Published online Jun 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i18.6234

Peer-review started: November 26, 2021

First decision: January 24, 2022

Revised: March 15, 2022

Accepted: April 29, 2022

Article in press: April 29, 2022

Published online: June 26, 2022

Processing time: 202 Days and 12.1 Hours

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) is a rare protein-losing enteropathy characterized by abnormally dilated lymphatic structures, resulting in leakage of lymph (rich in protein, lymphocytes, and fat) from the intestinal mucosal and submucosal layers and thus hypoproteinemia, lymphopenia, hypolipidemia, and pleural effusion.

A 19-year-old Chinese male patient complained of recurrent limb convulsions for the last 1 year. Laboratory investigations revealed low levels of calcium and magnesium along with hypoproteinemia and high parathyroid hormone levels, whereas gastroscopy exhibited chronic non-atrophic gastritis and duodenal lymphatic dilatation. Subsequent gastric biopsy showed moderate chronic inflammatory cell infiltration distributed around a small mucosal patch in the descending duodenum followed by lymphatic dilatation in the mucosal lamina propria, which was later diagnosed as PIL. The following appropriate medium-chain triglycerides nutritional support significantly improved the patient’s symptoms.

Since several diseases mimic the clinical symptoms displayed by PIL, like limb convulsions, low calcium and magnesium, and loss of plasma proteins, it is imperative to conduct a detailed analysis to avoid any misdiagnosis while pinpointing the correct clinical diagnosis and simultaneously ruling out other clinical aspects in the reported cases without any past disease history. A careful assessment should always be made to ensure an accurate diagnosis in a timely manner so that the patient can be delivered quality health services for a positive health outcome.

Core Tip: In this case report, a 19-year-old Chinese male patient complained of recurrent limb convulsions for 1 year. Laboratory investigations revealed low levels of calcium and magnesium along with hypoproteinemia and high parathyroid hormone levels, but the patient had no limbs edema, which is rear in primary intestinal lymphangiectasia cases. Differential diagnosis is difficult in such case. Careful analysis and examination results finally enabled the patient to receive effective treatment after a definite diagnosis.

- Citation: Cao Y, Feng XH, Ni HX. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia presenting as limb convulsions: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(18): 6234-6240

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i18/6234.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i18.6234

Intestinal lymphangiectasia (IL) is a rare protein-losing enteropathy[1], characterized by small intestinal lymphatic drainage obstruction, chylous ascites, and villi distortion that further cause lymphatic congestion and elevate the lymphatic pressure, thereby resulting in leakage of lymph liquid into the small intestinal lumen. IL can be categorized into two forms, primary IL (PIL) and secondary IL (SIL). PIL, first reported by Milroy in 1892, is more common in children and adolescents, though rarely, it can also occur in adults and has a tendency to occur sporadically with an unknown etiology. Waldmann et al[2] in 1961 after demonstrating protein loss quantification by 51Cr-labelled albumin revealed that the lymphatic vessels present in the mucosal and submucosal layers of the small intestine were abnormally dilated to varying degrees. Hence, this diagnosis came into existence.

The incidence of PIL is likely to be related to lymphatic dysplasia in infants which is more frequently diagnosed in children (less than 3 years old), but also in adolescents and even elderly cases[3]. Although in most cases lymphatic dilation is typically seen in the descending duodenum, lymphatic dilation in the small intestine is usually mild and segmental, and secondary causes should be excluded. In this case report, a 19-year-old adult man complained of limb convulsions for the past 1 year, which after further investigations, was later identified as PIL. The following medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) nutritional support improved the patient’s condition.

A 19-year-old Chinese male patient complained of recurrent limb convulsions for the past 1 year.

The patient experienced recurrent limb convulsions and numbness with an unknown medical history in the absence of any aggravating factors like joint inflammation, edema, headache, dizziness, nausea and vomiting, abdominal distention, pain, or diarrhea, leading to a gradual weight loss by five kilograms, but due to the ignorance of the patient as well as his family, no further treatment was initiated. But 1 wk ago, his symptoms, comprising of limb convulsions and numbness, got so aggravated that he visited the community hospital in April 2021 for a thorough examination that was preceded by laboratory investigations that showed reduced levels of blood calcium 1.50 mmol/L (1.95 mmol/L after correction, normal range: 2.08-2.6 mmol/L), magnesium 0.49 mmol/L (normal range: 0.75-1.02 mmol/L), potassium 3.38 mmol/L (normal range: 3.5-5.5 mmol/L), and albumin 17.27 g/L (normal range: 40-55 g/L) while displaying increased parathyroid hormone (PTH) 113.0 pg/mL (normal range: 15-65 pg/mL). The patient had blood phosphorus at 1.12 mmol/L, TSH at 2.5 mIU/L, and a positive fecal occult blood test (FOBT). He was supplemented with albumin, calcium gluconate injections, and potassium magnesium aspartate. Henceforth, the persistent symptoms like limb convulsions and numbness were relieved after symptomatic treatment for 1 week. He went to the Endocrinology Department of our hospital for a further definite diagnosis.

The patient was healthy until the age of 18, with no trauma or any history of tumor.

The patient was born by spontaneous labor at term, was breastfed in infancy, and had normal physical and cognitive development as his peers along with good academic performance. However, he had a history of hemorrhoids but did not have any long-term chronic abdominal pain and diarrhea in adolescence. His parents were healthy while denying any history of familial genetic disease, psychosis, and infection in the older family generations.

The patient’s height was 174 cm, weight was 52 kg, and body mass index was 17.18 kg/m2. He did not exhibit widening of either eye distance or base of the nose-bridge and small external ear while his abdomen was flat and soft, with no abdominal tenderness or rebound pain, non-palpable liver and spleen, normal bowel sounds, and limb strength. Especially, no concave edema was found in both lower limbs, whereas the Babinski’s sign, Chvostek's sign, and Trousseau’s sign were negative (Figure 1).

The results of blood biochemistry were: Calcium 2.37 mmol/L (normal range: 2.08-2.6 mmol/L), magnesium 0.73 mmol/L (normal range: 0.75-1.02 mmol/L), potassium 4.19 mmol/L, phosphorus 1.19 mmol/L, parathyroid hormone 16.7 pg/mL (normal range: 15-65 pg/ mL), and albumin 25.2 g/L (normal range: 40-55 g/L). The FOBT was positive (1+).

The results of routine blood tests were: White blood cell count 3.8 x 109/L, lymphocyte count 0.41 x 109/L (normal range: 1.1 x 109/L-3.2 x 109/L), and lymphatic percentage 10.4% (normal range: 20%-50%)

The results of fat-soluble vitamin tests were: Vitamin A 0.28 μg/mL (normal range: 0.30-0.70 μg/mL), 25-hydroxyvitamin D 5.28 ng/mL (< 20 ng/mL suggesting deficiency), vitamin E 4.49 μg/mL (normal range: 0.30-0.70 μg/mL), and vitamin K1 0.12 ng/mL (normal range: 0.20-2.50 ng/mL).

The results of immunological tests were: Immunoglobulin (Ig)A 0.49 g/L (normal range: 0.82-4.53 g/L), IgG 1.44 g/L (normal range: 7.51-15.6 g/L), IgM 0.18 g/L(normal range: 0.46-3.04 g/L), complement (C)3 0.67 g/L (normal range: 0.79-1.52 g/L), C4 0.15 g/L (normal range: 0.16-0.38 g/L); transferrin 1.42 g/L (normal range: 2.0-3.6 g/L); copper orchid protein 10.70 mg/dL (normal range: 22-58 mg/dL); B cell count (CD19+) 38 x 106/L (normal range: 50 x 106/L-670 x 106/L), T cell count (CD3+CD45+) 179 x 106/L(normal range: 470 x 106/L-3270 x 106 /L), T helper count (CD3+CD4+) 46 x 106/L (normal range: 200 x 106/L-1820 x 106/L), T inhibitory cell count (CD3+CD8+) 120 x 106/L (normal range: 130 x 106/L-1350 x 106/L); the number of NK cells was normal.

The HIV + RPR panel was Negative, and blood and stool IBD screening showed no obvious abnormalities.

The patient had normal liver and kidney function, thyroid function, thyroglobulin, thyroglobulin antibody, and thyroid peroxidase antibody. The results of endocrine tests were: ACTH: 8 am 13.2 ng/L, 4 pm 12.6 ng/L, 0 am 5.3 ng/L; cortisol: 8 am 174.3 nmol/L, 4 pm 102.7 nmol/L, 0 am < 25 nmol/L; follicle stimulating hormone 5.98 IU/L, luteinizing hormone 7.74 IU/L, estradiol 98.38 pmol/L, testosterone 27.56 nmol/L; insulin-like growth factor-1 208 μg/L, and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 4.8 mg/L. Tumor markers, ANA spectrum, ANCA, rheumatoid factor, ESR, and hepatic fibrosis were all in the normal range. Urine immunoglobulin light chain, 24-h urine protein, and 24-h urine calcium within the normal range.

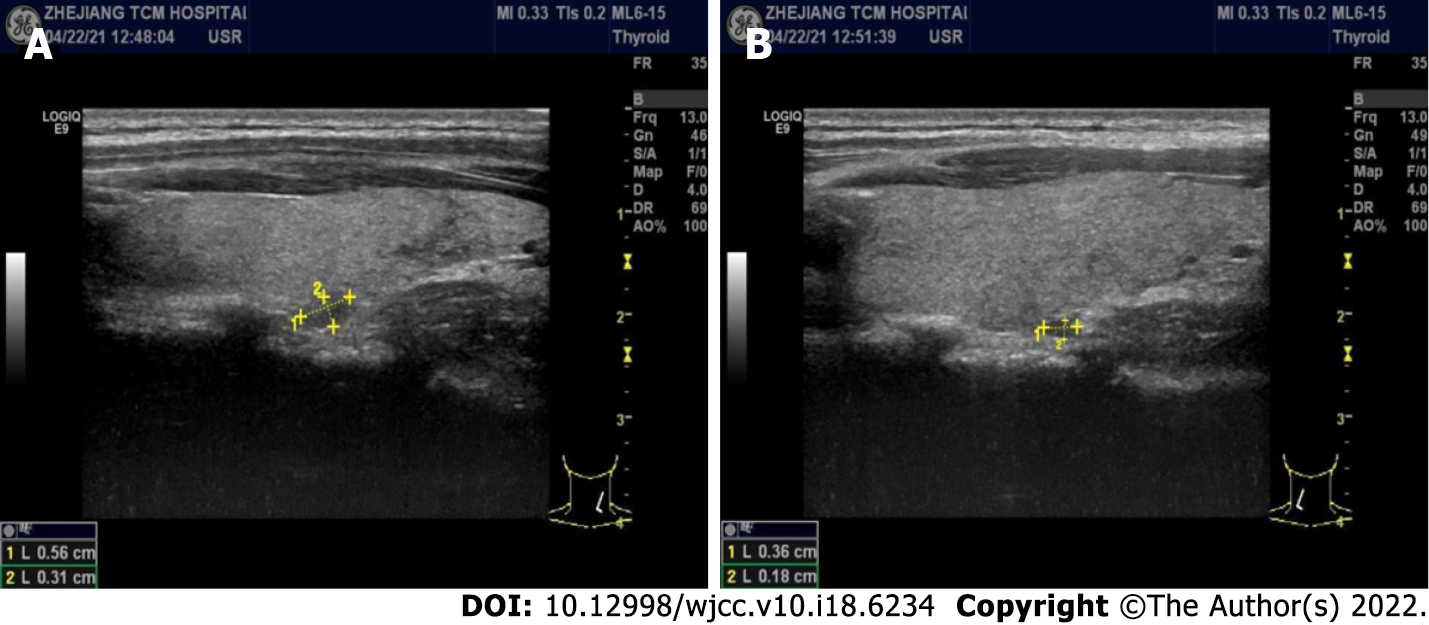

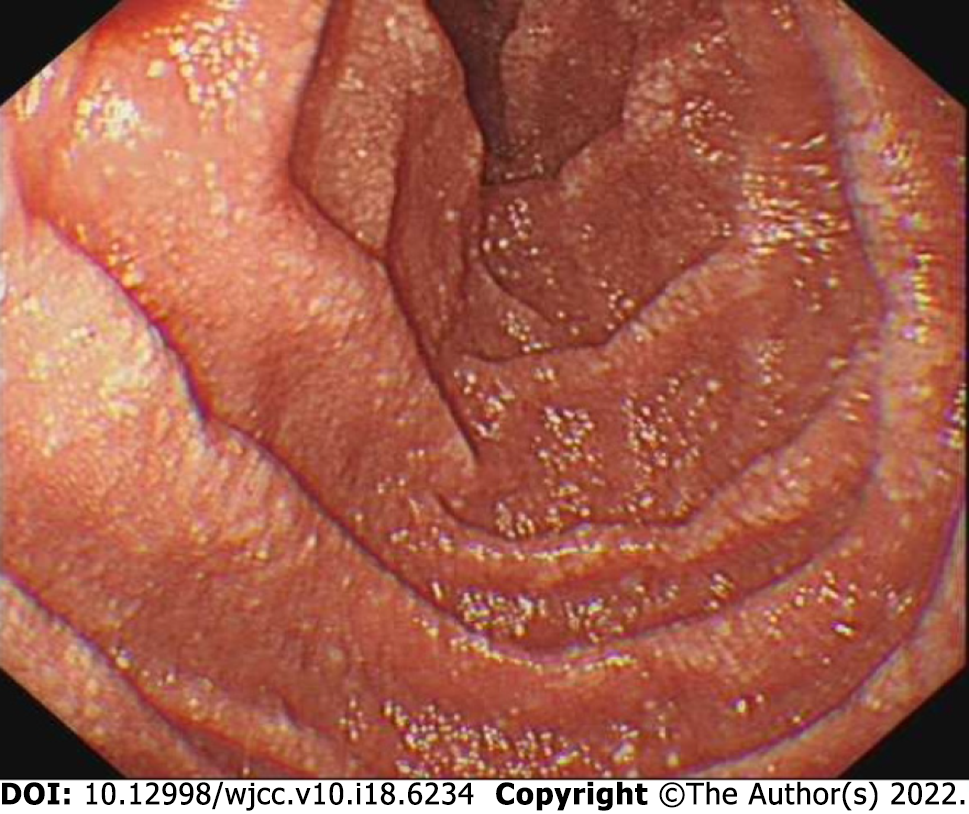

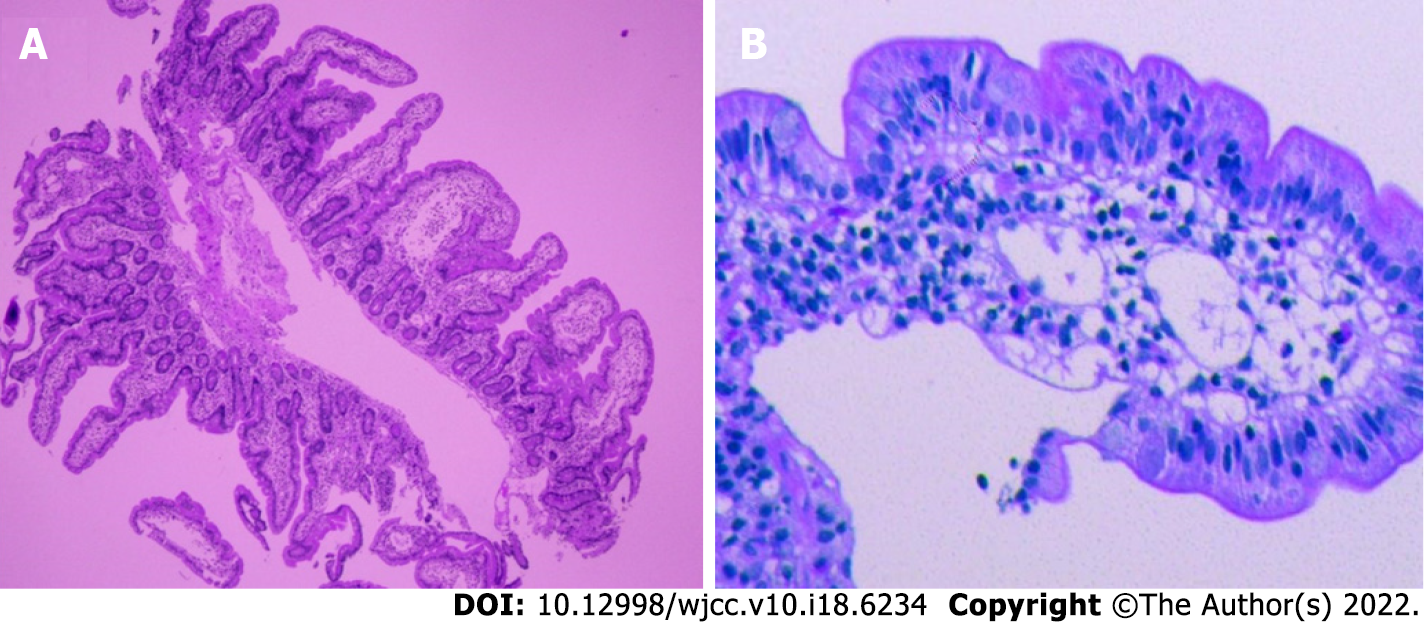

B-mode ultrasound imaging of the parathyroid gland revealed a hypo-echoic nodule with a clear boundary and regular shape along with few blood vessels (Figure 2). An MRI examination exhibited no obvious abnormality while an abnormal-signal nodule was found in front of the right middle abdominal psoas muscle, which was considered as an enlarged lymph node followed by a scanty exudate at the abdominal and pelvic cavity, along with cortical soft tissue edema. Capsule endoscopy showed the flat composition of duodenal mucosal villi with no obvious abnormality in the jejunal or ileal mucosa. Gastroscopy exhibited chronic non-atrophic gastritis and duodenal lymphatic dilatation (Figure 3). Subsequent gastric biopsy showed moderate chronic inflammatory cell infiltration distributed around a small mucosal patch in the descending duodenum followed by lymphatic dilatation in the mucosal lamina propria (Figure 4).

The patient was treated with a low-fat, high-protein, light diet which contains 1800 calorie each day, and with MCT powder supplement, calcium supplement, and vitamin D supplement.

The patient returned to the clinic 3 mo later, and showed no symptoms of convulsion of the limbs. Meanwhile, blood calcium and albumin in the laboratory examination increased compared with the values before.

The clinical manifestations of PIL are diverse as they may cause dilatation of the intestinal lymphatic vessels, leading to loss of lymph fluid into the gastrointestinal tract. While it is mainly characterized by edema of varying degrees, it can also manifest as pleural effusion, pericarditis, chylous ascites, diarrhea, fat vitamin deficiency, weight loss, and other symptoms occurring in severe cases. In our case, due to unknown past medical history, diagnosing and providing prompt treatment were initially challenging as there was no clear history of diarrhea and abdominal pain, limb convulsions, or disease symptoms in childhood. The now obvious limb convulsions first appeared when the patient was 18 years of age and manifested themselves as hypocalcemia, hypomagneemia, and hypoproteinemia, along with elevated PTH levels. Due to similar propensity and characteristics, this disease can easily mimic pseudohypoparathyroidism (PHP) and some other similar diseases in internal medicine, which might lead to misdiagnosis and a plethora of unpleasant side effects. Therefore, the foremost thing that is recommended is to reach a definite diagnosis for a positive outcome.

Laboratory tests at presentation suggested hypocalcemia, hypomagneemia, hypoproteinemia, and lymphocytopenia. Further investigation revealed elevated PTH, decreased vitamin D, low immunoglobulinemia, and positive FOBT. First, the patient had hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia, and the convulsions of the limbs were relieved by treatment with calcium gluconate and potassium magnesium aspartate. Elevated PTH and hypoproteinemia gave us the impression of renal insufficiency, but subsequent negative results of renal function and urinary protein precluded this diagnosis. Laboratory tests revealed normal liver function and negative rheumatoid and tumor markers, so we focused on the parathyroid gland. According to B-ultrasonography, hyperplasia of nodules, elevated PTH, and hyp

PHP is a genetic disease in which peripheral cells are resistant to PTH[4]. The central link of the disease is PTH resistance, which leads to high blood phosphorus and activation disorders of 25-(OH)D3, eventually leading to hypocalcaemia. Although this disease is common in women but more severe in men, the reported patients showed symptoms at 2 years of age, which became more obvious after the age of 10 but can rarely be seen in people aged 20 years or above. Tetany and intracranial calcification are usually the most common clinical manifestations and imaging features of PHP. PHP patients with vitamin D deficiency have more severe clinical symptoms, and vitamin D deficiency increases the risk of autoimmune disease. Vitamin D is mainly synthesized in the skin of the body, and then converted into 25-(OH)D by the hydroxylation of 25-hydroxylase (CYP27A1) in the liver, which is the main form of vitamin D in the circulation. 25-(OH)D binds to vitamin D binding protein into the blood circulation and generates active metabolite 1,25-(OH)2D under the catalysis of renal 1αhydroxylase (CYP27B1). 1,25-(OH)2D acts on the intestine, kidney, and bone to regulate the metabolism of calcium and phosphorus. In the small intestine, 1,25-(OH)2D promotes the absorption of calcium and phosphorus, and serum 25-(OH)D is inversely proportional to PTH. When the serum 25-(OH)D level decreases, blood calcium decreases and PTH increases. The increased PTH stimulates the activity of 1αhydroxylase and increases the efficiency of 25-(OH)D conversion to 1,25-(OH)2D. In addition, PTH also normalizes blood calcium levels by stimulating osteoclast proliferation, and increasing bone absorption and calcium release. In this case, the patient had low calcium, with a compensatory increase of PTH, and the blood phosphorus level was within the normal range during the onset. The reexamination of PTH returned to normal during the further correction of low calcium, proving that it was a secondary factor, so PHP could be excluded. Parathyroid nodules were also considered nonfunctional.

Considering the possibility of protein-loss enteropathy, subsequent gastroscopy revealed duodenal lymphatic dilation, confirming our assessment. IL could be divided into primary and secondary types. Primary IL is a congenital lesion with an ambiguous incidence rate and disease mechanism though occurring more sporadically despite the involvement of genetic factors in the pathogenesis[5], whereas secondary IL can be caused by several factors as autoimmune diseases (i.e., Crohn’s disease[6], ulcerative colitis[7], and Henoch-Schonlein purpura), tumors (such as non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma[8]), infections (such as rotavirus), portal hypertension, constrictive pericarditis[9], trauma, or surgical injury[10]. In our case report, Crohn’s disease was first excluded as FOBT results showed 1+ repeatedly while blood and stool IBD screening was negative. As the patient had a previous history of hemorrhoids, the anorectal department considered it as hemorrhoid bleeding after the consultation.

Some PIL patients are found with abnormal immune system responses in which the decrease of B cells is manifested by the decreasing IgG, IgA, and IgM levels[11]. Some previous studies also reported that PIL patients’ peripheral blood samples contain a very low number of CD4+ T cells[12] that were significantly lesser than B cells, while the remaining CD4+ T cells became highly differentiated and sensitized, thereby showing poor proliferation[13]. It was also observed that the patient’s T lymphocytes kept on decreasing in varying degrees in this case. Further evidence will be necessary to determine whether T lymphocytes mediate the immune functions in the intestine, and further lead to the occurrence and development of the disease.

Since the PIL etiology is ambiguous and standardized treatment is inadequate, a study by Alfano et al[14] revealed that the primary goal of PIL treatment is to reduce protein loss, maintain circulating blood volume, and inhibit excessive tissue fluid production, thereby indicating that pharmacological treatment is the first-line treatment prescribed in the clinic. In the gastrointestinal tract, MCT is decomposed into glycerol and medium-chain fatty acids that are directly absorbed in the portal vein blood flow by small intestinal epithelial cells without going through lymphatic vessels, thus reducing the pressure in lymphatic vessels, lymph leakage, and protein loss. Incorporating an MCT-rich diet in daily life could significantly improve the symptoms and long-term mortality of PIL patients, although it might not improve the inherent lymphatic abnormalities; thus, the patients might need to take the required medications for a longer period of time.

Based on this case, PIL as a potential diagnosis should be considered even in the absence of any adolescent-illness history for adults with recurrent limb convulsions, low calcium and magnesium, hypoproteinemia, and high PTH levels. MCT diet, as a dietary supplement, can effectively improve the clinical symptoms of PIL patients while providing pharmacotherapy after the final diagnosis was made by a thorough detailed analysis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Choudhery MS, Pakistan; Panteris V, Greece S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Vardy PA, Lebenthal E, Shwachman H. Intestinal lymphagiectasia: a reappraisal. Pediatrics. 1975;55:842-851. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Waldmann TA, Steinfeld JL, Dutcher TF, Davidson JD, Gordon RS. The role of the gastrointestinal system in "idiopathic hypoproteinemia". Gastroenterology. 1961;41:197-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dong J, Xin J, Shen W, Wen T, Chen X, Sun Y, Wang R. CT Lymphangiography (CTL) in Primary Intestinal Lymphangiectasia (PIL): A Comparative Study with Intraoperative Enteroscopy (IOE). Acad Radiol. 2019;26:275-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bastepe M. The GNAS locus and pseudohypoparathyroidism. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;626:27-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wen J, Tang Q, Wu J, Wang Y, Cai W. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia: four case reports and a review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3466-3472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Steinfeld JL, Davidson JD, Gordon RS, Greene FE. The mechanism of hypoproteinemia in patients with regional enteritis and ulcerative colitis. Am J Med. 1960;29:405-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ungaro R, Babyatsky MW, Zhu H, Freed JS. Protein-losing enteropathy in ulcerative colitis. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012;6:177-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chieng JH, Garrett J, Ding SL, Sullivan M. Clinical presentation and endoscopic features of primary gastric Burkitt lymphoma in childhood, presenting as a protein-losing enteropathy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Petersen VP, Hastrup J. Protein-losing enteropathy in constrictive pericarditis. Acta Med Scand. 1963;173:401-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hourigan SK, Anders RA, Mitchell SE, Schwarz KB, Lau H, Karnsakul W. Chronic diarrhea, ascites, and protein-losing enteropathy in an infant with hepatic venous outflow obstruction after liver transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:E328-E331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Heresbach D, Raoul JL, Genetet N, Noret P, Siproudhis L, Ramée MP, Bretagne JF, Gosselin M. Immunological study in primary intestinal lymphangiectasia. Digestion. 1994;55:59-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fuss IJ, Strober W, Cuccherini BA, Pearlstein GR, Bossuyt X, Brown M, Fleisher TA, Horgan K. Intestinal lymphangiectasia, a disease characterized by selective loss of naive CD45RA+ lymphocytes into the gastrointestinal tract. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:4275-4285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Grant E, Junker A. Nine-year-old girl with lymphangiectasia and chest pain. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:659, 663-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Alfano V, Tritto G, Alfonsi L, Cella A, Pasanisi F, Contaldo F. Stable reversal of pathologic signs of primitive intestinal lymphangiectasia with a hypolipidic, MCT-enriched diet. Nutrition. 2000;16:303-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |