Published online May 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i13.4137

Peer-review started: June 9, 2021

First decision: September 1, 2021

Revised: September 12, 2021

Accepted: March 16, 2022

Article in press: March 16, 2022

Published online: May 6, 2022

Processing time: 324 Days and 14.1 Hours

Musculoskeletal involvement in primary large vessel vasculitis (LVV), including giant cell arteritis and Takayasu's arteritis (TAK), tends to be subacute. With the progression of arterial disease, patients may develop polyarthralgia and myalgias, mainly involving muscle stiffness, limb/jaw claudication, cold/swelling extremities, etc. Acute development of rhabdomyolysis in addition to aortic aneurysm is uncommon in LVV. Herein, we report a rare case of LVV with the first presentation of acute rhabdomyolysis.

A 70-year-old Asian woman suffering from long-term low back pain was hospitalized due to limb claudication, dark urine and an elevated creatine kinase (CK) level. After treatment with fluid resuscitation and antibiotics, the patient remained febrile. Her workup showed persistent elevated levels of inflammatory markers, and imaging studies revealed an aortic aneurysm. A decreasing CK was evidently combined with elevated inflammatory markers and negativity for anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies. LVV was suspected and confirmed by magnetic resonance angiography and positron emission tomography with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose/computed tomography. With a favourable response to immunosuppressive treatment, her symptoms resolved, and clinical remission was achieved one month later. However, after failing to follow the tapering schedule, the patient was readministered 25 mg/d prednisolone due to disease relapse. Follow-up examinations showed decreased inflammatory markers and substantial improvement in artery lesions after 6 mo of treatment. At the twelve-month follow-up, she was clinically stable and maintained on corticosteroid therapy.

An exceptional presentation of LVV with acute rhabdomyolysis is described in this case, which exhibited a good response to immunosuppressive therapy, suggesting consideration for a differential diagnosis when evaluating febrile patients with myalgia and elevated CK. Timely use of high-dose steroids until a diagnosis is established may yield a favourable outcome.

Core Tip: Musculoskeletal involvement in large vessel vasculitis (LVV) usually manifests as polyarthralgia and myalgias but without elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels. Herein, we report a rare case of LVV with the first presentation of acute rhabdomyolysis. With the use of magnetic resonance angiography and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography, LVV was properly diagnosed. Ultimately, the patient achieved a favourable outcome after timely and persistent use of glucocorticoids. We present a case to supply clues for unusual diagnoses of LVV for febrile patients with myalgia and elevated CK.

- Citation: Fu LJ, Hu SC, Zhang W, Ye LQ, Chen HB, Xiang XJ. Large vessel vasculitis with rare presentation of acute rhabdomyolysis: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(13): 4137-4144

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i13/4137.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i13.4137

Large vessel vasculitis (LVV) features inflammation of the aorta and its primary branches; giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK) constitute the two main variants[1-3]. Patients with LVV share nonspecific constitutional symptoms (e.g., malaise, fever, fatigue, weight loss). Musculoskeletal involvement tends to be subacute, and with the progression of arterial destruction, patients may develop polyarthralgia or myalgias, mainly muscle stiffness/aching, limb/jaw claudication, cold/swelling extremities, paresis, etc. It has been reported that approximately half of GCA patients will present with polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), usually with an increased C-reactive protein (CRP)/ erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and elevated serum concentrations of hepatic enzymes, especially alkaline phosphatase, can be found in some cases[4]. However, acute development of rhabdomyolysis as the primary finding is uncommon in LVV.

A 70-year-old female patient was admitted to our unit due to a three-year history of low back pain and one month of dark urine, accompanied by fatigue and fever.

Over the past three years, the patient presented with low back pain and discontinuously underwent therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs without significant improvement. After taking health care products for one month, the pain scale score increased, and the patient developed limb claudication and dark urine.

The patient suffered from hypertension and cerebral infarction one year prior and underwent treatment with Lipitor 20 mg once a day and aspirin 100 mg once a day.

The patient drank occasionally. She had no family history of disease.

The patient had a fever of 38.1 °C, and other vital signs were within the normal range. Pulse inequality, bruits and reduced blood pressure/pulses were not found.

The laboratory findings were as follows: total protein (58.3 g/L), serum albumin (ALB, 27.7 g/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT, 211.5 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST, 389.3 U/L), creatine kinase (CK, 11668 U/L), haemoglobin (Hb, 93 g/L), CRP (129.2 mg/L), ESR (100 mm/h), and procalcitonin (PCT, 0.55 µg/L). Antinuclear antibody (ANA), myeloperoxidase-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (MPO-ANCA), and proteinase-3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA) tests were negative.

Chest computed tomography showed bilateral hydrothorax. Brain magnetic resonance images showed mild focal stenosis of the cerebral artery. Carotid artery ultrasound revealed atherosclerotic plaque. Other findings, including electromyography and abdomen ultrasound, were not obviously abnormal.

After an initial diagnosis of rhabdomyolysis, the patient was prescribed fluid therapy and hepatoprotective agents. Although CK and hepatic enzymes decreased 10 d later, the patient continued to experience fatigue and developed fever, with the highest temperature reaching 38.1 °C despite administration of various antibiotic regimens. The results of the follow-up work-up were as follows: ALT 107 U/L, AST 31 U/L, CK 54 U/L, Hb 90 g/L, CRP 164 mg/L, and ESR 101 mm/h.

Vasculitis was suspected given her clinical signs and symptoms, especially fever of unknown origin, and isolated, elevated inflammatory markers and vascular imaging were ordered for further evaluation.

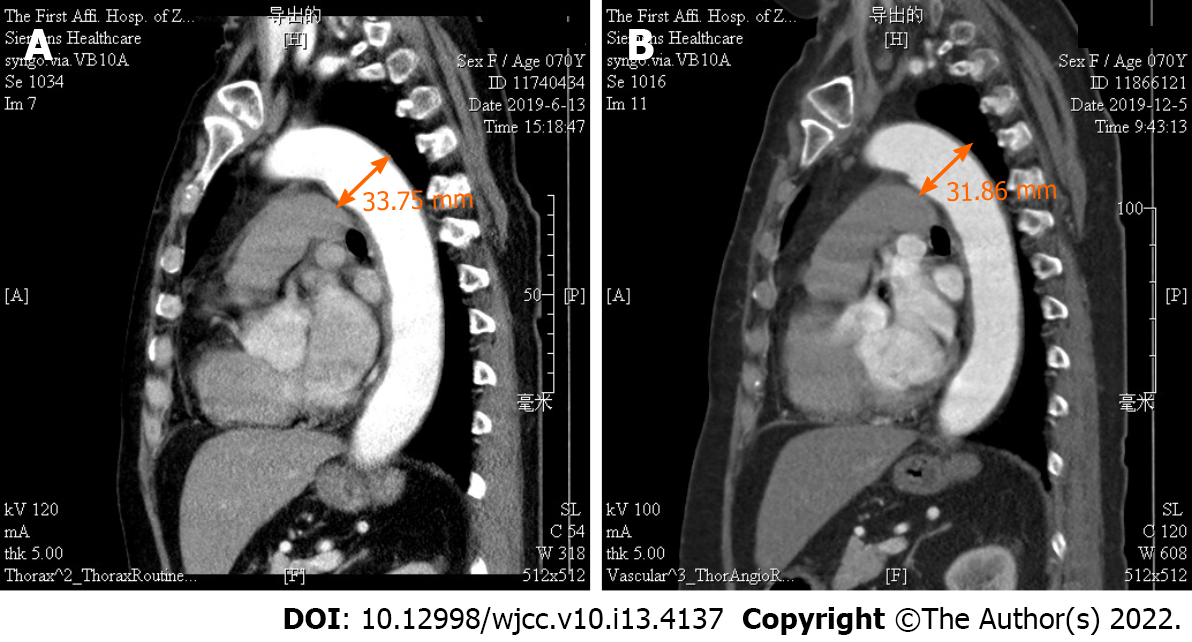

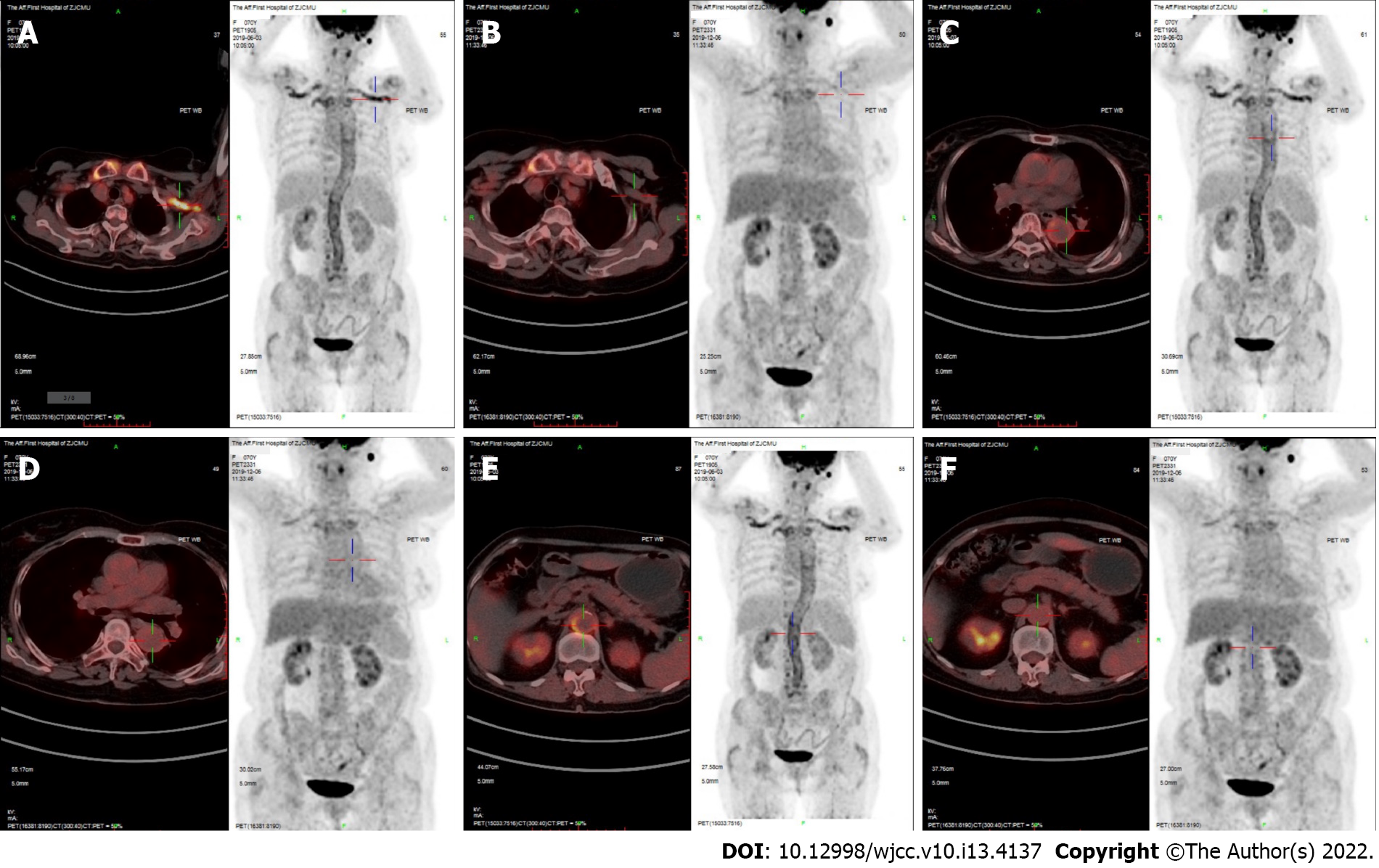

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) showed an aneurysm of the aortic arch (Figure 1). 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) revealed a thickened artery wall combined with increased FDG uptake in both the aorta and its major branches (Figure 2).

Based on the patient’s symptoms, especially the fever of unknown origin, laboratory investigations, typical thoracic aorta MRA and PET/CT images, she was diagnosed with LVV.

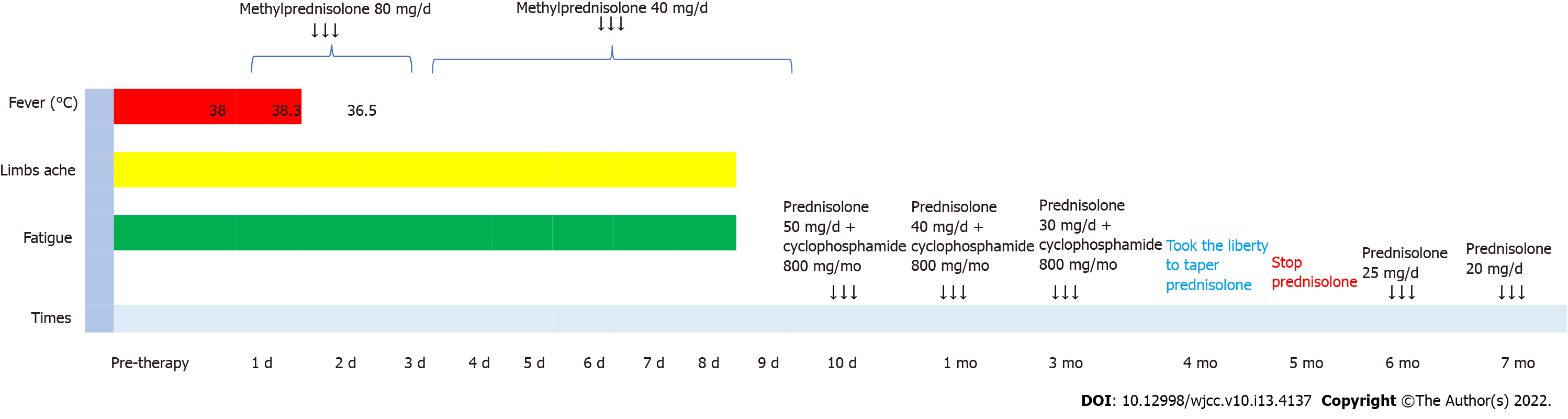

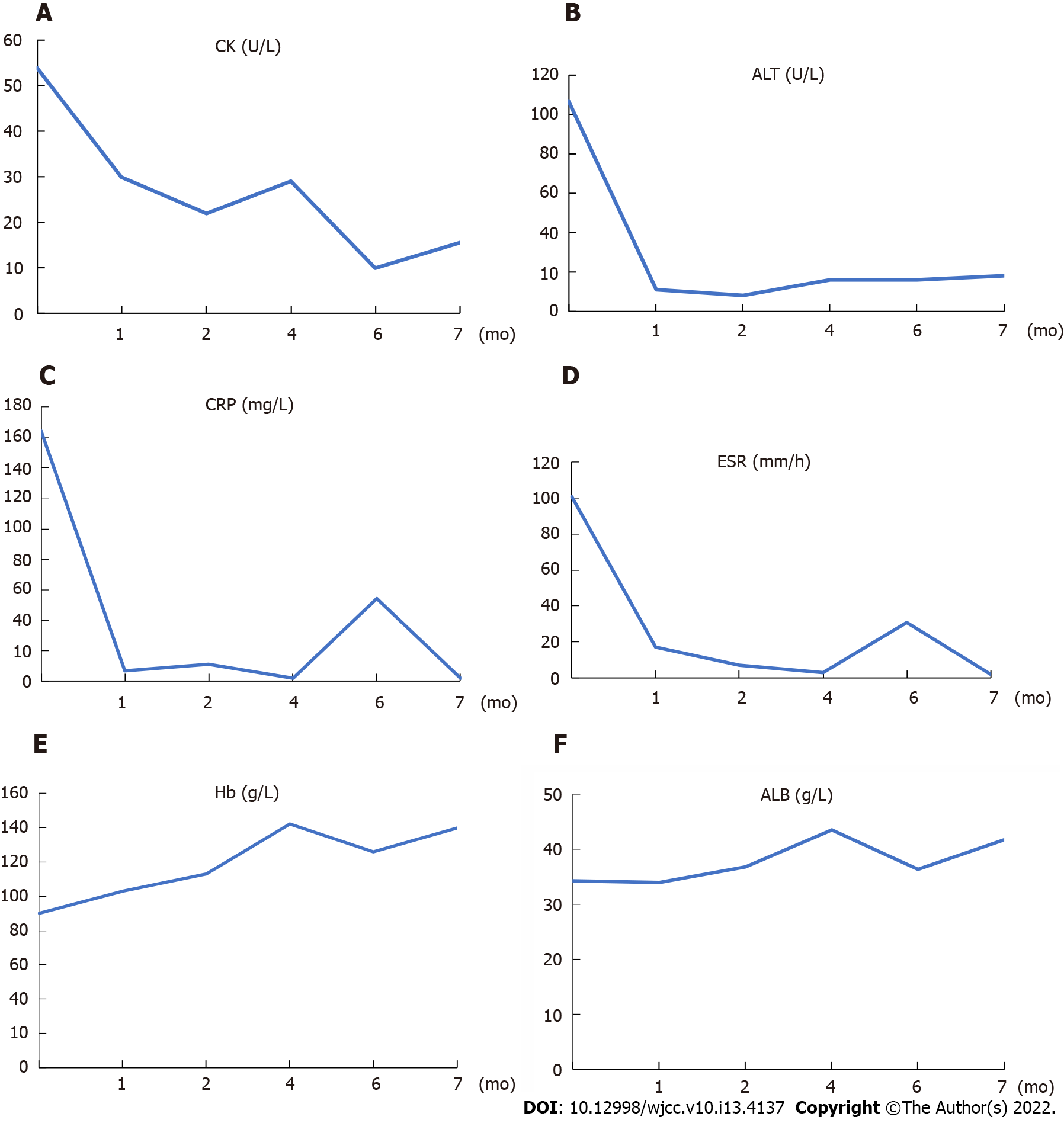

High-dose glucocorticoids (GCs) were started with methylprednisolone at 80 mg per day for 3 days and then tapered to 40 mg per day for 6 d. The clinical course describing the adjustment of GC is shown in Figure 3. The patient received oral prednisolone 50 mg/d on Day 10 after the initiation of immunosuppressive therapy and started to change to a tapering scheme. Additionally, one dose of intravenous pulse cyclophosphamide (800 mg) monthly was initiated. Clinical symptoms such as fever, fatigue and aching limbs resolved substantially after one week, and clinical remission was achieved one month later. The patient made an uneventful recovery and could walk normally after 3 mo of therapy. Laboratory tests for ALT, AST, CK, CRP and ESR remained at normal levels. The prednisolone was reduced to 30 mg/d 4 mo later.

However, the patient took the liberty of tapering and stopped the prednisolone at month 5, which led to an increase in inflammatory markers and was readmitted to our hospital with elevated CRP (54.14 mg/L) and ESR (31 mm/h) at month 6. Relapse was considered, and 25 mg/d prednisolone was prescribed. Related clinical markers improved one month later as follows: CRP from 54.14 to 2.1 mg/L, ESR from 31 to 2 mm/h, Hb from 126 to 140 g/L, and ALB from 36.4 to 41.8 g/L.

After six months of immunosuppressive treatment, follow-up thoracic aorta MRA demonstrated that the diameter of the aneurysm in the aortic arch had diminished from 33.75 to 31.86 mm (Figure 1). Furthermore, repeat 18F-FDG-PET/CT revealed that FDG uptake decreased prominently, indicating substantial improvement in arterial lesions (Figure 2). Clinical features corresponding to the course of immunosuppressive treatment are shown in Figure 4, except for month 5, when the patient failed to follow the tapering schedule; laboratory work-up showed a favourable response to the immunosuppressive regimen. At the twelve-month follow-up, the patient was clinically stable and maintained on corticosteroid therapy with 5 mg/d prednisolone.

The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)[5] has recommended that a suspected diagnosis of LVV should be confirmed by imaging or histology. High-dose GC therapy (40-60 mg/d prednisone equivalent) should be initiated immediately for the induction of remission in active GCA or TAK. EULAR also recommends adjunctive therapy with tocilizumab in refractory GCA. Imaging modalities are essential for diagnosing LVV, including MRA, CTA, CDU, etc.[6,7]. 18F-FDG-PET/CT is a popular diagnostic method that can detect LVV during the acute phase[8-10] and evaluate the response to therapy[11,12]. Immunosuppressive treatment is the first-line therapy for LVV, and GC should be tapered slowly and maintained for a long time, which is inevitably associated with the risk of major side effects[13,14]. Recently, biologic agents (tocilizumab, ustekinumab, abatacept, etc.) have been reported to be a novel therapy for severe and/or relapsing LVV[15,16].

There are currently no simple criteria for the diagnosis of LVV and its classification. GCA is categorized as granulomatous vasculitis of large- and medium-sized vessels, especially the temporal artery, and temporal artery biopsy (TAB) is the gold standard for diagnosing GCA[17,18]. However, imaging techniques have revealed a variable prevalence of extracranial involvement in GCA patients[19,20]. With the increasing use of whole-body imaging, more patterns of GCA have been described, including GCA with isolated increased inflammatory parameters and/or fever of unknown origin[8]. Compared with GCA, TAK affects younger people, and there is more angiographic evidence of narrowing or occlusion of the aorta[21-23].

In our case, the patient was older than 50 years, had an ESR ≥ 50 mm/h, and presented with claudication. Thoracic aorta MRA revealed an aneurysm of the aortic arch; furthermore, 18F-FDG-PET/CT revealed artery wall thickening along with increasing FDG metabolism in the aorta and its major branches. As TAB is not feasible in a live body, direct evidence of pathology was absent. The patient had previously experienced cerebral infarction, so headache may not be a manifestation of GCA. In this case, the patient had limb aches, which may be a manifestation of PMR. There is a close association between GCA and PMR[24,25]. While GCA is associated with prominent inflammation of the vessel wall with the inner layer and thoracic aneurysmal dilatation[26-28], TAK has predominant adventitial scarring and more frequent stenosis[21]; therefore, GCA was a more reasonable diagnosis for the patient. GCA treatment is dependent on GC use and requires a longer treatment duration[14]. Therefore, markers of inflammation, such as elevated ESR and CRP, returned when the patient stopped prednisolone abruptly.

Rhabdomyolysis is a clinical syndrome with causes including crush injuries, electrolyte disorders, infections, and the use of drugs such as statins[29,30]. Direct muscle injury remains the most common cause of rhabdomyolysis. LVV accompanied by rhabdomyolysis has not been reported before. However, rhabdomyolysis related to polyarteritis nodosa, a medium-sized vessel vasculitis, has been reported[31]. Hence, rhabdomyolysis related to LVV was reasonable. In addition, the patient had taken aspirin for a long time and had been administering health care products for one month, which could be another possible cause of the development of rhabdomyolysis. Whether rhabdomyolysis is directly linked to LVV is unknown and needs to be further verified.

LVV should be included as a differential diagnosis for febrile patients presenting with aches of the lips/Lower limb and elevated CK. Timely use of high-dose steroids until a diagnosis of LVV is established may yield a favourable outcome.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Rheumatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Anzola LK, Colombia S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Harky A, Fok M, Balmforth D, Bashir M. Pathogenesis of large vessel vasculitis: Implications for disease classification and future therapies. Vasc Med. 2019;24:79-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, Basu N, Cid MC, Ferrario F, Flores-Suarez LF, Gross WL, Guillevin L, Hagen EC, Hoffman GS, Jayne DR, Kallenberg CG, Lamprecht P, Langford CA, Luqmani RA, Mahr AD, Matteson EL, Merkel PA, Ozen S, Pusey CD, Rasmussen N, Rees AJ, Scott DG, Specks U, Stone JH, Takahashi K, Watts RA. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4416] [Cited by in RCA: 4244] [Article Influence: 353.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Smeeth L, Cook C, Hall AJ. Incidence of diagnosed polymyalgia rheumatica and temporal arteritis in the United Kingdom, 1990-2001. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1093-1098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dejaco C, Brouwer E, Mason JC, Buttgereit F, Matteson EL, Dasgupta B. Giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica: current challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13:578-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hellmich B, Agueda A, Monti S, Buttgereit F, de Boysson H, Brouwer E, Cassie R, Cid MC, Dasgupta B, Dejaco C, Hatemi G, Hollinger N, Mahr A, Mollan SP, Mukhtyar C, Ponte C, Salvarani C, Sivakumar R, Tian X, Tomasson G, Turesson C, Schmidt W, Villiger PM, Watts R, Young C, Luqmani RA. 2018 Update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of large vessel vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:19-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 774] [Cited by in RCA: 683] [Article Influence: 136.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hartlage GR, Palios J, Barron BJ, Stillman AE, Bossone E, Clements SD, Lerakis S. Multimodality imaging of aortitis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:605-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schäfer VS, Juche A, Ramiro S, Krause A, Schmidt WA. Ultrasound cut-off values for intima-media thickness of temporal, facial and axillary arteries in giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:1479-1483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hay B, Mariano-Goulart D, Bourdon A, Benkiran M, Vauchot F, De Verbizier D, Ben Bouallègue F. Diagnostic performance of 18F-FDG PET-CT for large vessel involvement assessment in patients with suspected giant cell arteritis and negative temporal artery biopsy. Ann Nucl Med. 2019;33:512-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rosenblum JS, Quinn KA, Rimland CA, Mehta NN, Ahlman MA, Grayson PC. Clinical Factors Associated with Time-Specific Distribution of 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose in Large-Vessel Vasculitis. Sci Rep. 2019;9:15180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nielsen BD, Gormsen LC. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose PET/Computed Tomography in the Diagnosis and Monitoring of Giant Cell Arteritis. PET Clin. 2020;15:135-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Quinn KA, Grayson PC. The Role of Vascular Imaging to Advance Clinical Care and Research in Large-Vessel Vasculitis. Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol. 2019;5:20-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee SW, Kim SJ, Seo Y, Jeong SY, Ahn BC, Lee J. F-18 FDG PET for assessment of disease activity of large vessel vasculitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019;26:59-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | de Boysson H, Liozon E, Ly KH, Dumont A, Delmas C, Aouba A. The different clinical patterns of giant cell arteritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37 Suppl 117:57-60. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Monti S, Águeda AF, Luqmani RA, Buttgereit F, Cid M, Dejaco C, Mahr A, Ponte C, Salvarani C, Schmidt W, Hellmich B. Systematic literature review informing the 2018 update of the EULAR recommendation for the management of large vessel vasculitis: focus on giant cell arteritis. RMD Open. 2019;5:e001003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Salvarani C, Hatemi G. Management of large-vessel vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2019;31:25-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ferfar Y, Mirault T, Desbois AC, Comarmond C, Messas E, Savey L, Domont F, Cacoub P, Saadoun D. Biotherapies in large vessel vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15:544-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Serling-Boyd N, Stone JH. Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of giant cell arteritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2020;32:201-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mahr A, Saba M, Kambouchner M, Polivka M, Baudrimont M, Brochériou I, Coste J, Guillevin L. Temporal artery biopsy for diagnosing giant cell arteritis: the longer, the better? Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:826-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Holm PW, Sandovici M, Slart RH, Glaudemans AW, Rutgers A, Brouwer E. Vessel involvement in giant cell arteritis: an imaging approach. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 2016;57:127-136. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Berger CT, Sommer G, Aschwanden M, Staub D, Rottenburger C, Daikeler T. The clinical benefit of imaging in the diagnosis and treatment of giant cell arteritis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2018;148:w14661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sanchez-Alvarez C, Mertz LE, Thomas CS, Cochuyt JJ, Abril A. Demographic, Clinical, and Radiologic Characteristics of a Cohort of Patients with Takayasu Arteritis. Am J Med. 2019;132:647-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | de Souza AW, de Carvalho JF. Diagnostic and classification criteria of Takayasu arteritis. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:79-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Arend WP, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Hunder GG, Calabrese LH, Edworthy SM, Fauci AS, Leavitt RY, Lie JT, Lightfoot RW Jr. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1129-1134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1389] [Cited by in RCA: 1447] [Article Influence: 41.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dejaco C, Matteson EL, Buttgereit F. [Diagnostics and treatment of polymyalgia rheumatica]. Z Rheumatol. 2016;75:687-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Camellino D, Matteson EL, Buttgereit F, Dejaco C. Monitoring and long-term management of giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16:481-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Keser G, Aksu K. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of large-vessel vasculitides. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39:169-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | de Boysson H, Daumas A, Vautier M, Parienti JJ, Liozon E, Lambert M, Samson M, Ebbo M, Dumont A, Sultan A, Bonnotte B, Manrique A, Bienvenu B, Saadoun D, Aouba A. Large-vessel involvement and aortic dilation in giant-cell arteritis. A multicenter study of 549 patients. Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17:391-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Muratore F, Kermani TA, Crowson CS, Koster MJ, Matteson EL, Salvarani C, Warrington KJ. Large-Vessel Dilatation in Giant Cell Arteritis: A Different Subset of Disease? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018;70:1406-1411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Coban YK. Rhabdomyolysis, compartment syndrome and thermal injury. World J Crit Care Med. 2014;3:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Ding LN, Wang Y, Tian J, Ye LF, Chen S, Wu SM, Shang WB. Primary hypoparathyroidism accompanied by rhabdomyolysis induced by infection: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:3111-3119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Iida H, Hanaoka H, Asari Y, Ishimori K, Kiyokawa T, Takakuwa Y, Yamasaki Y, Yamada H, Okazaki T, Doi M, Ozaki S. Rhabdomyolysis in a Patient with Polyarteritis Nodosa. Intern Med. 2018;57:101-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |