Published online May 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i5.103937

Revised: February 5, 2025

Accepted: March 21, 2025

Published online: May 19, 2025

Processing time: 131 Days and 1.3 Hours

Depression is a widespread psychological disorder that has substantial effects on public health and society. Conventional therapies include medication and psychotherapy, recent investigations have highlighted the possible advantages of multi

To perform a meta-analysis of how multimodal physical therapy can help treat depression.

We searched for collection of articles that satisfied the inclusion and exclusion criteria, encompassing randomized controlled research-related sources. We incorporated these studies into the meta-analysis using terms such as “findings”, “intervention”, and “population attributes”. We used statistical examination to measure the total impact magnitude and evaluate study variability.

The encouraging aspect is that multi-modal physical therapy is being considered for its effectiveness in treating symptoms related to depression. Sensitivity analysis was conducted to identify key factors and determine their impact on quality.

Regarding treatment for depression, this meta-analysis extends the increasing number of studies demonstrating the effectiveness of multimodal physical therapy.

Core Tip: This meta-analysis confirms the effectiveness of multimodal physical therapy in alleviating depressive symptoms. Multimodal physical therapy, which combines exercise with various complementary treatments, is believed to effectively reduce depressive symptoms by enhancing both physical health and psychological well-being. By combining various therapeutic approaches, it demonstrates significant potential benefits; however, sensitivity analyses highlight the necessity for additional high-quality research to strengthen the evidence.

- Citation: Sun B, Li C, Zhang CL, Li JH, Mao M, Wang G, Zhang ZF. Meta-analysis of the effects of multimodal physical therapy on improving depression. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(5): 103937

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i5/103937.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i5.103937

A statistical technique called meta-evaluation is used to combine findings from several research on a certain topic in order to provide more thorough information on the overall impact. In the context of physical therapy for treating depression, multimodal physical therapy refers to interventions that integrate diverse physical techniques such as workouts, massage, and other modalities with mental health counseling[1]. This method aims to address the physical and mental aspects of depression simultaneously. Several meta-analyses have explored the outcomes of multimodal physical therapy on depression[2]. To evaluate the efficacy of these therapies across a range of groups and situations, research usually combines data from sophisticated investigations and randomized controlled trials. Meta-analytic critiques are valuable because they can identify styles and traits that character studies might not encounter due to differences in sample sizes or methodologies[3].

The primary goal of multimodal physical therapy in treating depression is to harness the benefits of physical activity on emotional health. In particular, exercise has been studied for its antidepressant effects, which are attributed to mechanisms such as multiplied endorphin manufacturing, improved neuroplasticity, and reduced oxidative stress[4]. Combining exercise with different modalities such as cognitive-behavioral techniques or mindfulness practices can enhance typical treatment results.

Meta-analyses regularly identify moderators and mediators of treatment outcomes[5]. These can encompass elements such as the intensity and duration of therapy, affected therapy adherence, therapist competence, and particular traits of the determined samples. Understanding those nuances allows clinicians and researchers to refine treatment protocols and determine which affected populations might gain the maximum benefits from multimodal physical therapy[6]. It also investigates the quality of evidence across the included studies.

The findings of meta-analyses have suggested that multimodal physical therapy can effectively reduce depressive symptoms. For example, a meta-analysis published in an outstanding psychology journal synthesized data from more than one randomized controlled trial and determined that multimodal interventions notably reduced depression severity compared to manipulated situations[7]. This reduction in symptoms was observed across various age groups and study populations, indicating the wide applicability of such treatments.

Meta-analyses have provided compelling proof that multi-model physical therapy is a promising method for enhancing treatment effects for depression. By integrating diverse physical and mental interventions, these therapies capitalize on the synergistic effects of multiple treatment modalities[8]. Continued research and refinement of these approaches are vital for optimizing healing methods and improving the cognitive well-being outcomes for individuals suffering from depression[9].

The search strategy and methodology were designed to yield a wide variety of research for in-depth analysis. No formal review protocol was referenced, as the search was designed to ensure comprehensive coverage of the available literature.

Only a few studies investigating the effects of physical exercise treatments on the severity of depressive symptoms in adolescents were found in a prior review[10]. Therefore, the eligibility requirements for this review were quite wide to collect a sufficient number of research papers for meta-and subset analyses.

Population size: Studies that enrolled individuals diagnosed with depression at the beginning and had an average participation age were appropriate for this evaluation. During structured medical interviews, the initial depressive symptoms of participants had to be identified using a positive minimum standard based on precise self-assessment scales or established scientific requirements. Studies involving patients with comorbid conditions, such as obesity, diabetes, and cancer, were excluded from this analysis.

Interventions: Studies were included that examined the effects of a physical activity regimen affected depressive symptoms. Any physical activity intervention that met this definition satisfied the treatment inclusion requirements of the overview[11].

Comparisons: Studies comparing the effects of exercise on control groups were eligible for this analysis. This review investigated alternative or supplementary physical exercise treatments for depression. Therefore, studies involving adolescents in the control group that utilized guideline-recommended treatments, such as medication and psychotherapy, for depression were excluded. This restriction was implemented to investigate the potential links between the physio

Outcomes: Studies were included in this analysis on the condition that they employed a continuous measure to evaluate the severity of participants’ depressive symptoms following the intervention. Since the core aim of this review was to determine the intensity of depressive symptoms, the inclusion of a continuous symptom measure was mandatory for studies to be considered eligible.

Design: We used randomized controlled studies (including cluster randomized controlled trials) in this analysis.

The search phrases selected were intended to yield a wide variety of research for in-depth analysis. To locate relevant research in PubMed and Web pages, we employed the following search algorithm: Adolescents [Abstract/Title] Puberty OR [Title/Abstract] OR [Title/Abstract] OR girl Instead of boy* [Title/Abstract] AND (workout) [Abstract/Title] OR sport*[Abstract/Title] (Depressed) [Abstract/Title] OR “emotional symptom*”[Abstract/Title] Conversely, “emotional disorder” [Abstract/Title] OR “psychological disorder” [Abstract/Title]). We also searched using the following terms: “training through physical means” [Abstract/Title] OR “physical activity” [Abstract/Title] OR “physical effort” [Abstract/Title] It might also be “physical education” [Title/Abstract] OR in operation [Title/Abstract] OR operating [Title/Abstract] OR walking [Title/Abstract] OR cycling [Title/Abstract] OR “traits for strengthening” [Title/Abstract] or swimming [Abstract/Title]. A thorough search strategy was used in this investigation.

Using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, we assessed the degree of confidence in the evidence included in the initial meta-analysis[12]. The GRADE system uses four categories to classify the level of confidence: Highest, average, lowest, and extremely low. Confidence in the evidence is diminished if there are one or more of the following issues: Limitations in study design, inconsistencies, indirectness, inaccuracies, and publication bias. One member of the review team provided the GRADE ratings for all reviewed studies[13].

We examined the antidepressant properties of physical activity therapies mediated by either the methodological components of previous studies or the methods used for physical activity therapies. In this section, we describe the methodology for categorizing effect size estimates into subgroups to assess the influence of moderators based on the studies included in our analysis.

Method of diagnosis for initial depression identification: Based on the research, we used the results of a self-evaluation scale or organized clinical conversations to identify symptoms of depression in adolescents. Initially, we conducted a subgroup analysis to further investigate these symptoms.

Type of experimental group: We performed a subgroup assessment depending on whether the study used an active or passive test group. Participants were classified as active if the physical activity group received psychological stimulation comparable to that of the simulated therapy group, and the untreated group was administered a placebo that did not lead to a significant improvement in cardiovascular fitness. If the members of the study group were not exposed to such experimental manipulations, they were categorized as passive participants.

Type of exercise: We conducted a subgroup evaluation considering whether the various exercise regimens were either standardized or game-based.

Energy levels: We performed a subgroup analysis based on whether the studies included minimal, moderate, or robust intensive physical activity. The recommendations were followed for operationalizing sessions of physical exercise at low, moderate, or high intensity. Current standards recommend that teenagers participate in moderate-to-intense physical exercise for a minimum of 60 minutes each day. We also combined medium- and high-intensity physical activity and compared it with moderately strenuous activity to determine whether the antidepressant advantages of medium-to-severe exercise outweigh those of low-energy activity.

Environment: We performed a subgroups analysis based on whether the study participants received supplementary psychiatric therapies, medication, or control treatment in addition to taking part in physical activity.

Duration of therapy with physical activity: The frequency of weekly workouts, the length of each workout, the number of weeks of intervention, and the overall duration of the exercise therapy were all examined using meta-regression to determine their temporal components and their potential to affect results.

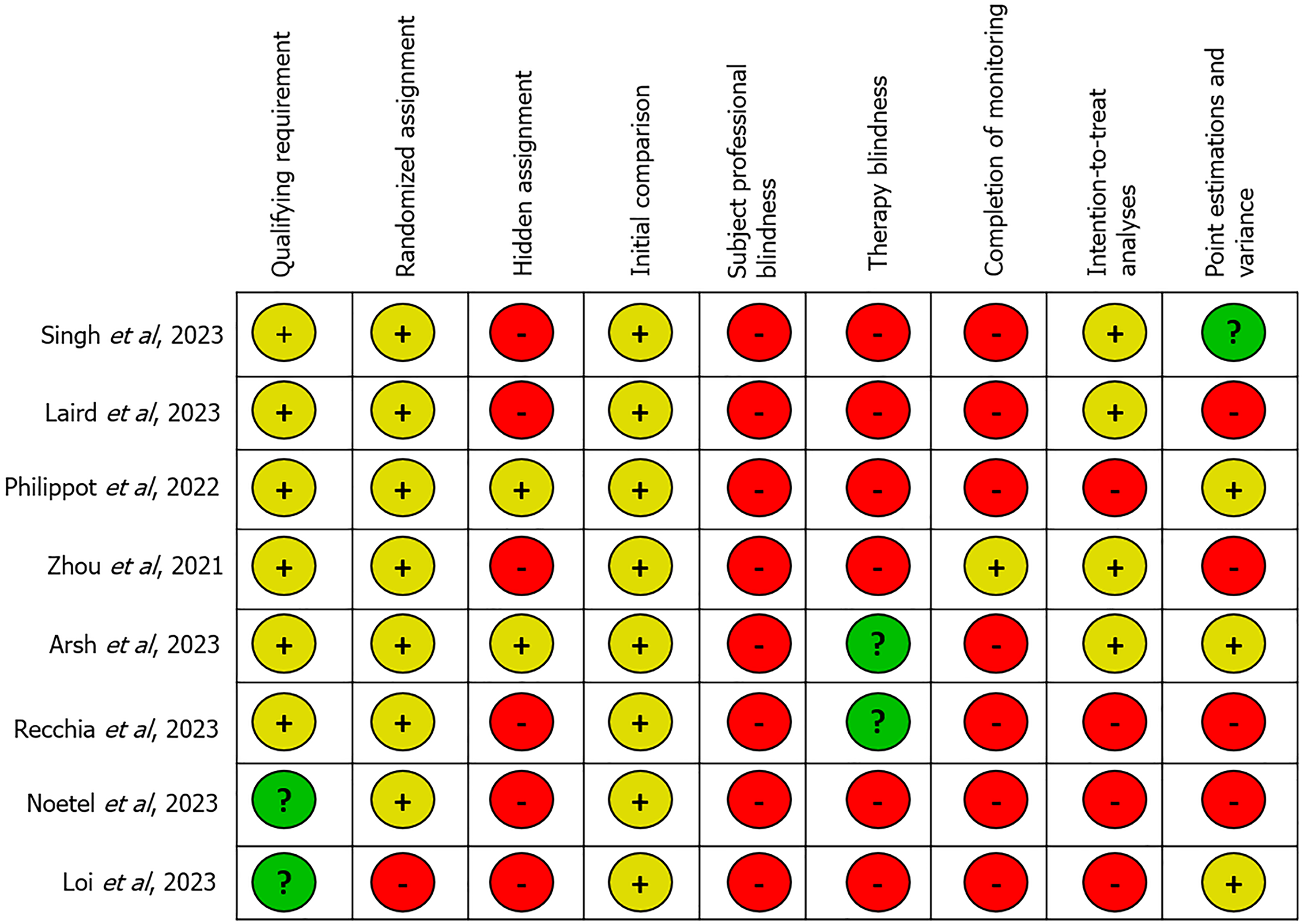

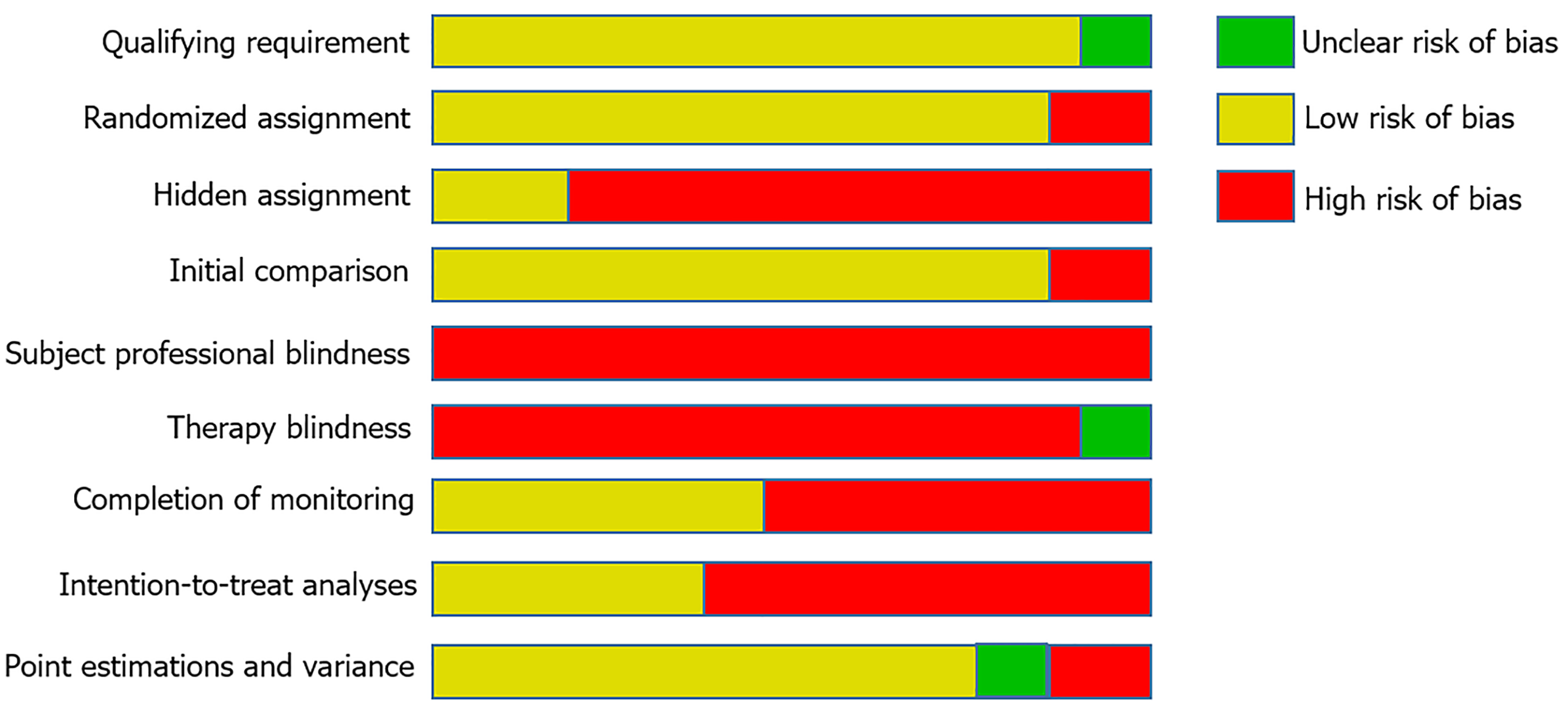

The potential for bias in the included studies was assessed using the physical therapy evidence databases (PEDro) assessment system. The PEDro rating system comprises the following nine items: Experts rated each of the nine included studies. If the study’s complete text made it apparent that the conditions of each item had been fulfilled, it was assigned a low probability of bias. We classified a study having a significant possibility of bias if the full-text publication did not explicitly state that the standards were met. The experts evaluated the included studies using the PEDro magnitude scale.

We retrieved data on the type of release, methodology, population characteristics, outcome measures, treatment details, and control group details following the intervention. Data were also included on measurements and assessment duration following the conclusion of treatment[14]. If a publication lacked sufficient details for study evaluation or presented data exclusively in graphical form, we contacted the study’s authors to request additional information. Data were merged according to the described processes if an encompassed study examined the impact of multiple exercise medications with a test group, and if those exercise therapies were comparable in terms of the moderating influences investigated in this study.

The main meta-analysis investigated how physical activity interventions affect the intensity of depressive symptoms in adolescents. This was accomplished by computing the bias-adjusted Hedges’g standardized mean deviation (SMD) for each study between the physical activity and control groups post-intervention. The aggregated SMD size was interpreted according to Cohen’s classification. SMD values were considered to represent modest, moderate, and high impact sizes. To enhance comprehension, the pooled SMD was also converted into Beck Depression Inventory scores.

Physical activity has an antidepressant effect when expressed by negative SMD values. By computing Higgins’ statistic, we quantified study inconsistencies. The Higgins’ values were considered to represent a small, moderate, or substantial amount of between-study variability.

Using meta-regression and subgroup analyses, we investigated the potential moderating effects of the identified factors[15]. In each included trial, the variance in dropout rates between the exercise and control groups served as a proxy for assessing treatment feasibility. The Mantel-Haenszel method was used to pool the risk-difference data by incorporating random effects.

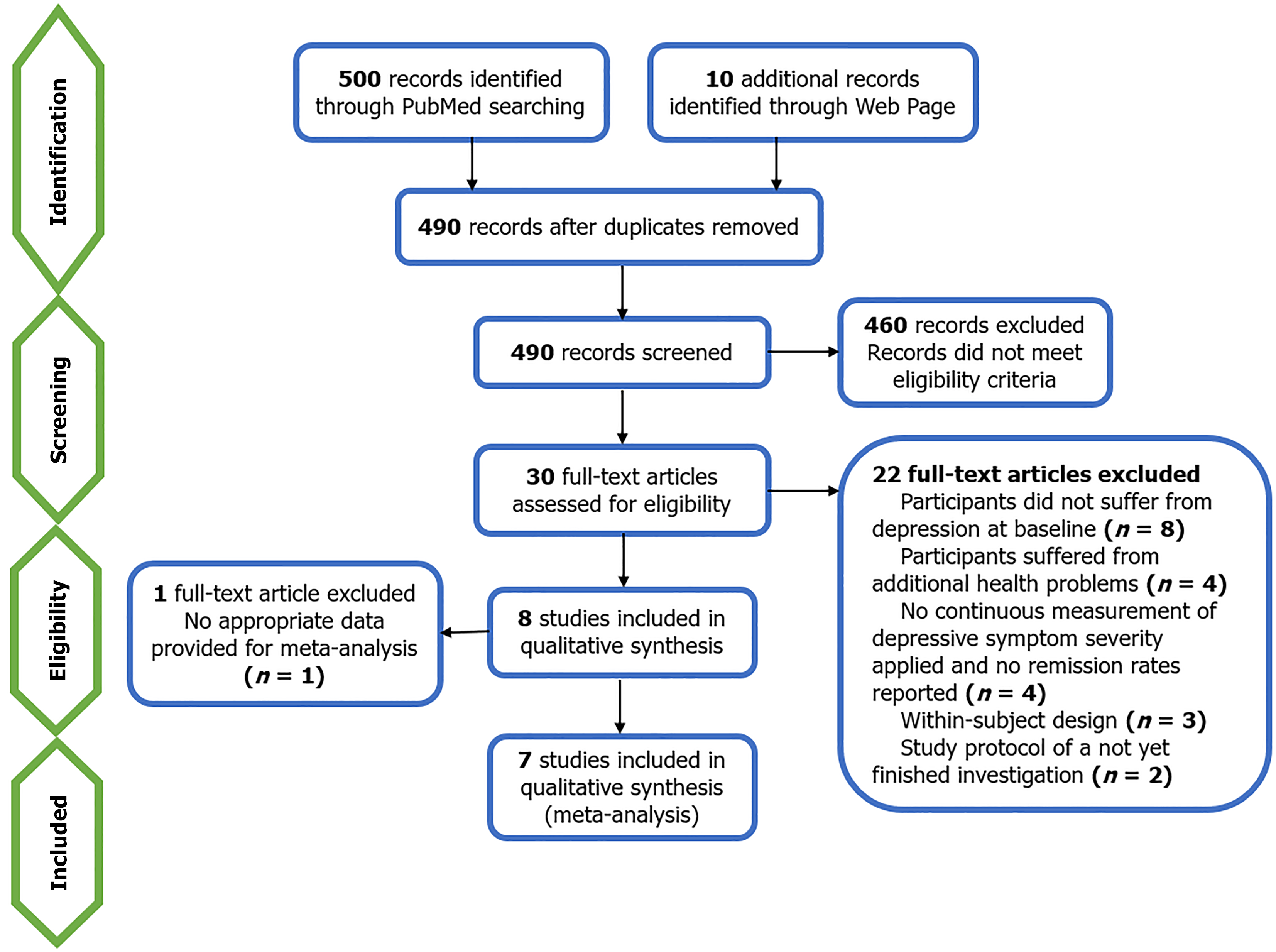

The PRISMA diagram in Figure 1 summarizes the selection procedure. Eight studies were ultimately identified and incorporated into the subjective summary of this study. Nevertheless, one of the eight studies lacked the necessary data for a meta-analysis, and the author of that study declined to respond to our request for data. As a result, seven studies that included information from 400 adolescents with depression were included in the main meta-analysis.

The features of the investigations comprising this review’s quantitative synthesis are presented in Table 1[16-23]. The eight studies that comprised the qualitative evaluation included 491 individuals with depression. The sample sizes varied from 24 to 100. Only female participants were enrolled in two studies, whereas only male participants were enrolled in one study. The only depression treatment administered to participants in six of the eight studies was physical activity. These studies were conducted in educational settings. In the remaining four studies, individuals received physical therapy in addition to psychological treatment and medication. The types of physical activity used in the investigations differed greatly. An ergometer was used for three studies that implemented a cycling intervention. Three studies used sports-related activities including volleyball, badminton, and football. Walk/run methods were used in two studies.

| Ref. | Study format | Sample | Measurement | Results |

| Singh et al[16] | Randomized controlled trial | 128119 participants | Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale | For a wide variety of adults, including the general population, individuals with documented psychological disorders, and those with chronic illnesses, physical activity was very useful for reducing symptoms of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress |

| Laird et al[17] | Randomized controlled trial | 4016 individuals | Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale | Investigated whether in older adults with and without chronic illnesses if achieving lower physical activity thresholds could be helpful for public health programs aimed at lowering the incidence of depression |

| Philippot et al[18] | Randomized controlled trial | 52 adolescent patients | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | The effectiveness of that treatment method has been demonstrated by the reduction in depressed symptoms displayed by teenage patients with depression who undergo organized workout as an additional treatment as part of their overall psychological care |

| Zhou et al[19] | Randomized, placebo-controlled, and double-blinded trial | 84 patients | Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale | According to the experiment, promethazine administered intraoperatively can help neurosurgery patients who have moderate-to-severe depression symptoms without compromising safety |

| Arsh et al[20] | Randomized controlled trial | 1363 patients | Hamilton Depression Scale | While exercise can successfully lessen the intensity of depression symptoms, it does not appear to have a significant impact on glycemic management |

| Recchia et al[21] | Randomized controlled trial | 2441 participants | Validated depression scales | In young people and adolescents, physical activity therapies can be utilized to lessen depressive symptoms |

| Noetel et al[22] | Randomized controlled trial | 14170 participants | Beck Depression Inventory, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale | Assurance for jogging or walking was inadequate, and it was extremely low for additional therapies |

| Loi et al[23] | Randomized controlled trial | 212 patients | Geriatric Depression Scale-15 | For care givers of individuals with dementia, a physical activity intervention might not be as helpful in reducing signs of depression as it would be for other types of caretakers |

Each included study explained how participants were recruited and whether they met the eligibility requirements. Out of 36 studies with full-text available that were assessed for eligibility, 22 studies were excluded not suffering, additional health problems, and no measurements. Subsequently, ten studies were included for further review. One study lacked point estimates, variance measurements, and between-group assessments. The risk of bias each study is shown in Figure 2, while the risk of bias in various types of research is shown in Figure 3. Therapists and participants were not blinded in any of the included investigations.

In this section, we explain how the impact size estimates from the included studies were divided into subgroups.

Method of diagnosis for initial depression identification: Collectively, information from research utilizing a structured clinical interview process to identify depression at baseline revealed a significant effect. A small-to-moderate effect was observed when data from trials that used a self-report scale for the initial diagnosis of depression were combined. The impact sizes in each of these categories did not differ significantly.

Type of testing group: A modest antidepressant effect was noted upon pooling data from studies that compared physical activity with a physically active control group. A moderate-to-large impact of antidepressants was obtained by combining data from trials that included a passive control group. Table 2 shows the results of the moderator evaluation of the procedural characteristics.

| Procedural characteristics | Number of participants | Impact size estimates | 95%CI | SMD | P values | Variability | Meta-regression |

| Method of initial depression diagnosis | |||||||

| Organized clinical conversation | 112 | 6 | -2.23 to -0.53 | -0.92 | P = 0.0003 | Q = 4.16, P = 0.4, df = 2, T2 = 0, I2 = 0% | Q-between = 4.43, df = 1, P = 0.1 |

| Self-report scale | 335 | 9 | -0.81 to -0.53 | -0.54 | P = 0.0019 | Q = 12.18, P = 0.11, df = 9, T2 = 0.0025, I2 = 34.9% | |

| Type of testing group | |||||||

| Active group | 130 | 8 | -0.85 to 0.33 | -0.47 | P = 0.1674 | Q = 3.73, P = 0.62, df = 6, T2 = 0, I2 = 0% | Q-between = 3.72, df = 1, P = 0.19 |

| Passive group | 315 | 10 | -0.94 to -0.45 | -0.79 | P = 0.006 | Q = 13.55, P = 0.04, df = 8, T2 = 0.0804, I2 = 51.8% | |

Type of exercise: A subgroup evaluation showed approximately the same magnitude of effects between examiners applying an established exercise treatment without sports characteristics and examiners using game-based physical activity.

Energy levels: A subgroup evaluation showed statistically significant variance in the accumulated effect, including physical activity at low, medium, and high intensities. When small-scale physical activity studies were combined, the overall effect size was low. After combining information from trials that employing moderate levels of exercise, a significant impact size was found. When data from research using intense physical activity interventions were included, the impact magnitude was high.

Environment: Subgroup analysis revealed a small-to-moderate effect size of antidepressants, derived from studies that incorporated physical activity or control group treatments in conjunction with psychological interventions and/or medication within a clinical context. The pooled effect size of studies exclusively examining physical exercise and an educational setting as a no-treatment control group therapy was found to be medium to large. No statistically significant differences in impact sizes were observed across the groupings.

Duration of therapy with physical activity: The meta-regression analysis results showed no connection between any component related to the length of the exercise sessions and the effects of antidepressants (session duration, weekly session count, total number of weeks, and overall extent). Table 3 presents the results of the moderator analysis on physical activity characteristics.

| Physical activity characteristics | Number of participants | Impact size estimates | 95%CI | SMD | P values | Variability | Meta-regression |

| Type of exercise | |||||||

| Exercise treatment without sports | 287 | 11 | -0. 94 to -0.25 | -0.65 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.24, df = 10, Q = 9.34, T2 = 0.0317, I2 = 8.5% | Between Q = 0, P = 0.01, df = 1 |

| Game-based physical activity | 195 | 5 | -0.204 to -0.21 | -0.67 | P = 0.1015 | P = 0.02, df = 4, Q = 8.64, T2 = 0.1565, I2 = 70.9% | |

| Energy levels | |||||||

| Low | 145 | 5 | -0.56 to 0.34 | -0.09 | P = 0.5455 | P = 0.95, Q = 0.46, df = 1, T2 = 0, I2 = 0% | Between Q = 7.72, P = 0.02, df = 1 |

| Medium | 185 | 6 | -0.37 to -0.56 | -0.96 | P = 0.0002 | Q = 5.7, P = 0.20, df = 2, T2 = 0.0745, I2 = 34.9% | |

| High | 135 | 6 | -0.96 to -0.23 | -0.74 | P = 0.0056 | Q = 3.23, P = 0.65, df = 5, T2 = 0, I2 = 0% | |

| Environment | |||||||

| Physical exercise and educational atmosphere | 201 | 8 | -0.87 to -0.07 | -0.58 | P = 0.0157 | Q = 4.14, P = 0.75, df = 6, T2 = 0, I2 = 0% | Between Q = 0.95, P = 0.29, df = 1 |

| Physical activity | 245 | 8 | -3.03 to -0.18 | -0.74 | P = 0.00475 | Q = 13.45, P = 0.03, df = 6, T2 = 0.1423, I2 = 67.3% | |

| Duration of therapy with physical activity | |||||||

| Session duration | - | - | - | - | - | - | Q-balance = 0.46, P = 0.36, df = 1, R2 = 0% |

| Weekly session count | - | - | - | - | - | - | Q-balance = 0.06, P = 0.65, df = 1, R2 = 0% |

| Total number of weeks | - | - | - | - | - | - | Q-balance = 0.44, P = 0.53, df = 1, R2 = 0% |

| Total duration | - | - | - | - | - | - | Q-balance = 0.001, P = 0.01, df = 1, R2 = 0% |

Out of the ten studies included in this analysis, only two assessed the dropout rate to assess the depression medication benefits of exercise treatment among adolescents with depression. The recovery rate data from the two studies were not evaluated quantitatively because the statistical power was insufficient[24]. Here, we present the findings from the two trials that provided qualitative information on remission rates. After treatment, remission was achieved in 31% of those enrolled in the control group, 50% of those in the whole-body vibration exercise group[25].

Each study subjected to quantitative evaluation disclosed treatment discontinuation. The physical exercise group had an average departure rate of 9.01% [95% confidence interval (CI): 8.06-10.96]. The median departure rate in the control groups was 13.49% (95%CI: 11.37-14.6). Between the exercise and control groups, we could not find significant variance in the risk of dropout (k = 11, RD = -0.04, 95%CI: -0.09 to 0.04, P = 0.30).

The examination of the literature primarily shows the alleviation of symptoms of depression through physical activity among adolescents. It is also well supported by the evidence regarding exercise in relation to the alleviation of depressive symptoms, especially in conjunction with psychological interventions or medication. According to the investigation, sports and organized exercise programs are two examples of physical activities that have been shown to be beneficial for mental health. Subgroup evaluations revealed that moderate-intensity physical activity had the most significant impact. However, the duration of therapy did not show a clear correlation with the treatment outcomes. The risk of bias in studies was notable, especially due to lack of blinding. The evidence suggests that healthcare providers should consider incorporating physical activity into treatment plans for adolescents with depression. The findings are relevant for users, as they demonstrate that physical activity can serve as a beneficial complementary treatment. These findings highlight the significance of supporting physical activity programs in mental health efforts for policymakers. Although more research is required to improve and optimize its application, the review’s overall findings indicate that physical exercise is a viable strategy for controlling teenage depression. This meta-analysis has some limitations affecting causal inference. First, significant heterogeneity in intervention protocols (e.g., exercise types, intensities, adjunct therapies) complicates attributing observed effects to specific components of multimodal physical therapy. Second, residual confounding from unmeasured variables (e.g., lifestyle factors, genetic predispositions) may bias outcomes despite randomized designs, undermining causal conclusions. Third, short follow-up periods in included studies restrict insights into long-term causal relationships between interventions and sustained depression reduction. While blinding challenges and publication bias also pose concerns, these three limitations most directly impact the validity of causal claims. Future research should prioritize standardized interventions, rigorous control of confounders, and extended follow-ups to strengthen causal inferences.

Multimodal physical therapy, integrating exercise with other therapies, is considered to help alleviate depressive symptoms through improvements in both physical and mental conditions. This option offers a supplementary route of treatment, alongside the standard methods of drug and psychotherapy. According to the findings of this meta-analysis, physical activity therapy can be useful as an alternative form of therapy for adolescents with depression to reduce the intensity of their symptoms. Nevertheless, caution should be used when interpreting these findings. The level of certainty in the evidence was limited because of concerns regarding the methodology and accuracy of the research. Key limitations include heterogeneity in intervention protocols (e.g., variations in exercise types, intensities, and adjunct therapies), which complicates causal attribution to specific components; residual confounding from unmeasured variables (e.g., lifestyle factors, genetic predispositions) that may bias outcomes despite randomized designs; and short follow-up durations in included studies, limiting insights into long-term efficacy. According to moderator analyses, adolescents with depression should engage in moderate physical exercise to reduce their symptoms. The research also highlights the need for stan

To further advance the understanding of multimodal physical therapy in depression management, future studies should prioritize longitudinal designs to evaluate sustained effects. Prospective cohort studies, such as those that track participants over extended periods, are suggested to better reveal the long-term effects of multimodal physical therapy on depression. These studies could capture fluctuations in depressive symptoms, adherence to physical activity regimens, and interactions with concurrent treatments (e.g., pharmacotherapy). Additionally, integrating biomarkers (e.g., inflammatory markers, neuroplasticity indices) and neuroimaging techniques may elucidate the biological pathways linking physical activity to emotional health. For example, multimodal neuroimaging techniques have been used to study the relationship between neurotransmitter function and symptoms in movement disorders, which could provide insights into similar mechanisms in depression. Research should also explore optimal intervention protocols, such as dose-response relationships, modality combinations, and personalized approaches, to maximize efficacy. Comparative effectiveness trials could assess how multimodal physical therapy synergizes with emerging therapies like digital mental health tools. For instance, a recent study developed a multimodal digital measurement system to assess depression, demonstrating the potential of combining different digital modalities to improve detection and monitoring. Finally, expanding studies to underrepresented groups (e.g., individuals with comorbidities, varying socioeconomic backgrounds) and real-world clinical settings will enhance generalizability. Addressing these gaps will inform evidence-based guidelines and refine implementation strategies for integrating physical therapy into holistic depression care.

| 1. | Ho M, Ho JWC, Fong DYT, Lee CF, Macfarlane DJ, Cerin E, Lee AM, Leung S, Chan WYY, Leung IPF, Lam SHS, Chu N, Taylor AJ, Cheng KK. Effects of dietary and physical activity interventions on generic and cancer-specific health-related quality of life, anxiety, and depression in colorectal cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14:424-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bidzan-Wiącek M, Błażek M, Antosiewicz J. The relationship between physical activity and depressive symptoms in males: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2024;243:104145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fong Yan A, Nicholson LL, Ward RE, Hiller CE, Dovey K, Parker HM, Low LF, Moyle G, Chan C. The Effectiveness of Dance Interventions on Psychological and Cognitive Health Outcomes Compared with Other Forms of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2024;54:1179-1205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kerkez M, Erci B. The Effect of Moving Meditation Exercise on Depression and Sleep Quality of the Elderly: A Randomized Controlled Study. Holist Nurs Pract. 2024;38:41-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | He L, Soh KL, Huang F, Khaza'ai H, Geok SK, Vorasiha P, Chen A, Ma J. The impact of physical activity intervention on perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023;321:304-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liang J, Huang S, Jiang N, Kakaer A, Chen Y, Liu M, Pu Y, Huang S, Pu X, Zhao Y, Chen Y. Association Between Joint Physical Activity and Dietary Quality and Lower Risk of Depression Symptoms in US Adults: Cross-sectional NHANES Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2023;9:e45776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Soriano-Maldonado A, Díez-Fernández DM, Esteban-Simón A, Rodríguez-Pérez MA, Artés-Rodríguez E, Casimiro-Artés MA, Moreno-Martos H, Toro-de-Federico A, Hachem-Salas N, Bartholdy C, Henriksen M, Casimiro-Andújar AJ. Effects of a 12-week supervised resistance training program, combined with home-based physical activity, on physical fitness and quality of life in female breast cancer survivors: the EFICAN randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2023;17:1371-1385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nguyen PY, Astell-Burt T, Rahimi-Ardabili H, Feng X. Effect of nature prescriptions on cardiometabolic and mental health, and physical activity: a systematic review. Lancet Planet Health. 2023;7:e313-e328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gerber M, Cody R, Beck J, Brand S, Donath L, Eckert A, Faude O, Hatzinger M, Imboden C, Kreppke JN, Lang UE, Mans S, Mikoteit T, Oswald A, Schweinfurth-Keck N, Zahner L, Ludyga S. Differences in Selective Attention and Inhibitory Control in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder and Healthy Controls Who Do Not Engage in Sufficient Physical Activity. J Clin Med. 2023;12:3370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | von Zimmermann C, Winkelmann M, Richter-Schmidinger T, Mühle C, Kornhuber J, Lenz B. Physical Activity and Body Composition Are Associated With Severity and Risk of Depression, and Serum Lipids. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Herbert C, Meixner F, Wiebking C, Gilg V. Regular Physical Activity, Short-Term Exercise, Mental Health, and Well-Being Among University Students: The Results of an Online and a Laboratory Study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kandola A, Lewis G, Osborn DPJ, Stubbs B, Hayes JF. Depressive symptoms and objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behaviour throughout adolescence: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:262-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rethorst CD, Carmody TJ, Argenbright KE, Mayes TL, Hamann HA, Trivedi MH. Considering depression as a secondary outcome in the optimization of physical activity interventions for breast cancer survivors in the PACES trial: a factorial randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2023;20:47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Garcia A, Yáñez AM, Bennasar-Veny M, Navarro C, Salva J, Ibarra O, Gomez-Juanes R, Serrano-Ripoll MJ, Oliván B, Gili M, Roca M, Riera-Serra P, Aguilar-Latorre A, Montero-Marin J, Garcia-Toro M. Efficacy of an adjuvant non-face-to-face multimodal lifestyle modification program for patients with treatment-resistant major depression: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2023;319:114975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lange KW, Nakamura Y, Lange KM. Sport and exercise as medicine in the prevention and treatment of depression. Front Sports Act Living. 2023;5:1136314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Singh B, Olds T, Curtis R, Dumuid D, Virgara R, Watson A, Szeto K, O'Connor E, Ferguson T, Eglitis E, Miatke A, Simpson CE, Maher C. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: an overview of systematic reviews. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57:1203-1209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 163.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Laird E, Rasmussen CL, Kenny RA, Herring MP. Physical Activity Dose and Depression in a Cohort of Older Adults in The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2322489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Philippot A, Dubois V, Lambrechts K, Grogna D, Robert A, Jonckheer U, Chakib W, Beine A, Bleyenheuft Y, De Volder AG. Impact of physical exercise on depression and anxiety in adolescent inpatients: A randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2022;301:145-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhou Y, Sun W, Zhang G, Wang A, Lin S, Chan MTV, Peng Y, Wang G, Han R. Ketamine Alleviates Depressive Symptoms in Patients Undergoing Intracranial Tumor Resection: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesth Analg. 2021;133:1588-1597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Arsh A, Afaq S, Carswell C, Bhatti MM, Ullah I, Siddiqi N. Effectiveness of physical activity in managing co-morbid depression in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023;329:448-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Recchia F, Bernal JDK, Fong DY, Wong SHS, Chung PK, Chan DKC, Capio CM, Yu CCW, Wong SWS, Sit CHP, Chen YJ, Thompson WR, Siu PM. Physical Activity Interventions to Alleviate Depressive Symptoms in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177:132-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Noetel M, Sanders T, Gallardo-Gómez D, Taylor P, Del Pozo Cruz B, van den Hoek D, Smith JJ, Mahoney J, Spathis J, Moresi M, Pagano R, Pagano L, Vasconcellos R, Arnott H, Varley B, Parker P, Biddle S, Lonsdale C. Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2024;384:e075847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 132.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Loi SM, Gaffy E, Malta S, Russell MA, Williams S, Ames D, Hill KD, Batchelor F, Cyarto EV, Haines T, Lautenschlager NT, Mackenzie L, Moore KJ, Savvas SM, Dow B. Effects of physical activity on depressive symptoms in older caregivers: The IMPACCT randomized controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2024;39:e6058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Walter KH, Otis NP, Ray TN, Glassman LH, Beltran JL, Kobayashi Elliott KT, Michalewicz-Kragh B. A randomized controlled trial of surf and hike therapy for U.S. active duty service members with major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Blumenthal JA, Rozanski A. Exercise as a therapeutic modality for the prevention and treatment of depression. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2023;77:50-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |