Published online Jul 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i7.106281

Revised: April 28, 2025

Accepted: May 27, 2025

Published online: July 18, 2025

Processing time: 146 Days and 10.6 Hours

Truliant® posterior stabilized (PS) and Truliant cruciate retaining (CR) are two designs used for total knee arthroplasty. Survivorship and reason for revision rates are now available from the American Joint Replacement Registry (AJRR) at short-term time points for both Truliant designs. It was hypothesized that Truliant PS and Truliant CR perform comparably to similar designs in terms of survi

To analyze short-term survivorship of Truliant PS or CR total knee arthroplasty relative to non-Truliant PS or CR total knee arthroplasty.

Utilizing data from the AJRR, a retrospective review was performed for subjects who underwent implantation of Truliant PS, Truliant CR, non-Truliant PS, and non-Truliant CR designs as of June 30, 2022. Survivorship and reasons for revision were compared statistically between Truliant PS vs non-Truliant PS as well as Truliant CR vs non-Truliant CR groups. Cumulative percent revision rates were compared across three registries, AJRR, Australian Orthopaedic Association Na

Truliant PS survivorship was 97.95% at the four-year mark, while Truliant CR survivorship was 99.61% at the three-year mark. There were no significant dif

This study demonstrates high survivorship for Truliant PS total knee arthroplasty out to four-years and Truliant CR total knee arthroplasty out to three-years of follow-up.

Core Tip: Short-term data on the Truliant Total Knee System in the posterior stabilized design show it performs at least as well as the aggregate of all other posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasties performed and recorded in the American Joint Replacement Registry and Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry databases. For the Truliant cruciate retaining design, short-term data show it performs better than the aggregate of all other cruciate retaining total knee arthroplasties performed and recorded in the American Joint Replacement Registry, the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry, and the United Kingdom's National Joint Registry databases.

- Citation: Jones K, Muehlmann AM, Musgrave M, Penrose CT. Short-term survivorship of Truliant® total knee arthroplasty implants utilizing the American Joint Replacement Registry. World J Orthop 2025; 16(7): 106281

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v16/i7/106281.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v16.i7.106281

Degenerative knee disease affects around 23% of people over 40 years[1] and can have a negative impact on quality of life[2] due to pain, joint stiffness, and muscle weakness[3]. End-stage degenerative osteoarthritis (OA), due to primary or post-traumatic OA, is the documented indication for surgery in nearly 97% of primary knee procedures[4]. The projection of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) performed annually in the United States is expected to reach 1.26–1.92 million by 2030[5,6]. The majority of TKAs have been performed on patients 65 years of age or older, however, the rise in TKA performed in patients aged 44 to 64 years has decreased the average age at which patients receive a TKA[7]. These numbers suggest that there is, and will continue to be, a large number of patients that can benefit from knee replacement surgery and that there is a high demand from surgeons for knee prosthesis companies to offer safe and effective products for a diverse patient group.

There are two types of knee prostheses with regards to retention or resection of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) during surgery: Posterior-stabilized (PS) and cruciate-retaining (CR) designs. This study investigates both design types. The CR design traditionally preserves the PCL and preservation of the PCL can help in maintaining physiological knee kinematics and is normally indicated for patients with an intact or functional PCL, as it aims to replicate the natural knee function by allowing the ligament to guide knee movement[8]. The Truliant Cruciate Retaining Knee System is considered a semi-constrained type of knee prosthesis where the PCL is retained when using a CR insert. The PS design sacrifices the PCL and it is substituted with a cam and post implant design on the femur and polyethylene components, respectively. This replicates the function of the PCL, specifically limiting the femur from translating anteriorly on the tibia and causing femoral rollback as the knee is flexed. This design type is normally indicated for patients without an intact or functional PCL, or those who may be at an increased risk for the PCL failing in the future. The Truliant Posterior Stabilized Knee System is also considered a semi-constrained knee prosthesis. Several studies have found no significant differences in general function or survivorship of PS and CR implant types[9-13]. However, surgeons utilize different surgical techniques between the two design types. For example, with regard to the tibial slope, the CR posterior slope is important to maintain the appropriate tension and function of the PCL since excessive slope can cause PCL laxity and inadequate slope can cause PCL tightness[14]. Alternatively, for PS TKA, the tibial slope influences the cam-post mechanism, which is what mimics the PCL. The slope is typically reduced to obtain proper engagement and avoid excessive stress[14]. The choice between PS and CR designs should be based on factors such as patient characteristics, ligament integrity, surgeon experience, and desired postoperative outcomes.

To investigate the success of TKA implants, the rate at which the implants are revised, or replaced, is statistically assessed via survivorship. Survivorship refers to the long-term success and durability of the implants in patients who have undergone TKA. Traditionally, the survivorship of TKAs has been used to gain valuable information on implant safety and help identify potential issues or trends that may affect long-term patient outcomes.

Beginning in August 2021, Exactech Inc. initiated a voluntary recall of non-conforming packaging used for knee inserts and patellae including those used in the Truliant Knee Systems. The non-conformity involved polyethylene packaging without the specified ethylene vinyl alcohol (EVOH) layer. Exactech used two different types of packaging materials: Low Density Polyethylene (LDPE)/Nylon/EVOH, and LDPE/Nylon. Nylon alone provides a barrier that limits oxygen permeation, but EVOH is intended to add a secondary barrier to oxygen permeation. Potential issues due to oxidation may include accelerated device wear or failure, component cracking or fracture, new or worsening pain, bone loss, and/or swelling in the affected area, which could necessitate revision surgery.

The purpose of this study was to report short-term post-operative survivorship for the Truliant PS and CR Knee Systems utilizing the American Joint Replacement Registry (AJRR). The AJRR includes Truliant knee systems involved in the voluntary recall. Dissemination of these data will help surgeons plan surveillance of their Truliant patients and allow them to better evaluate the clinical urgency for doing so. Approximately eighty percent of knee inserts/patellae were in non-conforming packaging, so this dataset largely represents outcomes from subjects with implants with non-conforming (recalled) packaging. Unfortunately, however, it was not possible to separate conforming and non-conforming packaging in this report. Despite the non-conforming (recalled) packaging, it was hypothesized that Truliant PS and Truliant CR perform comparably to similar designs in measures of survivorship and reasons for revision.

This retrospective study included four groups of TKA subjects from the AJRR database. The four groups included all subjects implanted with (1) Truliant PS Total Knee System (Exactech Inc.); (2) All non-Truliant PS knee systems (termed aggregate PS); (3) Truliant CR Total Knee System (Exactech Inc.); and (4) All non-Truliant CR knee systems (termed aggregate CR). The data cutoff dates for all groups were January 2, 2012 to June 30, 2022, though registry data were not available for Truliant PS until 2017 and Truliant CR until 2018.

Representatives from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons included for analysis all cases with data deemed sufficient by AJRR (i.e., laterality, site, and patient ID were available and cases were not excluded for the reasons below). Linked revisions were defined as those cases with a primary knee arthroplasty and associated revision matching on patient ID, laterality, and site. Linked revisions and unlinked primary procedures were tracked for up to 10.5 years when applicable (i.e., in the aggregate groups). All AJRR component information for Medicare-eligible patients was merged to available Medicare claims data using a unique identifier provided by the Research Data Assistance Center. Subsequently, each procedure was categorized using International Classification of Diseases 9 and 10 procedure codes as a replacement or revision.

Exclusions were made for linked outcome cases if laterality could not be verified within AJRR or the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services database or if the primary procedure date came after the revision date. These exclusion criteria are critical to ensure the validity of the revision data whereby incorrect coding of a procedure as a revision would cause false positives in the data.

Continuous data were analyzed using t tests and categorical data (including reason for revision) were compared using χ2 tests. An age- and sex-adjusted hazard ratio was produced with 95% confidence interval and P value to determine statistical significance for survivorship. The statistical analysis was performed and reviewed by a biomedical statistician at the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

Cumulative percent revision rates for comparable PS and CR procedures were pulled from the 2022 annual reports of both the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry and the United Kingdom (UK) National Joint Registry (NJR). These cumulative percent revision rate confidence intervals were compared qualitatively to the Truliant and non-Truliant PS and CR rates from the AJRR.

Limitations of the study design include analysis that is not restricted to subjects above 65 years of age so there could be revisions performed that do not report to AJRR, which would not be reflected in this dataset.

This study was exempt from Institutional Review Board review and approval based on the exemption criteria included in 45 CFR 46.104.

According to the AJRR, a total of 1687 Truliant PS and 653 Truliant CR TKAs were performed prior to the data cutoff date of June 30, 2022. Those data were compared to 523234 aggregate PS and 537840 aggregate CR TKAs. The demographics and reasons for revisions are shown in Tables 1 and 2 for PS and CR groups, respectively. Demographic data for both groups are largely unremarkable and similar except that significantly fewer subjects in both the Truliant PS and Truliant CR groups had a primary OA diagnosis relative to the respective aggregate group.

| Characteristic | Truliant PS (n = 1687) | Aggregate PS (n = 523234) | P value |

| Average age, years (SD) | 67.2 (9.7) | 67.3 (9.4) | 0.56 |

| Average follow-up, months (SD) | 31.2 (16.5) | 56.5 (28.7) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.51 | ||

| Male | 650 (38.5) | 205110 (39.3) | |

| Female | 1037 (61.5) | 316630 (60.7) | |

| Missing | 0 | 1494 | |

| Charlson index, mean (SD) | 2.57 (1.41) | 2.71 (1.47) | < 0.001 |

| Fallout due to patient death | 1 (0.06) | 3921 (0.75) | 0.001 |

| Primary osteoarthritis diagnosis | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 1517 (93.3) | 497650 (97.3) | |

| No | 109 (6.7) | 13942 (2.7) | |

| Reason for revision | |||

| All cause | 26 (1.54) | 10499 (2.0) | 0.17 |

| Mechanical complications | 3 (0.18) | 803 (0.15) | 0.80 |

| Mechanical loosening | 4 (0.24) | 1743 (0.33) | 0.49 |

| Instability | 4 (0.24) | 1152 (0.22) | 0.88 |

| Infection | 9 (0.53) | 2964 (0.57) | 0.86 |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 0 (0) | 171 (0.03) | 0.46 |

| Other fractures | 0 (0) | 424 (0.08) | 0.24 |

| Fracture or related sequelae | 0 (0) | 448 (0.09) | 0.23 |

| Articular surface wear | 0 (0) | 38 (0.01) | 0.73 |

| Pain | 0 (0) | 1175 (0.22) | 0.05 |

| Hematoma or wound complication | 0 (0) | 302 (0.06) | 0.32 |

| All other diagnoses | 6 (0.36) | 2921 (0.56) | 0.26 |

| Characteristic | Truliant CR (n = 653) | Aggregate CR (n = 537840) | P value |

| Age, years (SD) | 68 (9.1) | 67.3 (9.3) | 0.045 |

| Average follow-up, months (SD) | 28.0 (13.4) | 52.4 (29.6) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.12 | ||

| Male | 240 (36.8) | 213312 (39.7) | |

| Female | 413 (63.3) | 323421 (60.3) | |

| Missing | 0 | 1107 | |

| Charlson index, mean (SD) | 2.74 (1.37) | 2.68 (1.42) | 0.32 |

| Fallout due to patient death | 1 (0.15) | 3419 (0.64) | 0.12 |

| Primary osteoarthritis diagnosis | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 561 (90.2) | 513415 (97.7) | |

| No | 61 (9.8) | 11846 (2.3) | |

| Reason for revision | |||

| All cause | 2 (0.31) | 6974 (1.3) | 0.025 |

| Mechanical complications | 0 (0) | 486 (0.09) | 0.44 |

| Mechanical loosening | 0 (0) | 878 (0.16) | 0.3 |

| Instability | 0 (0) | 855 (0.16) | 0.31 |

| Infection | 0 (0) | 2078 (0.39) | 0.11 |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 0 (0) | 60 (0.01) | 0.79 |

| Other fractures | 0 (0) | 217 (0.04) | 0.61 |

| Fracture or related sequelae | 0 (0) | 222 (0.04) | 0.6 |

| Articular surface wear | 0 (0) | 55 (0.01) | 0.8 |

| Pain | 0 (0) | 819 (0.15) | 0.32 |

| Hematoma or wound complication | 0 (0) | 179 (0.03) | 0.64 |

| All other diagnoses | 2 (0.31) | 2133 (0.4) | 0.71 |

All cause revision rates were similar for the Truliant PS group compared to the aggregate PS group (Table 1). All cause revision rates were significantly lower in the Truliant CR group compared to the aggregate CR group (Table 2), though this may be due to the significantly lower length of follow-up time for the Truliant CR group and the longer duration of data collection for the aggregate CR group (2012-2022). Truliant PS and aggregate PS groups show statistically similar rates in every individual reason for revision category (Table 1). Truliant CR and aggregate CR groups also show statistically similar rates in every individual reason for revision category (Table 2).

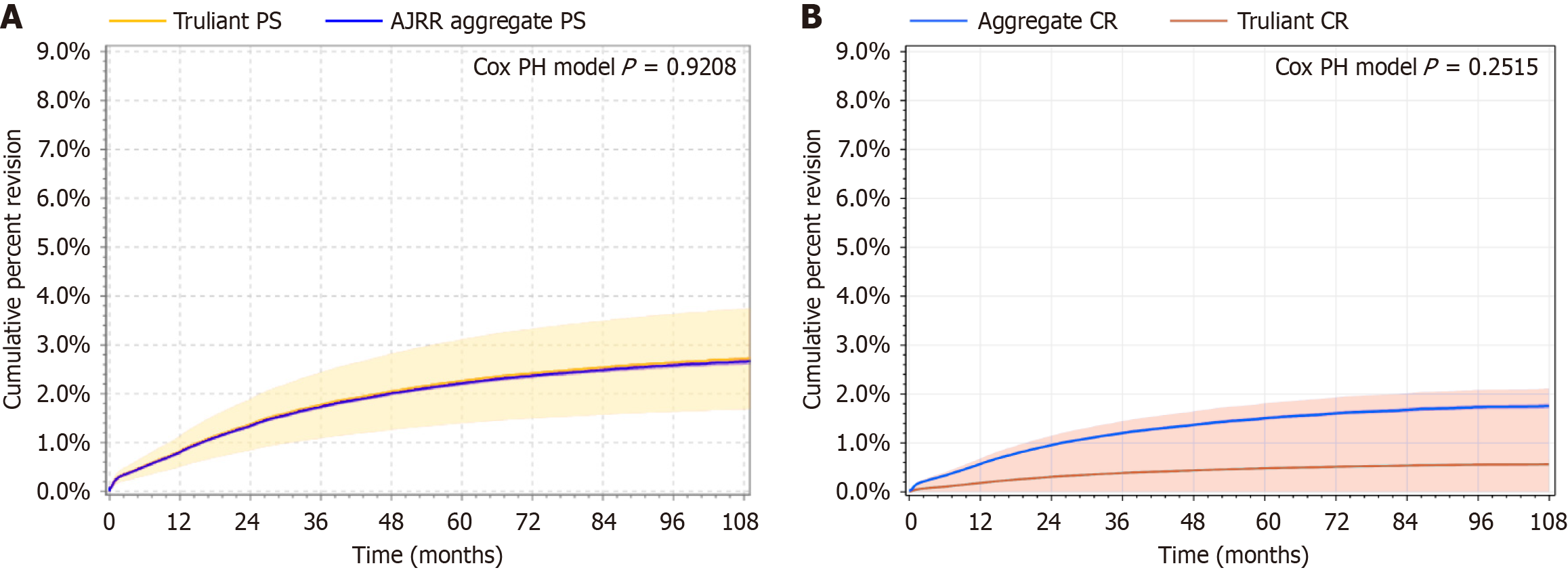

Cumulative percent revision rates for the Truliant PS and aggregate PS groups (Figure 1A) were comparable based on the calculated age- and sex-adjusted hazard ratio of 1.02 (95%CI: 0.685-1.52) with a P value of 0.92. Cumulative percent revision rates across time for both PS groups are included in Table 3. Cumulative percent revision rates for the Truliant CR and aggregate CR groups (Figure 1B) were comparable based on the age- and sex-adjusted hazard ratio of 0.32 (95%CI: 0.046-2.245) with a P value of 0.25. Cumulative percent revision rates across time for both CR groups are included in Table 4. Truliant PS survivorship was 97.95% at the 4-year mark, while Truliant CR survivorship was 99.61% at the 3-year mark. Data at later time points are also included in Tables 3 and 4 but cumulative percent revision rates are statistically unreliable when calculated with a sample size less than 40 at risk.

| Years to revision | Cumulative percent revision % (number at risk) | |

| Truliant PS (n = 1687) | Aggregate PS (n = 524921) | |

| 0 | 0.07 (1687) | 0.06 (521740) |

| 1 | 0.82 (1398) | 0.8 (484679) |

| 2 | 1.37 (1045) | 1.34 (435662) |

| 3 | 1.76 (718) | 1.73 (385269) |

| 4 | 2.05 (366) | 2.01 (320979) |

| 5 | 2.26 (121) | 2.22 (243128) |

| 6 | 2.42 (21) | 2.37 (162578) |

| 7 | 2.53 (21) | 2.48 (97209) |

| 8 | 2.64 (21) | 2.58 (49027) |

| 9 | 2.71 (01) | 2.65 (18461) |

| Years to revision | Cumulative percent revision % (number at risk) | |

| Truliant CR (n = 653) | Aggregate CR (n = 537840) | |

| 0 | 0.01 (653) | 0.02 (536733) |

| 1 | 0.18 (544) | 0.57 (486846) |

| 2 | 0.31 (398) | 0.95 (420494) |

| 3 | 0.39 (208) | 1.2 (360904) |

| 4 | 0.44 (351) | 1.37 (290143) |

| 5 | 0.48 (11) | 1.51 (216888) |

| 6 | 0.52 (11) | 1.60 (147845) |

| 7 | 0.54 (11) | 1.67 (89727) |

| 8 | 0.56 (11) | 1.73 (45593) |

| 9 | 0.56 (01) | 1.75 (17960) |

Additional comparisons were made against the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR) 2022 Annual Report[15], which provided stratifications for PS and minimally stabilized (analogous to the Truliant CR group) TKA (Table 5). The cumulative percent revision confidence intervals provided in the annual report suggest Truliant PS is comparable to the AOANJRR data at one-year and at least as low at three-years post-operative. Non-Truliant minimally stabilized TKA AOANJRR data also show that Truliant CR cumulative percent revision confidence intervals are at least as low as the AOANJRR data at both early time points.

| Registry | PS | CR/minimally stabilized/unconstrained | ||

| 1 year, rate (95%CI) | 3 years, rate (95%CI) | 1 year, rate (95%CI) | 3 years, rate (95%CI) | |

| AJRR (Truliant data) | 0.82 (0.51-1.13) | 1.76 (1.09- 2.43) | 0.18 (0-0.44) | 0.39 (0-0.92) |

| AJRR (non-Truliant data) | 0.8 (0.78-0.83) | 1.73 (1.69-1.77) | 0.57 (0.55-0.59) | 1.2 (1.17-1.23) |

| AOANJRR (all non-Truliant data)[13] | 1.2 (1.1-1.2) | 2.8 (2.7-2.9) | 0.9 (0.9-0.9) | 2.3 (2.3-2.4) |

| UK NJR (all non-Truliant data)[14] | 0.48 (0.45-0.5) | 1.65 (1.6-1.7) | 0.38 (0.37-0.40) | 1.33 (1.30-1.36) |

To further compare short-term results of the Truliant knee systems, comparisons were made to the UK NJR 2022 Annual Report[16], which also provides stratifications for PS and unconstrained (analogous to the Truliant CR group) TKA (Table 5). Non-Truliant PS UK NJR cumulative percent revision confidence intervals suggest Truliant PS is trending similar to the UK NJR data at the one-year mark and comparable at the three-year mark. Non-Truliant unconstrained TKA UK NJR cumulative percent revision rate confidence intervals also suggest Truliant CR is comparable to the UK NJR data at one year and at least as low at three years.

Cumulative percent revision rates for subjects receiving a Truliant PS or CR TKA remained low and comparable (according to the hazard ratios) to their respective aggregate groups in this analysis from the AJRR. When revision occurred, there were no significant differences in the reasons for revision between the Truliant and aggregate groups.

Furthermore, the registry data (AJRR, AOANJRR, and UK NJR) show non-overlapping confidence intervals for cumulative percent revision rates for both the non-Truliant PS and the non-Truliant unconstrained/minimally constrained groups at each early time point (Table 5). This strongly suggests meaningful differences in short-term outcomes across the three different registries for non-Truliant PS and CR-like knee systems. Given this variability it may be hard to detect an impact of Truliant’s non-conforming packaging on cumulative percent revision rates when comparing against aggregate groups. The most appropriate comparison for now is the Truliant vs non-Truliant aggregate analyses from the AJRR. Those are the comparisons that were analyzed statistically in this report, which show non-significant differences in both survivorship and reason for revision for both Truliant PS and Truliant CR designs.

Inter-registry heterogeneity should be considered when evaluating Truliant PS and CR designs against similar designs in the AOANJRR and UK NJR, given that Truliant PS and CR data were only available from AJRR. Completeness and coverage have been analyzed across national registries though data were not available from AJRR[17], which makes it difficult to assess the impact of those factors on inter-registry heterogeneity. But in terms of survivorship, a 2024 study[18] showed statistically similar values for a selected group of PS and CR designs across AJRR and UK NJR. This suggests that any differences in patient demographics, surgical practices, revision criteria, coverage, or completeness may not significantly affect survivorship rates across these two registries. Demonstrating generalizability across registries is a known challenge[19], which is why statistical comparisons were performed only on the AJRR data.

There are several limitations to registry studies. The AJRR is a voluntary registry, which creates a potential selection bias. There is also the potential for unmeasured confounders both within and across the datasets. Inherent in a registry study is the retrospective design and the potential underreporting or coding errors in the uploaded data. For this specific study there is also a limitation of short-term follow-up and a very low number of revisions in the Truliant CR group. These low frequencies limit the reliability of statistical comparisons though in the direction of lower P values. Most of the p values reported here were not statistically significant and the significant result (i.e., the number of revisions in the Truliant CR group) was deferred to the more appropriate hazard ratio calculation. Finally, a critical limitation is the lack of clinical functional outcomes. The number of sites reporting patient-reported outcome measures to AJRR has increased over time but was very low during the years assessed in this study (2012-2022)[20], and hence wasn’t included in this study.

It will be important to be fully transparent regarding Truliant PS and Truliant CR safety outcomes from products implanted before the 2021 voluntary recall to keep surgeons informed on the qualitative and quantitative effects on patient outcomes. There may be a lag time in onset of polyethylene wear, symptom onset, identification, and possible revision, so this topic warrants further research. Publication of this dataset helps surgeons to be aware of this implant’s early survivorship in a large national registry. Given the potential lag time between implantation and possible oxidation, medium and long-term outcomes from AJRR will be published as the data become available to better understand the possible impact of the non-conforming packaging.

Surgeons who implanted Truliant Total Knee Systems in the PS and CR design before the voluntary recall in August 2021 deserve to know the survivorship of those implants as the data become available. These analyses of short-term outcomes show no significant differences in cumulative percent revision rate in a registry sample of Truliant PS- and Truliant CR-implanted vs non-Truliant subjects where approximately eighty percent of the Truliant products were placed in non-conforming, and thus recalled, packaging. The clinical implications are that early survivorship of Truliant PS and CR designs is comparable to other PS and CR implants, respectively, but surgeons should closely monitor the affected knee patients for potential wear, osteolysis, and associated failure modes. If a failed device is suspected, consider performing X-rays to further evaluate the device. Pre-emptive removal of non-painful, well-functioning devices from asymptomatic patients is not recommended.

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and the American Joint Replacement Registry for providing the data and statistical analyses that made this publication possible.

| 1. | Cui A, Li H, Wang D, Zhong J, Chen Y, Lu H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29-30:100587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 719] [Article Influence: 143.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Alkan BM, Fidan F, Tosun A, Ardıçoğlu O. Quality of life and self-reported disability in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24:166-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sharma L. Osteoarthritis of the Knee. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:51-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 588] [Article Influence: 147.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Achakri H, Ben-Shlomo Y, Blom A, Boulton C, Bridgens J, Brittain R, Clark E, Dawson-Bowling S, Deere K, Esler C, Espinoza O, Evans J, Goldberg A, Gregson C, Hamoodi Z, Howard P, Jameson S, Jones T, Judge A, Lenguerrand E, Marques E, McCormack V, Newell C, Pegg D, Porter M, Price A, Reed M, Rees J, Royall M, Sayers A, Swanson M, Taylor D, Toms A, Watts A, Whitehouse M, Wilkinson M, Wilton T, Young E. The National Joint Registry 20th Annual Report 2023 [Internet]. London: National Joint Registry, 2022. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sloan M, Premkumar A, Sheth NP. Projected Volume of Primary Total Joint Arthroplasty in the U.S., 2014 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:1455-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 841] [Cited by in RCA: 1449] [Article Influence: 207.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Singh JA, Yu S, Chen L, Cleveland JD. Rates of Total Joint Replacement in the United States: Future Projections to 2020-2040 Using the National Inpatient Sample. J Rheumatol. 2019;46:1134-1140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 727] [Article Influence: 121.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Williams SN, Wolford ML, Bercovitz A. Hospitalization for Total Knee Replacement Among Inpatients Aged 45 and Over: United States, 2000-2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;1-8. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Ritter MA, Faris PM, Keating EM. Posterior cruciate ligament balancing during total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1988;3:323-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Worland RL, Jessup DE, Johnson J. Posterior cruciate recession in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:70-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bolanos AA, Colizza WA, McCann PD, Gotlin RS, Wootten ME, Kahn BA, Insall JN. A comparison of isokinetic strength testing and gait analysis in patients with posterior cruciate-retaining and substituting knee arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:906-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Conditt MA, Noble PC, Bertolusso R, Woody J, Parsley BS. The PCL significantly affects the functional outcome of total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:107-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Maruyama S, Yoshiya S, Matsui N, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M. Functional comparison of posterior cruciate-retaining versus posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:349-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Parsley BS, Conditt MA, Bertolusso R, Noble PC. Posterior cruciate ligament substitution is not essential for excellent postoperative outcomes in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:127-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | D'Anchise R, Andreata M, Balbino C, Manta N. Posterior cruciate ligament-retaining and posterior-stabilized total knee arthroplasty: differences in surgical technique. Joints. 2013;1:5-9. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR). Hip, knee & shoulder arthroplasty: 2022 annual report, Adelaide; AOA, 2022: 1-487. Available from: https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/annual-reports-2022. |

| 16. | Ben-Shlomo Y, Blom A, Boulton C, Brittain R, Clark E, Dawson-Bowling S, Deere K, Esler C, Espinoza O, Evans J, Goldberg A, Gregson C, Howard P, Jameson S, Jennison T, Judge A, Lawrence S, Lenguerrand E, Marques E, McCormack V, Newell C, Pegg D, Penfold C, Porter M, Price A, Reed M, Rees J, Royall M, Sayers A, Stonadge J, Swanson M, Taylor D, Toms A, Watts A, Whitehouse M, Wilkinson M, Wilton T, Young E. The National Joint Registry 19th annual report 2022 [Internet]. London: National Joint Registry; 2022. [PubMed] |

| 17. | French JMR, Deere K, Whitehouse MR, Pegg DJ, Ciminello E, Valentini R, Torre M, Mäkelä K, Lübbeke A, Bohm ER, Fenstad AM, Furnes O, Hallan G, Willis J, Overgaard S, Rolfson O, Sayers A. The completeness of national hip and knee replacement registers. Acta Orthop. 2024;95:654-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Springer BD, Mullen KP, Donnelly PC, Tucker K, Caton E, Huddleston JI. Is American Joint Replacement Registry Data Consistent With International Survivorship in Hip and Knee Arthroplasty? A Comparative Analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39:S46-S50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ingelsrud LH, Wilkinson JM, Overgaard S, Rolfson O, Hallstrom B, Navarro RA, Terner M, Karmakar-Hore S, Webster G, Slawomirski L, Sayers A, Kendir C, de Bienassis K, Klazinga N, Dahl AW, Bohm E. How do Patient-reported Outcome Scores in International Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Registries Compare? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2022;480:1884-1896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | American Joint Replacement Registry (AJRR). 2024 Annual Report. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), 2024. Available from: https://www.aaos.org/registries/publications/ajrr-annual-report/. |