Published online Nov 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i32.12015

Peer-review started: August 1, 2022

First decision: September 5, 2022

Revised: September 13, 2022

Accepted: October 17, 2022

Article in press: October 17, 2022

Published online: November 16, 2022

Processing time: 98 Days and 22.1 Hours

The ascending pharyngeal artery (APhA) comprises the pharyngeal trunk (PT) and neuromeningeal trunk. The PT feeds the nasopharynx and adjacent tissue, which potentially connects with the sphenopalatine artery (SPA), branched from the internal maxillary artery (IMA). Due to its location deep inside the body, the PT is rarely injured by trauma. Here, we present two cases that underwent transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) of the PT of the APhA due to trauma and iatrogenic procedure.

Case 1 is a 49-year-old Japanese woman who underwent transoral endoscopy under sedation for a medical check-up. The nasal airway was inserted as glossoptosis occurred during sedation. Bleeding from the nasopharynx was observed during the endoscopic procedure. As the bleeding continued, the patient was referred to our hospital for further treatment. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) demonstrated extravasation in the nasopharynx originating from the right Rosenmuller fossa. TAE was performed and the extravasation disappeared after embolization. Case 2 is a 28-year-old Japanese woman who fell from the sixth floor of a building and was transported to our hospital. Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrated a complex facial fracture accompanying extravasation in the left pterygopalatine fossa to the nasopharynx. Angiography demonstrated an irregular third portion of the IMA. As angiography after TAE of the IMA demonstrated extravasation from the PT of the APhA, additional TAE to the artery was performed. The bleeding stopped after the procedure.

Radiologists should be aware that the PT of the APhA can be a bleeding source, which has a potential connection with the SPA.

Core Tip: The pharyngeal trunk (PT) of the ascending pharyngeal artery (APhA) feeds the nasopharynx and adjacent tissue, which potentially has a connection with the sphenopalatine artery (SPA) branched from the internal maxillary artery. The PT is rarely injured due to its position deep inside the body; however, it may be a bleeding source of the nasopharynx in trauma patients. Moreover, the PT of the APhA might be a bleeding source after embolization of the SPA. Radiologists should be aware that the PT of the APhA, which potentially connects with the SPA, can be a bleeding source in patients with trauma.

- Citation: Yunaiyama D, Takara Y, Kobayashi T, Muraki M, Tanaka T, Okubo M, Saguchi T, Nakai M, Saito K, Tsukahara K, Ishii Y, Homma H. Transcatheter arterial embolization for traumatic injury to the pharyngeal branch of the ascending pharyngeal artery: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(32): 12015-12021

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i32/12015.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i32.12015

The ascending pharyngeal artery (APhA) originates from the external carotid artery or its branches and comprises the pharyngeal trunk (PT) and neuromeningeal trunk (NT)[1]. The NT is an important artery that supplies the lower cranial nerves and dura. Previous case reports involving these arteries have primarily focused on how to avoid neural complications[2]. The PT has also been discussed in patients with idiopathic epistaxis[3], benign or malignant neoplasm[3,4], trauma and iatrogenic damage[3,5,6], which is analogous to traumatic epistaxis. During iatrogenic procedures, the PT can be injured. Given its location deep inside the body, it can be difficult to stop the bleeding by compression.

Transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) is a well-established procedure in radiology[7]. Radiologists can effectively stop bleeding by TAE when the bleeding source is an artery. The indications of TAE to the APhA include meningioma[8], juvenile angiofibroma[9], paraganglioma[10], dural arteriovenous fistula[11], or hemorrhage due to various causes[6,12,13]. Among these pathologies, hemorrhage is an urgent issue because a large amount of hemorrhage can cause airway or circulation problems. Moreover, since hemorrhage cannot be compressed, TAE should be considered. Hemorrhage may be spontaneous, trauma or tumor-related. Among these causes, traumatic hemorrhage from the APhA is extremely rare as the area is located deep inside the body. However, radiologists should be aware that the PT of the APhA can lead to nasal hemorrhage. Moreover, the anatomy of the branches and sub-branches of the PT of the APhA are complicated and the APhA itself has a potential connection with the sphenopalatine artery (SPA) derived from the internal maxillary artery (IMA). This anatomical characteristic influences the embolization procedure for bleeding from the PT of the APhA. Here, we present two cases that underwent TAE of the PT of the APhA due to trauma.

Case 1: Epistaxis.

Case 2: Systemic trauma.

Case 1: A 49-year-old Japanese woman underwent transoral endoscopy during a medical check-up. An endoscope was inserted into the nasal airway as glossoptosis occurred during sedation. Bleeding from the nasopharynx occurred during the endoscopic procedure and the patient was referred to another hospital to manage the bleeding. The clinician decided to discharge the patient after observation for only one night because they considered the bleeding to have stopped. However, the patient felt that the bleeding continued and was referred to our hospital for further treatment (day 1 at our hospital).

Case 2: A 28-year-old Japanese woman who fell from the sixth floor of a building was transported to our hospital by ambulance.

Case 1: Nothing.

Case 2: Depression.

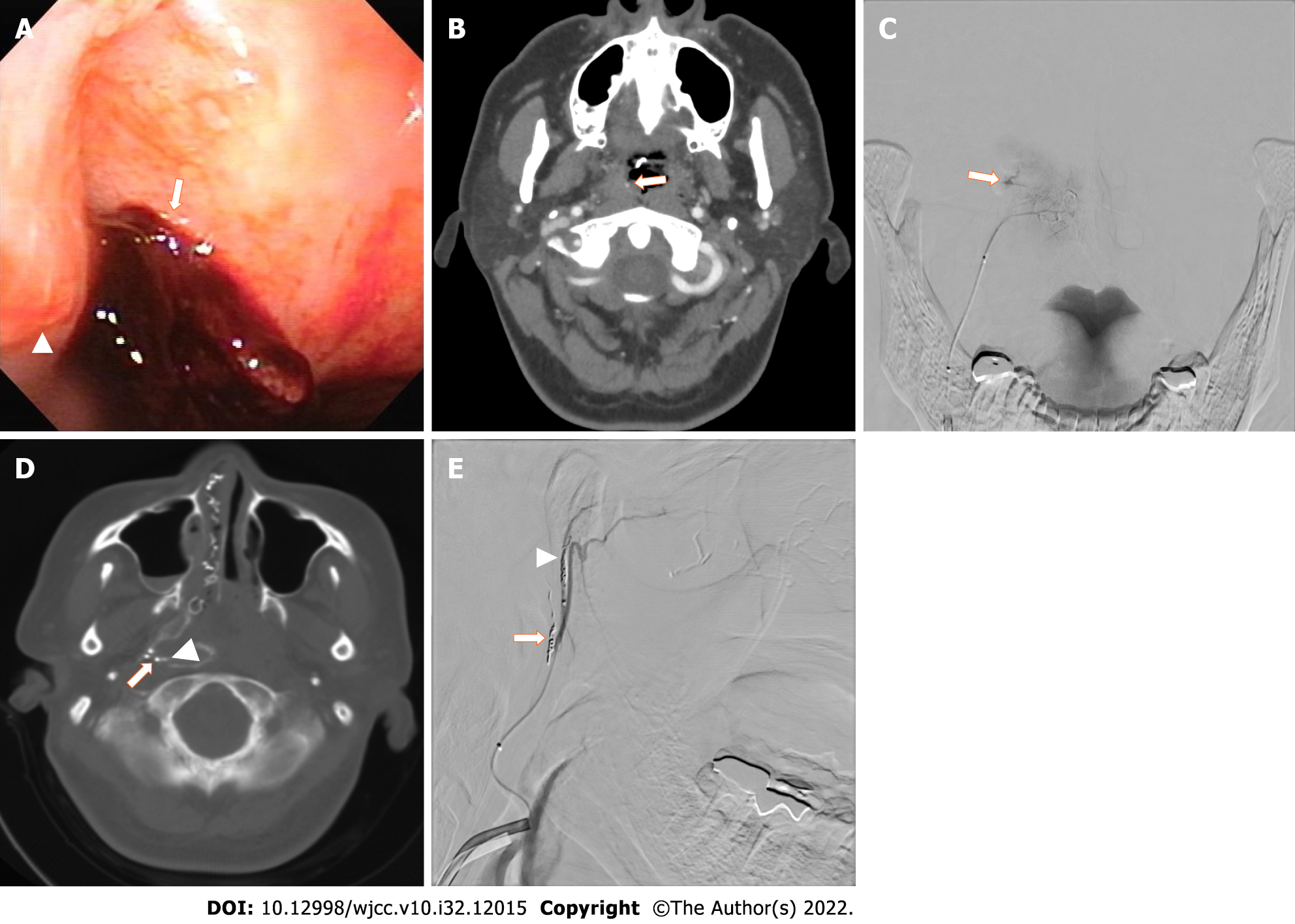

Case 1: An otorhinolaryngologist examined the patient’s nasopharynx via nasal endoscopy. The posterior left wall of the nasopharynx was covered in clots and bleeding was observed from the inside of the clot (Figure 1A).

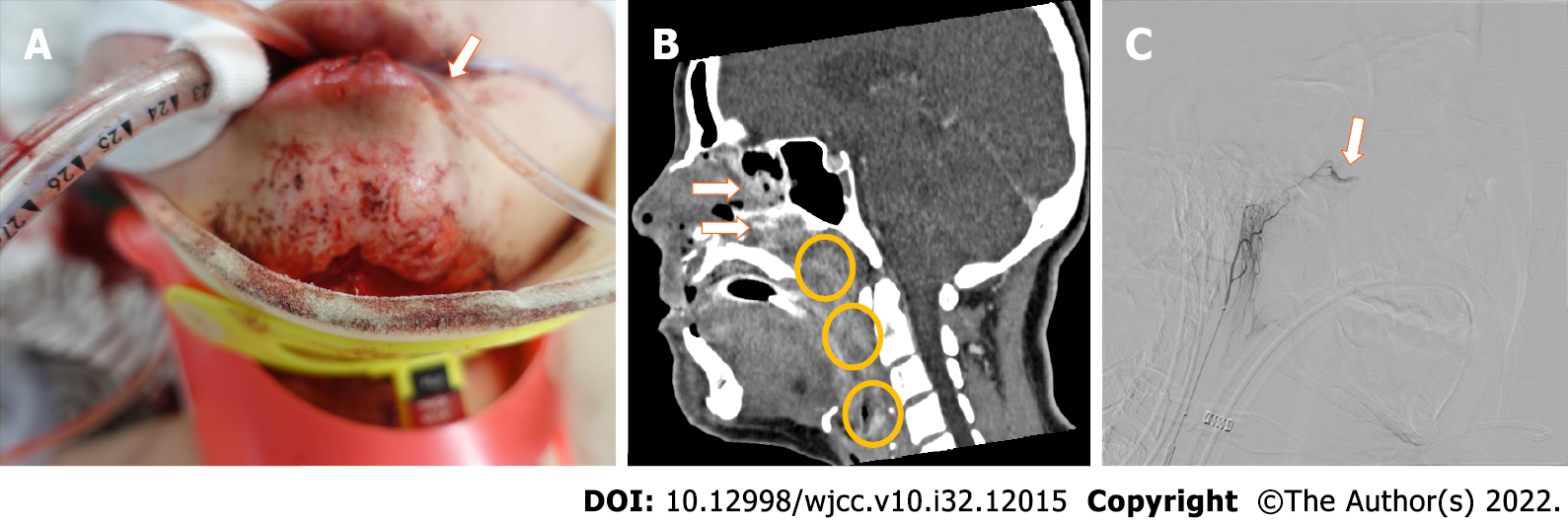

Case 2: The facial fracture was remarkable and an excessive nosebleed was observed. Bilateral temporal processes, mandibular processes, pterygoid plates, zygomatic arches, and Agger nasi were fractured. The bilateral, anterior, inferior and medial wall of the maxillary sinus and palatine bone were also fractured. Extremity fractures were also observed. Due to excessive nasal and transoral bleeding (Figure 2A), tracheal intubation was performed to secure the airway. The patient was in a state of shock with a blood pressure of 79/57 mmHg and a heart rate of 122/min. Rapid extracellular fluid administration and transfusion was performed. Since the response to the infusion was good, the origin of shock was considered to be hemorrhage.

Case 1: White blood counts (WBC): 13.5 × 103 /dL; Hb: 13.2 g/dL; Plt: 244 × 103 /dL; APTT: 36.9 s; and APTT control: 28.0 s.

Case 2: WBC: 25.5 × 103 /dL; Hb: 13.2 g/dL; Plt: 388 × 103 /dL; Fibrinogen: 172 mg/dL; D-dimer: 32.49 μg/mL; FDP: 56 μg/dL; PT: 13.8 s; PT control: 12.2 s; APTT: 25.5 s; APTT control: 27.9 s.

Case 1: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) demonstrated extravasation in the nasopharynx (Figure 1B) originating from the right Rosenmuller fossa. The otorhinolaryngologist inserted a balloon catheter in the nasopharynx and inflated it to compress the wall of the nasopharynx.

Case 2: A trauma pan scan was performed as the vital signs were maintained by infusion. Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrated complex facial fracture accompanying extravasation in the left pterygopalatine fossa to the nasopharynx through the sphenopalatine foramen (Figure 2B). Slight hepatic injury without extravasation was also observed on CT images.

Case 1: Iatrogenic nasopharyngeal injury.

Case 2: As clinicians and radiologists suspected that the major hemorrhage was in the nasopharynx, intervention was planned.

Case 1: The next day, angiography from the right PT of the APhA showed trauma causing extravasation (Figure 1C). Cone beam CT was performed in Xper CT mode (Philips Japan, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) by injecting 1:3 diluted 300 mgI contrast media at 0.5 mL/second (Figure 1D) to precisely reveal the anatomy. An artery to the Rosenmuller fossa was determined to be the representative vessel. A 0.010 inch coil of 1.5 mm × 4 cm size was placed in the branch of an artery of the Rosenmuller fossa. Two 0.010 inch coils measuring 1.5 mm × 3 cm and 1.0 mm × 3 cm were placed in the branch of the torus tubarius (Figure 1E). The extravasation disappeared angiographically just after the embolization.

Case 2: Angiography from the left external carotid artery demonstrated an irregular shape of the third portion of the IMA. Embolization with a gelatin sponge and coil to the third portion of the IMA was performed. Angiography after the procedure from the left external carotid artery demonstrated extravasation from the PT of the APhA (Figure 2C). A microcatheter was inserted into the PT of the APhA and embolization with a gelatin sponge was performed.

Case 1: The balloon catheter was deflated on day 6, after which no bleeding was observed via nasal endoscopy. The patient was discharged on day 8. The summary of the clinical timeline was shown in Table 1.

| Event | Case 1 | Case 2 |

| Initial injury | Day 0 | Day 1 |

| Referral to our hospital | Day 1 | Day 1 |

| Transarterial embolization | Day 2 | Day 1 |

| Discharge | Day 8 | Still hospitalized on day 68 |

Case 2: The bleeding stopped after the procedure. Plastic surgery for facial bone fractures and orthopedic surgery for extremity fractures were planned. The summary of the clinical timeline was shown in Table 1.

Epistaxis from the APhA caused by trauma is extremely rare as the region is located deep inside the body. To date, only a few cases of patients who underwent embolization for the PT of the APhA have been reported[6,13].

The anatomy of the PT of the APhA has been previously described to comprise superior, middle and inferior branches[1]. A branch of the Eustachian tube and musculospinal branch have also been described[14]. In Case 1, the artery of the Rosenmuller fossa was the source of bleeding. As this artery has not been described in previous reports, we propose naming it the “artery of Rosenmuller fossa.” The superior branch of the PT of the APhA comprises three sub-branches: Artery of Rosenmuller fossa, artery of torus tubarius and artery of the superior to the lateral wall, which might communicate with the posterior lateral nasal branch and posterior septal branch of the SPA, which was described as the maxillary branches by Lasjaunias and Moret[15]. Considering these anatomical features, proximal embolization of a sub-branch of the PT of the APhA would result in collateral perfusion from the adjacent branch. Therefore, we performed coil embolization of two sub-branches of the PT of the APhA in Case 1.

We could not determine the extravasation site of the PT of the APhA in Case 2 from the initial contrast-enhanced CT image. The likely reasons are as follows: (1) Bleeding started after CT was performed along with coagulopathy; and (2) Embolization of the third portion of the IMA resulted in collateral bleeding from the PT of the APhA. The latter is an important issue when performing embolization of the IMA in patients with epistaxis, as it is necessary to consider collateral flow from the PT to the APhA. Radiologists should consider the PT of the APhA as a bleeding source in patients who have undergone embolization of the IMA.

In Case 1, the insertion of the endoscope into the nasal airway may have injured the nasopharyngeal wall. A similar case has been previously described[6]. Inserting a medical device, e.g., a nasogastric tube or ileus tube, through the nasal space without directly watching the tip of the device is common. Clinicians and radiologists should know that inserting any medical device through the nasal space carries the risk of injuring the nasopharyngeal wall. Moreover, sites hidden from the endoscope, such as the Rosenmuller fossa, might be dangerous once bleeding is observed. Since stopping the bleeding by compression is difficult, TAE might be required.

The embolization materials in Case 2 were gelatin sponge and metallic coils. Gelatin sponge is usually the main choice of material to stop bleeding from the terminal artery as it can directly reach the injured vessel. However, when a metallic coil is used to stop the local arterial flow, it can represent a risk of collateral flow to the peripheral side of the coil. In Case 1, coil embolization was selected to avoid non-target embolization with gelatin sponge to the NT of the APhA by backflow of the embolization material. Moreover, because Case 1 was iatrogenic trauma, we had to be careful to not cause any complications. In contrast, in Case 2, a gelatin sponge was used to avoid the collateral vascular supply with proximal embolization with coils. There was a risk of hemorrhage after the procedure due to the diffuse fractures which could cause movement of bone fragments. Therefore, whole embolization of the PT of the APhA was performed. A previous report described the use of n-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA) for embolization of the APhA[16]. NBCA is a liquid-type embolization material that can achieve complete and eternal embolization, so it is preferred when the hemorrhage is severe or life-threatening. However, as non-target embolization could cause cranial nerve paralysis, the application to the APhA must be carefully scrutinized.

The current article is subject to some limitations. The artery of the Rosenmuller fossa could only be identified in Case 1 by Xper CT and angiography. More cases are needed to determine whether this artery can be identified.

This article reports two cases of TAE of the PT of the APhA due to trauma. We identify and propose a new name for the “artery of Rosenmuller fossa.” Although bleeding from the PT of the APhA is rare, radiologists should be aware that the PT of the APhA can cause nasal hemorrhage in patients with trauma. An appropriate embolization material should be selected by considering how the target vessels are distributed, cranial nerve preservation and bleeding severity.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Atanasova EG, Bulgaria; Ferreira GSA, Brazil S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Hacein-Bey L, Daniels DL, Ulmer JL, Mark LP, Smith MM, Strottmann JM, Brown D, Meyer GA, Wackym PA. The ascending pharyngeal artery: branches, anastomoses, and clinical significance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:1246-1256. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Geibprasert S, Pongpech S, Armstrong D, Krings T. Dangerous extracranial-intracranial anastomoses and supply to the cranial nerves: vessels the neurointerventionalist needs to know. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1459-1468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Storck K, Kreiser K, Hauber J, Buchberger AM, Staudenmaier R, Kreutzer K, Bas M. Management and prevention of acute bleedings in the head and neck area with interventional radiology. Head Face Med. 2016;12:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Suzuki T, Sakashita T, Homma A, Hatakeyama H, Kano S, Mizumachi T, Yoshida D, Fujima N, Onimaru R, Tsuchiya K, Yasuda K, Shirato H, Suzuki F, Fukuda S. Effectiveness of superselective intra-arterial chemoradiotherapy targeting retropharyngeal lymph node metastasis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:3331-3336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chen D, Concus AP, Halbach VV, Cheung SW. Epistaxis originating from traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the internal carotid artery: diagnosis and endovascular therapy. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:326-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Paul V, Kupfer Y, Tessler S. Severe epistaxis after nasogastric tube insertion requiring arterial embolisation. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sclafani SJ. The role of angiographic hemostasis in salvage of the injured spleen. Radiology. 1981;141:645-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Masters LT, Nelson PK. Pre-operative Angiography and Embolisation of Petroclival Meningiomas. Interv Neuroradiol. 1998;4:209-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wu AW, Mowry SE, Vinuela F, Abemayor E, Wang MB. Bilateral vascular supply in juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:639-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | White JB, Link MJ, Cloft HJ. Endovascular embolization of paragangliomas: A safe adjuvant to treatment. J Vasc Interv Neurol. 2008;1:37-41. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Pero G, Quilici L, Piano M, Valvassori L, Boccardi E. Onyx embolization of dural arteriovenous fistulas of the cavernous sinus through the superior pharyngeal branch of the ascending pharyngeal artery. J Neurointerv Surg. 2015;7:e16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Luo CB, Teng MM, Chang FC. Radiation acute carotid blowout syndromes of the ascending pharyngeal and internal carotid arteries in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:644-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kurata A, Kitahara T, Miyasaka Y, Ohwada T, Yada K, Kan S. Superselective embolization for severe traumatic epistaxis caused by fracture of the skull base. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1993;14:343-345. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Shibao S, Akiyama T, Ozawa H, Tomita T, Ogawa K, Yoshida K. Descending musculospinal branch of the ascending pharyngeal artery as a feeder of carotid body tumors: Angio-architecture and embryological consideration. J Neuroradiol. 2020;47:187-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lasjaunias P, Moret J. The ascending pharyngeal artery: normal and pathological radioanatomy. Neuroradiology. 1976;11:77-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Luo CB, Teng MM, Chang FC, Chang CY. Transarterial embolization of acute external carotid blowout syndrome with profuse oronasal bleeding by N-butyl-cyanoacrylate. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:702-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |