Published online May 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i15.4886

Peer-review started: September 19, 2021

First decision: October 18, 2021

Revised: October 29, 2021

Accepted: April 3, 2022

Article in press: April 3, 2022

Published online: May 26, 2022

Processing time: 247 Days and 1.9 Hours

Nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours are difficult to diagnose in the early stage of disease due to a lack of clinical symptoms, but they can rarely manifest as autoimmune pancreatitis. Autoimmune pancreatitis is an uncommon disease that may cause recurrent acute pancreatitis and is therefore often regarded as a special type of chronic pancreatitis.

We report a case of a 42-year-old female who had nonspecific upper abdominal pain for 4 years and radiological abnormalities of the pancreas that mimicked autoimmune pancreatitis. The symptoms and pancreatic imaging did not improve following 1 year of steroid therapy. Finally, pancreatic biopsy was performed through endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy, and nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours were ultimately diagnosed. Pancreatectomy has resolved her symptoms.

Therefore, the differentiation of nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours from autoimmune pancreatitis is very important, although it is rare. We propose that endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy should be performed if imaging characteristics are equivocal or the diagnosis is in question.

Core Tip: We report a case of a 42-year-old female patient who suffered from nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours but was misdiagnosed for 4 years. After the 3-year follow-up, she was misdiagnosed with autoimmune pancreatitis through radiography and underwent 1 year of corticosteroid therapy. However, her symptoms worsened. Biopsy via endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy made a correct diagnosis of nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours, and pancreatectomy resolved the symptoms. Therefore, we propose that endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy should be performed if imaging characteristics are equivocal or the diagnosis is in question.

- Citation: Lin ZQ, Li X, Yang Y, Wang Y, Zhang XY, Zhang XX, Guo J. Nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours misdiagnosed as autoimmune pancreatitis: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(15): 4886-4894

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i15/4886.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i15.4886

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (PNETs) are uncommon and account for 1%-2% of all pancreatic neoplasms[1], with annual worldwide incidences of approximately 3.2 cases per million in 2003 and 8 cases per million in 2012[2]. PNETs are composed of both functional and nonfunctional PNETs. Functioning PNETs are often characterized by symptoms caused by hormone secretion, such as hypoglycaemia, multiple peptic ulcers, and diarrhoea, which enable early diagnosis. Nonfunctional PNETs are difficult to diagnose in the early stage due to a lack of typical clinical symptoms. Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is also a rare disease that may cause recurrent acute pancreatitis and is recognized as a special type of chronic pancreatitis[3]. Although many guidelines and management strategies for AIP have been developed and published in recent years, it is clinically difficult to differentiate between AIP and pancreatic cancer, especially with diffusely enlarged pancreatic tumours. Here, we report a case of pancreatic endocrine neoplasm that was misdiagnosed as AIP for many years.

A 42-year-old female suffered from nonspecific upper abdominal pain for 4 years, without fever or weight loss. The patient’s symptoms had worsened for 1 year.

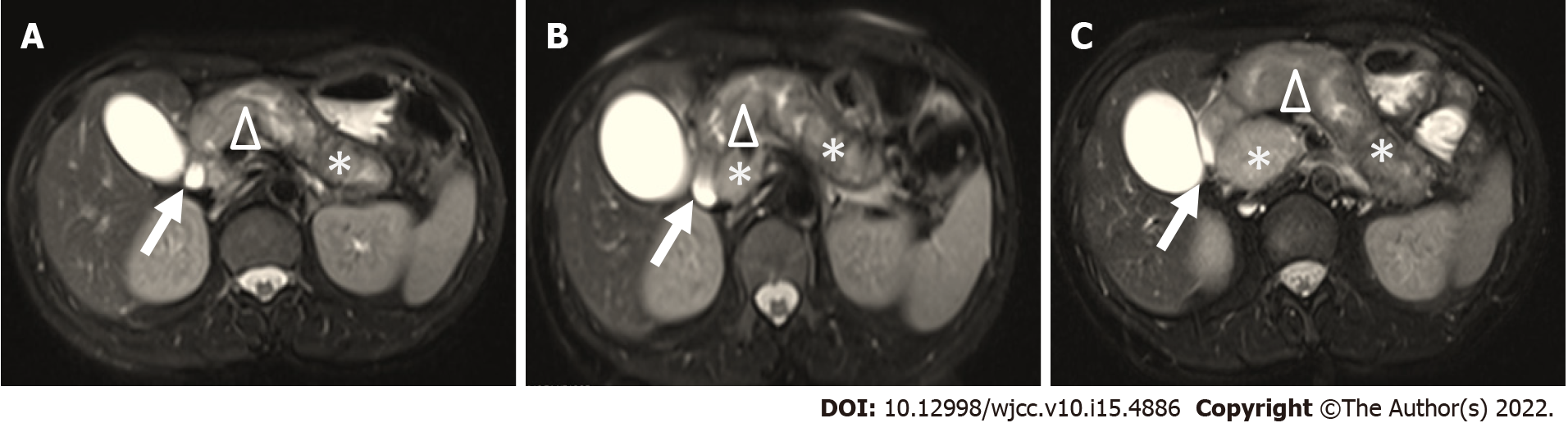

When the patient first suffered from upper abdominal pain, she was diagnosed with chronic gastritis and treated with stomach-protective drugs for 6 mo, with no significant relief. Due to her nonspecific upper abdominal pain, the patient underwent abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) every year from 2015 to 2017. MRI demonstrated diffuse pancreatic enlargement, expansion of the main pancreatic duct, enhancement of the parenchyma, no obvious mass and clear peripancreatic fat space. No obvious abnormalities were found in the liver, gallbladder, spleen or kidneys (Figure 1A-C). She was then diagnosed with chronic pancreatitis and received pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy, which did improve her symptoms. Since then, her symptoms appeared recurrently and were relieved with oral enzyme supplementation. One year ago, her abdominal pain was aggravated, and she experienced jaundice, at which time she was diagnosed with “autoimmune pancreatitis” at a local hospital. After taking methylprednisolone tablets and ursodeoxycholic acid, her condition was slightly improved and maintained with methylprednisolone 16 mg/d for 1 year until she was admitted to our hospital when her symptoms worsened.

The patient was a healthy person without diabetes, hypertension or other underlying diseases.

The patient had no family history.

Physical examination showed slight abdominal tenderness, no rebound tenderness and no tension.

For further diagnosis and treatment, we performed a series of laboratory and imaging examinations. Liver function tests, such as serum alanine aminotransferase and aspartate transaminase, were slightly above normal limits (alanine aminotransferase, 100 IU/L and aspartate transaminase, 89 IU/L). However, amylase and lipase were within normal limits. The serum immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) level was normal at 0.217 g/L (0.035-1.500 g/L), and the antinuclear antibody spectrum was negative. Serum tumour markers, including carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), were high, at 4.21 ng/mL (normal < 3.4 ng/mL) and 153.2 U/mL (normal < 22 U/mL), respectively. Retrospective analysis of the results of laboratory tests of the patient from 2016 to 2018 found that alanine aminotransferase and aspartate transaminase were slightly higher than normal, fluctuating at approximately 100-150 IU/L and 70-100 IU/L, respectively. Her CA19-9 was becoming increasingly elevated (from 38.20 to 153.2 U/mL). IgG4 was negative from 2016 to 2018. The patient’s fasting blood sugar levels were normal.

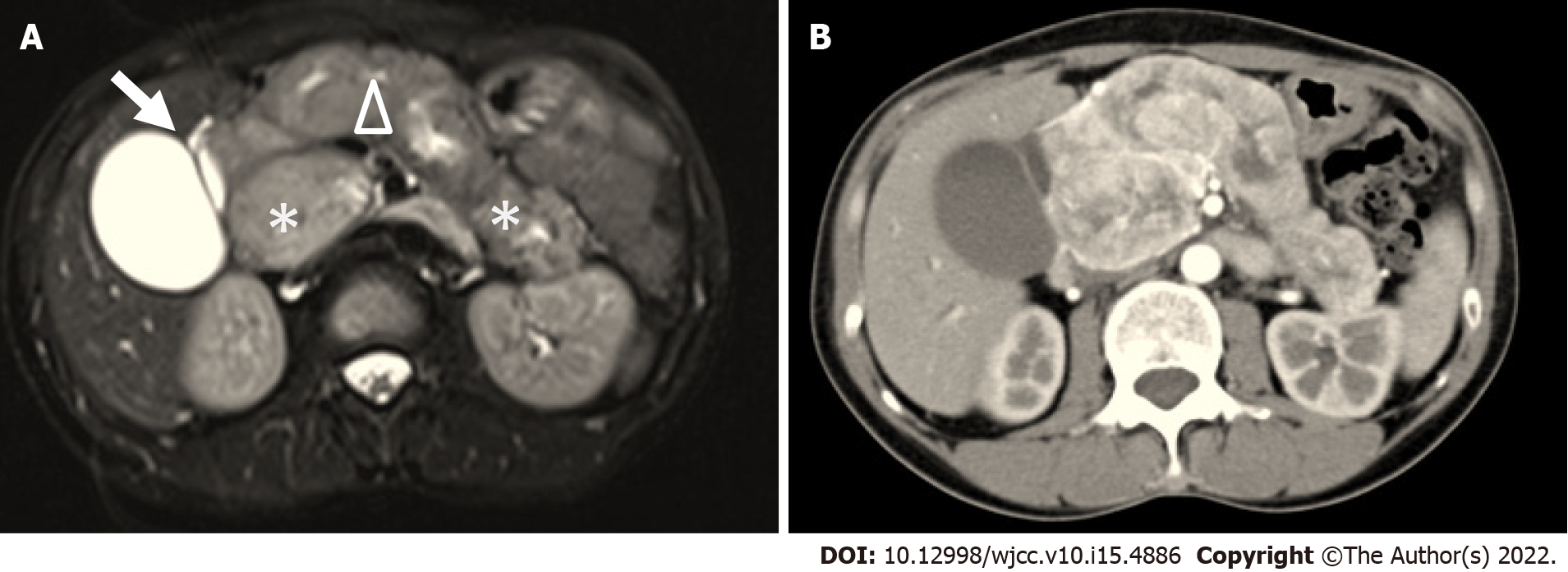

MRI (Figure 2A) at this admission showed a lesion at the head of the pancreas with sausage-like diffuse enlargement; gallbladder and common bile duct enlargement (common bile duct diameter: 2.0 cm) were also present. Suspicious lymph nodes and additional liver metastasis were not found. Compared with previous images, pancreatic enlargement progressed. Enlarged gallbladder without lithiasis or thick wall and dilation of the main pancreatic duct due to an oval mass located in the head of the pancreas, which was well defined. Abdominal multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) also revealed similar findings to MRI, and no substantial space occupying lesion was found (Figure 2B). Although imaging showed diffuse enlargement of the pancreas, the head of the pancreas was predominant and heterogeneous. The patient had dull upper abdominal pain with jaundice only once and never suffered from acute pancreatitis. After 1 year of steroid therapy, pancreatic enlargement showed no change, and CA19-9 increased every year. We doubted the original AIP diagnosis and considered the possibility of a pancreatic tumour. Then we performed abdominal endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). It confirmed the diffuse enlargement of the pancreas. However, the nature of the enlargement remains unknown. EUS-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy (EUS-FNA/FNB) was performed from the pancreas head.

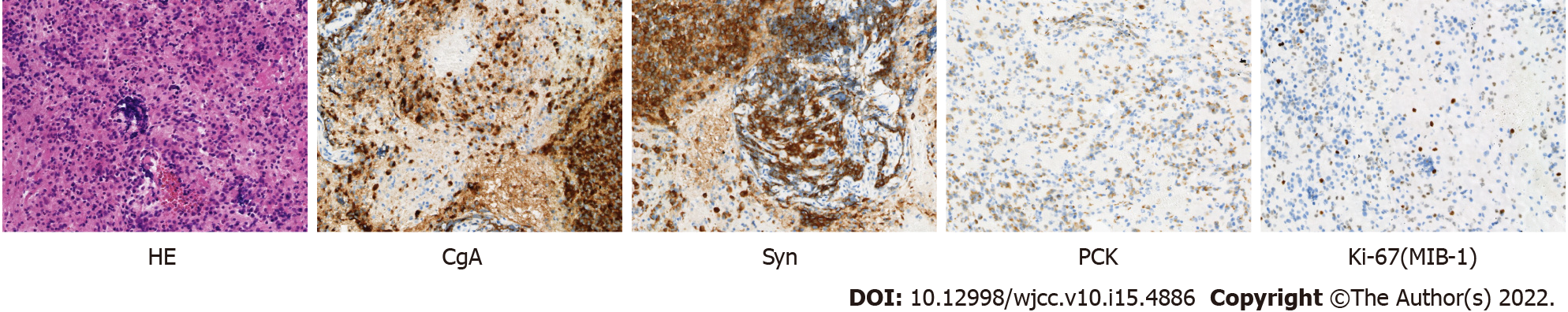

The pathological examination showed tumour cells. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of EUS-FNA/FNB demonstrated chromogranin A (CgA) (+), synaptophysin (+), pan-cytokeratin (+), Ki-67 (MIB-1) (approximately 10%+), somatostatin (-), gastrin (-), insulin (-), glucagon (-) and IgG4 (-) (Figure 3). According to the World Health Organization classification[4], pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour was diagnosed.

Methylprednisolone treatment was stopped for 1 mo, and pancreatectomy was arranged. Before pancreatectomy, computed tomography angiography was undertaken to establish whether the lesion had invaded the vascular structures. The computed tomography angiography showed tumour lesions in the head of the pancreas. The gallbladder was still enlarged, and the maximum diameter of the common bile duct reached 3.4 cm with the upper segment compressed and narrowed. The porta hepatis and intrahepatic bile ducts were all significantly dilated. The main portal vein was slightly dilated with a diameter of approximately 2.0 cm. There was local compression of the portal vein, and the splenic vein and right renal artery and vein were all narrowed, accompanied by multiple tortuous blood vessels shadowed around the stomach and spleen portal area.

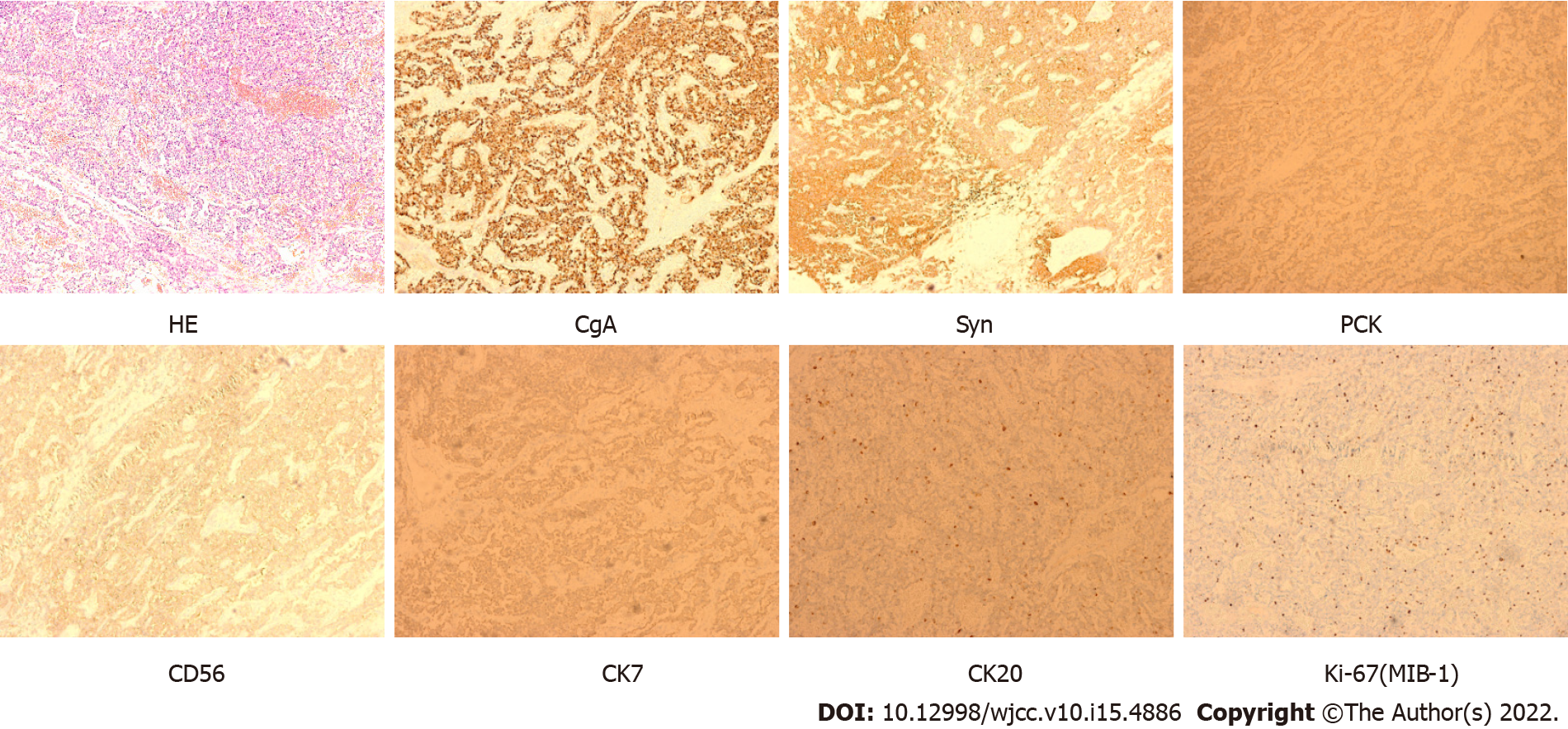

The patient finally underwent total pancreatectomy on 28 November 2018, and no hepatic metastasis was found. IHC showed CgA (+), synaptophysin (+), pan-cytokeratin (+), CD56 (+), CK7 (+), CK20 (+), Ki-67 (MIB-1) (+, 3%-7%), epithelial membrane antigen (-), CD10 (-), D2-40 (-), inhibin (-), somatostatin (-), gastrin (-), insulin (-) and glucagon (-) (Figure 4), which is compatible with a neuroendocrine tumour (Grade 2) according to the World Health Organization classification[4]. Combined with the patient’s symptoms, these findings support the diagnosis of nonfunctional PNET.

The patient recovered well after the operation and required long-term oral pancreatin enteric-coated capsules.

Here, we first report a case of nonfunctional PNET misdiagnosed as AIP for many years. Most previous studies showed that AIP mimicked neuroendocrine tumours or pancreatic cancer[5,]. To avoid misdiagnosis and delay the timing of the operation, differentiation of nonfunctional PNETs from AIP is very important, although it is rare. The clinician should attach importance to this evaluation.

Nonfunctional PNETs are defined by the absence of hormone hypersecretion syndrome[1,7]. Some recent studies have indicated that approximately 60%-90% of PNETs are nonfunctional and are generally diagnosed at late stages due to the lack of typical clinical symptoms[8,9]. A multicentre observational study showed that 32% of nonfunctional PNETs had liver metastases at first diagnosis[10], and other studies showed that 60% presented distant metastases and usually hepatic metastases[11]. The 5-year survival rate of nonfunctional PNETs is 43%, and the median overall survival of nonfunctional PNETs is 38%[7]. Hepatic metastasis is a major predictor of poor survival[12]. If symptoms appear, the common symptoms are abdominal pain (35%-78%), weight loss (20%-35%) and anorexia and nausea (45%), while intra-abdominal bleeding (4%-20%), jaundice (17%-50%) or palpable masses are less common (7%-40%)[13-15]. The positivity of synaptophysin and CgA by IHC indicates neuroendocrine origin[7]. Based on proliferation assessed by mitotic count and Ki-67 index from the 2018 World Health Organization classification, PNETs were divided into three tiers (G1, G2 and G3)[4], and this patient was G2.

AIP is a special form of chronic pancreatitis and has a low incidence[3]. Recently one study showed AIP has an annual incidence rate of 3.1 per 100000 persons in Japan[16]. The clinical manifestation of AIP is not severe abdominal pain, but it is often seen in acute pancreatitis or acute exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis. Some AIP patients suffer only mild or almost no abdominal pain[17,18]. Approximately 33%-59% of AIP patients have obstructive jaundice, 15% of them have back pain or weight loss, and 15% of patients have no symptoms[19]. Therefore, it is difficult to distinguish AIP from nonfunctional PNET in terms of symptoms. The whole course of this case we presented here was manifested only by atypical abdominal pain and one occurrence of jaundice, without weight loss or onset of acute pancreatitis. All of these factors make diagnosis difficult.

Recently, the development of high-quality imaging techniques has led to increased incidental diagnoses of nonfunctional PNETs[20,21]. MDCT usually shows circumscribed hypervascular solid masses that rarely obstruct the pancreatic duct. Smaller lesions are usually homogeneous, and larger lesions are more likely to have heterogeneous enhancement[7]. Diffusion-weighted imaging MRI may be more sensitive than MDCT for detecting smaller lesions and liver metastases, which often show lower signal intensity than normal pancreatic tissue in fat-suppressed T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images[7,22,23]. Abdominal characteristic MDCT images of AIP normally show diffuse enlargement of the pancreas, referred to as sausage-shaped, with delayed enhancement and with a band-like structure that appears to surround all or part of the lesions, termed a “capsule-like rim”[24], which may be present in only approximately 30%-40% of AIP patients[25]. MRI for AIP includes diffuse hypointensity on T1-weighted images and slight hyperintensity on T2-weighted images[3]. Compared with MDCT scans, MRI provides better tissue contrast and plays an important role in the diagnosis of AIP[26].

It is difficult to distinguish nonfunctional PNETs from AIP due to the lack of typical imaging changes and liver metastasis, especially large diffuse swelling in this case. MDCT showed only a diffusely enlarged pancreas, especially in the head of the pancreas, and no typical “capsule-like rim.” MRI of the patient in 2015 showed a diffusely enlarged pancreas, and it seemed to have a ‘‘capsule-like rim’’ of a peripancreatic lesion, though not a typical one. Swollen pancreas showed a higher signal than the liver in T2-weighted images (Figure 1A). There were no significant changes during 2016 and 2017, and misdiagnosis based on conventional pancreatic imaging seems unavoidable.

Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy is a whole-body functional imaging method with 111indium isotope-labelled pentetreotide and shows significantly higher sensitivity than CT/MRI[27]. Recently, newer functional imaging studies utilizing positron emission tomography with 68Ga and 18F-DOPA have shown promising results that may be superior to conventional somatostatin receptor scintigraphy[28,29]. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumour Society Consensus recommends that somatostatin receptor-positron emission tomography imaging should replace 111indium-pentetreotide scanning[1] for identifying primary tumours and the extent of metastatic disease. However, these functional imaging techniques were not applied to this case.

CgA is a commonly used biomarker present in both tumours and blood for diagnosis in a fraction of nonfunctional PNETs and when evaluating response to therapy[30]. CgA is a glycoprotein, similar to secretory granulosin, present in secretory granules that store peptide hormones and catecholamines throughout the neuroendocrine system. However, CgA is also elevated in chronic renal or liver failure or patients treated with proton-pump inhibitors[28,31]. Another controversial biomarker is pancreatic polypeptide, which may be useful for the early detection of pancreatic tumours in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1[7]. However, CgA and pancreatic polypeptide were not tested in this patient. IgG4, a biomarker for type 1 AIP[3], was tested, but the levels were not high in this patient. In contrast, the serum CA19-9 level continued to increase in this case and is an important tumour biomarker for the early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer[32,33]. The progressive increases in these tumour markers may prompt physicians to highly suspect the possibility of pancreatic tumours, but further investigation is required.

In fact, ultrasound (US) is a first-line examination for abdominal discomfort. However, the operator-sensitive modality is highly subjective, leading to wide variation regarding sensitivity and specificity. Only a mean of 39% (range 17%–79%) of PNETs were detected[34]. The recent new technology of contrast-enhanced US, which can allow continuous evaluation of tumour enhancement patterns in the arterial, venous, and late phases, has led to improvement in the diagnostic capabilities, especially in the detection of liver metastases[34,35]. EUS can obtain the histological characteristics of gastrointestinal hierarchical structure and ultrasound images of the surrounding organs and is recognized as one of the most important preoperative procedures in the evaluation and management of PNETs[36,37]. First, EUS can detect lesions smaller than 2 cm to 3 cm in diameter, which are not often detected by CT[38]. In many systematic reviews, EUS identified PNETs in over 90% of cases[34,39]. More importantly, tissue specimens can be obtained by FNA through EUS. For this case, the patient was in a long-term outpatient follow-up in another department of our hospital, and MRI was performed every year since 2015. To have a better comparison, we considered MRI review. Therefore, the patient did not undergo a basal US examination first.

For lesions in the biliopancreatic region suggested by imaging, multidirectional and comprehensive analysis combined with an evaluation of clinical symptoms is needed. We should not ignore the suggestive role of imaging. Without any clinical symptoms, pancreatic enlargement is often found by imaging physical examination, such as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm[40]. One study showed the case of a patient with nonfunctioning well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the head of the pancreas associated with extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma by MRI and confirmed by surgery[41]. In this case, EUS was ultimately selected according to the imaging changes of MRI over the years.

The pancreatic tissue was obtained by EUS-FNA/FNB, and nonfunctional PNETs were ultimately confirmed by IHC in this case. EUS-FNA/FNB is a safe, less traumatic and more valuable technique for the detection, localization and diagnosis of identified lesions by imaging. EUS-FNA/FNB not only has higher sensitivity for PNETs but also detects lesions ranging from 4 cm to 10 cm[34,42] and provides additional information (e.g., distance from the main pancreatic duct and the Ki-67 proliferation index) for proper therapeutic management[43].

In summary, we report a nonfunctional PNET misdiagnosed as AIP. If imaging characteristics are equivocal or if the diagnosis is in question, EUS-FNA/FNB should be performed as soon as possible to confirm the diagnosis and to avoid delaying treatment.

Thanks to all medical staff in the clinical care of this patient. Thanks also to Professor Wang GZ and Dr. Abrams S from Liverpool University for their critical reading and correction.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Health care sciences and services

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Corvino A, Italy; Nyamuryekung’e M, Tanzania S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Howe JR, Merchant NB, Conrad C, Keutgen XM, Hallet J, Drebin JA, Minter RM, Lairmore TC, Tseng JF, Zeh HJ, Libutti SK, Singh G, Lee JE, Hope TA, Kim MK, Menda Y, Halfdanarson TR, Chan JA, Pommier RF. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society Consensus Paper on the Surgical Management of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Pancreas. 2020;49:1-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 52.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, Zhao B, Zhou S, Xu Y, Shih T, Yao JC. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1335-1342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1510] [Cited by in RCA: 2484] [Article Influence: 310.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 3. | Nagpal SJS, Sharma A, Chari ST. Autoimmune Pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:1301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rindi G, Klimstra DS, Abedi-Ardekani B, Asa SL, Bosman FT, Brambilla E, Busam KJ, de Krijger RR, Dietel M, El-Naggar AK, Fernandez-Cuesta L, Klöppel G, McCluggage WG, Moch H, Ohgaki H, Rakha EA, Reed NS, Rous BA, Sasano H, Scarpa A, Scoazec JY, Travis WD, Tallini G, Trouillas J, van Krieken JH, Cree IA. A common classification framework for neuroendocrine neoplasms: an International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and World Health Organization (WHO) expert consensus proposal. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:1770-1786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 546] [Cited by in RCA: 712] [Article Influence: 101.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Onda S, Okamoto T, Kanehira M, Fujioka S, Harada T, Hano H, Fukunaga M, Yanaga K. Histopathologically proven autoimmune pancreatitis mimicking neuroendocrine tumor or pancreatic cancer. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012;6:40-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tanaka Y, Takikawa T, Kume K, Kikuta K, Hamada S, Miura S, Yoshida N, Hongo S, Matsumoto R, Sano T, Ikeda M, Unno M, Masamune A. IgG4-related Diaphragmatic Inflammatory Pseudotumor. Intern Med. 2021;60:2067-2074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Falconi M, Bartsch DK, Eriksson B, Klöppel G, Lopes JM, O'Connor JM, Salazar R, Taal BG, Vullierme MP, O'Toole D; Barcelona Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system: well-differentiated pancreatic non-functioning tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:120-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 358] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Halfdanarson TR, Rabe KG, Rubin J, Petersen GM. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs): incidence, prognosis and recent trend toward improved survival. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1727-1733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 663] [Cited by in RCA: 621] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee LC, Grant CS, Salomao DR, Fletcher JG, Takahashi N, Fidler JL, Levy MJ, Huebner M. Small, nonfunctioning, asymptomatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs): role for nonoperative management. Surgery. 2012;152:965-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zerbi A, Falconi M, Rindi G, Delle Fave G, Tomassetti P, Pasquali C, Capitanio V, Boninsegna L, Di Carlo V; AISP-Network Study Group. Clinicopathological features of pancreatic endocrine tumors: a prospective multicenter study in Italy of 297 sporadic cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1421-1429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shin WY, Lee KY, Ahn SI, Park SY, Park KM. Cutaneous metastasis as an initial presentation of a non-functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9822-9826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mignon M. Natural history of neuroendocrine enteropancreatic tumors. Digestion. 2000;62 Suppl 1:51-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Matthews BD, Heniford BT, Reardon PR, Brunicardi FC, Greene FL. Surgical experience with nonfunctioning neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas. Am Surg. 2000;66:1116-1122. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Madura JA, Cummings OW, Wiebke EA, Broadie TA, Goulet RL Jr, Howard TJ. Nonfunctioning islet cell tumors of the pancreas: a difficult diagnosis but one worth the effort. Am Surg. 1997;63:573-577. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Cheslyn-Curtis S, Sitaram V, Williamson RC. Management of non-functioning neuroendocrine tumours of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 1993;80:625-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Masamune A, Kikuta K, Hamada S, Tsuji I, Takeyama Y, Shimosegawa T, Okazaki K; Collaborators. Nationwide epidemiological survey of autoimmune pancreatitis in Japan in 2016. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:462-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kamisawa T, Okamoto A, Funata N. Clinicopathological features of autoimmune pancreatitis in relation to elevation of serum IgG4. Pancreas. 2005;31:28-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kamisawa T, Wakabayashi T, Sawabu N. Autoimmune pancreatitis in young patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:847-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Okazaki K, Kawa S, Kamisawa T, Shimosegawa T, Tanaka M; Research Committee for Intractable Pancreatic Disease and Japan Pancreas Society. Japanese consensus guidelines for management of autoimmune pancreatitis: I. Concept and diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:249-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lee DW, Kim MK, Kim HG. Diagnosis of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Clin Endosc. 2017;50:537-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wu J, Sun C, Li E, Wang J, He X, Yuan R, Yi C, Liao W, Wu L. Non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: emerging trends in incidence and mortality. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dromain C, de Baere T, Lumbroso J, Caillet H, Laplanche A, Boige V, Ducreux M, Duvillard P, Elias D, Schlumberger M, Sigal R, Baudin E. Detection of liver metastases from endocrine tumors: a prospective comparison of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:70-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lee L, Ito T, Jensen RT. Imaging of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: recent advances, current status, and controversies. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18:837-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Irie H, Honda H, Baba S, Kuroiwa T, Yoshimitsu K, Tajima T, Jimi M, Sumii T, Masuda K. Autoimmune pancreatitis: CT and MR characteristics. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:1323-1327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Takahashi N, Fletcher JG, Hough DM, Fidler JL, Kawashima A, Mandrekar JN, Chari ST. Autoimmune pancreatitis: differentiation from pancreatic carcinoma and normal pancreas on the basis of enhancement characteristics at dual-phase CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:479-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Takahashi M, Fujinaga Y, Notohara K, Koyama T, Inoue D, Irie H, Gabata T, Kadoya M, Kawa S, Okazaki K; Working Group Members of The Research Program on Intractable Diseases from the Ministry of Labor, Welfare of Japan. Diagnostic imaging guide for autoimmune pancreatitis. Jpn J Radiol. 2020;38:591-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Schillaci O, Spanu A, Scopinaro F, Falchi A, Corleto V, Danieli R, Marongiu P, Pisu N, Madeddu G, Delle Fave G. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy with 111In-pentetreotide in non-functioning gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Int J Oncol. 2003;23:1687-1695. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Cloyd JM, Poultsides GA. Non-functional neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas: Advances in diagnosis and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9512-9525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Koopmans KP, de Vries EG, Kema IP, Elsinga PH, Neels OC, Sluiter WJ, van der Horst-Schrivers AN, Jager PL. Staging of carcinoid tumours with 18F-DOPA PET: a prospective, diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:728-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Falconi M, Eriksson B, Kaltsas G, Bartsch DK, Capdevila J, Caplin M, Kos-Kudla B, Kwekkeboom D, Rindi G, Klöppel G, Reed N, Kianmanesh R, Jensen RT; Vienna Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for the Management of Patients with Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Non-Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103:153-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1097] [Cited by in RCA: 985] [Article Influence: 109.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Giusti M, Sidoti M, Augeri C, Rabitti C, Minuto F. Effect of short-term treatment with low dosages of the proton-pump inhibitor omeprazole on serum chromogranin A levels in man. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;150:299-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wang Z, Tian YP. Clinical value of serum tumor markers CA19-9, CA125 and CA72-4 in the diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2:265-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Chen Y, Gao SG, Chen JM, Wang GP, Wang ZF, Zhou B, Jin CH, Yang YT, Feng XS. Serum CA242, CA199, CA125, CEA, and TSGF are Biomarkers for the Efficacy and Prognosis of Cryoablation in Pancreatic Cancer Patients. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2015;71:1287-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sundin A, Vullierme MP, Kaltsas G, Plöckinger U; Mallorca Consensus Conference participants; European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumors: radiological examinations. Neuroendocrinology. 2009;90:167-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hoeffel C, Job L, Ladam-Marcus V, Vitry F, Cadiot G, Marcus C. Detection of hepatic metastases from carcinoid tumor: prospective evaluation of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2040-2046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Jensen RT, Cadiot G, Brandi ML, de Herder WW, Kaltsas G, Komminoth P, Scoazec JY, Salazar R, Sauvanet A, Kianmanesh R; Barcelona Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms: functional pancreatic endocrine tumor syndromes. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:98-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 465] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Rösch T, Lightdale CJ, Botet JF, Boyce GA, Sivak MV Jr, Yasuda K, Heyder N, Palazzo L, Dancygier H, Schusdziarra V. Localization of pancreatic endocrine tumors by endoscopic ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1721-1726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Khashab MA, Yong E, Lennon AM, Shin EJ, Amateau S, Hruban RH, Olino K, Giday S, Fishman EK, Wolfgang CL, Edil BH, Makary M, Canto MI. EUS is still superior to multidetector computerized tomography for detection of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:691-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | James PD, Tsolakis AV, Zhang M, Belletrutti PJ, Mohamed R, Roberts DJ, Heitman SJ. Incremental benefit of preoperative EUS for the detection of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:848-56.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Qin Y, Zhong W, Ma Y, Wang L, Peng C. Glucagonoma with diffuse enlargement of pancreas mimicking autoimmune pancreatitis diagnosed by EUS-guided FNA. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94:862-863.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Maurea S, Corvino A, Imbriaco M, Avitabile G, Mainenti P, Camera L, Galizia G, Salvatore M. Simultaneous non-functioning neuroendocrine carcinoma of the pancreas and extra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma. A case of early diagnosis and favorable post-surgical outcome. JOP. 2011;12:255-258. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Zilli A, Arcidiacono PG, Conte D, Massironi S. Clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasonography on the management of neuroendocrine tumors: lights and shadows. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:6-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Melita G, Pallio S, Tortora A, Crinò SF, Macrì A, Dionigi G. Diagnostic and Interventional Role of Endoscopic Ultrasonography for the Management of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. J Clin Med. 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |