Published online Jun 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i17.4084

Peer-review started: February 8, 2023

First decision: March 24, 2023

Revised: April 18, 2023

Accepted: May 19, 2023

Article in press: May 19, 2023

Published online: June 16, 2023

Processing time: 124 Days and 0.8 Hours

Primary pelvic Echinococcus granulosus infection is clinically rare. The reported cases of pelvic Echinococcus granulosus infection are considered to be secondary to cystic echinococcosis in other organs. Single Echinococcus granulosus infection is very rare.

In this report, we presented a case of primary pelvic Echinococcus granulosus infection admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University. We described the key diagnostic points and surgical treatment of this case. We also summarized the epidemiological characteristics and pathogenesis of the disease.

Our case may provide clinical data for the diagnosis and treatment of primary pelvic Echinococcus granulosus infection.

Core Tip: Primary pelvic Echinococcus granulosus infection is clinically rare. In this report, we presented a case of primary pelvic Echinococcus granulosus infection. We described the key diagnostic points and surgical treatment of this case and summarized the epidemiological characteristics and pathogenesis of the disease. Our case may provide clinical data for the diagnosis and treatment of primary pelvic Echinococcus granulosus infection.

- Citation: Abulaiti Y, Kadi A, Tayier B, Tuergan T, Shalayiadang P, Abulizi A, Ahan A. Primary pelvic Echinococcus granulosus infection: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(17): 4084-4089

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i17/4084.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i17.4084

Echinococcosis, also known as hydatidosis, is a zoonotic disease caused by infection with echinococcus, which includes Echinococcus granulosus, Echinococcus multilocularis, Echinococcus oligarthrus, and Echinococcus vogeli[1]. Echinococcus cyst matures in the small intestine of dogs or other canines and grows and reproduces in internal organs of ungulates (sheep, cattle, and pigs). Humans are the accidental intermediate hosts of echinococcus[2]. So far, the human-to-human transmission of echinococcus has not been reported. The most common parasitic sites of echinococcus are the liver (68%-75%) and lung (15%-22%)[3]. Infection of echinococcus in other parts of the body, such as the spleen, kidneys, heart, bones, muscles, skin, abdomen or pelvis, brain, and ovaries, accounts for 5%-10%[4]. Hydatidosis is common in regions of agriculture and animal husbandry, such as the Mediterranean region, the southwestern United States, Latin America, the Middle East, China, and Africa[5].

A 70-year-old male was admitted due to pelvic mass found on physical examination for more than 1 mo.

He had no complaint of discomfort, and had normal urination and defecation, and normal diet.

The patient had no history of alcohol consumption, drug abuse or other high-risk behaviors causing pelvic Echinococcus granulosus infection. He was in good health and denied any history of hypertension, diabetes and/or heart diseases.

The patient was from a village in Hutubi County, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, and had a history of dog exposure.

On abdominal examination, a bulge in the lower abdomen was observed.

Carbohydrate antigen antigen 125 was 27.50 U/mL. The remaining indicators of laboratory analysis were within the normal range, such as white blood cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, alpha-fetoprotein, Carbohydrate antigen 199, carcinoembryonic antigen, etc.

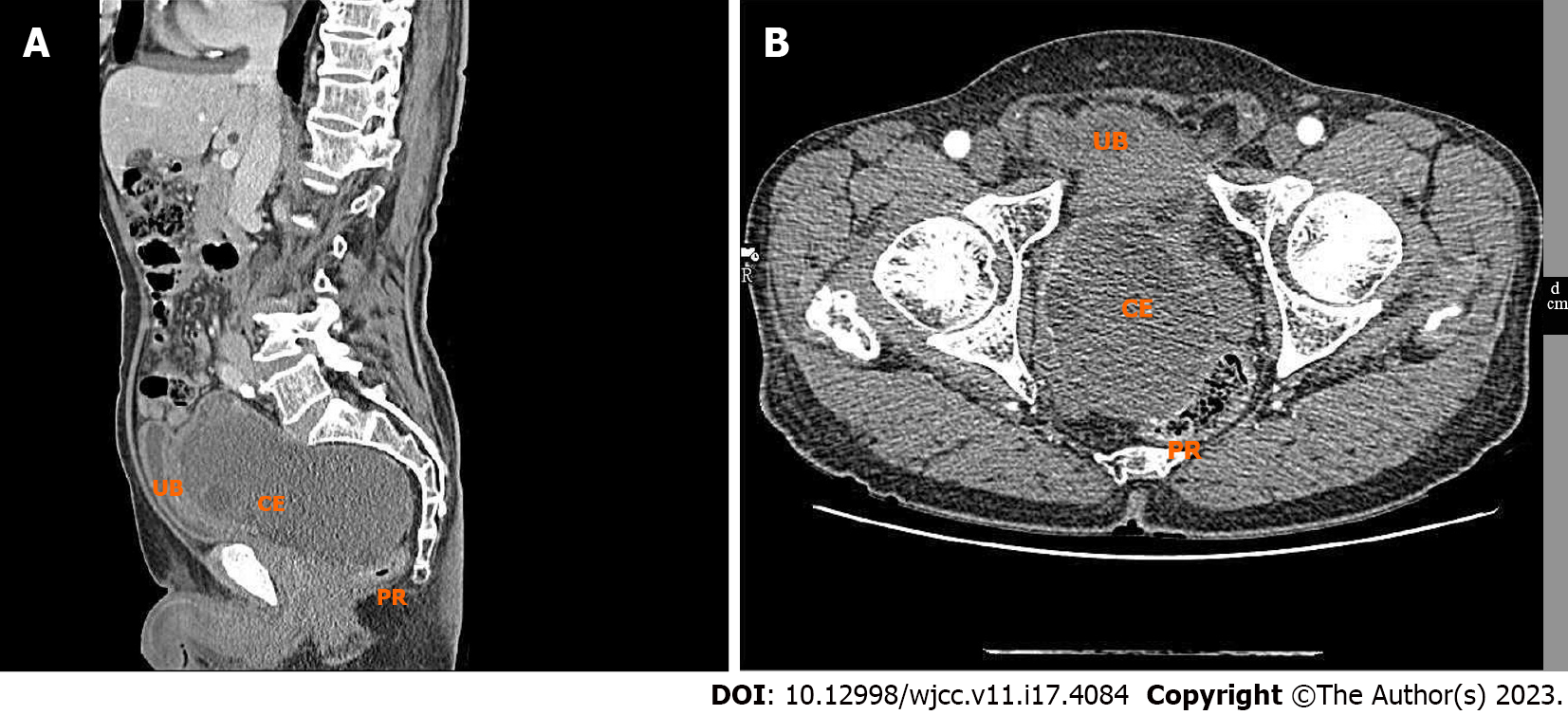

Thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic enhanced computed tomography (CT) scans showed a space-occupying lesion with mixed density in the vesicorectal space, which was considered as a benign lesion and was more likely to be hydatid disease. No lesion was observed in the liver, spleen, chest and lungs. Ultrasound showed a mixed pelvic mass measuring 14.88 cm × 8.71 cm (Figure 1).

Primary pelvic echinococcus infection was diagnosed according to imaging examination and medical history.

Surgical treatment was planned after preoperative preparation. Intraoperatively, it was observed that the mass extended from the bottom of the pelvis to vesicorectal space, with a calcified outer wall and a hard texture with high-tension. The back of the mass was densely adhered to the lower end of the rectum. The needle puncture and pathological examination of the mass was firstly performed after isolating the mass from the surrounding tissues using hypertonic saline. There is no obvious bleeding during needle puncture for mass. Then, after opening the outer wall of mass (measuring 15 mm in thickness), a large number of necrotic hydatid ascosycetes were observed. Cyst puncture decompression was performed and a large number of pale yellow cysts were sucked out, considered as Echinococcus granulosus. The total capacity of the cyst was about 2500 mL. The cyst outer wall and the surface nodules of outer wall were sent for rapid pathological examination, which suggested hydatidosis. There were chronic inflammatory changes in the surface nodules of outer wall, indicating hydatid fibrous outer capsule. Therefore, the intraoperative diagnosis was suggested as pelvic echinococcus. The inner capsule and the dissociative outer capsule of the echinococcus cyst was completely removed. However, the outer capsules that were densely adherent to the anterior rectal wall and pelvic floor were not resected. Postoperative routine pathological evaluation confirmed pelvic Echinococcosis granulosis (Figure 2).

After surgery, the patient's condition was improved. There was small amount of reddish fluid in the pelvic drainage fluid, and the drainage tube was removed on the sixth day after surgery. Subsequently, the patient was discharged. The patient was followed up for one year after surgery, and no recurrence was found.

Echinococcosis is a zoonotic parasitic disease. Echinococcus granulosus, a causative pathogen of cystic echinococcosis, and, Echinococcus multilocularis, a causative pathogen of alveolar echinococcosis, have important clinical significance[6]. These diseases have been found in Inner Mongolia, Sichuan, Tibet Autonomous Region, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, Yunnan, Shaanxi, and Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in China[7]. Echinococcus infection in humans may be via contact with egg-containing filth. The oncosphere hatches in the human intestine and then spreads to other organs via blood circulation. The liver is the most commonly affected organ, followed by the lungs. Although infection of any organ can occur, primary pelvic infection is very rare, accounting for 0.2%-2% of all cases[8]. In 80% of cases with pelvic hydatid disease, the ovary is the most commonly affected organ, followed by the uterus[9]. Interestingly, in the case of this study, only the pelvic cavity was involved, but not other organs. Most studies have shown multiple organ involvement. However, rare organ involvement is usually associated with common organ involvement. In our case, however, this association was not observed. The case in this study was with primary solitary pelvic hydatid disease, and the lesions were closely related to the rectum and bladder. The infection source may be that the oncosphere hatches in the gastroduodenal, enters the pelvic cavity through the pelvic venous plexus and peri-bladder tissues, and then develops into a solitary cyst[10]. Echinococcus granulosus may compress infected and adjacent tissues and can also secrete toxins[11]. Primary pelvic hydatid disease has no specific clinical symptoms, and are usually found on physical examination or by local compression symptoms resulting from enlarging cyst, such as compression of the bladder or rectum, urinary catheter blockage, kidney failure, lower abdominal pain, etc[12]. After reaching the tissue or organ, hydatid cysts grow about 1 cm per year, which explains why most patients remain asymptomatic for years. A small number of cases may present with signs and symptoms, depending on the size, number, and location of lesions, their relationship to vascular structures, and compression of adjacent organs. In areas where this zoonotic disease is endemic, it should be considered a differential diagnosis option for pelvic tumors. Pelvic hydatid disease may resemble malignancy[13]. Hydatid disease is mostly diagnosed based on clinical presentation, serology, and imaging (CT scan or ultrasound scan) findings. The CT scan could show calcifications and cysts of hydatid disease[14]. Although the tests mentioned above are highly sensitive, the gold standard is histopathology, and surgery has always been considered the primary treatment choice[5]. During surgery, the risk of cyst leakage, severe allergic symptoms, rectal damage, and intestinal fistula due to complete capsule peeling should be avoided. The outer capsule should be peeled off as much as possible, while for those that cannot be peeled off and removed, concentrated sodium should be used for repeated rinsing. Cystic collapse, calcification, or no cystic lesions are used as the efficacy evaluation criterion for the clinical recovery of patients. Patients who develop new cysts of the same size or larger than previous cysts in the same or different organs after treatment are considered disease recurrence. However, the recurrence rate after surgery for primary echinococcosis ranges from 8% to 22%, and most recurrences occur within two years after surgery[15]. Mebendazole or albendazole should be used as an adjuvant to surgery if resection is incomplete. Surgery is the most acceptable treatment for pelvic echinococcosis, while albendazole therapy is effective in cases with small cysts or patients who are unsuitable for surgery. In general, albendazole is not suitable for all cases. Preoperative albendazole treatment can reduce intracapsular pressure, while postoperative albendazole can decrease the risk of echinococcosis recurrence. Preoperative and postoperative albendazole is the optimal treatment option[16]. Percutaneous suction, injection, and aspiration are effective and safe treatments for hepatic hydatid disease. Previously, direct puncture of echinococcosis was considered unsafe because there was a risk of allergic reactions and wider spreading if the cyst fluid was spilled into the peritoneal cavity. Due to the complex anatomy of the pelvis and the potential risk of urogenital injury, treating pelvic hydatid disease using percutaneous suction, injection, and aspiration can be technically challenging. However, this technique is only suitable for pelvic hydatids if there is a safe route of needle penetration into the cyst confirmed by imaging[17].

Primary pelvic hydatidosis is rare even in endemic areas. Therefore, it is important to distinguish pelvic hydatidosis from other cystic lesions that occur in the pelvis, especially in endemic areas. Although pelvic hydatidosis is not malignant, it is a serious condition that should be distinguished from those with a poor prognosis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Amante MF, Argentina; Brusciano L, Italy S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Başgül A, Kavak ZN, Gökaslan H, Küllü S. Hydatid cyst of the uterus. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2002;10:67-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kamali M, Yousefi F, Mohammadi M, Alavi S, Salmanzadeh S, Geravandi S, Kamali A. Hydatid Cyst Epidemiology in Khuzestan, Iran: A 15-year Evaluation. Arch Clin Infect Dis. 2018;13:e13765. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Agudelo Higuita NI, Brunetti E, McCloskey C. Cystic Echinococcosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:518-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 31.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Geramizadeh B. Isolated Peritoneal, Mesenteric, and Omental Hydatid Cyst: A Clinicopathologic Narrative Review. Iran J Med Sci. 2017;42:517-523. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Abdelmaksoud MM, Jamjoom A, Hafez MT. Simultaneous Huge Splenic and Mesenteric Hydatid Cyst. Case Rep Surg. 2020;2020:7050174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Taxy JB, Gibson WE, Kaufman MW. Echinococcosis: Unexpected Occurrence and the Diagnostic Contribution of Routine Histopathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:94-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. |

Wu W, Hu W, Qian W. A nationwide sampling survey on echinococcosis in China during 2012-2016.

|

| 8. | Gautam S, Patil PL, Sharma R, Darbari A. Simultaneous multiple organ involvement with hydatid cyst: left lung, liver and pelvic cavity. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sarkar S, Sanyal P, Das MK, Kumar S, Panja S. Acute Urinary Retention due to Primary Pelvic Hydatid Cyst: A Rare Case Report and Literature Review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:PD06-PD08. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Houcem H, Yassine O, Aziz K, Zied M, Beya C, Yassine N. A rare case of acute urinary retention in a woman caused by primary retro vesical hydatid cyst. Urol Case Rep. 2021;36:101589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Feng P, Yang J, Tang M, Zhao K, Li K. Preliminary efficacy of laparoscopy combined with choledochoscopy in the treatment of hepatic hydatid disease. Journal of Practical Hepatology. 2018;21:135-136. |

| 12. | Sen P, Demirdal T, Nemli SA. Evaluation of clinical, diagnostic and treatment aspects in hydatid disease: analysis of an 8-year experience. Afr Health Sci. 2019;19:2431-2438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Aybatlı A, Kaplan PB, Yüce MA, Yalçın O. Huge solitary primary pelvic hydatid cyst presenting as an ovarian malignancy: case report. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2009;10:181-183. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Singh B. Mesenteric Hydatid Cyst. Nepalese Journal of Radiology 2018; 8: 43-46. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Gamoudi A, Ben Romdhane K, Farhat K, Khattech R, Hechiche M, Rahal K. [Ovarian hydatic cyst. 7 cases]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 1995;24:144-148. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Ghafouri M, Khorasani EY, Shokri A. Primary pelvic hydatid cyst in an infertile female, A case report. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:1769-1773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Khuroo MS. Percutaneous Drainage in Hepatic Hydatidosis-The PAIR Technique: Concept, Technique, and Results. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2021;11:592-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |