Published online Jun 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i6.235

Revised: March 26, 2014

Accepted: April 17, 2014

Published online: June 16, 2014

Processing time: 128 Days and 15 Hours

We present a case of an elderly man, who initially presented with right facial nerve palsy, ipsilateral headache, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and no fever. A presumptive diagnosis of giant cell arteritis was made and the patient was treated with high-dose steroids. A temporal artery biopsy was negative. Several months later, while on 16 mg of methylprednisolone daily, he presented with severe sensorimotor peripheral symmetric neuropathy, muscle wasting and inability to walk, uncontrolled blood sugar and psychosis. A work-up for malignancy was initiated with the suspicion of a paraneoplastic process. At the same time a biopsy of the macular skin lesions that had appeared on the skin of the left elbow and right knee almost simultaneously was inconclusive, whereas a repeat biopsy from the same area of the lesions that had become nodular, a month later, was indicative of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Finally, a third biopsy of a similar lesion, after spreading of the skin process, confirmed the diagnosis of Kaposi’s sarcoma. He was treated with interferon α and later was seen in very satisfactory condition, with no clinical evidence of neuropathy, normal muscle strength, no headache, normal electrophysiologic nerve studies, involution of Kaposi’s lesions and a normal ESR.

Core tip: We present a case of an elderly man, who initially presented with right facial nerve palsy, ipsilateral headache, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and no fever. A presumptive diagnosis of giant cell arteritis was made and the patient was started on high-dose steroids. Several months later, he presented with severe sensorimotor peripheral symmetric neuropathy. A biopsy of the macular skin lesions that had appeared almost simultaneously, was suggestive of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Although peripheral and cranial nerve involvement has not been reported in Kaposi’s sarcoma, we postulate that the patient’s condition could be attributed to that, within the context of a paraneoplastic process

- Citation: Daoussis D, Chroni E, Tsamandas AC, Andonopoulos AP. Facial nerve palsy, headache, peripheral neuropathy and Kaposi’s sarcoma in an elderly man. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(6): 235-239

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i6/235.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i6.235

We present herein an interesting case of an elderly patient with right facial nerve palsy, ipsilateral headache, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), sensorimotor neuropathy and Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Dimitrios Daoussis, MD: The patient was a 72-year-old white man, who was initially admitted on September 16, 2009 to the department of neurology, with chief complaint of severe persistent right sided headache. Twenty days prior to admission, he experienced acutely right facial nerve palsy of peripheral type. Ten days later he developed severe right temporal headache, and was started on prednisolone 25 mg/d by oral administration (po) advised by a neurologist. He had noticed gradual impairment of hearing acuity since four months ago. Glaucoma had been present for the last three years, and right eye blindness for ten years, due to an accident. There was no fever, and except for right peripheral facial nerve palsy, physical examination was unremarkable. Laboratory examination revealed a hematocrit of 35.1% with mean corpuscular volume 93.4, a white blood cell (WBC) count of 12700/μL, a platelet count of 372 000/μL and a markedly elevated ESR of 105 mm/h. All biochemical parameters and his serologic profile, including rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, complement (C3 and C4) and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) were within the normal range. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scans were normal. Otolaryngologic evaluation suggested bilateral adhesive otitis, whereas ophthalmologic examination confirmed the presence of glaucoma and the right side blindness. The patient was started on methylprednisolone 48 mg/d po, with the presumptive diagnosis of giant cell arteritis (GCA). He was discharged on this regimen on September 24, 2009, pending the result of a right temporal artery biopsy, performed on the day of discharge.

He was first seen at the rheumatology outpatient clinic three months later, on December 20, 2009, again complaining of right temporal headache, despite of having been taking methylprednisolone 40 mg/d. The report of the temporal artery biopsy was negative for GCA and steroid tapering was started.

On February 23, 2010, he reported deterioration of his headaches, whereas his ESR was 58 mm/h. Methylprednisolone dose was increased back to 32 mg/d, and on March 22, 2010, his ESR had dropped to 6 mm/h and headaches had improved. Gradual tapering of steroids was again undertaken and an appointment after two months was given.

The patient was admitted to the department of medicine on June 26, 2010 with fatigue, profound muscle weakness, inability to walk and psychosis. While on methylprednisolone 16 mg/d, his admission glucose was 665 mg/dL, whereas it had been always normal before. He was afebrile without headache. He was profoundly wasted, with severe proximal muscle weakness and decreased deep tendon reflexes. The right facial nerve palsy had improved. Two bluish-red macules, about 1.5 cm in diameter, were noticed over the skin of the right knee and left elbow, respectively. Laboratory tests revealed a hematocrit of 29.8%, mild leukocytosis, normal platelet count, an ESR of 28 mm/h, potassium of 3.73 mg%, sodium of 136 mg%, calcium of 8.64 mg%, magnesium of 1.5 mg%, creatinine of 0.6 mg%, total serum protein of 5 g% with albumin 2 g%, and normal creatine phosphokinase, transaminases, alkaline phosphatase and normal urinalysis. Serologic profile for rheumatic diseases and A, B and C hepatitis was unrevealing. Serum angiotensin converting enzyme (SACE) level was normal. A chest X-ray was also normal. An electrophysiologic evaluation was compatible with mixed sensorimotor neuropathy, worse on the lower extremities, but no myositis was found, except for changes due to chronic steroid administration. Cerebrospinal fluid examination was normal. Proximal muscle biopsy did not disclose myositis, vasculitis or granuloma. A purified protein derivative skin test was negative. Thyroid function was also normal.

With the suspicion of an underlying occult malignancy, an extensive work- up towards that direction was initiated; gastroscopy, barium enema, brain, thoracic and abdominal CT scans, thyroid ultrasound and cancer indices including alpha fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA 19-9, prostatic specific antigen, beta horionic gonadotrophin were all normal. A biopsy of the left elbow skin lesion displayed atypical changes (see pathological description below).

With the patient’s condition deteriorating, both clinically and in laboratory test results (Ht = 20.3%, ESR = 70 mm/h), with uncontrolled blood sugar levels, and cushingoid features, including psychosis and severe muscle wasting, in an attempt to spare steroids, we treated the patient with methotrexate 7.5 mg/wk. His condition improved and on July 24, 2000, one month after his admission, he was discharged on the above methotrexate dose, methylprednisolone 16 mg/d and insulin, to be followed closely.

On the August 23 appointment, the patient’s general condition was relatively satisfactory, with significant improvement of his muscle strength, and a hematocrit of 36.6% and ESR 15 mm/h. However, the previously noted macules on the skin of the left elbow and right knee had become nodular and a biopsy of the lesion of the elbow was taken. This biopsy was indicative of Kaposi’s sarcoma, although not typical. One month later, on September 27, the patient returned with similar bluish-red nodules all over his body, typical of Kaposi’s sarcoma, and a third biopsy confirmed the diagnosis. The methotrexate was discontinued and the patient was admitted on October 5, 2000 to the dermatology service and started on interferon α (IFNα-2α) treatment. At that time, his hematocrit was 35% and ESR 25 mm/h, whereas serology for HIV was negative. An electrophysiologic nerve study showed definite improvement of the neuropathy. He was discharged on November 18, 2000, on IFNα and methylprednisolone 16 mg/d.

On January 9, 2011 at his outpatient visit, he was found in very good condition, with normal muscle strength and gait, very mild right temporal headache, no psychotic features, with normal deep tendon reflexes, and with only pale-brownish skin macules, remnants of involuted previous nodular lesions. A third electrophysiologic study showed further improvement of the neuropathy, and the patient was put to regular follow-up.

Elisabeth Chroni, MD, PhD: The findings were consistent with distal sensorimotor neuropathy of mixed-axonal and demylinating-type. On follow-up studies 5 and 7 mo later, a gradual improvement was observed.

Electromyography of facial muscles showed denervation potentials (fibrillations and positive waves) at rest and poor recruitment of motor units indicating axonal damage of facial nerve. All the above are depicted in Table 1.

| Nerve | Parameter | 1st study | 2nd study | 3rd study | Normal limits |

| Motor conduction | |||||

| Median | CV (ms) | 46 | 60 | 60 | ≥ 50 |

| CMAP (mV) | 4 | 6 | 6 | ≥ 5 | |

| Min F-wave (ms) | 32 | 28 | 27 | ≤ 30 | |

| Peroneal | CV (ms) | 35 | 40 | 43 | ≥ 41 |

| CMAP (mV) | 0.4 | 1 | 2 | ≥ 2 | |

| Min F-wave (ms) | - | - | 54 | ≤ 52 | |

| Sensory conduction | |||||

| Sural | CV (ms) | - | - | 32 | ≥ 40 |

| SAP (μV) | - | - | 4 | ≥ 8 | |

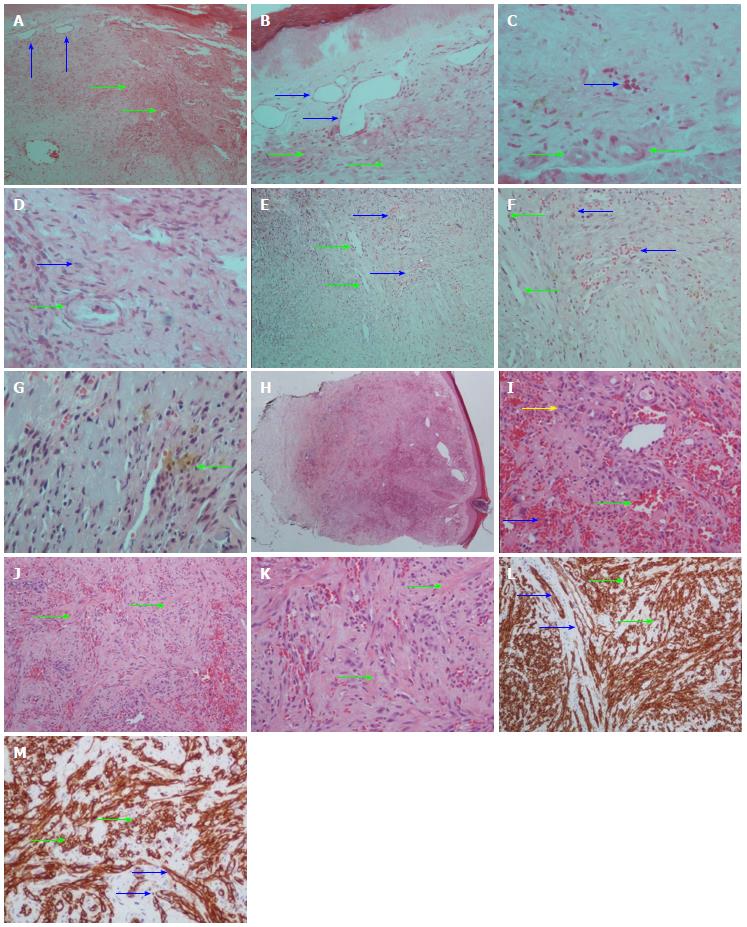

Athanassios C Tsamandas, MD: The first biopsy revealed areas with proliferation of fibroblasts and capillaries, in the dermis (Figure 1A-D). The vessels of medium size displayed fibrosis of the wall, luminal narrowing and elastic lamina disruption without any fibrin deposition.

The second biopsy (Figure 1E-G) was consistent with early changes of Kaposi’s sarcoma (macular-patch stage).

The third biopsy (Figure 1H-M) showed a well-defined nodule composed of vascular spaces and spindle cells that replaced the dermal collagen. Spindle cells and endothelial cells lining the vascular clefts were CD34 (+). A diagnosis of Kaposi’s sarcoma was made.

Retrospectively, the slides were reviewed and the features in the first biopsy were suggestive of a very early Kaposi’s sarcoma lesion.

Andrew P Andonopoulos, MD, FACP: It would be simplistic to guess that our patient had a Bell’s palsy, independent of the neuropathy he later developed, and the malignancy which appeared almost concomitantly with the latter. The facial nerve palsy and the headache, along with the impressively elevated ESR, speak against the possibility of idiopathic Bell’s palsy. Furthermore, the patient had no hypertension or diabetes. The psychotic episode that our patient suffered was probably associated with the iatrogenic Cushing.

Similarly, the whole picture and its evolution are against the possibility of a metabolic or toxic cause of the neurologic syndrome in our patient. Instead, it would be very suggestive of a vasculitic process, if not related to a paraneoplastic syndrome, due to the malignancy, which appeared almost simultaneously with the peripheral neuropathy.

At a first glance, there was a very strong diagnostic possibility of GCA at the time of the initial presentation of this elderly gentleman, with temporal headache and an impressively elevated ESR. The negative biopsy, despite the fact that the specimen was meticulously examined and even recut later, does not rule out this possibility, because the procedure is not 100% sensitive[1]. However, one could argue that the response of the headache to the treatment was not the one typically expected in GCA, as it was mentioned. The apparent response of the ESR to steroid administration, does not necessarily mean that the elevated ESR was secondary to GCA, because similar responses may be encountered in several vasculitic or even other different processes. Furthermore, the development of neuropathy secondary to GCA, on steroid treatment, would be unusual. Peripheral neuropathy has been described in GCA as a rather rare manifestation, coincident with clinically active disease. In a study by Caselli et al[2] out of 166 consecutive patients with GCA, 23 had clinical evidence of peripheral neuropathic disease, of whom 11 had a generalized peripheral neuropathy, nine had mononeuritis multiplex and three had a mononeuropathy. Only a few reports of facial nerve palsy in the context of GCA appear in the literature[3-7].

Wegener’s granulomatosis is, among the vasculitides, the one that can involve most commonly cranial nerves, besides causing peripheral neuropathy[8]. Our patient had no features of Wegener’s granulomatosis, without upper airway, lung or kidney involvement, and negative ANCA.

Polyarteritis nodosa would be another remote possibility, but the absence of fever, hypertension and kidney involvement, along with the negative, for vasculitis, muscle biopsy argue against this possibility[9]. Churg-Strauss syndrome could not account for our patient’s picture, because the hallmarks of this entity were absent[10].

Isolated granulomatous vasculitis of the central nervous system could have been another possibility. The advanced age of our patient, the impressively high ESR, and especially the normal brain MRI and cerebrospinal fluid argue strongly against this diagnosis[11]. Finally, our patient had no evidence of sarcoidosis, with normal chest X-ray, normal SACE and negative for non-caseating granuloma muscle biopsy.

Keeping all the above considerations in mind, one then should try to correlate the patient’s manifestations with the malignant disease which he was found to have.

Axonal peripheral neuropathy, such as this patient had, can be a feature of a paraneoplastic syndrome, shared by several malignancies, mainly of the lung, but of other organs as well. A meticulous search of the literature did not result in the finding of any report of Kaposi’s sarcoma associated with a paraneoplastic picture from the nervous system, nor with any related to direct peripheral nerve invasion by this particular malignancy. However, this possibility cannot be excluded in our patient, and in view of our inability to find another cause responsible for his symptoms, if we wanted to put everything under one basic pathogenetic process, it would be very tempting to attribute the whole picture to the underlying malignancy.

On the other hand, it would be very difficult to accept that Kaposi’s sarcoma in our patient developed iatrogenically, following immunosuppression. Kaposi’s sarcoma may be caused by iatrogenic immunosuppression, but this has been mainly reported in transplant patients, receiving heavy immunosuppressive treatment with cyclosporin A and steroids with azathioprine. In addition, our patient must have Kaposi’s lesions, although not diagnosed, as it could be documented from the presentation, before methotrexate was started.

In conclusion, although peripheral and cranial nerve involvement has not been reported in Kaposi’s sarcoma, we postulate that the patient’s condition could be attributed to this within the context of a paraneoplastic process.

A 72-year-old man with ipsilateral headache, skin lesions and neuropathy.

Facial nerve pulsy and peripheral neuropathy.

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) or other systemic vasculitis vs paraneoplastic manifestations in the context of Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Raised inflammatory markers and anemia.

Negative computed tomography (CT) scan of thorax-abdomen, negative brain CT and magnetic resonance imaging.

Biopsies of skin lesions diagnostic of Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Initial treatment with high-dose steroids with the diagnosis of GCA. Following diagnosis of Kaposi’s sarcoma, the patient was successfully treated with interferon.

A paraneoplastic process may present with atypical manifestations.

Although peripheral and cranial nerve involvement has not been reported in Kaposi’s sarcoma, authors postulate that the patient’s picture could be attributed to this within the context of a paraneoplastic process. This is a very interesting case.

P- Reviewers: Campbell JH, Juan DS S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Ma JY E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Niederkohr RD, Levin LA. A Bayesian analysis of the true sensitivity of a temporal artery biopsy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:675-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Caselli RJ, Daube JR, Hunder GG, Whisnant JP. Peripheral neuropathic syndromes in giant cell (temporal) arteritis. Neurology. 1988;38:685-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zamarbide ID, Maxit MJ. Fisher’s one and half syndrome with facial palsy as clinical presentation of giant cell temporal arteritis. Medicina (B Aires). 2000;60:245-248. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Eggenberger E. Eight-and-a-half syndrome: one-and-a-half syndrome plus cranial nerve VII palsy. J Neuroophthalmol. 1998;18:114-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Taillan B, Fuzibet JG, Vinti H, Castela J, Gratecos N, Dujardin P, Pesce A. Peripheral facial paralysis disclosing Horton’s disease. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. 1989;56:342. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Bakchine S, Côte D, Massiou H, Derouesné C. A case of peripheral facial paralysis in Horton’s disease. Presse Med. 1985;14:2062. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Roomet A, Allen JS. Temporal arteritis heralded by facial nerve palsy. JAMA. 1974;228:870-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Asakura K, Muto T. Neurological involvement in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Brain Nerve. 2013;65:1311-1317. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Colmegna I, Maldonado-Cocco JA. Polyarteritis nodosa revisited. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2005;7:288-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vaglio A, Buzio C, Zwerina J. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss): state of the art. Allergy. 2013;68:261-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hammad TA, Hajj-Ali RA. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system and reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15:346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |