chronic nonspecific colitis | 1 | 10 | 2 | 7 |

| 11/30 (36.66%) | ||||

| Early microscopic features of UC | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| 5/30 (16.66%) | ||||

There were no significant differences in baseline ESR, C reactive protein (CRP), and number of motions per day between the H. pylori treated and the placebo group (P > 0.05). In the H. pylori treated group, ESR, CRP, and number of motions per day were significantly decreased after 2 wk of therapy when compared to baseline (P < 0.001). Two patients out of 9 still had blood streaks in stool after 2 wk of therapy. There was no significant change following treatment with placebo (Table 6). The regimen was well tolerated by all patients and mild side effects were reported in 1 patient who had nausea. All patients in the H. pylori treated group had negative H. pylori antigen in stool 4 wk after the end of therapy.

| H. pylori treated (n = 9) | Placebo (n = 8) | |||||

| Parameters | Baseline | After 2 wk | P-value | Baseline | After 2 wk | P-value |

| ESR (1st) | 38.56 ± 9.81 | 22.33 ± 5.55 | < 0.001 | 37.50 ± 7.82 | 32.75 ± 6.34 | 0.203 |

| ESR (2nd) | 64 (54.25-73.25) | 32 (30.5-37.5) | < 0.001 | 65.63 ± 11.51 | 58.75 ± 9.33 | 0.211 |

| CRP | 24 (22.5-36) | 12 (6-12) | 0.001 | 25.75 ± 9.29 | 24.12 ± 9.68 | 0.737 |

| No. of motions per day | 8 (6.75-9) | 3 (2-3.25) | < 0.001 | 7.63 ± 1.41 | 6.88 ± 1.64 | 0.343 |

The role of H. pylori in IBD is a subject of much study and remains unresolved as yet. A number of studies have suggested that H. pylori infection plays a role in protection from occurrence of IBD[11,12]. Sonnenberg and Genta[13] in 2012 reported that presence of the organism in the stomach had an inverse association with IBD. There is much diversity among these studies, and most of the mare dependent on detection of the organism in gastric biopsies, breath test analysis or serum antibody testing.

On the other hand some studies have indicated a link between IBD and H. pylori; H. pylori was detected in 36.7% of IBD patients using a biopsy urease test and 30% using H and E staining of colonic tissue from IBD patients[14]. Streutker et al[15] detected H. pylori ribosomal DNA in colonic tissue from 5 of 33 (15.15%) UC patients. Multiple techniques for H. pylori detection in colonic tissue are available; the hematoxylin and eosin stain has been found to be the most unreliable for diagnosis of H. pylori infection[16].

Giemsa staining for H. pylori detection is well known to be a reliable, easy to perform and inexpensive technique to detect the spiral forms and therefore is usually considered as the stain of choice[17]. Immunohistochemistry is more precise in diagnosis as it uses an anti H. pylori antibody that reacts with the somatic antigens of the whole organism and can detect low density infections as well as non spiral coccoid forms of the organism which are non culturable and very difficult to detect[18-21].

H. pylori is highly prevalent in Egypt with rates of up to 88% in the normal population, making use of the urea breath test or ELISA of no benefit to our study[22-24]. Studies utilizing PCR PCR-only studies can be criticized as there is a possibility that contaminant environmental DNA transited to the colon from food could affect the results[9].

Therefore we aimed at directly visualizing the organism in colonic tissue using the two most reliable methods, Giemsa staining and immunohistochemical staining for H. pylori. We studied patients newly diagnosed with UC who had not previously received 5-aminosalicylates or sulphasalazine as it has been suggested in studies on gastric infection that they block adhesion of H. pylori to the mucosa and inhibit replication of the bacterium[25,26].

In our UC patients, H. pylori was detected in 12/30 (40%) by Giemsa staining, and 17/30 (56.6%) by immunohistochemistry stain. This was significantly higher than among our controls of whom 4/30 (13.3%) proved to have H. pylori in their colonic biopsies by Giemsa staining and 6/30 (20%) by immunohistochemical staining (P = 0.04 and P = 0.007 respectively) and indicates a possible link between H. pylori and UC.

These numbers are much lower than those of H. pylori prevalence in the Egyptian population and therefore do not reflect the prevalence of H. pylori in general. We believe the link between the two conditions to be logical as focal cryptitides are usually associated with H. pylori infection and they are characteristic of UC too[8]. The main pathological features of UC are continuous, superficial inflammation of the colorectal mucosa, with cryptitides and crypt abscesses[27].

In the control group of our study, four of the six cases in whom H. pylori was detected had a pathological pattern resembling early UC in the form of superficial ulcerations and mild infiltration raising the question of the possible effect of the infection on colonic tissue by inducing a local inflammatory response.

The chronic inflammation in UC could be caused by increased cellular production of nitric oxide (NO) in response to the H. pylori lipopolysaccharide as well as direct mucosal damage caused by urease and cytotoxins. Platelet activation and aggregation can lead to formation of microthrombi epithelium causing infarction and development of ulcers[28-30].

In our study, immunohistochemistry appeared to be a more reliable technique for tissue diagnosis of H. pylori infections there were more cases diagnosed by immunohistochemical staining than Giemsa; 56.6% vs 40% in the UC group (P = 0.30) and 20% vs 13.3% among the control cases (P = 0.72), however the difference did not reach statistical significance.

H. pylori can be detected in colonic mucosa of patients with UC and patients with histological superficial ulcerations and mild infiltration consistent with early UC. There seems to be an association between UC and presence of H. pylori in the colonic tissue. Whether this is a causal relationship or not remains to be discovered.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) of the colon with an unidentified cause. Genetic and environmental elements, in particular the gut bacteria appear to play a role in its development. It has been hypothesized that Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection may play a role in IBD pathogenesis due to their comparable immunological features.

The association between H. pylori and UC is subject to much dispute. The impact of bacteria on development of colonic inflammation is supported by the fact that germ free mice show no signs of bowel inflammation, also among patients with IBD a favorable response may be seen to antibiotic treatment and faecal diversion.

To directly visualize H. pylori by the highly sensitive and specific technique of immunohistochemical staining in colonic tissue from patients newly diagnosed with UC.

Colonoscopic biopsies from thirty patients with newly diagnosed UC and thirty controls were stained with Giemsa stain and immunohistochemical stain for detection of H. pylori in the colonic tissue. Results were confirmed by testing H. pylori Ag in the stool then infected patients were randomized to receive either anti H. pylori treatment or placebo.

Twelve/30 (40%) of the UC patients were positive for H. pylori by Giemsa, and 17/30 (56.6%) by immunohistochemistry stain. Among the control group 4/30 (13.3%) and 6/30 (20%) were positive for H. pylori by Giemsa and immunohistochemistry staining respectively. H. pylori was significantly higher in UC than in controls (P = 0.04 and 0.007). All Giemsa positive patients and controls were positive by immunohistochemical stain. Four cases of the control group positive for H. pylori also showed microscopic features consistent with early UC.

H. pylori can be detected in colonic mucosa of patients with UC and patients with histological superficial ulcerations and mild infiltration consistent with early UC. There seems to be an association between UC and presence of H. pylori in the colonic tissue. Whether this is a causal relationship or not remains to be discovered.

There seems to be an association between UC and presence of H. pylori in the colonic tissue. Whether this is a causal relationship or not remains to be discovered.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Fujimori S, Tarnawski AS S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Song H

| 1. | Oliveira AG, das Graças Pimenta Sanna M, Rocha GA, Rocha AM, Santos A, Dani R, Marinho FP, Moreira LS, de Lourdes Abreu Ferrari M, Moura SB. Helicobacter species in the intestinal mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:384-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Papamichael K, Konstantopoulos P, Mantzaris GJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and inflammatory bowel disease: is there a link? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6374-6385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Dotan I, Mayer L. Immunopathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2002;18:421-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wu XW, Ji HZ, Yang MF, Wu L, Wang FY. Helicobacter pylori infection and inflammatory bowel disease in Asians: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4750-4756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Triantafillidis JK, Gikas A, Apostolidiss N, Merikas E, Mallass E, Peros G. The low prevalence of helicobacter infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease could be attributed to previous antibiotic treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1213-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jin X, Chen YP, Chen SH, Xiang Z. Association between Helicobacter Pylori infection and ulcerative colitis--a case control study from China. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10:1479-1484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lord AR, Simms LA, Hanigan K, Sullivan R, Hobson P, Radford-Smith GL. Protective effects of Helicobacter pylori for IBD are related to the cagA-positive strain. Gut. 2018;67:393-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Parente F, Cucino C, Bollani S, Imbesi V, Maconi G, Bonetto S, Vago L, Bianchi Porro G. Focal gastric inflammatory infiltrates in inflammatory bowel diseases: prevalence, immunohistochemical characteristics, and diagnostic role. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:705-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gupta RB, Harpaz N, Itzkowitz S, Hossain S, Matula S, Kornbluth A, Bodian C, Ullman T. Histologic inflammation is a risk factor for progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1099-1105; quiz 1340-1341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 617] [Cited by in RCA: 570] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gray SF, Wyatt JI, Rathbone BJ. Simplified techniques for identifying Campylobacter pyloridis. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39:1279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Luther J, Dave M, Higgins PD, Kao JY. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis and systematic review of the literature. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1077-1084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rokkas T, Gisbert JP, Niv Y, O’Morain C. The association between Helicobacter pylori infection and inflammatory bowel disease based on meta-analysis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:539-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sonnenberg A, Genta RM. Low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:469-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Farhan SS, Al-Khazraji KA, Al-Khafaji FA, Al-Khateeb HM, Al-Kassam ZQ. Study of H. Pylori in a Group of Iraqi Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (Histological and Molecular Study). IPMJ. 2012;11:734-741. |

| 15. | Streutker CJ, Bernstein CN, Chan VL, Riddell RH, Croitoru K. Detection of species-specific helicobacter ribosomal DNA in intestinal biopsy samples from a population-based cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:660-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Molyneux AJ, Harris MD. Helicobacter pylori in gastric biopsies--should you trust the pathology report? J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1993;27:119-120. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Rotimi O, Cairns A, Gray S, Moayyedi P, Dixon MF. Histological identification of Helicobacter pylori: comparison of staining methods. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:756-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wabinga HR. Comparison of immunohistochemical and modified Giemsa stains for demonstration of Helicobacter pylori infection in an African population. Afr Health Sci. 2002;2:52-55. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Tajalli R, Nobakht M, Mohammadi-Barzelighi H, Agah S, Rastegar-Lari A, Sadeghipour A. The immunohistochemistry and toluidine blue roles for Helicobacter pylori detection in patients with gastritis. Iran Biomed J. 2013;17:36-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Azevedo NF, Almeida C, Cerqueira L, Dias S, Keevil CW, Vieira MJ. Coccoid form of Helicobacter pylori as a morphological manifestation of cell adaptation to the environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:3423-3427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Thomson JM, Hansen R, Berry SH, Hope ME, Murray GI, Mukhopadhya I, McLean MH, Shen Z, Fox JG, El-Omar E. Enterohepatic helicobacter in ulcerative colitis: potential pathogenic entities? PLoS One. 2011;6:e17184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mohammad MA, Hussein L, Coward A, Jackson SJ. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among Egyptian children: impact of social background and effect on growth. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11:230-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bassily S, Frenck RW, Mohareb EW, Wierzba T, Savarino S, Hall E, Kotkat A, Naficy A, Hyams KC, Clemens J. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori among Egyptian newborns and their mothers: a preliminary report. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:37-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Salem OE, Youssri AH, Mohammad ON. The prevalence of H. pylori antibodies in asymptomatic young egyptian persons. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 1993;68:333-352. [PubMed] |

| 25. | el-Omar E, Penman I, Cruikshank G, Dover S, Banerjee S, Williams C, McColl KE. Low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in inflammatory bowel disease: association with sulphasalazine. Gut. 1994;35:1385-1388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Stenson WF, Mehta J, Spilberg I. Sulfasalazine inhibition of binding of N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (FMLP) to its receptor on human neutrophils. Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;33:407-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Martland GT, Shepherd NA. Indeterminate colitis: definition, diagnosis, implications and a plea for nosological sanity. Histopathology. 2007;50:83-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chin MP, Schauer DB, Deen WM. Prediction of nitric oxide concentrations in colonic crypts during inflammation. Nitric Oxide. 2008;19:266-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Smoot DT, Mobley HL, Chippendale GR, Lewison JF, Resau JH. Helicobacter pylori urease activity is toxic to human gastric epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1992-1994. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Elizalde JI, Gómez J, Panés J, Lozano M, Casadevall M, Ramírez J, Pizcueta P, Marco F, Rojas FD, Granger DN. Platelet activation In mice and human Helicobacter pylori infection. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:996-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |