Published online Jun 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5441

Peer-review started: September 23, 2021

First decision: January 10, 2022

Revised: January 19, 2022

Accepted: April 21, 2022

Article in press: April 21, 2022

Published online: June 6, 2022

Processing time: 252 Days and 8.1 Hours

Multiple congenital anomalies-hypotonia-seizures syndrome 1 (MCAHS1) associated with mutations in PIGN gene.

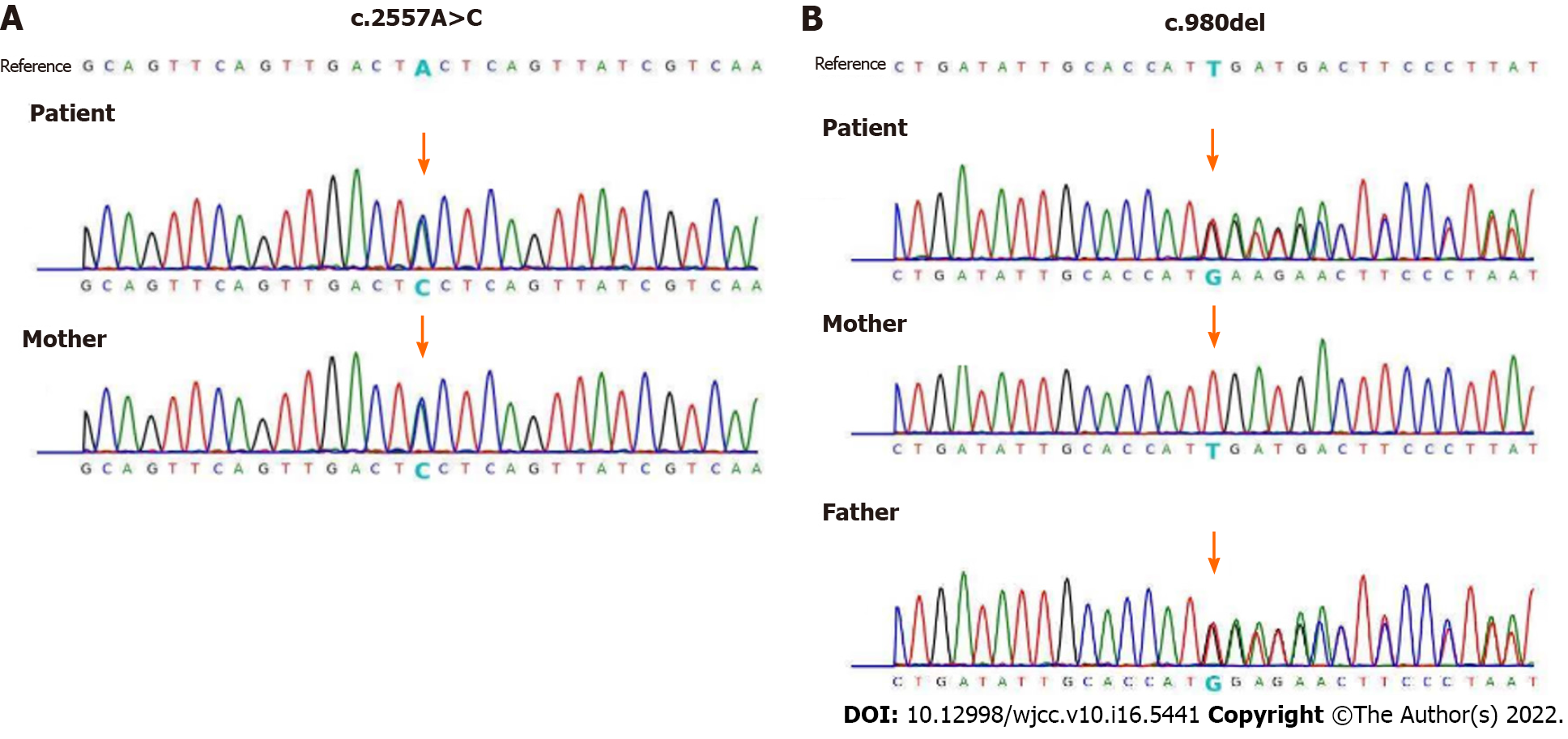

The authors report 1 case of a 16 years old girl who was presented with epilepsy, developmental delay and cerebellar atrophy. She harbors a compound heterozygous variant in the PIGN gene, include a nonsense splice site mutation (c.2557A>C) which was inherited from her mother, and a novel site mutation (c.980del) which was inherited from her father.

This case report expands the mutation spectrum found in PIGN gene, and strengthens the association between PIGN mutation and MCAHS1. Mutations in PIGN gene may be an underestimated cause of epilepsy. The authors recommend that, for patients with epilepsy or prenatal diagnosis of highly suspicious fetus, gene sequencing should be the preferred detection method.

Core Tip: We report 1 case of a 16-year-old girl who presented with epilepsy, developmental delay, and cerebellar atrophy. She harbors compound heterozygous variants in the PIGN gene, including a nonsense splice site mutation (c.2557A>C) that was inherited from her mother and a novel site mutation (c.980del) that was inherited from her father. The maternally inherited variant (c.2557A>C) has not been seen observed in the gnomAD and 1000genomes, which was called variants of unknown significance. The novel mutation c.980del (paternally inherited) that was detected in the prohand was predicted to be “probably damaging”.

- Citation: Hou F, Shan S, Jin H. PIGN mutation multiple congenital anomalies-hypotonia-seizures syndrome 1: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(16): 5441-5445

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i16/5441.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5441

Multiple congenital anomalies-hypotonia-seizures syndrome 1 (MCAHS1) associated with mutations in PIGN gene, is an autosomal recessive disease featured as epilepsy, stunting, hypotonica, and various congenital disorders. This was initially described in 2011[1]. Mutation in the PIGN gene involved in GPI-anchor pathway have been identified cause varied neurological abnormalities[1-4].The authors report on a 16 years old girl who was presented with epilepsy, developmental delay and cerebellar atrophy. She harbors a compound heterozygous variant in the PIGN gene, include a nonsense splice site mutation (c.2557A>C) which was inherited from her mother, and a novel site mutation (c.980del) which was inherited from her father.

A female, 16 years old, was presented with epilepsy, developmental delay and cerebellar atrophy.

Weakness of muscles was noticed at age 2 years old. At 1 year of age, she developed clinical seizures. Her seizure types include twitching movements, starting episodes, cluster seizures, and spasms. At a year and a half, there was only partial response to anti-convulsive therapy. Subsequently, global developmental delay was noted by 2 years old of age, there was no speech, and she needed assistance with daily life activities.

She was vigorous in the newborn period and passed her newborn disease screening, began walking around the age of 18 mo.

The patient was the second child of the family (non-consanguineous), her mother was 33 years old. She was born at full term with normal birth parameters, the pregnancy was normal, there was no known teratogenic exposure.

The parents does not have a personal history of seizures, nor is there a family history seizures.

Clinical examination documented the eyes were deep set with nystagmus, a small nose with nasalbridge (Figure 1).

Whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed commercially at Berrygenomics on the patient and her parents. Sequencing was performed on Illumina Novaseq 6000 (Illumina, San Diego, United States), using the Nano WES Human Exome V1.0 (Berrygenomics, Beijing, China) kit with 200 bp paired-end read, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Annotation of variants was performed using GATK (https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/), gnomAD (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/), 1000genomes (http://browser.1000genomes.org), SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org), FATHMM (http://fathmm.biocompute.org.uk), MutationAssessor (http://mutationassessor.org), OMIM (http://www.omim.org), ClinVar (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar), HGMD (http://www.hgmd.org).

Sequence analysis of exon 28 and 12 of PIGN, using genomic DNA from the patient and her parents were performed by amplification of a 438 bp and 239 bp fragment containing the putative mutation identified via exome sequencing. The sense primer sequence was 5’-TAAGTCAGTTTCATCACCGTTCTAT-3’ and the antisense primer sequence was 5’-ATTTCCTCTAATGACAAGCAACAC-3’ for exon 28. The sense primer sequence was 5’-TCTAGCAAATGACACTTTTAGAGA-3’, and the antisense primer sequence was 5’-TTCCTTACCACTGAGTTAAGAGG-3’ for exon 12.

Neuropsychological testing demonstrated moderate intellectual disability. Brain imaging showed the progression of mild global cerebral volume loss and cerebellar atrophy. The parents could not provide the results of previous test, including brain magnetic resonance imaging, various metabolic tests.

Whole Exome sequencing was performed commercially at BerryGenomics on the patient and her parents. Compound heterozygous mutations in PIGN gene were found, maternally inherited c.2557A>C and paternally inherited c.980del. The mutations were validated by sanger sequencing in the patient and her parents (Figure 2).

The authors also examined several small insertion/deletion variants (Indels), but none of these had an apparent connection to the clinical phenotype.

The present therapies for patients with PIGN gene associated illnesses are mainly supportive, which were aimed to reduce the development of epileptic seizures.

The authors will keep on to follow the patient’s disease development. This diagnosis allowed permitted appropriate genetic counseling with related risk evaluation.

There are more than 20 genes that participated in GPI-anchor biosynthesis pathway. PIGN is responsible for supplement of phosphoethanolamine to the primary mannose in GPI[2]. Mutations in the PIGN gene involved in GPI biosynthesis, have been identified associated with MCAHS1[1,5,6]. The authors report a patient with epilepsy, global delay, cerebellar atrophy with a PIGN mutation. The maternally inherited variant (c.2557A>C) has not been seen observed in the gnomAD and 1000genomes, which was called variants of unknown significance. The original mutation c.980del (paternally inherited) discovered in the prohand was estimated as “probably damaging”. The novel mutation changes the gene’s open reading frameshift, support the conclusion that the novel mutation detected in the patient cause major damage to the GPI-anchored protein, finally leading to the disorder.

Unlike previous reports[1,5,6], the patient did not have other visceral congenital anomalies of urinary, cardiac or gastrointestinal systems. Gastro-esophageal reflux, diaphragmatic hernia, brachycephaly, flat face, hypoplasia of distal parts of all fingers, open mouth, drooling have not been seen in the patient. Evaluation for mutations in PIGN causing PIGN associated epilepsy or MCAHS1 should be considered in patients of all ethnicities with epilepsy. These phenotypic differences may be explained as allele specific effects.

The clinical severity of the disease seems to correlate with the predicted functional severity of the mutations seen in PIGN[6]. Depending upon the severity of mutations, major congenial anomalies may also be present. Other hypotheses of environmental and genetic modification need to be considered. It should also be noted here that for PIGN gene-associated with disability, some tissues are more sensitive than others during body development.

This case report expands the mutation spectrum found in PIGN gene, and strengthens the association between PIGN mutation and MCAHS1. Mutations in PIGN gene may be an underestimated cause of epilepsy. The authors recommend that, for patients with epilepsy or prenatal diagnosis of highly suspicious fetus, gene sequencing should be the preferred detection method.

Authors are grateful to the patients and their families for their collaboration. The laboratory examination and data analysis were conducted in BerryGenomics.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Genetics and heredity

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Beran RG, India; Showkat HI, India S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Maydan G, Noyman I, Har-Zahav A, Neriah ZB, Pasmanik-Chor M, Yeheskel A, Albin-Kaplanski A, Maya I, Magal N, Birk E, Simon AJ, Halevy A, Rechavi G, Shohat M, Straussberg R, Basel-Vanagaite L. Multiple congenital anomalies-hypotonia-seizures syndrome is caused by a mutation in PIGN. J Med Genet. 2011;48:383-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Freeze HH, Eklund EA, Ng BG, Patterson MC. Neurology of inherited glycosylation disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:453-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Brady PD, Moerman P, De Catte L, Deprest J, Devriendt K, Vermeesch JR. Exome sequencing identifies a recessive PIGN splice site mutation as a cause of syndromic congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Eur J Med Genet. 2014;57:487-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ohba C, Okamoto N, Murakami Y, Suzuki Y, Tsurusaki Y, Nakashima M, Miyake N, Tanaka F, Kinoshita T, Matsumoto N, Saitsu H. PIGN mutations cause congenital anomalies, developmental delay, hypotonia, epilepsy, and progressive cerebellar atrophy. Neurogenetics. 2014;15:85-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Khayat M, Tilghman JM, Chervinsky I, Zalman L, Chakravarti A, Shalev SA. A PIGN mutation responsible for multiple congenital anomalies-hypotonia-seizures syndrome 1 (MCAHS1) in an Israeli-Arab family. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170A:176-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fleming L, Lemmon M, Beck N, Johnson M, Mu W, Murdock D, Bodurtha J, Hoover-Fong J, Cohn R, Bosemani T, Barañano K, Hamosh A. Genotype-phenotype correlation of congenital anomalies in multiple congenital anomalies hypotonia seizures syndrome (MCAHS1)/PIGN-related epilepsy. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170A:77-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |