Published online Aug 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i8.102835

Revised: March 19, 2025

Accepted: March 20, 2025

Published online: August 19, 2025

Processing time: 182 Days and 1.2 Hours

The development of prostate cancer (PC) frequently intensifies negative emotional states, such as anxiety and depression, which compromise the effectiveness of radical surgery and reduce treatment adherence. In this study, we hypothesized that psychological resilience plays a crucial role in this process and explored its impact.

To investigate the association of resilience with anxiety and depression in patients with PC and to analyze the influencing factors.

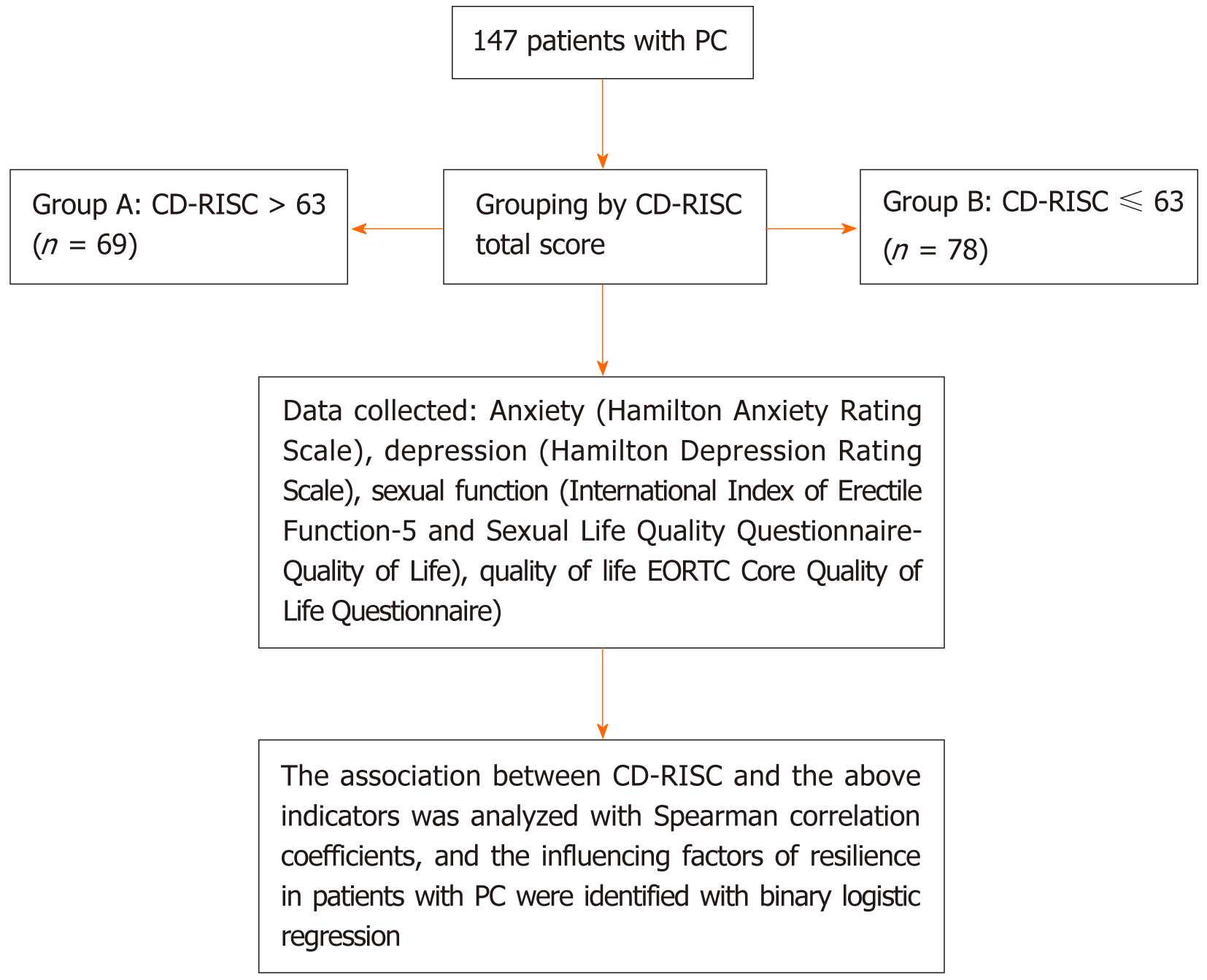

We selected 147 patients with PC who visited Qingdao Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital from January 2022 to June 2024. The resilience scores of patients with PC were assessed using the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) from the tenacity, self-improvement, and optimism dimensions. Based on the total CD-RISC score, patients were categorized into groups A (total CD-RISC score > 63 points, n = 69) and B (total CD-RISC score ≤ 63 points, n = 78) for com

Group A demonstrated statistically lower HAMA and HAMD scores and markedly higher scores of IIEF-5, SLQQ-QOL, and various QLQ-C30 aspects. Correlation analysis revealed that CD-RISC was significantly negatively correlated with HAMA and HAMD scores and significantly positively correlated with IIEF-5, SLQQ-QOL, and QLQ-C30 total scores. Binary logistic regression analysis revealed educational and per capita monthly household income levels as significant influencing factors of resilience in patients with PC.

Our results indicate a significant correlation of resilience with anxiety and depression in patients with PC. The milder the anxiety and depression emotions in patients, the higher their resilience. Further, assisting patients with PC to improve their educational and per capita monthly household income levels will help their resilience to some extent.

Core Tip: Psychological resilience is an individual’s capacity to adapt to stressors and counteract the detrimental effects of future adverse events. In patients with prostate cancer, resilience acts as a protective buffer, facilitating effective emotional regulation and alleviating emotional distress. Despite its importance, research that examined the association between psychological resilience and anxiety or depression in patients with prostate cancer as well as the factors influencing this association remains limited. Our study reveals that higher psychological resilience levels are strongly associated with reduced anxiety and depression, improved sexual function, and enhanced overall quality of life. Furthermore, factors, such as higher educational attainment and greater monthly household income per capita positively contribute to the development of psychological resilience in these patients.

- Citation: Qu JL, Lu HY, Fu XB, Gai WT. Correlation of resilience with anxiety and depression in patients with prostate cancer and analysis of influencing factors. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(8): 102835

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i8/102835.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i8.102835

Prostate cancer (PC) constitutes 13.5% of all male-related tumors, and the global cumulative lifetime risk of men developing this disease is 3.7%[1]. Relevant data statistics reported approximately 1.3 million patients with PC globally in 2018, with approximately 29.3 patients with PC per 100000 men[2,3]. Factors, such as race, genetic factors, obesity, smoking, and excessive dairy intake, all predispose to PC and further increase the risk of men developing PC[4]. The occurrence of PC causes adverse clinical manifestations, such as sexual dysfunction, upper urinary tract damage, and even urinary incontinence, in men[5]. This not only strongly affects patients’ physical and mental health and exacerbates their negative emotions, such as anxiety, depression, fear, and helplessness, but also compromises the therapeutic effect of radical surgery and treatment compliance, thereby posing a serious threat to their quality of life[6,7]. Detailed data indicated that over 16.0% of patients with PC experience significant depressive symptoms with a 6.5 times higher risk of suicide within the first 6 months of developing the disease than that of the general population, in addition to an increased risk of sleep disorders[8-10]. Resilience is an individual’s ability to cope with stressors and resist the harmful effects of future negative events, which buffer stress-related depression and, to a certain extent, help patients with PC reduce distress[11,12]. Groarke et al[13] revealed resilience as a protective factor that helps patients with PC to buffer pressure, realize effective emotional regulation, and effectively reduce emotional distress. Further, resilience assists individuals in restoring optimism and tranquility when confronted with events such as chronic pain, the aging process, and terrorist attacks[14-16]. Research on the correlation of resilience with anxiety and depression in patients with PC and the investigation of influencing factors is currently limited. This study fills the crucial gaps by conducting relevant analysis and is committed to improving the physical and mental health of patients with PC.

Participants consisted of 147 patients with PC admitted to Qingdao Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital from January 2022 to June 2024. They were categorized based on the total score of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Group A consisted of patients with a total CD-RISC score of > 63 (n = 69), whereas group B included those with a total CD-RISC score of ≤ 63 (n = 78). The research flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

Inclusion criteria: (1) PC diagnosis based on imaging and pathological specimens; (2) Ability to normal reading comprehension and independently completing the scale survey; (3) Meeting the surgical indications for laparoscopic radical prostatectomy; and (4) Intact clinical data.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Unstable or rapidly deteriorating condition; (2) Other malignant tumors; (3) Alcohol and drug dependence; and (4) Coagulation dysfunction and autoimmune system deficiencies.

Resilience: The CD-RISC scale compiled by Connor and Davidson was used for resilience assessment. The 25-item instrument consists of three dimensions (tenacity, self-improvement, and optimism with 13, 8, and 4 items, respectively) and uses a 5-point Likert scale.

Psychological state: The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAMA) and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) were employed to assess patients’ anxiety and depression, consisting of 14 items and 17 items with a cut-off value of 14 points and 17 points, respectively. Both scales are rated on a 5-point scale (0-4 points), with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety or depression.

Sexual function: The International Index of Erectile Function-5 (IIEF-5) and the Sexual Life Quality Questionnaire-Quality of Life (SLQQ-QOL) were used for sexual function assessment. IIEF-5 consists of 5 items with a total score of 25 points, whereas SLQQ-QOL consists of 10 items, each scored on a 4-point scale. A higher score on either scale indicates better sexual function.

Quality of life: The EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) was used for assessment. This scale comprises five functional dimensions: Physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social functions. A higher score indicates a better quality of life.

The scale surveys were performed in a controlled and private setting, with patients seated in either independent consultation rooms or hospital wards to ensure a quiet, well-lit, and distraction-free environment. Privacy curtains or separate partitions were utilized to prevent any external observation. Encrypted tablets were used for electronic data collection, whereas paper questionnaires were securely sealed by patients in confidential envelopes. To minimize fatigue-induced response bias, the survey duration for each patient was carefully maintained within 20-30 minutes. Two physicians, who had received standardized training, administered the surveys. The training program included instruction on consistent scale interpretation, the use of neutral language, and strategies for providing emotional reassurance to patients. Crucially, these investigators were not involved in the clinical treatment of participants and were blinded to the study hypotheses, thereby reducing the potential for subjective bias or undue influence on patient responses.

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 22.0 statistical software was used for data analysis in this study. Measurement data were statistically described as mean ± SEM. The t-test was used for comparing measurement data between groups. Count data were statistically described by frequency (percentage). The χ2 test was conducted to compare count data between the two groups. Binary logistic regression was applied to analyze the influencing factors of resilience in patients with PC. A P value of < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference. For binary logistic regression analysis, the sample size is recommended to be at least 10 times the number of predictor variables. A minimum of 50 samples was required in this study, which included five predictor variables. This study significantly exceeded the minimum sample size requirement by enrolling 147 cases, thereby ensuring robust statistical power for the analysis.

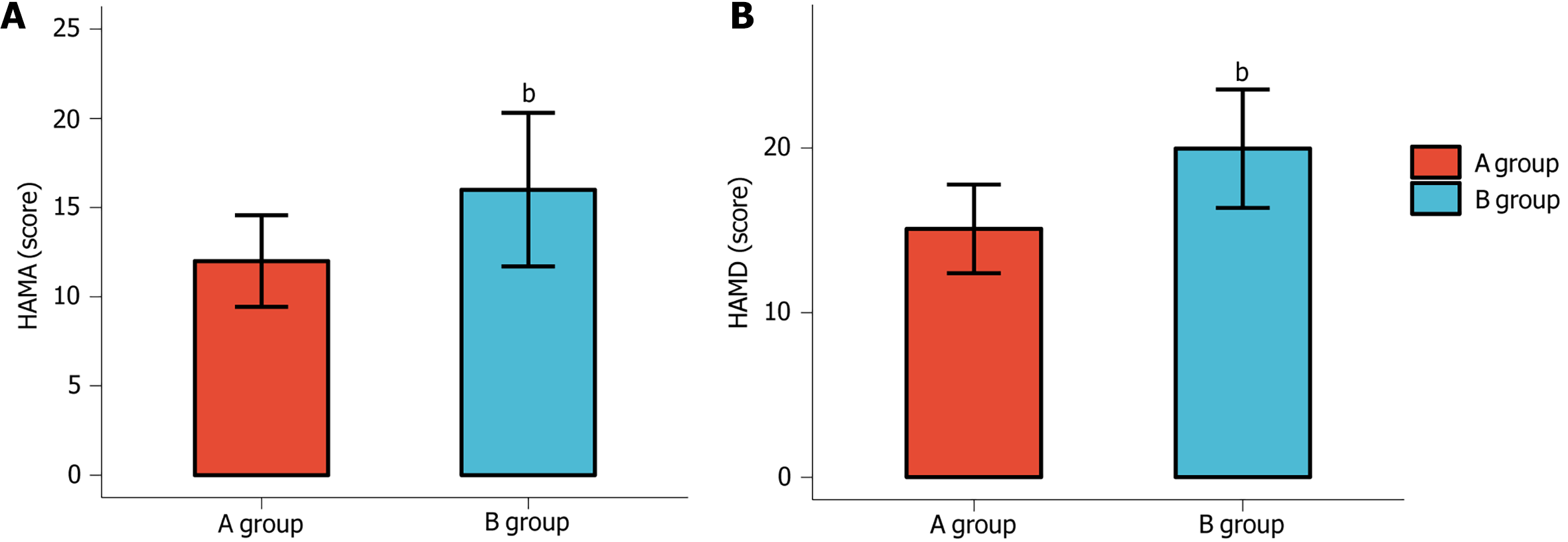

Group A demonstrated reduced HAMA and HAMD scores compared with group B, with statistically significant dif

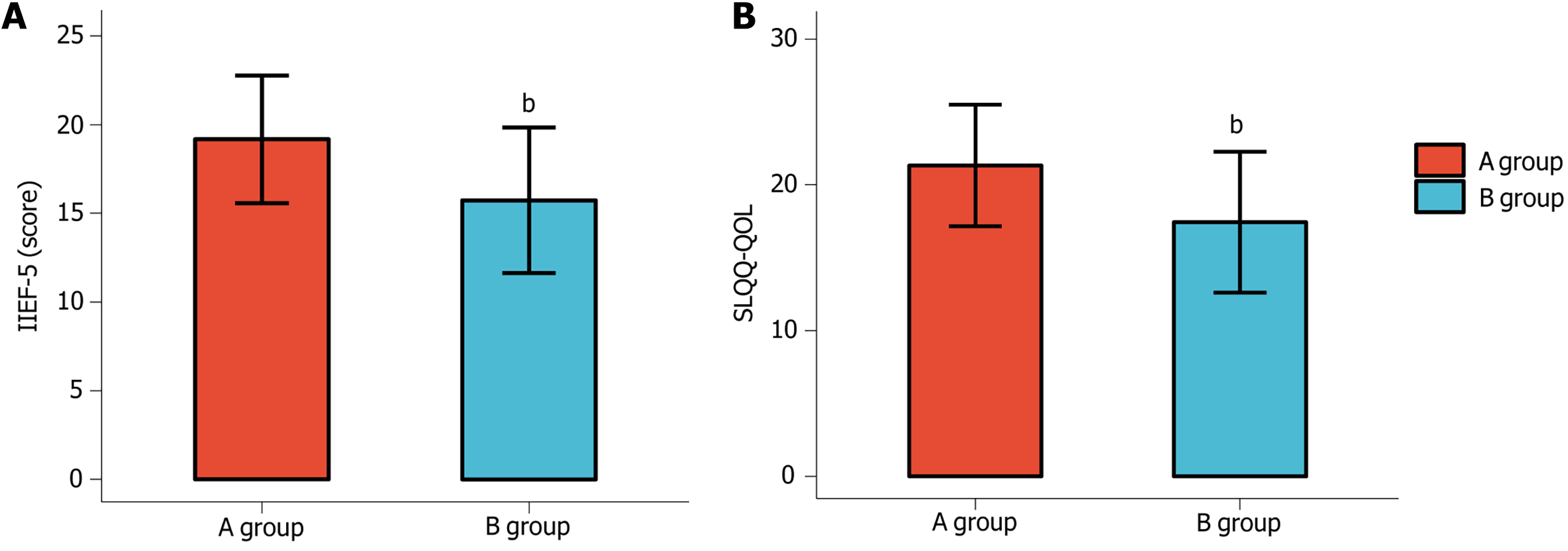

The sexual function assessment of the two groups using the IIEF-5 and SLQQ-QOL scales revealed that group A demonstrated significantly higher IIEF-5 and SLQQ-QOL scores than group B (P < 0.01) (Figure 3).

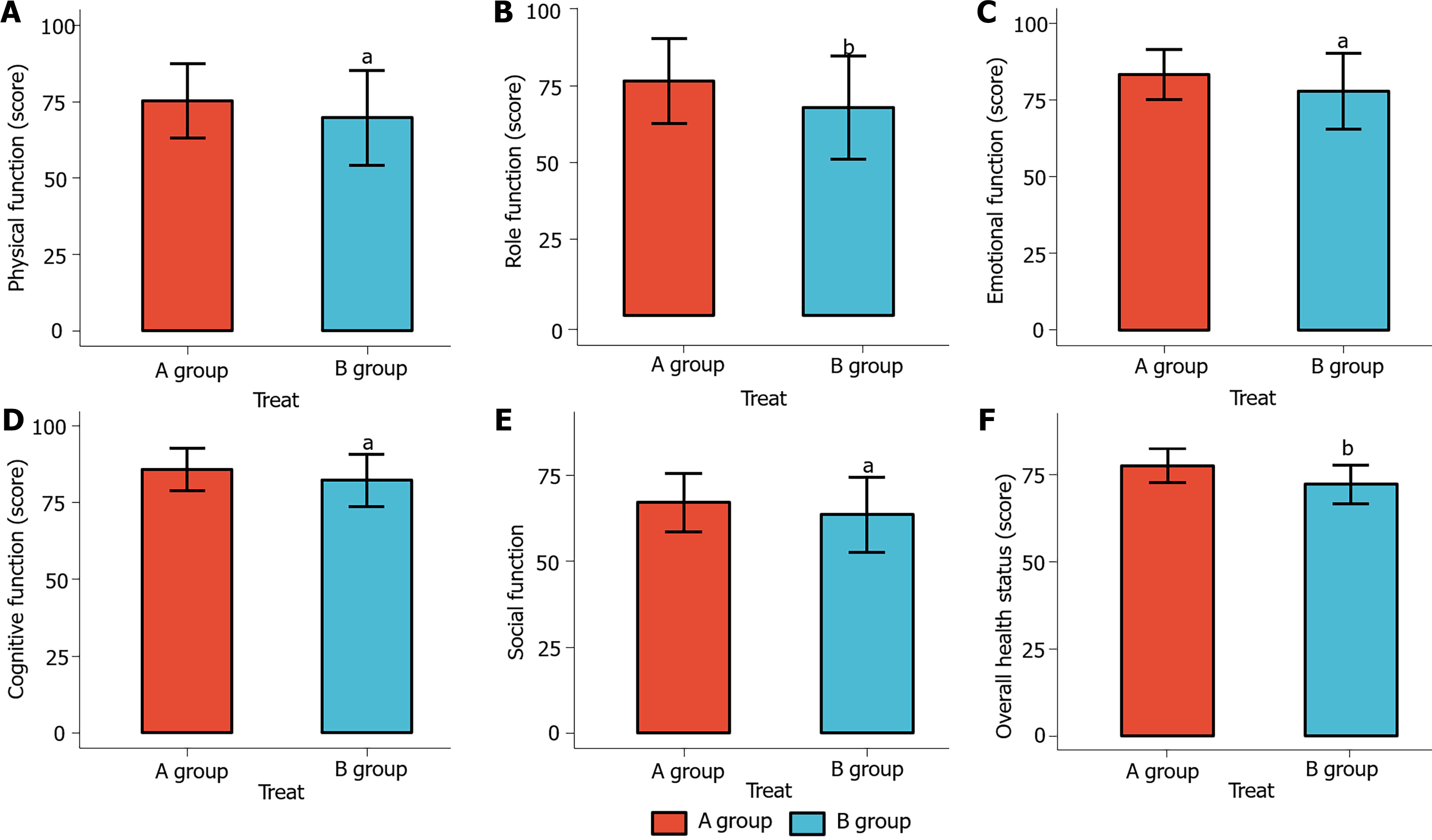

The QLQ-C30 scale was used to assess the quality of life levels between the two groups in terms of physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social function aspects as well as overall health status. The data indicated that group A exhibited significantly higher QLQ-C30 scores in each of the above dimensions compared to group B (P < 0.05) (Figure 4).

Spearman correlation coefficients were used to analyze the correlation between resilience and various indicators. Resilience demonstrated a significant inverse correlation with anxiety and depression (r = -0.544, P < 0.001; r = -0.619, P < 0.001) and a significant positive association with the two sexual function scales (r = 0.396, P < 0.001; r = 0.390, P < 0.001) as well as the quality of life (r = 0.460, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

| Variable | r | P value |

| HAMA | -0.544 | < 0.001 |

| HAMD | -0.619 | < 0.001 |

| IIEF-5 | 0.396 | < 0.001 |

| SLQQ-QOL | 0.390 | < 0.001 |

| General health status of QLQ-C30 | 0.460 | < 0.001 |

We conducted univariate and multivariate analyses of factors influencing resilience in patients with PC. Both analyses revealed educational and per capita monthly household income levels as significant factors affecting the resilience of patients with PC (P < 0.05) (Tables 2 and 3).

| Variable | Group A (n = 69) | Group B (n = 78) | χ2 | P value |

| Age (years) | 0.080 | 0.777 | ||

| < 60 | 32 (46.38) | 38 (48.72) | ||

| ≥ 60 | 37 (53.62) | 40 (51.28) | ||

| Marital status | 0.162 | 0.687 | ||

| Married | 49 (71.01) | 53 (67.95) | ||

| Single | 20 (28.99) | 25 (32.05) | ||

| Children | 0.210 | 0.646 | ||

| Have | 51 (73.91) | 55 (70.51) | ||

| Don’t have | 18 (26.09) | 23 (29.49) | ||

| Education level | 4.561 | 0.033 | ||

| Below senior high school | 34 (49.28) | 52 (66.67) | ||

| Senior high school or above | 35 (50.72) | 26 (33.33) | ||

| Per capita monthly household income (CNY) | 4.871 | 0.027 | ||

| < 5000 | 29 (42.03) | 47 (60.26) | ||

| ≥ 5000 | 40 (57.97) | 31 (39.74) |

| Factor | β | SE | Wald | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Age (years) | -0.127 | 0.345 | 0.137 | 0.711 | 0.880 | 0.448-1.730 |

| Marital status | 0.084 | 0.375 | 0.050 | 0.822 | 1.088 | 0.521-2.271 |

| Children | 0.131 | 0.385 | 0.116 | 0.733 | 1.140 | 0.537-2.423 |

| Education level | 0.761 | 0.348 | 4.793 | 0.029 | 2.141 | 1.083-4.234 |

| Per capita monthly household income (CNY) | 0.764 | 0.346 | 4.882 | 0.027 | 2.147 | 1.090-4.230 |

PC is a male-related malignancy that causes a relatively high mortality risk, which is associated with the fact that patients are frequently in an advanced disease stage when diagnosed[17]. Currently, several relevant studies focus on the resilience of patients with PC; however, the majority of them focus on the potential associations or interactions between resilience and cancer treatment, psychosocial outcomes, sleep deterioration-related depression, family functioning, and self-efficacy[18-21]. Further investigations are warranted to assess the correlation of resilience with anxiety and dep

In this investigation, group A is considered a cohort with relatively increased resilience, whereas group B is a group with comparatively decreased resilience. Our data indicate that the group with higher resilience not only demon

Subsequently, the correlation analysis has robustly revealed the presence of a marked inverse association of resilience with anxiety and depression in patients with PC as well as a significant positive association with the two sexual function scales and quality of life. This indicates that resilience is not only closely associated with negative emotions but may also influence patients’ sexual function and quality of life levels. A 5-year study has further substantiated that resilience in patients with PC not only demonstrates a significant negative correlation with depression but also exhibits a significant protective effect against depression that varies over time, peaking at 6 months, 24 months, and 60 months[25]. Martin et al[26] reported a significant negative correlation between resilience and anxiety (r = -0.45, P < 0.001) as well as depression (r = -0.54, P < 0.001) in patients with PC, similar to our results. Generally, the anxiety and depression of patients with PC primarily originate from concerns about treatment side effects, such as urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction, along with the threat of tumor metastasis and death[27]. Patients with higher resilience typically carry less psychological burden and can more relatively face various possible stress events, with a positive and optimistic attitude and a relatively higher hope level[28].

Finally, we verified the factors influencing resilience in patients with PC. Both univariate and multivariate analyses reveal educational and per capita monthly household income levels as independent factors associated with resilience in patients with PC. Chien et al[29] revealed that psychological resilience in patients with PC has been significantly influenced by cancer-specific self-efficacy, with increased self-efficacy contributing to improved resilience. Furthermore, other studies have determined high perceived stress as a crucial predictor of psychological resilience in patients with PC, demonstrating a strong correlation with worsened emotional states and diminished quality of life[13].

This study has several limitations that warrant further refinement in future investigations. First, the cohort comprised only 147 PC patients from a single institution, lacking diversity in terms of geographic distribution, socioeconomic status, or disease phases (e.g., initial diagnosis vs recurrent/metastatic disease), potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study design only demonstrates an association between resilience and anxiety/depression, precluding causal inferences. Lastly, critical factors such as clinical variables (e.g., tumor stage, treatment modalities like surgery or endocrine therapy) and social support systems (e.g., family dynamics, physician-patient communication) were not comprehensively assessed for their influence on resilience, possibly resulting in overlooked confounders in the regression model. Future directions will involve expanding the study population to ensure heterogeneity, implementing longitudinal designs, and rigorously controlling for key confounding variables to enhance the robustness of this research.

In summary, a relatively high resilience in patients with PC is typically closely associated with relatively milder anxiety and depression as well as relatively higher sexual function and quality of life. Conversely, educational and per capita monthly household income levels may, to a certain extent, influence the resilience of patients with PC. Specifically, patients with PC with higher educational and per capita monthly household income levels demonstrated greater resilience.

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 55842] [Article Influence: 7977.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (132)] |

| 2. | Barsouk A, Padala SA, Vakiti A, Mohammed A, Saginala K, Thandra KC, Rawla P, Barsouk A. Epidemiology, Staging and Management of Prostate Cancer. Med Sci (Basel). 2020;8:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rawla P. Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World J Oncol. 2019;10:63-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 817] [Cited by in RCA: 1613] [Article Influence: 268.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Berenguer CV, Pereira F, Câmara JS, Pereira JAM. Underlying Features of Prostate Cancer-Statistics, Risk Factors, and Emerging Methods for Its Diagnosis. Curr Oncol. 2023;30:2300-2321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mitchell E, Ziegler E. Sexual Dysfunction in Gay and Bisexual Prostate Cancer Survivors: A Concept Analysis. J Homosex. 2022;69:1119-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Alvisi MF, Dordoni P, Rancati T, Avuzzi B, Nicolai N, Badenchini F, De Luca L, Magnani T, Marenghi C, Menichetti J, Silvia V, Fabiana Z, Roberto S, Riccardo V, Lara B; Prostate Cancer Multidisciplinary Clinic Working Group. Supporting Patients With Untreated Prostate Cancer on Active Surveillance: What Causes an Increase in Anxiety During the First 10 Months? Front Psychol. 2020;11:576459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pan S, Wang L, Zheng L, Luo J, Mao J, Qiao W, Zhu B, Wang W. Effects of stigma, anxiety and depression, and uncertainty in illness on quality of life in patients with prostate cancer: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Psychol. 2023;11:129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Brunckhorst O, Hashemi S, Martin A, George G, Van Hemelrijck M, Dasgupta P, Stewart R, Ahmed K. Depression, anxiety, and suicidality in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2021;24:281-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Carlsson S, Sandin F, Fall K, Lambe M, Adolfsson J, Stattin P, Bill-Axelson A. Risk of suicide in men with low-risk prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1588-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Maguire R, Drummond FJ, Hanly P, Gavin A, Sharp L. Problems sleeping with prostate cancer: exploring possible risk factors for sleep disturbance in a population-based sample of survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:3365-3373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Denckla CA, Cicchetti D, Kubzansky LD, Seedat S, Teicher MH, Williams DR, Koenen KC. Psychological resilience: an update on definitions, a critical appraisal, and research recommendations. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2020;11:1822064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sharpley CF, Arnold WM, Christie DRH, Bitsika V. Network connectivity between psychological resilience and depression in prostate cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2024;33:e6266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Groarke A, Curtis R, Skelton J, Groarke JM. Quality of life and adjustment in men with prostate cancer: Interplay of stress, threat and resilience. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0239469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Karoly P, Ruehlman LS. Psychological "resilience" and its correlates in chronic pain: findings from a national community sample. Pain. 2006;123:90-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bonanno GA, Galea S, Bucciarelli A, Vlahov D. What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:671-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 722] [Cited by in RCA: 579] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Killgore WDS, Taylor EC, Cloonan SA, Dailey NS. Psychological resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 66.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sekhoacha M, Riet K, Motloung P, Gumenku L, Adegoke A, Mashele S. Prostate Cancer Review: Genetics, Diagnosis, Treatment Options, and Alternative Approaches. Molecules. 2022;27:5730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 133.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sharpley CF, Christie DRH, Bitsika V. 'Steeling' effects in the association between psychological resilience and cancer treatment in prostate cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2021;30:67-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Christie DRH, Sharpley CF, Bitsika V. A Systematic Review of the Association between Psychological Resilience and Improved Psychosocial Outcomes in Prostate Cancer Patients: Could Resilience Training Have a Potential Role? World J Mens Health. 2025;43:70-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sharpley CF, Christie DRH, Bitsika V. Which Aspects of Psychological Resilience Moderate the Association between Deterioration in Sleep and Depression in Patients with Prostate Cancer? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:8505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhou Y, Shan H, Wu C, Chen H, Shen Y, Shi W, Wang L, Li Q. The mediating effect of self-efficacy on family functioning and psychological resilience in prostate cancer patients. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1392167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sharpley CF, Christie DRH, Bitsika V, Andronicos NM, Agnew LL, Richards TM, McMillan ME. Comparing a genetic and a psychological factor as correlates of anxiety, depression, and chronic stress in men with prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:3195-3200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhao X, Sun M, Yang Y. Effects of social support, hope and resilience on depressive symptoms within 18 months after diagnosis of prostate cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sharpley CF, Bitsika V, Wootten AC, Christie DR. Does resilience 'buffer' against depression in prostate cancer patients? A multi-site replication study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2014;23:545-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sharpley CF, Wootten AC, Bitsika V, Christie DR. Variability over time-since- diagnosis in the protective effect of psychological resilience against depression in Australian prostate cancer patients: implications for patient treatment models. Am J Mens Health. 2013;7:414-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Martin CM, Schofield E, Napolitano S, Avildsen IK, Emanu JC, Tutino R, Roth AJ, Nelson CJ. African-centered coping, resilience, and psychological distress in Black prostate cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2022;31:622-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nelson CJ, Balk EM, Roth AJ. Distress, anxiety, depression, and emotional well-being in African-American men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1052-1060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Scandurra C, Mangiapia F, La Rocca R, Di Bello F, De Lucia N, Muzii B, Cantone M, Zampi R, Califano G, Maldonato NM, Longo N. A cross-sectional study on demoralization in prostate cancer patients: the role of masculine self-esteem, depression, and resilience. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:7021-7030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chien CH, Pang ST, Chuang CK, Liu KL, Wu CT, Yu KJ, Huang XY, Lin PH. Exploring psychological resilience and demoralisation in prostate cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2022;31:e13759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |