Published online Apr 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i11.3449

Peer-review started: November 10, 2021

First decision: January 11, 2022

Revised: January 25, 2022

Accepted: February 23, 2022

Article in press: February 23, 2022

Published online: April 16, 2022

Processing time: 149 Days and 6.5 Hours

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common public health issue that has been linked to cognitive dysfunction.

To investigate the relationship between COPD and a risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia.

A comprehensive literature search of the PubMed, Embase, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library electronic databases was conducted. Pooled odds ratios (OR) and mean differences (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using a random or fixed effects model. Studies that met the inclusion criteria were assessed for quality using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale.

Twenty-seven studies met all the inclusion criteria. Meta-analysis yielded a strong association between COPD and increased risk of MCI incidence (OR = 2.11, 95%CI: 1.32-3.38). It also revealed a borderline trend for an increased dementia risk in COPD patients (OR = 1.16, 95%CI: 0.98-1.37). Pooled hazard ratios (HR) using adjusted confounders also showed a higher incidence of MCI (HR = 1.22, 95%CI: -1.18 to -1.27) and dementia (HR = 1.32, 95%CI: -1.22 to -1.43) in COPD patients. A significant lower mini-mental state examination score in COPD patients was noted (MD = -1.68, 95%CI: -2.66 to -0.71).

Our findings revealed an elevated risk for the occurrence of MCI and dementia in COPD patients. Proper clinical management and attention are required to prevent and control MCI and dementia incidence in COPD patients.

Core Tip: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common public health issue that has been linked to cognitive dysfunction. The current meta-analysis was performed to investigate the relationship between COPD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia risk. Twenty-seven studies met all the inclusion criteria. Meta-analysis yielded a strong association between COPD and an increased risk of MCI incidence (odds ratio = 2.11, 95% confidence interval: 1.32-3.38). Our findings revealed an elevated risk for the occurrence of MCI and dementia in COPD patients. Proper clinical management and attention are required to prevent and control MCI and dementia incidence in COPD patients.

- Citation: Zhao LY, Zhou XL. Association of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with mild cognitive impairment and dementia risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(11): 3449-3460

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i11/3449.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i11.3449

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive multicomponent lung disease that occurs more commonly in the elderly[1]. It is characterised by a partially irreversible chronic obstruction of lung airflow resulting in an abnormal decrease in blood oxygen levels, potentially leading to cognitive dysfunction[2]. Various studies have estimated that the prevalence of cognitive impairment in COPD patients ranges from 16% to 57%[3,4]. A prior review of 17 individual studies by Yohannes et al[5] showed that 32% of COPD patients showed some signs of cognitive dysfunction, with no less than 25% of patients showing at least mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Cognitive impairment in COPD patients may compromise their capability to self-care and adhere to treatment regimens, making the relationship between COPD and cognitive impairment important for devising therapeutic approaches for COPD[6,7]. Some studies have focused on the relationship between COPD and neurologic function, but with inconsistent conclusions[8]. Data based on the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study showed that reduced lung function was associated with poor cognitive performance and higher risk of dementia hospitalization[9]. Data based on Taiwanese National Health Insurance Research Database showed that COPD patients exhibited a 1.27-fold higher risk of developing dementia[10].

To our knowledge, there has only been one published meta-analysis investigating the statistical association of COPD with cognition dysfunction. Zhang et al[11] concluded that COPD patients had an elevated risk of cognitive dysfunction. Similarly, only one single meta-analysis has looked at the relationship between COPD and dementia. Pooling data from three studies, Wang et al[12] showed that COPD patients faced a higher risk of developing dementia. However, these important clinical questions have not been investigated in a more thorough and conclusive manner. As such, we conducted a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the association between COPD and the risk of MCI and dementia.

Our meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines[13]. We conducted a comprehensive search using PubMed, Embase, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library online databases for articles published prior to March 31, 2021. The following key terms were used: “Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease” OR “COPD” OR “Chronic Obstructive Airway Disease” OR “COAD” AND “Mild Cognitive impairment” OR “MCI” OR “Cognitive dysfunction” OR “Cognitive decline” AND “Dementia”. Studies cited by articles that met the inclusion criteria were manually searched to identify additional eligible studies. Study eligibility was not restricted based on language, sex, or publication year. Systematic reviews, conference abstracts, and editorials were excluded due to insufficient data presentation details.

Inclusion criteria: We included studies that: (1) Investigated the association between COPD and a risk of MCI or dementia; (2) adopted a definite outcome of cognitive impairment or dementia in COPD and non-COPD subjects; (3) reported raw values necessary to calculate odds ratios (OR) or hazard ratios (HRs) for the incidence of cognitive impairment or dementia; (4) contained case controls, were prospective or retrospective-cohort, or had a cross-sectional design; and (5) compared the association between COPD and non-COPD patients.

Exclusion criteria: We excluded studies that: (1) Did not report relevant outcomes; or (2) were full-text inaccessible.

All eligible studies were separately screened by two reviewers to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. Screening was first conducted at the abstract content level, with relevant studies further investigated at the full-text level. Articles published in languages other than English were machine-translated using Google Translate, with the translated version reviewed. The following information was extracted from the included studies for summarization and analysis: Author, year, study design type, group investigated, sample size, diagnostic criteria for COPD, adjusted confounder for calculating pooled ratio, MCI prevalence, dementia prevalence, and scales used for cognitive assessment.

Study quality was assessed independently by two separate reviewers using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)[14], which examined three components: Selection, comparability, and ascertainment of outcome. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

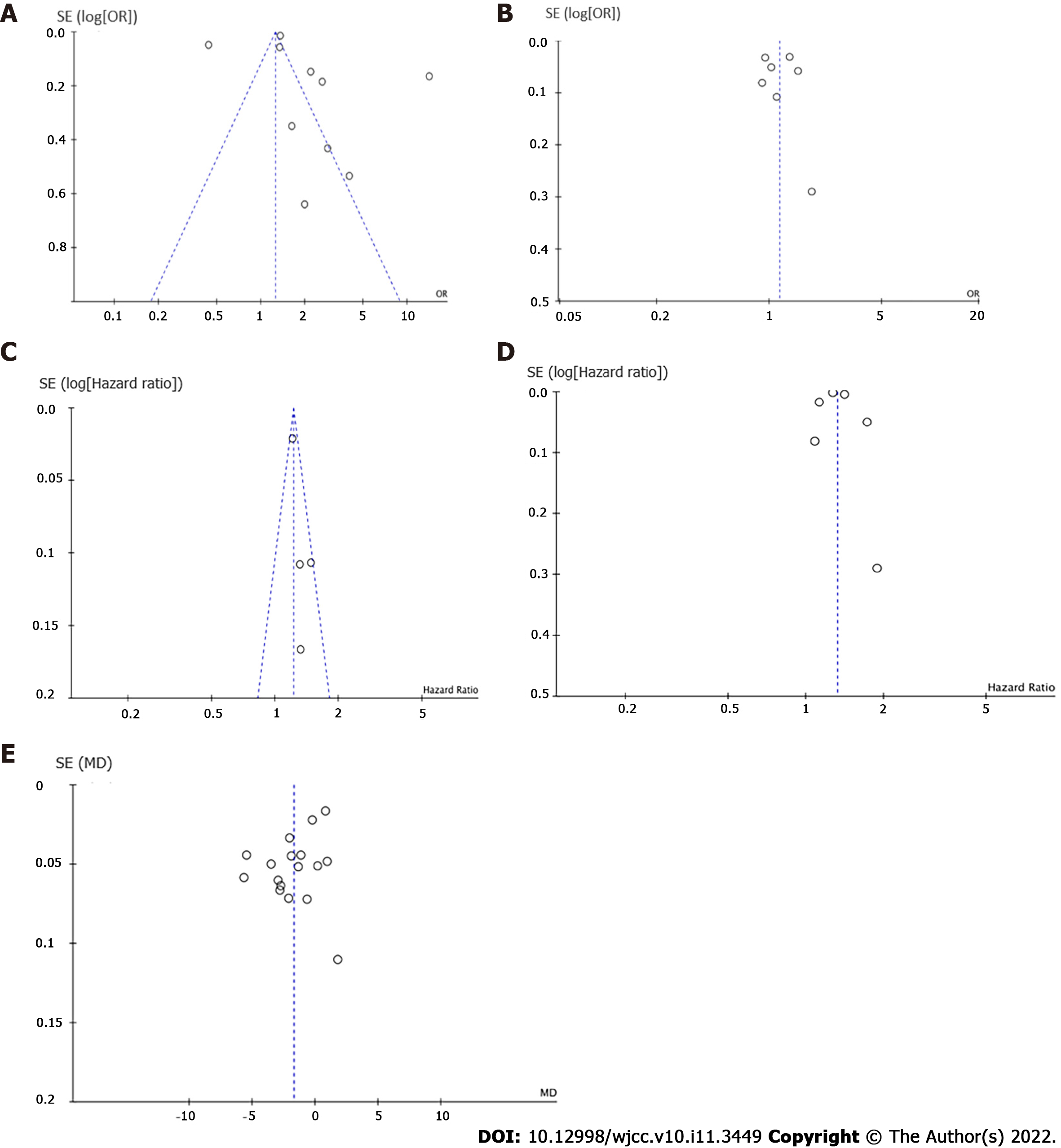

Publication bias was assessed using Funnel plot analysis and Egger’s regression test[15,16].

Mean differences (MDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for continuous outcomes. For categorical outcomes, ORs and HRs with 95%CIs were calculated to estimate pooled findings. Heterogeneity between studies (measurable heterogeneity) was evaluated using I2 statistics. If I2 values > 50%, a random-effects model was applied, otherwise a fixed-effect model was applied. Statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager software (Version 5.3, Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration 2014).

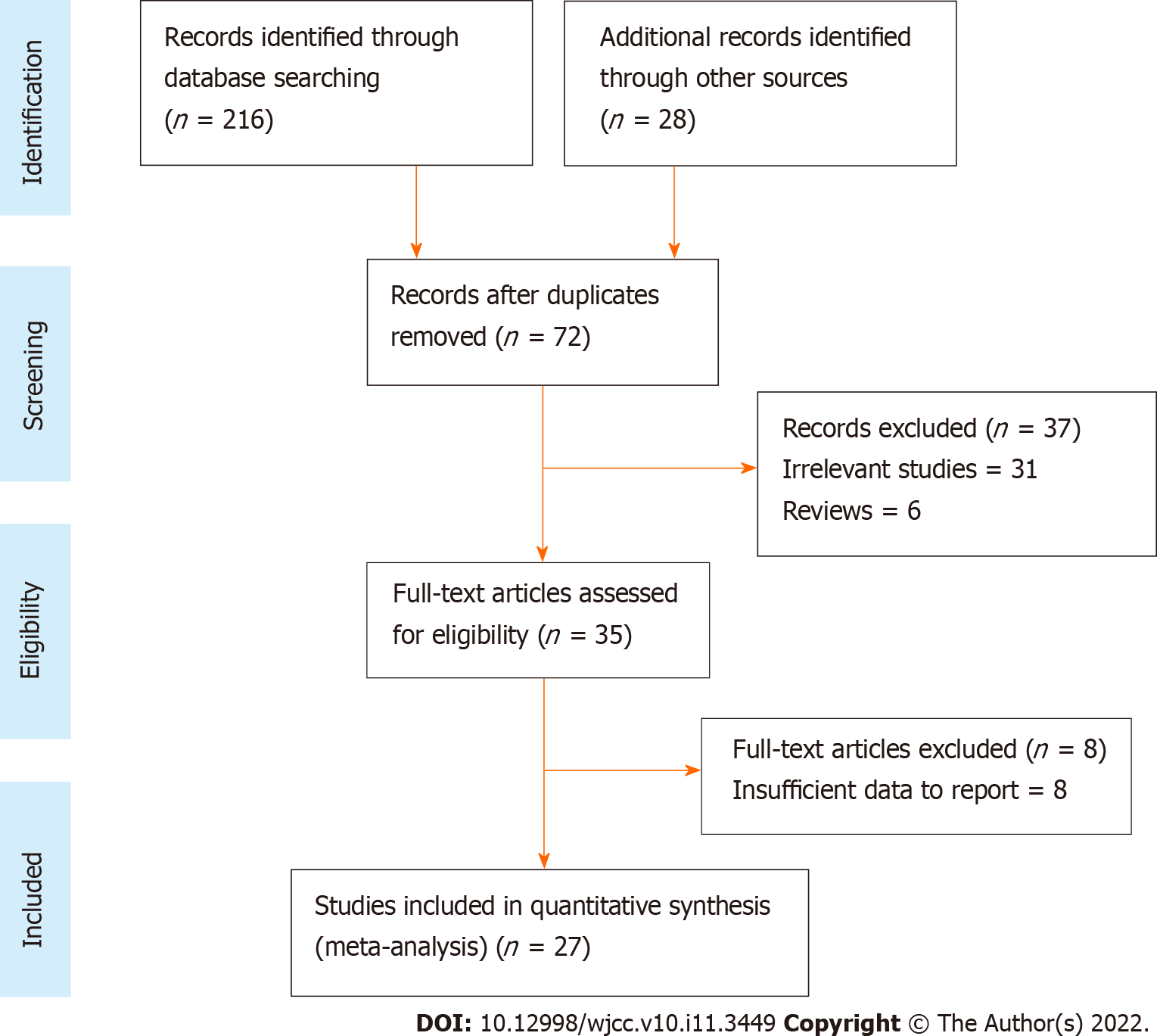

Preliminary screening of PubMed, Embase, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library databases yielded 234 results (Figure 1). Review of article title and abstract resulted in 72 remaining studies. Full-text review further excluded 45, leaving 27 studies[3,4,10,17-40] that were ultimately included in the meta-analysis.

Relevant study data, including the diagnostic criteria for COPD, sample size, and disease assessment scales for all the 27 included studies[3,4,10,17-40] are shown in Table 1. The included studies were published between 1996 and 2020, and study sample sizes ranged from 20 to 243420 subjects. Ten studies[17,19-22,28,29,34,35,39] were case-controlled, ten were cross-sectional[3,4,24-26,32,36-38,40], four were prospective-cohort[18,27,30,31], and three were retrospective-cohort[10,23,33]. Seventeen studies[4,17-22,25,31,32,34-40] reported cognitive impairment data based on the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) scoring system. Twenty-two studies used the GOLD criteria, three[10,23,33] reported the ICD-9 CM criteria, and two[3,26] followed the standardized guidelines for COPD diagnosis. The quality score was high in twelve studies, medium in seven, and low in six (Supplementary Table 1). The assessment criteria involving the NOS uses three broad criteria: Selection, comparability, and exposure, where the selection defines and analyses the cases and control subjects included in the study, comparability defines the matching or comparison of cases and control subjects for better empirical investigation, and exposure determines whether the study was conducted in a blinded or unbiased manner along with the response of the subjects.

| No. | Ref. | Country or region | Study design | Groups investigated | Age | Diagnostic criteria | Assessment scales | Adjusted variables | MCI (%) | Dementia (%) | NOS quality score |

| 1 | Mermit Çilingir et al[17], 2020 | Turkey | Case Control | COPD-E (n = 30); COPD-S (n = 54); Control (n = 37) | COPD-E-71.8 ± 12.3; COPD-S- 62 ± 10.2; Control-65.9 ± 12.8 | GOLD | MMSE; RCS | NA | NA | NA | 7 |

| 2 | Xie et al[18], 2019 | China | Prospective Cohort | COPD (n = 515); No COPD (n = 4220) | COPD-82.9 ± 9.7 | GOLD | MMSE | Age, gender, marital status, education level, alcohol drinking, current exercise, BMI, baseline prevalence of HTN, DM, and stroke | 18.8; 14.6 | 2.9; 1.6 | 8 |

| 3 | Samareh Fekri et al[19], 2017 | Iran | Case Control | COPD (n = 87); Control (n = 60) | COPD-60.4 ± 9.8; Control-58.1 ± 9.8 | GOLD | MMSE | Age and sex | 51.7; 36.6 | NA | 7 |

| 4 | Gupta et al[20], 2013 | India | Case Control | COPD-(n = 40); Control (n = 40) | COPD-57.2 ± 9.1; Control-56.9 ± 9.2 | GOLD | MMSE | Age | NA | NA | 5 |

| 5 | Li et al[21], 2013 | China | Case Control | Mild COPD-(n = 27); Severe COPD-(n = 35); Control (n = 27) | Mild COPD-70.4 ± 7.7; Severe COPD-68.2 ± 7.8; Control-66.2 ± 7.1 | GOLD | MMSE | Age, sex, education level, BMI, smoking status, and CVD | NA | NA | 6 |

| 6 | Li et al[22], 2013 | China | Case Control | Mild COPD-(n = 37); Severe COPD-(n = 48); Control (n = 37) | Mild COPD-69.2 ± 8.1; Severe COPD-67.6 ± 7.6; Control-66.5 ± 6.9 | GOLD | MMSE | Age, sex, education level, BMI, smoking status, and CVD | NA | NA | 8 |

| 7 | Liao et al[23], 2015 | Taiwan | Retrospective Cohort | COPD (n = 20492); No COPD (n = 40765) | COPD-68.2 ± 12.4; No COPD-67 ± 12.5 | ICD-9CM | NA | Age and sex | NA | 13.29.11 | 7 |

| 8 | Martinez et al[24], 2014 | Michigan | Cross-sectional | COPD (n = 1812); No COPD (n = 15723) | COPD-70.3 ± 9.0; No COPD-68.7 ± 9.9 | GOLD | ADL | Baseline cognition | 16.5; 12.4 | 3.9; 3.1 | 8 |

| 9 | Dal Negro et al[25], 2015 | Italy | Cross-sectional | COPD with LTOT (n = 73); COPD without LTOT (n = 73) | COPD with LTOT-70.9 ± 8.9; No COPD with LTOT-71.2 ± 9.1 | GOLD | MMSEMRC; CAT | Age, gender, smoking history, BMI, dyspnoea score, ABG, and lung function | 32.8 | NA | 6 |

| 10 | Singh et al[26], 2013 | United States | Cross-sectional | COPD (n = 288); No COPD (n = 1639) | MCI-82.7 ± 11.2; Normal Cognition-79.7 ± 12.5 | Standard criteria | BDI; CDR | BDI-II Depression, history of stroke, APOEe4 genotype, DM, HTN, CAD, and BMI | 14.6; 27.1 | NA | 7 |

| 11 | Singh et al[3], 2014 | United States | Cross-sectional | Total COPD (n = 1425); COPD (n = 171); No COPD (n = 1254) | COPD-80.8 ± 7.5; No COPD-79.1 ± 7.5 | Standard criteria | BDI | BDI-II depression, history of stroke, APOEe4 genotype, smoking, DM, HTN, CAD, z-scores, and BMI | NA | NA | 7 |

| 12 | Lutsey et al[27], 2019 | United States | Prospective Cohort | COPD (n = 2490); No COPD (n = 6108) | COPD-55.1 ± 5.8; No COPD-53.9 ± 5.7 | GOLD | NA | Age, sex, education level, race, center, cigarette smoking and pack-years of smoking, physical activity, BMI, systolic BP, BP medication use, diabetes, HDL, LDL lipid-lowering medications, CAD, heart failure, stroke, apolipoprotein E genotype, and fibrinogen | NA | NA | 6 |

| 13 | Siraj et al[28], 2020 | United Kingdom | Case Control | COPD (n = 64397); No COPD (n = 243420) | COPD-66.4 ± 10.9; No COPD-65.7 ± 11 | Standard criteria | NA | Age, sex, GP, BMI, smoking status, modified CCI, CV disease, corticosteroid use, and socioeconomic class | NA | NA | 7 |

| 14 | Villeneuve et al[29], 2012 | Canada | Case Control | Total COPD (n = 45); Control (n = 50) | COPD-68.4 ± 8.7; Control-67.4 ± 8.7 | GOLD | MMSE; MoCA | Age and education | 36.0; 12.0 | NA | 5 |

| 15 | Yeh et al[30], 2018 | Taiwan | Prospective Cohort | COPD (n = 10260); No COPD (n = 20513) | COPD-65.6 ± 11.8; No COPD-65.5 ± 11.9 | GOLD | NA | Age, sex, each comorbidity, inhaled corticosteroid, and oral steroids | NA | 11.1; 8.81 | 4 |

| 16 | Ozge et al[31], 2006 | Turkey | Prospective cohort | COPD (n = 54); Control (n = 24) | COPD-64.6 ± 8.5; Control-62.4 ± 8.4 | GOLD | MMSE,BDS, CDR, IADL | Age and sex | NA | NA | 6 |

| 17 | Favalli et al[32], 2008 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | COPD (n = 21); Control (n = 20) | COPD-74.6 ± 5.4; Control-73.7 ± 4.5 | GOLD | MMSE; GDS | NA | NA | NA | 5 |

| 18 | Liao et al[10], 2015 | Taiwan | Retrospective Cohort | COPD (n = 8640); No COPD (n = 17280) | COPD-68.7 ± 10.7; No COPD-68.7 ± 10.7 | ICD-9CM | Self-administered questionnaire | Age and sex | NA | 5.22; 7.06 | 6 |

| 19 | Thakur et al[33], 2010 | United States | Retrospective Cohort | COPD (n = 1202); Control (n = 302) | COPD-58.2 ± 6.2; Control-58.5 ± 6.2 | ICD-9CM | MRC; BODE index; MMSE | Age, sex, race, educational attainment, and smoking history | 5.5; 2.0 | NA | 7 |

| 20 | Zhou et al[34], 2012 | China | Case Control | COPD (n = 110); Control (n = 110) | COPD-80.9 ± 1.7; Control-80.8 ± 1.5 | GOLD | CDR; MMSE | Age and education | NA | NA | 6 |

| 21 | Dodd et al[4], 2013 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | COPD-E (n = 30); COPD-S (n = 50); Control (n = 30) | COPD-E-70 ± 11; COPD-S-69 ± 8; Control-65 ± 8 | GOLD | MMSE | Age | NA | NA | 7 |

| 22 | Isoaho et al[35], 1996 | Finland | Case Control | COPD (n = 81); Control (n = 245) | COPD-70.4 ± 4.8; Control-71.3 ± 5.9 | GOLD | MMSE | Age and sex | 17.0; 13.0 | 7.1; 3.2 | 6 |

| 23 | Lima et al[36], 2007 | Brazil | Cross-sectional | COPD (n = 30); Control (n = 34) | COPD-65 ± 8; Control-66 ± 8 | GOLD | MMSE; DSM-IV | NA | NA | NA | 5 |

| 24 | Ozyemisci-Taskiran et al[37], 2015 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | COPD-E (n = 133); COPD-S (n = 34); Control (n = 34) | COPD-E-69.3 ± 8.9; COPD-S-67.5 ± 8.9; Control-68.3 ± 8.8 | GOLD | MMSE; HAD; BODE | Age and sex | 22.6 | NA | 6 |

| 25 | Salik et al[38], 2007 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | COPD (n = 32); Control (n = 26) | COPD-66.7 ± 2.5; Control-65.7 ± 7.3 | GOLD | MMSE; MCS | NA | NA | NA | 5 |

| 26 | Sarınç Ulaşlı et al[39], 2013 | Turkey | Case Control | COPD (n = 112); Control (n = 44) | COPD-65 ± 7.6; Control-64 ± 9 | GOLD | MMSE | Age and sex | NA | NA | 5 |

| 27 | Tomruk et al[40], 2015 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | COPD (n = 35); Control (n = 36) | COPD-62.9 ± 6.3; Control-60.8 ± 6.2 | GOLD | MMSE | Age | NA | NA | 4 |

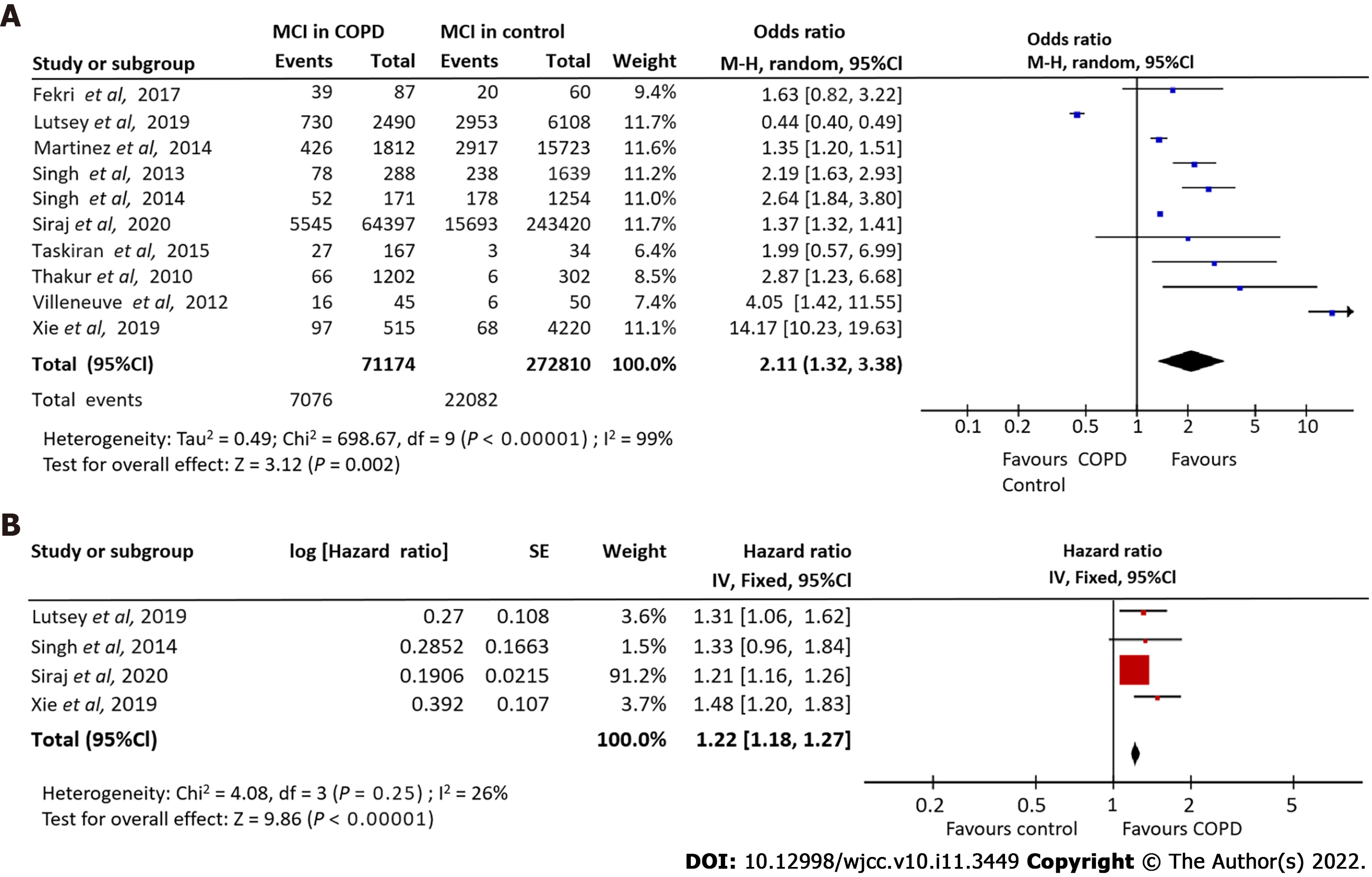

Ten studies[3,18,19,24,26-29,33,37] detailing 71174 COPD patients and 22082 control subjects investigated the association of COPD with MCI risk. Our meta-analysis indicated a strong association between COPD and an increased MCI incidence risk (OR = 2.11, 95%CI: 1.32-3.38). A significant degree of heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 99%). Using a random effects model, we demonstrated that COPD patients were 1.26 times more susceptible to MCI compared to non-COPD controls (Figure 2A).

Pooling adjusted HRs from four studies[3,18,27,28] investigating the relationship between COPD and MCI incidence revealed a significant association (HR = 1.22, 95%CI: -1.18 to -1.27; I2 = 26%] (Figure 2B).

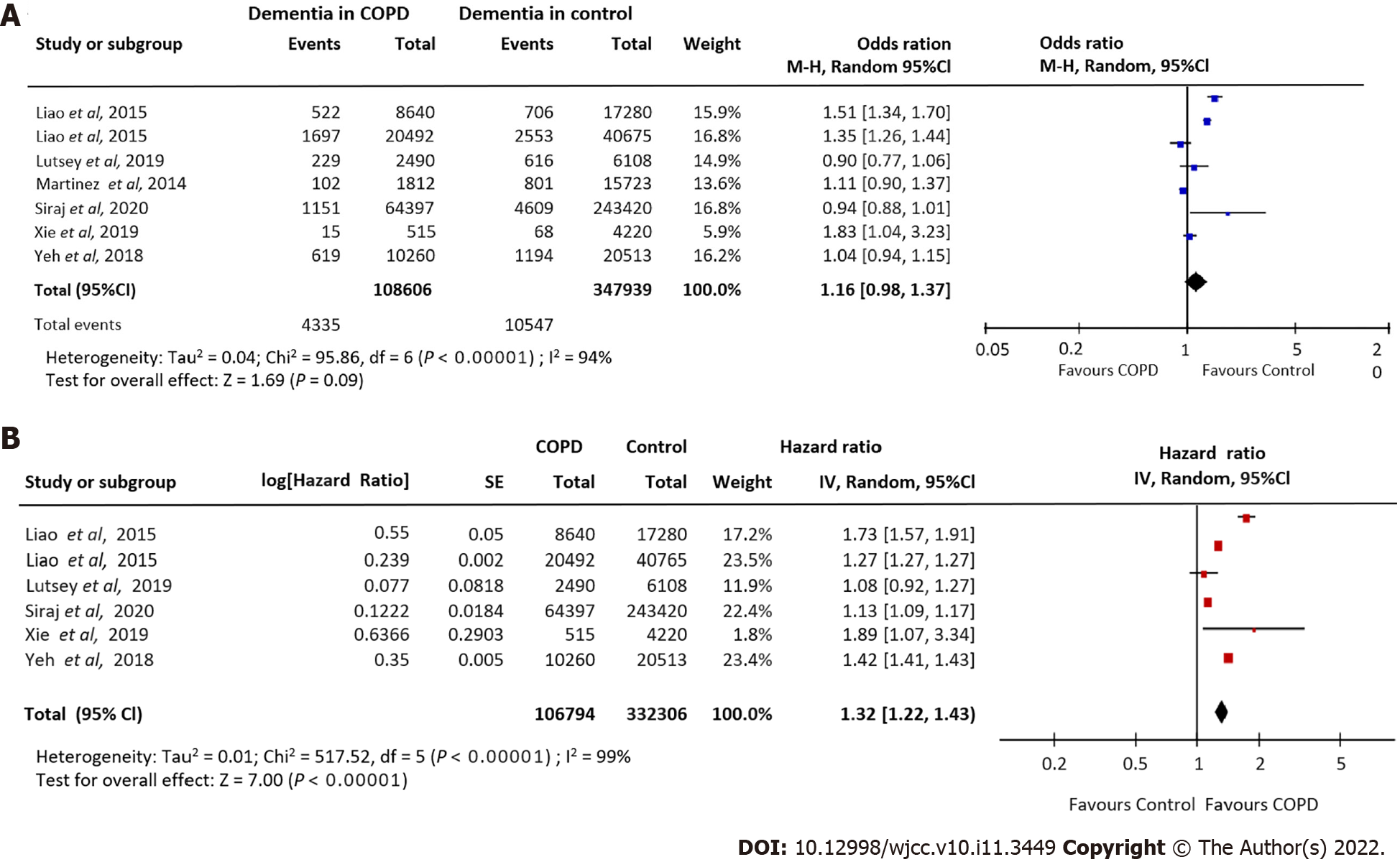

Seven studies[10,18,23,24,27,28,30] involving 108606 COPD patients and 347939 control subjects, investigated the relationship between COPD and dementia risk. Pooling these data showed a borderline trend for an increased dementia risk in COPD patients compared to non-COPD control patients (OR = 1.16, 95%CI: 0.98-1.37). A high degree of heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 94%). Our meta-analysis showed that COPD patients were more susceptible to dementia (Figure 3A).

Pooling adjusted HRs from six studies[10,18,23,27,28,30] investigating the relationship between COPD and dementia incidence revealed a significant association (HR = 1.32, 95%CI: -1.22 to -1.43; I2: 99%) (Figure 3B).

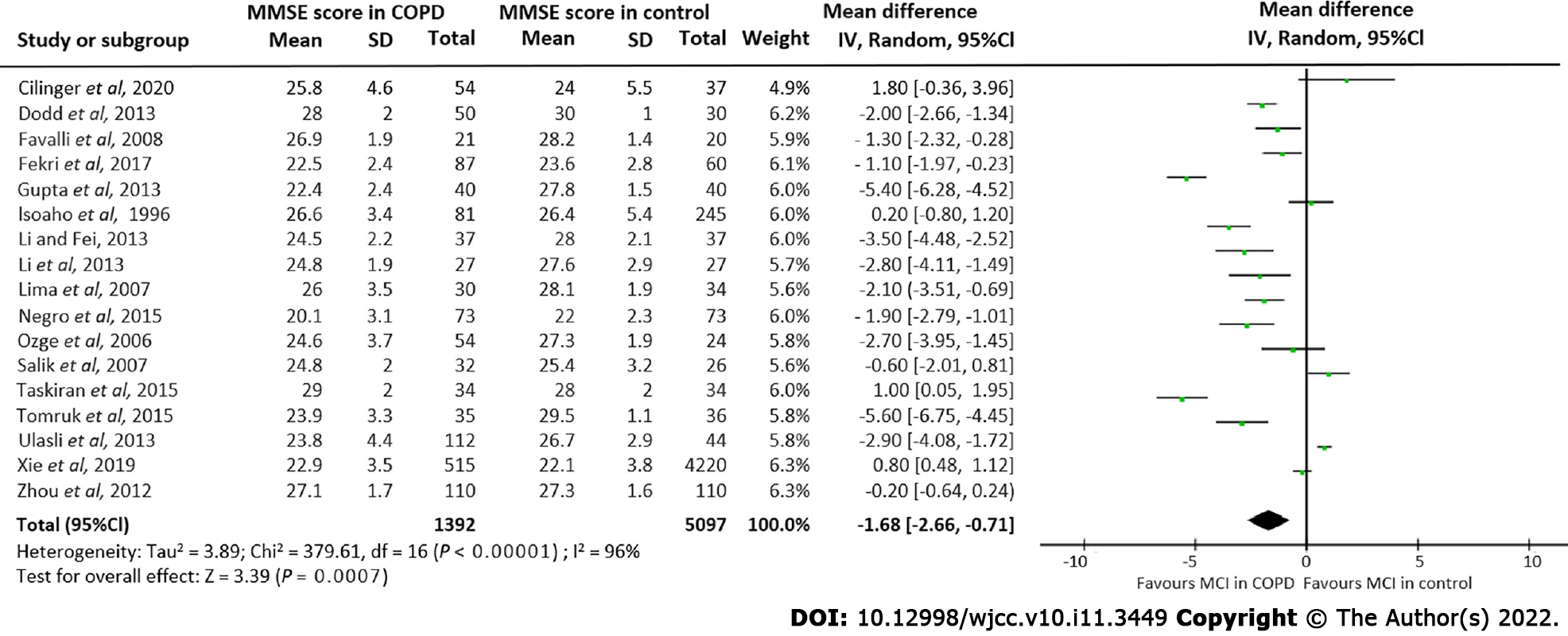

Seventeen studies[4,17-22,32,35-40,25,31,34] involving 1392 COPD patients and 5097 control subjects, reported mean MMSE score data for both COPD and non-COPD patients. Pooling these results showed a significant lower MMSE score in COPD patients compared to controls (MD = -1.68, 95%CI: -2.66 to -0.71] (Figure 4). A high degree of heterogeneity among these seventeen studies was observed (I2 = 96%).

Egger’s tests did not show any significant publication bias for the examined comparisons. Figure 5 shows the funnel plot of the studies included in each comparison. However, no significant publication biases were observed for the association of COPD with risk of MCI and dementia, MCI risk in COPD patients, dementia risk in COPD patients, and comparison of MMSE score between the COPD and control groups.

This study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis examining the association between COPD and the risk of MCI and dementia. We found that patients with COPD are 2.11 times more susceptible to MCI and 1.16 times more susceptible to dementia. Moreover, lower MMSE scores were observed in COPD patients, indicating greater cognitive impairment.

COPD-associated neurological impairment and dementia put a great burden on the patients and the healthcare system. In particular, declining cognition leads to COPD patients requiring more assistance for daily activities[41]. Our analysis was performed based on the reported adjustments within individual studies for confounding factors such as age, sex, smoking, body mass index, education level, diabetes mellitus, and previous history of stroke or cardiovascular disease[10,23,27,28,30]. Studies by Thakur et al[33], Singh et al[26], and Martinez et al[24] reported data as ORs for adjusted confounders and therefore were not included in the calculations for pooled incidence for MCI or dementia.

From a clinical approach, COPD can lead to pulmonary encephalopathy, hypoxemia, and inflammation, all of which may impact brain function[42]. Indeed, COPD patients exhibit a unique neurophysiological profile stemming from neurotoxicity featuring deficits of attention, motor, memory, and cognitive domain executive function[4]. Interestingly, the relationship between COPD and dementia persists even after accounting for the presence of vascular disease, suggesting that COPD is an independent predictor of dementia.

Our findings are consistent with the previous literature[5,11,12,42,43]. However, the available literature on the relationship between dementia and COPD remains limited, as only seven studies were found for this meta-analysis. Our study also had several other limitations. The included studies had different designs, which may be one of the leading causes of heterogeneity. Additional sources of heterogeneity may include different geographical population, variation in the diagnostic criteria of COPD, and diversity in the factors undertaken for the multivariate analysis of each included studies. The included studies also lacked long-term follow-up data, as well as data that would facilitate subgroup analysis based on co-morbidities, age, and gender. Finally, different studies varied on how they assessed and diagnosed COPD and cognitive impairment.

Our meta-analysis revealed an elevated risk for MCI and dementia in COPD patients. Proper clinical management and attention are necessary to prevent or mitigate the incidence of MCI and dementia in COPD patients.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common public health issue that has been linked to cognitive dysfunction. No clear evidence is available for the relationship between COPD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia risk.

To our knowledge, there has only been one published meta-analysis with limited number studies investigating the statistical association of COPD with cognition dysfunction.

The current meta-analysis was performed to investigate the relationship between COPD and MCI and dementia risk.

A comprehensive search was performed using PubMed, Embase, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library online databases for articles published prior to March 31, 2021.

Twenty-seven studies met all the inclusion criteria. Meta-analysis yielded a strong association between COPD and an increased risk of MCI incidence. It also revealed a borderline trend for an increased dementia risk in COPD patients. A significant lower MMSE score in COPD patients was noted.

Our findings revealed an elevated risk for the occurrence of MCI and dementia in COPD patients. Proper clinical management and attention are required to prevent and control MCI and dementia incidence in COPD patients.

Further large prospective observational studies are needed to strengthen the evidence on this important subject.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Biondi A, Byeon H S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Singh D, Agusti A, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, Celli BR, Criner GJ, Frith P, Halpin DMG, Han M, López Varela MV, Martinez F, Montes de Oca M, Papi A, Pavord ID, Roche N, Sin DD, Stockley R, Vestbo J, Wedzicha JA, Vogelmeier C. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: the GOLD science committee report 2019. Eur Respir J. 2019;53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 803] [Cited by in RCA: 1186] [Article Influence: 197.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ranzini L, Schiavi M, Pierobon A, Granata N, Giardini A. From Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) to Dementia in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Implications for Clinical Practice and Disease Management: A Mini-Review. Front Psychol. 2020;11:337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Singh B, Mielke MM, Parsaik AK, Cha RH, Roberts RO, Scanlon PD, Geda YE, Christianson TJ, Pankratz VS, Petersen RC. A prospective study of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the risk for mild cognitive impairment. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:581-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dodd JW, Charlton RA, van den Broek MD, Jones PW. Cognitive dysfunction in patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2013;144:119-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yohannes AM, Chen W, Moga AM, Leroi I, Connolly MJ. Cognitive Impairment in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Chronic Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:451.e1-451.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chang SS, Chen S, McAvay GJ, Tinetti ME. Effect of coexisting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cognitive impairment on health outcomes in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1839-1846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Campbell NL, Boustani MA, Skopelja EN, Gao S, Unverzagt FW, Murray MD. Medication adherence in older adults with cognitive impairment: a systematic evidence-based review. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10:165-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schou L, Østergaard B, Rasmussen LS, Rydahl-Hansen S, Phanareth K. Cognitive dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease--a systematic review. Respir Med. 2012;106:1071-1081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pathan SS, Gottesman RF, Mosley TH, Knopman DS, Sharrett AR, Alonso A. Association of lung function with cognitive decline and dementia: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:888-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liao WC, Lin CL, Chang SN, Tu CY, Kao CH. The association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and dementia: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22:334-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhang X, Cai X, Shi X, Zheng Z, Zhang A, Guo J, Fang Y. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease as a Risk Factor for Cognitive Dysfunction: A Meta-Analysis of Current Studies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52:101-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang Y, Li X, Wei B, Tung TH, Tao P, Chien CW. Association between Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Dementia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2019;9:250-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264-269, W64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21613] [Cited by in RCA: 18131] [Article Influence: 1133.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8858] [Cited by in RCA: 12571] [Article Influence: 838.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34245] [Cited by in RCA: 40366] [Article Influence: 1441.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088-1101. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Mermit Çilingir B, Günbatar H, Çilingir V. Cognitive dysfunction among patients in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Effects of exacerbation and long-term oxygen therapy. Clin Respir J. 2020;14:1137-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xie F, Xie L. COPD and the risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia: a cohort study based on the Chinese Longitudinal Health Longevity Survey. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:403-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Samareh Fekri M, Hashemi-Bajgani SM, Naghibzadeh-Tahami A, Arabnejad F. Cognitive Impairment among Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Compared to Normal Individuals. Tanaffos. 2017;16:34-39. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Gupta PP, Sood S, Atreja A, Agarwal D. A comparison of cognitive functions in non-hypoxemic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients and age-matched healthy volunteers using mini-mental state examination questionnaire and event-related potential, P300 analysis. Lung India. 2013;30:5-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Li J, Huang Y, Fei GH. The evaluation of cognitive impairment and relevant factors in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2013;85:98-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Li J, Fei GH. The unique alterations of hippocampus and cognitive impairment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2013;14:140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liao KM, Ho CH, Ko SC, Li CY. Increased Risk of Dementia in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Martinez CH, Richardson CR, Han MK, Cigolle CT. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cognitive impairment, and development of disability: the health and retirement study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:1362-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dal Negro RW, Bonadiman L, Bricolo FP, Tognella S, Turco P. Cognitive dysfunction in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with or without Long-Term Oxygen Therapy (LTOT). Multidiscip Respir Med. 2015;10:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Singh B, Parsaik AK, Mielke MM, Roberts RO, Scanlon PD, Geda YE, Pankratz VS, Christianson T, Yawn BP, Petersen RC. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and association with mild cognitive impairment: the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:1222-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lutsey PL, Chen N, Mirabelli MC, Lakshminarayan K, Knopman DS, Vossel KA, Gottesman RF, Mosley TH, Alonso A. Impaired Lung Function, Lung Disease, and Risk of Incident Dementia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:1385-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Siraj RA, McKeever TM, Gibson JE, Gordon AL, Bolton CE. Risk of incident dementia and cognitive impairment in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): A large UK population-based study. Respir Med. 2020;177:106288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Villeneuve S, Pepin V, Rahayel S, Bertrand JA, de Lorimier M, Rizk A, Desjardins C, Parenteau S, Beaucage F, Joncas S, Monchi O, Gagnon JF. Mild cognitive impairment in moderate to severe COPD: a preliminary study. Chest. 2012;142:1516-1523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yeh JJ, Wei YF, Lin CL, Hsu WH. Effect of the asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease syndrome on the stroke, Parkinson's disease, and dementia: a national cohort study. Oncotarget. 2018;9:12418-12431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ozge C, Ozge A, Unal O. Cognitive and functional deterioration in patients with severe COPD. Behav Neurol. 2006;17:121-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Favalli A, Miozzo A, Cossi S, Marengoni A. Differences in neuropsychological profile between healthy and COPD older persons. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:220-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Thakur N, Blanc PD, Julian LJ, Yelin EH, Katz PP, Sidney S, Iribarren C, Eisner MD. COPD and cognitive impairment: the role of hypoxemia and oxygen therapy. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:263-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zhou G, Liu J, Sun F, Xin X, Duan L, Zhu X, Shi Z. Association of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with cognitive decline in very elderly men. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2012;2:219-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Isoaho R, Puolijoki H, Huhti E, Laippala P, Kivelä SL. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cognitive impairment in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996;8:113-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lima OM, Oliveira-Souza Rd, Santos Oda R, Moraes PA, Sá LF, Nascimento OJ. Subclinical encephalopathy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2007;65:1154-1157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ozyemisci-Taskiran O, Bozkurt SO, Kokturk N, Karatas GK. Is there any association between cognitive status and functional capacity during exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Chron Respir Dis. 2015;12:247-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Salik Y, Ozalevli S, Cimrin AH. Cognitive function and its effects on the quality of life status in the patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;45:273-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sarınç Ulaşlı S, Oruç S, Günay E, Aktaş O, Akar O, Koyuncu T, Ünlü M. [Effects of COPD on cognitive functions: a case control study]. Tuberk Toraks. 2013;61:193-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | Soysal Tomruk M, Ozalevli S, Dizdar G, Narin S, Kilinc O. Determination of the relationship between cognitive function and hand dexterity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a cross-sectional study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2015;31:313-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 41. | Dulohery MM, Schroeder DR, Benzo RP. Cognitive function and living situation in COPD: is there a relationship with self-management and quality of life? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1883-1889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 42. | Baird C, Lovell J, Johnson M, Shiell K, Ibrahim JE. The impact of cognitive impairment on self-management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review. Respir Med. 2017;129:130-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 43. | van Beers M, Janssen DJA, Gosker HR, Schols AMWJ. Cognitive impairment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: disease burden, determinants and possible future interventions. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2018;12:1061-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |