Published online Oct 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i29.7162

Peer-review started: June 27, 2023

First decision: August 20, 2023

Revised: September 1, 2023

Accepted: September 22, 2023

Article in press: September 22, 2023

Published online: October 16, 2023

Processing time: 108 Days and 12.9 Hours

Primary aortoduodenal fistula is a rare cause of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding consisting of abnormal channels between the aorta and GI tract without previous vascular intervention that results in massive intraluminal hemorrhage.

A 67-year-old man was hospitalized for coffee ground vomiting, tarry stools, and colic abdominal pain. He was repeatedly admitted for active GI bleeding and hypovolemic shock. Intermittent and spontaneously stopped bleeders were undetectable on multiple GI endoscopy, angiography, computed tomography angiography (CTA), capsule endoscopy, and 99mTc-labeled red blood cell (RBC) scans. The patient received supportive treatment and was discharged without signs of rebleeding. Thereafter, he was re-admitted for bleeder identification. Repeated CTA after a bleed revealed a small aortic aneurysm at the renal level contacting the fourth portion of the duodenum. A 99mTc-labeled RBC single-photon emission CT (SPECT)/CT scan performed during bleeding symptoms revealed active bleeding at the duodenal level. According to his clinical symptoms (intermittent massive GI bleeding with hypovolemic shock, dizziness, dark red stool, and bloody vomitus) and the abdominal CTA and 99mTc-labeled RBC SPECT/CT results, we suspected a small aneurysm and an aortoduodenal fistula. Subsequent duodenal excision and duodenojejunal anastomosis were performed. A 7-mm saccular aneurysm arising from the anterior wall of the abdominal aorta near the left renal artery was identified. Percutaneous intravascular stenting of the abdominal aorta was performed and his symptoms improved.

Our findings suggest that 99mTc-labeled RBC SPECT/CT scanning can aid the diagnosis of a rare cause of active GI bleeding.

Core Tip: We describe a 67-year-old man was recurrently admitted due to gastrointestinal (GI) active bleeding and hypovolemic shock. According to clinical symptoms, abdominal computed tomography (CT) angiography, and 99mTc-red blood cell single-photon emission CT/CT scan, duodenal bleeding may be caused by the small aneurysm, and primary aortoduodenal fistula was highly suspected. Then he underwent duodenum excision and duodenum-jejunum anastomosis. The symptoms of GI bleeding improved postoperatively.

- Citation: Kuo CL, Chen CF, Su WK, Yang RH, Chang YH. Rare finding of primary aortoduodenal fistula on single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography of gastrointestinal bleeding: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(29): 7162-7169

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i29/7162.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i29.7162

In the scientific literature between 1951 and 2010, 253 cases of primary aortoduodenal fistula (PADF) were reported. PADF is difficult to diagnose clinically, as the clinical characteristics include gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding with hematemesis and melena once patients reach a severely deteriorated condition. Despite the low incidence of PADF, delays in diagnosis and treatment have historically been associated with extremely high mortality[1-10]. To treat GI bleeding, the bleeding site must be localized, usually by using endoscopy. Other methods include angiography, computed tomography (CT) angiography (CTA), capsule endoscopy, and 99mTc-labeled red blood cell (RBC) scanning, each of which has its limitations[11-17].

Here, we present the first case of PADF at our hospital and discuss its diagnosis and management. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Mackay Memorial Hospital (No. 23MMHIS055e).

A 67-year-old man was hospitalized after experiencing coffee ground vomiting, tarry stools, and colic abdominal pain.

The patient had severe anemia due to active GI bleeding.

The patient experienced long-term GI hemorrhage, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and renal dysfunction.

The patient’s personal and family history was unremarkable.

He was repeatedly admitted because of active GI bleeding and hypovolemic shock. Intermittent and spontaneously stopped bleeders were difficult to detect after multiple GI endoscopy, angiography, CTA, capsule endoscopy, and 99mTc-labeled RBC scan sessions. The patient received supportive treatment each time and was discharged without any signs of rebleeding.

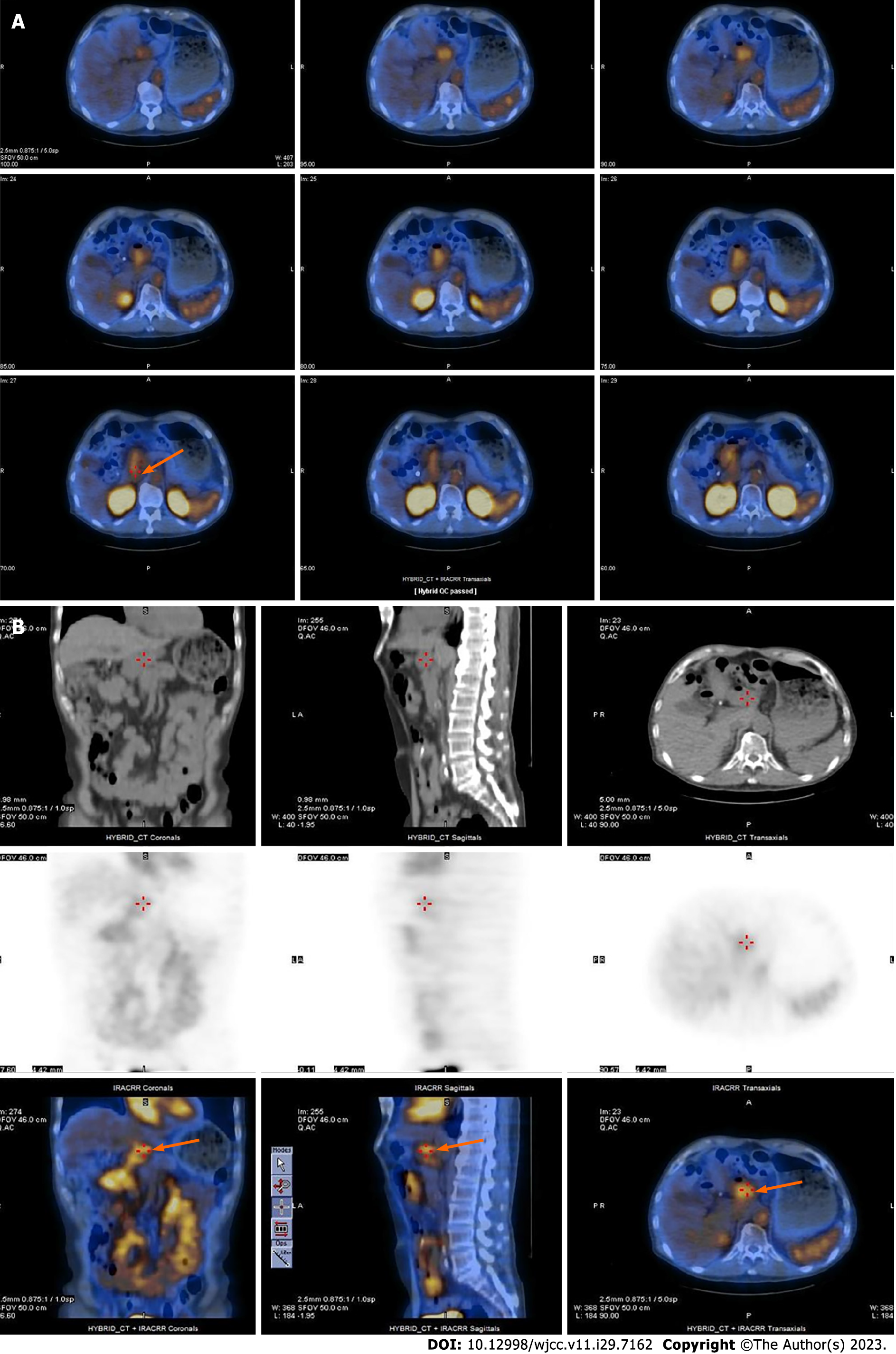

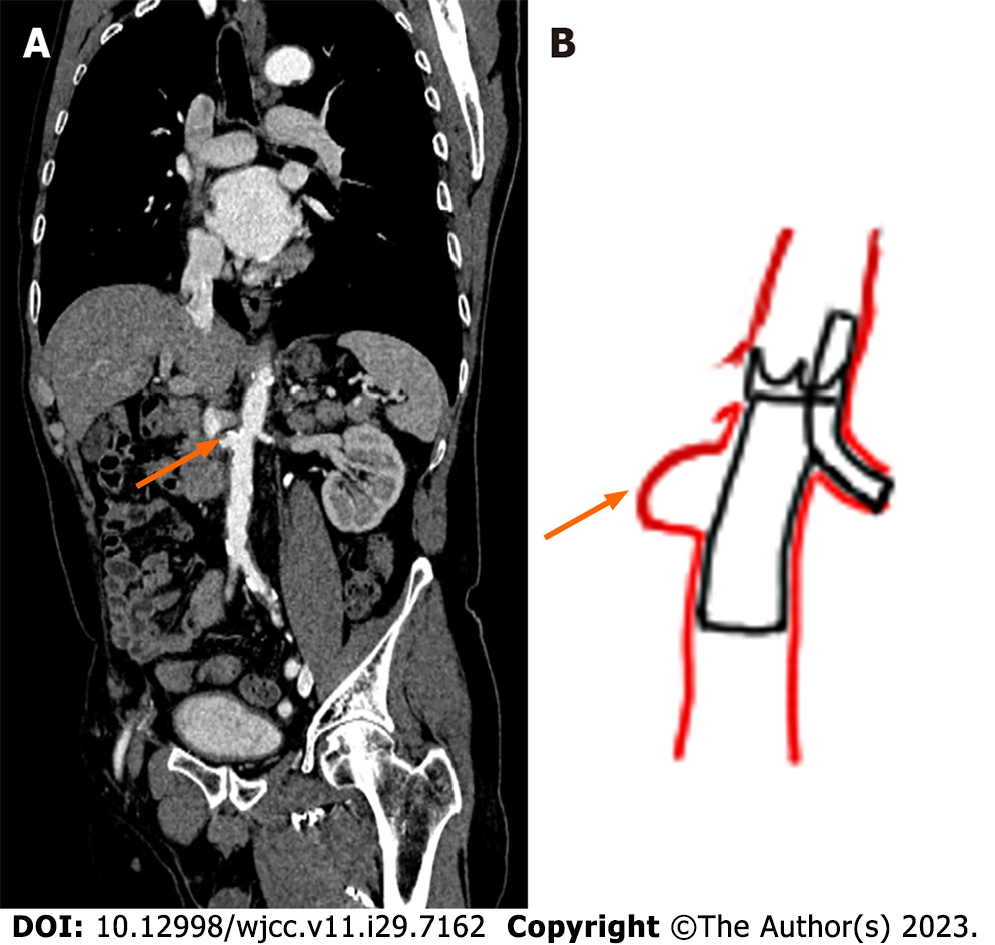

Blood tests showed low hemoglobin and hematocrit levels.

Initially, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed gastric ulcers and suspected Dieulafoy lesions (Figure 1A). Furthermore, small bowel endoscopy revealed several shallow ulcers with pigmented spots in the middle part of the jejunum and proximal ileum; thus, a hemorrhage of small bowel origin was suspected (Figure 1B). EGD also revealed a duodenal diverticulum in the third portion (Figure 1C). However, recurrent episodes of bleeding occurred, and 99mTc-labeled RBC and colon endoscopy were performed. The 99mTc-labeled RBC scan showed radioactivity in the middle ascending colon to the hepatic flexure 17.5 h after a radiotracer injection; however, since the interval between images was 5.5 h, the intermittent intestinal bleeding could have been from the proximal to ascending colon, cecum, ileum, or jejunum (Figure 1D). Follow-up colonoscopy revealed two outpunches with dark brown content and mild oozing in the transverse colon for which bleeding was highly suspected (Figure 1E). The patient underwent multiple imaging examinations during this period; however, he experienced recurrent GI bleeding and was admitted to the hospital. Therefore, we believed that he should be re-admitted to enable identification of the bleeder. CTA performed soon after the bleeding episode revealed a small aortic aneurysm at the renal level in contact with the fourth portion of the duodenum (Figure 2A). A 99mTc-labeled RBC scan was performed while the patient still had bleeding symptoms and showed active bleeding at the duodenal level in the lateral view at 19 h; other anterior views showed no significant bleeding points (Figure 2B). Subsequent confirmation using single-photon emission CT/CT scan revealed that the aortic fistula was pumping blood into the duodenum (Figure 3).

Based on the patient’s clinical symptoms and the GI endoscopy (colonoscopy, EGD, single balloon enteroscopy, and capsular enteroscopy), abdominal CTA, and 99mTc-labeled RBC single-photon emission CT (SPECT)/CT scan findings, duodenal bleeding caused by a small aneurysm and PADF were highly suspected.

The patient underwent duodenal excision and duodenojejunal anastomosis. A 7-mm saccular aneurysm arising from the anterior wall of the abdominal aorta near the left renal artery was detected intraoperatively. Percutaneous intravascular stenting of the abdominal aorta was then performed. The operative procedure is illustrated in Figure 4.

The patient’s symptoms of GI bleeding improved postoperatively.

EGD is the first step in the diagnosis of active GI bleeding. However, it has a low detection rate for aortoenteric fistulas because it cannot consistently visualize the distal parts of the duodenum. CT has the highest detection rate for aortoenteric fistulas and is helpful for patients whose bleeders are not identified on initial EGD or whose bleeding continues after treatment. The 99mTc-labeled RBC scan is often used when the bleeding amount and frequency are low. It has low resolution and frequently has a marked lag between the onset of bleeding, but can be continuously monitored for hours. In this case, we showed that 99mTc-labeled RBC SPECT/CT can localize bleeding if the patient has active GI bleeding and can aid the diagnosis.

PADF is extremely rare, with an autopsy incidence of 0.04%-0.07%[1-2]. A fistula most commonly originates between an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) and the duodenum. Because of the close approximation and fixed nature of the duodenum, the expanding nature of the AAA causes irritation and inflammation, resulting in fistulization over time. Thus, PADF is prone to occur in the third part of the duodenum, accounting for two-thirds of all PADF cases. The remaining one-third occurs in the fourth part of the duodenum[3-7]. Classical presentations of PADF include upper GI bleeding (64%), abdominal pain (32%), and a pulsatile abdominal mass (25%)[8]. Although GI bleeding is almost invariably present, the first few episodes are usually mild and self-limiting. In the beginning, these so-called herald bleeds may be the only manifestations of fistulization. A high proportion of the reported cases had long periods (up to months) of sparse and self-limiting episodes[9]. In such cases, it is easily misinterpreted as chronic GI bleeding, which is easily underestimated by patients or confused with peptic ulcer disease by physicians. Consequently, herald bleeds may remain unnoticed until the sudden occurrence of a massive hemorrhage precipitates hemorrhagic shock[10]. These symptoms are very similar to those observed in our case, in which the patient experienced intermittent GI bleeding for approximately 1 year.

The timely and accurate diagnosis of PADF may be challenging because of the insidious episodes of GI bleeding, which are frequently underdiagnosed until massive hemorrhaging occurs. Therefore, diagnosing PADF can be challenging not only because of the variation and non-specificity of symptoms but also because it is difficult to definitively identify using imaging modalities. Saers and Scheltinga[9] analyzed the detection rate of primary aortoenteric fistulas in 81 patients using diagnostic tools (Table 1). EGD is the first step in the diagnosis of upper-GI bleeding. However, in most cases, only the proximal portion of the duodenum is visualized. This results in low sensitivity in diagnosing aortoenteric fistulas, with a detection rate of 25%[5,7,9]. The most valuable diagnostic tool for PADF is CTA with intravenous contrast since it can reveal all associated common findings: AAA, absence of a clear separation between the duodenal and aortic walls, signs of retroperitoneal inflammation, and air in the retroperitoneum or thrombus[4,5,7]. Angiography can demonstrate extravasation of the contrast agent into the bowel; however, contrast medium is present in the GI tract in only approximately one-quarter of these patients. Therefore, angiography is not reliable for diagnosing PADF[4,9]. Other modalities, such as ultrasound, colonoscopy, enteroclysis, 99mTc-labeled RBC scanning, and colonic radiography, do not contribute to the diagnosis of PADF and are of limited value[9].

| Diagnostic tool | Detection rate (%) |

| Esophagogastroduodenoscopy | 25 |

| Computed tomography | 61 |

| Angiography | 26 |

| Ultrasound | 0 |

| Colonoscopy | 10 |

| Enteroclysis | 13 |

| 99mTc-red blood cell scan | 14 |

| Colonic radiography | 0 |

The abovementioned studies indicated that 99mTc-labeled RBC scans are not significantly helpful for the detection of PADF. Precise anatomical localization of the bleeding site is not possible because of the limited resolution of scintigraphy, and there is frequently a marked lag between bleeding onset and clinical findings. An advantage of using 99mTc-labeled RBC is that it can continuously monitor the entire GI tract for up to approximately 24 h. Additionally, 99mTc-labeled RBC scanning is a noninvasive method that can detect bleeding with high sensitivity, localize the bleeding area, and help approximate the bleeding volume. This advantage of continuous imaging increases the likelihood of detecting intermittent bleeding over other techniques that are limited to a single time point or periodic sampling[11-14].

In this case, CTA first identified a small aortic aneurysm at the renal level connected to the fourth portion of the duodenum. A 99mTc-labeled RBC scan was performed when the patient still had hemorrhagic symptoms. We also performed a SPECT/CT scan because it is better than planar images are at diagnosing bleeding points and collecting information about the etiology[16,17]. Moreover, SPECT/CT may contribute to confirming aortic aneurysms and determining their clinical significance[17]. In conclusion, if a bleeding site is identified on 99mTc-labeled RBC planar imaging, a SPECT/CT study is recommended for confirmation. Furthermore, review of the CT scans performed 1 year prior revealed that the aneurysm had existed, but had gone undetected because of its small size and the absence of aneurysmal wall loss, air leak in the retroperitoneum, or inflammation. Consequently, the PADF in this patient was easily missed and could only be detected using CTA.

EGD is the first step in the diagnosis of active GI bleeding. However, it has a low detection rate for aortoenteric fistulas because the distal parts of the duodenum are not always visualized. CT has the highest detection rate for aortoenteric fistulas and is helpful for patients whose bleeders are not identified on initial EGD or bleeding continues after treatment. Thus, 99mTc-labeled RBC scans are often performed when the bleeding amount and frequency are low. It has low resolution and frequently has a marked lag between the onset of bleeding but can be continuously monitored for hours. In this case, 99mTc-labeled RBC SPECT/CT could localize GI bleeding and aided the diagnosis of PADF.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chen Q, China; Demetrashvili Z, Georgia; Redkar RG, India S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Šumskienė J, Šveikauskaitė E, Kondrackienė J, Kupčinskas L. Aorto-duodenal fistula: a rare but serious complication of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. A case report. Acta Med Litu. 2016;23:165-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | St Stoyanov G, Dzhenkov D, Petkova L. Primary aortoduodenal fistula: a rare cause of massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Autops Case Rep. 2021;11:e2021301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rodrigues dos Santos C, Casaca R, Mendes de Almeida JC, Mendes-Pedro L. Enteric repair in aortoduodenal fistulas: a forgotten but often lethal player. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28:756-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Alzobydi AH, Guraya SS. Primary aortoduodenal fistula: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:415-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Bissacco D, Freni L, Attisani L, Barbetta I, Dallatana R, Settembrini P. Unusual clinical presentation of primary aortoduodenal fistula. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2015;3:170-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Beuran M, Negoi I, Negoi RI, Hostiuc S, Paun S. Primary Aortoduodenal Fistula: First you Should Suspect it. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;31:261-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Georgeades C, Zarb R, Lake Z, Wood J, Lewis B. Primary Aortoduodenal Fistula: A Case Report and Current Literature Review. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;74:518.e13-518.e23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sweeney MS, Gadacz TR. Primary aortoduodenal fistula: manifestation, diagnosis, and treatment. Surgery. 1984;96:492-497. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Saers SJF, Scheltinga MRM. Primary aorto-enteric fistula. Br J Surg. 2005;92:143-152. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lin TC, Tsai CL, Chang YT, Hu SY. Primary aortoduodenal fistula associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm with presentation of gastrointestinal bleeding: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2018;18:113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dam HQ, Brandon DC, Grantham VV, Hilson AJ, Howarth DM, Maurer AH, Stabin MG, Tulchinsky M, Ziessman HA, Zuckier LS. The SNMMI procedure standard/EANM practice guideline for gastrointestinal bleeding scintigraphy 2.0. J Nucl Med Technol. 2014;42:308-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Winzelberg GG, McKusick KA, Strauss HW, Waltman AC, Greenfield AJ. Evaluation of gastrointestinal bleeding by red blood cells labeled in vivo with technetium-99m. J Nucl Med. 1979;20:1080-1086. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Cherian MP, Mehta P, Kalyanpur TM, Hedgire SS, Narsinghpura KS. Arterial interventions in gastrointestinal bleeding. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26:184-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zink SI, Ohki SK, Stein B, Zambuto DA, Rosenberg RJ, Choi JJ, Tubbs DS. Noninvasive evaluation of active lower gastrointestinal bleeding: comparison between contrast-enhanced MDCT and 99mTc-labeled RBC scintigraphy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:1107-1114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Boal Carvalho P, Rosa B, Moreira MJ, Cotter J. New evidence on the impact of antithrombotics in patients submitted to small bowel capsule endoscopy for the evaluation of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2014;2014:709217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Otomi Y, Otsuka H, Terazawa K, Yamanaka M, Obama Y, Arase M, Otomo M, Irahara S, Kubo M, Uyama N, Abe T, Harada M. The diagnostic ability of SPECT/CT fusion imaging for gastrointestinal bleeding: a retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Soyluoğlu S, Korkmaz Ü, Özdemir B, Durmuş Altun G. The Diagnostic Contribution of SPECT/CT Imaging in the Assessment of Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Especially for Previously Operated Patients. Mol Imaging Radionucl Ther. 2021;30:8-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |