Published online Sep 22, 2013. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v3.i3.65

Revised: September 14, 2013

Accepted: September 16, 2013

Published online: September 22, 2013

Processing time: 197 Days and 12.5 Hours

AIM: To study the effectiveness of Reitman Centre “Coaching, Advocacy, Respite, Education, Relationship, and Simulation” (CARERS) program, which uses problem-solving techniques and simulation to train informal dementia carers.

METHODS: Seventy-three carers for family members with dementia were included in the pilot study. Pre- and post-intervention data were collected from carers using validated measures of depression, mastery, role captivity and overload, caregiving competence and burden, and coping styles. To assess program effectiveness, mean differences for these measures were calculated. One-way ANOVA was used to determine if change in scores is dependent on the respective baseline scores. Clinical effects for measures were expressed as Cohen’s D values.

RESULTS: Data from 73 carers were analyzed. The majority of these participants were female (79.5%). A total of 69.9% were spouses and 30.1% were children of the care recipient. Participants had an overall mean age of 68.34 ± 12.01 years. About 31.5% of participating carers had a past history of psychiatric illness (e.g., depression), and 34.2% sustained strained relationships with their respective care recipients. Results from carers demonstrated improvement in carers’ self-perception of competence (1.26 ± 1.92, P < 0.0001), and significant reduction in emotion-focused coping (measured by the Coping Inventory of Stressful Situations, -2.37 ± 6.73, P < 0.01), Geriatric Depression scale (-0.67 ± 2.63, P < 0.05) and Pearlin’s overload scale (-0.55 ± 2.07, P < 0.05), upon completion of the Program. Secondly, it was found that carers with more compromised baseline scores benefited most from the intervention, as they experienced statistically significant improvement in the following constructs: competence, stress-coping style (less emotion-oriented), sense of mastery, burden, overload.

CONCLUSION: Study results supported the effectiveness of the CARERS Program in improving caregiving competence, stress coping ability and mental well-being in carers caring for family members with dementia.

Core tip: The “Coaching, Advocacy, Respite, Education, Relationship, and Simulation” (CARERS) Program is a comprehensive package of evidence-based interventions for informal carers comprised of 3 integrated components: group psychotherapy, Problem-Solving Techniques and skill acquisition for specific current challenging interactions in caregiving. The demonstrated outcomes are reduction of emotion-based coping, enhanced mastery, and reduced burden. The Program is structured, and requires active participation of carers as they acquire knowledge and develop caregiving competence. It is the first carer intervention to make systematic use of standardized patients to role play the spouse or parent with dementia, which allows for real-time coaching in managing current, specific, emotionally difficult interpersonal interactions.

- Citation: Chiu M, Wesson V, Sadavoy J. Improving caregiving competence, stress coping, and mental well-being in informal dementia carers. World J Psychiatr 2013; 3(3): 65-73

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v3/i3/65.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v3.i3.65

Informal family carers provide most of the care given to individuals with dementia. In Canada, it has been estimated ninety-seven percent of persons with dementia have at least one carer, the majority being members of their families[1,2]. The value of care they provide has been estimated to be about $26 billion per year[3]. Carers often express satisfaction with their caregiving role[4,5] and their efforts can allow those with dementia to remain at home rather than rely on institutional care[6-9]. However, carers enter the caregiving role generally unprepared with little knowledge of and few skills to deal with dementia. In particular, they often know very little about the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) that almost inevitably emerge during the course of the disease. This knowledge gap is especially significant because many studies report that BPSD are the most challenging feature of dementia for carers and that BPSD contributes most to caregiver burden, which is comprised of the physical, psychological, social and financial hardships experienced by those caring for individuals with dementia[8,10-14]. Caregiver burden, in turn, impairs carers’ problem-solving ability and reduces their caregiving capacity.

Numerous interventions have been proposed to support carers and address caregiver burden. Recent meta-analyses of carer intervention studies suggest that the most effective interventions integrate a variety of techniques which are: structured and intensive; require active participation of carers; include education, support, and respite; promote knowledge transfer, skill building and competency; and take place in both group and individual settings[15-17]. In particular, interventions derived from cognitive-behavioural theory (CBT) appear to have positive effect[18].

Problem-solving therapy (PST) is a structured intervention that is derived from CBT principles and teaches individuals to address problems by systematically examining and finding solutions to problems, without directly focusing on the emotion inherent in challenging situations. PST has been proven effective in reducing negative emotions and moderating distress in family caregivers of persons with severe physical disabilities, in hospice settings and with oncology patients[19-21].

This paper describes the Reitman Centre “Coaching, Advocacy, Respite, Education, Relationship, and Simulation” (CARERS) Program which emphasizes the acquisition and honing of problem-solving skills and the management of emotion-based coping as a method of ameliorating the stress and burden of family caregivers. The theoretical basis and foundation for the CARERS Program is built upon the recognition of the intense emotional challenge of caregiving, the susceptibility of carers to caregiver burden, and the intention to guide them in dealing with impairments in problem-solving and skills deficits in interaction and communication with care recipients. Successful dementia assessment and management requires that the target of care be broadened to include both partners in the carer-care recipient dyad[22]. The CARERS program addresses the needs of carers as a primary focus with comprehensive services designed specifically to address their needs. Integrating formal group psychotherapy principles, formal problem-solving techniques and experiential learning through the novel use of guided simulation, program clinicians aim to address the complex mix of factors that affect carers’ ability to cope with and adapt to the role of carer. Caregiving problems are explicitly defined and targeted with one or both of PST-based intervention and simulations. Program clinicians concurrently attend carefully to carers often intense emotional experiences grounded in loss and grief, acknowledge their efforts, and help normalize the burden inherent in caregiving. At the same time, carers are provided with education regarding dementia as an illness and are assisted in the development of emotional self awareness. Ultimately, the CARERS program aims to minimize emotional and functional impairment of vulnerable carers and to maintain their ability to look after their family members with dementia.

While hospital-based, the program is targeted to community-dwelling family carers and members of their families with dementia. The program is grounded in inter-professional collaboration between psychiatrists, social workers, occupational therapists, educators and researchers at Mount Sinai Hospital (MSH), the Simulated Patient Program at the University of Toronto, and an array of community organizations. The CARERS Program makes use of standardized patients (SPs) to provide carers with a novel learning experience using simulations. It is a vehicle for change in understanding, emotions, and behaviours of individuals who are in conflicted interpersonal situations. Simulation-based coaching is a validated and powerful experiential learning tool traditionally incorporated in health professional educational curricula[23] but has not been commonly used in the therapeutic setting. To our knowledge, the CARERS Program is the first intervention for carers to make systematic use of SPs trained to play the role of persons with dementia for hands-on training of informal carers in behavioural techniques and new ways to approach interpersonal interactions.

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the CARERS intervention on specific measures of change in participating carers, namely: depression[24], mastery, role overload, role captivity, caregiving competence[25], caregiver burden[26], and stress coping style[27,28].

Carers entered the program through self-referral or through referral by hospital or community-based physicians or other health professionals and a wide range of community organizations throughout the Greater Toronto Area, including memory clinics, and social agencies. To be included in the study, the carer had to be a relative of a care recipient who had been usually but not always formally diagnosed with dementia. The care recipient had to be living in a community setting, not necessarily with the carer, but not in a long-term care facility.

The Reitman Centre CARERS program is delivered in 10 weekly small group sessions, each lasting 2.5 h. The small, intensive format group is co-led by two facilitators, both of whom are mental health professionals. Facilitators coach carers through problem-solving and simulation tailored to their personal challenges as well as presenting information in an interactive didactic format when appropriate. Group psychotherapy principles guide management of the often intense emotions which arise in the process. Thus, the method integrates proven group-based psychotherapeutic and educational clinical techniques[29] with an innovative hands-on experiential method employing professional SPs. Carers, guided by the expert clinical coaches, learn how to deal with challenging situations they are encountering at home. The program addresses the need for respite by providing a concurrent interactive arts-based group for the family members with dementia. Carers are further supported through seamless access for both carers and care recipients to state-of-the-art outpatient psychiatric services. Table 1 provides an outline of the objectives and curriculum of the CARERS Program.

| Session | Objective | Description |

| 1 | Building group cohesion and trust Education about dementia | Participants are introduced to the group process and encouraged to connect directly with the facilitators and other group members. They are also introduced to the SP, who will be more actively involved in the therapeutic process beginning in Session 5. In response to their specific questions, participants gain a better understanding of dementia: overview, symptoms and effects on the care-recipients, the carers, and the family. |

| 2-4 | Introduction and elucidation of Problem-solving techniques Objective analysis of individual caregiving problems, and identifying solutions | The key goal of these sessions is to teach the PST method and help carers adopt a problem focused approach rather than less-effective, emotion-focused coping. Facilitator weaves the understanding of emotions described by the carers into the discussions of the PST process to help carers recognize how their emotions may interfere with identifying problems and solving them objectively. Carers are encouraged to implement the solutions at home and report the outcomes of implementation. |

| 5-9 | Skills training Simulations | Through role playing with a SP, carers can practice approaching caregiving challenges differently, focusing in points of interactional conflict and communication. |

| 10 | Skills training, simulation Summing up and termination | Review and recognition of gains made, and acknowledgement of the transition into a new and different phase of supportive care. First maintenance group is scheduled during this session. |

In weeks 1-4, PST and education are the predominant intervention methods. Caregiving problems are explicitly defined and they are taught PST as a method of containing emotions, understanding their problems and finding solutions. As appropriate, carers are educated about brain function and the effect of dementia on behaviour. Throughout the 10-wk intervention, less structured focal psychotherapeutic interventions address significant emotional issues when they arise is the group.

A quasi-experimental pre-post treatment design was used. A control group was not included in this demonstration program.

Prior to the first group session, an intake assessment of the carer and care recipient was conducted by program clinicians. At this meeting, in addition to gathering demographic data and developing an understanding of the specific caregiving challenges faced, the clinician administered a baseline series of standardized outcome measures to the carer. The same series of outcome measures were repeated in a post-intervention interview within 1 mo of the last session of the program.

The standardized assessment tools used to evaluate outcomes have been widely used and their properties are well-established. These assessments were depression (15-item Geriatric Depression scale)[25], mastery, role overload, role captivity, caregiving competence[26], caregiver burden (12-item Zarit Burden Interview)[27], and stress coping style (The Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations)[28,29]. Details of outcome measures are presented in Table 2.

| Instrument | Descriptions | Ref. |

| 15-item geriatric depression scale | Validated and widely applied in older populations in community, acute and long-term care settings. | [35,36] |

| Fifteen questions from the Long Form GDS which had the highest correlation with depressive symptoms in validation studies were selected for the Short Form GDS. | ||

| Scores of 0-4 are considered normal; 5-8 indicate mild depression; 9-11 indicate moderate depression; and 12-15 indicate severe depression. | ||

| Self-mastery scale | Self-mastery is a perception that reflects one’s personal mastery or control over life outcomes | [26] |

| Seven items are scored on a 4-point (agree-disagree format) scale with two items recoded in the opposite direction to produce scores ranging from 7 to 28. | ||

| In the current study, Mastery score was calculated using a negative-oriented scale (i.e., response to positively phrased questions were reverse-coded). Thus, lower scores indicate higher self-mastery. | ||

| Role captivity scale | Three-items scale assesses degree of entrapment which carers perceive in their caregiving role. | [26] |

| A 4-point Likert scale is used to document the extent to which carers may feel constrained in their caregiving role during the past week. | ||

| Scores may range from 3 to 12, with higher scores indicating more role captivity. | ||

| Role overload scale | Four-item scale that reflects how carers may be overwhelmed as their time and energy level are being exhausted by the demands of caregiving. | [26] |

| A 4-point Likert scale reports extent to which carers may feel overloaded in the past week. | ||

| Scores may range from 4 to 16, with higher scores indicating more overload. | ||

| Caregiving competence scale | Four-item scale measures carers’ self-perception of his/her ability to carry out carer role properly. | [26] |

| A 4-point Likert scale reports the level of competence. | ||

| 12-item zarit burden interview | Covers multiple domains: financial difficulties, social life, physical and psychological health, and the relationship between the persons with dementia and the carer. | [14] |

| A 5-point Likert scale assesses level of burden experienced by carers | ||

| Total burden scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores reflecting greater caregiver burden. | ||

| Coping inventory for stressful situations | 48-item measure describes the manner in which an individual responds to stressful situations. It measures three forms of coping style: emotion-focused, task-oriented, avoidance-oriented | [28,29] |

| For each coping strategy, respondents rate the usage frequency on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). |

History of past psychiatric illness and pre-morbid relationship between the carer and the care recipients were also routinely inquired about during the intake assessment, and included in each carer’s clinical record. These records were reviewed and information regarding psychiatric history were extracted and included in data analysis for the current study.

Research ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Mount Sinai Hospital Research Ethics Board, a member of the Toronto Academic Health Sciences Network. All participants provided informed consent to data collection and publications of data.

To assess the effectiveness of the CARERS program, mean ± SD for the assessment tools listed above were calculated. The unit of analysis was the family carer. Simple descriptive analysis was performed for the baseline demographics. Paired t-tests were used to compare baseline scores and follow-up scores upon completion of the program. The change in scores was calculated as the post-program score minus the baseline score. P < 0.05 indicates a clinically significant change in the score.

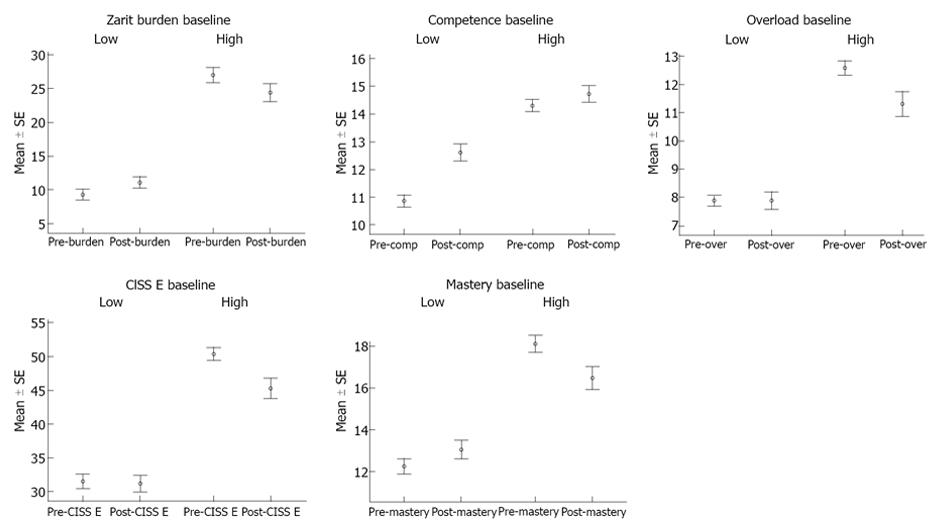

In order to determine if the change in scores for each of these outcome measures is dependent on the baseline score, one-way ANOVA was performed for each outcome measure with score difference as dependent variable and baseline score as the independent variable. For outcome measures without established standard clinical cut-off scores, the mean score for the outcome measure was calculated and used as the arbitrary cut-off for the corresponding baseline score. For example, the mean Competence score was calculated to be 11.9, and arbitrary cut-off for the measure was set at 12 for the purpose of the current study (i.e., 0-12 low sense of competence; > 12 high sense of competence).

To determine the clinical relevance of the changes, outcomes measures were stratified by their respective baseline scores, and the clinical effects for the stratified groups were calculated for each outcome measure and expressed as Cohen’s D values. From a clinical perspective, an effect size of 0.56-1.2 can be interpreted as a large effect, while effect sizes of 0.33-0.55 are moderate, and effect sizes of 0-0.32 are small[30]. Data were analyzed using SPSS, Version 19, IBM Corporation.

Data from 73 carers from the first 22 groups to complete the Program have been analyzed. All of these participants attended at least 8 of the 10 sessions. Reasons for absence included conflicts in scheduling and health problems of the carers or the care recipients. The majority of these participants were female (79.5%). A total of 69.9% were spouses and 30.1% were children of the care recipient. Participants had an overall mean age of 68.34 ± 12.01 years (mean age of adult children is 55.09 ± 11.51 years and mean age of spouses is 72.87 ± 8.41 years). According to carers’ clinical records obtained during intake assessment, 31.5% of participating carers had a past history of psychiatric illness (e.g., depression), and 34.2% reported strained relationships with their respective care recipients.

Table 3 reports the results of a pre-intervention versus post-intervention t-test analysis on the carers’ outcome measures, taken prior to and within one month of the last session. Mean differences between pre- and post-scores for competence (1.26 ± 1.92, P < 0.0001), emotion-focused coping style (-2.37 ± 6.73, P < 0.01), geriatric depression score (-0.67 ± 2.63, P < 0.05) and Pearlin’s overload (-0.55 ± 2.07, P < 0.05) were statistically significant.

| Mean scores pre- and post-intervention | Change from baseline | ||||

| Measures | n | Baseline | Post | mean ± SD | Pvalue |

| CISS A (-)1 | 68 | 40.59 ± 9.70 | 40.49 ± 10.26 | -1.03 ± 5.97 | 0.887 |

| CISS E (-) | 68 | 39.65 ± 11.21 | 37.28 ± 10.49 | -2.37 ± 6.73 | 0.005 |

| CISS T (+) | 68 | 57.72 ± 9.02 | 56.76 ± 8.94 | -0.96 ± 7.99 | 0.327 |

| Competence (+) | 70 | 12.14 ± 2.12 | 13.40 ± 2.07 | 1.26 ± 1.92 | < 0.0001 |

| Geriatric depression scale | 64 | 4.70 ± 3.89 | 4.03 ± 3.70 | -0.67 ± 2.63 | 0.045 |

| Mastery (-)2 | 70 | 14.76 ± 3.69 | 14.51 ± 3.32 | -0.24 ± 2.54 | 0.426 |

| Overload (-) | 67 | 9.93 ± 2.67 | 9.37 ± 2.71 | -0.55 ± 2.07 | 0.032 |

| Role captivity (-) | 69 | 7.42 ± 2.68 | 7.29 ± 3.23 | -0.13 ± 2.20 | 0.623 |

| Zarit burden (-) | 67 | 19.87 ± 10.61 | 19.04 ± 9.54 | -0.82 ± 6.87 | 0.332 |

Carers who entered the Program faring worse (i.e., those with worse baseline scores based on the standard or arbitrary cut-off scores) in certain constructs appeared to benefit most from the intervention. Upon completion of the 10-wk program, carers who had worse baseline scores in the following constructs experienced statistically significant improvement: competence, stress-coping style (less emotion-oriented), sense of mastery, burden, overload. These treatment effects are represented in separate graphs in Figure 1. To quantify these treatment effects, outcomes measures were stratified by their respective baseline scores, and the clinical effects for the two stratified groups were calculated for each outcome measure and expressed as Cohen’s D values, which are shown in Table 4. The D values of the aforementioned constructs (competence, emotion-oriented coping, sense of mastery, burden, overload) all fall in the moderate to large clinical effect range (0.33-1.2) in their respective “more compromised” strata.

| Clinical effect (Cohen’s D) | |||||

| n | Standard/arbitrary cut-off | P value | More “Compromised” baseline;(mean score; Cohen’s D) | Less “Compromised” baseline;(mean score; Cohen’s D) | |

| Measures with standard cut-off | |||||

| Geriatric depression scale | 64 | 5[37] | 0.074 | 9.00 ± 2.42; D = -0.58 | 2.14 ± 1.60; D = -0.022 |

| zarit burden | 67 | 15[38] | 0.015 | 27.00 ± 6.93; D = -0.34 | 14.30 ± 1.10; D = 0.42 |

| Measures with arbitrary cut-off | |||||

| CISS A | 68 | 40 | 0.40 | 49.74 ± 5.95; D = -0.15 | 33.00 ± 4.55; D = 0.077 |

| CISS E | 68 | 40 | 0.003 | 50.26 ± 5.10; D = -0.74 | 31.55 ± 6.58; D = -0.045 |

| CISS T | 68 | 55 | 0.004 | 48.52 ± 5.83; D = 0.38 | 63.38 ± 6.37; D = -0.47 |

| Competence | 70 | 12 | 0.012 | 10.82 ± 1.40; D = 1.06 | 14.30 ± 1.10; D = 0.33 |

| Mastery (negative-oriented scale) | 70 | 15 | 0.022 | 18.10 ± 2.30; D = -0.62 | 12.21 ± 2.23; D = 0.34 |

| Overload | 67 | 10 | 0.011 | 12.59 ± 1.35; D = -0.69 | 7.98 ± 1.20; D = -0.058 |

| Role captivity | 69 | 7 | 0.332 | 9.74 ± 1.48; D = -0.22 | 5.32 ± 1.42; D = 0.10 |

This paper describes the CARERS Program, a carer intervention designed to emphasize the acquisition and honing of problem-solving, interpersonal and communication skills and the reduction of emotion-based coping in order to ameliorate the stress and burden of caregiving. Based on the data it appears that equipping informal carers with the necessary coping skills, knowledge and techniques can increase caregiving capacity.

The CARERS Program was able to produce a statistically significant reduction in carers’ emotion-focused stress coping (-2.37 ± 6.73, P < 0.01). Emotions impair carers’ ability to understand and manage problems, diminish their ability to seek social support and reduce their sense of mastery and control. Hence, emotion focused coping, which uses emotional reactions to reduce the stress caused by problems, is often maladaptive and produces a downward spiral: poor problem-solving skills may lead to a more negative perception of a stressful situation which can compromise caregiving capacity, increase emotional distress and further impair problem-solving skills. The CARERS Program trains carers to apply problem-solving techniques in the identification of specific caregiving challenges and development of effective, adaptive solutions for them. Thus, carers may depend less on emotions when coping with stress, adopt a more effective task-focused stress coping style and learn to solve problems directly through cognitive re-conceptualization, management of their impact and generation of realistic, practical solutions. As might be predicted by the underlying premise of problem-solving techniques that feelings of stress, burden, depression and anxiety are linked, this proactive approach seems to have a positive impact on carers’ mental well-being, causing carers to feel less depressed and overloaded[31,32].

Carers who participated in the Program also experienced a robust improvement in self-perceived level of caregiving competence (1.26 ± 1.92, P < 0.0001). Competence is a measure of the efficacy of the simulation component of the Program. The use of simulations in the CARERS Program arises from the foundational evidence that demonstrates that the most effective interventions for teaching caregiving skills combine direct observation and coaching of carers as they respond to challenging situations while simultaneously using the group process to integrate the exploration and understanding of individual carer’s emotional reactions[23]. A related core principle of the Program is that the stress of caregiving can be ameliorated by attending to specific challenges as perceived by the individual carer. Simulations allow each carer to receive real time coaching in the management of the challenges unique to them. Factors that impede effective caregiving and communication with the person with dementia can then be modified by education, interpretation, coaching and practice[33]. Through repeated practice, skills are developed, polished and retained. Simulation also encourages application in real life situation.

This study did not demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in caregiver burden in the study sample as a whole, perhaps because the mean baseline level of burden was low (mean of 19.87 on a scale of 0 to 60, Table 3). However, carers whose baseline level of burden was higher (mean score of 27.00 ± 6.93) had a significant drop in their burden scores (Cohen’s D = -0.34). Also, as indicated by the Cohen’s D values, it appeared that the Program was particularly effective in helping the most distressed carers since those who entered the Program faring worse also experienced statistically significant improvement in sense of mastery and levels of caregiver burden and overload in addition to improved caregiving competence and reduced emotion focused coping. These preliminary data suggest that screening for severity of the above constructs might provide valuable information to guide subsequent therapeutic interventions.

The study has a number of limitations. It lacked a control group thus making it impossible to rule out the possibility that other factors, such as the passage of time or regression to the mean, contributed to the improvements noted over the course of the Program. Future plans include the implementation of a time-rolling control group of carers assessed and accepted for the Program who are waiting to begin. A second difficulty lies in the fact that carers found the number of outcome measures and the emotions they evoked to be difficult to tolerate. The results of the current work will allow the evaluation of which measures capture the salient changes in participants. This will allow the development of a more streamlined package of outcome measures. A third limitation is that the care recipients were not evaluated either before or after participation in the Program. Thus, it is not possible to state whether the development of carers’ problem-solving and other caregiving capacities translated into meaningful improvement in care recipient outcomes.

This was a proof of concept pilot delivered in a single location by professionals who were also integral to the Program’s conceptualization and development. In such situations, it might be difficult or impossible to replicate the intervention and its success in other sites. However, it can be reported that the program has been successfully disseminated in various other settings. Professionals in other organizations in other locations have been taught the skills of the CARERS method to develop and deliver the Program and have been successful in setting up programs for carers at their sites. Further, the Program has been successfully replicated in another language (Cantonese) in two institutions providing care to Chinese carers and their family members with dementia. Broader dissemination is planned in populations of more vulnerable carers such as those belonging to a different ethnic group with unique cultural needs or those living in remote or rural areas without direct access to tertiary care[34].

The principal and predominant approach of the Reitman Centre CARERS Program is to train carers for the unfamiliar role into which they have been thrust. The theoretical rationale is that insufficient skills and knowledge, emotion-focused coping and distress, and breakdown in problem-solving ability with loss of sense of control and feeling trapped are at the core of caregiver burden. To address these complex factors a comprehensive integrated package of evidence-informed interventions were developed which are structured and intensive, require active participation of carers; include education, support, and respite; promote knowledge transfer, skill building and competency; and delivered in a group therapy setting.

Evaluation results provide support for the effectiveness of the CARERS Program in improving competence, stress coping ability and mental well-being in carers taking care of family members with dementia. The intervention was shown to be well-received by carers. To refine validity of outcome data, the next phase of program evaluation is underway with the inclusion of a control group. Broader dissemination is planned in populations of more vulnerable carers such as those belonging to a different ethnic group with unique cultural needs or those living in remote or rural areas without direct access to tertiary care.

Informal family carers provide most of the care given to individuals with dementia. Health care systems for dementia could not function without effective family carers. However, family carers are a vulnerable group at disproportionate risk of developing psychological and physical problems associated with providing care and are in need of services designed specifically for them. It has been demonstrated that interventions for carers are effective in increasing their caregiving capacities and resilience and improving their lives and those of their loved ones. While carers have not previously been considered to be a group with legitimate health-care needs, it is clear that the care of carers is a necessary component of the system of care of individuals with dementia. Sustaining carers and improving their effectiveness by maximizing their abilities and minimizing their burden will ensure that they can continue to look after their family members with dementia.

Many interventions have been developed and shown to be effective in supporting carers. The research hotspot is how to develop an new intervention that incorporates and integrates efficacious elements of past programs to help careers deal with the emotional consequences of caregiving for a loved-one with dementia, improve their problem solving skills and minimize emotion-focused coping and distress, enhance their skills in managing the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, teach them about dementia, and, in so doing, increase carer competence and coping capacity, sense of mastery and control and overall psychological well being.

The Reitman Centre “Coaching, Advocacy, Respite, Education, Relationship, and Simulation” (CARERS) Program is a unique, therapeutic-skills-training program. It is a comprehensive integrated package of evidence informed interventions for vulnerable family carers designed to emphasize the acquisition and honing of problem-solving, interpersonal and communication skills and the reduction of emotion-based coping with the goal of reducing caregiver burden. It is structured, intensive and requires active participation of carers as they acquire knowledge and develop caregiving skills and competence. The Program is built on three foundational principles: one, that caregiving is an intensely emotionally challenging process for family carers, two, that the stress of caregiving can be ameliorated by attending to specific challenges encountered by the individual carer; and three, that the most effective interventions for teaching caregiving skills combine direct observation and coaching of carers as they respond to challenging situations. The Program is the first carer intervention to make systematic use of standardized patients to play the role of persons with dementia for hands-on, real time coaching in managing specific, difficult interpersonal interactions. Formal problem solving therapy techniques are also used to define and address each carer’s unique challenges. At the same time, therapeutic group process is used to assist carers in developing emotional self-awareness and normalizing the burden inherent in caregiving.

Broader dissemination of the program is underway in other populations of carers at risk in diverse cultures and geographical locations. The Reitman Centre also serves as a centre for the education of health professionals interested in learning the CARERS methods.

Caregiver burden is the combination of the physical, psychological, social and financial hardships experienced by those caring for someone with dementia. Problem solving therapy (PST) is a structured intervention derived from Cognitive Behavioural Therapy principles that teaches individuals to address problems by systematically examining and finding solutions, without directly focusing on the emotion inherent in challenging situations. PST has been proven effective in reducing negative emotions and moderating distress in family caregivers in a variety of caregiving situations. Standardized patients are healthy individuals trained to portray the personal history, physical symptoms, emotional characteristics and every day concerns of an actual patient.Simulation based coaching is a validated and powerful experiential learning tool traditionally incorporated in health professional education curricula. It is a vehicle for change in understanding, emotions and behaviours of individuals who are in conflicted interpersonal situations.

The authors described the pilot research of the Reitman Centre CARERS Program, which uses problem-solving techniques and simulation for hands on skills training in informal caregivers. They concluded that their results supported the effectiveness of the Program in improving caregiving competence, stress coping ability and mental well-being in carers caring for family members with dementia.

P- Reviewer: Shinagawa S S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Cranswick K. General social survey cycle 16: caring for an aging society. : Statistics Canada, Housing, Family and Social Statistics Division 2003; . |

| 2. | Canadian Institute for Health Information. Caring for seniors with Alzheimer's Disease and other forms of Dementia, cited 2012-08-08. Available from: http://www.cihi.ca. |

| 3. | Hollander MJ, Liu G, Chappell NL. Who cares and how much? The imputed economic contribution to the Canadian healthcare system of middle-aged and older unpaid caregivers providing care to the elderly. Healthc Q. 2009;12:42-49. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Kramer BJ. Gain in the caregiving experience: where are we? What next? Gerontologist. 1997;37:218-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cohen CA, Colantonio A, Vernich L. Positive aspects of caregiving: rounding out the caregiver experience. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:184-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 386] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cranswick K, Dosman D. Eldercare: What we know today. Canadian social trends. 2008;86:49-57. |

| 7. | Mittelman MS, Haley WE, Clay OJ, Roth DL. Improving caregiver well-being delays nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:1592-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in RCA: 370] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Spurlock WR. Spiritual well-being and caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s caregivers. Geriatr Nurs. 2005;26:154-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stone R, Cafferata GL, Sangl J. Caregivers of the frail elderly: a national profile. Gerontologist. 1987;27:616-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 717] [Cited by in RCA: 537] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | George LK, Gwyther LP. Caregiver well-being: a multidimensional examination of family caregivers of demented adults. Gerontologist. 1986;26:253-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 930] [Cited by in RCA: 803] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schulz R, O’Brien AT, Bookwala J, Fleissner K. Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: prevalence, correlates, and causes. Gerontologist. 1995;35:771-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1179] [Cited by in RCA: 1106] [Article Influence: 36.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, Gornbein J. The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1996;46:130-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 683] [Cited by in RCA: 652] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Donaldson C, Burns A. Burden of Alzheimer’s disease: helping the patient and caregiver. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1999;12:21-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20:649-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3184] [Cited by in RCA: 3343] [Article Influence: 74.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: which interventions work and how large are their effects? Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;18:577-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 599] [Cited by in RCA: 502] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Schoenmakers B, Buntinx F, Delepeleire J. Factors determining the impact of care-giving on caregivers of elderly patients with dementia. A systematic literature review. Maturitas. 2010;66:191-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sörensen S, Pinquart M, Duberstein P. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2002;42:356-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 751] [Cited by in RCA: 652] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cooper C, Balamurali TB, Selwood A, Livingston G. A systematic review of intervention studies about anxiety in caregivers of people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:181-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Demiris G, Oliver DP, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Washington K. Use of videophones to deliver a cognitive-behavioural therapy to hospice caregivers. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17:142-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sahler OJ, Fairclough DL, Phipps S, Mulhern RK, Dolgin MJ, Noll RB, Katz ER, Varni JW, Copeland DR, Butler RW. Using problem-solving skills training to reduce negative affectivity in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: report of a multisite randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:272-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Elliott TR, Berry JW, Grant JS. Problem-solving training for family caregivers of women with disabilities: a randomized clinical trial. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:548-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sadavoy J, Wesson V. Refining Dementia Intervention: The Caregiver-Patient Dyad as the Unit of Care. CMAJ. 2012;2:5-10. |

| 23. | McNaughton N, Ravitz P, Wadell A, Hodges BD. Psychiatric education and simulation: a review of the literature. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:85-93. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. 9/Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) Recent Evidence and Development of a Shorter Violence. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:165-173. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3109] [Cited by in RCA: 3176] [Article Influence: 186.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30:583-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2729] [Cited by in RCA: 2761] [Article Influence: 78.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O’Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001;41:652-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 882] [Cited by in RCA: 1101] [Article Influence: 45.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Endler NS, Parker JD. Multidimensional assessment of coping: a critical evaluation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;58:844-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1027] [Cited by in RCA: 829] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Endler NS, Parker JD, Butcher JN. A factor analytic study of coping styles and the MMPI-2 content scales. J Clin Psychol. 1993;49:523-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gallagher-Thompson D, Coon DW, Solano N, Ambler C, Rabinowitz Y, Thompson LW. Change in indices of distress among Latino and Anglo female caregivers of elderly relatives with dementia: site-specific results from the REACH national collaborative study. Gerontologist. 2003;43:580-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates 2005; . |

| 31. | Nezu AM. Efficacy of a social problem-solving therapy approach for unipolar depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54:196-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | D'Zurilla TJ. Problem-solving training for effective stress management and prevention. J Cogn Psychother. 1990;4:327-354. |

| 33. | Sadavoy J, Wesson V, Nelles LJ. The Reitman Centre CARERS Program: A Training Manual for Health Professionals. New York: Mount Sinai Hospital 2012; . |

| 34. | Thinnes A, Padilla R. Effect of educational and supportive strategies on the ability of caregivers of people with dementia to maintain participation in that role. Am J Occup Ther. 2011;65:541-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 1982-. 1983;17:37-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8972] [Cited by in RCA: 9281] [Article Influence: 215.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Greenberg SA. How to try this: the Geriatric Depression Scale: Short Form. Am J Nurs. 2007;107:60-69; quiz 69-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Meara J, Mitchelmore E, Hobson P. Use of the GDS-15 geriatric depression scale as a screening instrument for depressive symptomatology in patients with Parkinson’s disease and their carers in the community. Age Ageing. 1999;28:35-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Higginson IJ, Gao W, Jackson D, Murray J, Harding R. Short-form Zarit Caregiver Burden Interviews were valid in advanced conditions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:535-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |