Published online Apr 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i4.104

Revised: December 27, 2013

Accepted: February 18, 2014

Published online: April 16, 2014

Processing time: 170 Days and 2.6 Hours

A case of osteoid osteoma of the elbow in a patient with hemophilia A is described. This male patient presented with chronic and nocturnal pain of the left elbow which was alleviated with acetaminophen. Besides pain, he also complained of stiffness. Before these complaints, he had recurrent bleedings in the elbow because of hemophilia. A delayed diagnosis of osteoid osteoma in the proximal part of the left ulna was established by a bone scan and a multislice spiral computed tomography (CT) scan. The lesion was surgically removed under CT-guidance. The histopathological analyses did not show specific features of osteoid osteoma. Two months after the operation, the complaints decreased and the range of motion of the left elbow improved. A diagnosis of osteoid osteoma of the elbow should be considered in young adult patients with persistent elbow pain and histological confirmation is not always necessary.

Core tip: Two issues are emphasized by reporting this case. Firstly, it is important to recognize the possibility of osteoid osteoma in a young adult patient with persistent chronic and nocturnal elbow pain which is alleviated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Secondly, histopathological confirmation is not always possible and necessary to establish the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma.

- Citation: Bekerom MPJVD, Hooft MAAV, Eygendaal D. Osteoid osteoma of the elbow mimicking hemophilic arthropathy. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(4): 104-107

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i4/104.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i4.104

Osteoid osteoma is a benign tumor in young adults and is relatively common, accounting for approximately 10%-12% of all benign skeletal neoplasms[1-3]. Jaffe[4] first described this entity in 1935 as a distinct osteoblastic skeletal tumor. It usually occurs in the second and third decade of life and the male/female sex ratio is approximately 3:1[1,3]. This tumor is curable by surgical excision. About 50% to 60% of osteoid osteomas occur in the long bones of the lower extremities and the femoral neck is the single most frequent anatomic site. In these cases, the diagnosis is usually typical. However, in the upper extremities where the bones of the elbow are the most frequent anatomic site, the clinical and imaging picture may be misleading, often mimicking other entities. This poses a challenge to the diagnosis which is often delayed, resulting in a significantly negative impact on the patient’s quality of life[3,5]. Making the diagnosis is especially difficult when the patient is known to have other joint pathology. We describe a case of osteoid osteoma mimicking arthropathy of the elbow in a patient with hemophilia.

A 29-year-old man presented with chronic pain of the left elbow that was alleviated with painkillers. The pain had started suddenly 1.5 years ago after lifting a weight. The patient had locking complaints, nocturnal pain and pain at rest. He also had hemophilia A with recurrent bleedings in the elbow and progressive extension deficit of the elbow. A previous arthroscopy was performed but without improving the range of motion and diminishing pain. Physical examination of the left elbow revealed mild crepitus and no hydrops of the joint. Flexion of the elbow was possible until 110 degrees and there was an extension deficiency of 30 degrees. Pronation and supination was possible until 60 and 80 degrees respectively. Palpation of the lateral epicondyle and the proximal ulna was painful. There were no neurological or vascular abnormalities.

A plain radiograph (Figure 1) and a computed tomography (CT) scan performed in April 2007 revealed only osteoarthrotic changes without visualization of a nidus. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed a synovitis and hydrops and therefore a synovectomy was performed, without improvement in motion and pain.

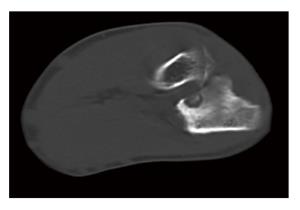

A bone scan showed a circumscript hyperemic and metabolic active focus in the proximal part of the left ulna. These findings match the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma, cartilage lesion, osteomyelitis and a fissure or fracture. In December 2007, a multislice spiral CT scan showed early degenerative changes of the left elbow joint with signs of arthritis. It also confirmed the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma in the proximal ulna with a clearly calcified central nidus just distal from the proximal radioulnar joint and with surrounding periost reaction. The measurement of the lesion was 12 mm × 8 mm.

The patient was given clotting factor VIII preoperatively and a CT-guided surgical excision of the lesion was performed (Figure 2). The histological analyses showed cancellous bone with sclerotic changes without specific features. A second opinion was sought from the national committee on bone tumors at Leiden University medical center and by consensus they confirmed the diagnosis osteoid osteoma, although histological analyses did not establish it.

Two months after the operation, the pain had decreased and the function of the elbow had improved. Flexion was possible until 120 degrees and there was an extension deficiency of 20 degrees. A plain radiograph of the left elbow performed after the operation showed a decrease of sclerotic changes in the proximal ulna. One year after surgical excision of the lesion the patient was discharged from follow up.

The general clinical presentation is the persistence of a dull, diffuse, aching pain of increasing severity. The pain is frequently worse at night and is alleviated by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents[1,3,5]. Because clinical features precede imaging, there is frequently a delay in the diagnosis and patients are often treated for and suspected of having other conditions. Osteoid osteoma of the elbow may masquerade as a non-specific synovitis. However, the possibility of osteoid osteoma must be considered in the presence of persistent pain with diminished range of movement of unknown etiology[2,5].

Osteoid osteoma is a benign tumor that consists of a well-demarcated osteoblastic mass called a nidus that is surrounded by a distinct zone of reactive bone sclerosis. The zone of sclerosis is not an integral part of the tumor and represents a secondary reversible change that gradually disappears after the removal of the nidus. The nidus tissue has a limited local growth potential and usually is less than 1 cm in diameter[3]. The elbow is a rare location in which to find osteoid osteoma. Bruguera et al[6] identified only four osteoid osteomas among all primary tumors of the elbow in the Leeds Regional Bone Tumour Registry.

Our patient had a history of hemophilia A. This is an X-linked inherited bleeding disorder characterized by a deficiency of clotting factor VIII[7,8]. Arthropathy caused by recurrent intra-articular hemorrhages is a common complication of severe hemophilia. The elbow joint is the second most common site of arthropathy in the hemophilic patient. Severe arthropathy of the elbow is complicated by pain, stiffness, reduced range of motion and chronic synovitis[9,10]. This comorbidity complicated and delayed the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma in the described case.

The radiological features of osteoid osteoma of the elbow include the following triad: (1) osteosclerosis, usually a dominant feature at initial imaging and typically enveloping the nidus; (2) joint effusion; and (3) a periostal reaction that can involve both the bone in which the osteoid osteoma arises and adjacent bones. Awareness of these features will facilitate making the correct diagnosis, thereby facilitating timely and appropriate treatment[2]. About a quarter of osteoid osteomas are not detected on plain radiographs. CT scan, bone scintigraphy and MRI are useful to make an early and correct diagnosis. Although MRI is not very helpful in diagnosing osteoid osteoma, it can be beneficial in showing the inflammatory reaction produced by osteoid osteoma and in excluding other associated pathologies[1,3,11].

In the described case the nidus was not observed on plain radiographs. Because of persisting complaints and clinical symptoms with normal radiographic examination, a bone scintigram was performed which showed an increased uptake of radioisotope. Additionally, a multi-slice CT scan was performed which localized the nidus, accurately disclosing its relationship with the surrounding anatomical structures, thus beneficial for the pre-operative planning[5].

The histology of osteoid osteoma in the elbow is indistinguishable from that in typical locations[2]. The lesion is usually smaller than 1.5 cm in diameter and is composed of a central core of vascular osteoid tissue (nidus) surrounded by a peripheral zone of reactive sclerotic bone. The nidus appears as a distinct oval or round reddish area that can be easily separated from its bed. Microscopically, the nidus consists of thin bone trabeculae uniformly distributed in loose stromal vascular connective tissue. The trabeculae are usually thin and their size varies from lesion to lesion and in different areas of the same nidus. The central portion of the nidus is heavily ossified and less cellular compared with the more cellular but less mineralized peripheral portion[3,5].

The diagnosis of osteoid osteoma in the described case was based on history, physical examination and radiology and was not confirmed by the pathology examination but by consensus of the national bone tumor committee. The complaints decreased and the range of motion improved after surgical excision of the tumor. In nearly 20% of patients surgical exploration fails to uncover the nidus, according to the Mayo clinic data[3]. Persistence of typical symptoms after surgery may mean that the nidus was not (completely) removed and that only surrounding reactive bone was excised. Some patients obtained complete postoperative relief of symptoms without histopathological confirmation of an osteoid osteoma nidus. This was possibly because the nidus may have been so small in relationship to the abundant surrounding sclerotic bone that it was removed but not recognized by the surgeon and thus not delivered for pathological examination; or the nidus may have been present in the specimens but was missed on histological survey; or the nidus may not have been found on pathological examination because of damage to the friable tissue or separation of the nidus[12].

A conservative treatment for osteoid osteoma described in the literature is management with anti-inflammatory drugs for 30 to 40 mo which can induce permanent relief of symptoms and regression of the nidus observed on radiographs[13]. However, given the tendency for synovitis and loss of motion with a prolonged period of symptoms from osteoid osteoma of the elbow, the indicated treatment is total excision of the nidus, either by open surgery or by radio-frequency percutaneous ablation[3,5,11].

Two issues were emphasized by reporting this case. Firstly, it is important to recognize the possibility of osteoid osteoma in a young adult patient with persistent chronic and nocturnal pain in the elbow which is alleviated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Secondly, histopathological confirmation is not always possible and necessary to establish the diagnosis osteoid osteoma.

There are no financial or non-financial (political, personal, religious, ideological, academic, intellectual, commercial or any other) competing interests of the authors or a member of their immediate families to declare in relation to this manuscript. This case was also described in Dutch in the national orthopedic (non-indexed) journal.

A case of osteoid osteoma of the elbow in a patient with hemophilia A is described. This male patient presented with chronic and nocturnal pain of the left elbow which was alleviated with acetaminophen. Besides pain, he also complained of stiffness. Before these complaints he had recurrent bleedings in the elbow because of hemophilia.

Physical examination of the left elbow revealed mild crepitus and no hydrops of the joint. Flexion of the elbow was possible until 110 degrees and there was an extension deficiency of 30 degrees. Pronation and supination was possible until 60 and 80 degrees respectively.

The possibility of osteoid osteoma must be considered in the presence of persistent pain with diminished range of movement of unknown etiology.

A delayed diagnosis of osteoid osteoma in the proximal part of the left ulna was established by a bone scan and a multislice spiral computed tomography (CT) scan.

The lesion was surgically removed under CT-guidance. The histopathological analyses did not show specific features of osteoid osteoma.

Firstly, it is important to recognize the possibility of osteoid osteoma in a young adult patient with persistent chronic and nocturnal pain in the elbow which is alleviated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Secondly, histopathological confirmation is not always possible and necessary to establish the diagnosis osteoid osteoma.

This manuscript illustrates a unique case of osteoid osteoma of the elbow in a patient with hemophilia. The article is well-written and does not require modifications.

P- Reviewers: Fette AM, Hirose H, Matuszewski L, Mazzocchi M, Mazzocchi M, Ortmaier R S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Franceschi F, Marinozzi A, Papalia R, Longo UG, Gualdi G, Denaro E. Intra- and juxta-articular osteoid osteoma: a diagnostic challenge : misdiagnosis and successful treatment: a report of four cases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2006;126:660-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Moser RP, Kransdorf MJ, Brower AC, Hudson T, Aoki J, Berrey BH, Sweet DE. Osteoid osteoma of the elbow. A review of six cases. Skeletal Radiol. 1990;19:181-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dorfman HD, Czerniak B. Benign osteoblastic Tumors. Bone Tumors, 3rd ed. St Louis: Mosby 1998; 85-127. |

| 4. | Jaffe HL. Osteoid-osteoma. Proc R Soc Med. 1953;46:1007-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Themistocleous GS, Chloros GD, Benetos IS, Efstathopoulos DG, Gerostathopoulos NE, Soucacos PN. Osteoid osteoma of the upper extremity. A diagnostic challenge. Chir Main. 2006;25:69-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bruguera JA, Newman RJ. Primary tumors of the elbow: a review of the Leeds Regional Bone Tumour Registry. Orthopedics. 1998;21:551-553. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Luck JV, Silva M, Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Ghalambor N, Zahiri CA, Finn RS. Hemophilic arthropathy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12:234-245. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Heyworth BE, Su EP, Figgie MP, Acharya SS, Sculco TP. Orthopedic management of hemophilia. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2005;34:479-486. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Malhotra R, Gulati MS, Bhan S. Elbow arthropathy in hemophilia. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121:152-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Utukuri MM, Goddard NJ. Haemophilic arthropathy of the elbow. Haemophilia. 2005;11:565-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Weber KL, Morrey BF. Osteoid osteoma of the elbow: a diagnostic challenge. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1111-1119. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Sim FH, Dahlin CD, Beabout JW. Osteoid-osteoma: diagnostic problems. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:154-159. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kneisl JS, Simon MA. Medical management compared with operative treatment for osteoid-osteoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:179-185. [PubMed] |