Published online Nov 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11638

Peer-review started: July 21, 2022

First decision: August 19, 2022

Revised: August 29, 2022

Accepted: October 9, 2022

Article in press: October 9, 2022

Published online: November 6, 2022

Processing time: 97 Days and 15.9 Hours

Primary pancreatic paraganglioma is exceedingly rare. Most patients with pan

A 26-year-old female patient was admitted to the hospital with unexplained abdominal pain. Dual-layer spectral-detector computed tomography (DLCT) revealed a mixed density mass in the pancreatic body and tail. The patient was transferred to our hospital after previous failed surgical resection at other hos

The rare malignant pancreatic paraganglioma reported here was difficult to diagnose preoperatively. Early filling of the draining vein may be a crucial diagnostic imaging feature. DLCT can provide more precise information for surgical resection through dual-energy imaging.

Core Tip: Primary pancreatic paraganglioma is an exceedingly rare, generally benign tumor, with only four cases of malignancy reported. They are often misdiagnosed as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs). Early filling of the draining veins may be a crucial imaging feature to differentiate pancreatic paraganglioma from pNETs and may be observed more frequently in malignant cases. Surgical resection is the primary treatment modality. However, the rich vascularity and potential functionality of the tumor pose a significant risk for invasive surgery. Thorough preoperative evaluation and preparation are necessary. Definitive diagnosis relies primarily on histopathological examination.

- Citation: Li T, Yi RQ, Xie G, Wang DN, Ren YT, Li K. Pancreatic paraganglioma with multiple lymph node metastases found by spectral computed tomography: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(31): 11638-11645

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i31/11638.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11638

Paraganglioma originates from neural crest cells in the sympathetic or parasympathetic ganglia and is a rare neuroendocrine tumor with an incidence of approximately 2-8 per 1 million people per year[1]. Paragangliomas arising in the pancreas are even rarer, with an average age of onset of 52 years, and most of these tumors are nonfunctional[2]. The malignancy rate of paragangliomas is approximately 10%-50%[3]. Patients often lack a typical clinical presentation, especially those with nonfunctional paragangliomas, and the imaging features of these tumors are similar to those of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs), making the preoperative diagnosis very difficult. Herein, we report a malignant pancreatic paraganglioma in a young person. We discuss the imaging features and clinical characteristics of the tumor and review the relevant literature.

A 26-year-old female patient complained of epigastric pain for 2 years.

This patient had frequent epigastric pain accompanied by posterior back pain starting 2 years prior, which could not be relieved by changing positions. A pancreatic mass was found at a local medical institution, and a frozen tissue biopsy revealed a possible rhabdomyosarcoma. The mass was assessed as unresectable, and the operation was halted. The patient was then transferred to a higher tier hospital for treatment, where the previous biopsy was retrieved, with the diagnosis of mucinous spindle cell soft tissue tumor favored. The patient was discharged after receiving chemotherapy (paclitaxel liposome + nedaplatin four times), radiotherapy (25 d), targeted therapy (anlotinib), and immunotherapy (toripalimab), which produced no significant effect, and the above therapeutic measures were discontinued after more than 1 year.

The patient previously had elevated blood glucose levels up to 21 mmol/L and was not receiving regular treatment. She denied hypertension or other medical histories.

The patient had no history of alcohol or tobacco abuse. There was no obvious abnormality in her family history.

There was no obvious abnormality in the physical examination. The patient’s abdomen was soft, without tenderness or a palpable mass.

Laboratory examinations showed that the patient's fasting glucose and antithyroid peroxidase antibody (TPO-Ab) levels were 9.03 mmol/L and 359.88 IU/mL, respectively, on admission. The serum tumor markers were within the normal ranges. There was no plasma/urine levels of fractioned metanephrines and catecholamines measured.

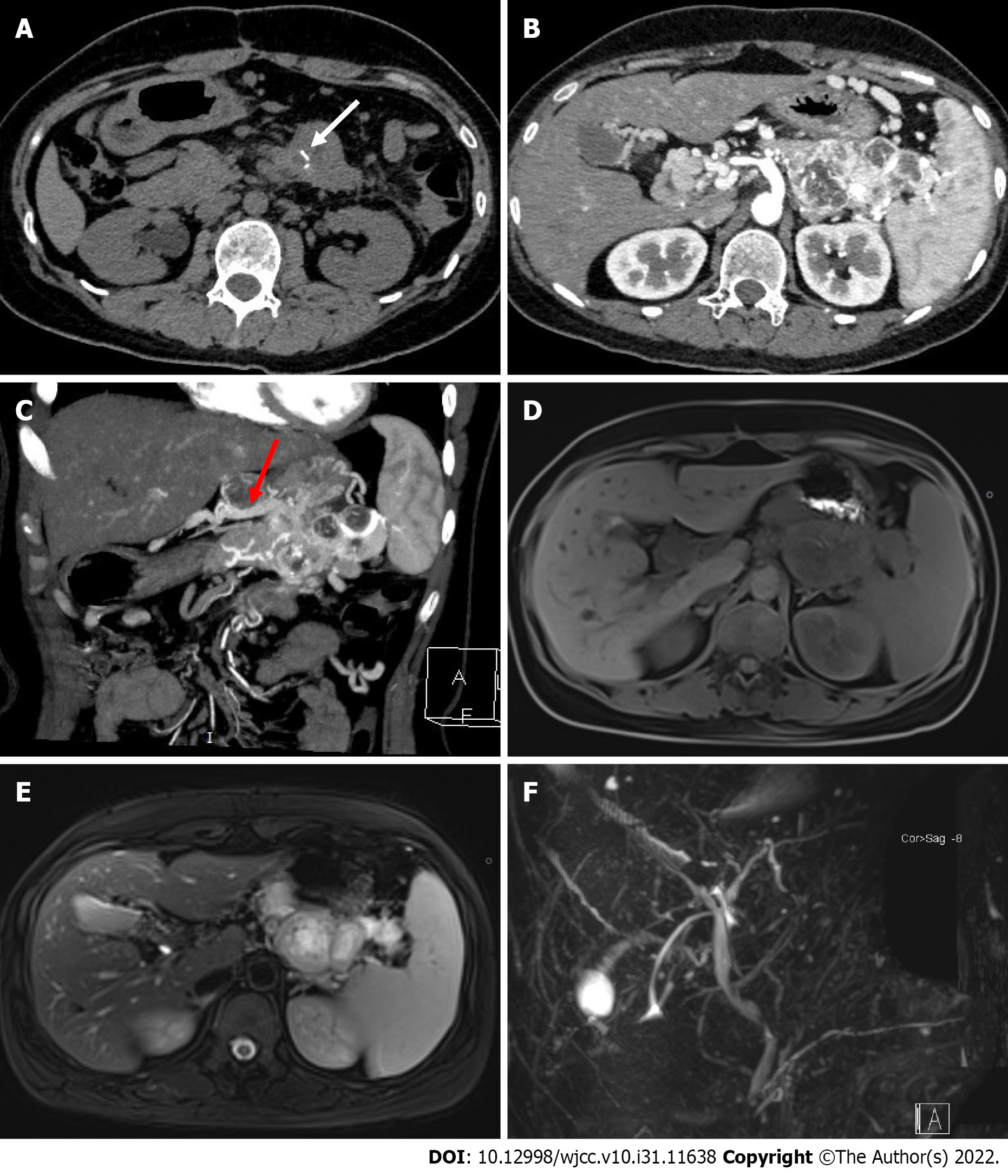

Abdominal dual-layer spectral-detector computed tomography (DLCT) showed a mixed density mass in the pancreatic body and tail, measuring approximately 7.1 cm × 5.7 cm × 3.7 cm, with indistinct borders and short streaks of calcification within the mass (Figure 1A). The contrast-enhanced scans (Figure 1B) showed significant mass enhancement, especially in the arterial phase, and patchy hypointense areas were observed within the mass. The peritumor and intratumor vessels were ab

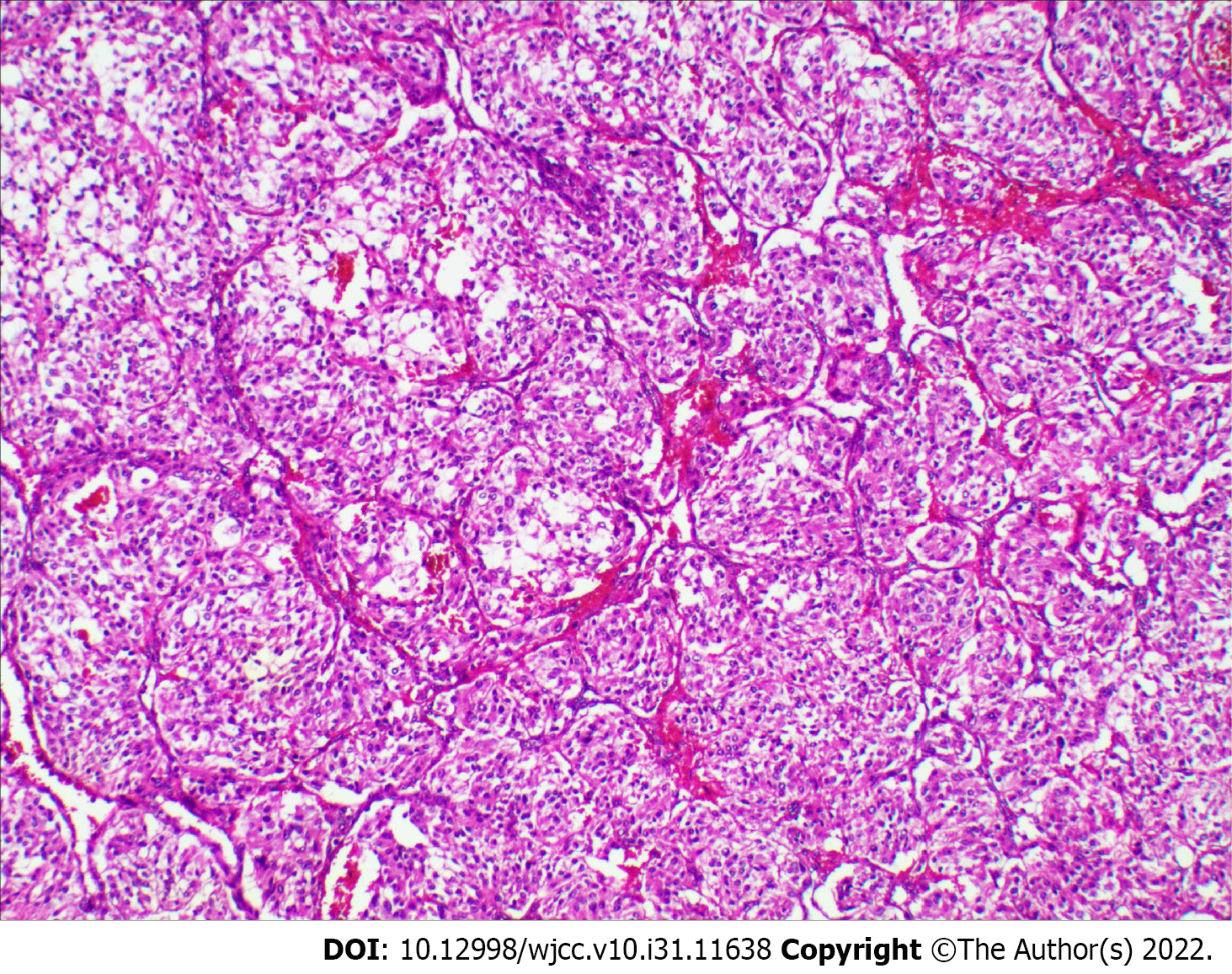

Postoperative pathology uncovered a solid gray-white mass measuring approximately 8 cm × 5 cm × 4 cm. Histological examination revealed a tumor consisting of well-defined nests of polygonal cells separated by vascular fiber septa, forming a classic Zellballen pattern (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry showed positivity for chromogranin A, synaptophysin, as well as sustentacular cells expressing S-100 protein. The Ki-67 index was 8%. Staining for cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen was negative. Therefore, based on a combination of the histology and immunohistochemistry results, the final diagnosis was malignant pancreatic paraganglioma, with tumor metastases in the peripancreatic lymph nodes (4/6) and no metastases in the excisional margin or spleen.

Based on the imaging findings, the patient underwent pancreatic body-tail resection, total splenectomy, and radical lymph node dissection. A large and solid tumor originating from the pancreatic body-tail was found during surgery. The long diameter of the tumor was approximately 8 cm, the mass was adherent to the stomach's posterior wall, and the lower portion of the tumor was located in the mesentery of the transverse colon and to the left of the superior mesenteric artery. A hard lymph node of approximately 3.5 cm in diameter was found near the lesser curvature of the stomach. The patient's blood pressure levels and heart rates were not significantly altered during the procedures.

The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit after surgery and was discharged in good condition 2 wk later; she did not receive follow-up adjuvant therapy. The patients' blood glucose levels and TPO-Ab levels failed to return to normal.

Paraganglioma is a rare tumor that originates from neural crest cells. This tumor usually occurs in the head, neck, and retroperitoneum, and paragangliomas in the pancreas are rare[4]. Malignancy is even rarer, with only four cases reported to date (Table 1)[5-8], including three patients who showed lymph node metastases and one patient with multiple liver metastases. Currently, the presence of invasion into vascular and peripheral structures or metastasis is a reliable basis for diagnosing malignant paraganglioma[9]. We report a malignant nonfunctional paraganglioma in the pancreas with lymph node metastasis, the second such case in a young patient.

| Ref. | Year | Age | Sex | Siez (cm) | Location | CT or MRI manifestations | Function | Treatment | Metastasis | Draining vessels |

| Higa et al[5] | 2012 | 65 | F | 2.0 | Head | CT: A mass with mixed attenuation and areas of enhancement | No | PD | Lymph node | NE |

| AI-Jiffry et al[6] | 2013 | 19 | F | 9.0 × 5.0 × 9.5 | Head | CT: A mass showed peripheral enhancement with a relatively central hypodense pattern andabundant vascularity | Yes | PD | Lymph node | Present |

| Zhang et al[7] | 2014 | 50 | F | 6.0 | Head | CT: A solid well-vascularized tumor, with multiple liver metastases | Yes | Operation halted | Liver | NE |

| Jiang et al[8] | 2021 | 41 | M | 4.1 × 4.2 | Body | CT: A solid, heterogeneous soft tissue dense tumor, with marked enhancement during the arterial phase and the venous phase | No | DP | Lymph node | Present |

| Present case | 2022 | 26 | F | 8.0 × 5.0 × 4.0 | Body-tail | CT: A highly vascular and poor-defined mass, with remarkable enhancement in the arterial phase, a low-intensity lesion on T1-weighted images and a high-intensity lesion on T2-weighted images | No | CP | Lymph node | Present |

Patients with paragangliomas of the pancreas usually lack specific clinical manifestations. Patients with nonfunctional paragangliomas often have no obvious symptoms or present with unexplained epigastric pain, and such tumors are mostly found incidentally during imaging examinations. Due to elevated catecholamine levels, patients with functional paragangliomas may have hypertension, headache, sweating, and palpitations[10]. However, these manifestations are easily overlooked by clinicians, and the presence of a functional tumor is often realized only when a rapid increase in blood pressure and heart rate occurs during surgery. Due to the mass's rich vascularity and potential functionality, blind invasive investigations and procedures may result in catastrophic complications or surgical failure. For instance, a patient[7] with pancreatic paraganglioma had a sudden rise in blood pressure to 220 mmHg during surgery. The operation had to be stopped because of inadequate preoperative preparation. Another patient[11] was preoperatively misdiagnosed with pancreatic cancer. After touching the tumor intraoperatively, the patient's systolic blood pressure suddenly rose to 180 mmHg, and her heart rate reached 140 beats per minute. As a result, the operation was stopped, and the patient died from cardiac failure 34 h after the operation. These cases indicate that the relevant laboratory tests performed before surgery must be improved to prevent failed surgeries and death due to functional tumors and inadequate preoperative preparation. Meta-iodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) nuclear imaging and measurement of metanephrines in blood or urine can effectively differentiate between functional and nonfunctional paragangliomas[12].

Imaging examinations are an essential method for diagnosing and evaluating pancreatic paraganglioma. The parenchymal portion of the mass shows low-intensity on T1W1 and hyperintensity on T2WI[13]. CT scans usually show a solid or cystic soft tissue mass, most often located in the pancreatic head, with some calcifications visible. The mass is heterogeneously enhanced with necrosis and cystic changes in the arterial phase and persistently enhanced in the portal and venous phases, with abundant peritumoral and intratumoral vessels. Although the head of the pancreas is the most common site of pancreatic paraganglioma and the tumor is usually large, there is no significant dilatation of the bile duct and pancreatic duct. In a few cases, the pancreatic duct is mildly dilated[14-18]. Pancreatic cancer often presents as a hypoenhancing mass in the pancreatic head with significant dilation of the pancreatic and bile ducts, which allows the differentiation of pancreatic paragangliomas from pancreatic cancer. Patients with pancreatic paragangliomas usually do not have elevated serum tumor markers. Because of the similar imaging presentations, it is difficult to distinguish paragangliomas from pNETs; however, it has been reported[15,18] that paragangliomas often present with early filling of the draining veins, and in 50% of evaluable cases, the draining veins can be observed. In our case, we also found a large number of draining veins. Moreover, this sign seems to be more visible in malignant cases. Early filling of the draining veins has been observed in all evaluable malignant cases (Table 1). This sign may be a vital imaging feature for diagnosing pancreatic paraganglioma.

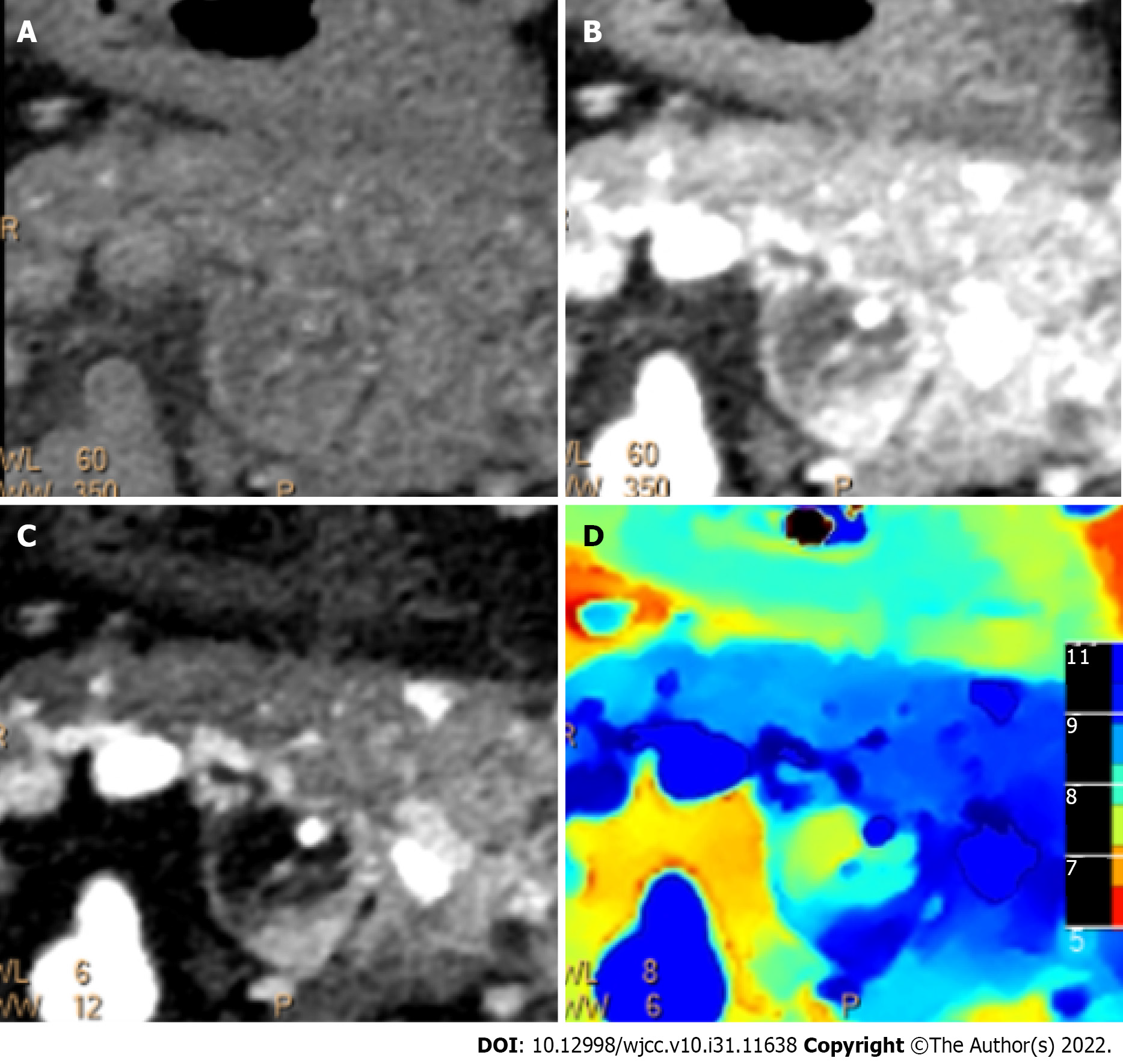

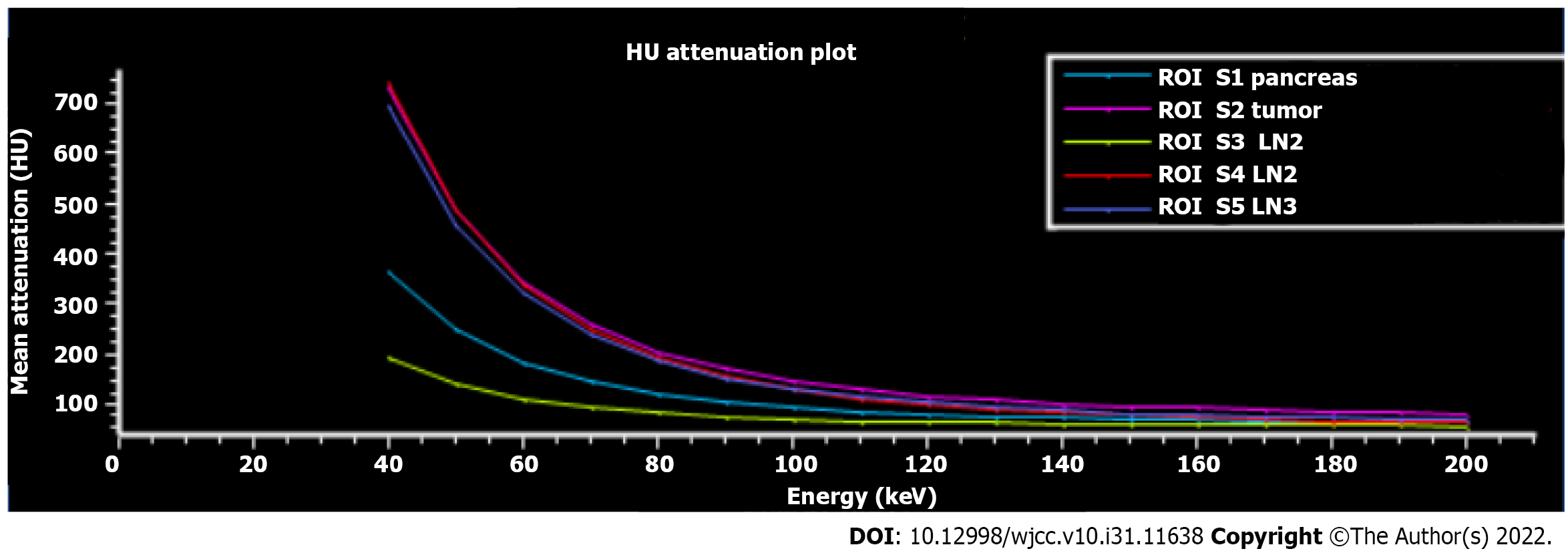

Although it is difficult to differentiate pancreatic paragangliomas from pNETs accurately, surgical treatment is the preferred treatment for both. Therefore, preoperative assessments of tumor size, degree of invasion, and relationship with surrounding blood vessels and adjacent organs are more important. CT is currently the main imaging examination for pancreatic tumor evaluation. DLCT can separate X-ray photons into two energy levels during the detector readout, enabling the generation of both conventional CT images and images based on dual-energy processing[19]. When using DLCT, typical reconstructed image sets include virtual monoenergetic images at varying energy levels, effective atomic number maps, and material-decomposition images (e.g., maps of water and iodine content). Therefore, DLCT can provide information beyond conventional CT analysis[20]. We performed a comprehensive imaging evaluation of the lesion using DLCT. Based on the powerful advantages of dual-energy imaging and multiparametric imaging, we more accurately assessed the boundary of the lesion, the distribution of the surrounding vessels, and the presence of lymph node metastasis. Moreover, we graphed the Hounsfield unit attenuation plot of the surrounding lymph nodes and mass and assessed lymph node metastasis according to the slope (Figure 4). Surgical excision is the primary treatment modality. The surgical approach for pancreatic paraganglioma depends on the tumor's location, including pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) or pylorus-preserving PD (PPPD) for tumors in the pancreatic head or uncinate and local resection or distal pancreatectomy for tumors located in the pancreatic body or tail. In our case, the patient was relatively young, and the tumor was situated on the pancreatic body-tail. To preserve the function of the pancreas, central pancreatectomy was chosen. Regarding cases of pancreatic paraganglioma with metastases, Al-Jiffry et al[6] advocates for postoperative radiation therapy, with I131-MIBG radiation therapy being the method of choice. A large multicenter prospective study[21] showed that high-specific-activity 131I-MIBG had a long-lasting antitumor effect in 22% of patients with advanced paraganglioma.

We have reported a primary malignant paraganglioma of the pancreas, the second such case in a young patient. Draining veins may be a vital imaging sign for diagnosing pancreatic paraganglioma, and surgical resection is the primary treatment modality for these tumors. Comprehensive preoperative imaging evaluations and adequate preoperative preparation are critical, and dual-energy imaging, such as DLCT, can provide more precise information about the lesion before surgical resection.

We would like to thank the staff of the Department of Pathology, Chongqing General Hospital for preparing the histopathological figures and interpretation.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Saito H, Japan; Wang BG, United States S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Abbasi A, Wakeman KM, Pillarisetty VG. Pancreatic paraganglioma mimicking pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. Rare Tumors. 2020;12:2036361320982799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lanke G, Stewart JM, Lee JH. Pancreatic paraganglioma diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:6322-6331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lin S, Peng L, Huang S, Li Y, Xiao W. Primary pancreatic paraganglioma: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tumuluru S, Mellnick V, Doyle M, Goyal B. Pancreatic Paraganglioma: A Case Report. Case Rep Pancreat Cancer. 2016;2:79-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Higa B, Kapur U. Malignant paraganglioma of the pancreas. Pathology. 2012;44:53-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Al-Jiffry BO, Alnemary Y, Khayat SH, Haiba M, Hatem M. Malignant extra-adrenal pancreatic paraganglioma: case report and literature review. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhang L, Liao Q, Hu Y, Zhao Y. Paraganglioma of the pancreas: a potentially functional and malignant tumor. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jiang CN, Cheng X, Shan J, Yang M, Xiao YQ. Primary pancreatic paraganglioma harboring lymph node metastasis: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:8071-8081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Strong VE, Kennedy T, Al-Ahmadie H, Tang L, Coleman J, Fong Y, Brennan M, Ghossein RA. Prognostic indicators of malignancy in adrenal pheochromocytomas: clinical, histopathologic, and cell cycle/apoptosis gene expression analysis. Surgery. 2008;143:759-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lack EE, Cubilla AL, Woodruff JM, Lieberman PH. Extra-adrenal paragangliomas of the retroperitoneum: A clinicopathologic study of 12 tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1980;4:109-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang ZL, Fu L, Zhang Y, Babu SR, Tian B. An asymptomatic pheochromocytoma originating from the tail of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2012;41:165-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | van Gils AP, Falke TH, van Erkel AR, Arndt JW, Sandler MP, van der Mey AG, Hoogma RP. MR imaging and MIBG scintigraphy of pheochromocytomas and extraadrenal functioning paragangliomas. Radiographics. 1991;11:37-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Lee KY, Oh YW, Noh HJ, Lee YJ, Yong HS, Kang EY, Kim KA, Lee NJ. Extraadrenal paragangliomas of the body: imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:492-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ohkawara T, Naruse H, Takeda H, Asaka M. Primary paraganglioma of the head of pancreas: contribution of combinatorial image analyses to the diagnosis of disease. Intern Med. 2005;44:1195-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim SY, Byun JH, Choi G, Yu E, Choi EK, Park SH, Lee MG. A case of primary paraganglioma that arose in the pancreas: the Color Doppler ultrasonography and dynamic CT features. Korean J Radiol. 2008;9 Suppl:S18-S21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | He J, Zhao F, Li H, Zhou K, Zhu B. Pancreatic paraganglioma: A case report of CT manifestations and literature review. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2011;1:41-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Meng L, Wang J, Fang SH. Primary pancreatic paraganglioma: a report of two cases and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1036-1039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Misumi Y, Fujisawa T, Hashimoto H, Kagawa K, Noie T, Chiba H, Horiuchi H, Harihara Y, Matsuhashi N. Pancreatic paraganglioma with draining vessels. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9442-9447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | McCollough CH, Leng S, Yu L, Fletcher JG. Dual- and Multi-Energy CT: Principles, Technical Approaches, and Clinical Applications. Radiology. 2015;276:637-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 790] [Cited by in RCA: 1074] [Article Influence: 107.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Goo HW, Goo JM. Dual-Energy CT: New Horizon in Medical Imaging. Korean J Radiol. 2017;18:555-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pryma DA, Chin BB, Noto RB, Dillon JS, Perkins S, Solnes L, Kostakoglu L, Serafini AN, Pampaloni MH, Jensen J, Armor T, Lin T, White T, Stambler N, Apfel S, DiPippo VA, Mahmood S, Wong V, Jimenez C. Efficacy and Safety of High-Specific-Activity 131I-MIBG Therapy in Patients with Advanced Pheochromocytoma or Paraganglioma. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:623-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |