Published online Nov 6, 2015. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v6.i4.238

Peer-review started: May 28, 2015

First decision: June 18, 2015

Revised: July 15, 2015

Accepted: September 7, 2015

Article in press: September 8, 2015

Published online: November 6, 2015

Processing time: 170 Days and 14.8 Hours

AIM: To analyze whether the presence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection could affect the quality of symptoms in gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) patients.

METHODS: one hundred and forty-four consecutive patients referred to our Unit for suspected GERD were recruited for the study. All patients underwent esophageal pH-metric recording. For those with a positive test, C13 urea breath test was then performed to assess the H. pylori status. GERD patients were stratified according to the quality of their symptoms and classified as typical, if affected by heartburn and regurgitation, and atypical if complaining of chest pain, respiratory and ears, nose, and throat features. H. pylori-negative patients were also asked whether they had a previous diagnosis of H. pylori infection. If a positive response was given, on the basis of the time period after successful eradication, patients were considered as “eradicated” (E) if H. pylori eradication occurred more than six months earlier or “recently eradicated” if the therapy had been administered within the last six months. Patients without history of infection were identified as “negative” (N). χ2 test was performed by combining the clinical aspects with the H. pylori status.

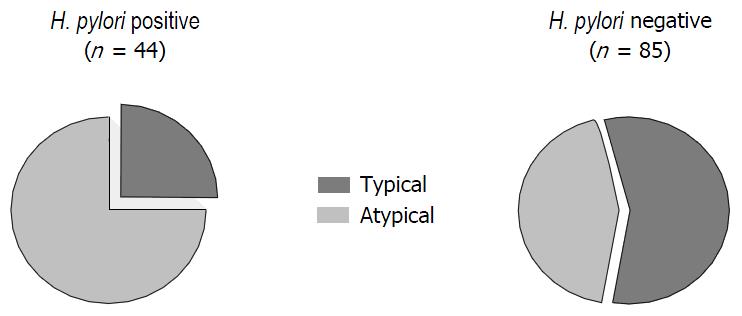

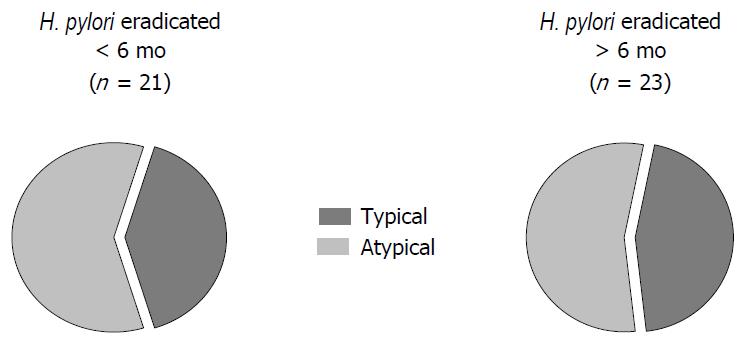

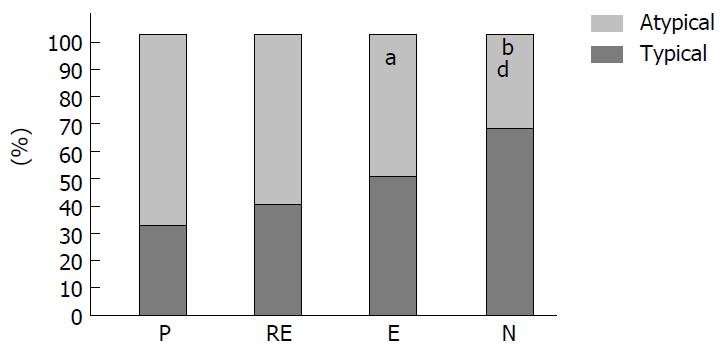

RESULTS: one hundred and twenty-nine of the 144 patients, including 44 H. pylori-positive and 85 H. pylori-negative (41 negative, 21 recently eradicated, 23 eradicated more than 6 mo before), were eligible for the analysis. No difference has been found between H. pylori status and either the number of reflux episodes (138 ± 23 vs 146 ± 36, respectively, P = 0.2, not significant) or the percentage of time with pH values < 4 (6.8 ± 1.2 vs 7.4 ± 2.1, respectively, P = 0.3, not significant). The distribution of symptoms was as follows: 13 typical (30%) and 31 atypical (70%) among the 44 H. pylori-positive cases; 44 typical (52%) and 41 atypical (48%) among the 85 H. pylori-negative cases, (P = 0.017 vs H. pylori+; OR = 2.55, 95%CI: 1.17-5.55). Furthermore, clinical signs in patients with recent H. pylori eradication were similar to those of H. pylori-positive (P = 0.49; OR = 1.46, 95%CI: 0.49-4.37); on the other hand, patients with ancient H. pylori eradication showed a clinical behavior similar to that of H. pylori-negative subjects (P = 0.13; OR = 0.89, 95%CI: 0.77-6.51) but different as compared to the H. pylori-positive group (P < 0.05; OR = 3.71, 95%CI: 0.83-16.47).

CONCLUSION: Atypical symptoms of GERD occur more frequently in H. pylori-positive patients than in H. pylori-negative subjects. In addition, atypical symptoms tend to decrease after H. pylori eradication.

Core tip: This study aimed to investigate whether the presence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection could affect the symptom pattern of patients with gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD). GERD patients with H. pylori were predominantly affected by atypical symptoms (chest pain, respiratory and ears, nose, and throat features) whilst patients without infection mainly referred typical GERD symptoms (heartburn, regurgitation). Therefore, it seems reasonable to assume that H. pylori infection may have a role in GERD pathogenesis or at least in the modulation of symptoms appearance.

-

Citation: Grossi L, Ciccaglione AF, Marzio L. Typical and atypical symptoms of gastro esophageal reflux disease: Does

Helicobacter pylori infection matter? World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2015; 6(4): 238-243 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v6/i4/238.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v6.i4.238

Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection represent two of the most common diseases affecting upper GI tract. GERD is clinically characterized by different patterns, generally identified as typical or atypical. Typical symptoms are heartburn and acid regurgitation[1], while atypical extraesophageal manifestations can include symptoms primarily attributable to other organs, such as chronic cough, non cardiac chest pain, chronic pharyngitis and laryngitis[2]. A small amount of patients refer symptoms (epigastric pain, nausea, belching, vomiting) that may overlap with other gastrointestinal conditions, such as dyspepsia, severe gastritis, peptic ulcer disease or hiatal hernia. Despite a huge amount of evidence on diagnosis and therapy of such different patients, limited information is available to explain why one can experience typical or atypical symptoms and whether the presence of H. pylori infection could affect the quality of symptoms in GERD patients. Whilst the role of H. pylori has been widely recognized in the pathogenesis of gastritis[3,4], peptic ulcer[5,6] and even gastric malignancies[7,8], there is conflicting evidence in the literature about a possible link between infection and natural history of GERD. Many authors proposed a “protective” role of H. pylori against acid refluxes, probably due to the reduced acid production in infected patients, but the exact mechanism is not well known[9]. On the contrary, other studies have demonstrated the lack of any influences between the two diseases[10]. Therefore, the question has been mainly limited to demonstrate whether H. pylori could protect from or facilitate the onset of pathological gastro-esophageal refluxes. In the present study we investigated whether H. pylori infection has a role in the clinical appearance of GERD.

We enrolled 144 consecutive patients undergoing esophageal 24-h pH-metric recording for suspected GERD on the basis of typical or atypical extraesophageal symptoms. To rule out overlapping with other upper GI diseases, we did not consider patients with epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting as predominant symptoms and scheduled for pH monitoring. The procedure was performed using a probe with a single glass electrode on the tip (Jubileum, Microbioprobe and Telemedicine srl, Marigliano-NA, Italy) connected to a portable data logger (pH-day, Menfis Biomedical, Bologna Italy). The main inclusion criteria was the confirmation of GERD by the pH monitoring, according to De Meester criteria[11]. All patients had a previous upper GI endoscopy within the last six months in order to exclude the presence of malignancies, Los Angeles grade C or D esophagitis, peptic ulcer, erosive gastritis, and hiatal hernia. In addition, recent full examinations by cardiologist, pneumologist and otolaryngologist were required to rule out specific diseases of their competence. All patients were required to complete a minimum four-week wash-out period of antisecretory drugs (PPI, H2-blockers) and medications potentially affecting upper GI motility (nitrates, calcium channel blockers, xanthines, benzodiazepines, and beta agonists), before entry into the study. Body mass index (BMI) was also calculated for all patients. Obese subjects (BMI > 30 kg/m2) were considered not eligible for the study and were excluded. Smoking habits were also recorded for all eligible patients.

Patients were divided in two groups according to their GERD symptoms: “Typical” including patients with symptoms such as heartburn and regurgitation, and “Atypical” including subjects with symptoms including chest pain, chronic cough and chronic pharingytis/laryngitis. If both kinds of symptoms were present, patients were asked to indicate the predominant one in terms of its impact on their daily activities. The subjects were then assigned accordingly to group A or group B.

A C13 Urea Breath Test was performed on all patients on the same day of pH-metric recording. Patients were classified as H. pylori-positive (H. pylori+) or H. pylori-negative (H. pylori-). H. pylori-negative patients were also asked whether they had a previous diagnosis of H. pylori infection. If a positive response was given, on the basis of the time period after successful eradication, patients were considered as “eradicated” (E) if H. pylori eradication occurred more than 6 mo earlier or “recently eradicated” (RE) if the therapy had been administered within the last six months. Patients without history of infection were identified as “negative” (N).

After collecting the data, χ2 test was performed to identify significant correlations between clinical aspects (i.e., typical or atypical) and H. pylori status (i.e., positive or negative; if negative: eradicated or recently eradicated). A P-value less than 0.05 (P < 0.05) was inferred significant. Odd ratio (OR) and 95%CI were also calculated. The primary endpoint was to find a correlation between symptoms pattern and H. pylori presence; then, we wanted to evaluate whether this correlation could change in relation of period of time after bacterial eradication.

Of the 144 initially enrolled subjects, 129 patients (73 male, 56 female, age: 19-65) resulted affected by GERD at 24-h pH monitoring. In this case series, 44 were H. pylori-positive and 85 were H. pylori-negative. No difference has been found between H. pylori status and either the number of reflux episodes (138 ± 23 vs 146 ± 36, respectively, P = 0.2, not significant) or the percentage of time with pH values < 4 (6.8 ± 1.2 vs 7.4 ± 2.1, respectively, P = 0.3, not significant). Among the negative group, 41 patients had no history of previous H. pylori infection (N), 21 patients had been recently H. pylori-eradicated (RE) and 23 patients had been successfully treated for H. pylori eradication more than six months earlier (E).

Typical symptoms of GERD were present in 57 patients (34 male, 23 female), whereas 72 patients (38 male, 34 female) resulted affected by atypical manifestations.

Among 129 patients with GERD, 12 subjects (7/72 patients of atypical group and 5/57 patients of typical group) had a BMI indicative of slight overweight, i.e., between 25 and 30 (9.7% vs 8.3%, respectively, P = 0.1, not significant). Furthermore, there were 41 active smokers with 22 patients among atypical group and 19 patients among typical group (30.5% vs 33.3%, respectively, P = 0.2, not significant).

Group H. pylori+: 31 of the 44 patients (70%) with H. pylori infection were affected by atypical symptoms, whereas 13 of them (30%) referred typical clinical signs. Group H. pylori-: 41 of the 85 patients (48%) without infection had atypical manifestations and 44 of them (52%) showed typical pattern (Figure 1). Group N: 16 of the 41 patients (35%) without H. pylori infection were affected by atypical symptoms, whereas 27 of them (65%) referred typical clinical signs. Group RE: 13 of 21 patients (62%) with recent H. pylori eradication had atypical symptoms and 8 of 21 (38%) presenting typical GERD manifestations (Figure 2). Group E: 12 of the 23 patients (52%) with H. pylori eradication performed more than 6 mo earlier had atypical GERD symptoms. Typical signs occurring in 9 patients (48%) (Figure 2).

Atypical GERD symptoms were significantly more frequent in H. pylori-positive than in H. pylori-negative patients (P = 0.017; OR = 2.55, 95%CI: 1.17-5.55). Also, patients with recent eradication of H. pylori infection had a predominance of atypical signs that resulted not significantly different from H. pylori-positive (P = 0.49; OR = 1.46, 95%CI: 0.49-4.37), but were different in comparison with H. pylori-negative patients (P < 0.05; OR = 2.36, 95%CI: 0.12-1.06). In patients with H. pylori eradication obtained more than 6 mo earlier, the clinical pattern was similar to the H. pylori-negative group (P = 0.13; OR = 0.89, 95%CI: 0.77-6.51) and their symptoms were mainly typical with a distribution significantly different as compared to the H. pylori-positive group (P < 0.05; OR = 3.71, 95%CI: 0.83-16.47) (Figure 3).

The results of our study indicate that the presence of H. pylori infection in patients affected by GERD is associated with a greater frequency of atypical extraesophageal manifestations. In addition, GERD patients without H. pylori infection are preferentially affected by typical heartburn and regurgitation.

The relationship between GERD and H. pylori infection has been widely analyzed over the years but the question is still controversial. There are data supporting a protective role of H. pylori[12,13] as a consequence of gastric atrophy and hypochlorhydria from parietal cells destruction due to chronic H. pylori infection[14]. In the meanwhile, mild antral gastritis could be associated with hyperchlorydria and more severe GERD by reduction in the number of somatostatin-secreting D-cells with loss of negative feedback on gastric acid secretion[15]. Discordant results are also referred to the need of H. pylori eradication in GERD patients. In fact, some evidence suggests that eradication of the infection may be a risk factor for de-novo endoscopic esophagitis[16], whereas other studies report a low risk of gastric atrophy in patients with successful H. pylori eradication and undergoing long-term acid suppression with PPI[17].

Our study tried to look at this relationship from another perspective. We analyzed data of patients with GERD to determine whether the status of H. pylori infection affects the clinical pattern of reflux disease, without considering whether H. pylori could determine or prevent GERD. We found that the presence of gastric infection seems to facilitate the insurgency of atypical extraesophageal manifestations of reflux. It is unlikely that this association arose by chance as clinical pattern in GERD patients shows a clear trend towards atypical manifestations, directly correlated to H. pylori status. In fact, the symptoms of H. pylori-positive patients were predominantly atypical, a condition confirmed in the cases with very recent eradication. On the other hand, clinical aspects of patients successfully treated for H. pylori infection long time earlier resulted similar to those of H. pylori-negative patients. This suggests that the presence of bacterial infection has an action on GERD clinical pattern which is progressively reduced by the time the infection is eradicated. The major criticism of our results is that other factors, e.g., smoking, obesity and alimentary habits, could potentially affect the course of reflux disease and its clinical patterns[18]. However, these factors were unlikely to play a role in our population since we ruled out severe obese patients and recruited only slightly overweight patients, whose distribution was similar between subjects with typical and atypical symptoms. Furthermore, no correlation was found between smoking and clinical characteristics. Therefore, albeit considering the potential limit of a retrospective analysis, our data seem to indicate that life styles probably affect the characteristics of GERD less than H. pylori status.

In the present study, we did not identify the mechanisms through which H. pylori acts on the quality of reflux disease. Therefore, we can only make some speculations on the underlying conditions affecting different symptom patterns. First, the more severe degrees of esophagitis seem to be less correlated to H. pylori presence[19]; this could be one explanation for a major heartburn in our patients without infection. However, we can only partially confirm this assumption because in order to properly reduce the chance of confounding bias in our analysis, we excluded patients with Los Angeles grade C-D, known to have fewer reflux symptoms[20]. Second, the onset of symptoms (chronic cough, laryngitis or chest pain) seems strictly related to reflux episodes that extend proximally[21]. It could be that H. pylori-associated antral gastritis increases the release of gastrin concomitantly with higher acidity and increased volume of refluxate that more easily reaches the proximal site of the esophagus. Our study did not directly analyze the extension of refluxate as a single-channel pH-metric probe was used; however, there is some evidence on a greater frequency of proximal reflux episodes in pediatric patients with H. pylori infection[22] in good accordance with our results. Another possible explanation of the relationship between H. pylori and clinical appearance of GERD may be found in the modulation of afferent neural signals by H. pylori[23] an effect that seems related to ghrelin, a peptide with intense prokinetic activity on LES region[24]. It is well known that H. pylori-positive patients show low levels of circulating ghrelin, which tend to increase after bacterial eradication[25]. It is also demonstrated that patients with H. pylori infection have a lower LES tone and a reduced esophageal body motility[26]; therefore, it seems likely that a low plasma ghrelin concentration limits the clearance of acid inside the esophagus, thus facilitating proximal extension of reflux episodes.

A final consideration is that our present findings were made on the Caucasian population so it is reasonably difficult to extrapolate data from our study to predict what might happen to patients from other countries. In fact, the literature shows that the relationship between GERD and H. pylori seems completely different in East Asia compared to Western countries[27,28]. It is also well known that genetic predisposition can alter acid secretion[29] as well as visceral sensitivity of esophageal wall to acid[30]. Therefore, the interaction between host genetic factors and other agents, such H. pylori itself, could lead to different expression of GERD, but this aspect needs to be further clarified.

In conclusion, our findings suggest a role for H. pylori infection in the clinical pattern of GERD. Further analyses are required to evaluate if our results represent a potentially new strategy to modulate symptoms occurrence or indicate a simple association with no roles in the pathogenesis of GERD. Since it is already known that H. pylori does not affect the pH profile of patients with GERD[31], it seems appropriate to say that the relationship between H. pylori and pH appears more complex than previously thought. In fact, H. pylori is likely to interact with GERD, but when these two entities coexist, H. pylori seems to change the way of GERD symptoms appear rather than promoting or facilitating it.

The Authors thank Dr. Sonia Toracchio for reviewing the English style of the manuscript.

Although gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection represent two of the most common diseases of upper gastrointestinal tract, the relationship between these two entities is still not completely elucidated. The majority of studies tended to investigate whether H. pylori could facilitate the onset of GERD or protect against the disease. Similarly, the eradication of H. pylori in GERD patients is questionable.

The management of H. pylori infection is generally targeted to cure and prevent gastric and duodenal diseases. Diseases of the esophagus, reflux disease in particular, have been for decades considered to be of secondary importance in relation to H. pylori infection. In this study the presence of H. pylori is associated with a greater amount of atypical symptoms, whereas typical pattern is common in patients without the infection. Interestingly, the symptom pattern shows a trend from atypical to typical over time associated to H. pylori eradication, thus suggesting that the bacteria may have a role in the natural history of GERD.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study investigating the possible relationship between GERD and H. pylori from a different perspective, without considering the frequency of reflux disease after H. pylori eradication. In fact, the authors performed the study on a population of GERD patients for identifying two different symptom patterns that resulted related to H. pylori status.

This study could shed some light on why GERD patients refer different symptoms pattern. Hence there is a need for further investigation of H. pylori status not only in patients affected by gastroduodenal diseases, but also in patients with GERD.

pH-metry or pH-monitoring is the gold standard in the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. C13 urea breath test is the most accurate non-invasive test to diagnose H. pylori infection. Both tests could be affected by false negative results in case of concomitant use of antisecretory drugs.

This study is an important contribution to the literature regarding H. pylori and GERD, giving new information and possible explanations on the relationship between these two diseases.

P- Reviewer: Parker W, Shimatani T, Tandon R

S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Petroff OA, Burlina AP, Black J, Prichard JW. Metabolism of [1-13C]glucose in a synaptosomally enriched fraction of rat cerebrum studied by 1H/13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neurochem Res. 1991;16:1245-1251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hom C, Vaezi MF. Extra-esophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease: diagnosis and treatment. Drugs. 2013;73:1281-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Beji A, Vincent P, Darchis I, Husson MO, Cortot A, Leclerc H. Evidence of gastritis with several Helicobacter pylori strains. Lancet. 1989;2:1402-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dooley CP, Cohen H, Fitzgibbons PL, Bauer M, Appleman MD, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and histologic gastritis in asymptomatic persons. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1562-1566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 536] [Cited by in RCA: 499] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Glise H. Epidemiology in peptic ulcer disease. Current status and future aspects. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1990;175:13-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sidebotham RL, Baron JH. Hypothesis: Helicobacter pylori, urease, mucus, and gastric ulcer. Lancet. 1990;335:193-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Loffeld RJ, Willems I, Flendrig JA, Arends JW. Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinoma. Histopathology. 1990;17:537-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Helicobacter and cancer Collaborative Group. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 704] [Cited by in RCA: 749] [Article Influence: 31.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Graham DY. The changing epidemiology of GERD: geography and Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1462-1470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Moschos J, Kouklakis G, Lyratzopoulos N, Efremidou E, Maltezos E, Minopoulos G. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and Helicobacter pylori: lack of influence of infection on oesophageal manometric, 3-hour postprandial pHmetric and endoscopic findings. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2005;14:351-355. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Demeester TR, Johnson LF, Joseph GJ, Toscano MS, Hall AW, Skinner DB. Patterns of gastroesophageal reflux in health and disease. Ann Surg. 1976;184:459-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 541] [Cited by in RCA: 484] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lisiewicz J. Letter: Nowa nomenklatura antygenu Australia. Przegl Lek. 1975;32:363. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Haruma K. Review article: influence of Helicobacter pylori on gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 8:40-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sharma P, Vakil N. Review article: Helicobacter pylori and reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:297-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kamada T, Haruma K, Kawaguchi H, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Kajiyama G. The association between antral G and D cells and mucosal inflammation, atrophy, and Helicobacter pylori infection in subjects with normal mucosa, chronic gastritis, and duodenal ulcer. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:748-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Xie T, Cui X, Zheng H, Chen D, He L, Jiang B. Meta-analysis: eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with the development of endoscopic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:1195-1205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Matysiak-Budnik T, Laszewicz W, Lamarque D, Chaussade S. Helicobacter pylori and non-malignant diseases. Helicobacter. 2006;11 Suppl 1:27-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nocon M, Labenz J, Willich SN. Lifestyle factors and symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux -- a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:169-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chourasia D, Misra A, Tripathi S, Krishnani N, Ghoshal UC. Patients with Helicobacter pylori infection have less severe gastroesophageal reflux disease: a study using endoscopy, 24-hour gastric and esophageal pH metry. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2011;30:12-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bredenoord AJ. Mechanisms of reflux perception in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:8-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Forootan M, Ardeshiri M, Etemadi N, Maghsoodi N, Poorsaadati S. Findings of impedance pH-monitoring in patients with atypical gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2013;6:S117-S121. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Katra R, Kabelka Z, Jurovcik M, Hradsky O, Kraus J, Pavlik E, Nartova E, Lukes P, Astl J. Pilot study: Association between Helicobacter pylori in adenoid hyperplasia and reflux episodes detected by multiple intraluminal impedance in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78:1243-1249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Budzyński J, Kłopocka M, Bujak R, Swiatkowski M, Pulkowski G, Sinkiewicz W. Autonomic nervous function in Helicobacter pylori-infected patients with atypical chest pain studied by analysis of heart rate variability. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:451-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Thor PJ, Błaut U. Helicobacter pylori infection in pathogenesis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;57 Suppl 3:81-90. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Nwokolo CU, Freshwater DA, O’Hare P, Randeva HS. Plasma ghrelin following cure of Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 2003;52:637-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wu JC, Lai AC, Wong SK, Chan FK, Leung WK, Sung JJ. Dysfunction of oesophageal motility in Helicobacter pylori-infected patients with reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1913-1919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nam SY. Helicobacter pylori Has an Inverse Relationship With Severity of Reflux Esophagitis. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:209-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rajendra S, Ackroyd R, Robertson IK, Ho JJ, Karim N, Kutty KM. Helicobacter pylori, ethnicity, and the gastroesophageal reflux disease spectrum: a study from the East. Helicobacter. 2007;12:177-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chourasia D, Achyut BR, Tripathi S, Mittal B, Mittal RD, Ghoshal UC. Genotypic and functional roles of IL-1B and IL-1RN on the risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease: the presence of IL-1B-511*T/IL-1RN*1 (T1) haplotype may protect against the disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2704-2713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | de Vries DR, ter Linde JJ, van Herwaarden MA, Smout AJ, Samsom M. Gastroesophageal reflux disease is associated with the C825T polymorphism in the G-protein beta3 subunit gene (GNB3). Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:281-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gisbert JP, de Pedro A, Losa C, Barreiro A, Pajares JM. Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease: lack of influence of infection on twenty-four-hour esophageal pH monitoring and endoscopic findings. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:210-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |