Published online Sep 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i25.8945

Peer-review started: January 25, 2022

First decision: May 9, 2022

Revised: May 21, 2022

Accepted: July 21, 2022

Article in press: July 21, 2022

Published online: September 6, 2022

Processing time: 213 Days and 0.2 Hours

Portal venous gas (PVG) is a rare clinical condition usually indicative of severe disorders, including necrotizing enterocolitis, bowel ischemia, or bowel wall rupture/infarction. Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) is a rare illness characterized by an infiltration of gas into the intestinal wall. Emphysematous cystitis (EC) is relatively rare and characterized by intramural and/or intraluminal bladder gas best depicted by cross-sectional imaging. Our study reports a rare case coexistence of PVG presenting with PI and EC.

An 86-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency room due to the progressive aggravation of pain because of abdominal fullness and distention, complicated with vomiting and stopping defecation for 4 d. The abdominal computed tomography (CT) plain scan indicated intestinal obstruction with ischemia changes, gas in the portal vein, left renal artery, superior mesenteric artery, superior mesenteric vein, some branch vessels, and bladder pneumatosis with air-fluid levels. Emergency surgery was conducted on the patient. Ischemic necrosis was found in the small intestine approximately 110 cm below the Treitz ligament and in the ileocecal junction and ascending colon canals. This included excision of the necrotic small intestine and right colon, fistulation of the proximal small intestine, and distal closure of the transverse colon. Subsequently, the patient displayed postoperative short bowel syndrome but had a good recovery. She received intravenous fluid infusion and enteral nutrition maintenance every other day after discharge from the community hospital.

Emergency surgery should be performed when CT shows signs of PVG with PI and EC along with a clinical situation strongly suggestive of bowel ischemia.

Core Tip: Portal venous gas (PVG) caused by intestinal necrosis is a severe condition requiring surgery. PVG with superior mesenteric vessel gas, pneumatosis intestinalis (PI), and emphysematous cystitis (EC) reflect different stages of the same pathophysiological disorder. The specificity of PVG, PI, and mesenteric vein gas to computed tomography diagnosis of acute intestinal ischemia is nearly 100%. The coexistence of PVG, PI, and mesenteric venous gas can be an important diagnostic marker for acute ischemic bowel disease. When intestinal ischemia or necrosis is suspected, active surgical exploration should be the first line of treatment. It is rare for PVG to be complicated with superior mesenteric vessels gas, PI, and EC.

- Citation: Hu SF, Liu HB, Hao YY. Portal vein gas combined with pneumatosis intestinalis and emphysematous cystitis: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(25): 8945-8953

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i25/8945.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i25.8945

Portal venous gas (PVG) is a rare gas accumulation in the portal vein system (from the superior mesenteric vein and its branches to the liver). Clinically, PVG is considered to be one of the non-specific signs in major abdominal diseases rather than a specific disease entity. There is an increasing number cases of PVG with wide application of computed tomography (CT). However, it is unusual for PVG to be complicated with superior mesenteric vessel gas, pneumatosis intestinalis (PI), and emphysematous cystitis (EC). Here, we describe the diagnosis and treatment of this case.

Due to abdominal pain and distension, an elderly woman went to the emergency room of a hospital.

Due to abdominal fullness and distention, she suffered from the progressive aggravation of pain, complicated with vomiting and stopping defecation for 4 d.

Medical history includes coronary heart disease, atrial flutter, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and chronic renal insufficiency.

The body temperature was recorded as 36.7 °C, heart rate 108/min, respiratory rate 22/min, and blood pressure 110/68 mmHg. The clinical examination showed symptoms such as indifference, a slow response, painful appearance, abdominal fullness and distension, scattered tenderness and mild rebound tenderness, no obvious muscle tension, with drum sound and borborygmus disappearing when performing percussion.

The laboratory examination showed normal white blood cells, with hemoglobin 80 g/L, red blood cell (RBC) count 2.95 × 109/L, platelet count 123 × 109/L, neutrophil proportion 82.8%, C-reactive protein (CRP) > 320 mg/L, prothrombin time 17 s, activated partial thromboplastin time 48.6 s, fibrinogen 7.44 g/L, D-dimer 5920 µg/mL, procalcitonin 19.75 ng/mL, albumin 28.6 g/L, serum creatinine 186.3 µmol/L, brain natriuretic peptide 347.26 pg/mL, CK-MB 698.1 ng/mL, and cardiac troponin I 0.1 ng/mL and her electrocardiogram showed atrial flutter.

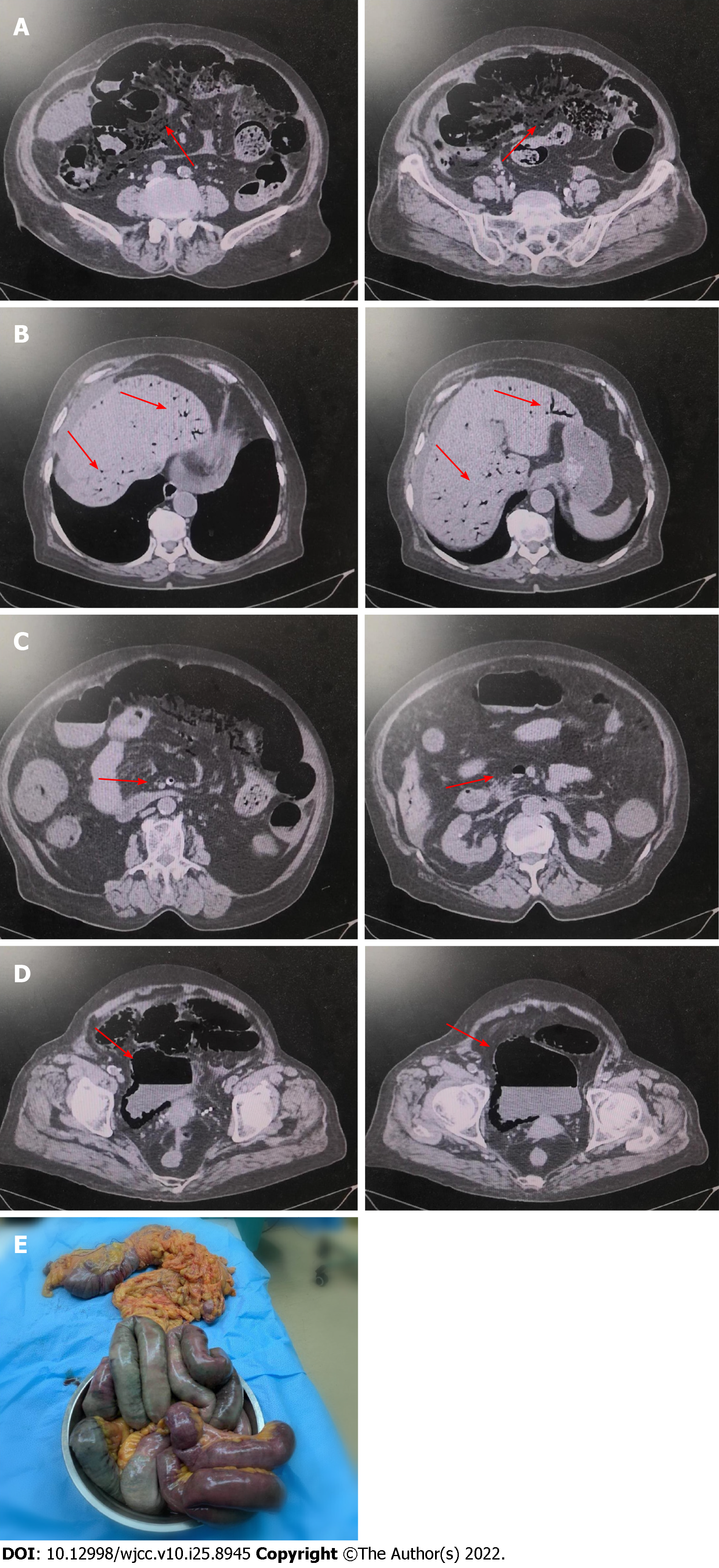

According to abdominal ultrasound examination, intrahepatic blood vessels were extensively pneumatized, and the gallbladder wall was not smooth and had calculi. Cardiac ultrasound examination showed an enlarged left atrium and thickened aortic ventricle with pericardial effusion (7 mm). As per the chest CT examination, pericardial effusion and lung texture were increased, with a little shadow in the lower lobe of the left lung, which may be caused by inflammation. Abdominal CT plain scan showed abdominal free-air, ascites, dilated small intestine lumen with gas, and effusion scattered signs at the air-fluid level. There were multiple gas density shadows between the intestinal walls, which was consistent with intestinal obstruction and intestinal ischemia changes (Figure 1A). Multiple dendritic gas density shadows were visible in the liver and liquid density shadows around the liver (Figure 1B). Gas occurs in the portal vein, left renal artery, superior mesenteric artery, superior mesenteric vein, and some branch vessels (Figure 1C). Figure 1D shows bladder pneumatosis complicated with air-fluid levels. Figure 1E shows histopathological examination of surgical specimens confirmed the changes caused by mesenteric ischemia.

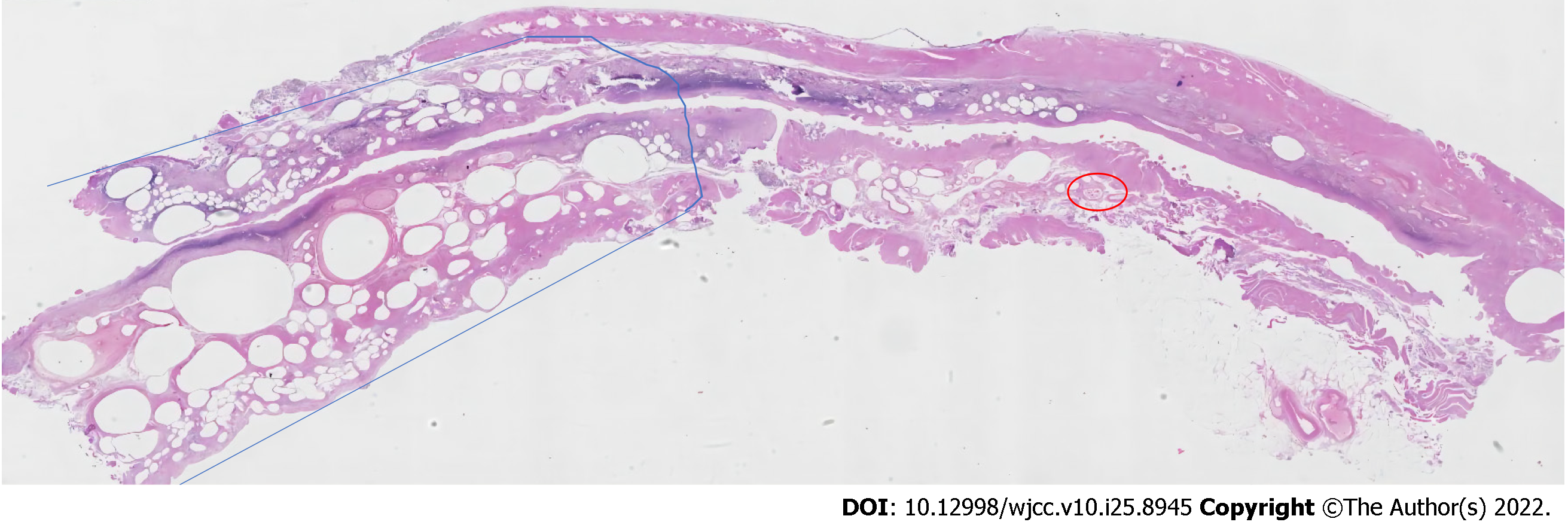

Upon microscopic examination, the patient did have coagulation necrosis of some small intestinal colon mucosa, erosion with ulceration, muscle degeneration like a honeycomb, hematoma formation in the submucosa, and thrombosis in the blood vessels, all of which may be caused by ischemic bowel disease. Congestion occurred in the vessel inside the omentum, with thrombosis in hemorrhage (Figure 2).

The final diagnosis was intestinal obstruction, intestinal necrosis, portal vein gas, superior mesenteric vessel gas, pneumatosis intestinalis, emphysematous cystitis, and acute mesenteric ischemia.

During an emergency laparotomy, 500 mL purulent ascites was found in the abdominal cavity. The section from the small intestine about 110 cm below the Treitz ligament to the remaining whole small intestine and ileocecal junction, as well as the intestinal canal of ascending colon, was dilated. The intestinal wall was gray and stiff, displaying "spot"-like ischemic necrosis, obvious edema, and no peristalsis. Snow-holding sensation and thrombosis within mesenteric vessels can be felt when the diseased intestinal canal is squeezed. Therefore, these surgical procedures were performed, including necrotic small intestine and right colon excision, proximal small intestine fistulation, and distal transverse colon closure.

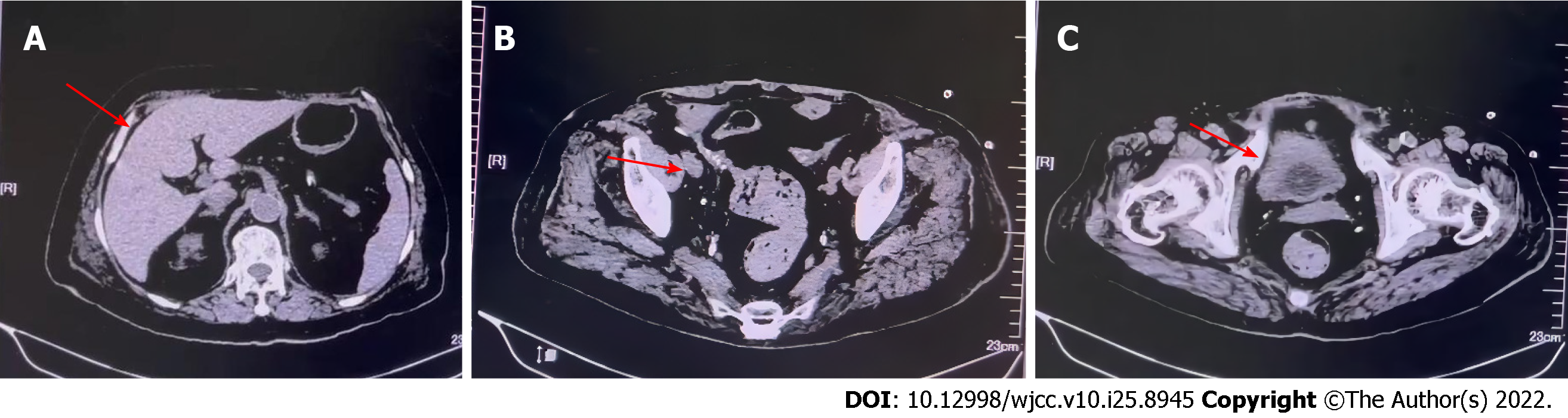

Following anti-infection, supportive transfusions of RBCs and platelets, crystalloid rehydration, and nutritional support were administered; the patient’s postoperative recovery was uneventful. In a step-like manner, infection indicators decreased to nearly normal levels. There were no noteworthy abnormalities in abdominal signs. On the eighth postoperative day, an abdominal CT plain scan presented gas in the portal vein, left renal artery, superior mesenteric artery, superior mesenteric vein, intestinal wall, and bladder was entirely absorbed (Figure 3A-C). The diet has returned to normal. Urine was normal, the water-like stool was smoothly drained from the stoma, and the amount was slightly large. We performed the support treatment of enteral nutrition with intravenous water and electrolyte supplement of 1000 to 1500 mL/d in the presence of oliguria and aggravation of renal insufficiency caused by short bowel syndrome. The patient was discharged on the 37th postoperative day. Subsequently, she received intravenous fluid infusion and enteral nutrition maintenance every other day in the community hospital.

PVG is a relatively rare imaging manifestation in the clinic that refers to abnormal accumulation of gas in the portal vein and its branches for various reasons. The portal vein trunk is formed by the superior mesenteric vein and the splenic vein, which after entering the liver, divides into left and right branches of the portal vein. As per the report by Wolfe and Evens, gas can accumulate in the intrahepatic portal vein branches and/or extrahepatic portal vein trunk and mesenteric vein in abdominal X-rays of newborns with necrotizing enterocolitis[1]. With the advancement of imaging technology, people progressively realize that PVG is not a disease and cannot be used as a predictor of death alone; however, it may be severe and complicated iatrogenic or non-iatrogenic manifestations of abdominal infection, abdominal trauma, mesenteric ischemia, diverticulitis, gastrointestinal diseases, and gastric ulcer, or the difficulties of duodenal perforation, diving, accidental intake of hydrogen peroxide with high concentration, and endoscopic surgery[2-5].

Three main pathophysiological mechanisms cause PVG: (1) Gastrointestinal mucosal injury that makes gas in the gastrointestinal cavity enter the mesenteric portal vein system through the injured site or mucosa with increased permeability, such as intestinal ischemia, endoscopic examination, and operation; (2) the gastrointestinal lumen is dilated, the pressure in the intestinal lumen increases, and edema or even ischemic necrosis may occur in some intestinal canals, which makes the lumen gas enter the portal vein system, such as trauma or intestinal obstruction; and (3) bacterial theory indicates that on the one hand, gas-producing bacteria invade submucosa to produce gas, which is absorbed by the submucosal blood vessels, and on the other hand, bacteria directly invade blood to form septicemia or phlebitis to produce gas, etc[6].

PI is also a rare pathology, with a global incidence of 0.03%and a threefold increase in males[7-10]. It is also a common radiological sign, with over 60 different causes[11]. PI can be primary or secondary to other diseases, with the latter accounting for 85%of cases. These other diseases include abdominal trauma, intestinal obstruction, inflammatory bowel disease, malignant tumor, chemoradiotherapy, chronic lung diseases, and connective tissue diseases[12-14]. However, the mechanism by which gas enters the intestinal wall is unknown. To explain this mechanism, several hypotheses have been proposed, such as the pulmonary, mechanical, and bacterial hypotheses[15]. According to pulmonary theory, chronic lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma can rupture alveoli, causing mediastinal emphysema and trapping gas in the intestinal wall via the aorta and mesenteric vessels. The mechanical theory of cyst formation refers to increased intraluminal pressure caused by intestinal obstruction or other diseases that can cause mucosal damage and cyst formation. The bacterial theory refers to intestinal bacteria that produce gas and trap it in the submucosa[16], as opposed to aerogenic bacteria that directly penetrate the intestinal mucosa and produce gas[17]. PI is sometimes an incidental finding, but it can foreshadow a life-threatening intraabdominal condition in some clinical settings, particularly in the presence of peritonitis, metabolic acidosis, and portal venous gas[18]. The treatment chosen is determined by the complications and underlying causes of PI. For individuals with visible manifestations of PI, conservative treatments such as oxygen therapy, antibiotics, and parenteral nutrition are recommended[19]. We did not perform a colonoscopy because the patient had symptoms of peritonitis and apathy, and CT indicated that the diseased bowel was concentrated in the small intestine. However, surgical treatment is recommended if the patient has surgical complications such as intestinal obstruction, intestinal perforation, bleeding, intestinal ischemia, and necrosis, or the presence of gas in the portal vein[20-22].

It is particularly rare that PVG and mesenteric vein and intestinal pneumatosis occur, with the occurrence rates of 3%-14% and 6%-28%, respectively, which is a characteristic manifestation of acute intestinal ischemia[23]. In cases of intestinal ischemia, there are two processes for the production of PI. One is ischemic necrosis of the intestinal wall mucosa, and the other is mechanical damage of the intestinal wall mucosa that can cause gas in the intestinal lumen to enter the intestinal wall or (and) bacteria to invade the intestinal wall to create gas for repeated infection. PVG and PI reportedly represent different stages of the same pathophysiological condition[24]. PVG is generated using the same method as PI, and gas in the intestinal wall further enters the portal vein system without a venous valve through the intestinal wall venules and lymphatic vessels[25]. The gas shadow can spread all over the left and right branches and trunk of the portal vein and even invade the superior mesenteric vein in individuals with severe disease[26]. The incidence of PVG related to PI is generally caused by intestinal ischemia. PVG related to PI is a severe disease and is related to poor prognosis[27,28]. Among them, intestinal necrosis is the most common cause of mortality in adult PVG patients (43%-75%). PVG, complicated with intestinal ischemia or necrosis, indicates a poor prognosis. Furthermore, the severity of PVG is also associated with basic diseases, and life risks may occur in patients with serious diseases[29]. As a result, Matsuoka et al[30] noted that intestinal necrosis had occurred in many cases in diagnosis, and the infarcted intestinal segment needed to be removed. Recently, Koizumi et al[31] through statistical analysis of Japan's hospitalization database, found that 53% of PVG patients have potential intestinal ischemic diseases, while the hospitalization mortality rate is 27.3%, 32% of patients have received surgical treatment, and the mortality rate has significantly decreased, similar to the results of García-Moreno et al[32]. Hence, intestinal ischemia or necrosis is still an important cause of PVG.

EC is defined by the accumulation of air inside the bladder wall and/or lumen. It is one of the uncommon varieties of urinary tract infections due to gas-producing bacteria. With a mortality rate of 7.4%, EC is a rare but critical condition[33]. It is commonly seen in elderly, diabetic females with an infective organism[33] and in immunocompromised people[34-36]. Very little information regarding emphysematous cystitis has been reported. Pathogens associated with this condition include gas-forming bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterococci[37,38].

In this scenario, the patient is elderly, and there are many risk factors of mesenteric ischemia in the past medical history, such as coronary heart disease, atrial flutter, atherosclerosis, diabetes, and chronic kidney diseases. The onset process is marked by an acute attack, with severe symptoms and non-obvious indicators in the early stages, followed by increasing aggravation in the later stages. There was no positive indication in the initial examination, making it difficult to accurately confirm the diagnosis. However, as the disease progressed, the patient developed symptoms of peritonitis and apathy, a potentially fatal infectious presentation in the elderly. Her condition did not improve when a high flow of oxygen was administered early in her hospitalization. The examination results showed neutrophil proportion 82.8%, CRP > 320 mg/L, and PCT 19.75 ng/mL, which showed that there was a bacterial infection in the patient. D-dimer: 5920 µg/mL; which is more than ten times higher than the normal value, representing the risk of thrombosis; CT image indicated that abdominal free-air, ascites, PVG, superior mesenteric arteriovenous (SMA) gas, PI and EC coexist. These results are strongly suggestive of mesenteric ischemia. Previous research has shown that PVG, PI, and CT have a 100% sensitivity to detect acute intestinal ischemia[23]. However, intramural gas and portal venous gas are frequently discovered. Gas in the SMA is extremely rare, but it is critical for detecting severe mesenteric ischemia[39,40]. Only 2 cases were found in the literature; 1 patient had diffuse intestinal necrosis with SMA occlusion, and the other patient had acute aortic dissection with intestinal necrosis. Non-surgical patients with ascites (by CT), peritoneal irritation (by physical examination), and shock (by checking vital signs) are thought to be in life-threatening conditions[41]. It appears to be appropriate as a convenient laparotomy decision criteria. Based on the above results, it shall not preclude the combined action of the strangulated intestinal obstruction caused by mesenteric artery (for the abdominal small intestinal blood supply) embolism due to thrombus from coronary heart disease, atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation, atherosclerosis, and other cardiovascular diseases, the higher intestinal lumen pressure, intestinal mucosal layer edema or necrosis, and destroyed mucosal barrier, initiating intestinal lumen gas to penetrate into the intestinal wall venules and flow back to the portal vein through mesenteric vessels, in the meantime, intestinal and abdominal gas-producing bacterial infection disturbing intestinal mucosal venules, and the direct infection of intravenous gas-producing bacteria[42]. In patients, however, changes in superior mesenteric artery gas, left renal artery gas, and EC can be explained by gas infiltration into the intestinal lumen after intestinal canal ischemia and direct infection with aerogenic bacteria, which is yet to be definitively proven. This may be related to E. coli, which is the most common cause of EC[43].

Through well-timed emergency surgical exploration, it was established that the range of the necrotic intestinal canal was consistent with the changes in the ischemic region after superior mesenteric artery embolization. The corresponding intestinal segment and mesentery were removed during the operation to save the patient's life. According to previous literature[18], that PVG generally indicates intestinal wall ischemia and necrosis, which is often the late sign of intestinal wall ischemic necrosis, but PVG has no sign effect on the severity of intestinal wall ischemic necrosis. Liebman et al[44] and Kinoshita et al[45] reported that PVG is an evident indication of surgical exploration in the acute abdomen. PVG, however, is not an absolute indication for emergency surgery, as more studies have revealed its presence in the development of various diseases[2-5].

Although surgical removal of the damaged portion was previously thought to be the only effective therapy, advanced imaging modalities such as CT have shown that some patients can recover with non-surgical, conservative treatments[44,46-49]. PVG was mostly not associated with intestinal necrosis in the patients who recovered, implying that not all PVG patients require surgery[49]. However, the patient had peritonitis and apathy, and PI, PVG, and mesenteric venous gas strongly indicate acute ischemic bowel disease. Cases of PI and PVG with benign etiology have been reported infrequently in the literature[28]. The presence of both almost always indicates mesenteric infarction and bowel necrosis[50]. This has a poor prognosis, with mortality rates ranging from 39% to 80%[24,50], and in some series approaching 100%[50]. Imaging alone makes it difficult to distinguish between benign and life-threatening causes[24]. Instead, the patient's clinical picture and laboratory findings should guide this decision. Thus, we believe that caring clinicians should base their decision to operate on the patient's clinical state, particularly any signs of peritonitis and other laboratory adjuncts. Most studies agree that exploratory laparotomy or laparoscopy is justified when in doubt and in patients who can tolerate surgery[24,50]. Diagnostic laparoscopy, which is less invasive, should be considered first if the clinical situation allows it. However, a complete abdominal laparotomy is still recommended if the patient is diagnosed with mesenteric infarction and intestinal necrosis via laparoscopy. Especially, active surgical exploration is the first-line treatment for intestinal necrosis when ischemia or necrosis is suspected[48]. The treatment given to this patient is consistent with Piton et al’s report[51]. To avoid the deterioration of disease for intestinal necrosis, these ischemic intestinal canals should be actively removed during the operation. However, in the absence of ischemia of the intestinal wall, conservative treatments, and close observation must be followed.

The clinical treatment of PVG must be provided as per the etiology. Gorospe[48] outlined the "ABC" grading treatment principle for clinical treatment of PVG: (1) If the onset of the disease is urgent and the clinical symptoms are severe, and CT displays signs of intestinal ischemia, and intestinal necrosis, the mortality rate of such patients can reach 75%, which should be dynamically treated, and emergency laparotomy should be carried out; (2) If the onset of the disease is relatively slow and the clinical symptoms are comparatively mild, the mortality rate of such patients is between 20% and 30%, which could be closely observed initially, and provided with surgical treatment if necessary; and (3) If there is only PVG without emergency or only PVG after the operation, conservative treatment such as fasting and gastrointestinal decompression can be provided.

We studied the diagnosis and treatment of this patient with PVG, secondary to changes of mesenteric ischemia, complicated with superior mesenteric vessels gas, PI, and EC. Therefore, once the PVG, complicated with PI and mesenteric vein gas, is found in CT examination, we must thoroughly investigate the causes of various factors and give priority to mesenteric ischemia and related diseases. Once emergency treatment is needed, we should actively find the etiology and carefully determine a treatment scheme.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nakaji K, Japan; Piltcher-da-Silva R, Brazil; Trna J, Czech Republic A-Editor: Antwi SO, United States S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Gong ZM

| 1. | Wolfe JN, Evans WA. Gas in the portal veins of the liver in infants; a roentgenographic demonstration with postmortem anatomical correlation. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1955;74:486-488. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Siaffa R, Luciani M, Grandjean B, Coulange M. Massive portal venous gas embolism after scuba diving. Diving Hyperb Med. 2019;49:61-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Youssef EW, Chukwueke VS, Elsamaloty L, Moawad S, Elsamaloty H. Accidental Concentrated Hydrogen Peroxide Ingestion Associated with Portal Venous Gas. J Radiol Case Rep. 2018;12:12-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mohammed AH, Mohammed AH, Khot UP, Thomas D. Portal venous gas--case report and review of the literature. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:400-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lupescu I, Masala N, Capsa R, Câmpeanu N, Georgescu SA. CT and MRI of acquired portal venous system anomalies. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:393-398. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Huang LH, Zhao YP, Liu Q. Research progress of hepatic portal vein pneumatosis. Jiangxi Yiyao. 2019;54:292-294. |

| 7. | Moyon FX, Molina GA, Tufiño JF, Basantes VM, Espin DS, Moyon MA, Cevallos JM, Palacios NE, Parra RA, Eras KR. Pneumoperitoneum and Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis, a dangerous mixture. A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;74:222-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rathi C, Pipaliya N, Poddar P, Pandey V, Ingle M, Sawant P. A Rare Case of Hypermobile Mesentery With Segmental Small Bowel Pneumatosis Cystoides Intestinalis. Intest Res. 2015;13:346-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rachapalli V, Chaluvashetty SB. Pneumatosis Cystoides Intestinalis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:TJ01-TJ02. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Koysombat K, Capanna MV, Stafford N, Orchard T. Combination therapy for systemic sclerosis-associated pneumatosis intestinalis. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Torres US, Fortes CD, Salvadori PS, Tiferes DA, Giuseppe D. Pneumatosis from esophagus to rectum: a comprehensive review focusing on clinico-radiological differentiation between benign and life-threatening causes. Seminars in ultrasound, CT and MRI; 2018: Elsevier. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Wu LL, Yang YS, Dou Y, Liu QS. A systematic analysis of pneumatosis cystoids intestinalis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4973-4978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ling F, Guo D, Zhu L. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis: a case report and literature review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Goodman RA, Riley TR 3rd. Lactulose-induced pneumatosis intestinalis and pneumoperitoneum. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:2549-2553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bamakhrama K, Abdulhady L, Vilmann P. Endoscopic ultrasound diagnosis of pneumatosis cystoides coli initially misdiagnosed as colonic polyps. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E195-E196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Brighi M, Vaccari S, Lauro A, D'Andrea V, Pagano N, Marino IR, Cervellera M, Tonini V. "Cystamatic" Review: Is Surgery Mandatory for Pneumatosis Cystoides Intestinalis? Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:2769-2775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gillon J, Tadesse K, Logan RF, Holt S, Sircus W. Breath hydrogen in pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. Gut. 1979;20:1008-1011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kernagis LY, Levine MS, Jacobs JE. Pneumatosis intestinalis in patients with ischemia: correlation of CT findings with viability of the bowel. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:733-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Arikanoglu Z, Aygen E, Camci C, Akbulut S, Basbug M, Dogru O, Cetinkaya Z, Kirkil C. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis: a single center experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:453-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pata F, Di Saverio S. Pneumatosis Cystoides Intestinalis with Pneumoperitoneum. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:e17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kancherla D, Vattikuti S, Vipperla K. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis: Is surgery always indicated? Cleve Clin J Med. 2015;82:151-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Di Pietropaolo M, Trinci M, Giangregorio C, Galluzzo M, Miele V. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis: case report and review of literature. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2020;13:31-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Huo FT, Leng TG, Bai RJ, Qi J. CT diagnosis of acute intestinal ischemia. Int J Med Radiol. 2004;27:373-376, 379. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wayne E, Ough M, Wu A, Liao J, Andresen KJ, Kuehn D, Wilkinson N. Management algorithm for pneumatosis intestinalis and portal venous gas: treatment and outcome of 88 consecutive cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:437-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wiesner W, Khurana B, Ji H, Ros PR. CT of acute bowel ischemia. Radiology. 2003;226:635-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mourad FH, Leong RW. Gas In The Hepatic Portal Venous System Associated With Ischemic Colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Peter SDS, Abbas MA, Kelly KA. The spectrum of pneumatosis intestinalis. Arch Surg. 2003;138:68-75. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Ho LM, Paulson EK, Thompson WM. Pneumatosis intestinalis in the adult: benign to life-threatening causes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1604-1613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Niu DG, Li C, Fang HC. Hepatic portal venous gas associated with transcathete cardiac defibrillator implantation: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;44:57-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Matsuoka T, Kobayashi K, Lefor AK, Sasaki J, Shinozaki H. Mesenteric ischemia with pneumatosis intestinalis and portal vein gas associated with enteral nutrition: a series of three patients. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1160-1164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Koizumi C, Michihata N, Matsui H, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. In-Hospital Mortality for Hepatic Portal Venous Gas: Analysis of 1590 Patients Using a Japanese National Inpatient Database. World J Surg. 2018;42:816-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | García-Moreno F, Carda-Abella P. Hepatic portal venous gas. Ann Hepatol. 2007;6:185. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Schicho A, Stroszczynski C, Wiggermann P. Emphysematous Cystitis: Mortality, Risk Factors, and Pathogens of a Rare Disease. Clin Pract. 2017;7:930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Charkhand B, Valeshabad AK, Farahany J, Warncke J, Hayrapetian A, Nehler MR, Wilson S. An atypical case of emphysematous cystitis in a young non-diabetic patient. World J Nephrol Urol. 2019;8:17-18. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Baldolli A, Nicolle A, Belin A, Pineau S, Milliez PU, Verdon R. Emphysematous cystitis in a patient with a left ventricular assist device. Surg Infect Case Rep. 2016;1:11-12. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 36. | Hudnall MT, Jordan BJ, Horowitz J, Kielb S. A case of emphysematous cystitis and bladder rupture. Urol Case Rep. 2019;24:100860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Eken A, Alma E. Emphysematous cystitis: The role of CT imaging and appropriate treatment. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:E754-E756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | De Baets K, Baert J, Coene L, Claessens M, Hente R, Tailly G. Emphysematous cystitis: report of an atypical case. Case Rep Urol. 2011;2011:280426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Fujiwara S, Sekine Y. Gas in the superior mesenteric artery. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Numata S, Tsutsumi Y, Ohashi H. Gas in the superior mesenteric artery: severe malperfusion and bowel necrosis caused by acute aortic dissection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43:1267-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Gonda M, Osuga T, Ikura Y, Hasegawa K, Kawasaki K, Nakashima T. Optimal treatment strategies for hepatic portal venous gas: A retrospective assessment. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:1628-1637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Cui L, Wang J, Wang S, Huang M, Li H, Zhang W. Hepatic portal venous gas: sonographic appearance and clinical significance. Zhongguo Yixue Yingxiang Jishu. 2005;21:1242-1244. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Thomas AA, Lane BR, Thomas AZ, Remer EM, Campbell SC, Shoskes DA. Emphysematous cystitis: a review of 135 cases. BJU Int. 2007;100:17-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Liebman PR, Patten MT, Manny J, Benfield JR, Hechtman HB. Hepatic--portal venous gas in adults: etiology, pathophysiology and clinical significance. Ann Surg. 1978;187:281-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kinoshita H, Shinozaki M, Tanimura H, Umemoto Y, Sakaguchi S, Takifuji K, Kawasaki S, Hayashi H, Yamaue H. Clinical features and management of hepatic portal venous gas: four case reports and cumulative review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1410-1414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Chan SC, Wan YL, Cheung YC, Ng SH, Wong AM, Ng KK. Computed tomography findings in fatal cases of enormous hepatic portal venous gas. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2953-2955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Nelson AL, Millington TM, Sahani D, Chung RT, Bauer C, Hertl M, Warshaw AL, Conrad C. Hepatic portal venous gas: the ABCs of management. Arch Surg. 2009;144:575-81; discussion 581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Gorospe EC. Benign hepatic portal venous gas in a critically ill patient. ScientificWorldJournal. 2008;8:951-952. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 49. | Abboud B, El Hachem J, Yazbeck T, Doumit C. Hepatic portal venous gas: physiopathology, etiology, prognosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3585-3590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 50. | Schatz TP, Nassif MO, Farma JM. Extensive portal venous gas: Unlikely etiology and outcome. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;8C:134-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Piton G, Capellier G, Delabrousse E. Echography of the Portal Vein in a Patient With Shock. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:e443-e445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |