Published online Jan 7, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i1.309

Peer-review started: July 1, 2021

First decision: September 28, 2021

Revised: November 9, 2021

Accepted: November 28, 2021

Article in press: November 28, 2021

Published online: January 7, 2022

Processing time: 182 Days and 4.2 Hours

Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is a rare but life-threatening disease in pregnant women. Anticoagulation is the first-line therapy for CVT management. However, some patients have poor outcomes despite anticoagulation. Currently, the endovascular treatment of CVT in pregnant women remains controversial. We report a rare case of CVT in a pregnant woman who was successfully treated with two stent retriever devices.

The patient was a 29-year-old pregnant woman. She was first diagnosed with hyperemesis gravidarum due to severe nausea and vomiting for one week. As the disease progressed, she developed acute left hemiplegia. Imaging confirmed the diagnosis of superior sagittal sinus, right transverse sinus and sinus sigmoideus thrombosis. As anticoagulant therapy was ineffective, she underwent thrombectomy. After the mechanical thrombectomy, her headache diminished. Three weeks later, the patient was completely independent. At a 3-mo follow-up, no relapse of symptoms was observed.

Mechanical thrombectomy may be an effective alternative therapy for CVT in pregnant women if anticoagulation therapy fails.

Core Tip: Pregnancy-related cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is an uncommon and severe disease. Endovascular treatment of CVT in pregnant women remains controversial. We report a rare case of CVT in a pregnant woman who was successfully treated with two stent retriever devices. Given its rare incidence and highly diverse clinical manifestations, the clinical diagnosis of CVT is challenging. In order to avoid misdiagnosis in these high-risk patients, prompt multidisciplinary diagnosis and treatment is essential.

- Citation: Zhou B, Huang SS, Huang C, Liu SY. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in pregnancy: A case report . World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(1): 309-315

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i1/309.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i1.309

Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is a rare and severe disease. A recent study found that approximately one-third of CVT patients did not return to paid work, and this was more common in women and patients with parenchymal lesions[1]. According to the 2017 European ESO/EAN Guidelines, anticoagulation is the main therapeutic regimen for CVT in clinical practice[2]. However, some patients have poor outcomes despite anticoagulation. Studies have demonstrated the benefits of endovascular therapy with respect to CVT recanalization[3]. However, due to the low-level of available evidence, the 2017 European guidelines do not make any recommendations, and specific analyses regarding pregnant populations are limited. Here, we report a rare case of CVT in a pregnant woman who underwent endovascular mechanical thrombectomy using two stent retriever devices.

A 29-year-old female in the 8th week of her first pregnancy presented to the Obstetrics Department of a referral hospital. The patient had nausea, vomiting and persistent headaches for one week prior to admission. Due to severe nausea and vomiting in pregnancy, she was first diagnosed with hyperemesis gravidarum.

A persistent headache with nausea and non-projectile vomiting occurred 1 wk previously. The headache was mainly characterized by mild-to-moderate, pulsatile headache on both sides of the temple, which was more obvious when shaking her head. The patient had no other discomfort such as fever, blurred vision, hemiplegia, consciousness disturbance, seizures, etc.

About 8 wk previously, the patient’s menstruation ceased. Two weeks ago, she was treated with oral progesterone to prevent miscarriage due to a small amount of intermittent vaginal discharge. She denied a history of hematologic disorders, autoimmune diseases, intracranial and extracranial tumors.

The patient denied taking oral contraceptives and denied a family history of hereditary thrombophilia.

On admission, the patient’s main symptoms were a persistent headache, nausea and vomiting. Her vital signs and muscle strength were normal. Three days after ad

Cerebrospinal fluid pressure was 220 mmH2O, cerebrospinal fluid cell count and protein were nearly normal, and β-human chorionic gonadotropin was 150073 IU/L. Her D-dimer level was 12.5 mg/L. Other laboratory tests were normal, such as routine blood tests, coagulation function, routine urinalysis, liver function, kidney function, homocysteine, protein C, protein S and so on. Due to an acute onset of neurologic symptoms, and objective findings upon neurologic examination, the most probable diagnosis was CVT.

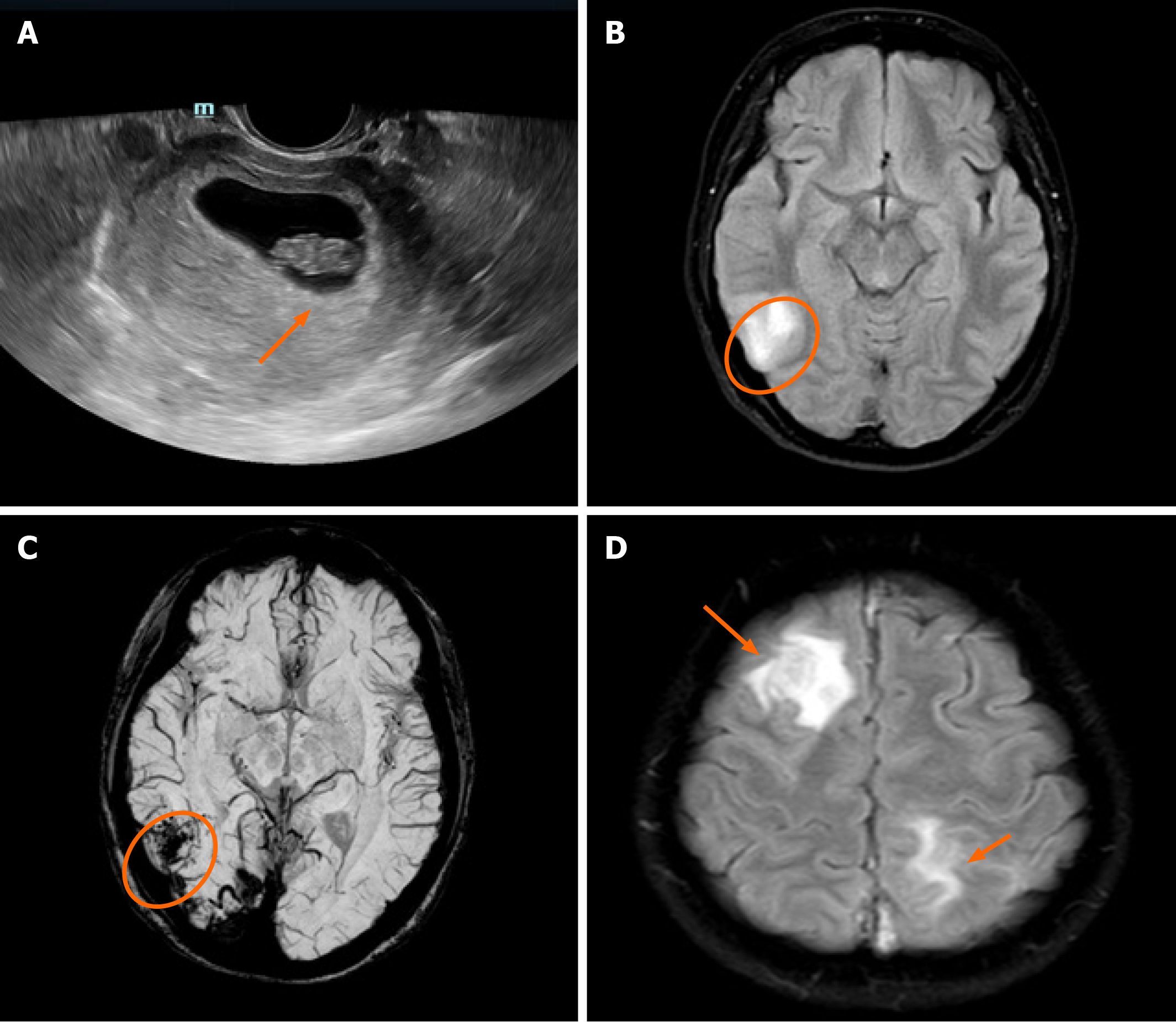

Ultrasound scan was performed, which showed a fetus at 8 wk of gestation (Figure 1A). Prethrombectomy brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) combined with magnetic resonance venography revealed superior sagittal sinus, right transverse sinus and sinus sigmoideus thrombosis with a right temporal lobe venous infarct (Figure 1B and C). Post-thrombectomy MRI revealed new lesions in the right frontal lobe and left parietal lobe (Figure 1D).

The patient was diagnosed with CVT.

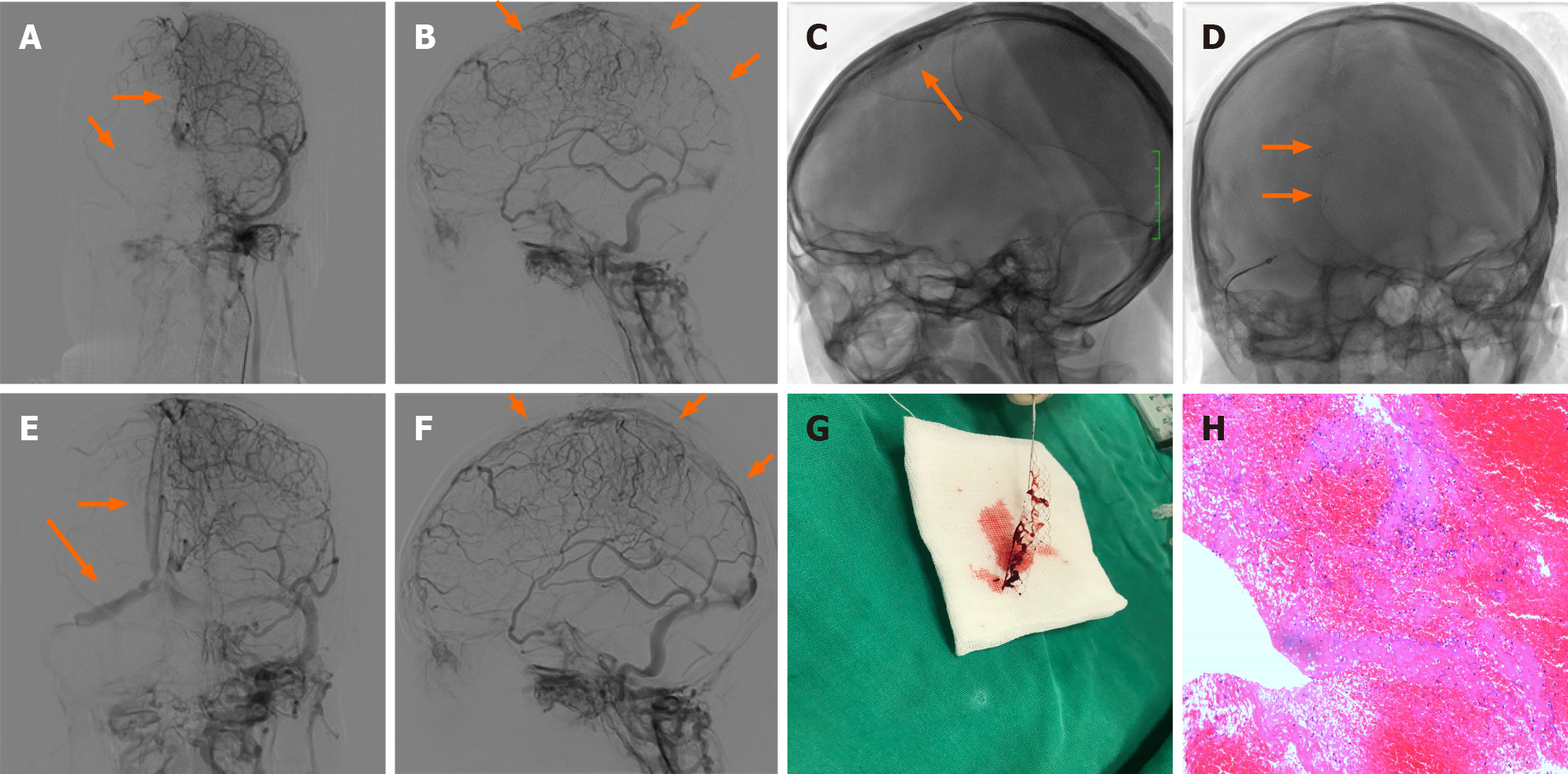

Anticoagulant treatment with subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) administered twice a day was initiated. However, 3 d after admission, her symptoms worsened. The patient developed a right-sided weakness (4/5), and a progressive left limb weakness (3/5). Subsequent MRI confirmed new lesions in the right frontal lobe and left parietal lobe. Selective catheterization of the right internal carotid artery confirmed occlusion of the superior sagittal sinus, as well as the right transverse sinus, and sinus sigmoideus (Figure 2A and B). Despite anticoagulation, the patient’s neurological condition declined; therefore, emergency mechanical thrombectomy was performed. She successfully attained occluded superior sagittal sinus recanalization, as well as right transverse sinus, and sinus sigmoideus recanalization (Figure 2C-G). Microscopic appearance of the cerebral embolus specimen was consistent with a mixed thrombus (Figure 2H). As there were some residual thromboses, she continued LMWH therapy on the first post-procedure day. Immediately after the procedure, her headache diminished.

Three weeks after the procedure, the patient was completely independent (modified Rankin Scale score = 0), and at a 3-mo follow-up, symptomatic relapse was not reported.

Primary headaches, such as tension headaches and migraines, frequently occur in pregnant women and are the most common causes of headaches[4]. However, if pregnant women experience new, deteriorating headaches or when the headaches change in character, secondary origins may exist[5]. Pregnancy is a risk factor for secondary headache disorders. Anesthesia for labor, hypercoagulability, as well as hormonal changes are factors for the high incidence of secondary headaches during pregnancy. The most frequent causes of secondary headaches include stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage, pituitary tumors, CVT, and reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome[4].

Pregnancy is an important risk factor for CVT. In pregnancy, CVT has a prevalence of 1.2 per 100000 deliveries[6]. An increase in prevalence within the 1st trimester is associated with women who have pre-existing thrombophilia who become pregnant. Given its rare incidence and highly diverse clinical manifestations, the clinical diagnosis of CVT is challenging. High incidences of headaches, motor weakness, seizures, and comatose/obtunded status have been reported, in tandem with clinical manifestations among non-pregnant/puerperal patients[7].

Due to its superior diagnostic accuracy, MRI is the most suitable option for diagnosing CVT in pregnant women, especially as it does not expose them to radiation, and it clearly differentiates soft tissues. Recent studies have shown that MRI performed with a 1.5-T magnet is safe for diagnosis in pregnant women at all trimesters[8].

Anticoagulation constitutes the first-line therapeutic option for managing the acute stage of CVT. LMWH has been confirmed to be preferable to unfractionated heparin, as it results in reduced mortality as well as better functional outcomes, with equivalent rates of systemic bleeding[9]. Furthermore, in special populations, such as pregnant women, LMWH cannot traverse the placenta, and adverse reactions associated with teratogenicity or fatal bleeding have not been reported. Therefore, it is a reasonable choice of anticoagulation therapy for CVT patients during pregnancy[10].

In the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis, approximately 13% of cases had poor outcomes even after anticoagulation treatment[7]. The 2017 European ESO/EAN Guidelines recommend that patients with acute CVT who are at a low risk of adverse consequences before treatment should not undergo endovascular treatment.

Currently, although there are no randomized controlled trials regarding the effectiveness and safety of endovascular treatment for CVT, more and more evidence has shown that mechanical thrombectomy is a safe and effective treatment for CVT[3,11]. A 2017 review of 235 patients with CVT and a neurologic presentation described the effectiveness and safety of endovascular treatment for CVT. They found that although 40.2% of patients presented with poor baseline characteristics (encephalopathy or coma), 69.0% of patients achieved complete radiographic resolution of CVT after endovascular treatment, 76% of patients achieved a good clinical outcome (a modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2), and the rate of worsening or new intracranial hemorrhage was only 8.7%.

However, studies on the efficacy and safety of mechanical thrombectomy for CVT in pregnant women are mainly limited to case reports and small series. To date, there are only 12 case reports of mechanical thrombectomy for the treatment of CVT in pregnant women. Table 1 summarizes the reported cases of CVT in pregnant women treated with mechanical thrombectomy from the literature along with our patient[12-19]. In addition to pregnancy, most patients (7/12) have other risk factors, such as antithrombin III deficiency and so on. Because of consciousness disorder or rapid deterioration of neurological function, all the patients underwent thrombectomy with or without thrombolysis. In two patients, thrombectomy resulted in complete restoration of flow (2/8) and in the remaining 6 patients (6/8) partial restoration of flow was achieved. Following thrombectomy, two (2/12) patients experienced non-fatal intracranial hemorrhage, 9 (75%) patients had a good clinical outcome and one patient died.

| Ref. | Age | Risk factors | Treatment | Results of post-intervention CTA/DSA | Maternal outcome | Fetal outcome | Complications |

| Kourtopoulos et al[12], 1994 | 18 | Pregnancy | Open thrombectomy, thrombolysis, heparin + actilyse | NA | mRS = 5 after 3 mo | Healthy | Intracranial hemorrhage |

| Chow et al[13], 2000 | 21 | Pregnancy, anti-phospholipid antibodies | Heparin, rheolytic thrombectomy, urokinase | Partial restoration of flow | mRS = 0 after 6 mo | NA | None |

| Ou et al[14], 2003 | 29 | Pregnancy, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome | Local thrombolysis (urokinase), mechanical thrombectomy, LMWH | Partial restoration of flow | mRS = 2 at discharge | Healthy | None |

| Falavigna et al[15], 2006 | 24 | Pregnancy | Mechanical lysis + abciximab | Complete restoration of flow | mRS = 0 after 12 mo | Healthy | Intracranial hemorrhage |

| Li et al[16], 2013 | 32 | Pregnancy, mastoiditis | Mechanical thrombectomy combined with urokinase | NA | mRS = 2 at discharge | NA | None |

| Li et al[16], 2013 | 32 | Antithrombin III deficiency, pregnancy | Mechanical thrombectomy combined with urokinase | NA | death | NA | None |

| Li et al[16], 2013 | 26 | Pregnancy | Mechanical thrombectomy combined with urokinase | NA | mRS = 0 at discharge | NA | None |

| Mokin et al[17], 2015 | 33 | Pregnancy | Heparin, penumbra aspiration catheter and separator | Complete restoration of flow | mRS = 2 at discharge | NA | None |

| Mokin et al[17], 2015 | 19 | Pregnancy | Heparin, AngioJet | Partial restoration of flow | mRS = 5 at discharge | NA | None |

| King et al[18], 2016 | 20 | Pregnancy, antithrombin III deficiency | Heparin, mechanical thrombectomy (failed), catheter-directed tPA, heparin + argatroban | Partial restoration of flow | mRS = 2 at discharge | Healthy | None |

| Serna Candel et al[19], 2019 | 34 | Pregnancy, Heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation | LMWH, aspiration thrombectomy (failed), balloon angioplasty (failed), acetylsalicylic acid, eptifibatide, ticagrelor | Partial restoration of flow | mRS = 2 at discharge | Healthy | None |

| Our case | 29 | Pregnancy, antithrombin III deficiency | LMWH, mechanical thrombectomy | Partial restoration of flow | mRS = 1 after 3 mo | Miscarriage | None |

With regard to the safety of radiation exposure on fetal growth during an endovascular procedure, due to the distance between the mother's head and the uterus, the absorbed fetal radiation dose during endovascular treatment was only 2.8 mGy, which was much less than the risk threshold, and this had very little effect on the fetus[20]. The present review showed that the condition of the fetus was not mentioned in half of the 12 pregnant patients. One pregnancy ended in miscarriage, and five fetuses were normal at the time of discharge or follow-up. None of the infants was found to have either congenital anomalies or neonatal morbidity and mortality.

Therapeutic guidelines for CVT in pregnant women are difficult to establish, as the incidence of CVT in pregnancy is rare. If a patient presents with a new persistent headache and abnormalities on neurologic examination during pregnancy, obstetricians and neurologists should consider CVT, and MRI should be performed immediately. If the condition worsens during anticoagulant therapy, mechanical thrombectomy may be a good remedial treatment option.

Cerebral venous thrombosis is easily misdiagnosed or missed due to its rarity, diverse, and non-specific clinical manifestations during pregnancy. Prompt multidisciplinary diagnosis and treatment is essential. Our case and those reported in the literature show that mechanical thrombectomy may be an effective alternative therapy for CVT in pregnant women who do not respond to standard management.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Clinical neurology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jatuworapruk K, Lal A, Patel L, Ramesh PV S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Lindgren E, Jood K, Tatlisumak T. Vocational outcome in cerebral venous thrombosis: Long-term follow-up study. Acta Neurol Scand. 2018;137:299-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ferro JM, Bousser MG, Canhão P, Coutinho JM, Crassard I, Dentali F, di Minno M, Maino A, Martinelli I, Masuhr F, de Sousa DA, Stam J; European Stroke Organization. European Stroke Organization guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis - Endorsed by the European Academy of Neurology. Eur Stroke J. 2017;2:195-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Borhani Haghighi A, Mahmoodi M, Edgell RC, Cruz-Flores S, Ghanaati H, Jamshidi M, Zaidat OO. Mechanical thrombectomy for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a comprehensive literature review. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2014;20:507-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Negro A, Delaruelle Z, Ivanova TA, Khan S, Ornello R, Raffaelli B, Terrin A, Reuter U, Mitsikostas DD; European Headache Federation School of Advanced Studies (EHF-SAS). Headache and pregnancy: a systematic review. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Edlow JA, Caplan LR, O'Brien K, Tibbles CD. Diagnosis of acute neurological emergencies in pregnant and post-partum women. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:175-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | James AH, Bushnell CD, Jamison MG, Myers ER. Incidence and risk factors for stroke in pregnancy and the puerperium. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:509-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 404] [Cited by in RCA: 373] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ferro JM, Canhão P, Stam J, Bousser MG, Barinagarrementeria F; ISCVT Investigators. Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT). Stroke. 2004;35:664-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1336] [Cited by in RCA: 1414] [Article Influence: 67.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kanekar S, Bennett S. Imaging of Neurologic Conditions in Pregnant Patients. Radiographics. 2016;36:2102-2122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Qureshi A, Perera A. Low molecular weight heparin vs unfractionated heparin in the management of cerebral venous thrombosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2017;17:22-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bates SM, Greer IA, Middeldorp S, Veenstra DL, Prabulos AM, Vandvik PO. VTE, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e691S-e736S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1026] [Cited by in RCA: 892] [Article Influence: 68.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ilyas A, Chen CJ, Raper DM, Ding D, Buell T, Mastorakos P, Liu KC. Endovascular mechanical thrombectomy for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a systematic review. J Neurointerv Surg. 2017;9:1086-1092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kourtopoulos H, Christie M, Rath B. Open thrombectomy combined with thrombolysis in massive intracranial sinus thrombosis. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1994;128:171-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chow K, Gobin YP, Saver J, Kidwell C, Dong P, Viñuela F. Endovascular treatment of dural sinus thrombosis with rheolytic thrombectomy and intra-arterial thrombolysis. Stroke. 2000;31:1420-1425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ou YC, Kao YL, Lai SL, Kung FT, Huang FJ, Chang SY, ChangChien CC. Thromboembolism after ovarian stimulation: successful management of a woman with superior sagittal sinus thrombosis after IVF and embryo transfer: case report. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2375-2381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Falavigna A, Pontalti JL, Teles AR. [Dural sinus thrombosis: case report]. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2006;64:334-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li G, Zeng X, Hussain M, Meng R, Liu Y, Yuan K, Sikharam C, Ding Y, Ling F, Ji X. Safety and validity of mechanical thrombectomy and thrombolysis on severe cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Neurosurgery. 2013;72:730-8; discussion 730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mokin M, Lopes DK, Binning MJ, Veznedaroglu E, Liebman KM, Arthur AS, Doss VT, Levy EI, Siddiqui AH. Endovascular treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis: Contemporary multicenter experience. Interv Neuroradiol. 2015;21:520-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | King AB, O'Duffy AE, Kumar AB. Heparin Resistance and Anticoagulation Failure in a Challenging Case of Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis. Neurohospitalist. 2016;6:118-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Serna Candel C, Hellstern V, Beitlich T, Aguilar Pérez M, Bäzner H, Henkes H. Management of a decompensated acute-on-chronic intracranial venous sinus thrombosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019;12:1756286419895157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ishii A, Miyamoto S. Endovascular treatment in pregnancy. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2013;53:541-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |