Published online May 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i15.2672

Revised: March 15, 2024

Accepted: April 3, 2024

Published online: May 26, 2024

Processing time: 81 Days and 22.8 Hours

Paraganglioma (PGL) located in the retroperitoneum presents challenges in diagnosis and treatment due to its hidden location, lack of specific symptoms in the early stages, and absence of distinctive manifestations on imaging.

A 56-year-old woman presented with a left upper abdominal mass discovered 1 wk ago during a physical examination. She did not have a history of smoking, alcohol consumption, or other harmful habits, no surgical procedures or infectious diseases, and had a 4-year history of hypertension. Upon admission, she did not exhibit fever, vomiting, or abdominal distension. Physical examination indicated mild percussion pain in the left upper abdomen, with no palpable enlargement of the liver or spleen. Laboratory tests and tumor markers showed no significant abnormalities. Enhanced computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the upper abdomen revealed a cystic solid mass in the left epigastrium measuring approximately 6.5 cm × 4.5 cm, with inhomogeneous enhancement in the arterial phase, closely associated with the lesser curvature of the stomach and the pancreas. The patient underwent laparoscopic resection of the retroperitoneal mass, which was successfully removed without tumor rupture. A 12-month postoperative follow-up period showed good recovery.

This case report details the successful laparoscopic resection of a retroperitoneal subclinical PGL, resulting in a good recovery observed at the 12-month follow-up. Interestingly, the patient also experienced unexpected cure of hypertensive disease.

Core Tip: Retroperitoneal subclinical paragangliomas (PGLs) are exceptionally uncommon. In this report, we present a case of PGL that was effectively managed by laparoscopic retroperitoneal lumpectomy. The patient showed excellent recovery at the 12-month postoperative follow-up and notably experienced resolution of her hypertensive condition. The management of this case serves as a valuable reference for addressing retroperitoneal PGLs.

- Citation: Kang LM, Yu FK, Zhang FW, Xu L. Subclinical paraganglioma of the retroperitoneum: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(15): 2672-2677

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i15/2672.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i15.2672

Paraganglioma (PGL), also known as extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma, is a rare tumor that develops in the paraganglia, specialized cells along the sympathetic or parasympathetic nervous system[1]. These tumors can be found in various locations such as the carotid body, aortic body, and other parasympathetic ganglia[2]. They can also occur in uncommon areas such as the skull base, mediastinum, and pelvis[3]. Retroperitoneal PGLs are particularly challenging to diagnose due to their asymptomatic nature and lack of specific imaging features[4]. We present a case of subclinical PGL in the left retroperitoneum that was successfully treated with surgery and confirmed by histopathological examination.

Before admission in January 2023, a 56-year-old woman attended the clinic due to a left upper abdominal mass found on physical examination 1 wk previously.

The patient was admitted to hospital with a 6.5 cm × 3.5 cm cystic solid mass in the left upper abdomen, as shown on abdominal ultrasound conducted 1 wk previously. The patient did not report any abdominal pain, distension, or discomfort.

The patient did not have a history of smoking, drinking, or other harmful habits, no known drug allergies or family history of genetic diseases, and no previous history of hepatitis, infectious diseases, or surgeries. She had been diagnosed with hypertension for 4 years and was currently taking oral amlodipine 2.5 mg and irbesartan 150 mg once daily.

No fever, vomiting, abdominal pain or distension were observed on admission. Physical examination revealed mild tenderness in the left upper abdomen, but no palpable abdominal mass.

Laboratory tests revealed no blood, coagulation, liver function, renal function, or tumor marker abnormalities, including carcinoembryonic antigen and glycan antigen 199. Blood dopamine level was 11.0 pg/mL, epinephrine was 31.60 pg/mL, and norepinephrine was 269.50 pg/mL. Her 24-h urine sample showed a dopamine level of 204.39 μg/24 h, epinephrine 17.47 μg/24 h, and norepinephrine 57.96 μg/24 h. Both plasma and urine catecholamine test results were normal. In addition, electrocardiogram, chest X-ray, and 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring were within the normal range.

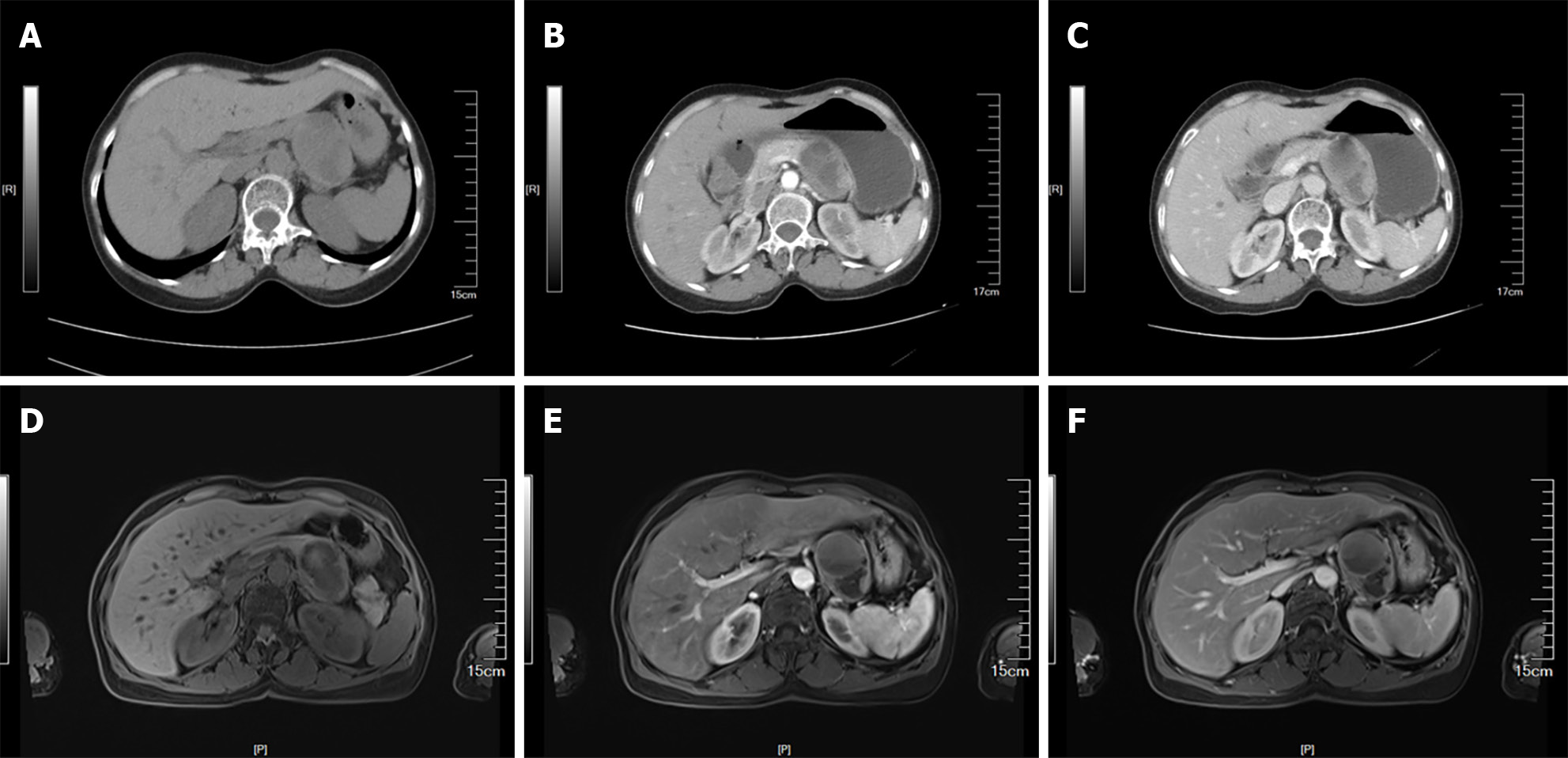

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the upper abdomen revealed a cystic solid mass measuring approximately 6.5 cm × 4.5 cm in the left upper abdomen. The mass exhibited inhomogeneous enhancement during the arterial phase and was closely associated with the lesser curvature of the stomach and pancreas, as well as with the celiac trunk arteries and splenic arteries (Figure 1).

Based on intraoperative blood pressure fluctuations and postoperative pathologic findings, the final diagnosis in this patient was a retroperitoneal subclinical PGL.

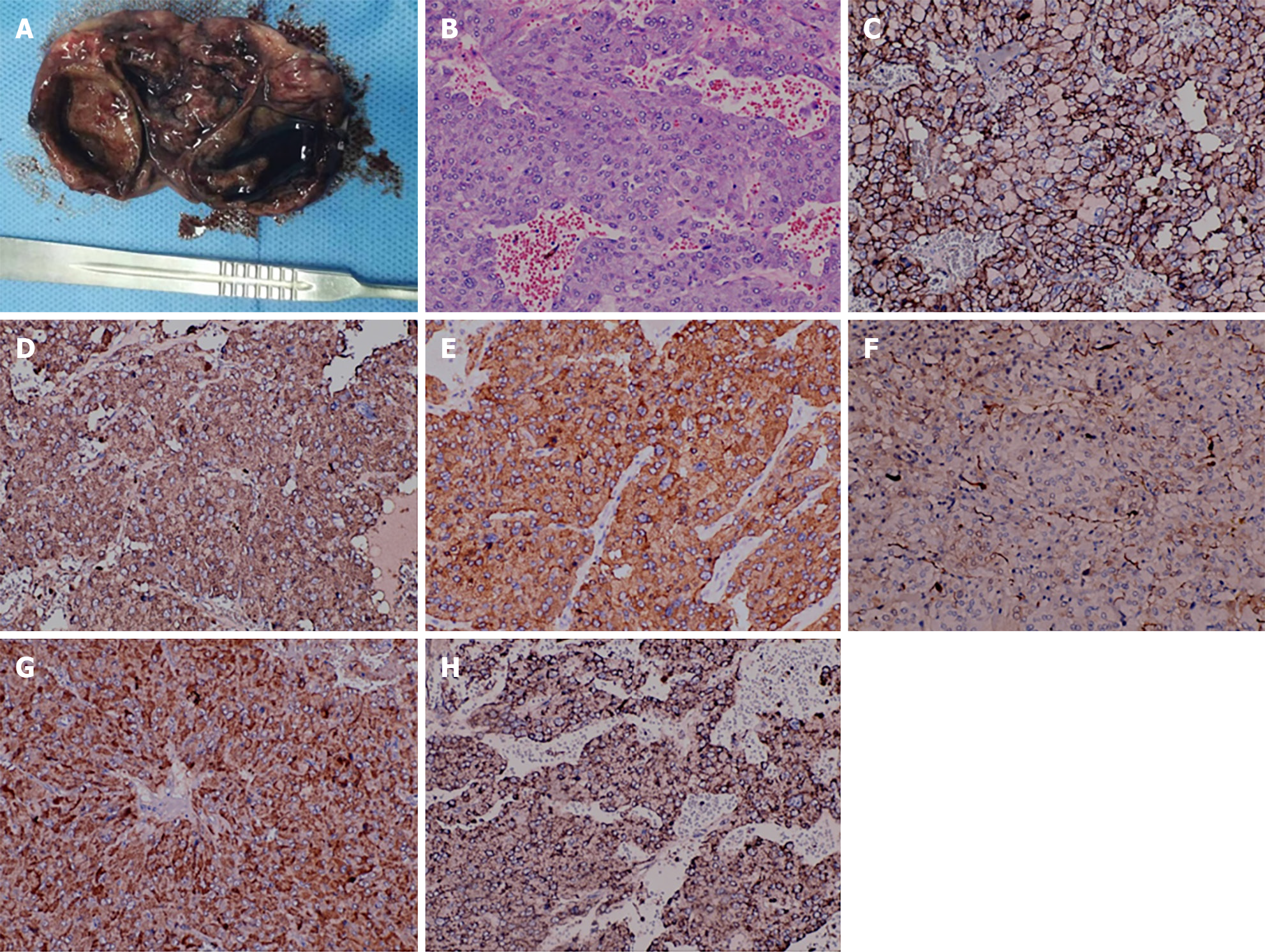

Following standardized preoperative preparation and perioperative management, the patient underwent laparoscopic exploration of the abdominal cavity in January 2023. Intraoperatively, our exploratory findings were consistent with the preoperative imaging findings, which revealed a mass clearly originating from the retroperitoneum and closely related to the lesser curvature of the stomach, the pancreas and the celiac trunk and splenic artery, leading to a successful retroperitoneal mass resection without tumor rupture. Postoperatively, examination revealed that the mass weighed 350 g and measured 6.5 cm × 40 cm × 3 cm, displaying a cystic solid appearance with a thickened cyst wall. Examination of the mass confirmed cystic solidity with dark red fluid inside the capsule (Figure 2).

Intraoperative blood pressure fluctuated between 100-220/70-180 mmHg, prompting the anesthesiologist to administer active treatment to stabilize blood pressure post-surgery. Subsequent immunohistochemistry revealed positive markers for cluster of differentiation 56 (CD56), chromogranin (CgA), synaptophysin (Syn), soluble protein-100 (S-100), insulinoma-associated protein 1 (INSM1), succinate dehydrogenase type B (SDHB), and negative markers for melanin-A antibody, cytokeratin-P, and delay of germination 1, leading to a pathological diagnosis of retroperitoneal PGL. Following surgery, the patient's blood pressure normalized and oral antihypertensive medications were gradually tapered. Follow-up appointments at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months showed normal results for blood pressure, physical examination, and repeat abdominal ultrasound.

PGLs are neuroendocrine tumors that originate from neural crest cells and are classified into non-functional, subclinical, and functional types based on the presence or absence of typical clinical symptoms caused by the secretion of catecholamines into the bloodstream[5]. Non-functional retroperitoneal PGLs do not exhibit typical clinical symptoms; patients may experience abdominal discomfort or physical examination findings due to tumor growth compressing adjacent organs[6]. The subclinical type involves catecholamine secretion, but in small amounts that do not induce typical symptoms, leading to blood pressure fluctuations during surgery. Functional PGLs are characterized by periodic cate

The incidence of PGL is low, making diagnosis relatively challenging due to the lack of specific clinical manifestations. Functional PGLs typically present with symptoms such as headache, palpitations, and hyperhidrosis (triad sign), but these neuroendocrine tumors often progress slowly, leading to delayed diagnosis. Patients may only seek medical attention when they experience extremely high blood pressure or symptoms of tumor compression, increasing the risk of complications[8]. Nonfunctional or subclinical PGLs primarily cause discomfort due to tumor compression. According to expert consensus[9], liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry is recommended for diagnosing pheochromocytoma and PGL by measuring plasma free catecholamine or urinary catecholamine concentrations. In this patient who was suspected of having pheochromocytoma, tests for plasma and urinary concentrations of dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine, were all within the normal range. However, the patient experienced significant blood pressure fluctuations during surgery, posing challenges for preoperative diagnosis and increasing intraoperative risks. Laparoscopic exploration of retroperitoneal space occupation has a magnifying effect, which facilitates the dissection of blood vessels and other fine structures, and has the advantages of less trauma and quicker recovery, but at the same time, there are also the risks of bleeding that are not easy to control, rupture of the tumour, and the need to be prepared for open surgery.

Imaging techniques such as color ultrasound, CT, and MRI lack specificity in distinguishing PGLs from other conditions such as giant lymph node hyperplasia, nerve sheath tumors, ganglion cell neuroma, and solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas[10]. Therefore, a combination of clinical manifestations, imaging, and laboratory examinations is typically needed to further clarify the nature of the mass. In this particular case, although ultrasound, CT, and MRI showed a cystic solid mass in the left upper abdomen, the origin of the mass and whether it was benign or malignant could not be determined. PGLs exhibit similar morphology regardless of their location and can be indistinguishable from adrenal gland pheochromocytomas. Microscopically, the tumor cells appear ovoid, cuboidal, or polygonal, larger than normal paragangliocytes, with granular basophilic cytoplasm, occasional melanin-like pigmentation, mild nuclear pleomorphism, and rare nuclear atypia. Tumor cells are organized in nests, cords, or adenoidal vesicles, with abundant blood sinuses between them that may be significantly dilated and hemorrhagic, sometimes showing vascular infiltration. The interstitium may exhibit sclerosis with fibroplasia, vitrification, or ossification[11]. Immunohistochemistry reveals that tumor cells express neuroendocrine markers such as neurospecific enolase, CgA, Syn, as well as calcitonin and vasoactive peptides. Support cells S-100 and glial fibrillary acidic protein are typically observed at the periphery of the cell clusters[12]. In this case, a PGL was not initially considered, but histological examination combined with immunohistochemistry for CD56, CgA, Syn, S-100, INSM1, and SDHB positivity ultimately led to the diagnosis of PGL.

PGLs can be categorized as either benign or malignant, with the majority being benign. Malignant PGLs represent a smaller percentage, ranging from 1% to 10%[13]. Distinguishing between benign and malignant forms based on morphological criteria is challenging. However, in cases of malignancy, certain characteristics such as tumor diameter exceeding 5 cm, presence of SDHB mutation, MYC associated factor X gene mutation, Ki67 index greater than 3%, noticeable cellular heterogeneity, atypical nuclear features, and localized necrosis are considered risk factors. Malignant PGLs have the potential to metastasize to various organs such as lymph nodes, bones, lungs, and liver, with metastasis serving as a key indicator of malignancy[14]. In the specific case discussed, the patient experienced normalization of blood pressure post-surgery, leading to the discontinuation of antihypertensive medication. Subsequent follow-up over 12 months showed a positive recovery outcome. Integrating intraoperative and pathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with a subclinical PGL. This case study provides valuable insights for the management of retroperitoneal PGLs.

A case of retroperitoneal subclinical PGL was successfully cured following surgical resection. This case serves as a valuable example of the management of retroperitoneal PGLs.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abuhijla F, Jordan S-Editor: Zheng XM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Karray O, Saadi A, Chakroun M, Ayed H, Cherif M, Bouzouita A, Slama MRB, Derouiche A, Chebil M. Retro-peritoneal paraganglioma, diagnosis and management. Prog Urol. 2018;28:488-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jain A, Baracco R, Kapur G. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma-an update on diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Pediatr Nephrol. 2020;35:581-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mete O, Asa SL, Gill AJ, Kimura N, de Krijger RR, Tischler A. Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Paragangliomas and Pheochromocytomas. Endocr Pathol. 2022;33:90-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 66.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kawanabe S, Katabami T, Oshima R, Yanagisawa N, Sone M, Kimura N. A rare case of multiple paragangliomas in the head and neck, retroperitoneum and duodenum: A case report and review of the literature. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1054468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lima JV Júnior, Kater CE. The Pheochromocytoma/Paraganglioma syndrome: an overview on mechanisms, diagnosis and management. Int Braz J Urol. 2023;49:307-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liu Z, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Kong L. Nonfunctional paraganglioma: A case report. Exp Ther Med. 2024;27:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tevosian SG, Ghayee HK. Pheochromocytoma/Paraganglioma: A Poster Child for Cancer Metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1779-1789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Meijs AC, Snel M, Corssmit EPM. Pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma crisis: case series from a tertiary referral center for pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Hormones (Athens). 2021;20:395-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lenders JWM, Kerstens MN, Amar L, Prejbisz A, Robledo M, Taieb D, Pacak K, Crona J, Zelinka T, Mannelli M, Deutschbein T, Timmers HJLM, Castinetti F, Dralle H, Widimský J, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Eisenhofer G. Genetics, diagnosis, management and future directions of research of phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma: a position statement and consensus of the Working Group on Endocrine Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2020;38:1443-1456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rusyn L, Kohn B. Succinate-Dehydrogenase Deficient Paragangliomas/Pheochromocytomas: Genetics, Clinical Aspects and Mini- Review. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2017;14:312-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lei J, Qu T, Cha L, Tian L, Qiu F, Guo W, Cao J, Sun C, Zhou B. Clinicopathological characteristics of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma and screening of prognostic markers. J Surg Oncol. 2023;128:510-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Juhlin CC. Challenges in Paragangliomas and Pheochromocytomas: from Histology to Molecular Immunohistochemistry. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:228-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hamidi O. Metastatic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: recent advances in prognosis and management. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019;26:146-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jimenez C, Fazeli S, Román-Gonzalez A. Antiangiogenic therapies for pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2020;27:R239-R254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |