Published online Feb 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1723

Peer-review started: October 18, 2021

First decision: October 27, 2021

Revised: November 4, 2021

Accepted: January 8, 2022

Article in press: January 8, 2022

Published online: February 16, 2022

Processing time: 116 Days and 1.7 Hours

Metastatic tumors are the most common malignancies of central nervous system in adults, and the frequent primary lesion is lung cancer. Brain and leptomeningeal metastases are more common in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harboring epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. However, the coexist of brain metastasis with leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) in isolated gyriform appearance is rare.

We herein presented a case of a 76-year-old male with an established diagnosis as lung adenocarcinoma with gyriform-appeared cerebral parenchymal and leptomeningeal metastases, accompanied by mild peripheral edema and avid contrast enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging. Surgical and pathological examinations confirmed the brain and leptomeningeal metastatic lesions in the left frontal cortex, subcortical white matter and local leptomeninges.

This case was unique with respect to the imaging findings of focal gyriform appearance, which might be caused by secondary parenchymal brain metastatic tumors invading into the leptomeninges or coexistence with LM. Radiologists should be aware of this uncommon imaging presentation of tumor metastases to the central nervous system.

Core Tip: Patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harboring epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations were more susceptible to develop into brain or leptomeningeal metastases when compared to those with wild-type EGFR. However, parenchymal brain metastasis combined with leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) in isolated gyriform appearance is rare. We herein presented a case of a 76-year-old male with EGFR-mutated lung adenocarcinoma metastases of the brain with isolated gyriform appearance in imaging findings. We speculated that the focal gyriform lesions were likely to be caused by secondary leptomeningeal invasion from parenchymal brain metastatic tumors or coexisting of parenchymal brain metastasis with LM.

- Citation: Li N, Wang YJ, Zhu FM, Deng ST. Unusual magnetic resonance imaging findings of brain and leptomeningeal metastasis in lung adenocarcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(5): 1723-1728

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i5/1723.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1723

Metastatic tumors account for the majority of central nervous system (CNS) neoplasms, which outnumber the primary brain tumors, and the most common source for these is lung cancer[1]. CNS metastasis involves brain parenchyma, dura or leptomeninges. Neuroimaging findings often indicate metastatic diseases. In particular, the gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is regarded beneficial for the detection of leptomeningeal metastasis (LM)[2]. Herein, we presented a case of a 76-year-old male with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutated lung adenocarcinoma metastases of the brain with unique appearance in imaging findings.

A 76-year-old male patient with nausea and vomiting without obvious inducement, and dizziness, headache and fatigue was admitted to our hospital for further evaluation.

Patient’s symptoms started 3 d ago.

In 2014, the patient underwent radical resection of the right middle lobe lung cancer for the first time. The postoperative diagnosis showed lung adenocarcinoma (T1aN0M0, stage Ia), without adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy. In January 2019, the patient underwent a puncture biopsy because of the newly discovered ground-glass nodule in the right lower lung, and postoperative pathology confirmed lung adenocarcinoma. Polymerase chain reaction of tumor specimens showed EGFR mutations at exon 21. Radiofrequency ablation of right lung cancer was performed after the surgery. At this time, MRI of brain showed no metastatic tumors in the central nervous system.

The patient had no particular individual or family history.

Neurological examination was conducted, which revealed no obvious pathological signs of tumor metastasis.

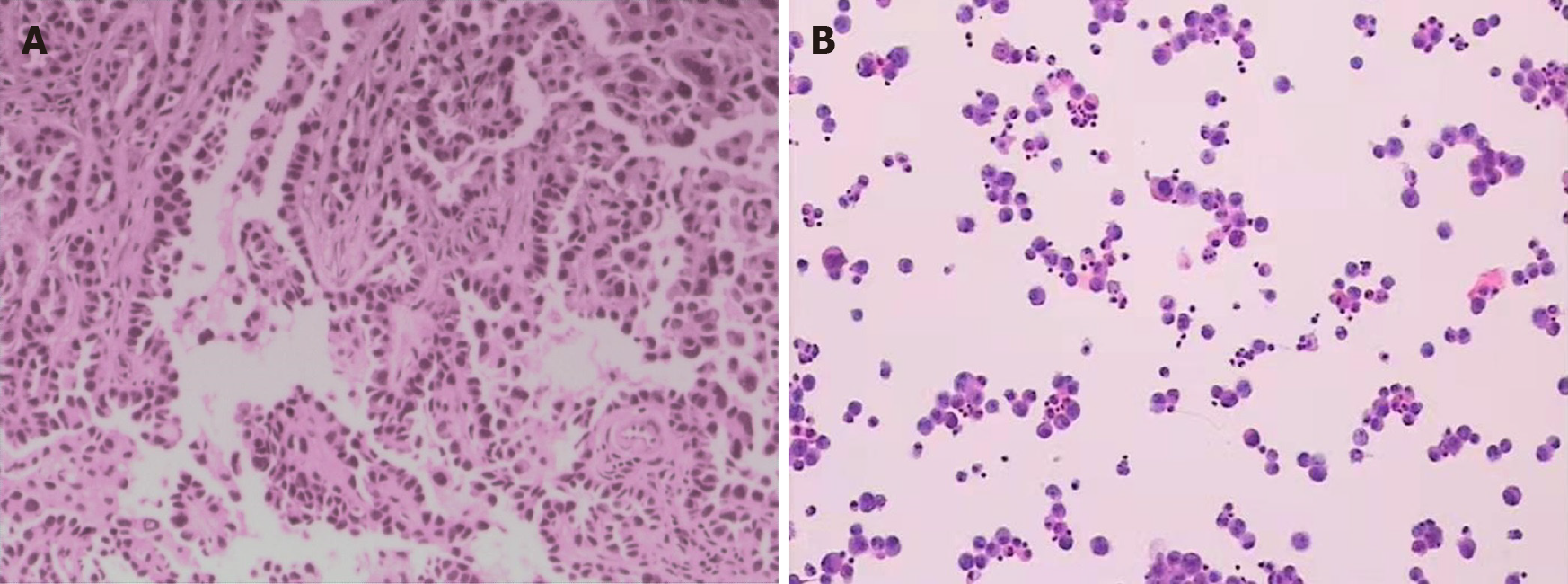

The patient underwent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tests 2 mo after craniotomy. The CSF results were as follows: Glucose: 0.7 mmol/L; Chloride: 117.4 mmol/L; β-trace protein: 2283 mg/L; White cell: 220 × 106/L; Neutrophils: 20%; and Lymphocytes: 80%. The Pandy’s test was positive, and CSF cytology showed malignant epithelial cells in the CSF (Figure 1).

In October 2019, MRI of the brain (Figure 2) revealed a cortical and subcortical isolated gyriform mass in the left frontal lobe, with T2/FLAIR hyperintensities, obvious contrast enhancement, subtle perilesional edema, and restricted diffusion, which was unusual for metastatic tumors. Therefore, it was misdiagnosed as glioma or subacute cerebral infarction. In addition, T1WI enhancement also revealed local leptomeningeal lesions (Figure 2E), which were missed in the process of imaging diagnosis. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) showed no obvious abnormalities in the intracranial blood vessels.

Due to ambiguity in imaging findings, craniotomy was performed to establish the diagnosis. During operation, the mass was shown to be located in the left frontal lobe and adjacent leptomeninges, with a local gray-white tumor tissue, wherein a small part of it appeared pink fish-like, and had abundant blood supply. Resection of tumor tissue was performed in the frontal lobe, and then along the cerebral gyrus and sulcus to remove the invasive residual tumors and leptomeningeal lesions. The pathological examination results revealed abnormal epithelioid cell nests in the brain tissue (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical stains were positive for cytokeratin 7, thyroid transcription factor-1, Napsin-A, and epithelial membrane antigen and negative for glial fibrillary acidic protein, P53, S-100, Vim and ALK, which was consistent with that of primary lung metastasis. Also 40% proliferative activity was reported with Ki-67.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was brain and leptomeningeal metastases in EGFR-mutated lung adenocarcinoma.

After surgery, the patient's condition was stabilized, but his consciousness was still clouded.

The patient did not receive chemotherapy after surgery and died due to acute brain failure two months later.

Lung cancer is the most common primary tumor associated with CNS metastases, and it eventually develops into CNS metastases in 23%-36% of lung cancer patients[3]. LM is rare and occurs in 3%-5% of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer[4]. Patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harboring EGFR mutations were more susceptible to develop brain or leptomeningeal metastases when compared with those bearing wild-type EGFR[5,6]. Patterns of brain metastasis might vary in non-small cell lung cancer patients, as it depends on the tumor nodules and is more or less related to cystic and necrotic lesions[7,8]. However, parenchymal brain metastasis combined with LM in the appearance of isolated gyriform are rare. After all, LM usually presents as more diffused tumor involvement, and isolated one is not frequently seen. A case of EGFR-mutated lung adenocarcinoma with brain parenchymal and leptomeningeal metastases in a focal gyriform appearance was herein presented.

The lesions of left frontal cortex, subcortex and local leptomeninges, forming an isolated gyriform, were shown with avid contrast enhancement in our case, which was considered to be rare in tumor metastasis into the CNS. Making a diagnosis of LM is difficult, which is relied on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis result, and clinical and radiographic findings. CSF cytology remains the gold standard for diagnosing LM, but it is invasive and associated with relatively low sensitivity[9]. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI of the brain is considered to be the best imaging technique for evaluating LM, and the images of LM appear as nodular, linear, arched, focal or diffuse intensification[2,10]. The clinical manifestations of the patient in this case were non-specific, and cytological examination of CSF was not performed before operation. LM was also neglected during preoperative MRI diagnosis. Compared with T1WI enhancement sequence, the contrast-enhanced T2-weighted FLAIR sequence is more sensitive to detect leptomeningeal tumoral or infective-inflammatory involvement. A limitation of this study was that other smaller areas of metastasis on the leptomeningeal surface may be ignored because contrast-enhanced T2-weighted FLAIR was not taken. LM was eventually discovered during the surgery. CSF cytology examination also showed malignant tumor cells 2 months later. In fact, preoperative T1WI enhancement in the present case had significantly revealed LM (Figure 2E).

Similar to the pathophysiology of brain metastases, LM was likely to be a multistep biological process[11]. The spread of cancer cells to leptomeninges might occur via multiple routes, including direct metastatic brain tumors infiltration, hematogenous dissemination of tumors, or via endoneurial/perineural and perivascular pathways[12]. The imaging and intraoperative findings of this case confirmed the seeding of tumors into the brain parenchyma and leptomeninges. Therefore, we speculated that the isolated gyriform lesions were likely metastatic brain parenchymal tumors with secondary leptomeningeal infiltration or a coexistence of brain metastasis with LM.

Moreover, the patient’s MR imaging showed only mild white matter edema below the lesions, which was different from the extensive edema surrounding the typical metastatic tumors. The extracellular space of white matter was wider than that of the gray matter, so white matter was prone to edema. It was speculated that the mild peritumoral edema was related to tumors mainly located in the cortex.

The prognosis of non-small cell lung carcinoma with LM remained poor, and the median overall survival was only 3 mo [5]. Systemic chemotherapy is the preferred treatment choice for lung cancer patients with LM[13]. In this case, the patient had brain and leptomeningeal metastases, and underwent surgical resection without postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. His condition worsened after surgery and died due to brain failure 2 mo after the diagnosis of CNS metastasis.

Intracranial focal gyriform lesions should be distinguished from cerebral infarction in elderly patients. In subacute infarction, cortical edema and necrosis may lead to enhanced gyral lesions, and may even lead to leptomeningeal enhancement lesions due to meningeal inflammation and early fibrosis[14]. But the enhanced lesions of subacute cerebral infarction demonstrated no obvious mass effect, and the cerebral parenchyma around the enhanced lesions also showed varying degrees of ischemia. However, the mass effect of intracranial enhancement lesions in the present case was obvious, and no adjacent brain parenchyma was involved. Moreover, the clinical manifestations of this patient included only nausea and vomiting, and no symptoms of stroke.

Besides, the diagnosis of this case should be differentiated from high-grade gliomas on imaging. High-grade gliomas tend to occur in the subcortical white matter, and large tumors can cause white matter necrosis, showing circular enhancement images. Furthermore, metastatic peritumoral edema is purely vasogenic, and no infiltrating tumor cells are present outside the perivascular space, which leads to hypoperfusion, with relatively normal magnetic resonance spectrum (MRS) in the peritumoral edema area. The peritumoral edema of high grade gliomas, on the other hand, is a mixture of vasogenic edema, infiltrating neoplastic cells and feeding blood vessels, which is expected to have an increased blood perfusion and higher Cho/NAA and Cho/Cr ratios on MRS, compared to solitary brain metastases[15,16]. Therefore, perfusion-weighted imaging and MRS of peritumoral edema could assist in differential diagnosis of high-grade gliomas versus brain metastases, but the patient didn't receive these tests.

In addition, this case should also be differentiated from cases of leptomeningeal involvement diseases, such as primary central nervous system vasculitis (PCNSV) and tuberculous meningitis (TBM). Unlike the isolated cortical mass in this case, the common MRI features of PCNSV are multiple bilateral supratentorial lesions, involving the gray and white matter, predominantly in the subcortex, deep white matter and corpus callosum, accompanied with focal cerebral infarction[17]. Although PCNSV images could manifest as irregular linear enhancement on subcortical white matter and leptomeninges, there was no obvious mass effect. TBM tended to occur at basal areas, with multiple bilateral foci and obstructive hydrocephalus, which could be differentiated from CNS metastases.

A rare case of EGFR-mutated lung adenocarcinoma with cerebral parenchymal and leptomeningeal metastases characterized by isolated gyriform appearance was reported. We speculated that this unique appearance is likely to be due to the induction of secondary leptomeningeal invasion from parenchymal brain metastasis or coexisted with LM. Therefore, when patients with a history of lung adenocarcinoma were dealt, radiologists should be aware of this uncommon imaging presentation of CNS metastases and carefully observe for the existence of leptomeningeal lesions on T1 enhancement to avoid missed diagnosis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited manuscript; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Neuroimaging

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chu HT, Gokce E, Musoni L S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Sloan AE, Davis FG, Vigneau FD, Lai P, Sawaya RE. Incidence proportions of brain metastases in patients diagnosed (1973 to 2001) in the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2865-2872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1043] [Cited by in RCA: 1235] [Article Influence: 58.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chamberlain M, Junck L, Brandsma D, Soffietti R, Rudà R, Raizer J, Boogerd W, Taillibert S, Groves MD, Le Rhun E, Walker J, van den Bent M, Wen PY, Jaeckle KA. Leptomeningeal metastases: a RANO proposal for response criteria. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19:484-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ostrom QT, Wright CH, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. Brain metastases: epidemiology. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;149:27-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Remon J, Le Rhun E, Besse B. Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis in non-small cell lung cancer patients: A continuing challenge in the personalized treatment era. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;53:128-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Li YS, Jiang BY, Yang JJ, Tu HY, Zhou Q, Guo WB, Yan HH, Wu YL. Leptomeningeal Metastases in Patients with NSCLC with EGFR Mutations. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:1962-1969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li L, Luo S, Lin H, Yang H, Chen H, Liao Z, Lin W, Zheng W, Xie X. Correlation between EGFR mutation status and the incidence of brain metastases in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:2510-2520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Essenmacher AC, Watal P, Bathla G, Bruch LA, Moritani T, Capizzano AA. Brain metastases from adenocarcinoma of the lung with truly cystic magnetic resonance imaging appearance. Clin Imaging. 2018;52:203-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sakatani T, Kage H, Takayanagi S, Watanabe K, Hiraishi Y, Shinozaki-Ushiku A, Tanaka S, Ushiku T, Saito N, Nagase T. Brain Metastasis Mimicking Brain Abscess in ALK-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2019;2019:9141870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gil B, Hwang EJ, Lee S, Jang J, Choi HS, Jung SL, Ahn KJ, Kim BS. Detection of Leptomeningeal Metastasis by Contrast-Enhanced 3D T1-SPACE: Comparison with 2D FLAIR and Contrast-Enhanced 2D T1-Weighted Images. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yang G, Pan Z, Ma N, Qu L, Yuan T, Pang X, Yang X, Dong L, Liu S. Leptomeningeal metastasis of pulmonary large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:4282-4286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fidler IJ, Yano S, Zhang RD, Fujimaki T, Bucana CD. The seed and soil hypothesis: vascularisation and brain metastases. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:53-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chang EL, Lo S. Diagnosis and management of central nervous system metastases from breast cancer. Oncologist. 2003;8:398-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Park JH, Kim YJ, Lee JO, Lee KW, Kim JH, Bang SM, Chung JH, Kim JS, Lee JS. Clinical outcomes of leptomeningeal metastasis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer in the modern chemotherapy era. Lung Cancer. 2012;76:387-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Castillo M, Scatliff JH, Kwock L, Green JJ, Suzuki K, Chancellor K, Smith JK. Postmortem MR imaging of lobar cerebral infarction with pathologic and in vivo correlation. Radiographics. 1996;16:241-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Halshtok Neiman O, Sadetzki S, Chetrit A, Raskin S, Yaniv G, Hoffmann C. Perfusion-weighted imaging of peritumoral edema can aid in the differential diagnosis of glioblastoma mulltiforme vs brain metastasis. Isr Med Assoc J. 2013;15:103-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Aslan K, Gunbey HP, Tomak L, Incesu L. Multiparametric MRI in differentiating solitary brain metastasis from high-grade glioma: diagnostic value of the combined use of diffusion-weighted imaging, dynamic susceptibility contrast imaging, and magnetic resonance spectroscopy parameters. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2019;53:227-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang LJ, Kong DZ, Guo ZN, Zhang FL, Zhou HW, Yang Y. Study on the Clinical, Imaging, and Pathological Characteristics of 18 Cases with Primary Central Nervous System Vasculitis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28:920-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |