Published online Jul 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i19.4640

Peer-review started: January 15, 2023

First decision: February 1, 2023

Revised: February 11, 2023

Accepted: June 9, 2023

Article in press: June 9, 2023

Published online: July 6, 2023

Processing time: 166 Days and 7 Hours

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC), a rare and unique variant of liver cancer, can be divided into lymphoepithelioma-like hepatocellular carcinoma and lymphoepithelioma-like intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Dense lymphocytic infiltration is its characteristic pathological feature. In recent years, the number of reported cases of this type has increased each year. Studies have shown that lymphoepithelioma-like cholangiocarcinoma occurs more frequently in Asian women; LELC is associated with Epstein–Barr virus infection of liver cells of epithelial origin. Existing research shows that the prognosis of this tumour is good.

A 38-year-old female patient was hospitalized after 3 mo of abdominal pain and nausea. She had been infected with hepatitis B virus more than 10 years prior. The patient was hospitalized on January 21, 2022. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a 36 mm × 28 mm mass under the envelope of the left inner lobe of the liver. No metastasis of lymph nodes or other organs was observed. After left hemihepatectomy, biopsy and immunohistochemistry yielded a final diagnosis of lymphoepithelial hepatocellular carcinoma. After 12 mo of outpatient follow-up and chemotherapy, no tumour metastases were found on the latest computed tomography examination.

Herein, the patient was treated surgically and then followed up as an outpatient for 12 mo. This case will further expand our overall knowledge of the diagnosis and treatment of this rare tumor.

Core Tip: Primary hepatocellular lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC) is a rare disease. We review the relevant literature, and only a few clinical cases have been reported worldwide. The patient in this case report was eventually diagnosed with primary hepatocellular LELC based on her family history, magnetic resonance imaging scans, and immunohistochemical findings. Herein, we summarize and discuss this case and review the pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of primary hepatocellular LELC.

- Citation: Tang HT, Lin W, Zhang WQ, Qian JL, Li K, He K. CK5/6-positive, P63-positive lymphoepithelioma-like hepatocellular carcinoma: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(19): 4640-4647

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i19/4640.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i19.4640

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC) is a tumor consisting of undifferentiated epithelial cells with a distinct lymphocytic infiltrate. This term was originally used to describe tumors of the nasopharynx[1-5]; however, this tumor has also been reported to be found in the lung, breast, prostate, bladder, uterus, and liver[6]. LELC is a rare and unique variant of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with distinct epidemiological and pathological features possessing a large lymphocytic infiltration. Available studies suggest that this type of tumor has a good prognosis[7,8], and primary LELC of the liver is rare[9]. LELC was recognized as a unique variant of liver cancer by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2010[10]. As with LELC at most other sites, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection plays a crucial role in the carcinogenesis of liver LELC, and EBV infection can be detected in the vast majority of LELC cases. These results suggest that EBV infection plays an important role in LELC tumorigenesis and development. Lymphoepithelioma-like cholangiocarcinoma (LEL-ICC) formation is closely related to EBV infection[11]. The presence of EBV was also detected in the intrahepatic cholangiocytic LELC in this case. Hepatocellular LELC has no special clinical manifestations; most patients have a history of hepatitis, but a few do not. Histologically, the tumour is infiltrative; specifically, it infiltrates the mucosa in the form of irregular islands, nests, sheets, or single cells. The nests and stroma were filled with mature lymphocytes and plasma cells. Tumour cells have a single vesicular nucleus, a round to ovoid shape, obvious nucleoli, and an eosinophilic cytoplasm. The cells have a syncytial appearance, with no clear boundaries separating them. The tumour cells may also present a thick fusiform shape, and the nuclei may be arranged in a way that resembles flowing water. Most tumour cells are positive for CKL8 and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). The immunohistochemical markers of infiltrated lymphocytes suggest polyclonal expression. Combining and reviewing the literature on the treatment of LELC, a case of hepatic LELC in a 38-year-old woman is reported here; we hope this report will further improve the diagnosis and treatment of patients with this condition.

A 38-year-old woman was admitted to Zhongshan People's Hospital of Guangdong Province on January 21, 2022, with complaints of dull epigastric pain for 1 wk.

The patient began to have dull pain in the upper abdomen without any obvious cause. The pain was a persistent sense of distension that did not radiate to any other locations, and there was no actual, palpable distension of the abdomen. The patient had no fever, chills, dizziness, headache, cough, expectoration, diarrhoea, vomiting, bloody or black stools, etc.

This patient had been infected with hepatitis B virus for more than 10 years and had not been given symptomatic treatment. She had no other significant medical history.

There was no other special personal history or family history of disease.

The patient presented with persistent epigastric pain that did not radiate elsewhere.

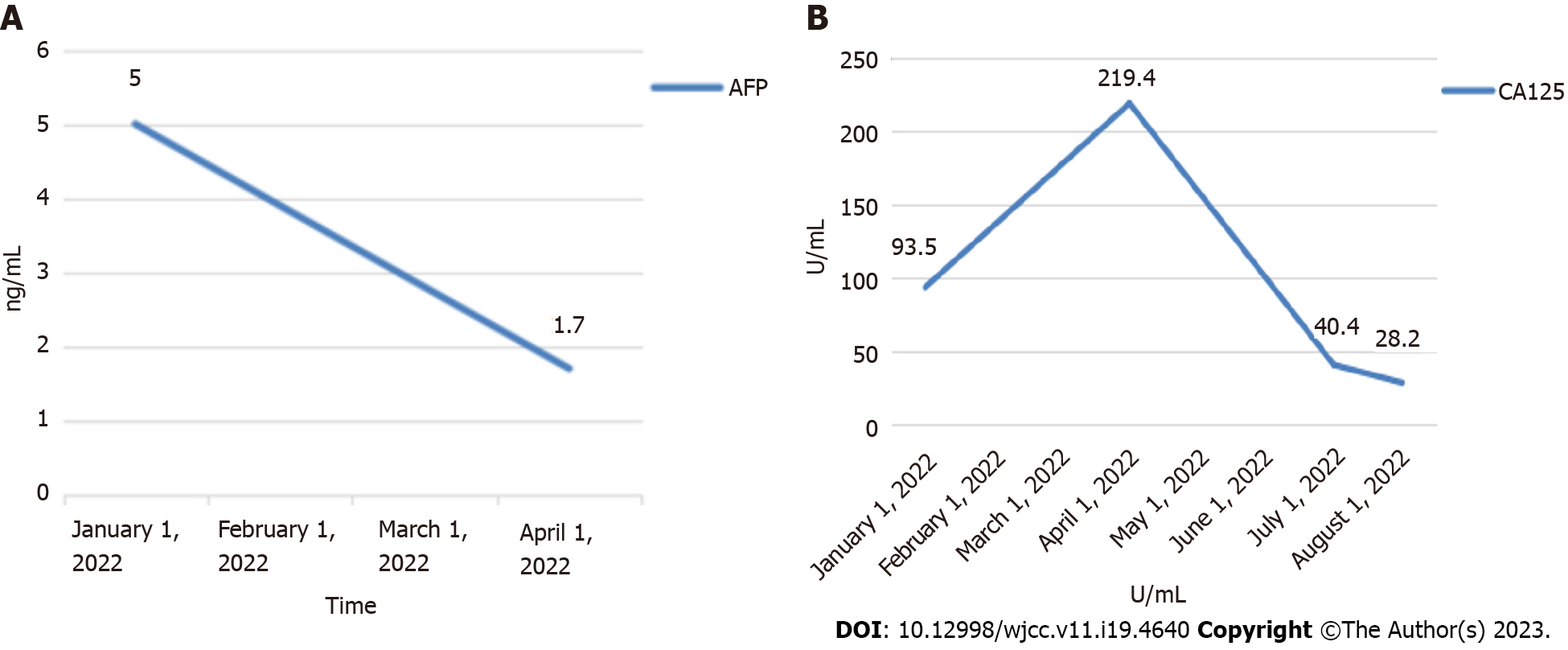

The patient’s laboratory results were as follows: Protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II (PIVKA-Ⅱ): 38.6 (normal range: 20-40 mAU/mL); AFP: 5 (normal range: 0.0-8.1 ng/mL); carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA): 1.70 (normal range: 0.0-5.0 ng/mL); carbohydrate antigen 125: 93.50 (normal range: 0.0-35.0 U/mL); carbohydrate antigen199 (CA19-9): 165.50 (normal range: 0.0-37.0 U/mL); EBV-DNA: 1.62E+02 copies/mL (normal range: < 100 copies/mL); hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb): (+) (normal range: < 10.00 mIU/mL); hepatitis B e antibody (HBeAb): (+) (normal range: > 1.00 cut off index [COI]); hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb): (+) (normal range: < 1.00 COI); alanine aminotransferase (ALT): 5 (normal range: 7-40 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase (AST): 12 (normal range: 13-35 U/L); albumin(Alb): 37.90 (normal range: 40.0-55.0 g/L).

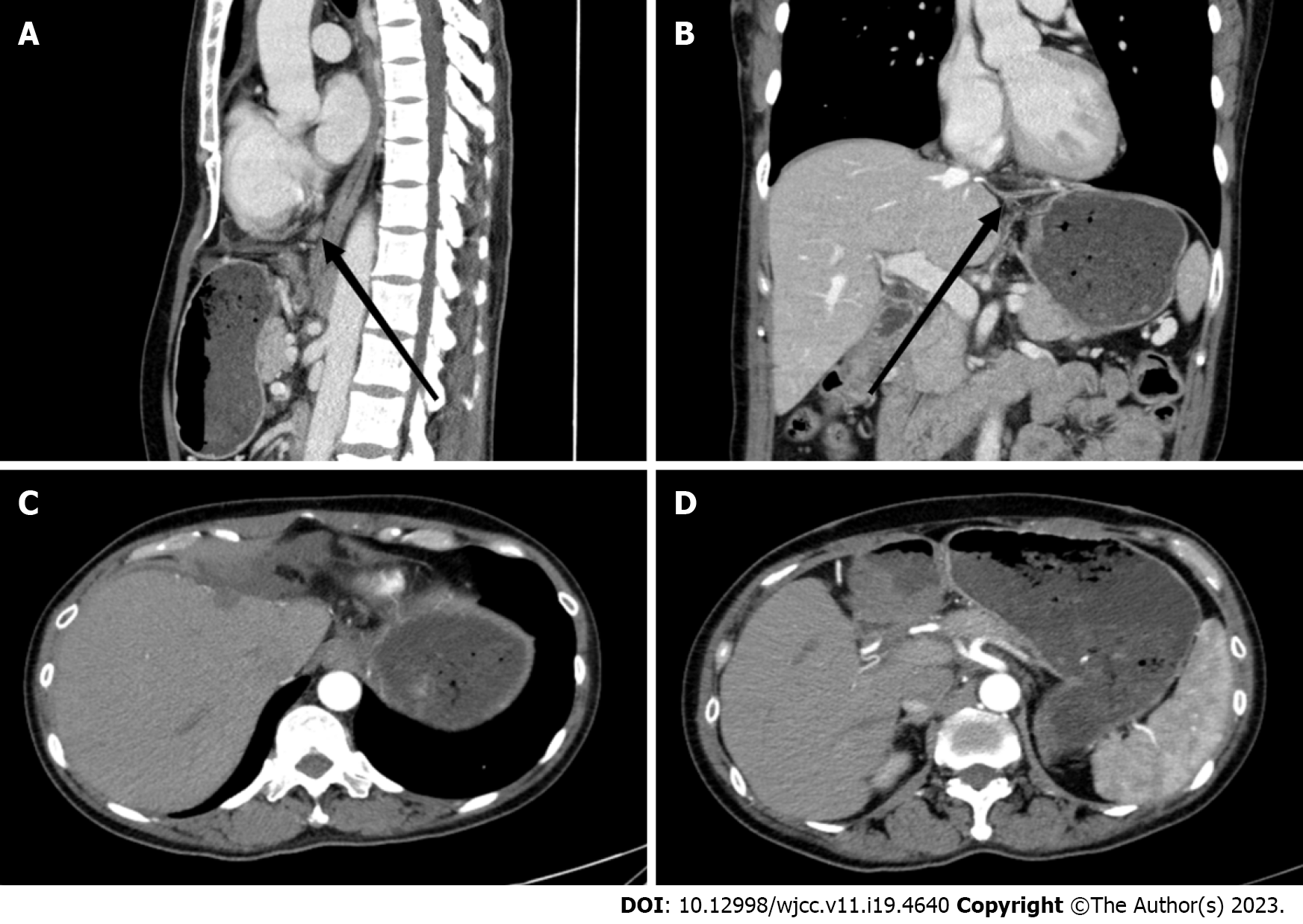

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination of the upper abdomen, the shape and size of the liver were as usual. A mass (Figure 1A-D: Maximum diameter 36 mm × 28 mm) was seen under the capsule of the left inner lobe of the liver, which was moderately and inhomogeneously enhanced, with an enhanced capsule and fusion of two nodules. There were no abnormal signals in the parenchyma of the remaining liver. The portal vein and hepatic vein were patent, and there were no signs of filling defects or obstructions. There were no signs of enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Additionally, there were no signs of effusion in the abdominal cavity. Pharyngorhinoscopy did not reveal any abnormalities in the nasopharynx.

On the basis of her history, signs, imaging findings, and postoperative pathology (Figure 2B-D) and immunohistochemistry, the patient was ultimately diagnosed with lymphoepithelioma-like HCC.

On January 26, 2022, the patient underwent laparoscopic left hepatectomy plus regional lymphadenectomy based on her medical history, signs, and imaging findings. The hepatectomy encompassed the entire left side of the liver; the lymphadenectomy encompassed the lymph nodes anterior and posterior to the common hepatic artery as well as those posterior to the pancreatic head.

After the operation, the patient received symptomatic treatment including immune and targeted therapies (lenvatinib mesilate capsules: 8 mg orally once a day; tislelizumab injection: 200 mg given intravenously every 3 wk), and she recovered uneventfully. After discharge, regular outpatient follow-up and drug treatment were continued. At the last outpatient follow-up on December 30, 2022, computed tomography (CT) examination showed no obvious masses in the operative area and no obvious abnormal lymph nodes in the abdominal cavity or retroperitoneum (Figure 3). Tumour marker levels were also reduced (Figure 4).

LELC is believed to have unique epidemiological and pathological characteristics. The prognosis is good compared to typical HCC and ICC. LELC may be associated with a large lymphocytic infiltrate, which in this unique variant of HCC may be associated with an immune response. Overall, the pathogenesis of LELC and the factors affecting its prognosis deserve further investigation.

In contrast, the patient's serum levels of AFP were unremarkable, and this may help to differentiate LELC from primary liver tumors, such as HCC and ICC. Positron emission tomography/CT is recommended when LELC is suspected to occur in an uncommon site such as the liver.

The clinical presentation and imaging findings of patients with LELC are not specific. Most cases were confirmed by pathological diagnosis and post-surgical immunohistochemistry. The precise diagnosis is made by pathology, and the immunohistochemical findings show numerous large, atypical, poorly differentiated epithelial cells with an eosinophilic cytoplasm and high expression of CK, CK5/6, and P63[12]. Desmin belongs to the intermediate fibronectin family, which connects organelles by forming a cytoskeletal network. During carcinogenesis, an increase in the number of Desmin-positive cells was observed in advanced tumors, consistent with increased angiogenesis and microvascular maturation. Vimentin is among the most common members of mesenchymal cell-specific intermediate filaments. Many proteomic studies have shown that vimentin is a metastasis-associated factor in a variety of malignancies, such as prostate, breast, gastric, and gallbladder cancers. This suggests that vimentin plays an important role in tumor progression and may serve as a potential biomarker of tumor metastasis. The correlation between the expression of vimentin, a canonical marker of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and malignancy has been extensively studied; however, how vimentin regulates tumor metastasis and survival is still under investigation. These features are confirmed in the present case report.

According to an analysis of the current literature, patients with LEL-ICC have a median age of 57 (46–64) years and are mainly Asian women, with 92% of patients overall being Asian[7]. The WHO updated the key histologic feature of LELC in 2019, that is, most areas had more lymphocytes than tumor cells as shown by hematoxylin and eosin staining. Based on this histologic feature, the WHO proposed a new subtype of liver cancer called lymphocyte-enriched HCC[13].

Therefore, pathology is the basic method for the diagnosis of LELC. Microscopically, atypical tumor cells are barely differentiated and have a massive lymphocytic infiltration (Figure 2C). Based on the above pathological features, LELC can be distinguished from typical HCC. In addition, LELC can be divided into two types, namely, LEL-HCC and LEL-ICC, according to microscopic observation and the expression of immunohistochemical factors. However, diagnosis using pathological methods is only used for patients who have undergone hepatectomy, liver puncture, or liver transplantation.

The clinical presentation of patients with LELC is nonspecific. Most patients have physical examination findings, while some patients present with symptoms of right upper abdominal pain or chronic cholecystitis[14-16]. Nonetheless, owing to the lack of specific clinical manifestations, it is difficult to diagnose LELC before surgery.

The diagnosis and treatment strategy for LELC can be summarized as follows. First, since LELC is a relatively rare HCC variant with a low incidence, it cannot be ruled out in the diagnosis and treatment of HCC. In addition, it is recommended that treatment strategies be developed by a multidisciplinary team. Second, it is best to perform a preoperative EBV test; if the result is positive, it will further support the diagnosis of LELC. Compared to patients with EBV-negative LEL-ICC, those with EBV-associated LEL-ICC usually have favourable postsurgical outcomes. Chan et al[17] found distinctively frequent DNA hypermethylation in seven EBV-associated LEL-CC lesions. Other viruses, such as hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus, are not associated with LEL-ICC[18,19]. Third, for advanced liver tumors, a liver biopsy and associated pathological diagnosis are recommended. If LELC is present, it should be treated aggressively. Fourth, when postoperative pathological results indicate the presence of LELC, active intervention and treatment are recommended for long-term survival because, even with local recurrence and metastasis, LELC may have a favourable prognosis. Lymphoepithelioma is a rare cancer originally described in 1982 in the nasopharynx[20]. Since then, cases have been reported in different organs, such as the salivary glands, stomach, lungs, colon, uterus, and ovaries[21], and were designated as LELCs. In 2010, the WHO characterized LELC as undifferentiated cancer cells with markedly infiltrating lymphocytes[22]. The lack of specificity of LELC necessitates a systematic preoperative exa

Herein, a rare case of primary hepatocellular LELC is reported. The patient was followed up for 12 mo after surgery and was treated with regular immunotherapy and targeted therapy. No tumour recurrence was found. This case will further expand our overall knowledge of the diagnosis and treatment of this rare tumor.

Thanks to Dr. He Yongzhu for his guidance on this article.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Elkady N, Egypt; Rizzo A, Italy S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Nieto-Coronel MT, Perez-Sanchez VM, Salazar-Campos JE, Diaz-Molina R, Arce-Salinas CH. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of breast: A case report and review of the literature. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2019;62:125-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sathirareuangchai S, Hirata K. Pulmonary Lymphoepithelioma-like Carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143:1027-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Venyo AK. Primary Lymphoepithelioma-Like Carcinoma of the Prostate Gland: A Review of the Literature. Scientifica (Cairo). 2016;2016:1876218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Raphael V, Jitani AK, Sailo SL, Vakha M. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the urinary bladder: A rare case report. Urol Ann. 2015;7:516-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Makannavar JH, KishanPrasad HL, Shetty JK. Lymphoepithelioma-like Carcinoma of Endometrium; A Rare Case Report. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2015;6:130-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | An SL, Liu LG, Zheng YL, Rong WQ, Wu F, Wang LM, Feng L, Liu FQ, Tian F, Wu JX. Primary lymphoepithelioma-like hepatocellular carcinoma: report of a locally advanced case and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:3282-3287. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Zhang K, Tao C, Tao Z, Wu F, An S, Wu J, Rong W. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma in liver not associated with Epstein-Barr virus: a report of 3 cases and literature review. Diagn Pathol. 2020;15:115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Labgaa I, Stueck A, Ward SC. Lymphoepithelioma-Like Carcinoma in Liver. Am J Pathol. 2017;187:1438-1444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Geneva: WHO Press, 2010. |

| 10. | Verhoeven RJA, Tong S, Mok BW, Liu J, He S, Zong J, Chen Y, Tsao SW, Lung ML, Chen H. Epstein-Barr Virus BART Long Non-coding RNAs Function as Epigenetic Modulators in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jeng YM, Chen CL, Hsu HC. Lymphoepithelioma-like cholangiocarcinoma: an Epstein-Barr virus-associated tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:516-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jiang WY, Wang R, Pan XF, Shen YZ, Chen TX, Yang YH, Shao JC, Zhu L, Han BH, Yang J, Zhao H. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of primary pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:2610-2616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F, Cree IA; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2554] [Cited by in RCA: 2409] [Article Influence: 481.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 14. | Wang JK, Jin YW, Hu HJ, Regmi P, Ma WJ, Yang Q, Liu F, Ran CD, Su F, Zheng EL, Li FY. Lymphoepithelioma-like hepatocellular carcinoma: A case report and brief review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e9416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nemolato S, Fanni D, Naccarato AG, Ravarino A, Bevilacqua G, Faa G. Lymphoepitelioma-like hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report and a review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4694-4696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Filotico M, Moretti V, Floccari F, D'Amuri A. Very Rare Liver Neoplasm: Lymphoepithelioma-Like (LEL) Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Case Rep Pathol. 2018;2018:2651716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chan AW, Tong JH, Sung MY, Lai PB, To KF. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoepithelioma-like cholangiocarcinoma: a rare variant of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with favourable outcome. Histopathology. 2014;65:674-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gearty SV, Al Jurdi A, Pittman ME, Gupta R. An EBV+ lymphoepithelioma-like cholangiocarcinoma in a young woman with chronic hepatitis B. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Solinas A, Calvisi DF. Lessons from rare tumors: hepatic lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3472-3479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Applebaum EL, Mantravadi P, Haas R. Lymphoepithelioma of the nasopharynx. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:510-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND. Editors. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th Edition, World Health Organization. 2010, pp. 417. |

| 22. | Hoxworth JM, Hanks DK, Araoz PA, Elicker BM, Reddy GP, Webb WR, Leung JW, Gotway MB. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung: radiologic features of an uncommon primary pulmonary neoplasm. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:1294-1299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kriegsmann M, Muley T, Harms A, Tavernar L, Goldmann T, Dienemann H, Herpel E, Warth A. Differential diagnostic value of CD5 and CD117 expression in thoracic tumors: a large scale study of 1465 non-small cell lung cancer cases. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Huang CJ, Feng AC, Fang YF, Ku WH, Chu NM, Yu CT, Liu CC, Lee MY, Hsu LH, Tsai SY, Shih CS, Wang CL. Multimodality treatment and long-term follow-up of the primary pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma. Clin Lung Cancer. 2012;13:359-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ho JC, Lam WK, Wong MP, Wong MK, Ooi GC, Ip MS, Chan-Yeung M, Tsang KW. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung: experience with ten cases. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:890-895. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Ho JC, Lam DC, Wong MK, Lam B, Ip MS, Lam WK. Capecitabine as salvage treatment for lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of lung. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1174-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Guo J, Wang S, Han Y, Jia Z, Wang R. Effects of transarterial chemoembolization on the immunological function of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2021;22:554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Lee MS, Ryoo BY, Hsu CH, Numata K, Stein S, Verret W, Hack SP, Spahn J, Liu B, Abdullah H, Wang Y, He AR, Lee KH; GO30140 investigators. Atezolizumab with or without bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (GO30140): an open-label, multicentre, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:808-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 409] [Article Influence: 81.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sidali S, Trépo E, Sutter O, Nault JC. New concepts in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. United European Gastroenterol J. 2022;10:765-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, Ferrer-Fàbrega J, Burrel M, Garcia-Criado Á, Kelley RK, Galle PR, Mazzaferro V, Salem R, Sangro B, Singal AG, Vogel A, Fuster J, Ayuso C, Bruix J. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J Hepatol. 2022;76:681-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1904] [Cited by in RCA: 2552] [Article Influence: 850.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (59)] |

| 31. | Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, Kudo M, Breder V, Merle P, Kaseb AO, Li D, Verret W, Xu DZ, Hernandez S, Liu J, Huang C, Mulla S, Wang Y, Lim HY, Zhu AX, Cheng AL; IMbrave150 Investigators. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894-1905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2542] [Cited by in RCA: 4645] [Article Influence: 929.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |