Published online May 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i15.4856

Peer-review started: May 31, 2021

First decision: June 25, 2021

Revised: July 14, 2021

Accepted: April 2, 2022

Article in press: April 2, 2022

Published online: May 26, 2022

Processing time: 358 Days and 8.1 Hours

Functional constipation (FC) is a common and chronic gastrointestinal disease and its treatment remains challenging.

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) on efficacy rate, global symptoms, bowel movements and the Bristol Stool Scale score in patients with FC by summarizing current available randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

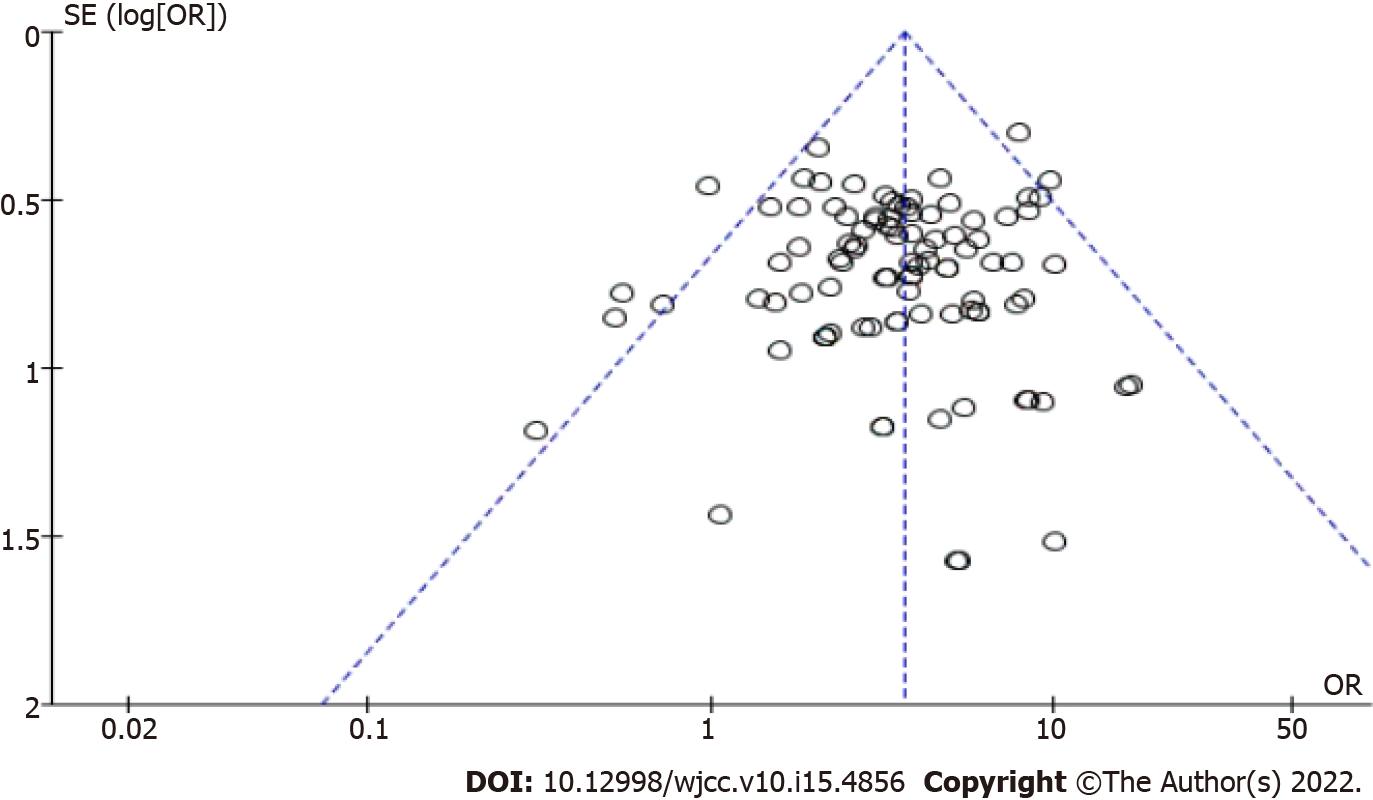

RCTs with CHM to treat FC were identified by a systematic search of six databases from inception to October 20, 2020. Two independent reviewers assessed the quality of the included articles and extracted data. Meta-analyses were performed to odds ratio (OR), mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) using random-effects models. Subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses were used to explore and interpret the sources of heterogeneity. The funnel plot, Begg’s test and Egger’s test were used to detect publication bias.

Ninety-seven studies involving 8693 patients were included in this work. CHM was significantly associated with a higher efficacy rate (OR: 3.62, 95%CI: 3.19-4.11, P < 0.00001) less severe global symptoms (OR: 4.03, 95%CI: 3.49-4.65, P < 0.00001) compared with control treatment, with the low heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.76). CHM was also associated with more frequent bowel movements (MD 0.83, 95%CI: 0.67-0.98, P < 0.00001), a lower score on the Bristol Stool Scale (OR: 1.63, 95%CI: 1.15-2.32, P < 0.006), and a not significant recurrence rate (OR: 0.47, 95%CI: 0.22-0.99, P = 0.05). No serious adverse effects of CHM were reported.

In this meta-analysis, we found that CHM may have potential benefits in increasing the number of bowel movements, improving stool characteristics and alleviating global symptoms in FC patients. However, a firm conclusion could not be reached because of the poor quality of the included trials. Further trials with higher quality are required.

Core Tip: In this meta-analysis, we found that Chinese herbal medicine may have potential benefits in increasing the number of bowel movements, improving stool characteristics and alleviating global symptoms in functional constipation patients. However, a firm conclusion could not be reached because of the poor quality of the included trials. Further trials with higher quality are required.

- Citation: Lyu Z, Fan Y, Bai Y, Liu T, Zhong LL, Liang HF. Outcome of the efficacy of Chinese herbal medicine for functional constipation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(15): 4856-4877

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i15/4856.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i15.4856

Functional constipation (FC) is a common and chronic gastrointestinal disease. It has a prevalence of 14% in the population in Asia[1] and 15.6% of the population in Hong Kong[2], representing a huge care burden. It is estimated that about 3.2 million FC patients in the United States visited medical centers in 2012 and the direct cost per patient for chronic constipation ranged from $1912 to $7522 per year[3]. In addition, functional constipation greatly affects the quality of life of patients creating an important mental and physical burden[4].

The treatment of functional constipation remains challenging. Osmotic laxatives, irritant laxatives and stool softeners are commonly used to treat FC[5]. However, up to 47% of patients were not completely satisfied with such treatment mainly due to concerns about treatment efficacy, safety, adverse reactions and cost[6]. Therefore, patients with FC usually take a self-management approach and try to seek complementary and alternative therapy and Chinese herbal medicine is their usual choice.

Through a randomized controlled trial (RCT), McRorie et al[7] found that Psyllium, an herb, was superior to docusate sodium, a laxative, for the treatment of chronic constipation. Two systematic reviews reported that Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) was effective in treating constipation[8-9]. But they were not clear whether herbs improve bowel movement, increase the frequency of voluntary defecation or alleviate symptoms of constipation. Some people even have concerns about the safety of Chinese herbs. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of CHM on efficacy rate, global symptoms, bowel movements and the Bristol Stool Scale score in patients with FC by summarizing current available RCTs.

This systematic review was conducted following the guideline of Preferred reporting items for systematic review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement[10].

Studies meeting the following criteria will be included: (1) Participants: patients met established diagnostic criteria of FC, including Rome I, II, III, IV criteria, without restrictions for age, sex, ethnicity or setting type; (2) Type of studies: only randomized controlled trials were eligible; (3) Type of intervention: studies compared any CHM with Western medicine (WM) or placebo. For studies using other agents as the third arm, only the two arms using CHM would be included for analysis; and (4) Type of outcome measurements: the efficacy rate (ER); the frequency of bowel movement (BM); the assessments of the global symptom (GS); the score of the Bristol Stool Scale (BSS); the recurrence rate (RR) within follow-up, and reported adverse effects (AEs).

Trials were excluded: (1) Did not meet the criteria above; (2) Involved animal studies or in vitro studies; (3) Case series or reviews and conference abstracts; (4) Valid original data were unable to obtain even when contacting the author; and (5) Similar studies were reported without additional data to analyze and extract.

MEDLINE, Embase, SinoMed, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang Database and China Science and Technology Journal Database (VIP) were searched. An electronic search of the databases was performed from 1994, the year of the establishment of Rome criteria, up to June 2020, using the following search terms: (functional constipation) AND (Chinese herbal medicine OR Chinese traditional medicine OR Oriental medicine OR complementary medicine). We also hand-searched conference abstracts. Reference lists of all retrieved articles and reviews were screened as well. We limited the literature search to RCTs on human subjects. No language restrictions were used. Search strategies used for the Medline database were as Supplementary material 1. Two reviewers (Lyu Z and Bai Y) independently read the title and abstract to initially select the studies that meet the eligibility criteria. Further reading of the full text was used to determine the included studies. If the reviewers had different opinions, the third researcher (Zhong LL) made the final decision.

Two reviewers (Lyu Z and Bai Y) independently extracted data on participant characteristics from the selected studies in a standardized data extraction form. We extracted the following information from each included article: first author, year of publication, publication language, number of participants, participant characteristics, duration of intervention and follow-up period, number of dropouts, controlled intervention and outcome data. Authors of trials were contacted for missing data and additional information. Any disparities between the two reviewers were discussed and resolved by consensus.

The ER was considered a primary outcome. The frequency of BM, the assessments of the GS, the score of the BSS, the RR within follow-up and reported AEs were considered to be secondary outcomes.

ER: To access the efficacy of CHM on the number of participants with any self-assessed relief of constipation symptoms.

BM: To determine the efficacy of CHM on the frequency of BM per week, e.g., 4 times/week.

GS: To assess the efficacy of CHM on the number of participants with any self-assessed relief of global symptoms (including symptoms other than constipation).

BSS: To assess the efficacy of CHM on the number of participants with normal stool evaluated by Bristol Stool Scale ("soft sausage shape, soft lumps, muddy and watery stools" as normal stools).

RR: Recurrence means aggravation of constipation symptoms or reduction of BM to an untreated condition or less within the period of followed-up.

AEs: Including adverse events and clinical laboratory evaluations.

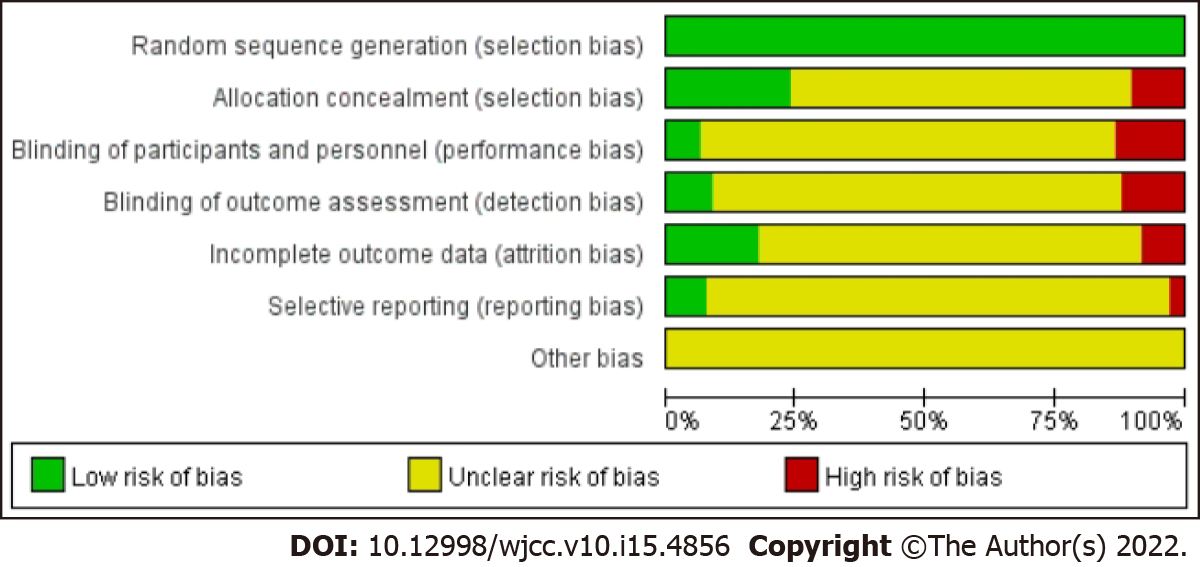

Two review authors (Lyu Z and Bai Y) assessed potential risks of bias for all included studies using Cochrane’s tool for assessing the risk of bias. The tool assesses bias in six different domains: Sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias. Each domain receives a score of high, low or unclear depending on each review author’s judgment. A third review author (Zhong LL) acted as an adjudicator in the event of a disagreement. Where doubt existed as to a potential risk of bias, we contacted the study authors for clarification. Results were tabulated into a "risk of bias graph" and a "risk of bias summary table".

In this meta-analysis, odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) was considered as the effect size for dichotomous outcomes; mean differences (MD) with 95%CI were calculated as the effect size for continuous outcomes. Forest plots were produced to visually assess the effect size and corresponding 95%CI using random-effects models. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed via the forest plot, while I2 values described the total variation between studies. When I2 values > 50%, it indicates high heterogeneity[11]. Subgroup analyses were used to explore and interpret the sources of heterogeneity; to evaluate whether the effects were modified by treatment characteristics and study quality, we specified it based on CHM ingredients, western medicine treatment and high-quality study. We used sensitivity analyses to explore the sources of high heterogeneity. Funnel plots, Begg’s test, and Egger’s test would be adopted to detect publication bias only when at least 10 studies were reporting the primary outcomes[12]. Statistical analysis was performed with RevMan software (version 5.4; The NordicCochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration), and STATA software, version 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

The meta-analysis outcomes of each outcome and subgroup are reported in Table 1.

| Outcomes | No. of studies in meta-analysis | No. of participants | Results | Heterogeneity | |||||

| T | C | OR/MD | 95%CI | P value | Chi- square test | I2 | P value | ||

| ER | 97 | 4455 | 4238 | 3.62 | (3.19, 4.11) | < 0.00001 | 85.79 | 0% | 0.76 |

| PEG | 31 | 1429 | 1399 | 2.42 | (1.91, 3.08) | < 0.00001 | 28.03 | 0% | 0.57 |

| Mosapride | 21 | 881 | 834 | 3.49 | (2.67, 4.56) | < 0.00001 | 14.87 | 0% | 0.78 |

| Lactulose | 24 | 1102 | 1018 | 3.71 | (2.86, 4.82) | < 0.00001 | 11.17 | 0% | 0.98 |

| Phenolphthalein | 7 | 294 | 287 | 4.59 | (2.71, 7.76) | < 0.00001 | 1.13 | 0% | 0.98 |

| Probiotics | 8 | 410 | 362 | 4.95 | (3.21, 7.65) | < 0.00001 | 0.63 | 0% | 1 |

| Placebo | 6 | 339 | 338 | 7.09 | (4.83, 10.43) | < 0.00001 | 4.84 | 0% | 0.44 |

| GS | 78 | 3438 | 3288 | 4.03 | (3.49, 4.65) | < 0.00001 | 70.74 | 0% | 0.68 |

| PEG | 26 | 1078 | 1038 | 2.69 | (2.06, 3.51) | < 0.00001 | 21.54 | 0% | 0.66 |

| Mosapride | 17 | 714 | 673 | 3.98 | (2.93, 5.41) | < 0.00001 | 10.92 | 0% | 0.81 |

| Lactulose | 23 | 1046 | 978 | 3.89 | (2.97, 5.09) | < 0.00001 | 8.08 | 0% | 1 |

| Phenolphthalein | 1 | 57 | 57 | 5.85 | (1.22, 28.05) | 0.03 | - | - | - |

| Probiotics | 6 | 234 | 234 | 6.21 | (3.60, 10.70) | < 0.00001 | 1.83 | 0% | 0.87 |

| Placebo | 5 | 309 | 308 | 8.4 | (5.64, 12.52) | < 0.00001 | 3.87 | 0% | 0.42 |

| BM | 15 | 663 | 652 | 0.83 | (0.67, 0.98) | < 0.00001 | 71.74 | 80% | < 0.00001 |

| PEG | 6 | 264 | 258 | 0.65 | (0.28, 1.02) | 0.0006 | 37.91 | 87% | < 0.00001 |

| Mosapride | 5 | 215 | 210 | 0.94 | (0.64, 1.24) | < 0.00001 | 15.43 | 74% | 0.004 |

| Lactulose | 1 | 55 | 55 | 0.98 | (0.81, 1.15) | < 0.00001 | - | - | - |

| Phenolphthalein | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Probiotics | 1 | 30 | 30 | 0.61 | (0.39, 0.83) | - | - | - | - |

| Placebo | 2 | 99 | 99 | 0.99 | (0.87, 1.11) | < 0.00001 | 0 | 0% | 1 |

| BSS | 7 | 303 | 284 | 1.63 | (1.15, 2.32) | 0.006 | 1.77 | 0% | 0.94 |

| PEG | 4 | 187 | 183 | 1.48 | (0.96, 2.28) | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0% | 0.76 |

| Mosapride | 2 | 60 | 61 | 1.88 | (0.79, 4.44) | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0% | 0.92 |

| Lactulose | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Phenolphthalein | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Probiotics | 1 | 56 | 40 | 2.07 | (0.90, 4.74) | 0.09 | - | - | - |

| Placebo | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

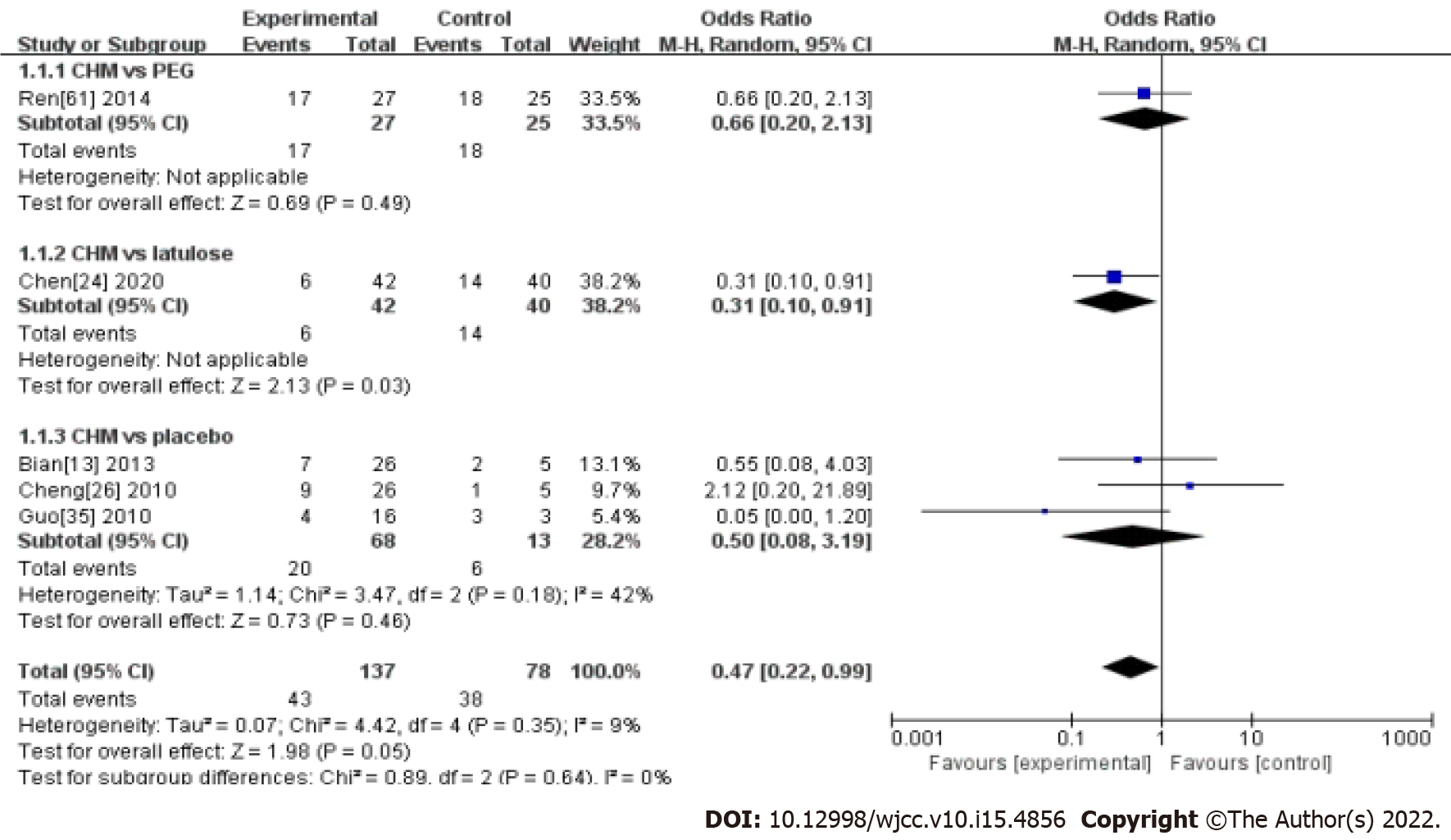

| Recurrence | 5 | 137 | 78 | 0.47 | (0.22, 0.99) | 0.05 | 4.42 | 9% | 0.35 |

| PEG | 1 | 27 | 25 | 0.66 | (0.20, 2.13) | 0.49 | - | - | - |

| Mosapride | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lactulose | 1 | 42 | 40 | 0.31 | (0.10, 0.91) | 0.03 | - | - | - |

| Phenolphthalein | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Probiotics | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Placebo | 3 | 68 | 13 | 0.5 | (0.08, 3.19) | 0.46 | 3.47 | 42% | 0.18 |

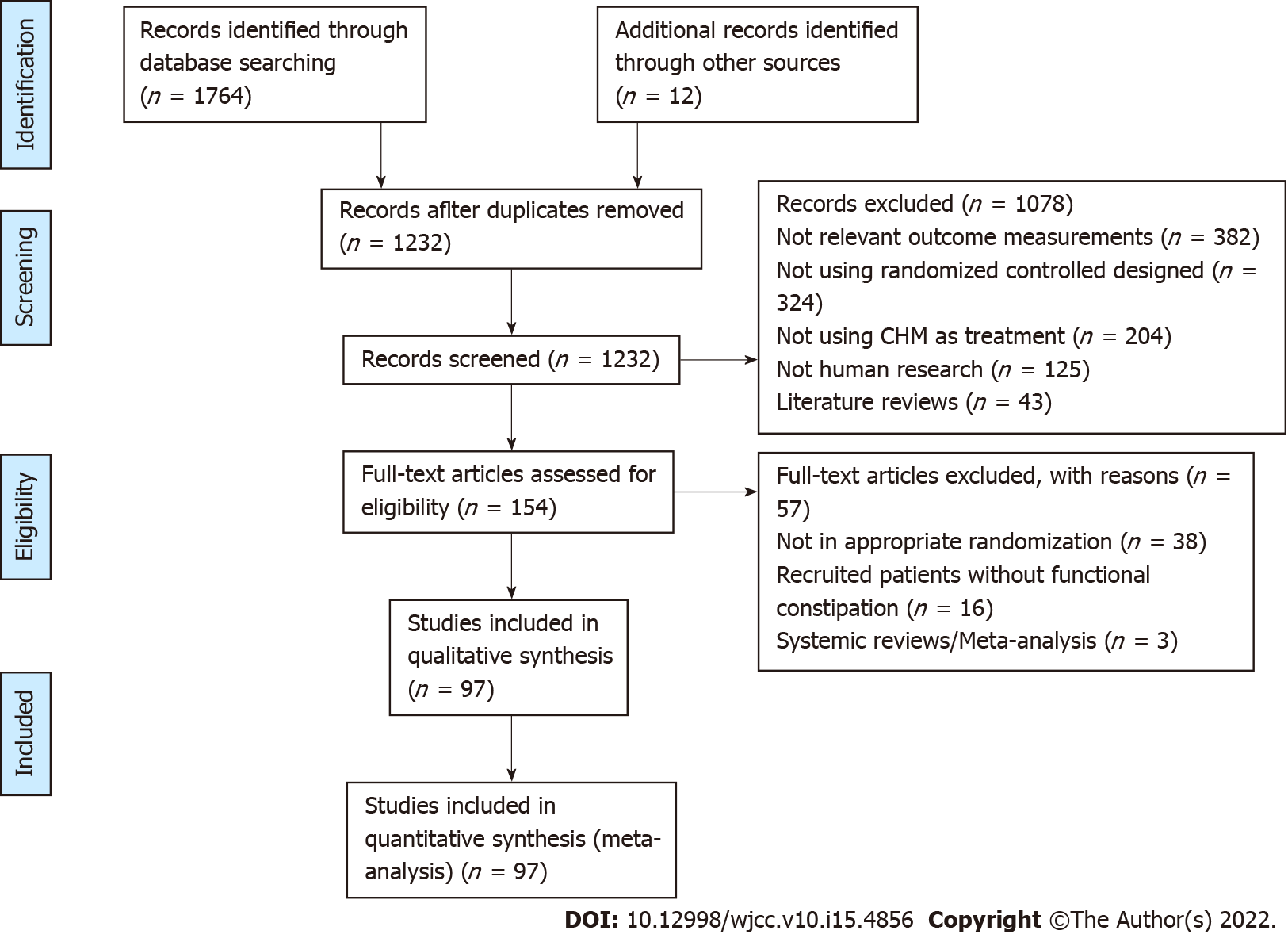

There were 1764 studies via electronic databases and 12 trials by supplementary retrieval of reference lists of relevant literature. After the deletion of duplicate records, 1232 trials were screened, and 1078 trials were excluded by reviewing titles and abstracts. The remaining 154 trials were reviewed by full text. Ultimately, 97 trials involving 8693 FC patients were included in this work. The selection process of research was detailed by the PRISMA flow diagram as shown in Figure 1.

Ninety-seven studies were included based on the eligibility criteria in this work. The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. As shown in Table 2, five studies[13,26,35,40,108] were published in English, the others in Chinese. Five studies[17,50,68,72,77] included patients using the Rome II criteria, 15 studies[16,25,36,38,42,44,49,58,62,63,67,82,83,90,95] using the Rome IV criteria, whereas the other 70 studies using Rome III criteria. The intervention of the treatment group was reported as CHM, and the ingredients were shown in Supplementary material 2. Besides, 6 types of intervention of the control group included PEG, mosapride, lactulose, phenolphthalein, probiotics and placebo. Duration in the retrieved studies ranged from 1 to 8 wk. Efficacy rate was reported in 97 studies and the global symptom was available in 69 studies. Bowel movement was reported in 15 studies. The recurrence rate within the follow-up period was reported in 5 studies. Bristol Stool Scale was available in 7 studies while adverse effects of CHM were reported in 26 studies. Characteristics of the included trials are listed in Table 2 and quality evaluations of the included trials are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2.

| Study | Language | Inclusion criteria | No. of participants | Age median (range) | Intervention of treatment group | Intervention of control group | Duration in wk | Assessment of outcomes | Follow-up in mo | Dropout (T/C) | Cochrane |

| Bian et al[13], 2014 | English | Rome III | 120 | 55.6 (18-75) | CHM | Placebo | 8 | ER, BM, GS, ARs, RR | 2 | 1/1 | A |

| Bin et al[14], 2011 | Chinese | Rome III | 61 | 67.4 (60-85) | CHM | Mosapride | 2 | ER, BM, BSS, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Bu et al[15], 2019 | Chinese | Rome III | 57 | 57.9 (40-85) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS, ARs | NA | NA | B |

| Cai et al[16], 2020 | Chinese | Rome IV | 60 | 48.2 (45-78) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Cao et al[17], 2012 | Chinese | Rome II | 60 | 36.7 (18-65) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Chen et al[18], 2011 | Chinese | Rome III | 76 | 74.3 (60-92) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, GS | NA | NA | C |

| Chen et al[19], 2012 | Chinese | Rome III | 70 | 31.9 (28-75) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Chen et al[20], 2014 | Chinese | Rome III | 120 | 69.3 (60-75) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS, ARs | NA | NA | B |

| Chen et al[21], 2014 | Chinese | Rome III | 88 | 25.1 (17-55) | CHM | Mosapride | 3 | ER, GS | 2 | NA | B |

| Chen et al[22], 2016 | Chinese | Rome III | 112 | 62.5 (51-70) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, BM, GS | NA | 1/1 | B |

| Chen et al[23], 2018 | Chinese | Rome III | 120 | 49.2 (25-77) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS | 1 | NA | B |

| Chen et al[24], 2020 | Chinese | Rome III | 88 | 66.9 (60-75) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS, RR | 1 | 2/4 | B |

| Chen et al[25], 2020 | Chinese | Rome IV | 160 | 48.3 (37-52) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Cheng et al[26], 2010 | English | Rome III | 120 | 33.5 (18-65) | CHM | Placebo | 8 | ER, BM, GS, ARs, RR | 2 | 9/8 | A |

| Cheng et al[27], 2012 | Chinese | Rome III | 100 | 52.6 (23-67) | CHM | Mosapride | 4 | ER,GS | 3 | NA | C |

| Chi et al[28], 2010 | Chinese | Rome III | 70 | NA | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, BM, GS | NA | 0/1 | B |

| Deng et al[29], 2018 | Chinese | Rome III | 96 | 70.2 (50-85) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS | 1 | 3/3 | B |

| Dou et al[30], 2014 | Chinese | Rome III | 90 | 58.7 (45-72) | CHM | Lactulose | 3 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Fu et al[31], 2012 | Chinese | Rome III | 60 | 42.8 (18-65) | CHM | Probiotics | 4 | ER, BM, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Gao et al[32], 2013 | Chinese | Rome III | 60 | 55.7 (18-70) | CHM | Peg | 8 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Gao et al[33], 2015 | Chinese | Rome III | 80 | 58.3 (20-70) | CHM | Peg | 2 | ER, BM, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Gu et al[34], 2013 | Chinese | Rome III | 60 | 45.1 (21-60) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS, BSS, ARs | NA | 0/1 | B |

| Guo et al[35], 2010 | English | Rome II | 70 | 64.7 (21-79) | CHM | Placebo | 4 | ER, GS, RR, RR | NA | NA | B |

| Guo et al[36], 2018 | Chinese | Rome IV | 60 | 61.8 (18-80) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, GS | NA | 1/1 | B |

| He et al[37], 2015 | Chinese | Rome III | 80 | 71.4 (60-79) | CHM | Peg | 2 | ER, BM, GS | 2 | NA | B |

| He et al[38], 2019 | Chinese | Rome IV | 120 | 72.5 (65-80) | CHM | Peg | 2 | ER, GS, ARs | 2 | NA | B |

| Hu et al[39], 2018 | Chinese | Rome III | 238 | 3.84 (1-14) | CHM | Placebo | 1 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Huang et al[40], 2012 | English | Rome III | 60 | 71.8 (60-85) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS, ARs | NA | NA | B |

| Hui et al[41], 2018 | Chinese | Rome III | 62 | 68.1 (55-90) | CHM | Lactulose | ER, GS, ARs | NA | NA | NA | |

| Jiang et al[42], 2020 | Chinese | Rome IV | 72 | 51.6 (22-73) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Jiao et al[43], 2018 | Chinese | Rome III | 120 | 58.7 (50-70) | CHM | Placebo | 1 | ER, GS | NA | 0/4 | C |

| Kong et al[44], 2020 | Chinese | Rome IV | 100 | 69.4 (60-83) | CHM | Mosapride | 2 | ER, GS | 1 | 1/3 | B |

| Lai et al[45], 2012 | Chinese | Rome III | 90 | NA | CHM | Mosapride | 4 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Li et al[46], 2012 | Chinese | Rome III | 60 | 49.7 (18-65) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, GS | NA | NA | C |

| Li et al[47], 2015 | Chinese | Rome III | 166 | 51.9 (18-65) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, ARs | 2 | NA | B |

| Li et al[48], 2016 | Chinese | Rome III | 160 | 47.2 (23-68) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, BM | NA | 0/6 | B |

| Li et al[49], 2019 | Chinese | Rome IV | 120 | 55.1 (49-63) | CHM | Mosapride | 2 | ER, GS, ARs | NA | NA | B |

| Lin et al[50], 2009 | Chinese | Rome II | 120 | 68.5 (65-80) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, ARs | NA | NA | C |

| Lin et al[51], 2012 | Chinese | Rome III | 80 | 47.1 (20-60) | CHM | Mosapride | 6 | ER, GS, ARs | NA | NA | B |

| Liu et al[52], 2013 | Chinese | Rome III | 66 | 49.6 (18-75) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS | NA | 0/3 | B |

| Liu et al[53], 2017 | Chinese | Rome III | 60 | 51.9 (18-65) | CHM | Mosapride | 4 | ER, GS, ARs | NA | NA | B |

| Liu et al[54], 2017 | Chinese | Rome III | 120 | 53.7 (45-64) | CHM | Lactulose | 2.1 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Liu et al[55], 2018 | Chinese | Rome III | 244 | 2.6 (1-14) | CHM | Probiotics | 4 | ER | NA | NA | B |

| Lv et al[56], 2012 | Chinese | Rome III | 280 | 67.1 (19-82) | CHM | Peg | 3 | ER | 6 | NA | B |

| Lv et al[57], 2018 | Chinese | Rome III | 80 | 54.9 (20-71) | CHM | Probiotics | 1 | ER, GS | NA | NA | C |

| Mu et al[58], 2019 | Chinese | Rome IV | 90 | 68.7 (62-81) | CHM | Peg | 2 | ER, GS, BSS | NA | NA | B |

| Qian et al[59], 2014 | Chinese | Rome III | 80 | 46.3 (18-65) | CHM | Mosapride | 8 | ER, GS, ARs | NA | 2/4 | B |

| Que et al[60], 2018 | Chinese | Rome III | 80 | 45.8 (16-70) | CHM | Lactulose | 8 | ER, GS | NA | NA | C |

| Ren et al[61], 2014 | Chinese | Rome III | 60 | 47.6 (18-65) | CHM | Peg | 8 | ER, GS, RR | 1 | NA | B |

| Shao et al[62], 2019 | Chinese | Rome IV | 100 | 67.9 (65-80) | CHM | Mosapride | 2 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Su et al[63], 2019 | Chinese | Rome IV | 96 | 71.5 (64-78) | CHM | Mosapride | 2 | ER, BM | 1 | NA | B |

| Sui et al[64], 2012 | Chinese | Rome III | 120 | 54.9 (18-79) | CHM | Probiotics | 2 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Sun et al[65], 2011 | Chinese | Rome III | 80 | 68.3 (60-80) | CHM | Mosapride | 1 | ER, BM, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Tao et al[66], 2018 | Chinese | Rome III | 60 | NA | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER | NA | NA | B |

| Wang et al[67], 2020 | Chinese | Rome IV | 94 | 69.3 (66-85) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, BM, GS | 2 | 5/5 | B |

| Wang et al[68], 2004 | Chinese | Rome II | 90 | 64.5 (56-75) | CHM | Phenolphthalein | 4 | ER | NA | NA | B |

| Wang et al[69], 2011 | Chinese | Rome III | 156 | 60.7 (NA) | CHM | Peg | 2 | ER, GS, BSS | NA | NA | B |

| Wang et al[70], 2013 | Chinese | Rome III | 112 | 73.6 (65-82) | CHM | Lactulose | 3 | ER, ARs | NA | 0/12 | B |

| Wang et al[71], 2014 | Chinese | Rome III | 60 | 1.9 (1-7) | CHM | Probiotics | 8 | ER | 3 | NA | B |

| Wang et al[72], 2015 | Chinese | Rome II | 116 | 66.7 (55-75) | CHM | Phenolphthalein | 4 | ER, GS | NA | 1/1 | B |

| Wu et al[73], 2008 | Chinese | Rome III | 54 | 76.4 (60-84) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, GS | NA | 1/0 | B |

| Wu et al[74], 2009 | Chinese | Rome III | 60 | 55.9 (50-75) | CHM | Probiotics | 4 | ER, GS, ARs | 6 | NA | B |

| Wu et al[75], 2013 | Chinese | Rome III | 60 | 56.3 (45-75) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, BM, ARs | NA | 4/3 | B |

| Wu et al[76], 2013 | Chinese | Rome III | 60 | 49.4 (NA) | CHM | Phenolphthalein | 2 | ER | NA | NA | B |

| Xin et al[77], 2008 | Chinese | Rome II | 130 | 66.8 (60-88) | CHM | Phenolphthalein | 4 | ER | NA | 0/5 | B |

| Xin et al[78], 2014 | Chinese | Rome III | 70 | 69.7 (60-85) | CHM | Phenolphthalein | 4 | ER | NA | NA | B |

| Xu et al[79], 2013 | Chinese | Rome III | 82 | 70.3 (NA) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS | NA | NA | C |

| Xu et al[80], 2016 | Chinese | Rome III | 70 | 47.2 (18-75) | CHM | Peg | 8 | ER, GS | NA | 5/5 | B |

| Xu et al[81], 2018 | Chinese | Rome III | 80 | 41.8 (18-54) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, GS | 1 | 8/10 | B |

| Xu et al[82], 2019 | Chinese | Rome IV | 60 | 42.3 (25-64) | CHM | Mosapride | 4 | ER, GS | 3 | NA | B |

| Yan et al[83], 2020 | Chinese | Rome IV | 80 | 46.7 (16-70) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, GS | 2 | NA | B |

| Yan et al[84], 2013 | Chinese | Rome II | 258 | 82.2 (80-93) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER | NA | NA | B |

| Yan et al[85], 2016 | Chinese | Rome III | 60 | 43.1 (32-62) | CHM | Mosapride | 4 | ER, GS, BSS | 1 | NA | B |

| Yang et al[86], 2008 | Chinese | Rome III | 80 | 67.4 (60-82) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Yang et al[87], 2012 | Chinese | Rome III | 66 | 71.5 (NA) | CHM | Phenolphthalein | 2 | ER | NA | 2/2 | C |

| Yang et al[88], 2015 | Chinese | Rome III | 80 | 54.9 (NA) | CHM | Probiotics | 4 | ER, GS, BSS, ARs | NA | NA | B |

| Yao et al[89], 2016 | Chinese | Rome III | 160 | 66.1 (60-80) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Ye et al[90], 2020 | Chinese | Rome IV | 120 | 57.8 (18-78) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Ye et al[91], 2016 | Chinese | Rome III | 60 | 68.4 (60-85) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Yuan et al[92], 2016 | Chinese | Rome III | 64 | 47.4 (30-75) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, GS, ARs | 1 | NA | B |

| Zeng et al[93], 2017 | Chinese | Rome III | 88 | 47.2 (18-65) | CHM | Mosapride | 4 | ER, BM, GS | 3 | 1/3 | B |

| Zhan et al[94], 2016 | Chinese | Rome III | 60 | 56.3 (18-75) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS, ARs | NA | NA | B |

| Zhang et al[95], 2020 | Chinese | Rome IV | 80 | 44.5 (18-65) | CHM | Lactulose | 4 | ER, GS, ARs | 3 | 5/5 | B |

| Zhang et al[96], 2014 | Chinese | Rome III | 64 | 56.7 (18-75) | CHM | Mosapride | 4 | ER, ARs | NA | NA | B |

| Zhang et al[97], 2014 | Chinese | Rome III | 104 | 68.2 (60-80) | CHM | Mosapride | 4 | ER, GS, ARs | 1 | NA | B |

| Zhang et al[98], 2014 | Chinese | Rome III | 90 | 65.3 (NA) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, GS | NA | NA | C |

| Zhang et al[99], 2018 | Chinese | Rome III | 60 | 72.4 (60-85) | CHM | Phenolphthalein | 4 | ER | NA | NA | C |

| Zhang et al[100], 2018 | Chinese | Rome III | 106 | 33.5 (24-58) | CHM | Mosapride | 8 | ER, BM | 1 | 0/2 | B |

| Zhang et al[101], 2019 | Chinese | Rome III | 68 | 41.7 (19-69) | CHM | Probiotics | 4 | ER, GS | 3 | NA | B |

| Zhao et al[102], 2009 | Chinese | Rome III | 76 | 42.4 (NA) | CHM | Mosapride | 2 | ER, GS | 1 | 11/11 | B |

| Zhao et al[103], 2014 | Chinese | Rome III | 76 | 56.7 (15-80) | CHM | Peg | 4 | ER, GS | NA | NA | C |

| Zhao et al[104], 2015 | Chinese | Rome III | 68 | 51.4 (18-70) | CHM | Mosapride | 4 | ER, GS, ARs | NA | NA | B |

| Zhao et al[105], 2015 | Chinese | Rome III | 100 | 4.2 (1-14) | CHM | Lactulose | 8 | ER, GS | 14 | 1/2 | B |

| Zhao et al[106], 2018 | Chinese | Rome III | 90 | 53.7 (23-67) | CHM | Lactulose | 8 | ER, GS | NA | NA | B |

| Zhao et al[107], 2019 | Chinese | Rome III | 66 | 68.4 (65-84) | CHM | Peg | 3 | ER, BSS | 3 | 0/1 | C |

| Zhong et al[108], 2018 | English | Rome III | 194 | 44.6 (18-70) | CHM | Placebo | 8 | ER, BM, GS, ARs | 2 | 3/7 | A |

| Zhou et al[109], 2018 | Chinese | Rome III | 80 | 51.3 (30-70) | CHM | Mosapride | 4 | ER, GS, ARs | NA | 7/9 | B |

Among the 97 studies included, 3 trials[13,26,108] were found to be of high methodological quality. Thirteen trials[18,27,43,46,50,57,60,79,87,98,99,103,107] were deemed to have a high risk of bias. All trials mentioned “random” in terms of allocation, but 12 trials[18,43,46,50,57,60,79,87,98,99,103,107] didn’t describe the specific method of randomization. Five trials[13,26,53,61,108] described allocation concealment and used blinding of participants, personnel or outcome assessors. Drop-outs and withdrawals were reported in 5 trials[13,19,24,26,108] which just left out the cases without qualified result data. We considered 8 trials[18,50,57,60,79,98,103,107] to be of selective reporting bias as these trials failed to report all the prespecified outcomes mentioned in their method section. Other potential sources of bias considered in all included studies were unclear. Therefore, study methodologies were incompletely described in majorities. The result of the assessment was showed in Figure 2, and the detail was showed in Supplementary material 3.

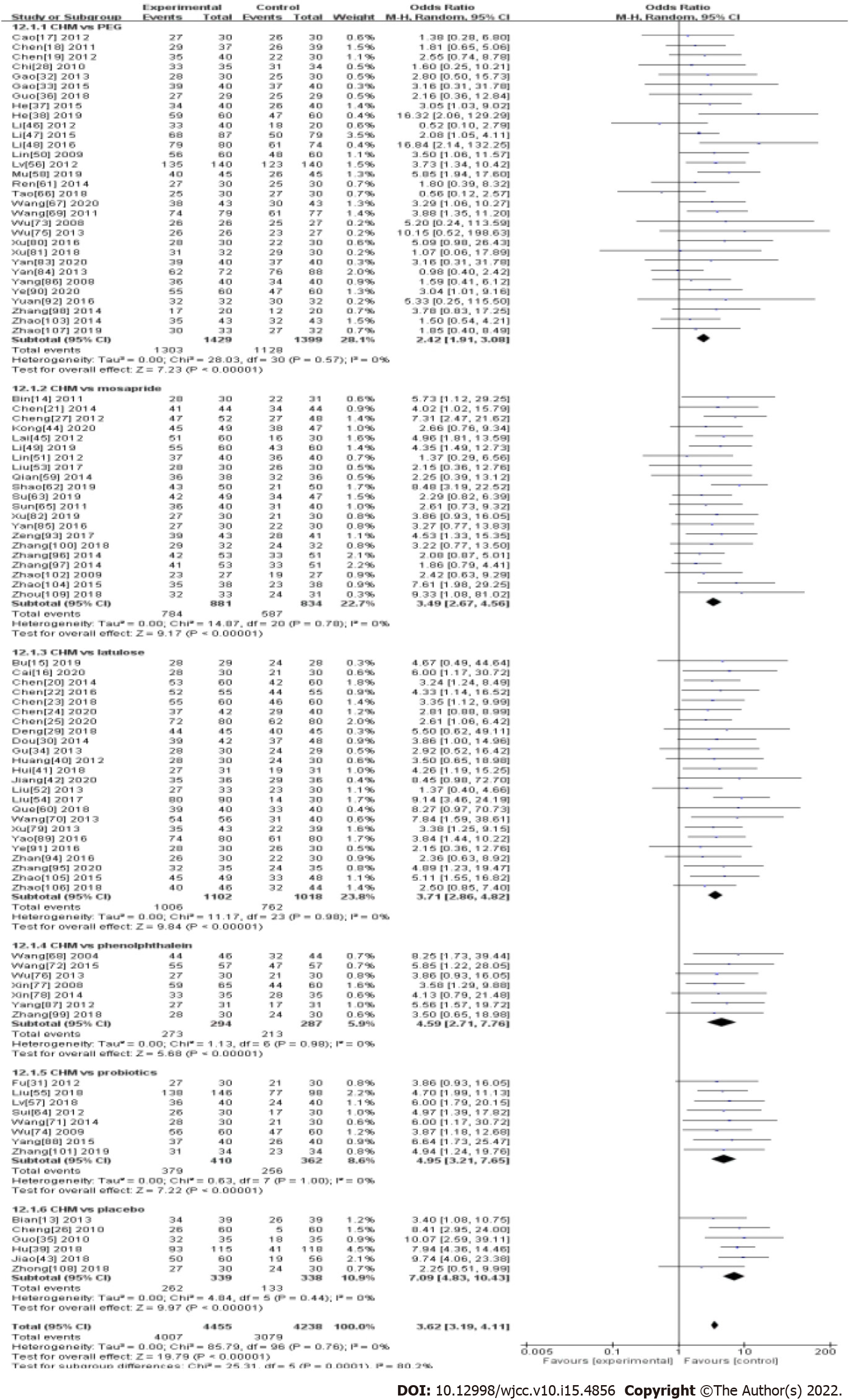

Ninety-seven studies measured ER (89.9%; 4007/4455) patients in the Chinese herbal medicine treatment group and 72.7% (3079/4238) patients with western medicine were measured. Results from 97 studies showed the treatment for FC was significantly in favor of CHM (OR: 3.62, 95%CI: 3.19-4.11, P < 0.00001) (Table 1 and Figure 3). There was no significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.76).

In the subgroup analysis, CHM had a significant effect compared with PEG (OR: 2.42, 95%CI: 1.91-3.08, P < 0.00001), mosapride (OR: 3.49, 95%CI: 2.67-4.56, P < 0.00001), lactulose (OR: 3.71, 95%CI: 2.86-4.82, P < 0.00001), phenolphthalein (OR: 4.59, 95%CI: 2.71-7.76, P < 0.00001), probiotics (OR: 4.95, 95%CI: 3.21-7.65, P < 0.00001), and specifically compared with placebo (OR: 7.09, 95%CI: 4.83-10.43, P < 0.00001). There was no significant heterogeneity between studies in each subgroup (Table 1 and Figure 3).

Seventy-eight studies measured GS, and the results showed the treatment for FC was significantly in favor of CHM (OR: 4.03, 95%CI: 3.49-4.65, P < 0.00001) (Table 1 and Supplementary material 4). There was no significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.68). In the subgroup analysis, CHM had a significant effect compared with PEG (OR: 2.69, 95%CI: 2.06-3.51, P < 0.00001), mosapride (OR: 3.98, 95%CI: 2.93-5.41, P < 0.00001), lactulose (OR: 3.89, 95%CI: 2.97-5.09, P < 0.00001), probiotics (OR: 6.21, 95%CI: 3.60-10.70, P < 0.00001), and specifically compared with placebo (OR: 8.40, 95%CI: 5.64-12.52, P < 0.00001). There was no significant heterogeneity between studies in each subgroup (Table 1 and Supplementary material 4). However, there was only one study that compared the global symptom between CHM and phenolphthalein (OR: 5.85, 95%CI: 1.22-28.05).

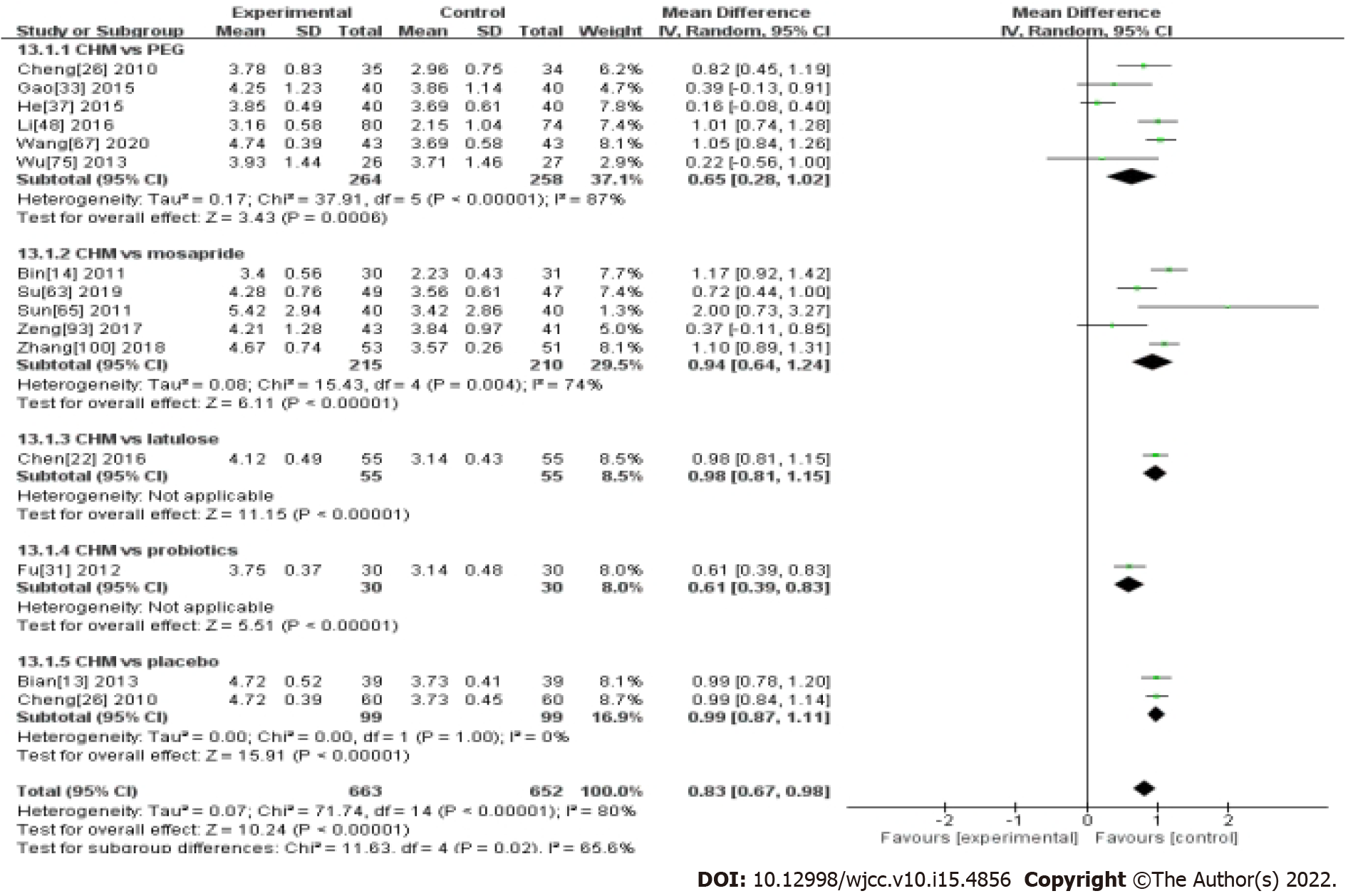

Fifteen studies measured BM. Results from 15 studies showed the treatment for FC was significantly in favor of CHM (MD 0.83, 95%CI: 0.67-0.98, P < 0.00001) (Table 1 and Figure 4). There was significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 80%, P < 0.00001).

In the subgroup analysis, CHM had a significant effect compared with PEG (MD 0.83, 95%CI: 0.67-0.98, P < 0.0006), mosapride (MD 0.65, 95%CI: 0.28-1.02, P < 0.00001), and specifically compared with placebo (MD 0.99, 95%CI: 0.87-1.11, P < 0.00001). There was no significant heterogeneity between studies in the placebo subgroup (Table 1 and Figure 4). However, there was only one study that compared CHM with lactulose (MD 0.98, 95%CI: 0.81-1.15, P < 0.00001), and probiotics (MD 0.61, 95%CI: 0.39-0.83, P < 0.00001). No study in the phenolphthalein subgroup.

A total of 7 studies compared CHM with western medicine and reported the Bristol Stool Scale. The results showed the treatment for FC was significantly in favor of CHM (OR: 1.63, 95%CI: 1.15-2.32, P < 0.006) (Table 1 and Supplementary material 5). There was no significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.94).

In the subgroup analysis, CHM had no significant effect compared with PEG (OR: 1.48, 95%CI: 0.96-2.28, P = 0.15) and mosapride (OR: 1.88, 95%CI: 0.79-4.44, P = 0.15). There was no significant heterogeneity between studies in the two subgroups (Table 1 and Supplementary material 5). However, there was only one study that compared CHM with probiotics (OR: 2.07, 95%CI: 0.90-4.74, P = 0.09).

Five studies compared CHM with western medicine and reported the RR. The results showed CHM was not superior to western medicine in controlling the recurrence rate of FC (OR: 0.47, 95%CI: 0.22-0.99, P = 0.05) (Table 1 and Figure 5). There was no significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 9%, P = 0.35).

In the subgroup analysis, CHM had no significant effect compared with placebo (OR: 0.5, 95%CI: 0.08-3.19, P = 0.46). There was no significant heterogeneity between studies in this subgroup (Table 1 and Figure 5). However, there was only one study that compared CHM with PEG (OR: 0.66, 95%CI: 0.20-2.13, P = 0.49), and lactulose (OR: 0.31, 95% CI 0.10-0.91, P = 0.03) (Table 1 and Figure 5).

Ten trials[13,17,19,26,33,38,46,79,81,90] reported digestive symptoms when using CHM, including abdominal pain or bloating, nausea, stomach discomfort, diarrhea and passing of gas. There were also other adverse effects recorded in CHM groups, such as headache[17,81], transient hypertension[35] and insomnia[81]. While 21 studies[13,15,19,25,26,29,33,35,38-39,46,54,55,68,70,79,81,85,86,94,107] had diges

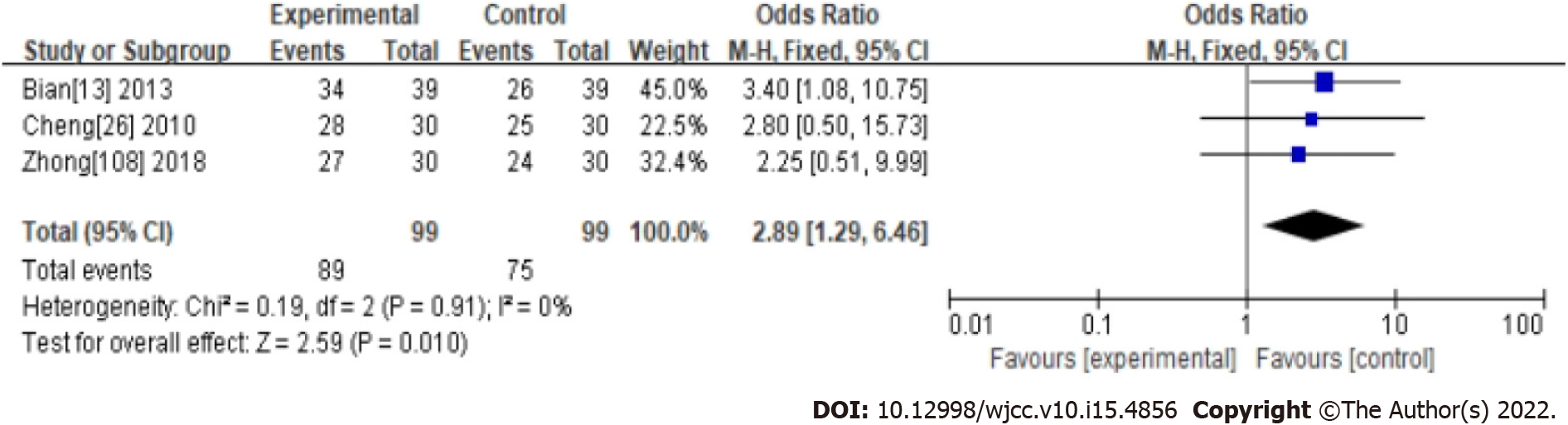

Three studies were evaluated as high quality with a low risk of bias in their methodology. Their compared CHM with western medicine and reported ER. Results showed the treatment for FC was significantly in favor of CHM (OR: 2.89, 95%CI: 1.29-6.46, P < 0.01) (Table 1 and Figure 6). There was no significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.94).

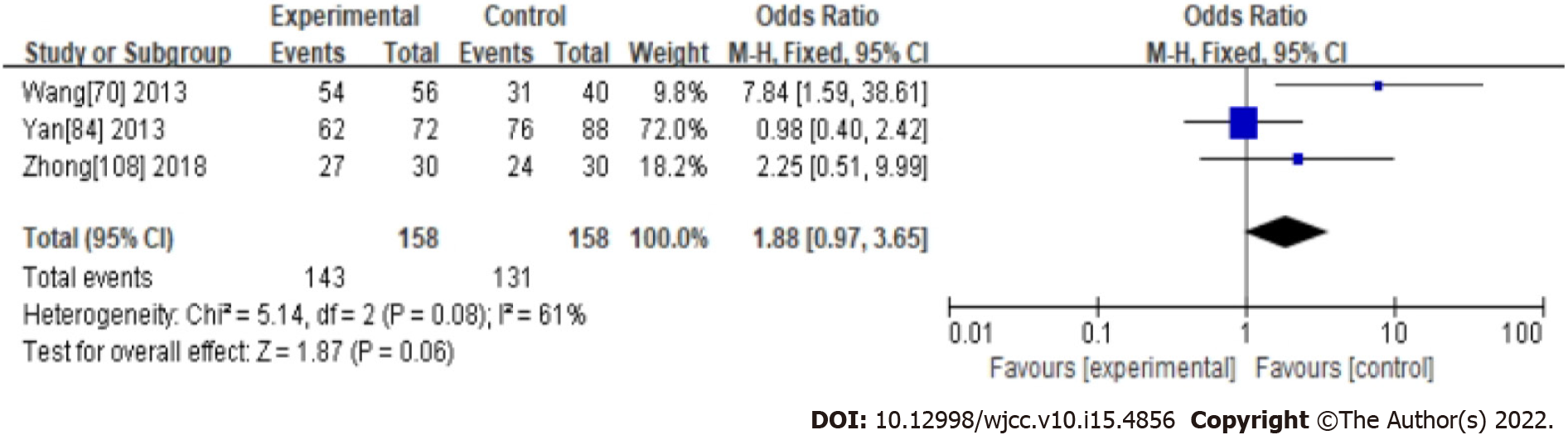

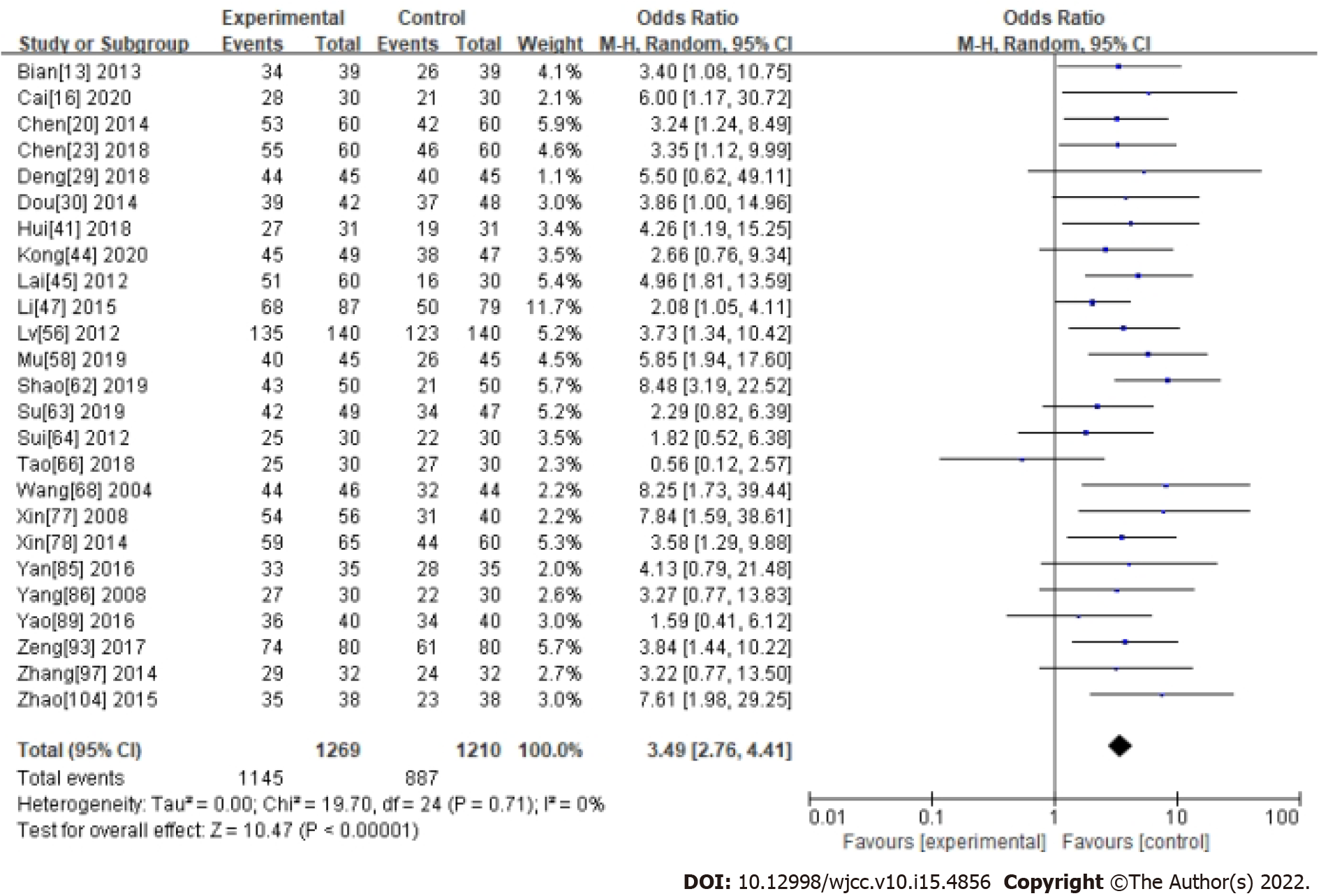

Two CHM ingredients commonly used in the treatment of functional constipation, Cannabis Fructus and Cistanche, were analyzed in a subgroup by measuring ER. In the Cannabis Fructus subgroup, the results showed Cannabis Fructus had no significant effect compared with western medicine (OR: 1.88, 95%CI: 0.97-3.65, P = 0.06). There was significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 61%, P = 0.08) (Supplementary material 1 and Figure 7). In the Cistanche subgroup, the results showed Cistanche had a significant effect compared with western medicine (OR: 3.49, 95%CI: 2.76-4.41, P < 0.0001). There was significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.71) (Supplementary material 1 and Figure 8).

Visual inspection of funnel plots (Figure 9), Begg’s test (P = 0.31), and Egger’s test (P = 0.26) revealed no evidence of publication bias for the examined primary outcomes. We did sensitivity analyses by excluding seven trials[17,19,64,76,87,96,103] using the decoction; the outcome showed that the results did not change.

A total of 97 RCTs involving 8693 patients with FC were recruited in the review. Pooled data showed a tendency for improvement of clinical efficacy in the CHM group, compared with most Western medicine, such as PEG, mosapride, lactulose, phenolphthalein, probiotics and placebo. The results showed that CHM was significantly superior to western medicines in improving efficacy rate, the frequency of bowel movement, global symptom assessment, and Bristol Stool Scale score of FC. However, there was significant heterogeneity between the 7 studies that reported the frequency of bowel movement (I2 = 80%, P < 0.00001). Besides, five studies compared CHM with western medicine and reported the recurrence rate showed the treatment for functional constipation was not significantly in favor of CHM.

Our study found that CHM treatment of FC significantly improved physical symptoms, including constipation-related symptoms (abdominal distension, reduced bowel frequency, difficulty defecating) and systemic symptoms (dry mouth, insomnia, and dyspepsia), compared to Western medicine or placebo. Similar findings have been found in related studies[110,111]: They found that herbal medicine can produce synergistic therapeutic effects, such as spasmolytic, tonifying, wind-repelling, anti-inflammatory and local analgesia. We believe that TCM can effectively address the challenge of simultaneously addressing multiple symptoms other than constipation faced by Western medicine in the treatment of FC. However, how to evaluate and quantify the improvement of functional constipation symptoms from the perspective of TCM. Huang et al[112,113] proposed the use of Multidimensional Item Response Theory to solve the problem of standardized results of TCM symptoms.

The normal frequency of defecation is 3 to 21 times per week[114,115]. A recent meta-analysis showed that osmotic and irritant laxatives increased stool frequency by 2.5 times per week in patients with FC[116]. Our study found that CHM had a significant effect compared with PEG (MD 0.83, 95%CI: 0.67-0.98, P < 0.0006). However, six studies were included in this meta-analysis, and significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 87%, P < 0.00001). The strong conclusion that CHM improves defecation frequency needs to be validated by more high-quality studies. At the same time, we found that many current RCTs recorded stool frequency, but translated into effective results at the time of reporting. This leads to a lack of detailed data on stool frequency. Our study, therefore, suggests that similar future studies should report detailed stool frequency and compare them to baseline, such as Zhong et al’s study[108].

Despite beneficial findings from meta-analyses, the results of these trials should be interpreted with caution due to the generally low methodological quality of the included studies. Although only RCTs were included, with insufficient information on how the random allocation was generated and/or concealed in most studies, it was uncertain about selection bias. Secondly, considering clinical efficacy was a subjective index and it could introduce performance bias and detection bias without blinding participants, healthcare providers and assessors. Thirdly, missing data due to attrition or exclusions was found in some studies but only a few handled it appropriately. Finally, protocols were not available to confirm free of selective reporting. For all these reasons, further validation of the findings is necessary. Besides, longer follow-up (> 12 wk) is necessary taking the placebo effect into account[117].

For the safety of CHM, adverse effects were reported, such as abdominal pain or bloating, nausea, stomach discomfort, diarrhea and passing of gas. But there were only 12.4% (12/97) of studies mentioned the safety of interventions or the AEs investigated as one of the main outcome indicators. In addition, many traditional Chinese medicines have been widely used by Chinese traditional medicine practitioners for nearly two millennia. This supports their security. Therefore, more attention should be paid to recording and reporting the harmful effects of these interventions.

We searched main English and Chinese databases under well-designed searching strategies and made the comparison between CHM and different WM therapies clearer. There are several limitations to this systematic review. Firstly, missing articles that might be relevant. Although we searched through databases and did not limit the language of the article, we may still miss relevant articles in regional journals. Because the articles published in these regional magazines are not included in the database we searched. Secondly, most of the studies we included were published only in Chinese, which limited readers' review of the original research. This situation may be improved with the worldwide promotion of CHM. Thirdly, the studies we included were all conducted in the Asian region so the extrapolation of these results is limited by geography.

In conclusion, in this meta-analysis, we found that CHM may have potential benefits in increasing the number of bowel movements, improving stool characteristics, and alleviating global symptoms in FC patients. However, a firm conclusion could not be reached because of the poor quality of the included trials. Well-designed and high-quality reported RCTs are needed to confirm more definitive conclusions in the future.

Well-designed and high-quality reported randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to confirm more definitive conclusions in the future.

A firm conclusion could not be reached because of the poor quality of the included trials.

Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) may have potential benefits in increasing the number of bowel movements, improving stool characteristics and alleviating global symptoms in functional constipation (FC) patients.

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of CHM on efficacy rate, global symptoms, bowel movements, and the Bristol Stool Scale score in patients with FC by summarizing current available RCTs.

This review aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of CHM in patients with FC.

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of CHM in patients with FC.

FC is a common and chronic gastrointestinal disease.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Davis J, United States; Sánchez JIA, Colombia S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Cheng C, Chan AO, Hui WM, Lam SK. Coping strategies, illness perception, anxiety and depression of patients with idiopathic constipation: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:319-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Huang R, Ho SY, Lo WS, Lam TH. Physical activity and constipation in Hong Kong adolescents. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nellesen D, Yee K, Chawla A, Lewis BE, Carson RT. A systematic review of the economic and humanistic burden of illness in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic constipation. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19:755-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Belsey J, Greenfield S, Candy D, Geraint M. Systematic review: impact of constipation on quality of life in adults and children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:938-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Basilisco G, Coletta M. Chronic constipation: a critical review. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:886-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Johanson JF, Kralstein J. Chronic constipation: a survey of the patient perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:599-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 374] [Cited by in RCA: 438] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McRorie JW, Daggy BP, Morel JG, Diersing PS, Miner PB, Robinson M. Psyllium is superior to docusate sodium for treatment of chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:491-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lin LW, Fu YT, Dunning T, Zhang AL, Ho TH, Duke M, Lo SK. Efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine for the management of constipation: a systematic review. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:1335-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tan N, Gwee KA, Tack J, Zhang M, Li Y, Chen M, Xiao Y. Herbal medicine in the treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:544-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13930] [Cited by in RCA: 13355] [Article Influence: 834.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21630] [Cited by in RCA: 25802] [Article Influence: 1121.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Irwig L, Macaskill P, Berry G, Glasziou P. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Graphical test is itself biased. BMJ. 1998;316:470; author reply 470-470; author reply 471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34245] [Cited by in RCA: 40546] [Article Influence: 1448.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Bian ZX, Cheng CW, Zhu LZ. Chinese herbal medicine for functional constipation: a randomised controlled trial. Hong Kong Med J. 2013;19 Suppl 9:44-46. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Bin DH, Wang AH. Clinical observation of Yiqi Ziyin Decoction for the treatment of senile slow transit constipation. Zhongyiyao Daobao. 2011;17:31-33. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Bu F, Li MY, Gu YF. Effect of Jichuan Decoction combined with Zhizhu Pill on chronic functional constipation in middle-aged and elder lypatients. Xiandai ZhongxiyiJiehe Zazhi. 2019;28:15-18. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cai XL. Effect of Jichuan decoction on functional constipation in middle-aged and elderly. Shiyong ZhongxiyiJiehe Linchuang Zazhi. 2020;20:17-18. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Cao YL. An efficacy observation of Tong Bian Capsule for the treatment of senile functional constipation. Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, 2012. Available from: http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10199-1012420467.htm. |

| 18. | Chen H, Fan KH, Yu BT, Zhao T. Clinical controlled observation of treatment of senile chronic functional constipation with polyethylene glycol 4000 and Maren pill. Xibu Yixue Zazhi. 2011;23:2168-2169. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Chen M. Stomach medicine on the treatment of functional constipation clinical observation. Hubei University of Chinese Medicine, 2012. Available from: http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10507-1012488078.htm. |

| 20. | Chen H, Zhu HP, Li XL, Lin W. G. An efficacy observation of Run Chang Wan for the treatment of functional constipation with the elderly in 60 cases. Zhongyi Yanjiu Zazhi. 2014;27:13-15. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Chen P, Liu ZR, Lu JM. Clinical observation of Wenshen Shugan Decoction for the treatment of slow transit constipation in 44 cases. Henan Zhongyi Zazhi. 2014;34:1351-1352. |

| 22. | Chen D, Guan XM. Jinkui Shenqi Decoction in the treatment of 55 cases of functional constipation of spleen and kidney Yang deficiency. Sichuan Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2016;34:92-94. |

| 23. | Chen YW, Zhang Q. Clinical study on 60 cases of chronic functional constipation treated with Shenqi Marong Decoction. Linchuang YiyaoWenxian Dianzi Zazhi. 2018;5:120-122. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Chen FR. Clinical Observation on the Therapeutic Effect of "Fu-Disease viscera-Viscera treatment" on functional constipation in the elderly with deficiency of Qi and Yin. Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2020. Available from: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=1020633792.nh&DbName=CMFD2020. |

| 25. | Chen L, Zhang Y. Curative Effect observation of 80 cases of functional constipation with modified Atractylode Decoction. Zhejiang Zhongyi Zazhi. 2020;55:578-579. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Cheng CW, Bian ZX, Zhu LX, Wu JC, Sung JJ. Efficacy of a Chinese herbal proprietary medicine (Hemp Seed Pill) for functional constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:120-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cheng SP, Zheng QJ, Li YQ. Clinical research on Zhizhu Decoction in the treatment of chronic functional constipation. Zhongyi Xuebao. 2012;27:1023-1025. |

| 28. | Chi YH, Jiang MH. Clinical research on functional constipation treated by Mixture Linggu. Liaoning Zhongyiyao Daxue Xuebao. 2010;12:99-101. |

| 29. | Deng YX. Clinical observation on the treatment of functional constipation in the elderly by warming Yang and guiding stagnation. Shijie KexueJishu Zhongyiyao Xiandaihua Zazhi. 2018;20:994-996. |

| 30. | Dou J, Guo J, Li RW. Clinical observation of the method of Tongyun Wuzang for the treatment of senile functional constipation. Jilin. 34:262-264. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Fu K. Clinical observation on Zengye Yuanchang decoction in treating syndrome of deficiency of both qi and yin of slow transit constipation. Hunan University of Chinese Medicine, 2012. Available from: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=163c4b9a8adbada36c2b5a048bd8149c&site=xueshu_se&hitarticle=1. |

| 32. | Gao CY. The clinical experiment trails on modified Huang QI Jian Zhong Decoction in treating functional constipation with the weak syndrome of the stomach and spleen. Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2013. Available from: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=18b01e7746f395c65509de5f070e35aa&site=xueshu_se&hitarticle=1. |

| 33. | Gao M, Wang W. Clinical observation on Jiawei Sanxiang Decoction in the treatment of Intestinal Qi stagnation and spleen deficiency type of functional constipation. Shijie Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2015;10:732-735. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 34. | Gu JY. Clinical observation of Sanren Runchang Formula in the treatment of slow transit functional constipation. Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, 2013. Available from: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=8e8776587839ede7f3de1fe413195a83&site=xueshu_se&hitarticle=1. |

| 35. | Jia G, Meng MB, Huang ZW, Qing X, Lei W, Yang XN, Liu SS, Diao JC, Hu SY, Lin BH, Zhang RM. Treatment of functional constipation with the Yun-chang capsule: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:487-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Guo HY. Clinical study on Huangyun Tongbian Decoction in functional therapy of Spleen-Lung-Qi Deficiency Constipation. Anhui University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2018. Available from: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=157v0t00dt2502m0sy4m0jb08j372262&site=xueshu_se&hitarticle=1. |

| 37. | He FH, Liu YZ, Wu Y, Gan YT. Clinical study of Huangqi Decoction in the treatment of senile functional constipation of Qi Deficiency Type. Zhongyaocai Zazhi. 2015;38:410-412. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 38. | He FH, Liu YZ, Wu Y, Gan YT. Clinical effect of Modified Shenqi Dihuang Decoction on chronic functional constipation in elderly with deficiency of Qi and Yin. Zhongguodangdai Yiyao Zazhi. 2019;26:173-177. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 39. | Hu SY, Zhong CL, Wang YX, Pan SQ. A multi-center clinical trial: Evaluation of Xiao'er Huashi Oral Liquid in treatment of functional constipation children (syndrome of internal heat stagnated from accumulated food). Zhongyi Erke Zazhi. 2018;41:2155-2159. |

| 40. | Huang CH, Lin JS, Li TC, Lee SC, Wang HP, Lue HC & Su YC. Comparison of a Chinese Herbal Medicine (CCH1) and Lactulose as First-Line Treatment of Constipation in Long-Term Care: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Double-Dummy, and Placebo-Controlled Trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:923190. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Hui YN. Clinical observation on the treatment of functional constipation in the elderly with the method of benefiting temperature and warming Yang. Guangming Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2018;33:678-780. |

| 42. | Jiang TY, Zhang QY. Clinical study of 36 cases of functional constipation by Strengthening the Spleen and Regulating the Lungs. Jiangsu Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2020;52:29-31. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 43. | Jiao CL, Zhang M, Gao YF. Clinical study of Danggui Aloe Capsule in the treatment of senile functional constipation. Xiandai Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2018;38:72-75. |

| 44. | Kong XR, Zhang HX. Self-designed Zhu-Yang Tongfu-tang in the treatment of 49 cases of senile functional constipation. Liaoning Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2020;47:105-107. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 45. | Lai YL, Liu Y, Shi HX, Zhang XH. An efficacy observation of Qi Zhu Jiang Ni Decoction for the treatment of senile functional constipation in 60 cases. Huanqiu Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2012;5:58-59. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 46. | Li JM. The old doctor of traditional Chinese medicine academic thought summarizing and using modified Buzhong Yiqi Decoction in treating qi deficiency and constipation clinical research. Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, 2012. Available from: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=56e5e812dfd206edb644ba2181553965&site=xueshu_se. |

| 47. | Li JJ, Ma Q, Liu BL, Liu MJ. Clinical observation on the treatment of functional constipation with Strengthening Pi and Nourishing Shen in 87 cases. Hebei Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2015;37:195-196. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 48. | Li W, Li QG, Wang S, Wang HB. Efficacy observation of Strengthening Pi and Smooth Bowel method for the treatment of senile functional constipation in 80 cases. Beijing Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2016;35:784-786. |

| 49. | Li Q, Rao WJ, Zeng SL. Clinical observation of Runchang Detoxification Ointment in the treatment of 60 cases of functional constipation. Hunan Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2019;35:16-18. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 50. | Lin ME, Liu YJ. Liuwei Anxiao Capsule treats senile functional constipation in 60 cases. Zhejiang ZhongyiyaoDaxue Xuebao. 2009;33:232-233. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 51. | Lin RJ. Multicenter clinical study of Baizhu Qiwu Granule in the treatment of slow transit constipation of colon. Hunan University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2012. Available from: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=3e20922f37623b2167f3cb27849edb33&site=xueshu_se. |

| 52. | Liu DB. Research on the treatment of chronic functional constipation of intestinal-qi-stagnation by the soothing liver and descending Qi. Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2013. Available from: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=ea2e63429ae52fed1679be3aa7db7f24&site=xueshu_se&hitarticle=1. |

| 53. | Liu LF, Study of the clinical observation and empirical on treating Qixu and Qizhi type Chronic Functional Constipation with Chaishao Sijun Jiawei Decoction. Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, 2017. Available from: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=f3c3f8a3c928b9925b4818f2189808a8&site=xueshu_se. |

| 54. | Liu YL, Cao YQ, Guo XT, Zhao XB. The clinical research into functional constipation treated with Qi-Boosting and Yin-Nourishing Decoction. Henan Zhongyi Zazhi. 2017;37:318-319. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 55. | Liu ZM, Chen AM, Zhong RH. Clinical observation of Jianpi Qingrun decoction in treating 146 Cases of infantile functional constipation with internal heat. Zhongyi Erke Zazhi. 2018;14:44-45. |

| 56. | Lv LY, He XW, Xu H, Wu PS. Clinical observation on 140 cases of functional constipation who were treated by modifying Jichuan Decoction. Sichuan Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2012;30:87-88. |

| 57. | LV N, Zhao YL, Wang M. Clinical study on Erhuang Decoction in the treatment of functional constipation. Anmo Yu Kangfuyixue Zazhi. 2018;9:51-52. |

| 58. | Mu Y, Chen Y, Cui H. Clinical Effect observation of Sini Decoction in the treatment of senile Functional constipation with Yang deficiency. Zhongyi LinchuangYanjiu Zazhi. 2019;11:112-113. |

| 59. | Qian HH, Shu TS, Zeng L, He WY. Study of Tongbian Granules in the treatment of chronic functional constipation. Nanjing ZhongyiyaoDaxue Xuebao. 2014;30:587-589. |

| 60. | Que RY, Fang HQ, Shen YT, Li Y. Study of clinical effect of Qilang decoction on functional constipation of qi and yin deficiency. Tianjin ZhongyiyaoDaxue Xuebao. 2018;35:182-185. |

| 61. | Ren AM. Clinical research on the lack of fluid and blood treatment with Runchang Pill disease of functional constipation. Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2014. Available from: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=a49bf586e3718aea1d64859b4789f9fd&site=xueshu_se. |

| 62. | Shao YF, Jiang XM. Self-designed Wenyang Xuanfei Prescription for the treatment of 50 cases of senile functional constipation with Yang deficiency. Fujian Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2019;50:79-81. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 63. | Su YS. Clinical Curative Effect observation on Functional constipation with Deficiency of Qi. Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, 2019. Available from: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=1020021871.nh&DbName=CMFD2020. |

| 64. | Sui N, Tian ZG. Observation of the colon delivers the function of treating chronic functional constipation by Zhu Yang Tong Bian Decoction. Liaoning Zhongyiyao Daxue Xuebao. 2012;14:174-176. |

| 65. | Sun SN, Wang CJ. Effect observation on patients with senile constipation treated by a decoction of increasing fluid promoting Qi adding or subtracting. Liaoning Zhongyiyao Daxue Xuebao. 2011;13:165-167. |

| 66. | Tao YY, Chen FL. Clinical observation of Jichuan Decoction and Buzhong Yiqi decoction in the treatment of kidney deficiency constipation. Jiating Yixue Zazhi. 2018;17:7. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 67. | Wang TT. Clinical Observation of Wenyang Tongfu Decoction in the treatment of functional constipation with spleen-kidney Yang Deficiency in the elderly. Shanxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2020. Available from: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=1020038553.nh&DbName=CMFD2020. |

| 68. | Wang QC. Er Bai decoction for the treatment of senile functional constipation in 46 cases. Shandong Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2004;23:696. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 69. | Wang HB, Zhang SS, Chen M, Wang ZM. Study on the advantages of regulating qi-flowing and strengthening Pi in treating functional constipation in the elderly. Beijing Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2011;30:770-773. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 70. | Wang XY, Qu LC. Lactulose for the treatment of functional constipation in senile adults. Anhui Yiyao Zazhi. 2013;17:485-486. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 71. | Wang Y, Luo JJ, Qiu JC, Chang K. The clinical curative effect of Tongbian Decoction in the treatment of children functional constipation in 60 cases (Shiji syndrome). Liaoning Zhongyi Zazhi. 2014;41:507-509. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 72. | Wang BC, Kang P. Clinical study on tongue particles treatment of chronic functional constipation with Yin deficiency and intestinal dryness syndrome. Zhongyiyao Daobao. 2015;30:1354-1356. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 73. | Wu SL, Zhou JB. Clinical observation of Nourishing Qi and Yin formulation for the treatment of senile functional constipation. Jiangsu Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2008;53:54-55. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 74. | Wu H. An efficacy observation of Zengye LunchangDecoction for the treatment of functional constipation in the Elderly (deficiency of Qi and Yin). Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, 2009. Available from: http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10199-2009208995.htm. |

| 75. | Wu GL. Clinical effect observation of the Yiqi Runchang Daozhi Decoction treating Qi and Yin Deficiency type constipation (slow transit). Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2013. Available from: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&dbname=CMFD201401&filename=1014116202.nh&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=95TEeoDIai8xJfasACAZf7rhnwAfIQRQ6Gbac2XmUH2fcDqOpqjZyWmtMHLO28WQ. |

| 76. | Wu JY, Wang QM, Zhang WX, Gao M. Clinical Observation of Modified Buzhong Yiqi Decoction in the Treatment of Functional Constipation. Zhongyiyao Daobao. 2013;41:114-115. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 77. | Xin H, Zhang JQ. Efficacy observation of modified ZengYi Chengqi decoction for the treatment of senile functional constipation. Sichuan Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2008;27:58-59. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 78. | Xin H, Wang XP. Runchang Tongbian Decoctionfor the treatment of senile functional constipation. Shanghai Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2014;48(02):43-44. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 79. | Xu GL, Miao CH, Xie XZ, Xie ZN. Exploration on effect of Sini decoction on 82 functional constipation patients. Shijie Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2013;8(09):1025-1027. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 80. | Xu L. The clinical study of Modified San Zi Chen Ping decoction treating functional constipation of phlegm dampness stagnation. Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2016. Available from: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&dbname=CMFD201701&filename=1016321605.nh&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=k1KwQUW2VuzO_MoxFcB3Pz5ACODPvUsX4aiN2TV-m566qr4iEciBInzV0zDl9rfv. |

| 81. | Xu YL, Yin HS, Liu LF, Wu L. Clinical observation on 40 Cases of chronic functional constipation in young and middle-aged women treated with Wenjing Decoction. Zhongguo ZhongxiyiJiehe Xiaohua Zazhi. 2018;26:794-796. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 82. |

Xu PC.

Clinical Effect observation of Yiqi Tongbian Prescription on functional constipation with deficiency of Qi. |

| 83. | Yan GL, Li L, Pu YP, Yang XD. Therapeutic Effect of Xuanshen Decoction on chronic functional constipation with deficiency of Qi and Yin. Sichuan Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2020;38:129-132. |

| 84. | Yan XY, Li Z, Yu Q, Lu Y. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three drugs in the treatment of chronic functional constipation in aged patients. Zhongguo XinyaoyuLinchuang Zazhi. 2013;32:154-157. |

| 85. | Yan LH. Clinical observation of Tongbian decoction in the treatment of Yin deficiency and intestinal dryness syndrome of slow transit constipation. Hunan University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2016. Available from: http://cdm d .cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10541-1016127057.htm. |

| 86. | Yang TZ. Clinical observation of the method of Zeng Shui Xing Zhou for the treatment of senile functional constipation in 64 cases. Zhongguo Laonianbingxue Zazhi. 2008;18:1025-1026. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 87. | Yang JM, Liu FD. Efficacy observation of Si Jun Zi Decoction for the treatment of functional constipation in the elderly. Shangxi Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2012;33:535-536. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 88. | Yang L, Yuan XX. Clinical observation of Jiu Long Capulase for the treatment of Functional Constipation. Zhongguo ZhongxiyiJiehe Xiaohua Zazhi. 2015;23:359-361. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 89. | Yao J, Sun XD, Yao H. Clinical observation of Ziyin Yangxue Decoction for the treatment of senile functional constipation (Jinkui Xueshao Syndrome). Beijing Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2016;35:689-691. |

| 90. | Ye ZZ, Lei X. Clinical observation of constipation prescription in treating chronic functional constipation. Beifang Yaoxue Zazhi. 2020;17:9-10. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 91. | Ye J, Shui DK, Liang QM, Liu Y. Clinical observation of modified Tongyou formulation for the treatment of senile functional constipation in different syndromes. Zhongguo ZhongxiyiJiehe Xiaohua Zazhi. 2016;24:387-389. |

| 92. | Yuan JY. Clinical observation on the treatment of functional constipation (deficiency of both qi and blood type) with Xumi Mixture. Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, 2016. Available from: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=4b58d0e77e5f6e2c60b470a052348fc7&site=xueshu_se&hitarticle=1. |

| 93. | Zeng WT. The clinical curative effect of Runtong decoction in the treatment of functional constipation with yin defiency. Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2017. Available from: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=11090dc6b8f89db1e650df313640e010&site=xueshu_se. |

| 94. | Zhan SS. Clinical study on Tongfukuanzhongtang combined with auricular point sticking treatment of functional constipation of spleen-qi stagnation. Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2016. Available from: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=26677bc2f05b8737248cc264291daad8&site=xueshu_se. |

| 95. | Zhang ZS. Clinical Observation on the Therapeutic Effect of Zhishui Shuanxiang Decoction on functional constipation with spleen-deficiency. Shanxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2020. Available from: http://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=1020038394.nh&DbName=CMFD2020. |

| 96. | Zhang B. The clinical study and mechanism discussion of Yiqi Wenyang Huayu method in the treatment of slow transit constipation. Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2014. Available from: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=d95fc14232785a1bdc20071a165ead81&site=xueshu_se&hitarticle=1. |

| 97. | Zhang Y, Fu R, Zhu LM, Zheng JG. Evaluation of treating senile functional constipation by Yishen Zengye Decoction adopting traditional Chinese medicine pattern effect study. Zhonghua Zhongyiyao Xuekan. 2014;32:2743-2746. |

| 98. | Zhang RZ, Yang G, Qian HH. Controlled clinical observation of Tongbian decoction in the treatment of constipation. Hubei Zhongyiyao Daxue Xuebao. 2014;16:80-82. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 99. | Zhang HL, Li ZB, Zhang HX, Guo YP. Therapeutic effect of Huazhuo Jiedu Tongbian decoction on senile functional constipation. Neimenggu Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2018;37:29-30. |

| 100. | Zhang YH, Yang JH. Clinical observation on regulating Qi-flowing to promote constipation method in the treatment of functional constipation. Guangming Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2018;33:501-503. |

| 101. | Zhang AM. Observation on the therapeutic effect of Shugan Lipi Runchang Decoction on functional constipation with the stagnation of liver and spleen. Shiyong Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2019;35:145. |

| 102. | Zhao JY, L Xuan. Clinical observation of Qinlong campuses for the treatment of constipation (Shire Syndrome). Zhongyaocai Zazhi. 2009;31:7-8. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 103. | Zhao J, Liu SG. Efficacy observation of Liu Mo Decoction for the treatment of functional constipation in 43 cases. Henan Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2014;34:900-901. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 104. | Zhao TX. Clinical observation in treating spleen-deficiency syndrome functional constipation with Yunchangruntong decoction. Gansu University of traditional Chinese medicine, 2015. Available from: http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10735-1015973469.htm. |

| 105. | Zhao JF. The curative effect observation of Jianertongbian power in treating spleen deficiency with hysteresis children constipation. Heilongjiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2015. Available from: http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10228-1015412758.htm. |

| 106. | Zhao ZY, Zhang N, Li AY. Effect of Xiaochaihu decoction on functional constipation complicated with depression. J Mod Med Health. 2018;34:2213-2215. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 107. | Zhao CP, Wang MQ. Clinical study of Spleen-Invigorating and Kidney-tonifying Decoction in the Treatment of senile functional constipation. Hebei Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2019;34:33-35, 57. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 108. | Zhong LLD, Cheng CW, Kun W, Dai L, Hu DD, Ning ZW, Xiao HT, Lin CY, Zhao L, Huang T, Tian K, Chan KH, Lam TW, Chen XR, Wong CT, Li M, Lu AP, Wu J, & Bian ZX. Efficacy of MaZiRenWan, a Chinese Herbal Medicine, in Patients With Functional Constipation in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17: 1303-1310. e18. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Zhou F, Zhang Q, Zhang YA, Zhang AZ. Clinical effect of qi-tonifying and yin-nourishing prescription in the treatment of chronic functional constipation with deficiency of both Qi and Yin: an analysis of 40 cases. Hunan Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2018;34:5-7. |

| 110. | Cremonini F. Standardized herbal treatments on functional bowel disorders: moving from putative mechanisms of action to controlled clinical trials. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:893-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Xiao HT, Zhong L, Tsang SW, Lin ZS, Bian ZX. Traditional Chinese medicine formulas for irritable bowel syndrome: from ancient wisdoms to scientific understandings. Am J Chin Med. 2015;43:1-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Huang Z, Yang Y, Liu F, Li L. Development of a Computerized Adaptive Test for Quantifying Chinese Medicine Syndrome of Myasthenia Gravis on Basis of Multidimensional Item Response Theory. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021;2021:9915503. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 113. | Huang Z, Hou Z, Liu X, Liu F, Wu Y. Quantifying Liver Stagnation Spleen Deficiency Pattern for Diarrhea Predominate Irritable Bowel Syndromes Using Multidimensional Analysis Methods. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;2018:6467135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Heaton KW, Radvan J, Cripps H, Mountford RA, Braddon FE, Hughes AO. Defecation frequency and timing, and stool form in the general population: a prospective study. Gut. 1992;33:818-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 493] [Cited by in RCA: 492] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Saad RJ, Rao SS, Koch KL, Kuo B, Parkman HP, McCallum RW, Sitrin MD, Wilding GE, Semler JR, Chey WD. Do stool form and frequency correlate with whole-gut and colonic transit? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:403-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Nelson AD, Camilleri M, Chirapongsathorn S, Vijayvargiya P, Valentin N, Shin A, Erwin PJ, Wang Z, Murad MH. Comparison of efficacy of pharmacological treatments for chronic idiopathic constipation: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut. 2017;66:1611-1622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Hu PJ, Liu XG. Gastroenterology. People's Medical Publishing House, Beijing, 2008: 115. |