Published online Aug 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i22.7698

Peer-review started: February 16, 2022

First decision: April 16, 2022

Revised: April 19, 2022

Accepted: June 26, 2022

Article in press: June 26, 2022

Published online: August 6, 2022

Processing time: 155 Days and 15 Hours

Anal stenosis is a rare but frustrating condition that usually occurs as a complication of hemorrhoidectomy. The severity of anal stenosis can be classified into three categories: mild, moderate, and severe. There are two main surgical treatments for this condition: scar revision surgery and anoplasty; however, no studies have compared these two approaches, and it remains unclear which is preferrable for stenoses of different severities.

To compare the outcomes of scar revision surgery and double diamond-shaped flap anoplasty.

Patients with mild, moderate, or severe anal stenosis following hemorrhoidectomy procedures who were treated with either scar revision surgery or double diamond-shaped flap anoplasty at our institution between January 2010 and December 2015 were investigated and compared. The severity of stenosis was determined via anal examination performed digitally or using a Hill-Ferguson retractor. The explored patient characteristics included age, sex, preoperative severity of anal stenosis, preoperative symptoms, and preoperative adjuvant therapy; moreover, their postoperative quality of life was measured using a 10-point scale. Patients underwent proctologic follow-up examinations one, two, and four weeks after surgery.

We analyzed 60 consecutive patients, including 36 men (60%) and 24 women (40%). The mean operative time for scar revision surgery was significantly shorter than that for double diamond-shaped flap anoplasty (10.14 ± 2.31 [range: 7-15] min vs 21.62 ± 4.68 [range: 15-31] min; P < 0.001). The average of length of hospital stay was also significantly shorter after scar revision surgery than after anoplasty (2.1 ± 0.3 vs 2.9 ± 0.4 d; P < 0.001). Postoperative satisfaction was categorized into four groups: 45 patients (75%) reported excellent satisfaction (scores of 8-10), 13 (21.7%) reported good satisfaction (scores of 6-7), two (3.3%) had no change in satisfaction (scores of 3-5), and none (0%) had scores indicating poor satisfaction (1-2). As such, most patients were satisfied with their quality of life after surgery other than the two who noticed no difference due owing to the fact that they experienced recurrences.

Scar revision surgery may be preferable for mild anal stenosis upon conservative treatment failure. Anoplasty is unavoidable for moderate or severe stenosis, where cicatrized tissue is extensive.

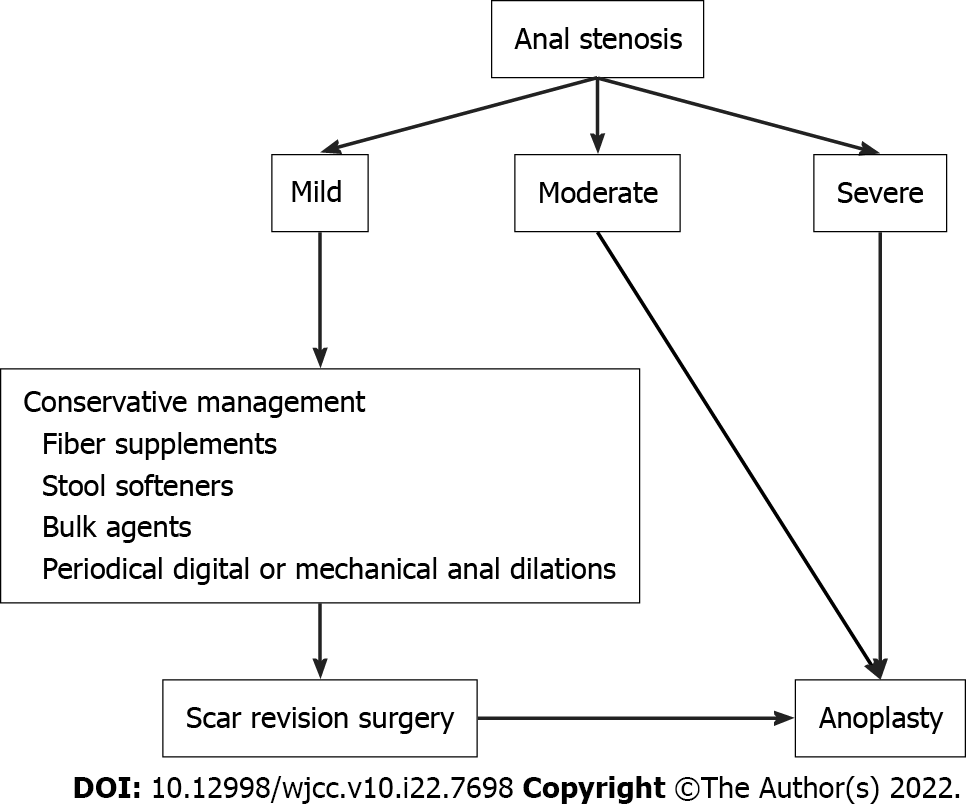

Core Tip: The severity of anal stenosis can be classified into three categories: mild, moderate, and severe. According to our study, we drew an algorithm for the management of anal stenosis based on severity. For mild anal stenosis, scar revision surgery can be attempted first if nonsurgical methods fail, with anoplasty performed if recurrence occurs. For moderate and severe anal stenosis, opting for anoplasty from the outset is the best option to prevent subsequent surgeries.

- Citation: Weng YT, Chu KJ, Lin KH, Chang CK, Kang JC, Chen CY, Hu JM, Pu TW. Is anoplasty superior to scar revision surgery for post-hemorrhoidectomy anal stenosis? Six years of experience. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(22): 7698-7707

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i22/7698.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i22.7698

Anal stenosis is defined as the narrowing of the anal canal due to contraction of the epithelial lining[1,2]. The normal anoderm is replaced with an inelastic fibrotic tissue, which renders the anal canal abnormally tight and non-pliable[3]. It is a rare but frustrating circumstance that commonly occurs as a complication of hemorrhoidectomy or other anorectal surgical procedure[4-6]. Anal stenosis may also develop due to inflammatory bowel disease, trauma, chronic laxative abuse, venereal disease, and local radiation therapy[7-10]. It is estimated that approximately 90% of anal stenoses are sequalae of hemorrhoidectomies[11-13]. Patients may have symptoms such as decreasing stool caliber, difficult defecation, bleeding, fecal incontinence, incomplete evacuation, anal pain, and/or diarrhea[4,11,14,15]. The severity of anal stenosis is classified into three degrees: mild, moderate, and severe; These are determined based on an anal examination with a Hill-Ferguson retractor or index-small finger[11,16]. For mild stenosis, conservative management methods such as fiber supplements, stool softeners, or bulk-forming agents are usually suggested; Periodical digital or mechanical anal dilations, as well as sphincterotomy, may also be performed[12,17]. For moderate-to-severe stenosis, a surgical approach is indicated[18,19], with the two main surgical methods being scar revision surgery and anoplasty. The former method involves excision of the scar tissue and suturing the wound, whereas the latter uses local flaps to excise the cicatrized tissue, dissect the stricture, and increase the anal canal size to lessen the severity of symptoms and recover normal anal function[20,21]. Ideally, the selected procedure should be simple to perform and be well-tolerated, with a low complication rate and good long-term results without recurrence. However, there are no studies comparing the two aforementioned surgical approaches, and it remains unclear whether the choice of procedure depends on the severity of the stenosis. Therefore, we performed this retrospective study to compare patients who underwent scar revision surgery to those who underwent anoplasty over a six-year period.

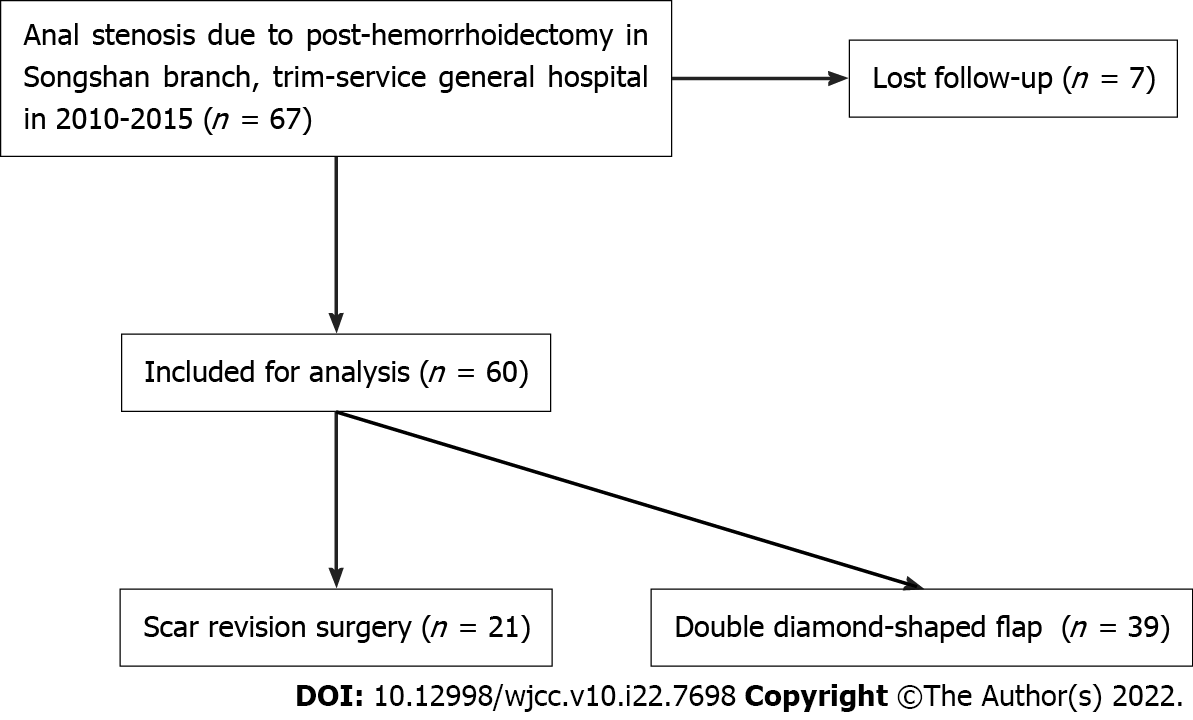

This retrospective cohort analysis included patients who were treated between January 2010 and December 2015 for mild-to-severe anal stenosis and who underwent scar revision surgery or double diamond-shaped flap at the Department of Surgery, Taiwan Adventist Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan (Figure 1). We included patients who were diagnosed with anal stenosis post-hemorrhoidectomy. Patients with this condition owing to other causes such as inflammatory bowel disease, tuberculosis, trauma, previous radiation therapy, and previous anal malignancy were excluded from the study, as were those who were lost to follow-up. Ultimately, 60 patients who fulfilled the selection criteria were included in the analysis.

Preoperative evaluation included clinical and proctologic examinations. The following variables were collected during the clinical examination: age; sex; the preoperative severity of anal stenosis, symptoms, and adjuvant therapy. A proctologic examination was performed digitally or using a Hill-Ferguson retractor to determine the severity of the stenosis. All the patients had first attempted conservative management methods but were unsuccessful, thereby necessitating surgical intervention to ameliorate their discomfort. All data were inputted into an electronic database.

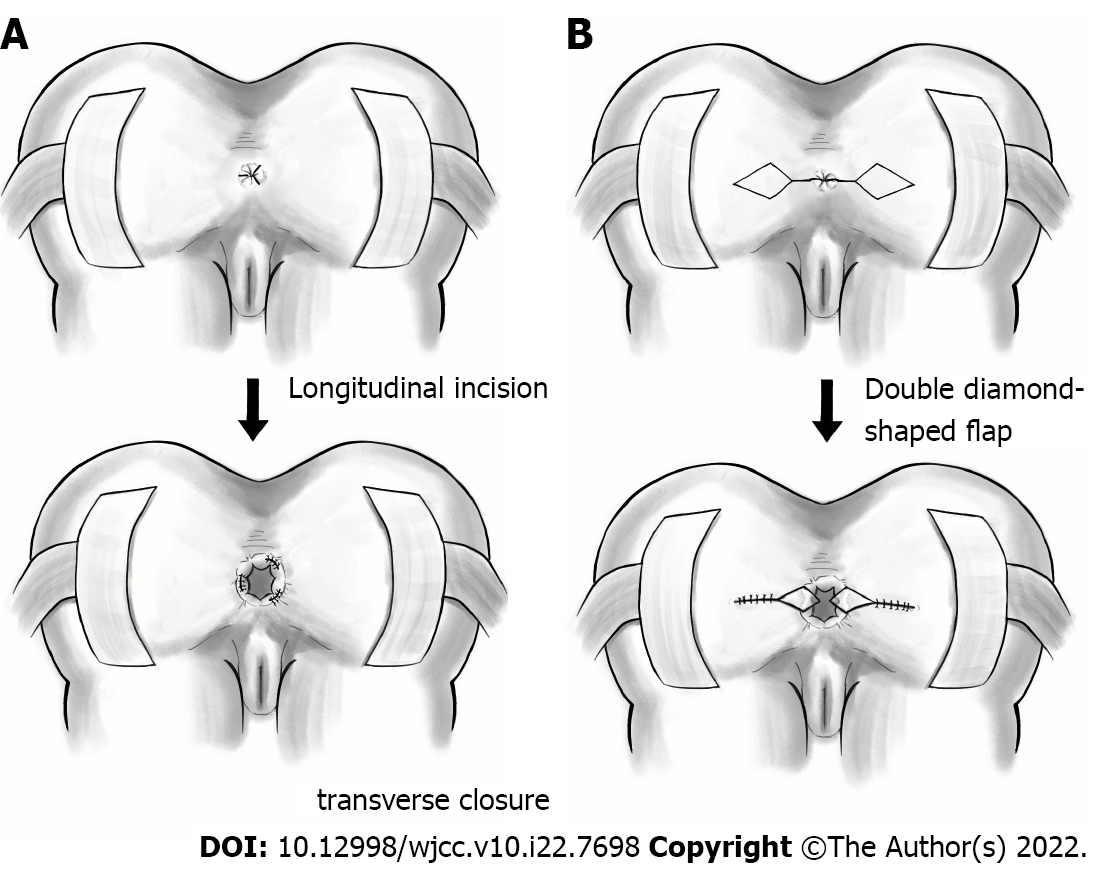

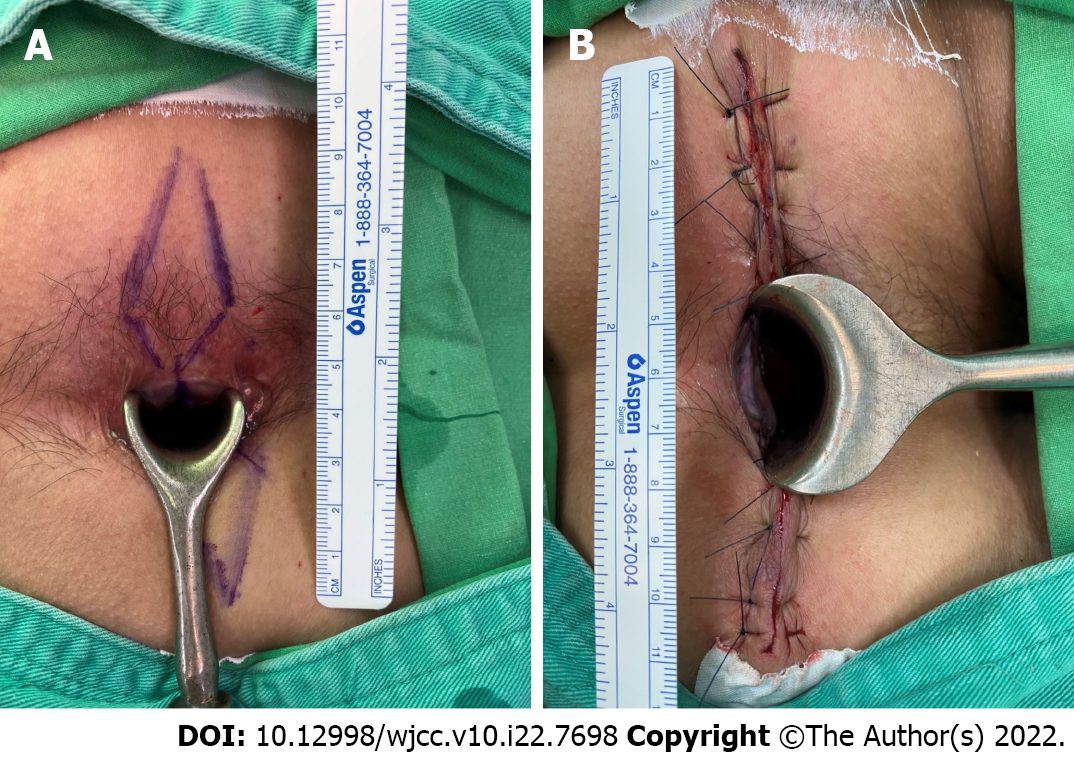

Full bowel preparation was performed preoperatively, and the same team performed all surgical procedures for all the patients. Scar revision surgery or double diamond-shaped flap was chosen according to the surgeon’s experiences and preference. We performed these two procedures under intravenous general anesthesia; moreover, a single dose of intravenous antibiotics (cefazolin) was administered upon the induction of anesthesia as a prophylactic against wound infection. The patients were placed in the jackknife position, and the skin was sterilized and draped per standard protocol. For scar revision surgery, the scar was commonly found in the 3, 7, and 11 o’clock directions. We removed the scar with a longitudinal incision through the stricture while controlling bleeding with wet epinephrine tape. The wound was closed with a 3-O catgut (transverse closure) and covered with gauze (Figure 2A). For the double diamond-shaped flap anoplasty, a diamond-shaped flap from the adjacent perianal skin was delineated and dissected together with its pedicle on both sides. The dissection was generally performed deep into the fascia to create a well-perfused, tension-free flap transposed into the anal canal. The flap was then introduced into the anal canal defect for wound coverage (Figures 2B and 3).

Before discharge, the operative time, length of hospital stay, and postoperative complications were recorded. The patients underwent scheduled clinical and proctologic examinations at the outpatient clinic 1, 2, and 4 wk after surgery. Subsequently, regular inspections were performed upon patient request. Patients were contacted by telephone after 6 mo and were invited to the outpatient clinic for a final follow-up evaluation. During their postoperative workups, the patients underwent clinical and proctologic evaluations during which the following variables were collected: postoperative symptoms, postoperative adjuvant therapy, recurrence, and postoperative quality of life. Recurrence was defined as experiencing symptoms of anal stenosis that could not relieved by conservative treatment. The patients’ postoperative quality of life was assessed using a satisfaction questionnaire that comprised a 10-point rating scale ranging from 1 (poor) to 10 (excellent). The satisfaction scores were grouped into four categories: excellent (8-10), good (6-7), same (3-5), and poor (1-2).

The patients’ characteristics are summarized as total numbers, percentages, and means ± standard deviations. Student’s t-test for paired samples was used to detect differences in the means of continuous variables over time. Statistical significance was set at a P-value < 0.05. The SPSS software for Windows, version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) was used to perform the statistical analyses.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of our hospital (approval No. 111-E-01). All procedures were performed under the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and those of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments, or comparable ethical standards. The requirement for informed consent was waived by the institutional review board of our hospital due to the retrospective nature of the study, and patient information was anonymized and de- identified prior to analysis.

The patients’ demographic data and characteristics are presented in Table 1. Thirty-six men (60%) and 24 women (40%) with anal stenosis underwent scar revision surgery or double diamond-shaped flap anoplasty between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2015. Among them, 8 with moderate or severe anal stenosis had previously undergone scar revision surgery, but underwent diamond-shaped flap anoplasty owing to recurrence; these individuals were categorized into the diamond-shaped flap anoplasty group. The median patient age was 54.65 ± 12.65 years (range: 27-76 years). All patients had previously undergone hemorrhoidectomy, and all reported having a poor quality of life due to anal stenosis. In terms of severity, 48.33%, 33.33%, and 18.33% of the patients had mild, moderate, and severe conditions, respectively. All patients had strained defecation; other symptoms are shown in Table 1. All patients had previously tried conservative management, and all were administered laxatives, while smaller proportions attempted other additional treatments. Ultimately, 21 patients (35%) underwent scar revision surgery while 39 (65%) underwent double diamond-shaped flap anoplasty.

| Scar revision surgery | Double diamond-shaped flap anoplasty | P value | Total | |

| Patient numbers | 21 (35%) | 39 (65%) | 60 | |

| Age (yr) | 54 ± 14.5 | 55 ± 11.8 | 0.773 | 54.65 ±12.65 |

| Sex (male/female) | 13/8 (61.9%/38.09%) | 23/16 (58.97%/41.03%) | 0.825 | 36/24 (60%/40%) |

| Preoperative severity of anal stenosis | < 0.001 | |||

| Mild | 17 (80.95%) | 12 (30.77%) | 29 (48.33%) | |

| Moderate | 4 (19.05%) | 16 (41.03%) | 20 (33.33%) | |

| Severe | 0 | 11 (28.21%) | 11 (18.33%) | |

| Preoperative symptoms | ||||

| Strained defecation | 21 (100%) | 39 (100%) | - | 60 (100%) |

| Incomplete evacuation | 13 (61.9%) | 26 (66.67%) | 0.712 | 39 (65%) |

| Painful evacuation | 4 (19.04%) | 25 (64.1%) | 0.001 | 29 (48.33%) |

| Defecation bleeding | 0 | 8 (20.51%) | 0.026 | 8 (13.33%) |

| Incontinence | 0 | 7 (17.95%) | 0.039 | 7 (11.67%) |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||||

| Laxative medication | 21 (100%) | 39 (100%) | - | 60 (100%) |

| Pain control medication | 4 (19.05%) | 25 (64.1%) | 0.001 | 29 (48.33%) |

| Digital dilatation | 7 (33.33%) | 17 (43.59%) | 0.439 | 24 (40%) |

The perioperative results are shown in Table 2. The mean operative times for scar revision surgery was significantly shorter for that for double diamond-shaped flap anoplasty (10.14 ± 2.31 [range: 7-15] min vs 21.62 ± 4.68 [range: 15-31] min; P < 0.001). The average of length of hospital stay was also significantly shorter in the former group (2.1 ± 0.3 d) than in the latter (2.9 ± 0.4 d; P < 0.001). Four patients in the double diamond-shaped flap group underwent urinary catheterization because of urinary retention, but the difference in this complication between the two groups was not significant (P = 0.129). None of the patients in our study experienced wound dehiscence, wound infection, postoperative fever, or postoperative bleeding.

| Patient numbers | 21 (35%) | 39 (65%) | 60 | |

| Operative time (min) | 10.14 ± 2.31 | 21.62 ± 4.68 | < 0.001 | 17.6 ± 6.8 |

| Length of hospital stay (d) | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 | 2.62 ± 0.52 |

| Complications | ||||

| Acute urinary retention | 0 | 4 (10.3%) | - | 4 (6.7%) |

| Wound dehiscence | 0 | 0 | 0.129 | 0 |

| Wound infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Postoperative fever | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Postoperative bleeding | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Finally, we investigated the postoperative conditions of the patients after 6 mo (Table 3). Two patients of moderate anal stenosis in the scar revision surgery group had strained defecation and one had incomplete evacuation; these were considered recurrence. None of the patients in the anoplasty group had any postoperative symptoms or required adjuvant therapy (i.e., there were no recurrences in this group). On their postoperative satisfaction questionnaires, 45 patients (75%) reported excellent satisfaction scores, whereas 13 (21.7%) and 2 (3.3%) reported good satisfaction and no change, respectively; the latter two were those who experienced recurrences. Importantly, there were a significant difference in satisfaction between the two groups (P = 0.035), with more satisfaction in double diamond-shaped flap anoplasty group.

| Scar revision surgery | Double-diamond-shaped flap anoplasty | P value | Total | |

| Patient numbers | 21 (35%) | 39 (65%) | 60 | |

| Postoperative symptoms | - | |||

| Strained defecation | 2 (9.52%) | 0 | 0.05 | 2 (3.33%) |

| Incomplete evacuation | 1 (4.76%) | 0 | 0.169 | 1 (1.67%) |

| Painful evacuation | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Defecation bleeding | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Incontinence | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||||

| Laxative medication | 2 (9.52%) | 0 | - | 2 |

| Pain control medication | 0 | 0 | 0.05 | 0 |

| Digital dilatation | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Recurrence | 2 (9.52%) | 0 | 0.05 | 2 (3.33%) |

| Quality of life | 0.035 | |||

| Poor (1–2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Same (3–5) | 2 (9.52%) | 0 | 2 (3.33%) | |

| Good (6–7) | 6 (28.57%) | 7 (17.95%) | 13 (21.67%) | |

| Excellent (8–10) | 13 (61.90%) | 32 (82.05%) | 45 (75%) |

Anal stenosis is not uncommon after anal surgery; its rate has been reported to range from 1.2% to 10% in patients who have undergone hemorrhoidectomy[22]. As mentioned in the Introduction, there are numerous causes of anoderm tissue scarring that can lead to anal stenosis or stricture. Mild anal stenosis is defined as a stenotic anal canal that can still be examined using a well-lubricated index finger or medium-size Hill-Ferguson retractor[11]. Most patients with mild anal stenosis can be managed nonsurgically using methods such as increasing fiber-rich food in the diet or using stool softening or bulk-forming agents[11,23]. Daily gentle self-digital or instrumental dilation with Hegar dilators can also be considered. Digital dilatation is a much simpler method and avoid the costs of Hegar dilators; however, patients may unintentionally injure the anal sphincter, resulting in further fibrosis and stricture and ultimately more serious stenosis[4,24]. Therefore, Hegar dilators used by surgeons while patients are under adequate anesthesia are a safer choice. Casadesus et al[3] described 4 patients who achieved satisfactory results with regular progressive self-dilatation using Hegar dilators. If conservative management fails, scar revision surgery ought to be the first choice; this simpler procedure can often achieve satisfactory outcomes and produce fewer complications. Scar revision surgery involved only the excision of the fibrotic tissue and suturing of the wound, causing less trauma to the anoderm and thus risks fewer postoperative complications than anoplasty. Most of our patients with mild anal stenosis in whom conservative treatment failed were satisfied with scar revision surgery, and had none complications or recurrences. Anoplasty is only indicated if scar revision surgery fails.

Moderate anal stenosis is defined as the ability of a lubricated index finger or medium- sized Hill-Ferguson retractor to penetrate the anus only after forceful dilatation[11]. Such patients usually require surgical intervention, as conservative management is likely to fail. In our study, 2 of the 4 patients with moderate anal stenosis reported no change in their postoperative quality of life after undergoing scar revision surgery; they still experienced strained defecation and incomplete evacuation, which we considered recurrences. Three and five patients in our study with moderate and severe anal stenosis, respectively, had previously undergone scar revision surgery before attempting diamond- shaped flap owing to recurrence; they also required adjuvant therapy such as laxatives, pain control medication, and/or self-digital dilatation. Accordingly, these findings suggest that patients with moderate anal stenosis should undergo anoplasty instead of scar revision surgery to avoid subsequent operations.

Severe anal stenosis is defined as the inability of either a lubricated little finger or a small Hill-Ferguson retractor to penetrate the anus[11]. As in patients with moderate stenosis, conservative management is not adequate for patient with severe stenosis. Moreover, scar revision surgery is not feasible owing to extensive cicatrized tissue. Therefore, we immediately opted for anoplasty for these patients. Anoplasty consists of excising the fibrotic tissue, dissecting the stricture, and increasing the dimension of the anal outlet using proximal or distal local flap advancement to restore normal anal function[20,21,25]. In our study, all patients with severe anal stenosis who underwent double diamond flap anoplasty achieved good outcomes; their postoperative quality of life improved significantly, and none required adjuvant therapy or experienced recurrence.

There are numerous procedures described in the literature regarding anoplasty for anal stenosis, and the choice of the surgery depends on the surgeon’s experience as well as the severity of the stricture[6,12,17,26]. No single procedure is superior to others, and it is difficult to evaluate the outcomes of the various techniques owing to the lack of adequate prospective trials[12]. We selected the double diamond flap anoplasty technique because of its good long-term results and low complication rates, as well as our departmental experience with this procedure. Moreover, this method is performed on both sides of the anus simultaneously, which can ameliorate the stenosis remarkably. After the anoplasty procedure, the postoperative quality of life improved greatly, and none of the patients required adjuvant therapy or experienced recurrences.

However, we found that the length of hospital stay was significantly longer in the double diamond flap anoplasty group than in the scar revision surgery group. Given that the anoplasty produced a larger operative wound, it is likely that more pain control medication is required in this group. The number of postoperative complications associated with urinary retention was also higher in the anoplasty group, even though this group experienced better performance than the scar revision surgery group in terms of quality of life improvement, recurrence rate, and the need for postoperative adjuvant therapy.

Based on our experience, we developed an algorithm for selecting the appropriate anal stenosis management methods according to severity (Figure 4). According to this algorithm, conservative management should considered first for mild anal stenosis; if non-operative approaches fail, scar revision surgery can then be performed. A simpler procedure can often achieve satisfactory outcomes and produce fewer complications. If the patient experiences recurrence after scar revision surgery, anoplasty is indicated. For patients with moderate or severe anal stenosis, conservative management or scar revision surgery may not be adequate first choices; rather, directly opting for anoplasty may be the best way to achieve satisfactory outcomes and avoid secondary operations.

There are some limitations in our study. First, some biases were inevitable because of the retrospective and single-hospital nature of this study. Second, it was small sample size because most of the patients with anal stenosis did not need surgical intervention, which were excluded in advance. Third, information on important confounders for the associated risks (e.g., smoking habits, consumption of alcohol, dietary patterns, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and many other comorbidities) were not well-recorded. Finally, it was a retrospective cohort analysis. Further large-scale prospective studies are needed to investigate these results.

Anal stenosis can be managed effectively, with the optimal method based on the condition’s severity. For mild anal stenosis, scar revision surgery can be attempted first if nonsurgical methods fail, with anoplasty performed if recurrence occurs. For moderate and severe anal stenosis, opting for anoplasty from the outset is the best option to prevent subsequent surgeries.

There are two main surgical treatments for anal stenosis: scar revision surgery and anoplasty. There were no studies comparing these two approaches, and it remains unclear which is preferrable for stenoses of different severities, including mild, moderate, and severe.

To compare the outcomes of scar revision surgery and double diamond-shaped flap anoplasty for anal stenosis.

To analyze which surgery have benefit to different severity of anal stenosis.

Patients with anal stenosis following hemorrhoidectomy procedures who were treated with either scar revision surgery or double diamond-shaped flap anoplasty at our institution between January 2010 and December 2015 were investigated and compared.

The mean operative time for scar revision surgery was significantly shorter than that for double diamond-shaped flap anoplasty. The average of length of hospital stay was also significantly shorter after scar revision surgery than after anoplasty.

Scar revision surgery may be preferable for mild anal stenosis upon conservative treatment failure. Anoplasty is unavoidable for moderate or severe stenosis, where cicatrized tissue is extensive.

Further study must conduct to analyze which surgery have benefit to different severity of anal stenosis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Gallo G, Italy; Tuncyurek O, Turkey S-Editor: Chang KL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chang KL

| 1. | Rosen L. Anoplasty. Surg Clin North Am. 1988;68:1441-1446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Handaya Y, Sunardi M. Bilateral Rotational S Flap Technique for Preventing Restenosis in Patients With Severe Circular Anal Stenosis: A Review of 2 Cases. Ann Coloproctol. 2019;221-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Casadesus D, Villasana LE, Diaz H, Chavez M, Sanchez IM, Martinez PP, Diaz A. Treatment of anal stenosis: a 5-year review. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:557-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Khubchandani IT. Anal stenosis. Surg Clin North Am. 1994;74:1353-1360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Brisinda G. How to treat haemorrhoids. Prevention is best; haemorrhoidectomy needs skilled operators. BMJ. 2000;321:582-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Habr-Gama A, Sobrado CW, de Araújo SE, Nahas SC, Birbojm I, Nahas CS, Kiss DR. Surgical treatment of anal stenosis: assessment of 77 anoplasties. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2005;60:17-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Eu KW, Teoh TA, Seow-Choen F, Goh HS. Anal stricture following haemorrhoidectomy: early diagnosis and treatment. Aust N Z J Surg. 1995;65:101-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wilson MS, Pope V, Doran HE, Fearn SJ, Brough WA. Objective comparison of stapled anopexy and open hemorrhoidectomy: a randomized, controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1437-1444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sloane JA, Zahid A, Young CJ. Rhomboid-shaped advancement flap anoplasty to treat anal stenosis. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21:159-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chiarelli M, Guttadauro A, Maternini M, Lo Bianco G, Tagliabue F, Achilli P, Terragni S, Gabrielli F. The clinical and therapeutic approach to anal stenosis. Ann Ital Chir. 2018;89:237-241. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Milsom JW, Mazier WP. Classification and management of postsurgical anal stenosis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1986;163:60-64. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Brisinda G, Vanella S, Cadeddu F, Marniga G, Mazzeo P, Brandara F, Maria G. Surgical treatment of anal stenosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1921-1928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shevchuk IM, Sadoviy IY, Novytskiy OV. [SURGICAL TREATMENT OF POSTOPERATIVE STRICTURE OF ANAL CHANNELL]. Klin Khir. 2015;20-22. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Parnaud E. Leiomyotomy with anoplasty in the treatment of anal canal fissures and benign stenosis. Am J Proctol. 1971;22:326-330. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Owen HA, Edwards DP, Khosraviani K, Phillips RK. The house advancement anoplasty for treatment of anal disorders. J R Army Med Corps. 2006;152:87-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Asfar S. Anoplasty for Post-hemorrhoidectomy Low Anal Stenosis: A New Technique. World J Surg. 2018;42:3015-3020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Katdare MV, Ricciardi R. Anal stenosis. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:137-145, Table of Contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liberman H, Thorson AG. How I do it. Anal stenosis. Am J Surg. 2000;179:325-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lagares-Garcia JA, Nogueras JJ. Anal stenosis and mucosal ectropion. Surg Clin North Am. 2002;82:1225-1231, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Duieb Z, Appu S, Hung K, Nguyen H. Anal stenosis: use of an algorithm to provide a tension-free anoplasty. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:337-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Farid M, Youssef M, El Nakeeb A, Fikry A, El Awady S, Morshed M. Comparative study of the house advancement flap, rhomboid flap, and y-v anoplasty in treatment of anal stenosis: a prospective randomized study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:790-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Maria G, Brisinda G, Civello IM. Anoplasty for the treatment of anal stenosis. Am J Surg. 1998;175:158-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pearl RK, Hooks VH 3rd, Abcarian H, Orsay CP, Nelson RL. Island flap anoplasty for the treatment of anal stricture and mucosal ectropion. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:581-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Khubchandani IT. Mucosal advancement anoplasty. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:194-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tahamtan M, Ghahramani L, Khazraei H, Tabar YT, Bananzadeh A, Hosseini SV, Izadpanah A, Hajihosseini F. Surgical management of anal stenosis: anoplasty with or without sphincterotomy. J Coloproctol. 2017;37:13-17. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shawki S, Costedio M. Anal fissure and stenosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42:729-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |