Published online Oct 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i29.109027

Revised: June 5, 2025

Accepted: August 1, 2025

Published online: October 16, 2025

Processing time: 122 Days and 7.7 Hours

An epidural abscess is a rare but serious medical condition where a pocket of pus forms in the epidural space — the area between the outer covering of the spinal cord (the dura mater) and the bones of the spine. It’s usually caused by a bacterial infection, most commonly Staphylococcus aureus. The infection can spread to this area from other parts of the body, through the bloodstream, or it may be intro

Spinal epidural abscess (SEA) represents a rare yet potentially severe infection affecting the epidural space. We present the following case of a 54-year-old Hispanic white male who initially presented to the emergency department with acute deteriorating symptoms of bilateral lower extremity weakness, which subsequently progressed to involve the upper extremities. However, further evaluation uncovered additional notable symptoms, including urinary inconti

This case highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for SEA in patients presenting with atypical symptoms, even in the setting of seemingly unrelated conditions. Early recognition and prompt intervention are crucial to prevent permanent neurological deficits and improve outcomes in patients with SEA.

Core Tip: This case report presents an unusual clinical scenario describing a 54-year-old male who was admitted after acute deteriorating symptoms of bilateral lower extremity weakness, which subsequently progressed to involve the upper extremities. Unexpectedly, neuroimaging, magnetic resonance imaging of the spine, confirmed the presence of C5-C6 osteomyelitis and a C6-C7 spinal epidural abscess with severe canal narrowing. This imaging finding was remarkable given the significant neurological deficits. Surgical intervention started with long term antibiotics that improved the patient’s symptoms. Other info: (1) Informed consent was obtained; (2) Does not apply to case reports; (3) Manuscript has been reviewed multiple times; and (4) Spinal epidural abscess. The case has an educational value regarding rare occurrence of spinal epidural abscess after a urinary tract infection.

- Citation: AlSabea N, Kanor U, Garcia AS, Shah A, Sun A. Spinal epidural abscess of uncommon presentation following urinary tract infection: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(29): 109027

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i29/109027.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i29.109027

Spinal epidural abscess (SEA) is a rare but serious condition characterized by the accumulation of purulent material located between the dura mater and the vertebral wall. Although SEA comprises only a small percentage of spinal infections, it poses significant risks, including irreversible neurological deficits and potential mortality if not promptly identified and treated. The incidence of SEA is estimated to range from 2.0 to 20 cases per 10000 hospital admissions, with reports of a two- to six-fold increase in recent decades[1]. Early diagnosis and intervention are crucial, as historical outcomes were often fatal before the advent of advanced imaging and surgical techniques A 2018 review of 1094 patients with SEAs reported adjusted mortality rates of 3.7%-5%. However, more than one-third of SEA survivors have poor neurological outcomes[2].

SEA commonly arises from hematogenous spread of infection, direct extension from adjacent infections, or post-surgical complications. Risk factors include chronic organ dysfunction (e.g., end-stage renal disease, liver disease), intravenous drug use, and invasive spinal procedures. Other factors like alcoholism, human immunodeficiency virus infection, morbid obesity, long-term corticosteroid use, pregnancy, and trauma also contribute. Notably, diabetes mellitus presents a high risk, particularly in patients who do not engage in high-risk behaviors, affecting approximately 21%-42.9% of reported cases[3,4]. Clinically, patients may present with the classic triad of (1) Pyrexia; (2) Neck or back pain; and (3) Neurological deficit. However, a high index of suspicion for SEA is necessary as only 8%-15% of patients present with this triad[5]. Delays in diagnosis are common, occurring in up to 89% of cases[5]. Patients are often examined by multiple physicians prior to a diagnosis, underscoring the importance of timely intervention to prevent irreversible damage.

Staphylococcal aureus remains the most prevalent causative organism in SEA, accounting for approximately 60%-90% of cases. Both methicillin-sensitive (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant (MRSA) strains are implicated, with MRSA infections associated with more severe clinical outcomes. The primary route of infection is hematogenous dissemination, often originating from distant sites such as skin, respiratory tract, or urinary tract[6]. The valveless venous network of Batson’s plexus may facilitate spread of pathogens to the epidural space, particularly from the pelvic region[7].

Beyond S. aureus, a diverse array of pathogens can lead to SEA. Gram-negative bacilli, notably Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, are recognized cases, especially in patients with urinary tract infections or those who use intravenous drugs[8]. Streptococcal species, including Streptococcus agalactiae, have also been documented as known sources. Anaerobic bacteria such as Bacteroides species, as well as fungi like Candida and Aspergillus, are rare but noteworthy pathogens, particularly in immunocompromised individuals or following invasive spinal procedures[9]. Additionally, Mycobacterium tuberculosis should be considered in endemic regions or among immunosuppressed populations, as it can lead to chronic epidural infections[10].

Management typically involves both surgical decompression and targeted antibiotic therapy. The timing and choice of these interventions depend on several risk factors, including the severity of the neurological deficit, the patient’s overall health, and the characteristics of the abscess itself. Understanding the broad spectrum of potential pathogens is crucial for initiating appropriate empirical antimicrobial therapy and for tailoring treatment based on culture results. Prompt surgical intervention is often necessary to alleviate pressure on the spinal cord.

This case report details the diagnostic challenges and treatment strategies in an atypical presentation of SEA, aiming to enhance understanding and guide clinical practice in managing this complex condition. This report seeks to contribute to the literature by providing insights into effective management strategies, emphasizing the need for a high index of suspicion, and underscoring the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in achieving successful outcomes. Through this case, we hope to guide clinicians in recognizing atypical presentations and making informed decisions to optimize patient care.

A 54 year-old male with a past medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted to the hospital for evaluation of progressively worsening neck pain for two weeks and associated with generalized weakness in upper and lower extremities and urinary incontinence with dysuria.

The patient, a 54-year-old male with a past medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, presented to the emergency department with initial symptoms of urinary incontinence and dysuria, which suddenly developed into acute onset bilateral lower extremity weakness which began three weeks prior and rapidly progressed to involve the upper extremities. Previously ambulatory, he experienced a rapid functional decline over the preceding two days, ultimately losing the ability to take any steps. He also reported back pain, loss of bowel and bladder function, and worsening chronic neck pain with a one year history of torticollis. The patient denied any history of trauma or recent spinal procedures.

The patient has a past medical history of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. The patient endorses chronic neck pain with a one year history of torticollis.

Personal Hx: Smokes 2 cigarettes daily and drinks alcohol occasionally. The patient’s social history was unremarkable. He denied any history of intravenous drug use, illicit substance use.

Family Hx: Diabetes from mother side.

On admission, the patient was febrile, but hemodynamically stable. Neurological exam revealed 3/5 strength in the bilateral lower extremities and 4/5 strength in the bilateral upper extremities. A positive Babinski reflex was noted on the right foot, along with diminished sensation in the left leg from the knee up. Given the acute neurological deterioration, emergent imaging and laboratory studies were conducted to determine the underlying etiology. Of note, this presentation was also suspicious for SEA.

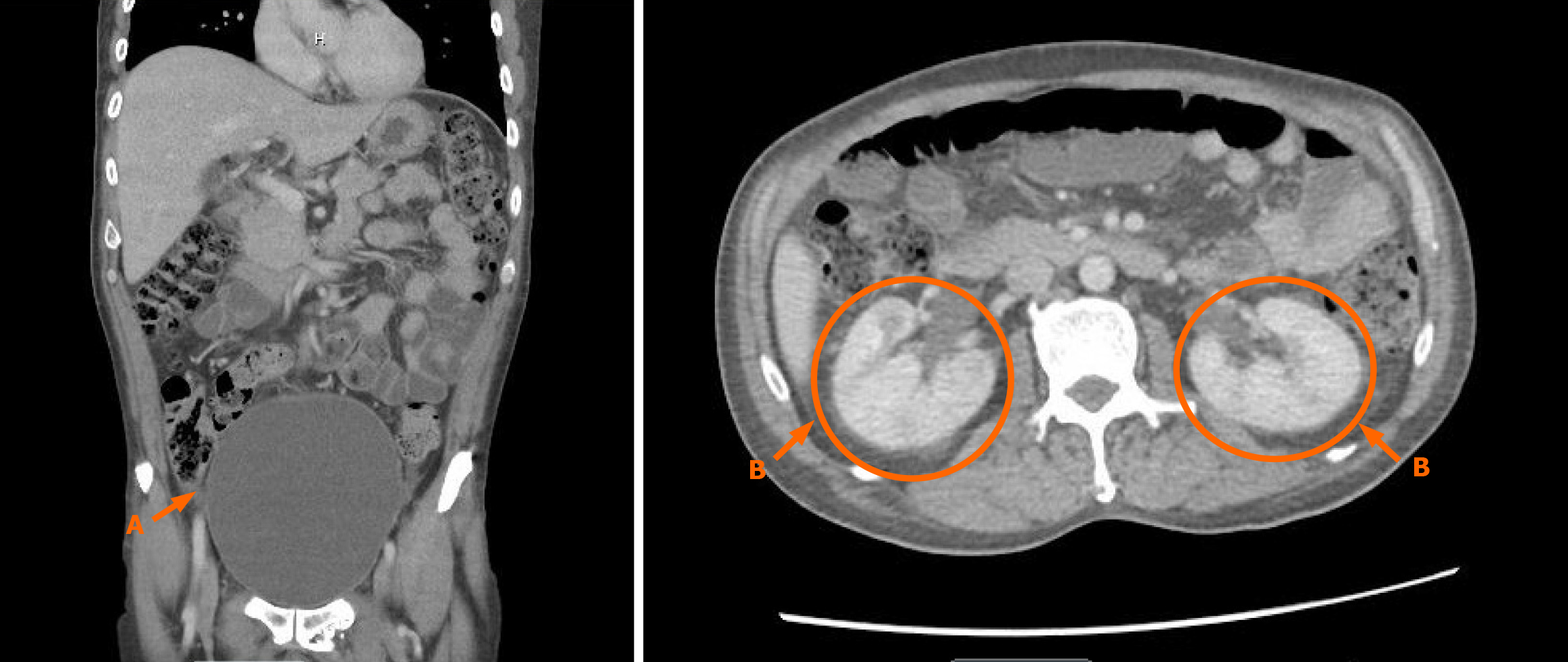

In the emergency department (ED), laboratory studies revealed leukocytosis (white blood counts: 20 × 10³/µL) and urinalysis was positive for leukocyte esterase and showed numerous white blood cells (> 200/hpf) (Tables 1 and 2). Blood and urine cultures were obtained. A lumbar puncture performed in the ED revealed clear cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with a low white blood cell count and elevated protein levels suggesting the possibility of GBS (Table 3). Prior to the lumbar puncture, a non-constrast computed tomography (CT) of the head was unremarkable. CT abdomen and pelvis with contrast demonstrated a markedly distended bladder, prominent ureters, and perinephric fat stranding, findings concerning for bladder outlet obstruction and acute pyelonephritis (Figure 1).

| On admission | 24 hours post-op | 1.5 months post-op discharge | Reference range | |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 130 | 144 | 138 | 133-144 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4 | 3 | 3.6 | 3.5-5.2 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 94 | 109 | 103 | 98-107 |

| Carbon dioxide (mEq/L) | 23.8 | 27.1 | 24.6 | 21.0-31.0 |

| Anion gap (mEq/L) | 12.2 | 7.9 | 9.6 | Lab value |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 11 | 7 | 11 | 7-25 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.6 | 0.55 | 0.36 | 0.7-1.30 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 248 | 118 | 96 | 70-99 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.7 | 7.9 | 8.4 | 8.6-10.3 |

| Phosphorous (mg/dL) | 3.2 | 4.6 | 2.5-4.5 | |

| Magnesium (mg/dL) | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.6-2.6 | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.9 | 3.2 | 3.5-5.7 | |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.3-1.0 | |

| AST (U/L) | 62 | 20 | 13-39 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 50 | 11 | 7-52 | |

| ALP (U/L) | 236 | 129 | 34-104 | |

| Lactic acid (mmol/L) | 1.7 | 0.5-2.0 | ||

| WBC (103/mcL) | 20.7 | 9.2 | 4.6 | 4.00-11.00 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.9 | 9.9 | 11.9 | 13.0-17.0 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 37.9 | 29.3 | 35.6 | 38.6-49.2 |

| Platelets (103/mcL) | 509 | 483 | 207 | 150-450 |

| Lab value | Result | Reference range |

| Urine pH | 7 | 5.0-8.0 |

| Protein, random urine (mg/dL) | 50 | 10-20 |

| Specific gravity | 1.02 | 1.005-1.025 |

| Urinalysis clarity | Turbid | Clear |

| Urinalysis color | Light orange | Colorless, yellow, light yellow |

| Urine glucose (mg/dL) | 300 | 30 |

| Urine blood (mg/dL) | 3+ | Negative |

| Urine RBC’s | > 200/hpf | 0-3/hpf |

| Urine bacteria | Many/hpf | Negative/hpf |

| Urine ketones (mg/dL) | 10 | Negative |

| Urine nitrites (mg/dL) | Negative | Negative |

| Urine WBC esterase (Leu/uL) | 500 | Negative |

| Urine WBC | > 200/hpf | 0-4/hpf |

| Lab value | Result | Reference range |

| Appearance | Clear | |

| CSF WBC (/mm3) | 2 | 0-5 |

| CSF RBC (/mm3) | 1 | |

| Fluid lymphocytes (%) | 26 | 40-80 |

| Fluid neutrophils (%) | 60 | 0-6 |

| Total count fluid differential | 100 | |

| CSF glucose (mg/dL) | 108 | 40-70 |

| CSF protein (mg/dL) | 222 | 15-45 |

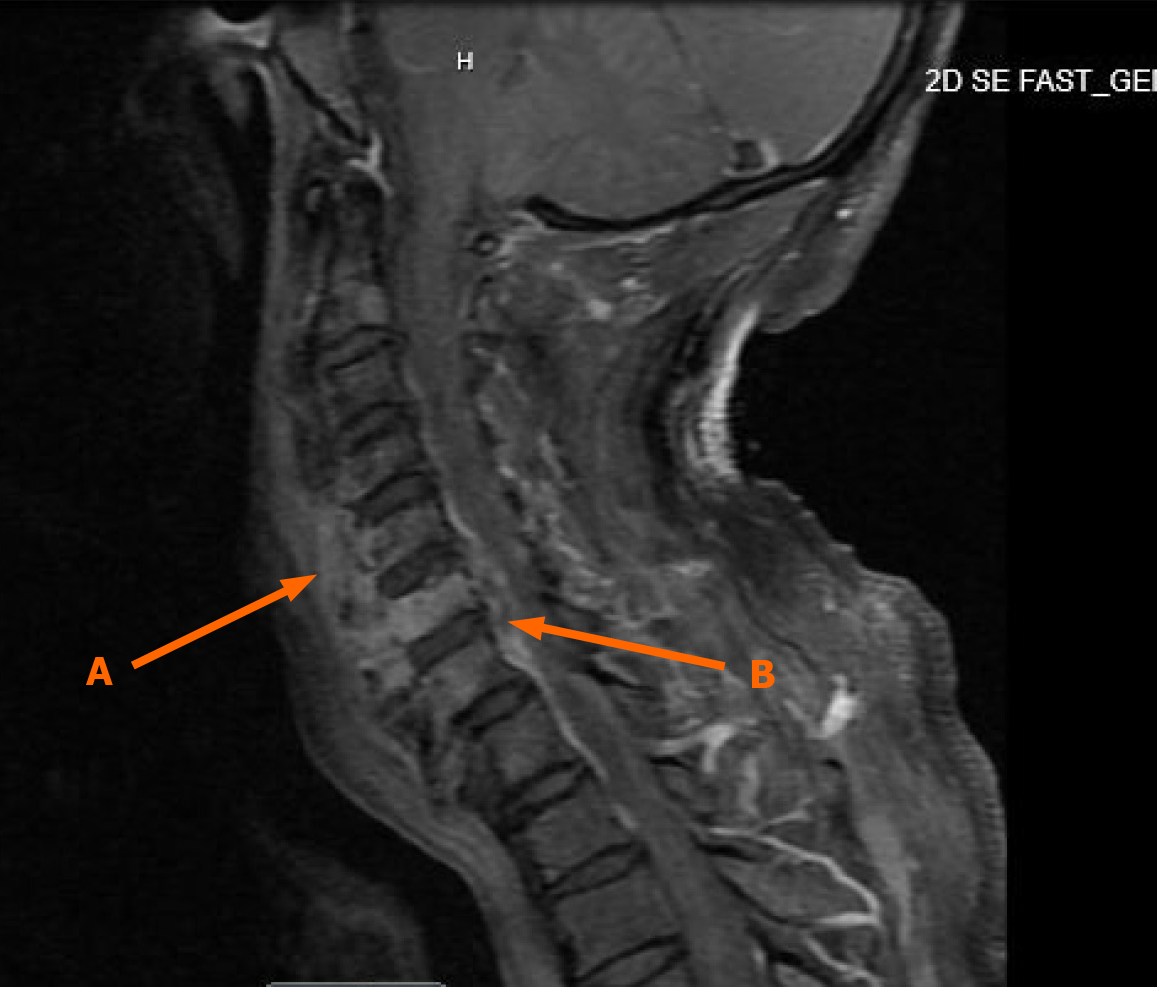

Given the acute neurological findings and CSF profile, neurology was consulted and recommended initiating intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) at 0.4 g/kg and obtaining a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and cervical spine (C-spine) with and without contrast. MRI of the brain was unremarkable. However, MRI of the C-spine demonstrated findings consistent with C5-C6 osteomyelitis and a C6-C7 epidural phlegmon with an associated epidural abscess and spinal cord compression (Figure 2).

Operative procedure performed: (1) C6 corpectomy (more than 70%), evacuation of epidural abscess decompression of spinal cord, nerve roots; (2) C5-C7 anterior instrumented arthrodesis; (3) Placement of biomechanical intervertebral device from inferior endplate of C5 to superior endplate of C7; (4) Placement of anterior cervical plate from C5-C7; (5) Use of allograft I factor; (6) Use of intraoperative fluoroscopy and interpretation of the films; and (7) SSEP and interpretation of the data. Postoperatively, the neurosurgical team recommended the continued cervical collar use for an additional 3-6 months.

Spinal epidural abscess.

A Foley catheter was placed to manage urinary retention. Given the urinary tract infection with clinical suspicion for acute pyelonephritis and possible meningitis, the patient was empirically started on intravenous cefepime and vancomycin. Blood and urine cultures subsequently grew MSSA, prompting a transition to an eight-week course of cefazolin via a peripherally inserted central catheter, per recommendations from the infectious disease team.

Given the concern for Guillain-Barré syndrome, neurology initiated a five-day course of IVIG; however, the patient showed no symptomatic improvement. CSF culture revealed no growth. MRI of the thoracic spine with and without contrast showed no evidence of discitis, osteomyelitis, or localized abscess. MRI of the cervical spine demonstrated findings consistent with C5-C6 osteomyelitis and a C6-C7 epidural abscess with associated spinal cord compression. Given these findings, the patient underwent urgent neurosurgical intervention, including C6 corpectomy and C5-C7 fusion three days after admission.

In the setting of recent cervical neck surgery using an anterior approach, the hospital course was further complicated by oropharyngeal dysphagia. The incidence of oropharyngeal dysphagia as a complication of C5-C6 anterior corpectomy is reported to be approximately 41.1% in the early post-operative period. This incidence is highest within the first week after surgery and decreases over time, with most cases resolving by 8-12 months post-operatively[11,12]. Some studies have shown that preoperative tracheal traction exercises as well as minimizing operative time and avoiding excessive or prolonged retraction of the esophagus and trachea are critical and could help prevent post-operative dysphagia[13-15].

An initial videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) was unsuccessful, necessitating the initiation of total parenteral nutrition. A repeat VFSS yielded similar results, prompting the placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube. Speech therapy intervention was initiated, focusing on swallowing rehabilitation. Physical therapy (PT) and Occupational therapy (OT) specialists worked closely with the patient post-operatively to improve his functional status and recommended acute inpatient rehabilitation. Social work services facilitated discharge planning to ensure continuity of care.

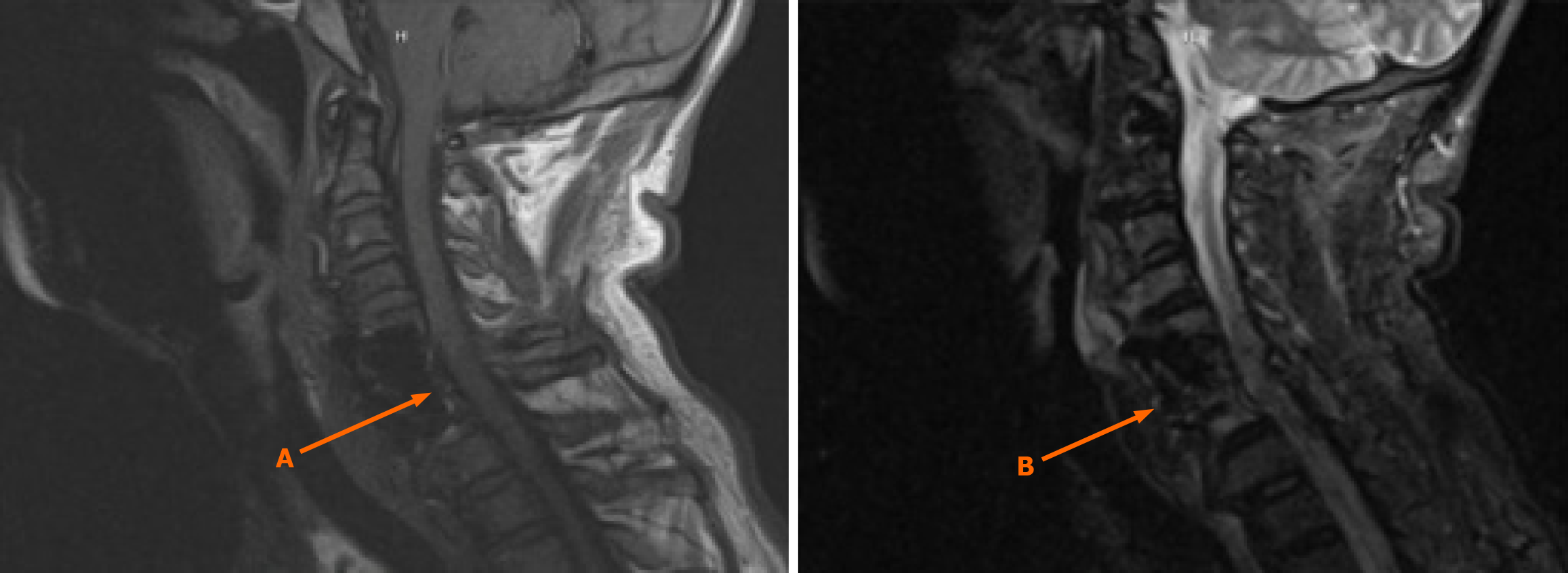

By the time of discharge, repeat blood cultures showed no evidence of bacteremia. To monitor treatment effectiveness and identify any potential complications, a follow-up MRI of the cervical spine with and without contrast was performed six weeks post-operatively, demonstrating resolution of the osteomyelitis and epidural abscess (Figure 3).

His neurological status showed significant improvement. Specifically, 5/5 strength in bilateral knee extensors, 3+/5 on Right hip flexor, 4/5 on Left hip flexor. Strength in shoulder adductors demonstrated 3/5 on the Right and 4/5 on the Left.

He was deemed appropriate for transfer to an inpatient rehabilitation facility for continued recovery. An outpatient follow-up plan was established to monitor his progress.

During his inpatient rehabilitation stay, the patient underwent intensive PT, OT, and speech-language pathology interventions. Significant functional recovery was observed, with notable improvements in motor strength and coordination compared to his initial presentation. Previously quadriplegic, the patient regained the ability to ambulate with assistance, managing approximately 10 steps unaided using a walker. His coordination also improved, allowing him to pivot, squat with eyes closed, grasp objects, write, and independently perform an increasing number of self-care tasks.

The patient demonstrated substantial progress in swallowing function throughout therapy. Initially requiring a PEG tube due to postoperative dysphagia, he ultimately regained the ability to swallow safely, leading to the removal of the PEG tube before discharge from the rehabilitation center.

Despite persistent urinary retention, necessitating discharge with an indwelling Foley catheter and scheduled urology follow-up, the patient exhibited remarkable neurological recovery. While mild weakness remained in the right upper extremity, strength and overall functionality had significantly improved. Additionally, PT and OT are addressing his chronic torticollis, for which he is also receiving Botox injections. Post-discharge, the patient continued to participate in outpatient PT and OT, further enhancing his recovery and functional independence.

SEA remains a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge due to its variable presentation and potential for devastating neurological outcomes. The classic triad of symptoms; fever, back pain, and neurological deficit, is only present in a minority of cases, often leading to delayed diagnosis[5]. This case highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion, especially in patients with risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, intravenous drug use, or recent spinal procedures. As demonstrated in this report, early recognition and intervention are critical in preventing permanent neurological impairment.

The likelihood of a spinal epidural abscess causing a urinary tract infection is low, as SEAs are most commonly caused by hematogenous spread from distant infections. In this case, cultures from OR grew Staphylococcus Aureus further buttressing the point.

The diagnostic approach to SEA has evolved significantly with the widespread availability of advanced imaging modalities in the present day. MRI with contrast remains the gold standard for diagnosis, allowing for early detection of the abscess and assessment of spinal cord compression. However, given the often nonspecific nature of initial symptoms, delays in obtaining imaging studies are common. In this case, the prolonged diagnostic timeline underscores the need for improved clinical awareness and prompt imaging in patients presenting with persistent back pain and bowel/bladder incontinence.

The management of SEA typically involves a combination of antimicrobial therapy and surgical decompression. The decision to proceed with surgery is influenced by several factors, including the presence of neurological deficits, abscess size, and response to conservative treatment[16]. In cases where the patient is neurologically intact or surgery poses high risk, medical management with prolonged intravenous antibiotics may be considered. However, studies have shown that delayed surgical intervention in patients with worsening neurological status are associated with a significant increase in likelihood of poor functional recovery[16]. The presented case exemplifies the delicate balance between conservative and surgical management, emphasizing the role of individualized treatment plans based on severity and patient comorbidities.

In resource-limited settings, managing SEA presents significant challenges due to constraints in diagnostic tools, surgical facilities, and specialized care. MRI may be unavailable or inaccessible, leading to reliance on clinical evaluation and less sensitive imaging modalities like CT or plain radiographs, which can delay diagnosis and treatment. Surgical intervention, often critical for decompression and drainage, may not be feasible due to limited neurosurgical expertise or operating room availability. Consequently, medical management with intravenous antibiotics becomes the primary treatment modality in resource-limited settings. However, studies indicate that conservative therapy has higher failure rates in patients with the aforementioned risk factors for SEA[17].

Socioeconomic factors further complicate SEA management in these settings. A retrospective study found that uninsured patients were significantly more likely to experience failure of conservative treatment compared to insured patients, highlighting disparities in healthcare access and outcomes[18]. To improve SEA management in resource-constrained areas, strategies such as training medical providers in early recognition, enhancing clinical awareness, and developing protocols for empiric antibiotic therapy are essential. Additionally, establishing appropriate referral systems for timely surgical intervention when necessary can help mitigate the risk for permanent neurological impairment.

Several case reports have highlighted the diverse presentations and etiologies of SEA: A 58-year-old man developed a cervical SEA combined with a cervical paravertebral soft tissue abscess. Patient presented with similar subsequent symptoms of neck pain and limb weakness. MRI confirmed abscesses at the C1 through C7 Levels. Surgical decompression and drainage led to complete recovery[19].

A 31-year-old patient with infectious cellulitis of the left hand progressed to SEA presenting with fever, back pain, muscle weakness, and urinary dysfunction. MRI confirmed the diagnosis, and laminectomy followed by antibiotics was the treatment course[20].

Two cases reported SEA formation following ureteroscopy in patients with histories of recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs). Both required surgical intervention[21].

These similar yet different cases demonstrate that SEA can arise from various sources, including UTIs and soft tissue infections, and can emerge with non-specific symptoms. Prompt recognition and keen intervention are essential to prevent permanent neurological damage.

In conclusion, this case highlights the critical importance of early recognition, timely imaging, and prompt intervention in the management of SEA. Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment, SEA remains a condition with substantial morbidity, with studies indicating that more than one-third of survivors suffer long-term neurological impairment. This underscores the need for ongoing rehabilitation and multidisciplinary follow-up to optimize recovery. Enhancing clinical awareness and implementing streamlined diagnostic protocols can help minimize delays in diagnosis and improve patient outcomes. Future research should focus on refining risk stratification models and optimizing treatment strategies to further reduce the burden of neurological complications associated with SEA.

Thanks to our families and friends who always supported us during the preparation for this case presentation.

| 1. | Sharfman ZT, Gelfand Y, Shah P, Holtzman AJ, Mendelis JR, Kinon MD, Krystal JD, Brook A, Yassari R, Kramer DC. Spinal Epidural Abscess: A Review of Presentation, Management, and Medicolegal Implications. Asian Spine J. 2020;14:742-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Balling H. Additional Sacroplasty Does Not Improve Clinical Outcome in Minimally Invasive Navigation-Assisted Screw Fixation Procedures for Nondisplaced Insufficiency Fractures of the Sacrum. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2019;44:534-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tompkins M, Panuncialman I, Lucas P, Palumbo M. Spinal epidural abscess. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:384-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Reihsaus E, Waldbaur H, Seeling W. Spinal epidural abscess: a meta-analysis of 915 patients. Neurosurg Rev. 2000;23:175-204; discussion 205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 569] [Cited by in RCA: 512] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Davis DP, Wold RM, Patel RJ, Tran AJ, Tokhi RN, Chan TC, Vilke GM. The clinical presentation and impact of diagnostic delays on emergency department patients with spinal epidural abscess. J Emerg Med. 2004;26:285-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Avilucea FR, Patel AA. Epidural infection: Is it really an abscess? Surg Neurol Int. 2012;3:S370-S376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bond A, Manian FA. Spinal Epidural Abscess: A Review with Special Emphasis on Earlier Diagnosis. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1614328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Darouiche RO. Spinal epidural abscess. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2012-2020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 472] [Cited by in RCA: 447] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Miller JM, Binnicker MJ, Campbell S, Carroll KC, Chapin KC, Gonzalez MD, Harrington A, Jerris RC, Kehl SC, Leal SM Jr, Patel R, Pritt BS, Richter SS, Robinson-Dunn B, Snyder JW, Telford S 3rd, Theel ES, Thomson RB Jr, Weinstein MP, Yao JD. Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2024 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clin Infect Dis. 2024;ciae104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Papaioannides D, Giotis C, Korantzopoulos P, Akritidis N. Brucellar spinal epidural abscess. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:2071-2072. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Ma Y, Sang P, Chen B, Li J, Bei D. The role of prevertebral soft tissue swelling in dysphagia after anterior cervical corpectomy fusion: change trends and risk factors. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24:720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ma Y, Sang P, Chen B. The role of esophageal area for dysphagia after anterior cervical corpectomy fusion: Change trends and risk factors. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e32974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Le HV, Javidan Y, Khan SN, Klineberg EO. Dysphagia After Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2024;32:627-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cho SK, Lu Y, Lee DH. Dysphagia following anterior cervical spinal surgery: a systematic review. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B:868-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu J, Hai Y, Kang N, Chen X, Zhang Y. Risk factors and preventative measures of early and persistent dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2018;27:1209-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Siddiq F, Chowfin A, Tight R, Sahmoun AE, Smego RA Jr. Medical vs surgical management of spinal epidural abscess. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2409-2412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gardner WT, Rehman H, Frost A. Spinal epidural abscesses - The role for non-operative management: A systematic review. Surgeon. 2021;19:226-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Page PS, Ammanuel S, Greeneway GP, Bunch K, Meisner LW, Brooks NP. Socioeconomic Disparities in Outcomes Following Conservative Treatment of Spinal Epidural Abscesses. Int J Spine Surg. 2023;17:185-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cao J, Fang J, Shao X, Shen J, Jiang X. Case Report: A case of cervical spinal epidural abscess combined with cervical paravertebral soft tissue abscess. Front Surg. 2022;9:967806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nery B, Filho CB, Nunes L, Quaggio E, Filho FB, Neto JA, Melo LR, Oliveira AC, Rabello R, Durand VR, Silva RR, Costa RE, Segundo JA. Acute Paraplegia Caused by Spinal Epidural Empyema Following Infectious Cellulitis of the Hand: Case Report and Literature Review. J Neurol Surg Rep. 2024;85:e29-e38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |