Published online Oct 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i29.109406

Revised: June 24, 2025

Accepted: August 8, 2025

Published online: October 16, 2025

Processing time: 110 Days and 21.2 Hours

Intestinal obstruction (IO) in pregnancy, though rare (1:1500-1:66000), carries high maternal (6%-10%) and fetal mortality (26%). Adhesions from prior surgery are the leading cause. Diagnosis is often delayed due to symptom overlap with nor

A 25-year-old gravida 2 para 1 woman at 28 weeks of gestation presented with 1-week constipation, feculent vomiting, and abdominal distension. She had a history of exploratory laparotomy in 2015 for blunt abdominal trauma. The diagnosis of IO in pregnancy was confirmed via abdominopelvic ultrasound and clinical findings. Interventions included conservative measures (nasogastric tube decompression, enemas) followed by emergency laparotomy with bowel resec

High clinical suspicion, expedited cross-sectional imaging (computed tomogra

Core Tip: Intestinal obstruction in pregnancy, though rare, carries catastrophic risks - including a 20%-30% maternal mortality rate when complicated by perforation. We present a tragic case of small bowel obstruction in a 25-year-old woman at 28 weeks of gestation, leading to perforation, sepsis, fetal loss, and maternal death. This case underscores three critical lessons: (1) Abdominal pain in pregnancy with a surgical history demands immediate imaging (low-dose computed tomography/Magnetic resonance imaging if ultrasound equivocal); (2) Multidisciplinary teams must collaborate for time-sensitive interventions; and (3) Delayed surgery beyond 24 hours of symptoms increases mortality risk.

- Citation: Omullo FP, Anyango OS, Mutua BM, Odoyo MO, Gogo HM, Obung'a VO. Fatal small bowel perforation complicating intestinal obstruction in pregnancy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(29): 109406

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i29/109406.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i29.109406

Intestinal obstruction (IO) complicates 0.001%-0.003% of pregnancies, with adhesions (60%) and volvulus (25%) as leading causes[1]. The gravid uterus exacerbates obstruction via mechanical compression of the bowel, particularly in the second and third trimesters. Maternal mortality reaches 10% with perforation; fetal loss exceeds 20%[2]. Diagnosis is challenging due to nonspecific symptoms (nausea, bloating) and reluctance to use radiation-based imaging[3]. We report a fatal case of adhesive intestinal obstruction during pregnancy, underscoring diagnostic challenges and consequences of delayed intervention.

A 25-year-old gravida 2 para 1, casual laborer, at 28 weeks of gestation, presented with 1-week constipation, feculent vomiting, and progressive abdominal distension.

The patient, gravida 2, para 1, had been experiencing abdominal discomfort for one week, which progressively worsened. She reported a bloated abdomen, inability to pass stool or gas, and intermittent vomiting. Her vomiting, initially non-bilious, became feculent and occurred more frequently postprandially. There was no history of trauma or recent surgery since her previous laparotomy in 2015 for blunt abdominal injury following a road traffic accident.

Obstetric and gynaecological history: The patient had a history of irregular menstrual cycles, with her last menstrual period unknown and an estimated date of delivery in June 2025. She had used Depo-Provera as contraception and re

The patient had undergone an exploratory laparotomy in 2015 due to abdominal injury, with no complications reported afterwards. She had no history of diabetes, hypertension, or other chronic illnesses.

The patient’s mother had a history of hypertension. The patient was a single, casual laborer with no significant family history of gastrointestinal disorders.

The patient appeared cachectic and mildly dehydrated. Vital signs were as follows: Blood pressure 117/90 mmHg, pulse 117 beats per minute, respiratory rate 22 breaths per minute, and afebrile. On abdominal examination, the abdomen was distended, and there was visible peristalsis and diffuse tenderness on palpation. Other systemic examinations were unremarkable.

Laboratory examinations are included in Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4.

| Parameter | Results | Result units | Reference range |

| WBC | 3.79 | × 109/L | 4.0–10.0 × 109 |

| Neutrophils | 81.6 | % | 40–75 |

| Lymphocytes | 11.1 | % | 21–40 |

| Monocytes | 5.4 | % | 3–12 |

| Eosinophils | 1.4 | % | 0.5–5 |

| Basophils | 0.5 | % | 0.5–5 |

| Neutrophils absolute | 3.1 | × 109/L | 1.8–6.3 |

| Lymphocytes absolute | 0.42 | × 109/L | 1.1–3.2 |

| Monocytes absolute | 0.21 | × 109/L | 0.1–0.6 |

| Eosinophils absolute | 0.05 | × 109/L | 0.02–0.52. |

| Basophils absolute | 0.01 | × 109/L | 0.0–6.3 |

| RBC | 4.48 | × 109/L | 4.7–6.1 |

| HB | 12.5 | g/dL | 11.2–16.0 |

| HCT | 37.5 | % | 37.0–47.0 |

| MCV | 83.8 | fL | 76.0–100.0 |

| MCH | 33.4 | pg | 27.0–31.0 |

| MCHC | 46.2 | g/dL | 32.0–36.0 |

| RDW-CV | 13.1 | % | 35.0–56.0 |

| Platelets | 241 | × 109/L | 160.0–450.0 |

| MPV | 9.5 | fL | 6.5–12.0 |

| PDW | 15.9 | % | 9.0–17.0 |

| PCT | 0.228 | % | 0.108–0.282 |

| Parameter | Results | Result units | Reference range |

| Albumin | 18.33 | g/L | 35–52 |

| ALP | 0 | U/L | 35–104 |

| ALT | 46.2 | U/L | 0–40 |

| AST | 23.9 | U/L | 0–32 |

| GGT | 6.7 | U/L | 5–36 |

| Total protein | 33.4 | g/L | 66-87 |

| Parameter | Results | Result units | Reference range |

| Chloride | 101.5 | mmol/L | 95–107 |

| Creatinine | 66 | μmol/L | 44–80 |

| Potassium | 2.86 | mmol/L | 3.5–5.1 |

| Sodium | 134.7 | mmol/L | 135-145 |

| Urea | 4.94 | mmol/L | 2.76-8.07 |

| Parameter | Results | Result units | Reference range |

| CRP | 205.2 | mg/L | 0–10.0 |

An abdominopelvic ultrasound demonstrated dilated loops of small bowel, suggesting bowel obstruction and a single viable intrauterine pregnancy in cephalic presentation at 26 weeks 4 days. The patient was prepared for emergency intervention.

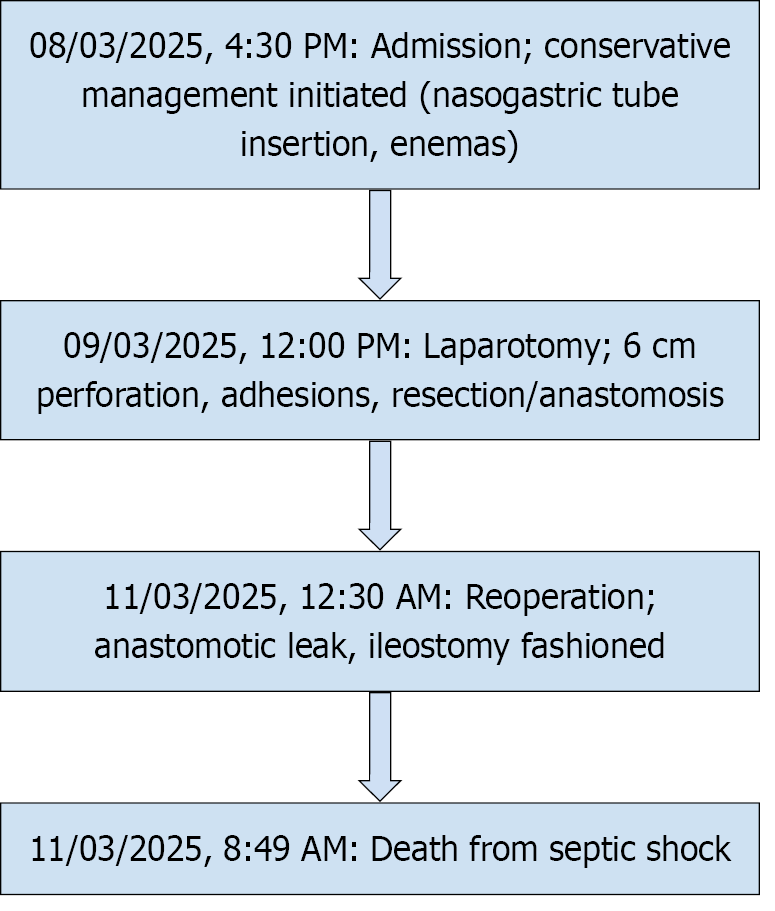

The flow diagram summarizing the timeline of clinical events is included in Figure 1.

Given the patient's deteriorating clinical status and worsening abdominal distension, the surgical team was consulted, and an emergency exploratory laparotomy was planned. The patient was started on ‘nil per os’ status, and intravenous fluids were administered. A nasogastric tube was inserted under light sedation. Despite an initial slight improvement after the enema, the patient's condition worsened with continued bloating and visible peristalsis. The surgery was decided after consultations with obstetrics, anesthesiology, and the surgical team.

The patient was diagnosed with intestinal obstruction, secondary to adhesions from a previous laparotomy.

The patient underwent emergency exploratory laparotomy, which revealed a substantial perforation (6.0 cm by 3.0 cm) on the anti-mesenteric border of the ileum, located 30 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve. The affected segment exhibited signs of transmural necrosis with surrounding fibrinous exudate. A segmental resection encompassing 10 cm of non-viable small bowel, followed by end-to-end anastomosis, was performed. Further exploration revealed dense fibrous adhesions forming a stricture and loop 20 cm from the perforated site. A peritoneal lavage was carried out using warm saline, and the abdomen was closed in layers. Tissue was sent for histopathology. Postoperatively, the patient was managed with intravenous antibiotics (ceftriaxone and metronidazole), analgesics, supportive care, and isotonic fluids.

Following the initial exploratory laparotomy, the patient was admitted to the ward for close monitoring. Despite supportive care with intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and analgesia, her clinical condition remained guarded. 2 days post-admission, the patient had a spontaneous miscarriage, confirmed after the expulsion of fetal tissue. She was managed with rectal misoprostol administration to aid complete evacuation.

Post-miscarriage, the patient became increasingly tachycardic, tachypneic, and hypoxic, requiring escalation of oxygen therapy. Surgical review and abdominopelvic imaging indicated persistent intra-abdominal pathology. She underwent a second emergency exploratory laparotomy, which revealed foul-smelling intestinal leakage and a perforation near the previous anastomosis site. A resection with ileostomy formation was performed, and multiple drains were inserted.

Postoperatively, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for critical care support. Despite aggressive management, including broad-spectrum antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, and ventilation support, the patient developed worsening sepsis. Day 3 post-admission, she suffered a cardiac arrest and, despite resuscitative efforts, there was no return of spontaneous circulation. She was pronounced dead at 8:49 AM.

IO during pregnancy is a rare but critical condition[1]. Adhesions are the most common cause, followed by volvulus, hernias, and malignancies[2]. Our patient’s prior laparotomy (2015) for trauma significantly elevated her risk of obstruc

Clinically, IO often mimics benign pregnancy symptoms (nausea, constipation), leading to delayed diagnosis in 40%-60% of cases[3]. In our patient, progressive abdominal distension and feculent vomiting were red flags. Delayed recognition increases the risk of bowel ischemia (30%-40%), perforation (10%-15%, and sepsis, with maternal mortality escalating to 20%-30% if surgery occurs after 48 hours post-perforation[1,2].

Diagnostic challenges persist due to fetal safety concerns. Despite being the first-line, ultrasound’s sensitivity for IO remains limited[3,5]. While magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) avoids radiation, its underutilization in low-resource settings often delays diagnosis. However, low-dose computed tomography (CT) may be employed when clinical suspicion is high[6]. Our patient’s abdominopelvic ultrasound revealed dilated loops but missed the perforation, underscoring the pitfalls of relying on ultrasound alone[7].

Management hinges on gestational age and obstruction severity. Conservative measures may suffice for partial obstructions[8], but complete obstructions require surgery within 24 hours to reduce maternal mortality. Delayed intervention (> 72 hours from symptom onset) likely contributed to transmural necrosis and perforation, consistent with recent data showing leak rates of 15%-20% in emergency bowel resection during pregnancy[2].

The spontaneous miscarriage (28 weeks) aligns with studies reporting fetal loss rates of 25%-40% in IO complicated by perforation[9]. Surgical stress and sepsis trigger pro-inflammatory cytokine release, exacerbating uterine irritability[10]. Close fetal monitoring is imperative, yet even with optimal care, preterm delivery occurs in 45%-60% of cases requiring laparotomy[11]. Postoperative sepsis has a high mortality rate in pregnancy due to immunological adaptation[12]. Sepsis was managed per Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines[13], though vasopressor access and mechanical ventilation were delayed due to ICU bed shortages. Recent benchmarks emphasize goal-directed resuscitation (late monitoring, early vasopressors) and broad-spectrum antibiotics (carbapenems)[14].

Recent studies have reported similar cases (Table 5). Outcomes vary depending on time to diagnosis, surgery promptness, and postoperative care quality[15-18]. Delayed intervention consistently results in poorer maternal and fetal outcomes. This case highlights the significance of high clinical suspicion for early diagnosis and multidisciplinary management in managing IO in pregnancy.

| Ref. | Key findings | Management | Outcome |

| Shen et al[15], 2023 | IO at 34 weeks of gestation presenting as uterine perforation | Initial conservative treatment failed. Emergency cesarean section followed by surgical repair of uterine rupture | Maternal recovery; fetal outcome not specified |

| Zhao et al[16], 2020 | IO due to reverse rotation of the midgut at 26 weeks of gestation; rare anatomical cause | Surgical correction via laparotomy | Both mother and fetus had favorable outcomes |

| Daimon et al[17], 2016 | IO at 20 weeks of gestation due to adhesions | Laparotomy after failure of conservative treatment | Both mother and fetus recovered well |

| Loukopoulos et al[18], 2022 | IO at 30 weeks gestation presenting with atypical symptoms; initial misdiagnosis | Laparotomy after correct diagnosis | Successful outcomes for both mother and fetus |

| Current case | G2P1 woman at 28 weeks with IO due to adhesions post-laparotomy; delayed presentation. Initial ultrasound | Laparotomy after > 72 hours; found perforation and contamination. Spontaneous miscarriage, anastomotic leak | Fetal and maternal mortality |

Inconclusive ultrasounds warrant low-dose CT or MRI, as endorsed by the ACR Appropriateness Criteria®. National guidelines must incorporate such flexibility to allow clinicians discretion in life-threatening emergencies. Resource-constrained settings may benefit from task-sharing radiologist training or telemedicine collaborations to improve access[19].

Postoperative deterioration in this case was likely exacerbated by limited ICU support, which is a common constraint in many low-resource settings. Investment in critical care infrastructure is vital to improving survival in such emer

This case highlights the need for guidelines promoting early CT/MRI in pregnant women with suspected IO, particularly in resource-limited settings. Multidisciplinary protocols must prioritize timely surgical intervention to mitigate cata

The authors gratefully acknowledge the clinical staff at Makueni County Referral Hospital for their dedicated patient care and the patient’s family for sharing this case for educational purposes.

| 1. | Kalu E, Sherriff E, Alsibai MA, Haidar M. Gestational intestinal obstruction: a case report and review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2006;274:60-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Webster PJ, Bailey MA, Wilson J, Burke DA. Small bowel obstruction in pregnancy is a complex surgical problem with a high risk of fetal loss. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2015;97:339-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zachariah SK, Fenn M, Jacob K, Arthungal SA, Zachariah SA. Management of acute abdomen in pregnancy: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2019;11:119-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fatehi Hassanabad A, Zarzycki AN, Jeon K, Deniset JF, Fedak PWM. Post-Operative Adhesions: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanisms. Biomedicines. 2021;9:867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Woodfield CA, Lazarus E, Chen KC, Mayo-Smith WW. Abdominal pain in pregnancy: diagnoses and imaging unique to pregnancy--review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:WS14-WS30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Masselli G, Bonito G, Gigli S, Ricci P. Imaging of Acute Abdominopelvic Pain in Pregnancy and Puerperium-Part II: Non-Obstetric Complications. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:2909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Coppolino F, Gatta G, Di Grezia G, Reginelli A, Iacobellis F, Vallone G, Giganti M, Genovese E. Gastrointestinal perforation: ultrasonographic diagnosis. Crit Ultrasound J. 2013;5 Suppl 1:S4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ling XS, Anthony Brian Tian WC, Augustin G, Catena F. Can small bowel obstruction during pregnancy be treated with conservative management? A review. World J Emerg Surg. 2024;19:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chuang MT, Chen TS. Bowel obstruction and perforation during pregnancy: Case report and literature review. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;60:927-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Clements TW, Tolonen M, Ball CG, Kirkpatrick AW. Secondary Peritonitis and Intra-Abdominal Sepsis: An Increasingly Global Disease in Search of Better Systemic Therapies. Scand J Surg. 2021;110:139-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | George PE, Shwaartz C, Divino CM. Laparoscopic surgery in pregnancy. WJOG. 2016;5:175. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Budianu MA, Crişan AI, Voidăzan S. Maternal sepsis - challenges in diagnosis and management: A mini-summary of the literature. Acta Marisiensis - Seria Medica. 2024;70:3-7. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, Machado FR, Mcintyre L, Ostermann M, Prescott HC, Schorr C, Simpson S, Wiersinga WJ, Alshamsi F, Angus DC, Arabi Y, Azevedo L, Beale R, Beilman G, Belley-Cote E, Burry L, Cecconi M, Centofanti J, Coz Yataco A, De Waele J, Dellinger RP, Doi K, Du B, Estenssoro E, Ferrer R, Gomersall C, Hodgson C, Møller MH, Iwashyna T, Jacob S, Kleinpell R, Klompas M, Koh Y, Kumar A, Kwizera A, Lobo S, Masur H, McGloughlin S, Mehta S, Mehta Y, Mer M, Nunnally M, Oczkowski S, Osborn T, Papathanassoglou E, Perner A, Puskarich M, Roberts J, Schweickert W, Seckel M, Sevransky J, Sprung CL, Welte T, Zimmerman J, Levy M. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:1181-1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 2285] [Article Influence: 571.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Joseph J, Sinha A, Paech M, Walters BN. Sepsis in pregnancy and early goal-directed therapy. Obstet Med. 2009;2:93-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shen J, Teng X, Chen J, Jin L, Wang L. Intestinal obstruction in pregnancy-a rare presentation of uterine perforation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23:507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhao XY, Wang X, Li CQ, Zhang Q, He AQ, Liu G. Intestinal obstruction in pregnancy with reverse rotation of the midgut: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:3553-3559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Daimon A, Terai Y, Nagayasu Y, Okamoto A, Sano T, Suzuki Y, Kanki K, Fujita D, Ohmichi M. A Case of Intestinal Obstruction in Pregnancy Diagnosed by MRI and Treated by Intravenous Hyperalimentation. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2016;2016:8704035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Loukopoulos T, Zikopoulos A, Galani A, Skentou C, Kolibianakis E. Acute intestinal obstruction in pregnancy after previous gastric bypass: A case report. Case Rep Womens Health. 2022;36:e00473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Francisco MZ, Altmayer S, Carlesso L, Zanon M, Eymael T, Lima JE, Watte G, Hochhegger B. Appropriateness and imaging outcomes of ultrasound, CT, and MR in the emergency department: a retrospective analysis from an urban academic center. Emerg Radiol. 2024;31:367-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |