Published online Jan 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i1.242

Peer-review started: October 27, 2022

First decision: November 11, 2022

Revised: November 23, 2022

Accepted: December 15, 2022

Article in press: December 15, 2022

Published online: January 6, 2023

Processing time: 67 Days and 23.3 Hours

Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm is a condition rarely encountered by clinicians; this, its etiology and presentation as well as appropriate treatments are not well studied. Although it is treated by removal of the diseased gallbladder and cystic artery, such surgery can be difficult and risky if acute inflammation with bleeding occurs, and not every patient can tolerate the surgery.

An 81-year-old man complained of epigastric pain and tarry stool passage that lasted for 3 d. He had a medical history of poor cardiopulmonary function. The computed tomographic scan of abdomen showed cystic artery pseudoaneurysm and dilatation of gallbladder. Because of high adverse outcomes related to general anesthesia, the patient was successfully managed with endovascular embolization for this cystic artery pseudoaneurysm and percutaneous drainage for the dis

A patient with cystic artery pseudoaneurysm may quickly deteriorate with the occurrence of concurrent arterial bleeding and sepsis. This report presents the case of a patient who did not undergo surgery due to multiple cardiopulmonary com

Core Tip: Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm is a condition rarely encountered by clinicians. A patient’s condition may quickly deteriorate with the occurrence of concurrent arterial bleeding and sepsis. Although it is treated by removal of the diseased gallbladder and cystic artery, such surgery can be difficult and risky if acute inflammation with bleeding occurs, and not every patient can tolerate the surgery. Endovascular embolization and biliary drainage may provide an alternative option to manage this complicated condition.

- Citation: Liu YL, Hsieh CT, Yeh YJ, Liu H. Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(1): 242-248

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i1/242.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i1.242

Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm is a rare condition with few cases reported in the literature[1]. The pre

An 81-year-old man presented to the emergency department complaining of epigastric pain and tarry stool passage that lasted for 3 d.

Of 3 d prior to admission, the patient developed epigastric pain and tarry stool passage. Because of progressive symptoms, he was brought to the emergency department of our hospital.

Prior to this incident, he was admitted to the hospital three times in 6 mo due to acute cardiopulmonary distress. The first admission was for lung fibrosis exacerbated by pneumonia, pleural effusion, and congestive heart failure, with an ejection fraction of 25%; the second admission occurred 2 mo later for pulmonary edema; and the third admission occurred in the following month as a result of coronary artery disease (CAD) accompanied by cardiogenic shock and acute pulmonary congestion. His CAD was treated using percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty with the initiation of antiplatelet therapy.

No remarkable history.

The patient presented with slight hypotension without tachycardia or fever (blood pressure, 92/60 mmHg; pulse rate, 62 bpm; body temperature, 36.9 °C). The patient appeared mild confused with limited activity due to general weakness. Mild abdominal distension with poor appetite was complained, but no dizziness, shortness of breath, chest tightness, abdominal pain or decreased urine amount was noticed. Further physical examination revealed a soft abdomen without obvious point tenderness, muscle guarding or rebounding pain. He was not pale nor icteric.

Laboratory tests indicated leukocytosis with left shift (white blood cell count, 10600/μL; segment, 73.3%), direct bilirubinemia (direct bilirubin, 0.7 mg/dL; total bilirubin, 1.6 mg/dL) and elevated liver enzyme levels (alanine aminotransferase, 648 IU/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 130 IU/L); anemia, thrombocytopenia, renal insufficiency, and electrolyte imbalance were not detected. Virology tests also confirmed the absence of hepatitis B or C viral infection.

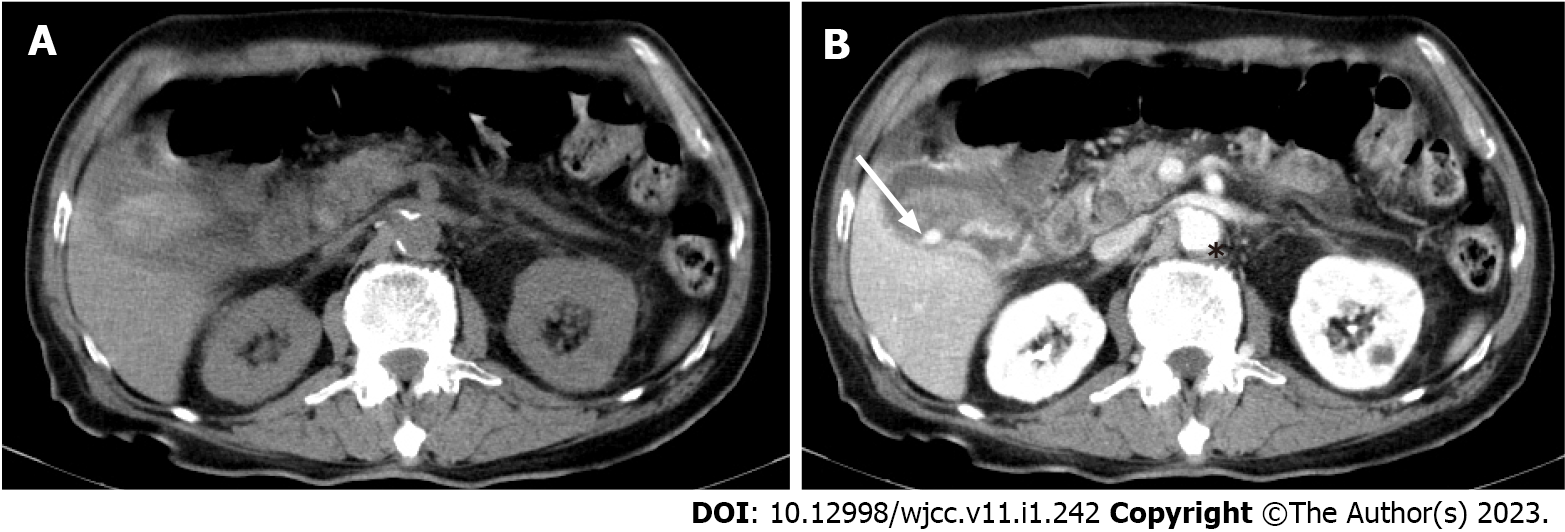

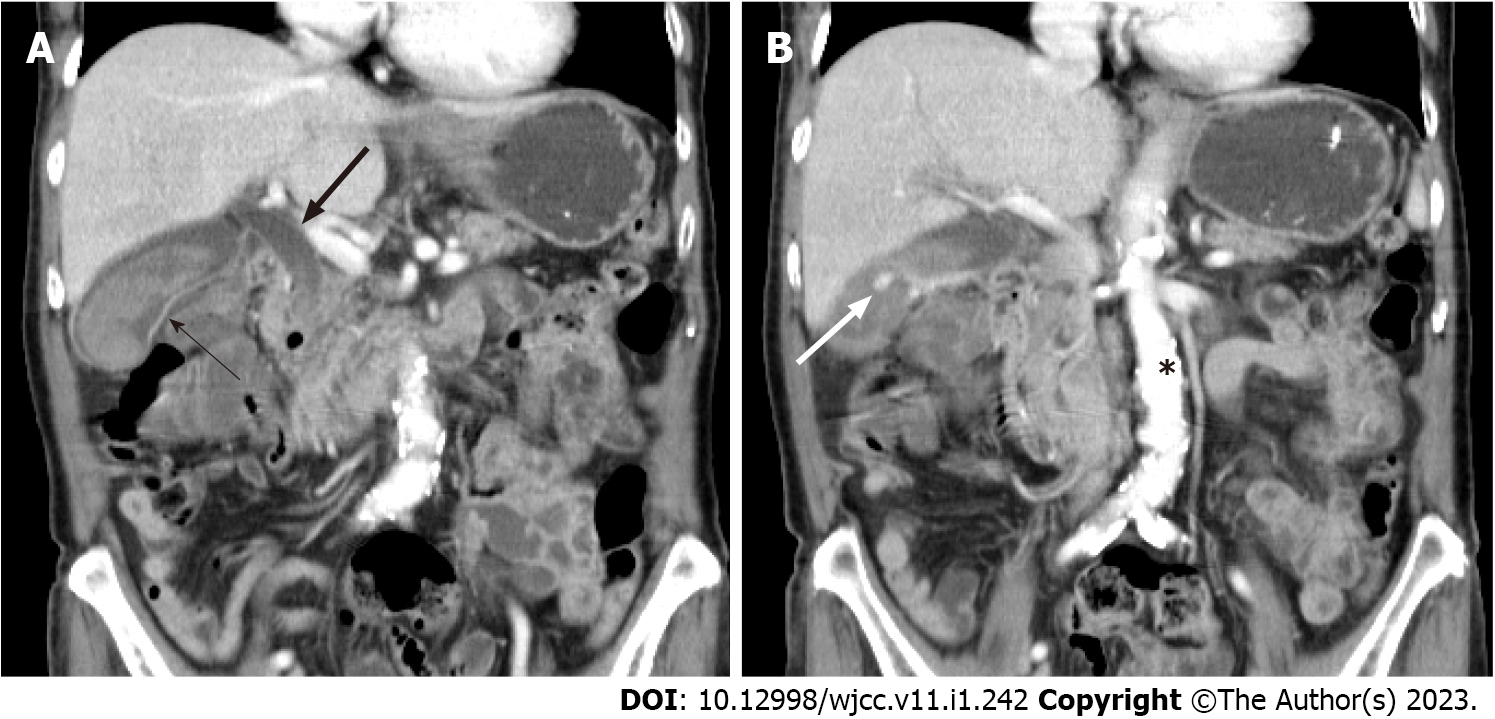

The patient was then admitted to a gastroenterology ward owing to suspicion of cholecystitis and upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Abdominal ultrasound revealed the presence of gallbladder sludge. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast was performed the next afternoon; the scan revealed an enhancing pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery with high-density material in the gallbladder and common bile duct (CBD) and mild dilatation of the bilateral intrahepatic duct (IHD) and CBD (Figures 1 and 2).

Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm.

The general surgery department was consulted for surgical intervention, but biliary drainage was advised due to the high risk of adverse outcomes related to general anesthesia and complications associated with acute inflammation. The following morning, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) did not reveal any active bleeding, although reflux esophagitis (Los Angeles Classification System Grade A) and erythematous gastritis were observed. The duodenum was examined to the 2nd portion, and no bleeder or blood clot was identified. The laboratory data indicated ongoing hepatitis and biliary obstruction (alanine aminotransferase, 632 IU/dL; aspartate aminotransferase, 118 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase, 400 IU/L; gamma-glutamyl transferase, 632 IU/L; total bilirubin, 2.0 mg/dL); thus, percutaneous transhepatic bile duct drainage (PTCD) was scheduled for that afternoon, and a 10-French drainage catheter was placed in the CBD through the right IHD. Bloody discharge from the PTCD drainage tube was observed, and thus, TAE was considered for cystic artery embolization but deferred due to the risk of gallbladder ischemia (which was highlighted during a multidisciplinary discussion).

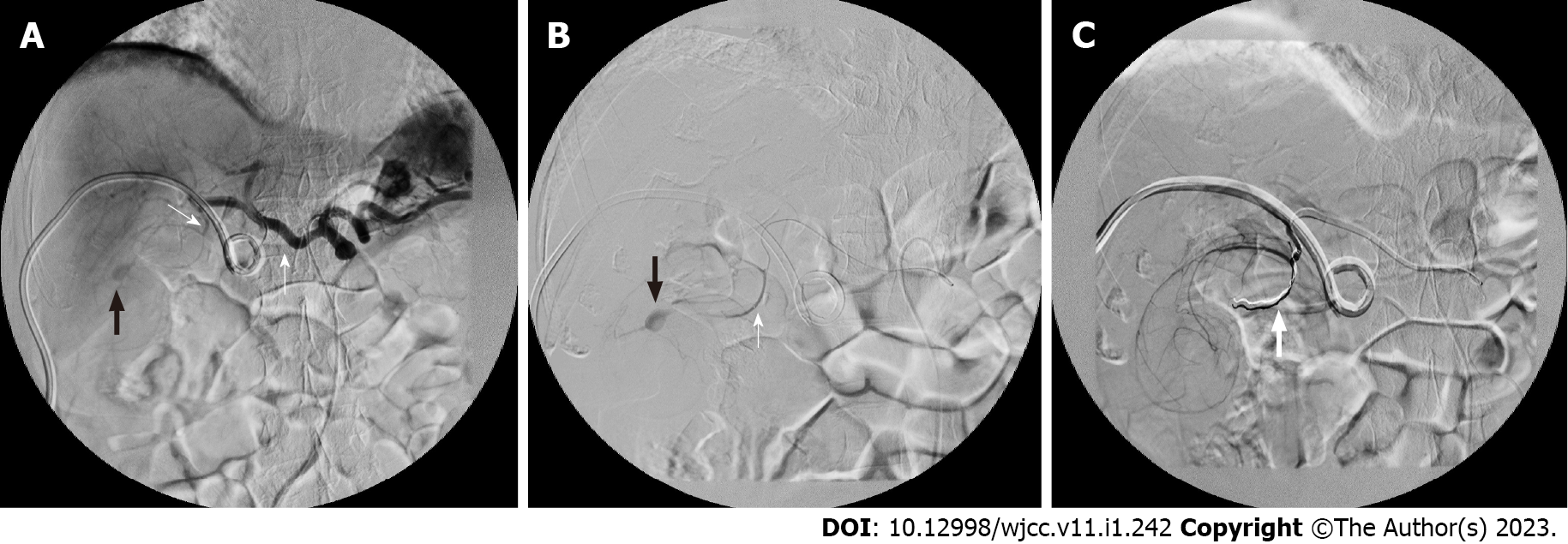

Two days after patient admission, massive haemobilia was observed from the PTCD drainage tube, and it was accompanied by a decreased hematocrit level [from 14.0 (at the emergency room) to 9.1 g/dL]. The general surgeon, who was consulted again, suggested aggressive resuscitation with TAE for suspected cystic artery-pseudoaneurysm rupture. Prompt embolization was arranged. The celiac and cystic artery were accessed from the right common femoral artery with Cordis RC1 and asahi soft microcatheter. Embolization was done to a branch of the cystic artery as distal as possible with 0.018 cm-3 cm and 2 mm-5 cm coils (Figures 3A and 3B). No further opacification of the bleeding vessel was observed from follow-up arteriography (Figure 3C). Several hours after endovascular embolization, the patient presented with severe right upper-quadrant tenderness with profound leukocytosis (white cell counts, 32000/μ). Progression of cholecystitis was suspected, and thus, CT-guided percutaneous gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) was performed 10 h after TAE. A CT scan revealed a distended gallbladder with heterogeneous contents, and an 8-French drainage catheter was placed inside the gallbladder. The patient continued to receive antibiotic treatment for Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia and was discharged 10 d after TAE. His PTCD and PTGBD were removed 15 d and 28 d after insertion, respectively; the removal procedures were performed when the patient was in stable condition and after normalized laboratory test results were obtained (white blood cell count, 5800/μ; total bilirubin, 0.9 mg/dL; alanine aminotransferase, 28 IU/L).

During the last follow-up session prior to the completion of this case report, the patient was in a stable condition without further signs of cholecystitis or haemobilia.

Although the pathogenesis of pseudoaneurysm is well established in other named vessels[3], its occurrence in the cystic artery is not well understood; few cases have been documented[1], and even fewer have been associated with upper gastrointestinal bleeding[4]. Pseudoaneurysm can result from any stimulus that damages the elastic and muscular layer of the arterial wall[5]; reported etiologies of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm are used to categorize the condition into traumatic, inflammatory, or idiopathic pseudoaneurysms[3]. Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm may be associated with biliary surgery, and recently, it has been associated with other invasive liver and biliary procedures[1,6]; its incidence has increased with the increased prevalence of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and invasive interventions[5]; the related injuries may be caused by the excessive use of electrocautery at the infundibulum of the gallbladder, bile leakage, presence of a nearby metallic clip, or iatrogenic trauma[6,7]. Most of the other reported precholecystectomy cases involved local inflammation such as cholecystitis or pancreatitis[5]. Pancreatitis was reported as the cause of cystic artery pseudoaneurysms in one case report[8]; however, more often than not, pancreatitis contributes to pseudoaneurysms located at the pancreaticoduodenal arcade or splenic artery[5]. Cholecystitis is the predominant cause of cystic artery pseudoaneurysms. A commonly accepted theory is that the erosion of the cystic arterial wall due to inflammation leads to adventitial damage and thrombosis of the vasa vasorum, which eventually corrupt the muscular and elastic components of the media and intima and lead to the development of pseudoaneurysm with arterial extravasation[4,9]. The erosion of the cystic artery by a large gallstone was proposed in one case report[10].

Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm can be challenging to diagnose upon presentation. In the early stages, the patient may experience nausea, vomiting, and vague abdominal pain[11]. The classic presentation of haemobilia is known as Quincke’s triad[12], which can also be observed in cases of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm with the variable occurrence of upper abdominal pain (70%), jaundice (60%), and gastrointestinal hemorrhage (45%), with 32%-40% of patients presenting with all three symptoms[9,13]. The incidences of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm and its sequelae are disproportionally low relative to the high incidence of cholecystitis; an explanation is that adjacent inflammation usually causes thrombus formation, leading to the early thrombosis of a newly formed pseudoaneurysm[14]. Patient factors such as the presence of atherosclerosis, hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, or vasculitis may also contribute to pseudoaneurysm formation[9]. This finding is consistent with the observation that most reported cases involve older patients, with a recent literature review of 50 reported cases of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm revealing that the median age at diagnosis was 68 years[1]. Gastrointestinal bleeding may be obscured by the intact sphincter of Oddi[15], which was observed in our patient with a negative EGD examination and in two other case reports in which haemobilia-induced blood clots on the duodenal wall were erroneously identified as atypical ulcers[5,9]. A hemorrhage can be massive when it occurs concurrently with enterobiliary fistula caused by chronic inflammation; this situation was observed in cases involving xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis[16], cholecysto-jejunal fistula[9], and severe rectal bleeding secondary to cholecystocolic fistula[17]. The literature review by Fujimoto et al[1] included 51 reported cases since 1976, which is one of the most complete reviews to date. According to their review, cystic artery pseudoaneurysm was almost always involved with cholecystitis, and gallstones were found in 91% of patients; gallbladder rupture was common (83%), and intraperitoneal bleeding was reported in 18%. More than half reported cases received TAE, and 48% of those patients did not receive concurrent cholecystectomy.

A case series by Akatsu et al[13] indicated that 58% of pseudoaneurysms are located in the gallbladder, where they range from 0.2 cm to 4 cm in length, although pseudoaneurysms measuring up to 5 cm have been reported[6]. The safest and most convenient diagnostic tool for cystic artery pseudoaneurysm in an acute setting is abdominal ultrasound, which provides the additional benefit of dynamic imaging. On Doppler imaging, a typical yin-yang symbol (i.e., swirling flow)[3] or an anechoic lesion with color flow[9] may be observed. Unfortunately, low sensitivity has been reported with ultrasound (27% detection rate in one series[9]), particularly for smaller lesions, and pseudoaneurysms can be obscured by the acoustic shadowing of the gallbladder calculi. Contrast-enhanced CT provides more information, often displaying a pseudoaneurysm as a high attenuation nodule[1,3], which can sometimes mimic gallstones[3,4]; in cases involving concurrent intracholecystic hemorrhage, heterogeneous high attenuation may also be observed in the gallbladder[1,9]. CTA can further delineate the vasculature of a target lesion[2,3] and aid percutaneous treatment planning[17]; however, it lacks the dynamic imaging features provided by Doppler ultrasound and angiography[3], which allow for pulsatile masses be observed[18]. Angiography is sometimes regarded as the gold standard for diagnosing cystic artery pseudoaneurysm because it has a sensitivity of 80% and the ability to detect lesions of < 10 mm in size[9]; although it is mostly invasive, it can provide therapeutic effects when combined with interventional embolization, either as a definitive treatment or for the purpose of bridging to cholecystectomy[3].

The mortality rate of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm can be as high as 50% due primarily to severe complications involving of hemorrhagic shock[19]. The goal of treating patients with cystic artery pseudoaneurysm is to reduce the risk of rupture and hemorrhage[3]. Because of its rare occurrence, the protocol for managing cystic artery pseudoaneurysm has not yet been standardized. However, successful treatments have been reported; they mostly involve embolization at diagnosis followed by staged cholecystectomy with the removal of the pseudoaneurysm or biliary drainage. Embolization is the preferred treatment in an unstable patient with bleeding from a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm[2] because it has a high likelihood of achieving hemostasis and the total obliteration of the aneurysm; emergent surgery in this situation may be ineffective due to the difficulty of identifying the cystic artery with ongoing inflammation and bleeding[5]. As sudden loss of surrounding fluid tension may lead to the rupturing of a previously intact pseudoaneurysm; therefore, embolization should be performed prior to pericholic fluid drainage[18]. Postembolization gallbladder ischemia may be a concern, although no related complications were reported in two case series[8,20]; therefore, this strategy can be applied for patients who may not be able to further surgery. The gallbladder may have retained its perfusion with collateral blood supply from the epicholedochal artery[8].

Our patient did not undergo cholecystectomy after embolization due to the presence of multiple cardiopulmonary comorbidities. Hall et al[4] described a similar case involving an 88-year-old man with ruptured cholecystitis. The patient, whose pseudoaneurysm was initially misinterpreted as a calculus, developed melena and anemia after blood-stained biliary aspiration; his cystic artery was embolized with a mixture of cyanoacrylate and lipiodol, and he recovered well with the removal of his biliary drainage 1 wk later. A follow-up ultrasound revealed a regression of liver abscess and collapsed gallbladder with retained calculi. Our report highlights the importance of early recognition of this rare disease, as it can be associated with substantial bleeding and rapid deterioration, and that prompt, sequential non-surgical intervention can be successful in a patient who cannot withstand emergent operation.

Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm should be suspected in a patient presenting with signs of both cholecystitis and gastrointestinal bleeding. Diagnoses can be made with assistance from colored Doppler imaging and contrast-enhanced CT, but angiography is still the preferred method, particularly for an unstable patient, because it provides accurate imaging of the target lesion and increases the likelihood of immediate intervention. The appropriate treatment includes embolization in an acute setting with staged cholecystectomy; for patients who cannot tolerate surgery, excellent results can also be achieved from performing embolization followed by biliary drainage.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kang LM, China; Yao J, China S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Fujimoto Y, Tomimaru Y, Hatano H, Noguchi K, Nagase H, Hamabe A, Hirota M, Oshima K, Tanida T, Morita S, Imamura H, Iwazawa T, Akagi K, Dono K. Ruptured Cystic Artery Pseudoaneurysm Successfully Treated with Urgent Cholecystectomy: A Case Report and Literature Review. Am J Case Rep. 2018;19:187-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lin CJ, Lee RC, Chiang JH, Wang KL. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery in acalculous cholecystitis successfully treated by transcatheter arterial embolization: A case report. Chin J Radiol. 2007;32:41-44. |

| 3. | Chong JJ, O'Connell T, Munk PL, Yang N, Harris AC. Case of the month #176: pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2012;63:153-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hall TC, Sprenger De Rover W, Habib S, Kumaran M. Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to acute cholecystitis: an unusual cause for haemobilia. BJR Case Rep. 2016;2:20150423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Delgadillo X, Berney T, de Perrot M, Didier D, Morel P. Successful treatment of a pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery with microcoil embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:789-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Proença AL, Veloso Gomes F, Costa N, Bilhim T, Luz JH, Coimbra É. Transarterial Embolization of Iatrogenic Cystic Artery Pseudoaneurysm. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2020;27:115-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | De Molla Neto OL, Ribeiro MA, Saad WA. Pseudoaneurysm of cystic artery after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2006;8:318-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kulkarni V, Deshmukh H, Gupta R. Pseudoaneurysm of anomalous cystic artery due to calculous cholecystitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Glaysher MA, Cruttenden-Wood D, Szentpali K. A rare cause of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage: Ruptured cystic artery pseudoaneurysm with concurrent cholecystojejunal fistula. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Saluja SS, Ray S, Gulati MS, Pal S, Sahni P, Chattopadhyay TK. Acute cholecystitis with massive upper gastrointestinal bleed: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kuzman MS, Adiamah A, Higashi Y, Gomez D. Rare case of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nakajima M, Hoshino H, Hayashi E, Nagano K, Nishimura D, Katada N, Sano H, Okamoto K, Kato K. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery associated with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:750-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Akatsu T, Tanabe M, Shimizu T, Handa K, Kawachi S, Aiura K, Ueda M, Shimazu M, Kitajima M. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery secondary to cholecystitis as a cause of hemobilia: report of a case. Surg Today. 2007;37:412-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Barba CA, Bret PM, Hinchey EJ. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery: a rare cause of hemobilia. Can J Surg. 1994;37:64-66. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Kaman L, Kumar S, Behera A, Katariya RN. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery: a rare cause of hemobilia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1535-1537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Muñoz-Villafranca C, García-Kamirruaga Í, Góme-García P, Atín-del-Campo V, Bárcena-Robredo V, Aguinaga-Alesanco A, Calderón-García Á. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery: An uncommon cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a case of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:375-376. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Carey F, Rault M, Crawford M, Lewis M, Tan K. Case report: cystic artery pseudoaneurysm presenting as a massive per rectum bleed treated with percutaneous coil embolization. CVIR Endovasc. 2020;3:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nkwam N, Heppenstall K. Unruptured Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery associated with acute calculus cholecystitis. J Surg Case Rep. 2010;2010:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sibulesky L, Ridlen M, Pricolo VE. Hemobilia due to cystic artery pseudoaneurysm. Am J Surg. 2006;191:797-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mullen R, Suttie SA, Bhat R, Evgenikos N, Yalamarthi S, McBride KD. Microcoil embolisation of mycotic cystic artery pseudoaneurysm: a viable option in high-risk patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32:1275-1279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |