Published online Oct 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i29.10614

Peer-review started: April 14, 2022

First decision: July 11, 2022

Revised: July 14, 2022

Accepted: August 30, 2022

Article in press: August 30, 2022

Published online: October 16, 2022

Processing time: 163 Days and 0.9 Hours

The Fontan operation is the only treatment option to change the anatomy of the heart and help improve patients’ hemodynamics. After successful operation, patients typically recover the ability to engage in general physical activity. As a better ventilatory strategy, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) provides gas exchange via an extracorporeal circuit, and is increasingly being used to improve respiratory and circulatory function. After the modified Fontan operation, circulation is different from that of patients who are not subjected to the procedure. This paper describe a successful case using ECMO in curing influenza A infection in a young man, who was diagnosed with Tausing-Bing syndrome and underwent Fontan operation 13 years ago. The special cardiac structure and circulatory characteristics are explored in this case.

We report a successful case using ECMO in curing influenza A infection in a 23-year-old man, who was diagnosed with Tausing-Bing syndrome and underwent Fontan operation 13 years ago. The man was admitted to the intensive care unit with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome as a result of influenza A infection. He was initially treated by veno-venous (VV) ECMO, which was switch

After the modified Fontan operation, circulation is different compared with that of patients who are not subjected to the procedure. There are certainly many differences between them when they receive the treatment of ECMO. Due to the special cardiac structure and circulatory characteristics, an individualized liquid management strategy is necessary and it might be better for them to choose an active circulation support earlier.

Core Tip: After the modified Fontan operation, circulation is different from that of patients who are not subjected to the procedure. In this article, we describe a 23-year-old man, with a history of modified Fontan operation for Tausing-Bing syndrome, who was admitted to the intensive care unit with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome as a result of influenza A infection. The man was initially treated by veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), which was switched to veno-venous-arterial ECMO 5 d later. As circulation and respiratory function gradually improved, the veno-venous-arterial ECMO equipment was successfully removed. Then, the man was discharged from hospital successfully. This case highlights that an individualized liquid management strategy is necessary and it might be better for such patients to choose an active circulation support earlier.

- Citation: Guo HB, Tan JB, Cui YC, Xiong HF, Li CS, Liu YF, Sun Y, Pu L, Xiang P, Zhang M, Hao JJ, Yin NN, Hou XT, Liu JY. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in curing a young man after modified Fontan operation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(29): 10614-10621

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i29/10614.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i29.10614

The Fontan operation is the only treatment option to change the anatomy of the heart and help improve patients’ hemodynamics[1]. The patient’s circulation after the Fontan surgery is different from that of a normal patient. The mortality of patients diagnosed with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) ranges from 17.3% to 41.4% among critically ill patients with H1N1 infection[2,3], and many patients need the help of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Whereas, due to the special circulation after the Fontan surgery, supporting Fontan patients on ECMO carries high morbidity and mortality[4]. Few articles have described the special circulation about cases who receive ECMO after the modified Fontan operation. We herein report such a case.

A 23-year-old male patient presented to the general intensive care unit (ICU) of Beijing Ditan Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University on April 5, 2018 mainly due to fever for 5 d, with 39.1 °C as the highest temperature.

Upon history-taking, the patient revealed that he got a fever with 39.1 °C as the highest temperature on April 1, 2018. He received treatment at a local health clinic, where he was prescribed with cephalosporin antibiotics on April 2, 2018. Then, the patient saw a doctor at Beijing Huairou District Hospital. A chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed large consolidation of the lower lobe of the right lung and superior lobe of the left lung on April 4, 2018. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed: pH 7.476, PCO2 22 mmHg, PO2 54.1 mmHg, and HCO3- 20.4 mmol/L. The fraction of inspiration O2 (FiO2) at the time of taking arterial blood samples was 21%. The antigen of influenza A was positive. Then, he was transferred to the general ICU of Beijing Ditan Hospital Affiliated Capital Medical University for further treatment on April 5, 2018.

At birth, the patient was diagnosed with atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, pulmonary artery stenosis, and right ventricular double outlet, also known as Tausing-Bing syndrome. He received the modified Fontan operation 13 years ago when he was 10 years old. In the surgery, the pulmonary orifice was sutured, and the tricuspid valve was sewn closed, then the left auricle was connected with the pulmonary artery to ensure stable cardiopulmonary circulation during the operation. He recovered well and was able to perform general physical activity easily by himself after the operation. Three years ago, echocardiography at the regular visit revealed a double outlet in the right ventricle. Moreover, it was also observed that he showed right atrial enlargement and aortic valve regurgitation. The ejection fraction of the young man was 50%.

The patient had no previous or family history of similar illnesses.

The physical examination revealed the following: Temperature 38.4 °C, blood pressure 86/54 mmHg, respiration rate 40 times/min, pulse rate 110 times/min, and SPO2 80%. The breath sounds of both lungs were thick and moist rales can be easily heard. Arrhythmia and dropped-beat pulse were found in the physical examination. Due to respiratory failure and septic shock, his skin was wet, cold, and bluish.

Laboratory tests at the time of admission to the ICU were as follows: White blood cell count: 11.89 × 109/L (reference range, 4-10 × 109/L); neutrophil percentage: 84.94% (reference range, 50%-70%); hemoglobin: 173.10 g/L (reference range, 110-150 g/L); hematocrit: 48.70% (reference range, 35%-45%); platelet count: 178.00 × 109/L (reference range, 100-300 × 109/L); sodium: 128.5 mmol/L (reference range, 137-147 mmol/L); creatinine 279.6 µmol/L (reference range, 41-73 µmol/L); procalcitonin: 4.51 ng/mL (reference range, < 0.05 ng/mL); C-reactive protein: 212.9 mg/L (reference range, 0-5 ng/mL); alanine aminotransferase 48.6 U/L (reference range, 7-40 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase: 100.4 U/L (reference range, 13-35 U/L); total bilirubin: 26.2 µmol/L (reference range, 0-18.8 µmol/L); direct bilirubin: 21.4 µmol/L (reference range, 0-6.8 µmol/L).

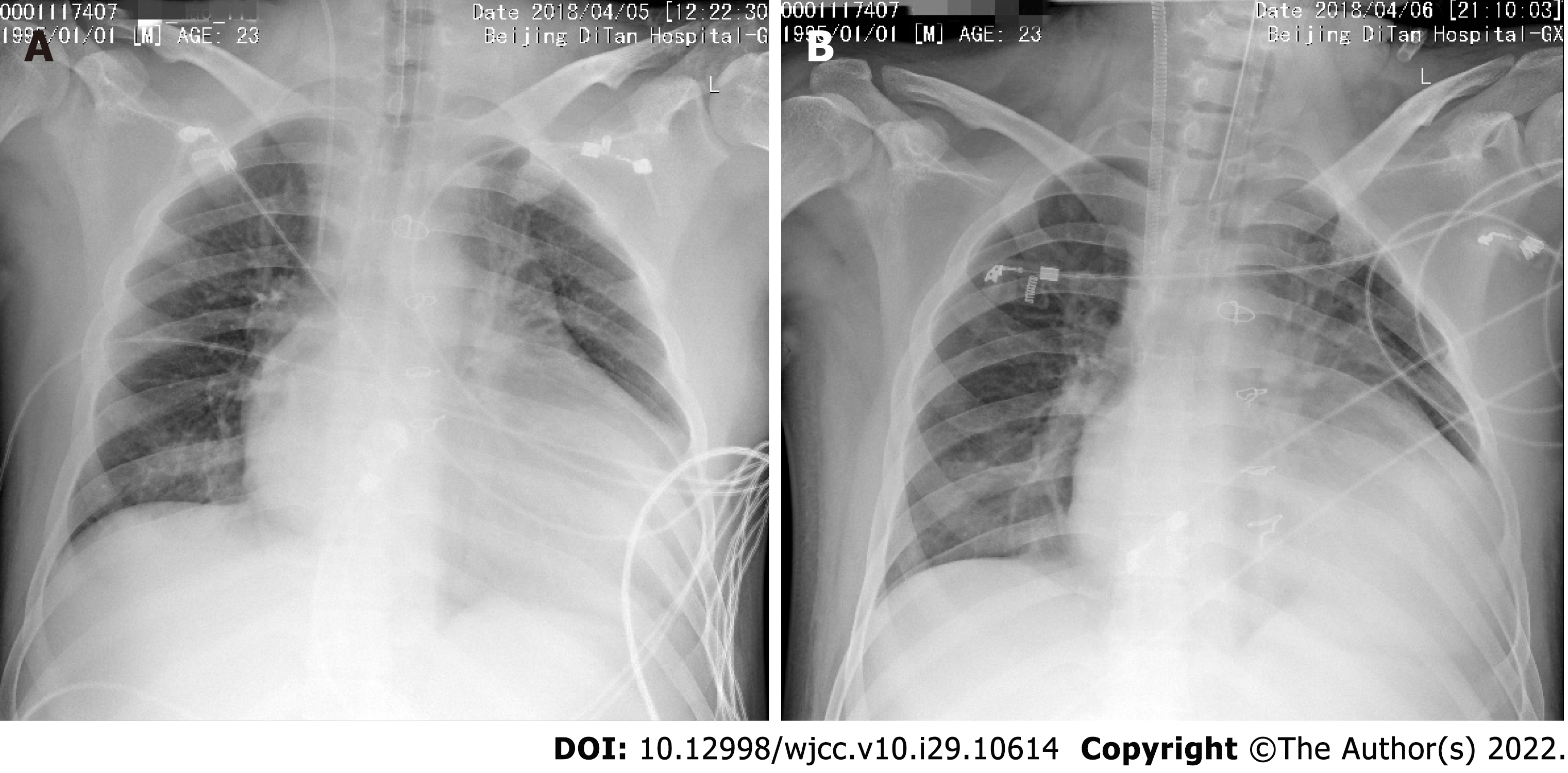

The chest X-ray of the patient on admission is shown in Figure 1A. The chest X-ray of the patient at the first day of his receiving the veno-venous (VV) ECMO therapy is shown in Figure 1B.

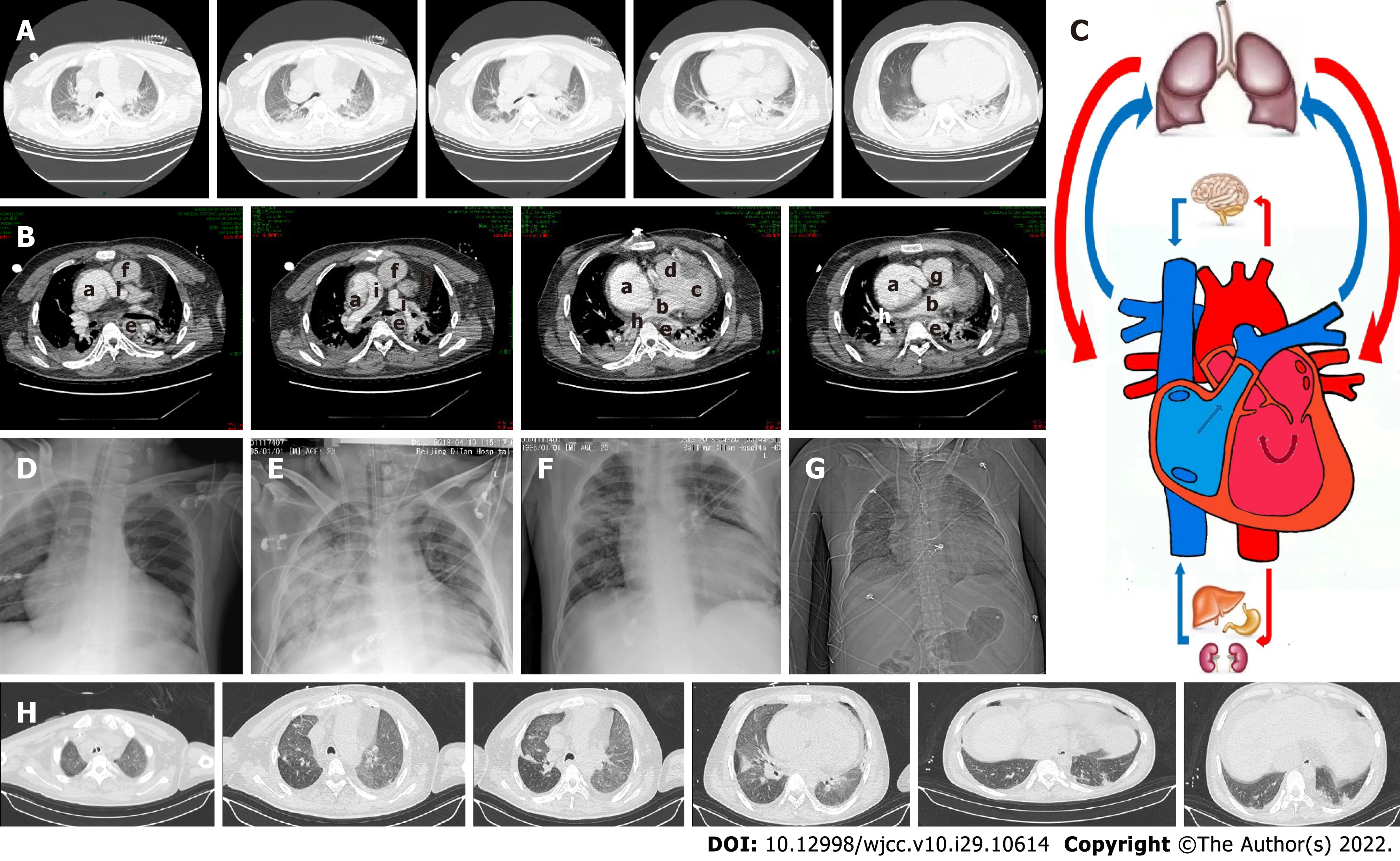

Enhanced chest CT was performed on April 9, 2018 (Figure 2A and B), which revealed postoperative changes of the heart and bilateral pneumonia changes. A small amount of bilateral pleural effusion was also detected. The direction of blood flow is shown in Figure 2C. The chest X-ray of the patient at the second day and ninth day of his receiving the veno-venous-arterial (VVA ECMO) therapy is, respectively, shown in Figure 2D and E. The chest X-ray before the patient finished the VVA ECMO therapy is shown in Figure 2F. The chest X-ray and lung CT images on May 24, 2018 are shown in Figure 2G and H, respectively.

The patient was mainly diagnosed with type A influenza. Other diagnoses were pulmonary infection, severe respiratory failure, acute kidney injury, acute hepatic injury, electrolyte disturbance, and atrial fibrillation.

Upon admission into the ICU, the patient’s APACHE II and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment scores were, respectively, 22 and 10. A Venturi mask was used for supporting respiratory function, and the oxygen flow volume was 15 L/min. The saturation of pulse oxygen of the patient was 80%. Meanwhile, he had difficulty in breathing and breathed 40 breaths per minute. The arterial blood gas analysis before mechanical ventilation indicated the following: pH 7.45, PCO2 30 mmHg, and PO2 48.2 mmHg. Due to severe ARDS, the young patient was intubated on April 5, 2018, and the ventilator mode was intermittent positive pressure ventilation. Other parameters were as follows: FiO2 100%, tidal volume 560 mL, respiratory frequency 20 times/min, positive end-expiratory pressure = 10 cmH2O, and peak airway pressure 23 cm H2O. Moxifloxacin hydrochloride and paramivir were used to combat infection when the patient was admitted to the ICU. Anti-infective drugs were switched to cefoperazone-sulbactam sodium and vancomycin hydrochloride on April 9, 2018. To control a fungal infection, voriconazole was used on April 9, 2018.

Due to the special heart structure after the modified Fontan operation, the central venous pressure (CVP) of the young man was 40 mmHg on admission. As a result of septic shock, noradrenaline was used to raise blood pressure. For severe AKI, hyperkalemia, and metabolic acidosis, continuous renal replacement therapy was initiated when the patient was admitted to the ICU. Even if the protective lung ventilation strategy and ventilation in prone position were properly conducted after mechanical ventilation, his respiratory failure was persistent and did not significantly improve. The arterial blood gas analysis revealed the following: pH 7.193, PCO2 48 mmHg, PO2 52 mmHg, base excess -10 mmol/L, and lactate 1.34 mmol/L. VV ECMO was applied to correct the respiratory failure on April 6, 2018. The two vein indwelling catheters were established, respectively, in the left femoral and right internal jugular veins. The initial parameters of VV ECMO were as follows: Rotation speed 3100 turns/min, blood flow volume 4.3 L/min, oxygen flow volume 4.5 L/min, and FiO2 100%.

As an attempt to ameliorate severe heart failure and cardiogenic shock, the VV ECMO procedure was replaced by VVA ECMO on April 11, 2018. The patient’s right femoral artery was punctured and intubated as the infusion tube, and combined deep venous catheters inserted in the left femoral vein and right internal jugular vein were used as the drainage tube. The initial parameters of VVA ECMO were as follows: Rotation speed 3800 turns/min, blood flow volume 4 L/min, oxygen flow volume 4 L/min, and FiO2 100%. We tried to use negative liquid equilibrium to improve the left heart failure at the early stage of VVA ECMO. The negative fluid balance at the first and second day was, respectively, 272 and 345 mL. As a result, the CVP of the young man decreased to 28 mmHg and his circulation tended to deteriorate. In order to maintain his circulation, the dose of noradrenaline had to adjust from 0.7 to 1.4 ug/kg/min. Then we tried to change the liquid management strategy. The cumulative positive balance was 10000 mL in the following 7 d. His CVP gradually increased to 35 mmHg and the dose of noradrenaline was gradually tapered until stopped on April 20, 2018. The oxygenator and circulation line of ECMO were replaced as the equipment had achieved its design life on April 23, 2018. As ventilator weaning was difficult in a short period for the patient, tracheotomy was operated on April 27, 2018. As circulation and respiratory function gradually improved, VVA ECMO equipment was removed on May 1, 2018.

The patient was successfully withdrawn from artificial ventilation on May 28, 2018 and then discharged from hospital on May 30, 2018. We followed him at his home on October 25, 2021, and he can take care of himself in daily life and engage in light manual labor.

As research reported in 2005, double outlet right ventricle (DORV) occurs in 0.09 cases per 1000 live births. As a rare congenital heart disease, the Tausing-Bing anomaly is the third most common type of DORV[5]. So far, the Fontan operation was the only treatment option to change the anatomy of the heart and help improve patients’ hemodynamics[1]. After successful operation, patients typically recover the ability to engage in general physical activity. H1N1 influenza has a higher case fatality among younger patients and the potential for fulminant ARDS[6]. The mortality of patients diagnosed with ARDS ranges from 17.3% to 41.4% among critically ill patients with H1N1 infection[2,3]. As a better ventilatory strategy, as well as an alternative mode of respiratory support, ECMO provides gas exchange via an extracorporeal circuit, and is increasingly being used to improve respiratory and circulatory function[7]. ECMO is usually used to help patients get through postoperative difficulties such as heart failure and hemodynamically unstable and refractory arrhythmias. As the morbidity and mortality associated with ECMO are relatively high, the survival of children with heart disease that need ECMO support is only 33%-60%[8].

By analyzing the medical history and imaging manifestations, we concluded the direction of blood flow in this case (Figure 2C): Right atrium, pulmonary artery, pulmonary vein, left atrium, left ventricle, right ventricle, aorta, and right atrium. By analyzing data from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization, we found that only 35% of cardiac failure patients subjected to Fontan operation survived to hospital discharge[4]. By analyzing the medical history and imaging results of the patient, there were mainly three factors causing the severe respiratory failure. First, due to the special physiological structure after the operation of Fontan, a single ventricle was more vulnerable to suffering severe left heart failure compared with a normal heart. Furthermore, pulmonary edema caused by the acute left ventricular failure was one of the reasons for respiratory failure. Second, the pulmonary infection caused by H1N1 influenza affected his respiratory function. Thus, severe ARDS might be the second cause of severe respiratory failure. Third, pulmonary arterial hypertension might aggravate systemic circulation congestion and lead to left ventricular preload insufficiency.

The patient’s circulation after the Fontan surgery was different than that of a normal patient. Therefore, supporting Fontan patients on ECMO carries high morbidity and mortality[4]. After the Fontan operation, pulmonary and systemic circulation are mainly sustained by the single ventricle. A study found that patients for whom the Fontan operation was not successful usually suffered anatomic obstruction to flow, pulmonary vascular remodeling, atrioventricular valve dysfunction, univentricular diastolic dysfunction and chronic underfilling, and/or univentricular systolic dysfunction[9]. There are three stages of failure in a Fontan patient, each of which is associated with certain underlying etiologies[10]. Early Fontan failure is often marked by anatomic obstruction. Most patients usually have an early acute onset of failure, prior to end organ injury[11]. Patients with middle and late phase Fontan failure usually exhibit signs of end organ damage. Late phase failure patients present protein losing enteropathy, plastic bronchitis, cirrhosis, or renal failure in the process of medical treatment[12]. In this case, after the Fontan operation, the right atrium of the patient was directly linked with the pulmonary artery. The CVP of the patient at admission to the ICU was 40 mmHg, therefore he was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension. As his circulation depended on the single ventricle, severe sepsis accelerated the process of heart failure. At the beginning of treatment, it was hard to improve the systemic and pulmonary circulation congestion.

Relevant research noted that about 30% of Fontan patients suffered from heart failure in 20 years[13,14]. Patients with neurologic complications, surgical bleeding, and renal failure were inclined to have a higher mortality during the course of ECMO, indicating that ECMO complications may limit survival outcomes for these patients[4]. The patient initially received VV ECMO treatment for severe respiratory failure on April 6, 2018. Even though the man’s respiratory function significantly improved with the help of VV ECMO, shock persisted and did not effectively relieve. By analyzing the pathophysiological characteristics of his heart anatomical structure, we concluded that severe left heart failure might explain the refractory shock. Then, in response to severe heart failure and cardiogenic shock, the VV ECMO was converted to VVA ECMO. The shock was significantly improved with the help of VVA ECMO. Vasoactive drugs were disused in 1 d after the mode of the machine was switched.

We tried to use negative liquid equilibrium to improve the left heart failure at the early stages of VVA ECMO, but failed. The negative liquid equilibrium was smoothly conducted 3 d after the mode of ECMO was changed. As pulmonary pressure of the case was high, the right ventricular ejection depended on pressure differences and needed a higher volume. With the improvement of cardiac function and oxygen, heart and respiratory failures were effectively improved. Meanwhile, pulmonary arterial hypertension declined to some extent, making negative liquid equilibrium a feasible option. In the case, the proper CVP might be 35 mmHg. We had to search a suitable liquid state to balance both the respiratory and circulatory systems. Therefore, an individualized liquid management strategy was necessary.

With the help of VVA ECMO, heart failure and shock were gradually improved. After about 20 d of circulation support, the patient successfully had the VVA ECMO equipment removed. Due to the special cardiac structure and circulatory characteristics, it might be better for him to choose an active circulation support earlier. Other modes such as VAV ECMO might be another choice, especially for those who have a risk of different hypoxia, in which cardiac recovery precedes lung recovery[15]. For this case, VAV ECMO would provide the right atrium with oxygen-rich blood and improve coronary oxygen supply, which might be better for heart recovery.

Different types of antibiotics were used throughout the course of the disease. The structural abnormality of the heart and congestive heart failure increased pulmonary edema and aggravated pulmonary infection. Meanwhile, longer duration of ECMO increased the risk of bloodstream infection. Although the outcome in our research was favorable, it is important to note that the case took a longer ECMO course to achieve lung recovery[16]. Most previous studies had demonstrated the use of ECMO in patients with the Fontan operation for cardiac support, but this case illustrated its value as a bridge to lung recovery in acute respiratory failure due to pH1N1 infection.

The circulation after the modified Fontan operation is different from that of patients who does not undergo the operation. There are certainly many differences between them when they receive the treatment of ECMO. Due to the special cardiac structure and circulatory characteristics, it might be better for them to choose an active circulation support earlier.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Critical care medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Apiratwarakul K, Thailand; Cabezuelo AS, Spain; Sharma D, India S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Peer SM, Deatrick KB, Johnson TJ, Haft JW, Pagani FD, Ohye RG, Bove EL, Rojas-Peña A, Si MS. Mechanical Circulatory Support for the Failing Fontan: Conversion to Assisted Single Ventricle Circulation-Preliminary Observations. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2018;9:31-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Töpfer L, Menk M, Weber-Carstens S, Spies C, Wernecke KD, Uhrig A, Lojewski C, Jörres A, Deja M. Influenza A (H1N1) vs non-H1N1 ARDS: analysis of clinical course. J Crit Care. 2014;29:340-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kumar A, Zarychanski R, Pinto R, Cook DJ, Marshall J, Lacroix J, Stelfox T, Bagshaw S, Choong K, Lamontagne F, Turgeon AF, Lapinsky S, Ahern SP, Smith O, Siddiqui F, Jouvet P, Khwaja K, McIntyre L, Menon K, Hutchison J, Hornstein D, Joffe A, Lauzier F, Singh J, Karachi T, Wiebe K, Olafson K, Ramsey C, Sharma S, Dodek P, Meade M, Hall R, Fowler RA; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group H1N1 Collaborative. Critically ill patients with 2009 influenza A(H1N1) infection in Canada. JAMA. 2009;302:1872-1879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 942] [Cited by in RCA: 980] [Article Influence: 61.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rood KL, Teele SA, Barrett CS, Salvin JW, Rycus PT, Fynn-Thompson F, Laussen PC, Thiagarajan RR. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support after the Fontan operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142:504-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Walters HL 3rd, Mavroudis C, Tchervenkov CI, Jacobs JP, Lacour-Gayet F, Jacobs ML. Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project: double outlet right ventricle. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:S249-S263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jaber S, Conseil M, Coisel Y, Jung B, Chanques G. [ARDS and influenza A (H1N1): patients' characteristics and management in intensive care unit. A literature review]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2010;29:117-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Brodie D. The Evolution of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Adult Respiratory Failure. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15:S57-S60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cooper DS, Jacobs JP, Moore L, Stock A, Gaynor JW, Chancy T, Parpard M, Griffin DA, Owens T, Checchia PA, Thiagarajan RR, Spray TL, Ravishankar C. Cardiac extracorporeal life support: state of the art in 2007. Cardiol Young. 2007;17 Suppl 2:104-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Anderson PA, Sleeper LA, Mahony L, Colan SD, Atz AM, Breitbart RE, Gersony WM, Gallagher D, Geva T, Margossian R, McCrindle BW, Paridon S, Schwartz M, Stylianou M, Williams RV, Clark BJ 3rd; Pediatric Heart Network Investigators. Contemporary outcomes after the Fontan procedure: a Pediatric Heart Network multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:85-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bock MJ, Pahl E, Rusconi PG, Boyle GJ, Parent JJ, Twist CJ, Kirklin JK, Pruitt E, Bernstein D. Cancer recurrence and mortality after pediatric heart transplantation for anthracycline cardiomyopathy: A report from the Pediatric Heart Transplant Study (PHTS) group. Pediatr Transplant. 2017;21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Deal BJ, Costello JM, Webster G, Tsao S, Backer CL, Mavroudis C. Intermediate-Term Outcome of 140 Consecutive Fontan Conversions With Arrhythmia Operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101:717-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Woods RK, Ghanayem NS, Mitchell ME, Kindel S, Niebler RA. Mechanical Circulatory Support of the Fontan Patient. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2017;20:20-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | d'Udekem Y, Iyengar AJ, Galati JC, Forsdick V, Weintraub RG, Wheaton GR, Bullock A, Justo RN, Grigg LE, Sholler GF, Hope S, Radford DJ, Gentles TL, Celermajer DS, Winlaw DS. Redefining expectations of long-term survival after the Fontan procedure: twenty-five years of follow-up from the entire population of Australia and New Zealand. Circulation. 2014;130:S32-S38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 339] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Oldenburger NJ, Mank A, Etnel J, Takkenberg JJ, Helbing WA. Drug therapy in the prevention of failure of the Fontan circulation: a systematic review. Cardiol Young. 2016;26:842-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vogel DJ, Murray J, Czapran AZ, Camporota L, Ioannou N, Meadows CIS, Sherren PB, Daly K, Gooby N, Barrett N. Veno-arterio-venous ECMO for septic cardiomyopathy: a single-centre experience. Perfusion. 2018;33:57-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gandhi NN, Hartman ME, Williford WL, Peters MA, Cheifetz IM, Turner DA. Successful use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for pH1N1-induced refractory hypoxemia in a child with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12:e398-e401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |