Published online Jun 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i18.6325

Peer-review started: February 3, 2022

First decision: March 23, 2022

Revised: March 29, 2022

Accepted: April 30, 2022

Article in press: April 30, 2022

Published online: June 26, 2022

Processing time: 133 Days and 6.4 Hours

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a condition characterized by increased eosinophil proliferation in the bone marrow, as well as tissue eosinophilia, often causing organ damage. The cause of the disease is unknown. Initial symptoms include fatigue, cough, shortness of breath, myalgia, angioedema, fever, and pneumonia. In addition to the respiratory symptoms, damage to the central nervous system can lead to severe seizures. Here, we report a case with pneu

A 94-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital for heart failure and bloody stools. After admission, she also showed symptoms of pneumonia. Non-contrast computed tomography of the chest showed pleural effusion and infiltrative shadows. Lower gastrointestinal endoscopy showed multiple ulcers in the sigmoid colon. Blood analyses showed marked eosinophilia (eosinophils 1760/mm3, total leukocytes 6850/mm3). Initial treatment with furosemide 20 mg/d and prednisolone 25 mg/d relieved these symptoms. However, the patient subsequently experienced localised epileptic seizures characterized by bilateral eyelid twitching and eyes rolling upwards, without generalized convulsions, and respiratory arrest occurred. Electroencephalography showed spikes and waves. Non-contrast magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed extensive peri

HES symptoms are variable and atypical, and the level and timing of eosinophilia and organ damage are often discordant.

Core Tip: Although there are diagnostic criteria for hypereosinophilic syndrome, the various degrees of organ damage and hypereosinophilia often make diagnosis difficult in clinical practice. In addition, the organ damage and blood changes do not always occur concurrently. Therefore, clinicians must consider many differential diagnoses, especially when patients present with atypical symptoms and disease course. Early initiation of treatment is no less important than an accurate diagnosis, and the balance between the two should be considered according to the patient's condition as well as the level and quality of medical resources available at the hospital.

- Citation: Ishida T, Murayama T, Kobayashi S. Pneumonia and seizures due to hypereosinophilic syndrome—organ damage and eosinophilia without synchronisation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(18): 6325-6332

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i18/6325.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i18.6325

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a marked blood and tissue eosinophilia of unknown aetiology with a variety of clinical manifestations. Since 1975, the disease has been defined by three criteria: (1) Blood eosinophilia ≥ 1500/mm3 for longer than 6 mo (or death before 6 mo associated with signs and symptoms of hypereosinophilic disease); (2) Lack of evidence for parasitic, allergic, or other known causes of eosinophilia; and (3) Presumptive signs of organ involvement, such as heart failure, gastrointestinal dysfunction, central nervous system abnormalities, fever, or weight loss[1].

However, there are several problems with these criteria. First, according to these criteria, clinicians must wait 6 mo to diagnose a patient with multiple organ involvement. Second, an increase in eosinophils does not necessarily correlate with organ damage. Some patients may have a marked increase in eosinophils but only mild symptoms, while others may have a mild increase in eosinophils but significant organ damage[2]. Therefore, two diagnostic criteria have now been proposed to replace the classic three: (1) Blood eosinophilia of greater than 1500/mm3 on at least two occasions or evidence of prominent tissue eosinophilia associated with symptoms and marked blood eosinophilia; and (2) Exclusion of secondary causes of eosinophilia, such as parasitic or viral infections, allergic diseases, drug-induced or chemical-induced eosinophilia, hypoadrenalism, and neoplasia[3]. However, this revision of the diagnostic criteria does not solve all the problems in the diagnosis and treatment of HES. We anticipate that this case will aid in the diagnosis and treatment of similar cases.

A 94-year-old Asian woman presented to our hospital for dyspnoea and wet cough. She also had abdominal pain and bloody stools. She was admitted to our hospital with a diagnosis of heart failure and sigmoid colon ulceration (day 1).

Her respiratory distress started during the night 1 d before presentation. It improved after 1 h and was still mild over the next morning and evening hours. However, 22 h later, her symptom got worse again during the night.

The patient had no chronic illnesses such as hypertension, diabetes, or asthma, and no history of cancer. She was a non-smoker and did not habitually drink alcohol. She had a well-balanced diet and lived a healthy lifestyle.

There was no specific history.

The patient was 148 cm tall, weighed 42 kg, and her vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 111/43 mmHg; pulse 90/min; respiratory rate 14/min; and SpO2 98% (room air). On chest auscultation, her heart rhythm was regular and no heart murmur was found. However, auscultation of respiratory sounds found wheezing. Her abdomen was flat and soft and abdominal auscultation found neither increased nor decreased intestinal peristalsis. There was no rebound tenderness or abdominal guarding. However, there was intermittent and spontaneous abdominal pain and bloody stools. Her eyelid conjunctiva did not show jaundice or pallor. Her oral and nasal cavities and skin surfaces showed no abnormal findings. Her upper limbs showed no abnormalities. However, her lower extremities showed indurated oedema.

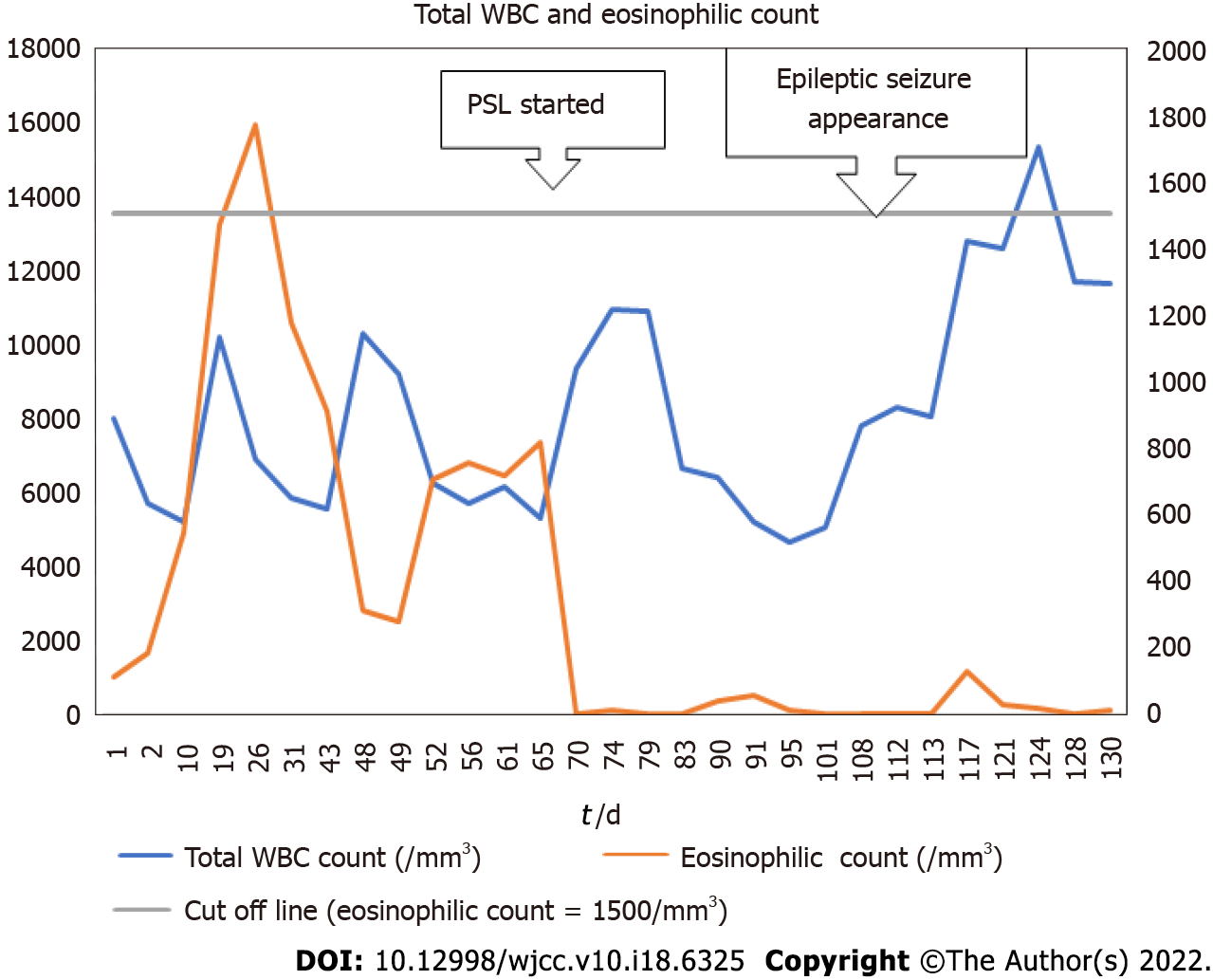

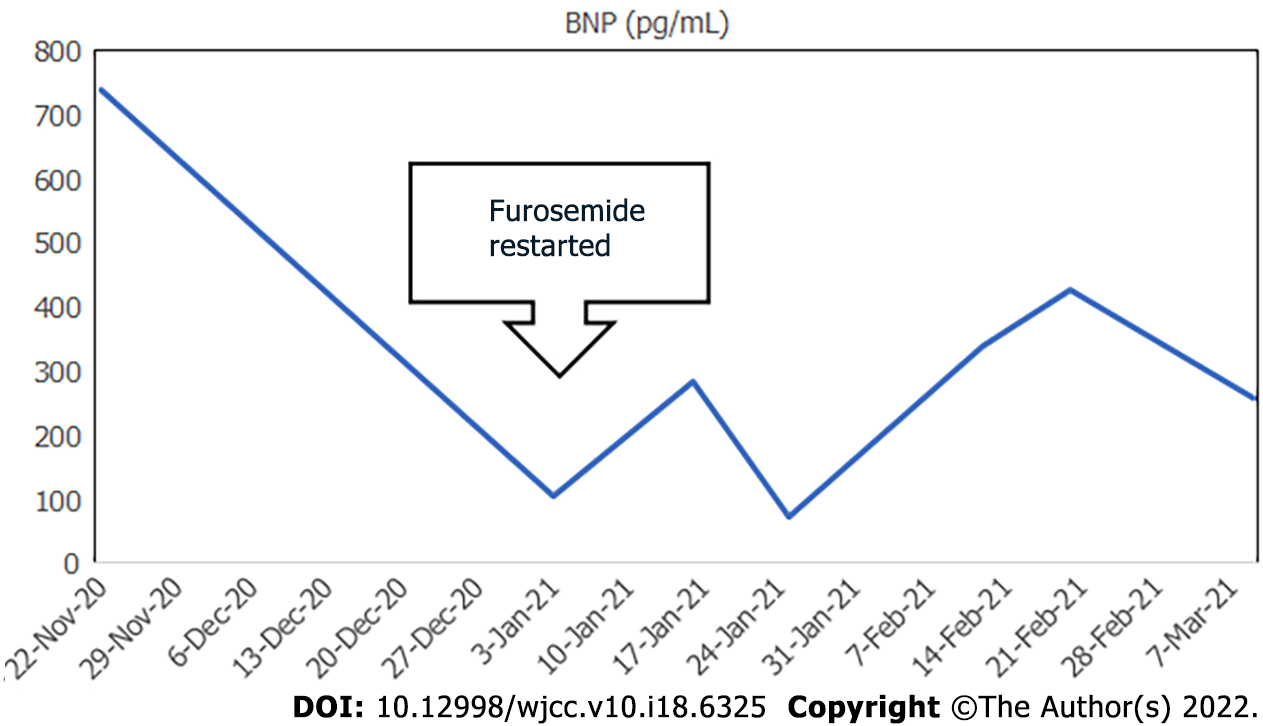

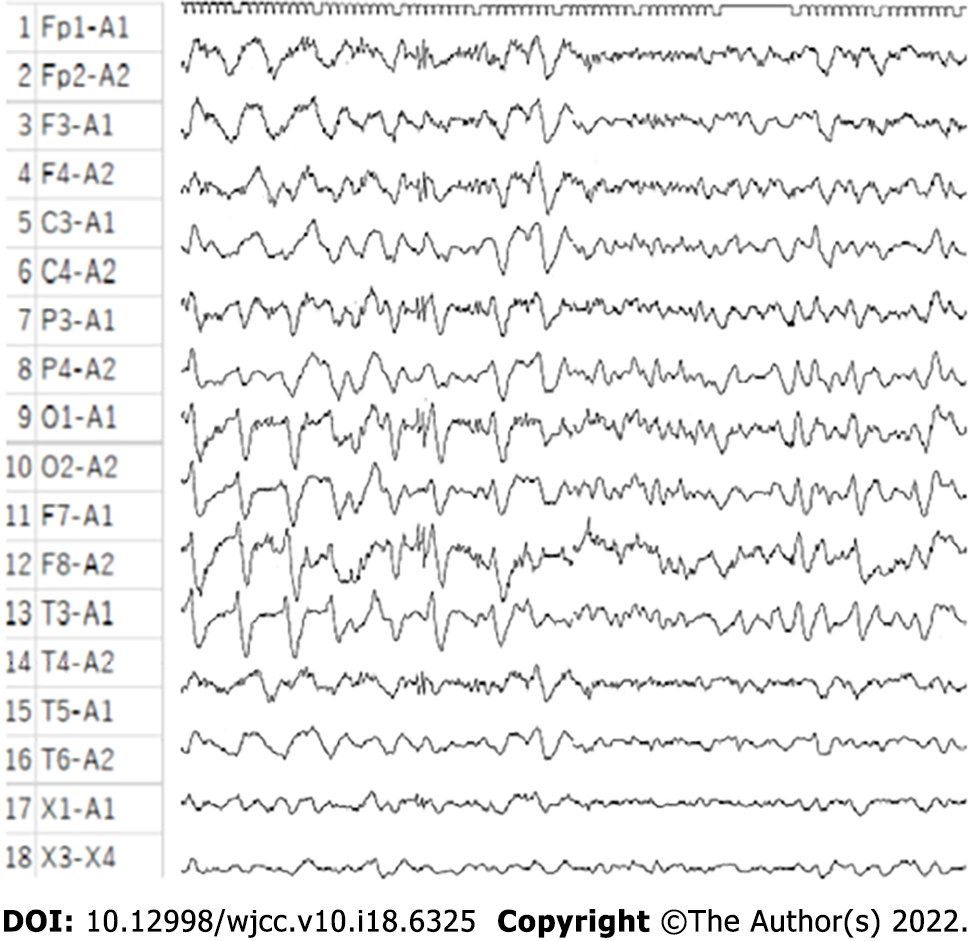

On day 1, her rapid antigen tests using a throat swab were negative for influenza A and B and COVID-19. Her electrocardiogram (ECG) showed no abnormalities on admission and on loss of consciousness on day 108. In her blood analyses, there were no abnormalities in the electrolyte, glucose, lipid, liver function, and renal function parameters. The antinuclear antibody (ANA) titre at 1:40 serum dilution was positive but staining patterns at 1:40 serum dilution was negative for homogeneous, discrete speckled, speckled, nucleolar, and peripheral staining. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and HIV tests were negative. On day 32, the patient’s IgE level was slightly high at 237 IU/mL (normal: 27.54–138.34), but her IgG, IgA, and IgM levels were normal. Blood analyses also showed that eosinophils and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels were high. The highest values for each were 1760/mm3 on day 26 for eosinophils and 738.1 pg/mL on day 1 for BNP (Figures 1 and 2). The blood and sputum taken on day 26 were negative on culture for bacteria or fungi and no parasites were found. However, on day 109, blood culture was positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis, and the β-D-glucan level was high (316.0 pg/mL). On day 128, blood tests showed normal levels of ammonia. The patient’s post-consciousness EEG showed spikes and waves in Fp1, F1, C3, P3, and O1 (Figure 3). Her echocardiogram showed no thrombi in the atria or ventricles.

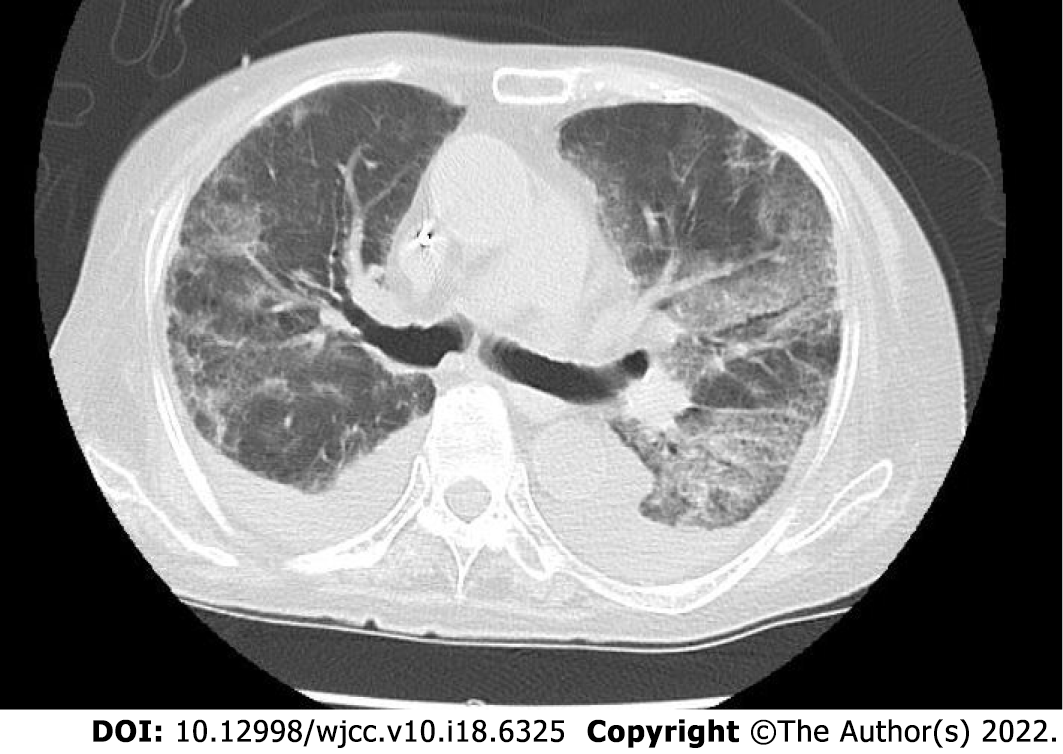

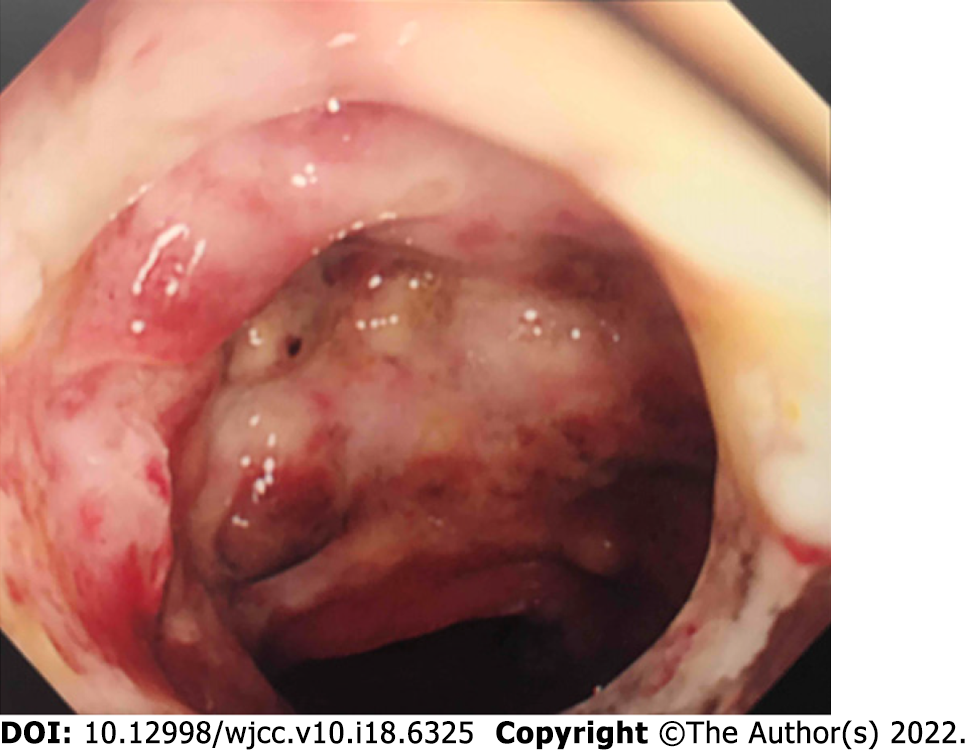

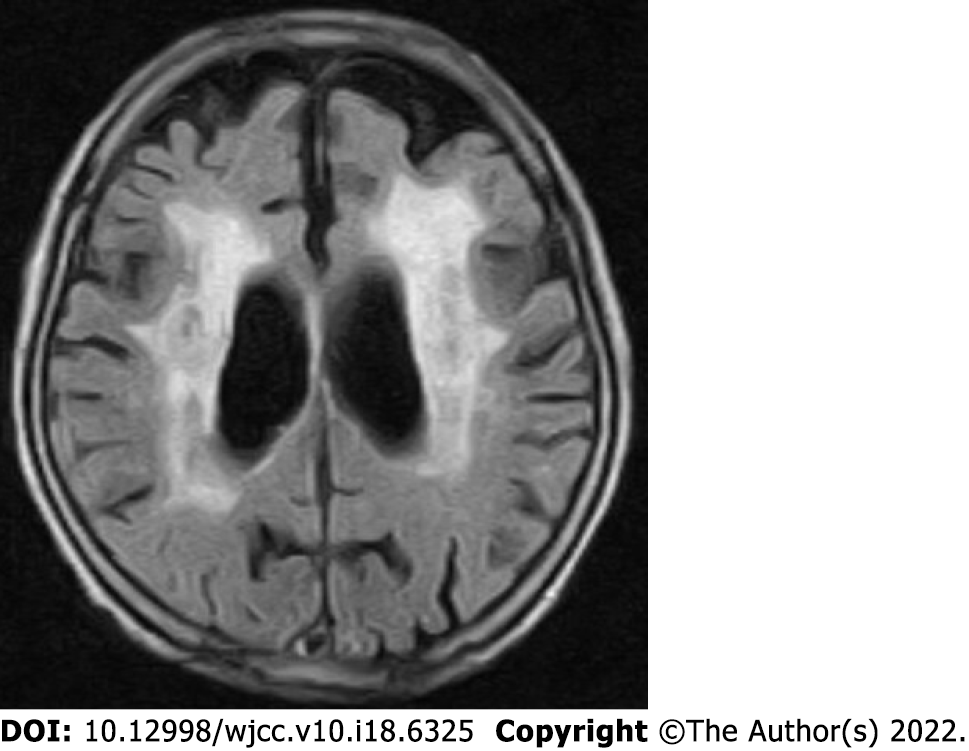

Non-contrast computed tomography imaging of the patient’s chest showed bilateral pleural effusions and infiltrative shadows (Figure 4). Her gastrointestinal endoscopy showed multiple ulcers in the sigmoid colon (Figure 5). Histopathological examination showed colonic gland prolapse, vitrification of the stroma, and an infiltration of inflammatory cells, but no evidence of malignant transformation. Non-contrast magnetic resonance imaging of the patient’s head showed extensive periventricular hyperintensity (Figure 6).

The patient’s eosinophils in the blood tests exceeded 1500/mm3 only once, but she had high eosinophils multiple times without meeting this threshold. Additionally, it was clear that the eosinophilic infiltrate was causing serious damage to the nervous, respiratory, cardiovascular, and digestive systems. We should not have delayed the initiation of her treatment any longer to meet the classical diagnostic criteria. Biopsies of organs other than her sigmoid colon were considered for a more precise examination and imatinib initiation was considered for more effective treatment, but both were too invasive for the elderly patient. Given that she and her family did not wish to undergo these tests and treatments, we did not pursue these options. Although Japan is a country with some of the richest medical resources in the world, the hospital where the patient was admitted had no intensive care unit or specialists in collagen diseases and autoimmune diseases, and the same is true for other similar rural hospitals. The use of limited medical resources is an important issue in this country as in the rest of the world.

The patient was diagnosed with epileptic seizures and pneumonia caused by HES.

In addition to rehabilitation, the patient was treated with furosemide for heart failure, ceftazidime and vancomycin and fungard and PSL for pneumonia and levetiracetam (LEV) for seizures.

Furosemide 20 mg/d for 10 d from the day of admission (day 1) relieved her congestive heart failure symptoms for a period of time. A diet suitable for digestion and absorption made her bloody stools and abdominal pain disappear. Rehabilitation, including gait training and flexibility exercises to prevent loss of range of motion and contractures throughout the body, was also initiated. However, from day 56, her congestive heart failure symptoms recurred, and pneumonia also appeared. Treatment with 20 mg/d furosemide was restarted from that day, but without effect. Ceftazidime 2 g/d was also ineffective in treating the pneumonia. On day 68, the patient was diagnosed with HES and treatment with pre

First, we will discuss diagnosis of HES. As mentioned at the beginning of this report, the diagnostic requirement for HES is a blood eosinophil count ≥ 1500/mm3 for at least 6 mo according to the classical diagnostic criteria or measured at least twice according to the diagnostic criteria proposed by Simon et al[3]. In this case, neither of these criteria were met at the time the diagnosis was made. In our case, the patient’s blood eosinophil count exceeded 1500/mm3 only once and this did not necessarily coincide with the most severe period of organ damage. Some clinicians suggested that we should have waited until her eosinophil count had risen again and her symptoms had worsened before deciding on a diagnosis. However, as stated in the Multidisciplinary Expert Consultation, we needed to start her treatment as soon as possible. This was considered a higher priority than meeting the strict diagnostic criteria. In addition, the disease course in this case meets the criterion of "or death before 6 mo associated with signs and symptoms of hypereosinophilic disease" listed in the supplementary information in the classical criteria[3]. Heart failure, sigmoid colon ulceration, pneumonia, and epilepsy signified damage to each of these organs in our patient. Therefore, the diagnosis of HES in this case was appropriate. With regard to treatment, the focus is on PSL. As is well known, PSL is a drug that needs to be tapered off, not stopped abruptly. Furthermore, a longer PSL treatment course is commonly required for eosinophilic pneumonia. However, in this case, given the early decline in the eosinophil count after initiation of PSL therapy, perhaps it should have been tapered or stopped earlier.

Next, we would like to discuss the diagnosis and treatment of epilepsy. Common causes of loss of consciousness in older people include heart disease, autonomic disorders, other conditions such as anaemia, ischaemia and varicose veins, or anticholinergic drugs[5]. Our patient had congestive heart failure at the time of admission, but her condition improved. She did not have any blood clots identified that could have caused cerebral embolism. Her vital signs, including blood pressure and ECG, were normal. Therefore, it was considered unlikely that the loss of consciousness was due to circulatory problems. Her post-consciousness electroencephalogram (EEG) suggested that there were epileptic discharges around the left anterior frontal lobe, motor cortex, central sulcus, sensory cortex, and visual cortex. The rather unremarkable EEG findings compared with the clinical findings may be because this EEG was done after the LEV treatment was started. The epileptic discharges may have been more intense before the administration of antiepileptic drugs. We were not able to do rapid or continuous monitoring EEG at our hospital. In diagnosing and treating her epilepsy, we were forced to prioritise life-saving treatment over rigorous diagnosis.

Regarding the seizure type, her epilepsy was most likely a complex partial seizure. Complex partial seizures are more likely to occur in older adults and cause disorientation, but they do not cause tonic or clonic seizures[6]. The fact that LEV treatment was effective in preventing the seizure symptoms was also one of the reasons for the diagnosis. However, the presence of eyelid twitching also suggests that her seizure type may have been absence seizures. Absence seizures are generally more common in young children and have a shorter duration of disorientation. However, if the seizure is an atypical absence seizure, the disturbance of consciousness may be prolonged. In Japan, LEV may be administered at doses of up to 3000 mg/d. However, in this case, the patient was elderly, and it was feared that increasing the dose of LEV might cause side effects such as malignant syndrome. The LEV dose was not increased because there were no obvious epileptic seizures after the start of LEV at a dose of 1000 mg/d. In this case, the patient’s loss of consciousness was prolonged even after an intr

While all ANA staining patterns were negative, the ANA titre was positive at 1:40 dilution. This result indicates that our patient may have had a collagen disease. Therefore, we needed to differentiate the collagen diseases with eosinophilia granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EPGA) and polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), from HES. EPGA, formerly known as Churg–Strauss syndrome, is characterised by asthma, eosinophilia of the blood and tissues, and small vessel vasculitis. The clinical symptoms are variable but can be divided into two main subtypes: The "vasculitis" type, which is positive for ANCA and shows glomerulonephritis, purpura, and inflammation of multiple peripheral nerves. The other is the "eosinophilic" type, which is negative for ANCA but is characterised by a markedly high level of eosinophils and damage in the lungs and myocardium[8]. This case is similar to the "eosinophilic" type, but EPGA is less likely to cause central nervous system damage such as seizures.

PAN is a vasculitis that targets medium-sized arteries and leads to multi-organ failure. The target organs include the heart and the gastrointestinal tract. We note that damage to the central nervous system has also been reported[9]. However, damage to the lungs has rarely been reported[10]. The present case is not typical but is similar to both EPGA and PAN. However, the pathological findings in the sigmoid colon did not show the features of either of these diseases.

In terms of brain imaging findings, the differential diagnosis in this case also includes cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). The Modified Boston Criteria for CAA are based on imaging and pathological findings. The disease can be classified as: (1) Definite CAA; (2) Probable CAA with supporting pathology; (3) Probable CAA; and (4) Possible CAA. The novelty of this criteria is that (3) and (4) do not require a pathological examination[11]. In this case, at the request of the patient and her family, no pathological examination of the brain tissue was performed after her death. Generally, the hallmark of CAA on brain imaging is multiple sporadic lesions confined to the cerebral cortex, cortico-subcortical junction grey matter, and subcortical white matter. However, some subtypes of CAA, such as cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation (CAA-ri), present with mass-like lesions as in this case[12]. CAA-ri is known to respond well to treatment with steroids and immunosuppressive drugs. In this case, treatment was given with the expectation that the patient might be diagnosed with CAA-ri. There is a report that CAA-ri can cause seizures[13], which seems to be consistent with the symptoms in this case. However, there are no previous studies on its frequency. Similar cases need to be studied in the future.

HES can cause damage to many organs and has an undulating disease course. Therefore, HES must be differentiated from other diseases such as EPGA, PAN, and CAA. In this case, the diagnosis was more difficult because of the time lag between the various clinical symptoms and the eosinophilia. The focus of treatment was to determine the appropriate dose and duration of PSL and LEV therapy. We conclude that this case report can be used as a reference for the diagnosis and treatment of similar cases.

This study was conducted at Iwanai Kyokai Hospital (209-2, Aza-Takadai, Iwanai-cho, Iwanai-gun, Hokkaido 045-0013, Japan). We are grateful to the patient who gave her consent to take part in this study. We would also like to thank Dr. Kawasaki, Dr. Yamazaki, and Dr. Kuroda in the Department of Internal Medicine at Iwanai Kyokai Hospital for their help and support. We thank Leah Cannon, PhD, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Clinical neurology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fazilat-Panah D, Iran; Shuang WB, China S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Chusid MJ, Dale DC, West BC, Wolff SM. The hypereosinophilic syndrome: analysis of fourteen cases with review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1975;54:1-27. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Klion AD, Bochner BS, Gleich GJ, Nutman TB, Rothenberg ME, Simon HU, Wechsler ME, Weller PF; The Hypereosinophilic Syndromes Working Group. Approaches to the treatment of hypereosinophilic syndromes: a workshop summary report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1292-1302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Simon HU, Rothenberg ME, Bochner BS, Weller PF, Wardlaw AJ, Wechsler ME, Rosenwasser LJ, Roufosse F, Gleich GJ, Klion AD. Refining the definition of hypereosinophilic syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:45-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8080] [Cited by in RCA: 8083] [Article Influence: 158.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Berrut G, Hommet C, Beauchet O. [Loss of consciousness in the elderly]. Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil. 2007;5:101-120. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Collins NS, Shapiro RA, Ramsay RE. Elders with epilepsy. Med Clin North Am. 2006;90:945-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chamberlain JM, Kapur J, Shinnar S, Elm J, Holsti M, Babcock L, Rogers A, Barsan W, Cloyd J, Lowenstein D, Bleck TP, Conwit R, Meinzer C, Cock H, Fountain NB, Underwood E, Connor JT, Silbergleit R; Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network investigators. Efficacy of levetiracetam, fosphenytoin, and valproate for established status epilepticus by age group (ESETT): a double-blind, responsive-adaptive, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1217-1224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Trivioli G, Terrier B, Vaglio A. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: understanding the disease and its management. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59:iii84-iii94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | de Boysson H, Guillevin L. Polyarteritis Nodosa Neurologic Manifestations. Neurol Clin. 2019;37:345-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | De Virgilio A, Greco A, Magliulo G, Gallo A, Ruoppolo G, Conte M, Martellucci S, de Vincentiis M. Polyarteritis nodosa: A contemporary overview. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15:564-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Greenberg SM, Charidimou A. Diagnosis of Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy: Evolution of the Boston Criteria. Stroke. 2018;49:491-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 43.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Silek H, Erbas B. Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy Related Inflammation Presenting as Steroid Responsive Brain Mass. Turk Neurosurg. 2020;30:629-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ii Y, Tomimoto H. [Inflammatory cerebral amyloid angiopathy]. Brain Nerve. 2015;67:275-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |