Published online Aug 24, 2025. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v16.i8.108557

Revised: May 18, 2025

Accepted: July 24, 2025

Published online: August 24, 2025

Processing time: 125 Days and 16.3 Hours

Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the liver (MCN-L) are rare cystic lesions characterized by mucin-producing epithelium and ovarian-like stroma. Although they constitute fewer than 5% of hepatic cystic lesions, MCN-L poses significant diagnostic challenges due to overlapping features with other cystic lesions and their potential for malignant transformation. Early recognition and definitive surgical intervention are therefore critical to ensure optimal patient outcomes. A literature review was conducted to summarize epidemiology, clinical presen

Core Tip: Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the liver are rare cystic tumors with malignant potential, predominantly affecting middle-aged women. The 2010 World Health Organization classification distinguishes them from other hepatic cysts based on the presence of ovarian-like stroma. The differential diagnosis is challenging, as imaging features often overlap with other cystic liver lesions. Given the risk of recurrence and malignant transformation, complete surgical resection remains the treatment of choice. Histopathological confirmation is essential for definitive diagnosis.

- Citation: Cicerone O, Basilico G, Tassi C, Antoniacomi C, Lucev F, Corallo S, Vanoli A, Maestri M. Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the liver: Literature review and case series. World J Clin Oncol 2025; 16(8): 108557

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v16/i8/108557.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v16.i8.108557

Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the liver (MCN-L) are rare cystic lesions that represent less than 5% of all hepatic cysts[1]. However, in a surgical series, they account for approximately 10% of hepatic cysts[2].

Despite their rarity, they pose significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, particularly due to overlapping features with other hepatic cystic lesions and their potential for malignant transformation. The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) Guidelines provide comprehensive insights into the imaging features and surgical ma

MCN-L predominantly affects middle-aged women, typically between the ages of 40 and 70, although rare cases in teenagers have been documented[5]. The exact prevalence is challenging to ascertain because these lesions were historically classified under broader terms like “biliary cystadenomas” and “cystadenocarcinomas”. The 2010 WHO classification refined these definitions, emphasizing the presence of ovarian-like stroma as a diagnostic criterion[1,6].

MCN-L is now defined as “a cyst forming epithelial neoplasm, usually with no communication with the bile ducts, composed of cuboidal to columnar, variably mucin-producing epithelium, associated with ovarian-type subepithelial stroma” and is subdivided into non-invasive and invasive types[7]. This definition was maintained in the 2019 WHO classification of digestive system tumors[4].

Patients with MCN-L are often asymptomatic until the lesion reaches a significant size, typically over 10 cm, at which point they may present with nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain, fullness, or discomfort[1]. In rare cases, symptoms like jaundice or weight loss may occur due to the mass effect on adjacent structures. The indolent nature of these tumors contributes to delayed diagnosis and management[8]. In the case presented by Moriuchi et al[5], the teenage patient initially exhibited epigastric pain, and imaging revealed a 35-mm cystic mass in the liver, which grew to 75 mm over eight months. These findings highlight the variability in clinical presentation and the potential for rapid cyst growth, even in younger patients.

The differentiation of MCN-L from simple hepatic cysts (SHCs), particularly those complicated by hemorrhage or infection, is challenging. Imaging modalities such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) play crucial roles in the evaluation. MCN-L typically appears as multilocular cystic lesions with septations and may show internal nodules or calcifications[7]. However, distinguishing benign from malignant lesions based on imaging alone remains difficult.

The 2022 EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of cystic liver diseases mark a significant advancement in the standardized approach to diagnosing and treating MCN-L. The guidelines underscore the critical role of enhanced radiological imaging techniques in the accurate mapping and evaluation of cystic liver lesions. They recommend that ultrasound be the first imaging modality for the diagnosis of simple hepatic cysts, while MRI or CT should be utilized for cysts demonstrating complex features such as atypical cyst walls or contents, ensuring a comprehensive assessment of cyst architecture and its relation to hepatic vasculature[9].

These guidelines also introduced criteria to stratify the suspicion of MCN-L into high and low categories based on imaging features. High suspicion is defined by the presence of at least one major and one minor worrisome feature, while low suspicion involves the absence of such combinations[3]. Major features include nodularity, thick septations (> 3 mm), and internal hemorrhage, while minor features encompass upstream biliary dilatation, thin septations (< 3 mm), perilesional perfusion changes, and the presence of fewer than three co-existent hepatic cysts.

Despite these criteria, the EASL guidelines demonstrated a sensitivity of only 40% and a specificity of 80% in differentiating MCN-L from other cystic lesions in a retrospective cohort study[3]. This underscores the persistent challenge of accurate preoperative diagnosis.

Moreover, the guidelines highlight the limited utility of serum and cyst fluid markers like carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) in distinguishing MCN-L from other hepatic cysts, advocating instead for reliance on imaging characteristics and clinical presentation. Interestingly, tumor-associated glycoprotein 72 in cyst fluid has shown promise in differentiating between simple hepatic cysts and MCNs, though its application is currently constrained by limited data[9].

The EASL guidelines also stress the importance of surgical intervention in cases of MCN-L exhibiting worrisome features. Complete surgical resection is recommended for cysts with major features such as thick septations, nodularity, or internal hemorrhage, particularly when accompanied by minor features like upstream biliary dilatation or perilesional perfusion changes. This approach is grounded in evidence suggesting that incomplete resection or non-surgical in

The integration of these guidelines into clinical practice aims to enhance diagnostic accuracy and optimize patient outcomes by providing a structured framework for the evaluation and management of MCN-L.

The differential diagnosis of MCN-L encompasses a variety of hepatic cystic lesions, each with distinctive clinical and imaging features. One of the primary considerations is the intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct (IPNB), which often presents with cystic or tubular dilation of the bile ducts accompanied by visible papillary projections on imaging. Unlike MCN-L, IPNB typically communicates with the bile ducts, a characteristic that can be identified using magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). The presence of these papillary projections within the bile ducts, often associated with biliary dilatation, can be a significant indicator pointing toward IPNB rather than MCN-L[7,10].

Echinococcal cysts also enter the differential, particularly in endemic regions. These parasitic cysts often display calcifications and may contain daughter cysts within the primary cyst. Imaging findings, such as the "water lily sign" due to the detachment of the endocyst from the pericyst, can be highly suggestive. Moreover, serological tests for echinococcal antigens can assist in confirming the diagnosis[11,12].

SHCs, although the most benign of the entities considered, must also be differentiated from MCN-L. SHCs are typically unilocular with thin, smooth walls and lack internal septations or nodules. They exhibit water-like attenuation on CT and appear anechoic on ultrasound with posterior acoustic enhancement. The absence of enhancement post-contrast administration further distinguishes SHCs from neoplastic cysts like MCN-L, which may show wall thickening or nodularity[7].

A recent study by Boyum et al[13] provided additional insights into differentiating MCN-L from simple biliary cysts using imaging features. Their findings revealed that septations arising from the cyst wall without indentation were 100% sensitive for detecting hepatic MCN on CT, although the specificity was only 56.3%. Conversely, septations arising solely from external macrolobulations were 100% specific for simple biliary cysts, highlighting a key distinguishing feature between the two entities[13].

Moreover, septal enhancement on MRI was shown to have 100% sensitivity for hepatic MCN, further supporting its diagnostic value. However, this feature was also present in 47.1% of simple biliary cysts, limiting its specificity[13]. The study emphasized the importance of evaluating the relationship of septations to the cyst wall, with septations arising from the wall without indentation being a reliable indicator of MCN-L.

Gao et al[14] significantly contributed to the preoperative diagnosis of MCN-L by developing a predictive nomogram based on three independent factors: Contrast enhancement, tumor localization in the left lobe, and biliary duct dilatation. This tool demonstrated excellent discriminative ability with a C-index of 0.940, significantly improving the differentiation between MCN-L and simple hepatic cysts.

The proposed nomogram offers a practical approach for risk stratification, facilitating the identification of patients who may benefit from radical surgical resection vs those for whom less invasive treatment might suffice. This approach is particularly useful given the difficulty in differentiating MCN-L from simple cysts using conventional imaging, as demonstrated in the same study, where only 46.1% of MCN-L cases were correctly diagnosed via CT and 57.1% via MRI[14].

Despite these findings, differentiating MCN-L from simple hepatic cysts remains particularly challenging when the cystic lesion appears unilocular or shows very few septations. In such cases, an accurate diagnosis requires careful case-by-case assessment of the clinical context, imaging progression, and symptomatology. Occasionally, diagnostic un

Radiological imaging plays a pivotal role in the differentiation of MCN-L from other hepatic cystic lesions. Among the various imaging modalities, ultrasound, CT, and MRI offer complementary information that aids in the accurate diagnosis and characterization of MCN-L (Table 1).

| Criterion | Diagnostic importance |

| Multiloculated cystic lesion | Common feature of MCN-L |

| Septations | If > 3 mm, considered a major feature for high suspicion |

| Internal nodules | Major feature for high suspicion |

| Calcifications | Present in 47%-63% of cases |

| Thickened, irregular cyst walls | Common feature of MCN-L |

| Mural nodules with enhancement | Highly suggestive of MCN-L |

| Predilection for the left hepatic lobe (segment IV) | Found in 69%-76% of cases |

| Biliary duct dilatation | Minor feature |

| Absence of communication with bile ducts | Helps differentiate from IPNB |

| Echogenic septations (on ultrasound) | Key ultrasonographic feature |

| Contrast enhancement (on MRI) | Highly sensitive feature on MRI |

Ultrasound often serves as the first-line imaging technique due to its accessibility and non-invasive nature. On ultrasonography, MCN-L typically appears as a hypoechoic lesion with thickened, irregular walls and occasional internal echoes, which may represent debris or wall nodularity. These characteristics suggest a complex cyst, distinguishing it from simple hepatic cysts that usually appear as anechoic, thin-walled structures with smooth borders[7]. Furthermore, the presence of echogenic septa within the cyst is a hallmark feature of MCN-L, providing a clue toward its neoplastic nature[8].

CT offers superior delineation of the cyst’s dimensions, anatomic extent, and relationship to surrounding structures. MCN-L typically presents on CT as a large, well-circumscribed, multiloculated cystic mass with a clearly defined fibrotic capsule. Mural calcifications are observed in approximately 47%–63% of cases, providing a distinguishing feature from other cystic lesions. The presence of mural irregularity or nodules that enhance with intravenous contrast further supports the diagnosis of MCN-L. These nodules typically appear isodense to water, with Hounsfield units less than 30, and may be accompanied by intracystic debris, observed in 21%-40% of cases[8].

CT imaging also reveals a predilection of MCN-L for the left hepatic lobe, particularly segment IV, with 69%–76% of cases located in this region. This anatomical preference, combined with the presence of solitary cysts and biliary duct dilatation, enhances the diagnostic confidence for MCN-L. Importantly, biliary cystadenocarcinomas (BCAC) often exhibit more pronounced features on CT, such as calcifications, mural nodules, and wall enhancement, distinguishing them from their benign counterparts[8].

MRI is invaluable in further characterizing MCN-L due to its high contrast resolution and ability to differentiate tissue types. On MRI, MCN-L appears as multilocular cystic lesions with thick, irregular walls. Septal enhancement is a highly sensitive characteristic of MCN-L on MRI, surpassing CT in detecting capsular, septal, or nodular enhancement. T1-weighted images show varying cystic fluid signal intensities, influenced by the presence of proteinaceous or hemorrhagic contents. In contrast, T2-weighted images effectively identify intracystic septations and may reveal a low-signal-intensity rim indicative of calcifications or blood products[8].

MRCP further aids in the evaluation by providing detailed images of the biliary tree, helping to identify any communication between the cystic lesion and bile ducts - a feature typically absent in MCN-L. The lack of such co

Advanced imaging techniques, such as diffusion-weighted MRI (DW-MRI) and apparent diffusion coefficient mapping, have also shown promise in differentiating MCN-L from other cystic or necrotic liver tumors. DW-MRI can highlight differences in cellular density and the integrity of cell membranes, providing additional diagnostic information[7].

Despite these advanced imaging techniques, differentiating MCN-L from other cystic liver lesions remains challenging. The presence of multilocularity, thickened and irregular cyst walls, septations, and mural nodules are suggestive of MCN-L. However, definitive diagnosis often requires histopathological confirmation of ovarian-like stroma, under

Macroscopically, MCN-Ls are typically large (mean size: 11 cm) and multilocular cystic lesions surrounded by a fibrous capsule and with a mucinous or hemorrhagic content[16,17].

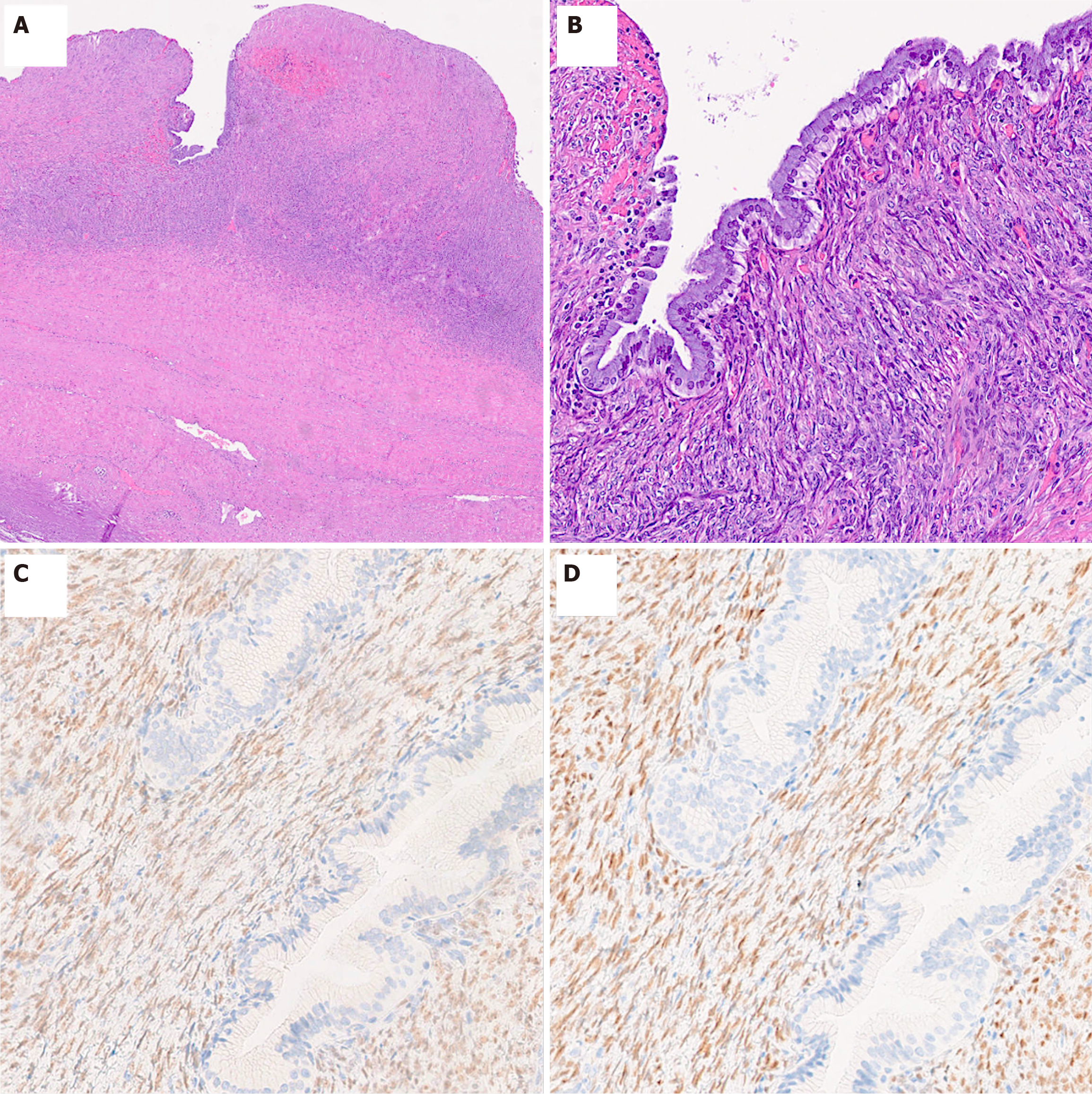

Histologically, MCN-L is characterized by cystic structures lined with dysplastic variably mucinous epithelium, and supported by ovarian-like subepithelial stroma, a hallmark feature that differentiates it from other hepatic cystic lesions[6,7]. The epithelium typically shows low-grade dysplasia and presents as a single layer of cuboidal to columnar cells and basally oriented nuclei. Some cases may display a mixture of mucinous and non-mucinous or biliary-type epithelium, suggesting a potential progression from biliary non-mucinous to mucinous epithelium[16]. Papillary epithelial projection within the cystic lumina, gastric and intestinal differentiation as well as squamous metaplasia may be seen. However, the transition to high-grade dysplasia/carcinoma in situ, which is characterized by marked architectural and cytologic atypia, with loss of nuclear polarity, as well as numerous mitotic figures, or invasive adenocarcinoma is relatively uncommon, with malignant transformation rates reported between 3% and 6% in certain case series[18]. Invasive carcinomas as

Immunohistochemically, the ovarian-like stroma exhibits strong positivity for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and Wilms tumor 1 protein. Additional markers include sex cord stromal markers such as steroidogenic factor 1, inhibin-α, and calretinin, which are significantly overexpressed compared to non-neoplastic liver tissue. This pattern of ex

Molecular analyses further reveal that MCN-L exhibits significant upregulation of genes involved in steroidogenesis, including 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 (HSD17B1), aromatase (CYP19A1), and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein. The expression of these enzymes underscores the stroma’s potential for sex hormone biosynthesis. Additionally, pathway analyses have identified the activation of oncogenic signaling pathways, particularly the hedgehog and Wnt pathways. The hedgehog pathway activation is corroborated by strong and diffuse immunohistochemical expression of GLI1 in both stromal and epithelial cells[18].

The downregulation of T-helper 1 and T-helper 2 immune pathways and interferon-gamma expression suggests an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, which may facilitate tumor progression and immune evasion. Despite extensive molecular investigations, common oncogenic mutations such as KRAS and RNF43 were rare or absent in MCN-L, differentiating it from its pancreatic counterparts. KRAS mutations have been reported to be very rare in cases with low-grade dysplasia (5%) but are frequently found with cases showing high-grade dysplasia[17]. Moreover, a recent investigation highlighted a gradual telomere shortening during the progression of MCN-L to adenocarcinoma[19]. Furthermore, heterozygous somatic mutations in SMO, a component of the hedgehog signaling pathway, were identified in a subset of cases, further implicating this pathway in MCN-L pathogenesis[18].

Although the etiology of MCN-L is currently unknown, these findings collectively support the hypothesis that MCN-L originates from ectopic primitive gonadal tissue or, alternatively, from liver stromal cells with the capacity to transdifferentiate into ovarian cortical cells. This unique histogenesis is reflected in the tumor’s distinctive morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular profiles, providing critical insights for accurate diagnosis and potential therapeutic targets (Table 2).

| Criterion | Diagnostic importance |

| Ovarian-like subepithelial stroma | Essential for MCN-L diagnosis and for differential diagnosis |

| Cuboidal to columnar cells, with variable mucin content | Typical histological appearance of the inner surface of the cysts |

| Basally oriented nuclei | Common nuclear arrangement |

| Immunohistochemical positivity of ovarian-like stroma for ER, PR, WT1 | Helps differentiate from other hepatic cystic lesions |

| Expression of SF-1, Inhibin-α, Calretinin in ovarian-like stroma | Suggests hormonal influence |

| Activation of Hedgehog and Wnt pathways | Associated with oncogenesis |

| Rarity or absence of KRAS and RNF43 mutations | Differentiates from pancreatic MCN |

| Shortening of telomers | Indicates progression to carcinoma |

The role of preoperative biopsy in the diagnostic workup of MCN-L remains limited and is generally discouraged due to several critical factors that outweigh its potential benefits. The foremost concern is the risk of tumor seeding. Puncturing a cystic neoplasm, especially one with malignant potential, can lead to the dissemination of tumor cells along the needle tract or into the peritoneal cavity. This seeding not only complicates the clinical course but also worsens the patient's prognosis by potentially facilitating the spread of malignancy[20].

Another significant limitation of preoperative biopsy is the frequent occurrence of inconclusive or non-representative results. The multilocular nature of MCN-L and the thick cyst walls pose challenges in obtaining adequate tissue samples. Fine-needle aspiration or core needle biopsy often fails to capture the ovarian-like stroma, which is essential for a definitive diagnosis. This stroma, characterized by its positivity for estrogen and progesterone receptors, is critical for distinguishing MCN-L from other hepatic cystic lesions. Without capturing this tissue, there is a high likelihood of false-negative results or misdiagnosis[1,7].

Furthermore, the histological hallmark of MCN-L—the presence of ovarian-like stroma—requires comprehensive tissue examination, which is best achieved through complete surgical resection[18].

Biochemical and cytological analyses of cyst fluid, while sometimes utilized, are also unreliable. Elevated levels of tumor markers such as CA19-9 and CEA in cyst fluid can occur in both benign and malignant cystic lesions, reducing their specificity and diagnostic utility. Additionally, cyst fluid cytology often fails to detect malignant cells due to the low cellularity of the fluid and the patchy distribution of neoplastic cells within the cyst lining[20]. Moreover, these markers may also be elevated in the fluid of simple hepatic cysts, further limiting their usefulness in differentiating mucinous neoplasms from non-neoplastic cystic lesions[21].

Hai et al[22] emphasized the difficulty in distinguishing cystadenoma from cystadenocarcinoma based solely on imaging or cytological evaluation. Their study demonstrated that cytology often fails to detect malignant cells in cystic hepatic lesions, and elevated serum markers like CEA and CA19-9 are not reliable indicators of malignancy, as they may also be elevated in benign cystadenomas. Consequently, they recommend considering hepatic resection when cystadenocarcinoma is suspected, as definitive diagnostic criteria remain elusive preoperatively.

Simo et al[23] further emphasized the diagnostic complexities, noting that clinical symptoms, serologic markers, and imaging modalities are often unreliable, leading to misdiagnosis in 55%–100% of patients. They highlighted that invasive biliary mucinous cystic neoplasms can only be reliably differentiated from non-invasive forms through microscopic evaluation for ovarian-type stroma, reinforcing the necessity of intraoperative biopsy and frozen section analysis for accurate diagnosis.

Arnaoutakis et al[24] highlighted that fine-needle biopsy (FNB) has significant limitations in diagnosing biliary cystic tumors, including MCN-L. In their study, FNB showed a sensitivity of only 50% for detecting BCAC, with several cases being misdiagnosed as benign or non-diagnostic. The specificity was high at 97.6%, but the risk of false negatives remains substantial, emphasizing the unreliability of biopsy in providing definitive preoperative diagnoses.

Given these limitations, current guidelines advocate for complete surgical resection not only as a therapeutic intervention but also as the definitive method for accurate diagnosis. Imaging modalities, including ultrasound, CT and MRI, provide sufficient preoperative information to guide surgical planning without the need for invasive biopsy procedures.

Complete surgical resection remains the cornerstone of MCN-L management due to the potential for malignant transformation and recurrence if inadequately treated[5,8,25]. Non-surgical treatments like aspiration, sclerotherapy, or cyst deroofing are discouraged due to high recurrence rates and risks of tumor seeding[20]. The choice of surgical technique, whether open, laparoscopic, or robotic, depends on the tumor's size, location, and the patient's overall health status[26].

The prognosis of MCN-L is generally favorable following complete resection, with recurrence being rare. The five-year survival rate is excellent, particularly in cases without invasive carcinoma[5]. However, cases with malignant transformation may have a poorer prognosis, underscoring the importance of early and accurate diagnosis and treatment[20].

The patient in Moriuchi et al[5] case demonstrated a favorable outcome post-surgery, with no signs of recurrence and an excellent quality of life at six months follow-up. This case underscores the importance of considering surgical intervention in symptomatic or rapidly growing MCN-L, even in younger patients.

Between January 2019 and March 2025, we evaluated 30 surgical procedures performed for hepatic cysts at our center. A total of 25 patients underwent surgery, some on multiple occasions. Among these, 9 cases were ultimately diagnosed as low-grade MCN-L based on histopathological examination.

Table 3 summarizes the characteristics of all patients, with each surgical procedure being considered as a separate entry in cases of multiple operations. The characteristics of the nine patients diagnosed with MCN-L are detailed in Table 4, including demographic data, clinical presentation, imaging findings, surgical approach and reintervention.

| Variable | N |

| Procedures | 30 |

| Patients | 25 |

| Sex (Male/Female) | 13/17 |

| Age (mean ± avg) | 58.867 ± 15.126 |

| BMI (mean ± avg) | 24.568 ± 4.137 |

| Symptoms (yes/no) | 24/6 |

| Imaging | |

| CT | n = 12 |

| MRI | n = 7 |

| US only | n = 11 |

| Size (cm) | 10.607 ± 4.609 |

| Growing volume (yes/no) | 21/6 |

| Septations (yes/no) | 10/17 |

| Calcifications (yes/no) | 3/24 |

| Mural nodules (yes/no) | 4/23 |

| Contrast enhancement (yes/no) | 3/24 |

| MCN-L on histological examination (yes/no) | 11/19 |

| Surgery | |

| Fenestration with pericystectomy | n = 24 |

| Resection | n = 6 |

| Surgical approach (VLS/OPEN) | 24/6 |

| Operative time (min) | 197.6 ± 105.565 |

| Length of stay (days) | 6.4 ± 4.304 |

| N of Reinterventions | 5 |

| Variable | N |

| Patients | 9 |

| Sex (Male/Female) | 1/8 |

| Age (mean ± avg) | 55.444 ± 16.622 |

| BMI (mean ± avg) | 22.989 ± 3.043 |

| Symptoms (yes/no) | 8/1 |

| Size (cm) | 8.078 ± 3.282 |

| Growing volume (yes/no) | 7/2 |

| Septations (yes/no) | 5/4 |

| Calcifications (yes/no) | 1/8 |

| Mural nodules (yes/no) | 2/7 |

| Contrast enhancement (yes/no) | 2/7 |

| Original surgery | |

| Fenestration with pericystectomy | n = 7 |

| Resection | n = 2 |

| Reinterventions | 2 |

| Surgery of the reinterventions | Resection |

Among the 25 patients who underwent hepatic cyst surgery, 17 were female and 13 were male, with a mean age of 58 years ± 15. Symptoms were present in 24 patients, while 6 were asymptomatic.

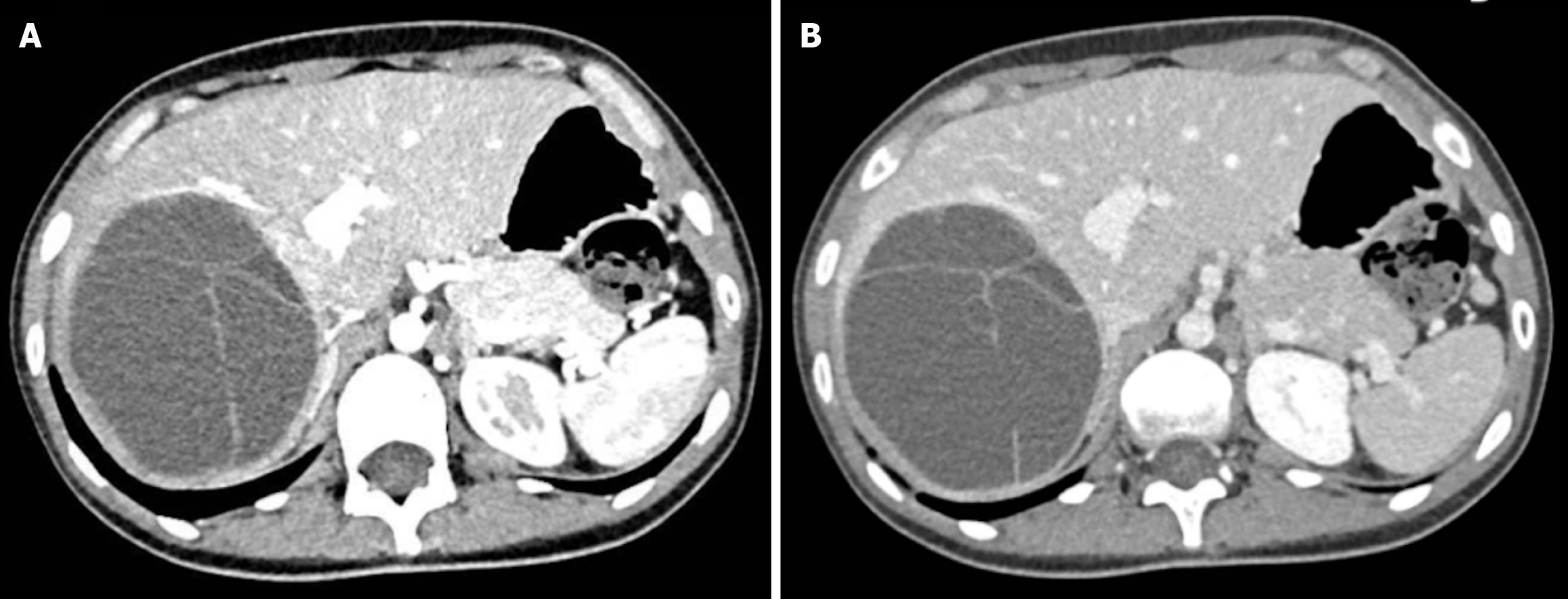

Among the 9 confirmed MCN-L cases, the majority were female (8 out of 9), reinforcing the established epidemiological trend of MCN-L predominantly affecting women. The mean age in this subset was 55 years ± 16, comparable to the overall cohort. Almost all MCN-L patients were symptomatic, primarily presenting with abdominal pain, upper quadrant discomfort, or pressure-related symptoms due to cyst enlargement. Growth over time was observed in 7 out of 9 MCN-L cases, raising clinical suspicion and warranting surgical intervention. Preoperative imaging features suggestive of MCN-L, such as internal septations, mural nodularity, and contrast enhancement, were not consistently present in all histologically confirmed MCN-L case. Among the 9 patients with a final histological diagnosis of MCN-L, preoperative imaging revealed septations in 5 cases, mural nodules in 2, contrast enhancement in 2, and calcifications in 1. However, some of these features—particularly septations—were also observed in patients who were ultimately not diagnosed with MCN-L. This overlap highlights the difficulty in reliably distinguishing MCN-L from other hepatic cystic lesions based solely on radiological features (Figure 1).

Of the 30 surgical procedures performed, 24 involved fenestrations with pericystectomy, while 6 consisted of hepatic resections. The surgical approach was laparoscopic in 24 cases and open in 6 cases. Among the six hepatic resections, four were performed in patients with a final histological diagnosis of MCN-L. In two of these cases, preoperative imaging findings raised a high suspicion for MCN-L, and patients were therefore directly treated with primary hepatic resection. In the remaining two cases, the lesions were initially considered not neoplastic and were managed with fenestration and pericystectomy. However, following histological diagnosis of MCN-L, both patients underwent a second surgery to achieve complete resection (Figure 2). For instance, fenestration with pericystectomy involved accessing the cyst through a laparoscopic or open approach, aspirating its fluid contents, and partial excision of the reactive cyst wall in contact with the hepatic parenchyma. This procedure was performed only in cases where the lesion was considered a simple hepatic cyst based on preoperative imaging.

Notably, one patient with simple hepatic cysts (and not MCN-L) required a second surgical intervention after experiencing traumatic cyst rupture due to accidental trauma, following an initial elective surgery for the treatment of the cysts. Conversely, one patient presented with pain and rapid cyst growth, which—although not specific for MCN-L—raised clinical suspicion of a mucinous cystic neoplasm based on the overall radiological and clinical context. However, final histological analysis confirmed a simple hepatic cyst.

Overall, the postoperative course was regular, with no perioperative mortality.

This case series reinforces the well-established epidemiological profile of MCN-L as a predominantly female-associated neoplasm with variable clinical presentation[16]. Imaging remains an essential tool in the preoperative workup, but as observed in our series, it is not always sufficient to achieve a definitive diagnosis[2]. The presence of septations, mural nodules, and contrast enhancement is helpful but not pathognomonic, necessitating histopathological confirmation for an accurate diagnosis. The surgical approach to MCN-L remains a critical factor in patient outcomes. Given the risk of recurrence and potential malignant transformation, hepatic resection should be considered in cases with strong suspicion of MCN-L, in order to achieve complete macroscopic removal of the lesion and minimize the risk of recurrence. Surgical planning should be guided by preoperative imaging and clinical assessment to select the most appropriate approach.

Further studies and larger multicentric analyses are needed to refine preoperative diagnostic criteria and optimize surgical strategies for these rare but clinically significant neoplasms.

| 1. | Hutchens JA, Lopez KJ, Ceppa EP. Mucinous Cystic Neoplasms of the Liver: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Hepat Med. 2023;15:33-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Armutlu A, Quigley B, Choi H, Basturk O, Akkas G, Pehlivanoglu B, Memis B, Jang KT, Erkan M, Erkan B, Balci S, Saka B, Bagci P, Farris AB, Kooby DA, Martin D, Kalb B, Maithel SK, Sarmiento J, Reid MD, Adsay NV. Hepatic Cysts: Reappraisal of the Classification, Terminology, Differential Diagnosis, and Clinicopathologic Characteristics in 258 Cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2022;46:1219-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Furumaya A, Schulz HH, Verheij J, Takkenberg RB, Besselink MG, Kazemier G, Erdmann JI, van Delden OM. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with suspected mucinous cystic neoplasms of the liver: a retrospective cohort study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2024;409:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F, Cree IA; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2554] [Cited by in RCA: 2436] [Article Influence: 487.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Moriuchi T, Hashimoto M, Kuroda S, Kobayashi T, Ohdan H. Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm of the Liver in a Teenager: A Case Report. Cureus. 2024;16:e65728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. WHO Classification of Tumours, 4th Edition, Volume 3. Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, editers. Available from: https://publications.iarc.who.int/Book-And-Report-Series/Who-Classification-Of-Tumours/WHO-Classification-Of-Tumours-Of-The-Digestive-System-2010. |

| 7. | Soni S, Pareek P, Narayan S, Varshney V. Mucinous cystic neoplasm of the liver (MCN-L): a rare presentation and review of the literature. Med Pharm Rep. 2021;94:366-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Aziz H, Hamad A, Afyouni S, Kamel IR, Pawlik TM. Management of Mucinous Cystic Neoplasms of the Liver. J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;27:1963-1970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of cystic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2022;77:1083-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Xiao SY, Shi YT, Xu JX, Sun JH, Yu RS. To develop a classification system which helps differentiate cystic intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct from mucinous cystic neoplasm of the liver. Eur J Radiol. 2025;182:111822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tholomier C, Wang Y, Aleynikova O, Vanounou T, Pelletier JS. Biliary mucinous cystic neoplasm mimicking a hydatid cyst: a case report and literature review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Muralidhar V, Santhaseelan RG, Ahmed M, Shanmuga P. Simultaneous occurrence of hepatic hydatid cyst and mucinous cystadenoma of the liver in a middle-aged female patient: report of a rare case. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Boyum JH, Sheedy SP, Graham RP, Olson JT, Babcock AT, Bolan CW, Menias CO, Venkatesh SK. Hepatic Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm Versus Simple Biliary Cyst: Assessment of Distinguishing Imaging Features Using CT and MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:403-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gao J, Zheng J, Cai J, Kirih MA, Xu J, Tao L, Liang Y, Feng X, Fang J, Liang X. Differentiation and management of hepatobiliary mucinous cystic neoplasms: a single centre experience for 8 years. BMC Surg. 2021;21:146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lachance E, Mandziuk J, Sergi CM, Bateman J, Low G. Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation of Liver Tumors. In: Liver Cancer [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications; 2021-Apr-6. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Quigley B, Reid MD, Pehlivanoglu B, Squires MH 3rd, Maithel S, Xue Y, Hyejeong C, Akkas G, Muraki T, Kooby DA, Sarmiento JM, Cardona K, Sekhar A, Krasinskas A, Adsay V. Hepatobiliary Mucinous Cystic Neoplasms With Ovarian Type Stroma (So-Called "Hepatobiliary Cystadenoma/Cystadenocarcinoma"): Clinicopathologic Analysis of 36 Cases Illustrates Rarity of Carcinomatous Change. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:95-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fujikura K, Akita M, Abe-Suzuki S, Itoh T, Zen Y. Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the liver and pancreas: relationship between KRAS driver mutations and disease progression. Histopathology. 2017;71:591-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Van Treeck BJ, Lotfalla M, Czeczok TW, Mounajjed T, Moreira RK, Allende DS, Reid MD, Naini BV, Westerhoff M, Adsay NV, Kerr SE, I Ilyas S, Smoot RL, Liu Y, Davila J, Graham RP. Molecular and Immunohistochemical Analysis of Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm of the Liver. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;154:837-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sung YN, Stojanova M, Shin S, Cho H, Heaphy CM, Hong SM. Gradual telomere shortening in the tumorigenesis of pancreatic and hepatic mucinous cystic neoplasms. Hum Pathol. 2024;152:105653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shi B, Yu P, Meng L, Li H, Wang Z, Cao L, Yan J, Shao Y, Zhang Y, Zhu Z. A paradigm shift in diagnosis and treatment innovation for mucinous cystic neoplasms of the liver. Sci Rep. 2024;14:16507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Choi HK, Lee JK, Lee KH, Lee KT, Rhee JC, Kim KH, Jang KT, Kim SH, Park Y. Differential diagnosis for intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and hepatic simple cyst: significance of cystic fluid analysis and radiologic findings. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:289-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hai S, Hirohashi K, Uenishi T, Yamamoto T, Shuto T, Tanaka H, Kubo S, Tanaka S, Kinoshita H. Surgical management of cystic hepatic neoplasms. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:759-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Simo KA, Mckillop IH, Ahrens WA, Martinie JB, Iannitti DA, Sindram D. Invasive biliary mucinous cystic neoplasm: a review. HPB (Oxford). 2012;14:725-740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Arnaoutakis DJ, Kim Y, Pulitano C, Zaydfudim V, Squires MH, Kooby D, Groeschl R, Alexandrescu S, Bauer TW, Bloomston M, Soares K, Marques H, Gamblin TC, Popescu I, Adams R, Nagorney D, Barroso E, Maithel SK, Crawford M, Sandroussi C, Marsh W, Pawlik TM. Management of biliary cystic tumors: a multi-institutional analysis of a rare liver tumor. Ann Surg. 2015;261:361-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Smerieri N, Fiorentini G, Ratti F, Cipriani F, Belli A, Aldrighetti L. Laparoscopic left hepatectomy for mucinous cystic neoplasm of the liver. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:1068-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Abu Hilal M, Di Fabio F, Teng MJ, Godfrey DA, Primrose JN, Pearce NW. Surgical management of benign and indeterminate hepatic lesions in the era of laparoscopic liver surgery. Dig Surg. 2011;28:232-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |