Published online Feb 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i6.1966

Peer-review started: August 16, 2021

First decision: October 22, 2021

Revised: October 27, 2021

Accepted: January 14, 2022

Article in press: January 14, 2022

Published online: February 26, 2022

Processing time: 191 Days and 1.5 Hours

There are multiple causes of sudden gastrointestinal bleeding in children. Reports of Dieulafoy lesions (DLs) in children are scarce. DLs can be fatal without appropriate treatment.

We present a retrospective analysis of the clinical manifestations, endoscopic features, and treatment of a Chinese girl with a DL, as well as a review of the relevant literature. A 10-year-old girl was admitted to our hospital with sudden massive hematemesis and melena. Abdominal computed tomography revealed suspected submucosal bleeding in the stomach. Finally, the disease was diagnosed with endoscopy due to the typical manifestations. We used electrocoagulation and hemoclips under endoscopy for hemostasis. No recurrence of hematemesis was identified during 4-wk’ follow-up.

DLs in children are rare but an important cause of sudden gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Many pediatricians are inexperienced and often miss or delay diagnosis. Endoscopy as early as possible is the first choice for diagnosis and treatment.

Core Tip: Dieulafoy lesions (DLs) are vascular abnormalities consisting of tortuous, dilated aberrant submucosal vessels. We present a 10-year-old girl with acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage due to a DL. We used electrocoagulation and hemoclips under endoscopy for hemostasis. This case highlights that while DLs in children are rare, they can be an important cause of sudden gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Many pediatricians are inexperienced and often miss or delay diagnosis. Endoscopy as early as possible is the first choice for diagnosis and treatment.

- Citation: Chen Y, Sun M, Teng X. Therapeutic endoscopy of a Dieulafoy lesion in a 10-year-old girl: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(6): 1966-1972

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i6/1966.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i6.1966

The most common causes of acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage are peptic ulcers and esophageal and gastroduodenal erosions[1]. However, even after careful investigations, such as endoscopy and barium studies, obscure gastrointestinal hemorrhages remain a clinical challenge. Dieulafoy lesions (DLs), also known as Dieulafoy disease, are a rare but fatal cause of gastrointestinal hemorrhage[2]. DLs are defined as vascular abnormalities consisting of tortuous, dilated aberrant submucosal vessels that do not undergo normal distal branching or tapering and subsequently protrudes through a minute defect into the overlying mucosa without ulceration[3]. DLs are scarce and it is hard to determine their true incidence in children. We performed a literature search on PubMed, Medline, and Embase, using the MeSH terms Dieulafoy lesion, Dieulafoy disease, Dieulafoy ulcer, and caliber persistent artery. Only 26 case reports of pediatric DLs were reported worldwide during 1995–2021, and there has been no literature review of DLs in children. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are vital. DLs must be considered in the differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal hemorrhage of unknown origin and not just in adults. We report a 10-year-old girl presenting with hematemesis and melena who was diagnosed with DL and successfully treated with electrocoagulation and hemoclips, and our experience in the diagnosis and treatment of DL in this child, and provide some data on DLs to pediatricians.

A 10-year-old Chinese girl with a history of hematemesis was admitted to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University with massive hematemesis and melena.

The girl presented with recurrent hematemesis 4-6 times 24 h before admission, with no obvious regularity. She denied overeating or eating excitant food. She did not take in any corrosive or sharp foreign body. She presented with the usual upper abdominal pain. As usual, there was no acid reflux or heartburn. She complained of belching and black stools.

At the age of 8 years, she was hospitalized with massive hematemesis. No erosions or ulcers were detected by endoscopy. After 4 d of treatment with blood transfusions and proton pump inhibitors, the active bleeding stopped, and the patient was discharged with our lack of understanding of DLs.

She denied any surgical history and was not taking any medication. She denied any history of drug or food allergies. There were no known significant gastrointestinal conditions in the family.

On her admission physical examination, her temperature was 36.5 ℃, heart rate 134 beats/min, blood pressure 96/56 mmHg, respiratory rate 25 breaths/min, and body weight 40 kg. She was pale, but her abdominal examination was unremarkable. No other physical abnormalities were noted.

Her initial laboratory testing revealed microcytic anemia. The coagulation test showed decreased fibrinogen. Liver function and myocardial enzymes were normal. In renal function, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level was elevated, and creatinine was normal. The high level of BUN is an important signal for upper intestinal bleeding. The results of other laboratory tests were unremarkable. Table 1 shows the details of the test results.

| Item | Measured value | Range of normal value |

| White blood cell | 12.7 × 109/L | 4-10 × 109/L |

| Hemoglobin | 7.8 g/dL | 12-15.5 g/dL |

| Hematocrit | 22.25% | 37%-47% |

| Platelet count | 134 × 109/L | 100-300 × 109/L |

| Prothrombin time | 15.3 s | 9.4-12.5 s |

| International normalized ratio | 1.4 | 0.8-1.2 |

| Fibrinogen | 1.7 g/L | 2-4 g/L |

| Albumin | 35.6 g/L | 35-53 g/L |

| Alanine transaminase | 8 U/L | 0-40 U/L |

| Glutamic oxalacetic transaminase | 14 U/L | 5-34 U/L |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 8.95 mmol/L | 2.5-7.2 mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 40.1 umol/L | 45-84 umol/L |

| Creatine kinase | 63 U/L | < 145 U/L |

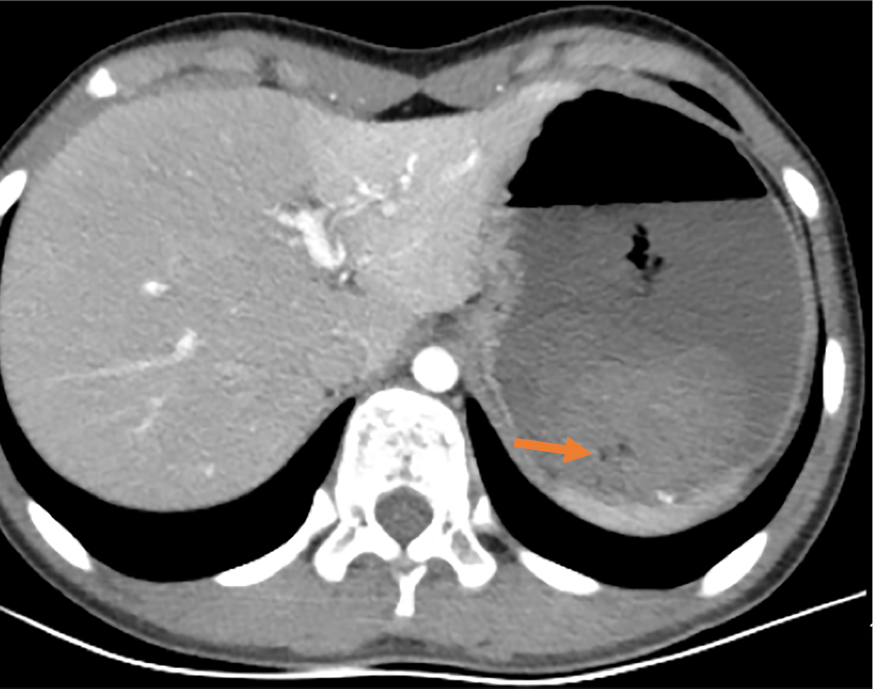

Abdominal enhanced computed tomography showed that the stomach was visibly dilated and filled with fluid, and blood clots were visible (Figure 1).

On the day of admission, she was managed with a proton pump inhibitor (1 mg/kg/d), fasting, gastrointestinal decompression, and nutritional support. According to the document “Standardize the diagnosis and treatment of acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding based on the update guidelines”, gastric lavage was performed with norepinephrine and ice saline[4]. She stopped vomiting but developed another massive melena and her hemoglobin decreased to 6.9 g/dL. Two units of packed red blood cells were transfused.

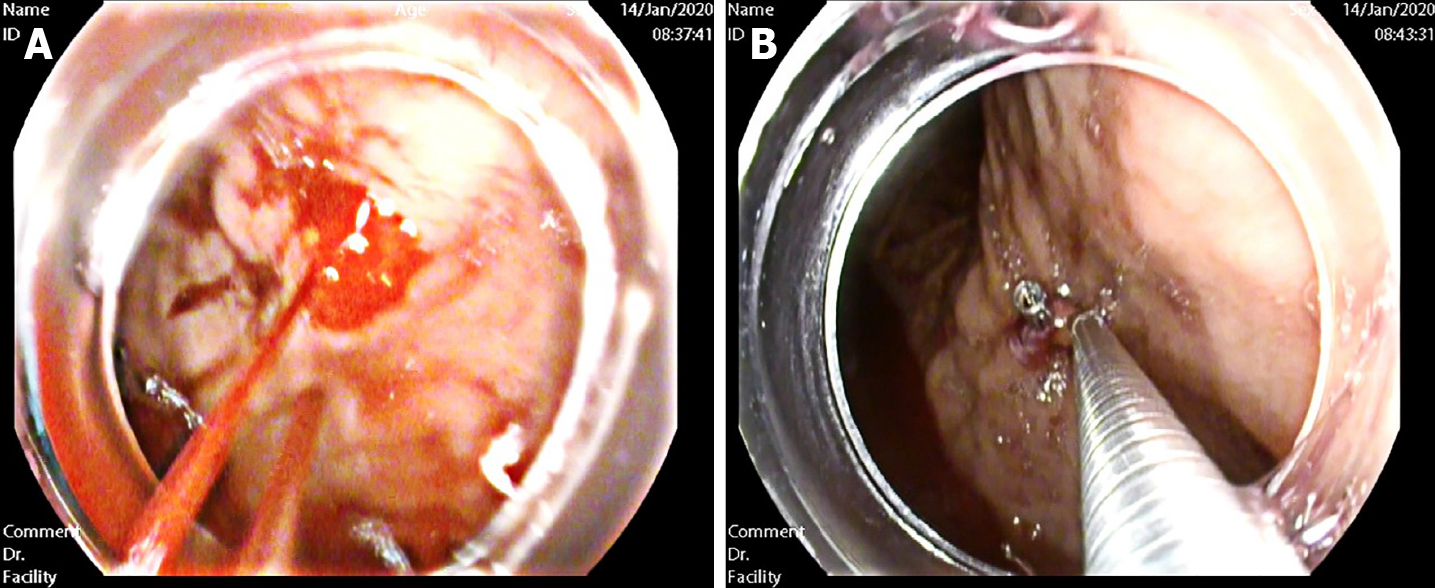

To find the cause and stop the bleeding, she was transferred to our department. After repeated communication with her parents, gastroscopy with a transparent hood over the head was urgently performed. To fully expose the observation field, we injected gas into the gastric cavity to expand the folds of the gastric mucosa. Then, we used normal saline to clean the blood scab covering the mucosal surface of the gastric body and fundus. Meanwhile, the residual blood in the stomach was continuously sucked out. A careful examination revealed the presence of an actively bleeding protruding vessel in the posterior wall of the body of the stomach (Figure 2A). Based on the patient’s history and typical endoscopic manifestation, DL was finally diagnosed.

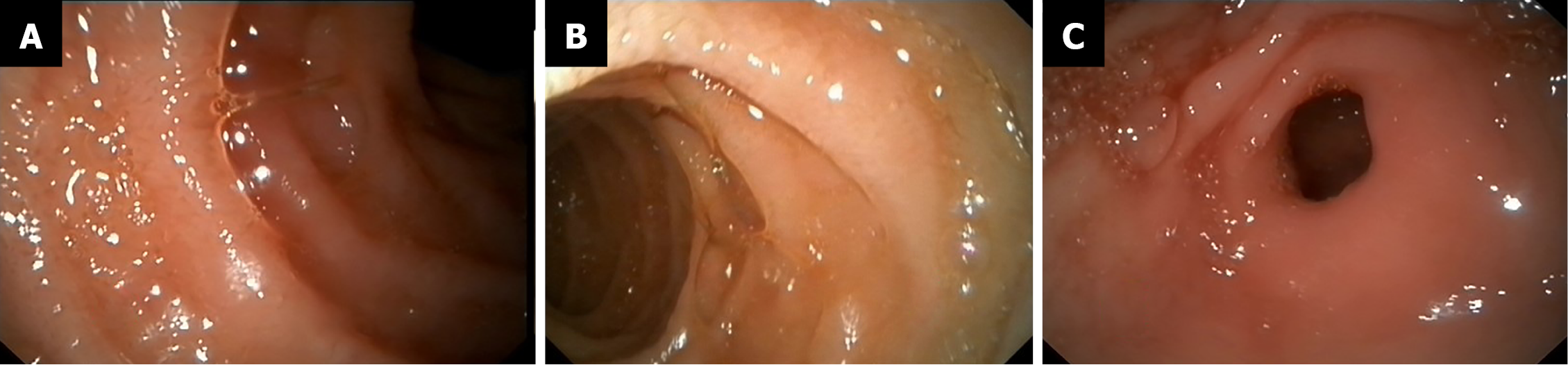

We treated the DL with electrocoagulation hemostatic forceps (FD-410LR; Olympus) and hemoclips [ROCC-D-26-195; Micro-Tech (Nanjing) Co. Ltd]. We inserted the hemostatic forceps to the bleeding site through the biopsy hole and accurately clamped the upper end of the bleeding artery. Electrocoagulation lasted 2–3 s and the power used in electrocoagulation (ESG-400) was 40 W. Two endoscopic hemoclips were applied, which achieved full control of the bleeding (Figure 2B). The hemoclips were opened to the maximum, perpendicular to the lesion, and clamped on the mucosa on both sides of the bleeding lesion, placing the bleeding focus in the middle. After sealing the bleeding focus, the two clips were fixed in an upright position and could not move, which indicated that the clips were firmly clamped. After the active bleeding had stopped and the residual blood in the stomach was sucked up, further examination of the gastric and duodenal mucosa showed no other bleeding spots, erosions, or ulcers (Figure 3).

The patient had no further complaints at her follow-up at the outpatient clinic 4 wk later.

DL, first described by the French pathologist Dieulafoy, manifests with spontaneous recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding. It is observed in 0.3%–6.7% of cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding[5]. There are no accurate statistics on the incidence of this disease in children. From 1995 to 2021, only sporadic cases were reported in children worldwide. DL is a large penetrating artery that is a normal vessel with an unexpectedly large diameter. The vessel caliber is 1-3 mm. This penetrating artery creates a small wall defect with fibrinoid necrosis at the base. The mechanisms of the pathological bleeding of DLs remain unknown. Newborn cases suggest that DLs can be congenital, and a congenital anomaly may develop acute ruptures. Mechanical friction, chemical corrosion, or drugs can induce the rupture of the protruding vessel and massive bleeding[6,7]. In adults, DLs are more common in men than women, and in middle-aged and older people[8]. Unlike adult patients, pediatric cases do not appear to have a gender predominance[9].

The small nature of the lesion and the special sites of the hemorrhage are two features of DLs. Most lesions are in the proximal stomach, particularly within 6–10 cm of the lesser curvature of the stomach, where blood supply comes directly from the arteriae gastrica sinistra[10]. Nongastric sites, such as the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, rectum, and even the bronchus, are also involved in DLs[11]. In our case, the DL was located in the posterior wall of the body of the stomach.

It is challenging to diagnose DL because of the features of the disease. Endoscopy, angiography, and surgical search are the primary diagnostic modalities. Red blood cell scintigraphy can also detect the site of bleeding. Undoubtedly, endoscopy is the most feasible method. Initial endoscopy can precisely diagnose over 71% of cases[12]. As subtle lesions can exist, multiple endoscopies are needed in some patients. The endoscopic visual criteria of DLs include: (1) Active arterial spurting or micro pulsatile streaming from a mucosal defect < 3 mm; (2) Visualization of a vessel protruding from a slight defect or normal mucosa; or (3) A fresh blood clot adherent to a minute mucosal defect or a normal-appearing mucosa[13,14]. To clearly and safely diagnose a DL, the following principles should be included in an endoscopic examination[15]: (1) During the period of active bleeding, emergency endoscopy should be performed under anti-shock therapy; (2) The DL may be exposed by cleaning the gastric cavity with moderate endoscopic perfusion; (3) During endoscopy, patients may change their body position, if necessary; (4) The search for the cause of the hemorrhage, especially sudden massive hematemesis, should not be stopped after finding a mild peptic ulcer and esophageal varicose veins; and (5) If a DL is suspected, a focal tissue biopsy is strictly prohibited.

Timely endoscopy and treatment can decrease the mortality of DL[16]. Endoscopy is recommended as the first-line method of treatment[17]. Endoscopic treatments include thermal electrocoagulation, heat probe coagulation, laser photocoagulation, regional injection with epinephrine, sclerotherapy, norepinephrine injection, band ligation, and hemoclips[18,19]. Mechanical banding and hemoclips are more effective than thermal electrocoagulation and injection[13]. It has been reported that 23 patients with lesions were found under emergency endoscopy, and all lesions were successfully sealed with hemoclips for hemostasis. During follow-up, there was no recurrence, suggesting that hemoclips are preferred for endoscopic treatment of DLs[20]. The combination of electrocoagulation and hemoclips may be more reliable. This procedure was adopted in our case.

For patients who fail in endoscopic therapy, angiography with gel foam embolization is suggested[21]. Surgical management, previously regarded as the only treatment available, is reserved for patients who are refractory to endoscopy and angiography. Endoscopy combined with laparoscopic surgery is a new procedure that is less invasive than traditional surgery and more readily accepted by patients[22].

Our patient’s endoscopic appearance was a typical manifestation of DL. Electrocoagulation and hemoclip treatment were effective, and no active bleeding occurred during follow-up. This case suggests that although DL is a rare occurrence in children, we cannot ignore it, especially in patients with sudden, acute, severe, or unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding. Moreover, the timing of endoscopy is important. If the patient’s condition permits, gastroscopy should be undertaken as early as possible. Besides diagnostic purpose, endoscopic hemostasis can also be performed.

DL, as a cause of life-threatening bleeding, is a rare occurrence in the pediatric population. However, pediatricians should be aware of it as a differential diagnosis of pediatric gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy is still the primary diagnostic tool and the first-line method of treatment. Early diagnosis and treatment are of great significance for a good prognosis in children.

We thank International Science Editing for editing this manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Oda M, Yoshimatsu K S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Lirio RA. Management of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Children: Variceal and Nonvariceal. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2016;26:63-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zamulko OY, Zamulko AO, Dawson MJ. Introducing GIST and Dieulafoy - Think of Them in GI Bleeding and Anemia. S D Med. 2019;72:528-530. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Inayat F, Ullah W, Hussain Q, Hurairah A. Dieulafoy's lesion of the oesophagus: a case series and literature review. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bai Y, Li ZS. Standardize the diagnosis and treatment of acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding based on the update guidelines. Zhongguo Neike Zazhi. 2019;58:161-163. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chaer RA, Helton WS. Dieulafoy's disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:290-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chen QK, He GX, Zhu ZH. Diagnosis of digestive disease. 2nd ed. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House 2006: 418. |

| 7. | Gambhire PA, Jain SS, Rathi PM, Amarapurkar AD. Dieulafoy disease of stomach--an uncommon cause of gastrointestinal system bleeding. J Assoc Physicians India. 2014;62:526-528. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Holleran G, Hussey M, McNamara D. Small bowel Dieulafoy lesions: An uncommon cause of obscure bleeding in cirrhosis. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8:568-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Senger JL, Kanthan R. The Evolution of Dieulafoy's Lesion Since 1897: Then and Now-A Journey through the Lens of a Pediatric Lesion with Literature Review. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:432517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tang P, Wu T, Li C, Lv C, Huang J, Deng Z, Ding Q. Dieulafoy disease of the bronchus involving bilateral arteries: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e17798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Joarder AI, Faruque MS, Nur-E-Elahi M, Jahan I, Siddiqui O, Imdad S, Islam MS, Ahmed HS, Haque MA. Dieulafoy's lesion: an overview. Mymensingh Med J. 2014;23:186-194. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Driver CP, Bruce J. An unusual cause of massive gastric bleeding in a child. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1749-1750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chung IK, Kim EJ, Lee MS, Kim HS, Park SH, Lee MH, Kim SJ, Cho MS. Bleeding Dieulafoy's lesions and the choice of endoscopic method: comparing the hemostatic efficacy of mechanical and injection methods. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:721-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Apiratpracha W, Ho JK, Powell JJ, Yoshida EM. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding from a dieulafoy lesion proximal to the anorectal junction post-orthotopic liver transplant. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7547-7548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Xu X, Zhang YS, Yuan J, Zhang ZY. Diagnosis and treatment of dieulafoy disease. Zhongguo Weichangbingxue Ganbingxue Zazhi. 2009;18:870-871. |

| 16. | Alshumrani G, Almuaikeel M. Angiographic findings and endovascular embolization in Dieulafoy disease: a case report and literature review. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2006;12:151-154. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Jeon HK, Kim GH. Endoscopic Management of Dieulafoy's Lesion. Clin Endosc. 2015;48:112-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Baxter M, Aly EH. Dieulafoy's lesion: current trends in diagnosis and management. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:548-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Alis H, Oner OZ, Kalayci MU, Dolay K, Kapan S, Soylu A, Aygun E. Is endoscopic band ligation superior to injection therapy for Dieulafoy lesion? Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1465-1469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Li F, Li YX, Shen L. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of 23 Dieulafoy's disease. J Clin Intern Med. 2011;19:821-822. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Ganganah O, Guo S, Chiniah M, Sah SK, Wu J. Endobronchial ultrasound and bronchial artery embolization for Dieulafoy's disease of the bronchus in a teenager: A case report. Respir Med Case Rep. 2015;16:20-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yılmaz TU, Kozan R. Duodenal and jejunal Dieulafoy's lesions: optimal management. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2017;10:275-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |