Published online Nov 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11585

Peer-review started: June 27, 2022

First decision: September 5, 2022

Revised: September 14, 2022

Accepted: October 9, 2022

Article in press: October 9, 2022

Published online: November 6, 2022

Processing time: 122 Days and 1.7 Hours

Porokeratosis (PK) is a common autosomal dominant chronic progressive dyskeratosis with various clinical manifestations. Based on clinical manifestations, porokeratosis can be classified as porokeratosis of mibelli, disseminated super

Linear porokeratosis is a rare PK. The patient presented with unilateral ker

From this case we take-away that LP is a rare disease, by the dermoscopic we can identify it.

Core Tip: We report a case of unilateral linear porokeratosis. Porokeratosis is a common autosomal dominant chronic progressive dyskeratosis with a variety ofvarious clinical manifestations. Dermatoscopy plays an important role in the differential diagnosis of a various diseases and has been widely used in clinical practice because it is noninvasive, simple, and quick. Our patient was diagnosed with unilateral linear porokeratosis based on the clinical presentation, typical pathology, and dermoscopy.

- Citation: Yang J, Du YQ, Fang XY, Li B, Xi ZQ, Feng WL. Linear porokeratosis of the foot with dermoscopic manifestations: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(31): 11585-11589

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i31/11585.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11585

Porokeratosis (PK) is an autosomal dominant chronic progressive dyskeratotic skin disease. However, it has also been disseminated without genetic evidence. Heterozygous germline mutations in the mevalonate pathway genes—MVK, PMVK, MVD, and FDPS—have been found in familial and sporadic porokeratosis[1]. The lesions are characterized by marginal dyke-like warty elevations with mild central atrophy, with or without pruritus[2], and the presence of cornoid lamellae on histopathology[3]. Unilateral linear porokeratosis is an extremely rare condition. One case has been reported as follows.

An 8-year-old Chinese boy presented with keratotic papules, which had been present for more than 4 years, on the bottom of his left foot.

Brown keratotic papules appeared on the bottom of the left foot with no obvious cause and gradually increased in size to the entire left sole. Part of the rash fused into a patch; the patient experienced occasional itching; there was no pain or other discomfort; and he had been treated with topical medication (specific details not available) with poor results.

The patient was previously in good health.

Born in Taiyuan City, Shanxi Province, now living in the same place, no history of contact with epidemic areas, regular life; No history of smoking, drinking, exposure to toxic substances, dust and radioactive substances. No family members had similar diseases.

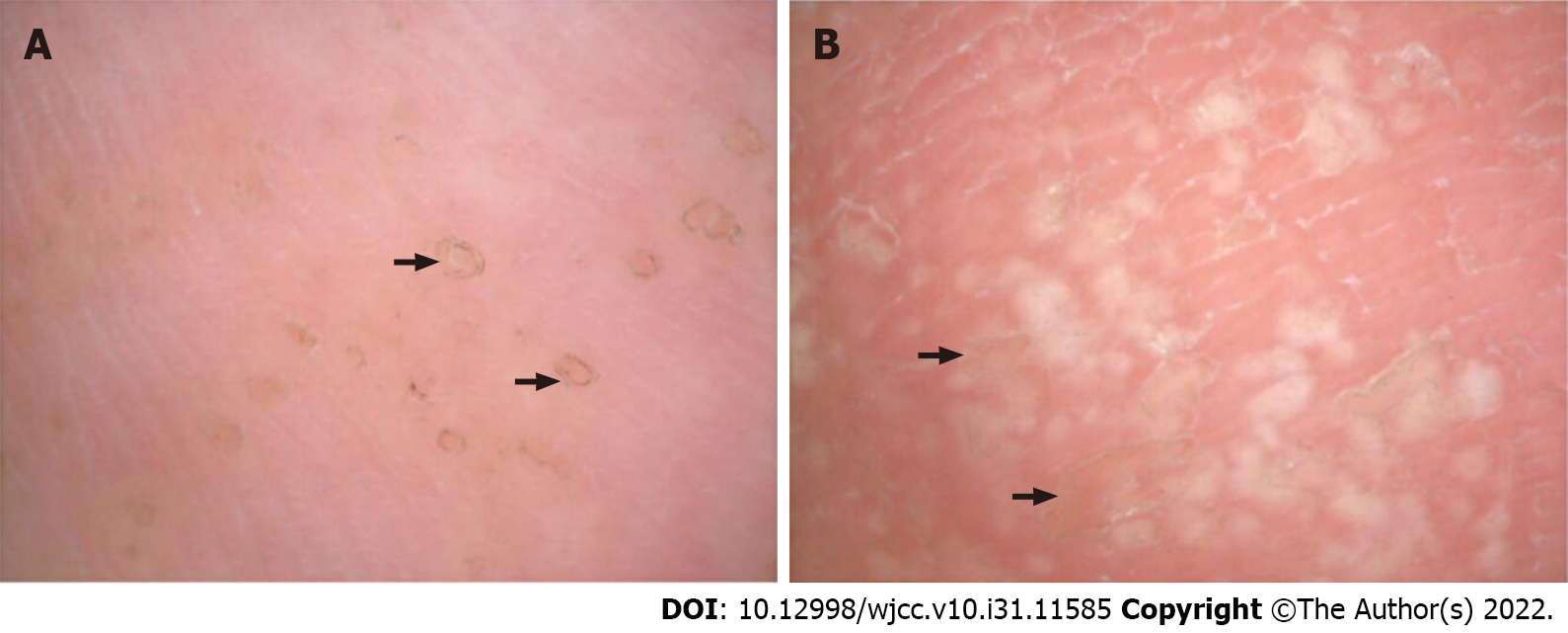

Dermatological examination revealed annular brown keratotic papules on the left plantar, approximately 0.3-0.5 cm in diameter, partially fused, distributed in a Blaschkoid pattern, with a rough surface and well-demarcated borders. The centre of the plaque was slightly atrophic and depressed (Figure 1).

The remainder of the physical examination was normal. For example white blood counts, low-value platelet, alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, blood lipids were normal.

Dermoscopic examinations showed that the rim of the lesions at the bottom of the foot was surrounded by dotted or globular brown pigmented structures or white bands (“white track”). A few dotted or flaky white homogeneous structureless areas were noted in the center of the lesions (scar-like center)[4] (Figure 2).

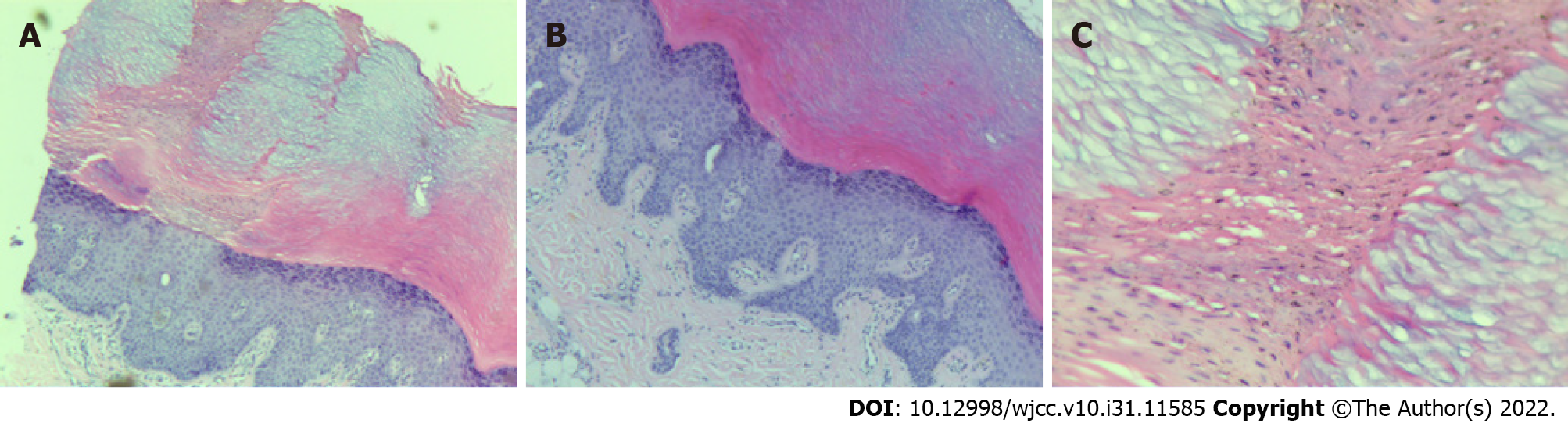

Histopathological examination revealed hyperkeratosis of the epidermis, multiple columns of parakeratotic corneocytes, a reduced or missing granular layer, and a thickened spinous layer. The upper dermis contained a small inflammatory infiltrate mainly composed of lymphocytes (Figure 3).

Unilateral linear porokeratosis.

Avoid friction, liquid nitrogen freezing and 5% salicylic acid ointment.

There were no significant changes in the skin lesions, and the patients reported that the skin lesions were smoother than those before treatment.

Unilateral linear LP is much rarer, with an unknown global incidence rate. Most reports are case reports. A retrospective study on conducted between 2000 and 2010 at the National Skin Centre in Singapore reported that 56% of porokeratosis cases were mibelli, 18% were disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis, 11% were disseminated superficial porokeratosis (DSP), and 13% were LP[5]. A similar retrospective study conducted between 2003 and 2017 by Shanghai Huashan Hospital reported 40% of porokeratosis cases were mibelli, 31% were disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis, 27% were DSP, and 2% were LP[6]. Of the 140 PK patients reported to Shandong University Hospital between 2003 and 2017, only 4 had LP[7].

The lesions of PK are mainly characterized by a central atrophic region surrounded by a dyke-like elevations with microkeratotic spines. The most characteristic pathological changes in all types are a high degree of keratinization at the edge of the dyke, multiple columns of parakeratotic corneocytes, cornoid lamella, thin granular layer, and thick spinous layer.

Dermatoscopy plays an important role in the differential diagnosis of various diseases and has been widely used in clinical practice because it is noninvasive, simple, and quick. For all types of PK, the most characteristic dermoscopic finding is the keratinous striae surrounding the lesions, which are well-defined, thin, white-yellowish, annular peripheral hyperkeratotic structures ("white track"). DSP is often accompanied by hyperpigmentation; the middle of the lesion has white or light brown annular or punctate structures, and sometimes linear or punctate vessels are visible[4]. However, in this case, the site of occurrence was the sole of the foot, and hyperkeratosis was evident; there was no obvious "white track,” but a clear dyke-like margin with a white area in the center of the lesion was visible.

Our patient was diagnosed with unilateral LP based on the clinical presentation, typical pathology, and dermoscopy. The disease usually occurs at birth or in childhood and is autosomal dominant with no gender disparity. Linear lesions usually occur unilaterally along the Blaschko line, most commonly on both lower extremities, then spread to the upper extremities and the trunk[3,8]. Rarely, they present as multiple lesions on the trunk and limbs with a herpes zoster-like distribution[9]. Based on the clinical observations, histopathological findings and dermoscopic features of the patient, the diagnosis was consistent with unilateral LP.

PK must be distinguished from annular lichen planus, lichen sclerosis et atrophicus, verrucous nevus, verrucous carcinoma, Bowen disease, actinic keratosis, elastosis perforans serpiginosa, and ichthyosis linearis circumflera. It is also misdiagnosed as eczema, contact dermatitis, tinea cruris, tuberculosis verucosa cutis, or psoriasis, which can be differentiated by histopathological examination of the skin[3].

On average, 6.9%-30% of PK patients progresses to skin cancer; squamous cell carcinoma is more common with a lower incidence of basal cell carcinoma[10]. Carcinoma is common in larger isolated lesions in pulmonary metastasectomy and lung metastases[11] and should be followed up and examined regularly with histopathological examination if necessary.

Treatment can include topical 5% to 10% salicylic acid ointment and local retinoids (tretinoin 0.025%-0.1%, tazaroten). The rash can be treated with oral retinoids (isotretinoin, etretinate, and acitretin). Patients with aggravated sun exposure can take oral chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine, and those with isolated, smaller lesions can use carbon dioxide laser, electrocautery, liquid nitrogen freezing, or surgical excision[12]. In addition, tacrolimus 0.1% ointment in combination with local steroids can relieve itching symptoms in patients with LP[13]. In our patient, some lesions were treated with liquid nitrogen freezing and 5% salicylic acid ointment, and are currently being followed up.

LP is very rare, and we report a case of childhood onset. Pathological examination and dermoscopy have unique findings and can be used to diagnose the disease.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Dermatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Bugaj AM, Poland; Corvino A, Italy; Khalifa AA, Egypt; Primadhi RA, Indonesia S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Zhang Z, Li C, Wu F, Ma R, Luan J, Yang F, Liu W, Wang L, Zhang S, Liu Y, Gu J, Hua W, Fan M, Peng H, Meng X, Song N, Bi X, Gu C, Zhang Z, Huang Q, Chen L, Xiang L, Xu J, Zheng Z, Jiang Z. Genomic variations of the mevalonate pathway in porokeratosis. Elife. 2015;4:e06322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kanitakis J. Porokeratoses: an update of clinical, aetiopathogenic and therapeutic features. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:533-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nicola A, Magliano J. Dermoscopy of Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:e33-e37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | 4 Errichetti E, Stinco G. Dermoscopy in General Dermatology: A Practical Overview. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6:471-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tan LS, Chong WS. Porokeratosis in Singapore: an Asian perspective. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:e40-e44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gu CY, Zhang CF, Chen LJ, Xiang LH, Zheng ZZ. Clinical analysis and etiology of porokeratosis. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8:737-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fu XA. Clinical features analysis and genetic study of 140 case of porokeratosis. Shandong University, 2019. |

| 8. | Chalmers R, Barker J, Griffiths C, Bleiker T, Creamer D. Rook's textbook of dermatology. John Wiley & Sons, 2008. |

| 9. | Biswas A. Cornoid lamellation revisited: apropos of porokeratosis with emphasis on unusual clinicopathological variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:145-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ahmed A, Hivnor C. A case of genital porokeratosis and review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Silver SG, Crawford RI. Fatal squamous cell carcinoma arising from transplant-associated porokeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:931-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Weidner T, Illing T, Miguel D, Elsner P. Treatment of Porokeratosis: A Systematic Review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:435-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Parks AC, Conner KJ, Armstrong CA. Long-term clearance of linear porokeratosis with tacrolimus, 0.1%, ointment. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:194-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |