Published online Nov 6, 2013. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v4.i4.120

Revised: October 9, 2013

Accepted: October 15, 2013

Published online: November 6, 2013

Processing time: 83 Days and 7.1 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the long-term effect of Endocinch treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

METHODS: After unblinding and crossover, 50 patients (32 males, 18 females; mean age 46 years) with pH-proven chronic GERD were recruited from an initial randomized, placebo-controlled, single-center study, and included in the present prospective open-label follow-up study. Initially, three gastroplications using the Endocinch device were placed under deep sedation in a standardized manner. Optional retreatment was offered in the first year with 1 or 2 extra gastroplications. At baseline, 3 mo after (re) treatment and yearly proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use, GERD symptoms, quality of life (QoL) scores, adverse events and treatment failures (defined as: patients using > 50% of their baseline PPI dose or receiving alternative antireflux therapy) were assessed. Intention-to-treat analysis was performed.

RESULTS: Median follow-up was 48 mo [interquartile range (IQR): 38-52]. Three patients were lost to follow-up. In 44% of patients retreatment was done after a median of 4 mo (IQR: 3-8). No serious adverse events occurred. At the end of follow-up, symptom scores and 4 out of 6 QoL subscales were improved (all P < 0.01 compared to baseline). However, 80% of patients required PPIs for their GERD symptoms. Ultimately, 64% of patients were classified as treatment failures. In 60% a post-procedural endoscopy was carried out, of which in 16% reflux esophagitis was diagnosed.

CONCLUSION: In the 4-year follow-up period, the subset of GERD patients that benefit from endoscopic gastroplication kept declining gradually, nearly half opted for retreatment and 80% required PPIs eventually.

Core tip: The long-term efficacy of the first commercially available endoluminal suturing device for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Endocinch, was evaluated. In the 4-year follow-up period, the subset of GERD patients that benefit from endoscopic gastroplication kept declining gradually. Up to 80% of patients again required acid-suppressive medication, making this endoscopic treatment procedure unsuccessful for the majority of GERD patients.

- Citation: Schwartz MP, Schreinemakers JRC, Smout AJPM. Four-year follow-up of endoscopic gastroplication for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2013; 4(4): 120-126

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v4/i4/120.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v4.i4.120

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common disorder with a substantial impact on quality of life and healthcare resources. Often, it is a chronic ailment that requires maintenance medical therapy. Important in the pathophysiology of GERD are a low basal tone of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), transient LES relaxations (TLESRs), and the presence of a hiatal hernia[1]. Laparoscopic fundoplication normalizes esophageal acid exposure by tightening the LES and repairing the hiatal hernia. Five years after surgery the overall patient satisfaction rate is still as high as 88% and only 14% requires daily antisecretory medication[2]. Indications for laparoscopic fundoplication are medication side-effects, incomplete relief of GERD symptoms despite medical treatment, or reluctance to take lifelong maintenance medication.

In the last two decades, the drawbacks inherent to a surgical procedure led to the development of endoscopic therapies for the treatment of GERD. These endoscopic procedures aimed to include the advantages of surgery, i.e., cure of the disease, while avoiding the complications of a surgical procedure. Various types of endoscopic procedures (thermal ablation, injection or implantation techniques and suturing devices) were designed and implemented. Several have already been withdrawn from the market because of safety concerns or lack of efficacy. In general, suturing devices raised highest expectations. They were designed to place stitches at or just below the esophagogastric junction, thereby creating gastroplications that tightened the LES. The Endocinch device is one of the first generation devices that is still available for commercial use.

Only a few studies have published long-term results (18-41 mo)[3-6]. In 2007 we completed a 3-mo, randomized, sham-controlled trial with a total follow-up duration of one year[7]. During short to medium-term follow-up, symptoms improved moderately, with no significant effects on acid exposure compared to sham. Like others, we had concerns about the durability of the sutures[8]. In a recent systematic review of randomized controlled trials and comparative studies on endoscopic treatments for GERD it was concluded that there is still not sufficient evidence to determine the long-term efficacy and safety of Endocinch[9]. The present study followed up on the 3-mo sham-controlled trial and aimed to prospectively evaluate its long-term efficacy and safety.

We conducted a prospective follow-up study until December 2008, which included all patients that were treated with Endocinch in the initial single-center, randomized trial that started in August 2003.

Approval for these studies was granted by the medical ethics committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands. It was obtained prior to the start of the original study and once more during the long-term follow-up period.

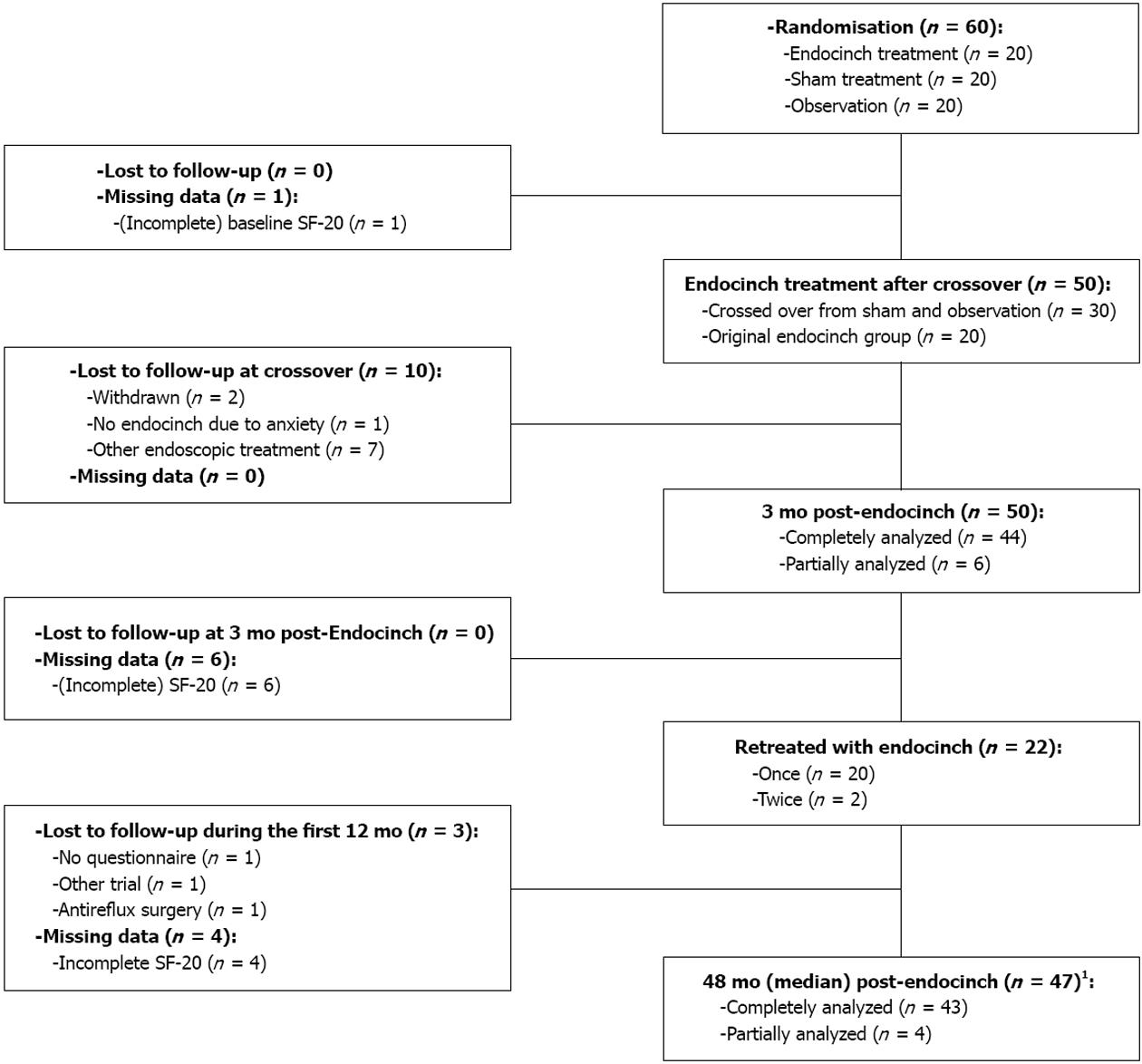

The single-center, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial included 60 patients that were allocated to 3 groups (Figure 1). Each group contained 20 patients. After 3 mo, the remaining untreated patients in the sham and observation groups were offered Endocinch treatment. 30 patients that agreed to cross over were successfully treated with Endocinch. Within the first year, patients that were classified as failures (defined as: unsatisfactory symptom response and/or < 50% reduction of their baseline dose of antisecretory medication) were offered retreatment. A total of 50 patients were included in the present follow-up study.

Endpoints were prospectively defined and included: GERD symptoms (heartburn and regurgitation), use of antisecretory medications, quality of life, adverse events, retreatment with Endocinch, and other reflux treatments. Patients were assessed on a yearly basis and these data were compared with pretreatment (baseline) and 3 mo post-treatment data.

The study objective was to establish whether the short-term effects would last. The hypotheses were that in the long-term: (1) symptoms; and (2) use of acid-suppressive medication would no longer be reduced compared with baseline values.

All randomized patients met the following inclusion criteria: persistent heartburn and/or regurgitation, and at least partial response to anti-secretory drugs and dependence on them for at least 1 year, unwillingness to take drugs lifelong, and esophageal pH results compatible with GERD diagnosis (> 5% of the time a pH < 4 or a 95% symptom association probability). Exclusion criteria were: < 18 years of age, severe esophageal motility disorder on manometry, hiatus hernia > 3 cm in length, history of thoracic or gastric surgery, reflux esophagitis grade C or D (LA classification), Barrett’s epithelium, severe comorbidity (cardiopulmonary disease, portal hypertension, collagen diseases, morbid obesity and coagulation disorders), use of anticoagulant or immunosuppressive drugs, or a history of alcohol or drug misuse.

Before enrollment in the 3-mo trial each patient’s eligibility was assessed. Patients underwent an upper endoscopy. The required daily dose of acid-suppressive medication to achieve optimal symptom control was recorded during a 1-mo run-in period. Subsequently, an esophageal manometry and ambulatory 24-h pH monitoring were performed after discontinuation of medication for 1 whole week (the results were published in a previous article)[7]. Prior to randomization, written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

The pre-treatment (baseline) questionnaire was completed at the end of the run-in period of the initial trial while patients were still off acid-suppressive medication. At 3 mo after randomization a second questionnaire was filled out (off medication). Esophageal manometry and ambulatory 24-h pH monitoring were repeated in the active and sham groups. Patients that were retreated underwent the same follow-up procedure. Additional reassessment took place at 6 and 12 mo. From 12 mo on, patients were reassessed with a yearly questionnaire. In accordance with intention to treat analysis, questionnaires from treatment failures were included.

Endoscopic suturing was carried out with the Endocinch suturing device (BARD Endoscopic Technologies, CR Bard, Billerica, MA, United States). The initial treatment aimed to create three gastroplications. During the first year of follow-up, patients with failure of therapy were offered retreatment consisting of one or two extra plications. All procedures were performed by the same endoscopist (MPS). The procedure was carried out using two video gastroscopes (type GIF-160, Olympus Nederland BV, Zoeterwoude, The Netherlands) and the endoscopic suturing device. After endoscopic placement of an esophageal overtube, two stitches were placed adjacent to one other, using the same thread. The first gastroplication was positioned about 1.5-2.0 cm below the squamocolumnar line along the lesser curvature. The second endoscope was used to create a plication by tightly pulling the sutures together and placing a suture anchor. A second plication was placed 1 cm above the first, and a third plication was placed at the level of the second along the greater curvature. All procedures were carried out under deep sedation with a combination of midazolam and pethidin administered intravenously. Oxygen saturation was monitored during the procedure. Afterwards, patients were observed for a period of 4 h during which blood pressure and heart rate were measured hourly.

GERD symptoms were scored utilizing a 6-point numeric scale measuring heartburn and regurgitation frequency (< 1 per month, once monthly, once weekly, once daily, 25 times per day, > 5 times daily) and a 4-point numeric scale measuring severity (not, mildly, moderately and very severe)[10]. The heartburn and regurgitation symptom scores were calculated by multiplying the frequency with the severity score. Quality of life assessments were done using the 20-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-20). The SF-20 consists of 20 items that assess the following 6 aspects: limitations in physical, role and social activities due to health problems, perception of mental and general health, and bodily pain. Each individual scale was transformed to a 100-point scale, 0 being the worst and 100 the best score, except in bodily pain perception in which a higher score stands for experiencing more pain.

The mean SD is provided when data are normally distributed, the median [interquartile range (IQR)] when the distribution is not normal.

The Wilcoxon signed-ranks test (nonparametric two-related samples) was used to test whether post-treatment values differed from baseline values. Whether two variables were related to each other was explored with logistic regression analysis. Differences and relations were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Baseline characteristics are provided in Table 1. Follow-up and missing data are presented in Figure 1. The median duration of follow-up was 48 mo (IQR: 38-52). Three patients were lost to follow-up in the first 12 mo. Between 12 and 48 mo nine patients reached the following predefined endpoints: 8 patients underwent antireflux surgery and one patient received an alternative endoscopic treatment. Four SF-20 questionnaires were either incomplete or missing. Therefore, 43 patients were analyzed completely, and 4 partially. Twenty-two (44%) patients were retreated with a mean of 1.4 plications, after a median period of 4 mo (IQR: 3-8). The median follow-up period after retreatment was 33 mo (IQR: 15-48). Twenty-eight patients (60%), all with persistent complaints, underwent a postprocedure upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. A mean of 0.73 stitches per patient were judged as functional. In twelve patients (24%) erosive reflux esophagitis was diagnosed (grade A, n = 7; grade B, n = 4; grade C, n = 1).

| Characteristic | Study group (n = 50) |

| Age (yr) | 46 (11) |

| Male sex | 64 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27 (4) |

| GERD symptom score2 | |

| Heartburn | 18 (15-20) |

| Regurgitation | 15 (12-18) |

| SF-20 score3 | |

| Physical function | 50 (17-75) |

| Role function | 100 (0-100) |

| Social function | 80 (60-100) |

| Mental health | 76 (60-88) |

| General health | 40 (18-70) |

| Bodily pain perception | 75 (50-75) |

| PPI dose (mg)4 | 40 (38-54) |

| Time pH < 4, % | 8.4 (6.1-12.7) |

| LES pressure (kPa) | 0.9 (0.3-1.5) |

| Hiatal hernia length (cm) | 1 (1-2) |

| Esophagitis grade A/B with or without Barrett’s metaplasia, n (%) | 38 |

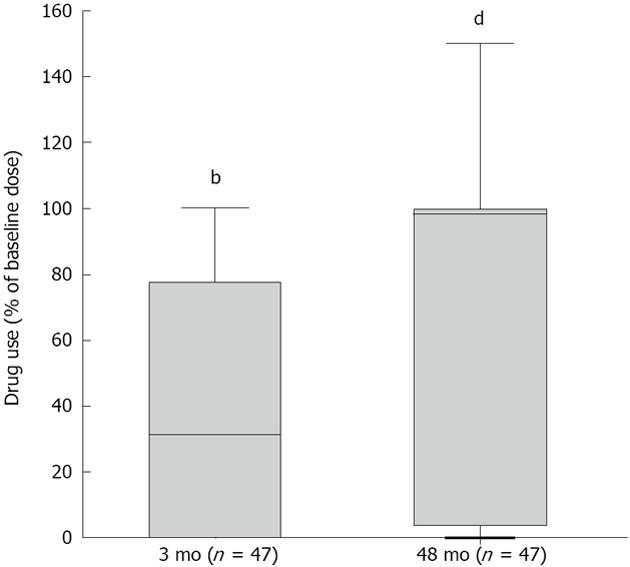

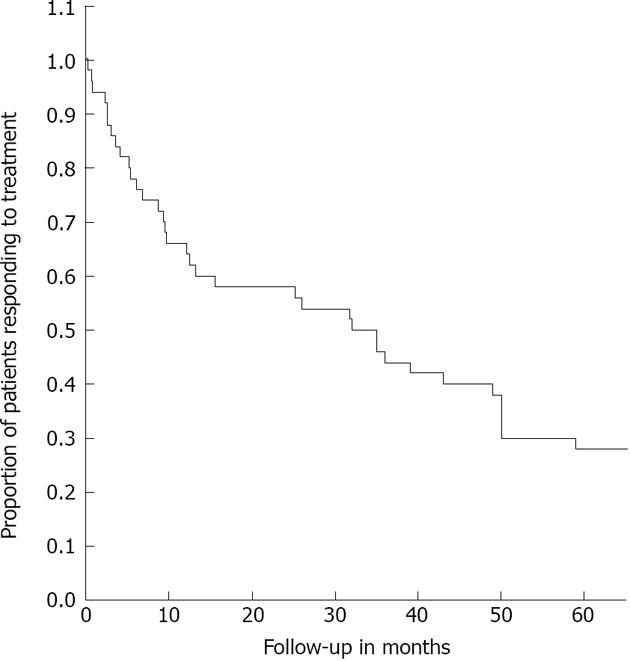

Compared with baseline, acid-suppressive medication use decreased significantly. At 3 and 48 mo the median doses were 31% (P < 0.001) and 97% (P < 0.001) of the baseline dose (Figure 2). Twenty percent were completely off acid-suppressive medication at the end of follow-up. At the end of follow-up, 18 (36%) of the 47 remaining patients used 50% or less of their baseline dose and had not received another treatment (Figure 3). As such, 64% were classified as treatment failures. If retreated patients were also considered to be treatment failures, irrespective of the effect of retreatment, the number of failures amounted to 36 patients (72%).

Compared with baseline, heartburn and regurgitation symptom scores were significantly decreased both at 3 mo and at the end of follow-up (Table 2). At 3 mo, heartburn and regurgitation scores decreased with 41% and 37%, respectively. At 48 mo, the heartburn score was reduced by 32% (P < 0.001) and the regurgitation score by 34% (P < 0.001).

| 3 mo | End of follow-up | P values1 | |||||

| Variable | Baseline | Absolute values | %2 | Absolute values | %2 | 3 mo | End |

| GERD symptom scores | |||||||

| Heartburn score3 | 16.4 (5.8) | 9.7 (7.6) | -41 | 11.2 (8.5) | -32 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Heartburn frequency | 5.0 (1.3) | 3.2 (2.1) | -35 | 3.4 (2.2) | -31 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Heartburn severity | 3.1 (0.9) | 2.3 (1.3) | -26 | 2.5 (1.4) | -20 | < 0.001 | < 0.003 |

| Regurgitation score3 | 15.6 (4.8) | 9.9 (7.8) | -37 | 10.2 (7.3) | -34 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Regurgitation frequency | 5.0 (1.1) | 3.3 (2.2) | -33 | 3.4 (2.0) | -32 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Regurgitation severity | 3.1 (0.8) | 2.2 (1.4) | -28 | 2.5 (1.2) | -20 | < 0.001 | < 0.002 |

| SF-20 scores4 | |||||||

| Physical health | 46.3 (34) | 64.0 (35) | 38 | 60.1 (35) | 30 | < 0.009 | < 0.02 |

| Role function | 59.2 (48) | 76.7 (39) | 31 | 73.9 (42) | 25 | < 0.023 | < 0.09 |

| Social function | 71.4 (32) | 81.3 (29) | 14 | 83.2 (28) | 16 | < 0.026 | < 0.006 |

| Mental health | 74.0 (18) | 73.2 (17) | -1 | 76.1 (15) | 3 | NS | NS |

| General health | 43.2 (27) | 56.2 (28) | 30 | 62.6 (28) | 45 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Bodily pain perception | 67.4 (26) | 48.9 (35) | -27 | 44.8 (34) | -34 | < 0.003 | < 0.001 |

At 3 mo, the SF-20 quality of life scores significantly improved in 5 of 6 subscales (P < 0.026, Table 2). Only the mental health subscale score had not changed significantly. At the end of follow-up, the same subscales remained significantly improved compared with baseline with the exception of role function.

At the end of follow-up, 17% of patients indicated that their GERD had completely been cured, 30% indicated that it had improved, 46% that it was unchanged and 7% that it had worsened.

One patient had a major hemorrhage immediately after the procedure and was hospitalized. After receiving endoscopic injection therapy to stop the bleeding and a blood transfusion, the patient made a speedy recovery. No other adverse events occurred either during treatments or follow-up.

Endoscopic treatment of GERD using Endocinch may improve GERD symptoms, decrease medication use and increase quality of life. However, after 4 years the treatment effect persists in less than half of treated patients. During the first follow-up year, the success rate progressively declined. This decline continued during the subsequent three years and it is likely that it will continue to do so. The percentage of treatment failures rose to 64%. At the end of follow-up, 47% of patients indicated that GERD was still improved compared to baseline and the GERD symptom scores and quality of life scores remained significantly improved. Yet, 80% required PPIs.

The limited number of adverse events in this follow-up study demonstrated that the procedure is safe in the long-term.

One study reported that treatment failure occurred in 80% of the patients during the 18-mo follow-up study (n = 70)[3]. Treatment failures were defined as in our study (unimproved heartburn symptoms or PPI dose exceeding 50% of the baseline dose), but patients were not retreated. Only 6% of patients succeeded to stay off PPIs after two years. The rate of 80% is comparable to the 72% found in the present study, when all retreated patients were also counted as treatment failures. However, in our study follow-up duration was much longer (48 vs 18 mo). Two other, multicenter studies from the US (n = 85) and Japan (n = 48) showed slightly better results with rates of 40% and 30%, respectively, of patients staying off PPI after two years[4,5]. These results indicate that 6% is relatively low and that our 20% accurately reflects the percentage of patients that remain off medication in the long-term (≥ 4 years).

The loss of functional plications, due to too superficial (i.e., not transmural) suturing, is generally accepted as the cause of loss of treatment effect[11,12]. In the present study no systematic endoscopic evaluation of the functionality of sutures was performed, because only treatment failures underwent a follow-up endoscopy. Hence, the actual proportion of patients with functional sutures is unknown. Among treatment failures a mean of only 0.73 sutures were still considered to be functional. Increasing the initial number of plications will probably only temporarily prolong the treatment effect, comparable to performing a second procedure, as was shown by the present study and others[6]. Also measurements to improve endurability, such as cauterization of the mucosa of a gastroplication, as evaluated in a 2-year follow-up study (n = 18), will not have a beneficial long-term effect[13]. Only modifications of the suturing technique can improve the depth of stitches, but up until now no improvements of the device have been made.

One can question whether the observed effect of treatment after 4 years is really the result of diminished esophageal acid exposure. After all, pH measurements were not repeated. Our initial study already showed that the improvement of esophageal acid exposure was not significantly greater than after sham treatment[7]. This is consistent with the results in other studies that found no significant differences or only marginal differences between baseline and post-procedure pH-values[3,6,14,15]. On the other hand, in our initial study a subgroup analysis (responders vs non-responders) made likely that the observed treatment effect was largely due to the reduction of esophageal acid exposure. We therefore believe that, although no repeated pH-metry was done, the effect after four years can also be attributed to esophageal acid reduction. It is highly unlikely that a placebo effect would still persist.

In summary, this is the longest prospective follow-up study after treatment with the endocinch procedure. It shows that GERD symptoms, medication use and quality of life improve in a subset of patients that gradually becomes smaller during follow-up. Endocinch can be carried out safely in an outpatient setting under conscious sedation. However, 44% had to undergo retreatment and eventually 80% needed PPIs again. In conclusion, in the long-term this procedure is not beneficial for the majority of GERD patients.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common, often chronic ailment with an important impact on quality of life and healthcare resources. Many patients require daily acid-suppressive medication or ultimately antireflux surgery. In recent years, several less invasive, endoscopic procedures have been developed. Endocinch is one of the first generation antireflux suturing devices, creating a barrier at or just below the gastro-esophageal junction against reflux.

Many studies, including a sham-controlled trial of our group, have demonstrated the short-term safety and efficacy of the Endocinch procedure on symptoms, but often failed to show significant improvements in esophageal acid exposure. Several follow-up studies have raised questions about medium-term efficacy. Prospective data exceeding two years of follow-up are scarce.

Loss of treatment effect could be due to loss of functional sutures, as was suggested by some researchers. Retreatment has been shown to (at least temporarily) improve results. In the present study, retreatment was also offered in case of early treatment failure and prospective follow-up duration was extended up to a median of four years.

The results of this study suggest that the endocinch procedure improves GERD symptoms, quality of life and reduces the use of acid-suppressive medication in only a subset of patients. A subset that gradually becomes smaller during four years of follow-up. Percent of 44 patients had to undergo retreatment and eventually 80% required acid-suppressive medications again. The study can conclude that in the long-term this procedure is not beneficial for the majority of GERD patients.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is a chronic disease in which the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) allows gastric acids to reflux into the esophagus leading to symptoms as heartburn and acid indigestion. Endocinch is a commercially developed endoscopic device designed to place stitches at or just below the esophagogastric junction, creating so-called ‘gastroplications’ that tighten the LES.

This is a well-designed prospective follow-up study in which the authors evaluated the long-term effect of endoluminal gastroplication with the Endocinch system for GERD. New important data have been provided that demonstrate that this procedure is not beneficial in the long-term for the majority of GERD patients.

P- Reviewers: Abdel-Salam OME, Gong YW, Hasanein P, Hou WH, Koulaouzidis A S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | van Herwaarden MA, Samsom M, Smout AJ. The role of hiatus hernia in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:831-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Draaisma WA, Rijnhart-de Jong HG, Broeders IA, Smout AJ, Furnee EJ, Gooszen HG. Five-year subjective and objective results of laparoscopic and conventional Nissen fundoplication: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2006;244:34-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schiefke I, Zabel-Langhennig A, Neumann S, Feisthammel J, Moessner J, Caca K. Long term failure of endoscopic gastroplication (EndoCinch). Gut. 2005;54:752-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chen YK, Raijman I, Ben-Menachem T, Starpoli AA, Liu J, Pazwash H, Weiland S, Shahrier M, Fortajada E, Saltzman JR. Long-term outcomes of endoluminal gastroplication: a U.S. multicenter trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:659-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ozawa S, Kumai K, Higuchi K, Arakawa T, Kato M, Asaka M, Katada N, Kuwano H, Kitajima M. Short-term and long-term outcome of endoluminal gastroplication for the treatment of GERD: the first multicenter trial in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:675-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Paulssen EJ, Lindsetmo RO. Long-term outcome of endoluminal gastroplication in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: effect of a second procedure. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:5-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schwartz MP, Wellink H, Gooszen HG, Conchillo JM, Samsom M, Smout AJ. Endoscopic gastroplication for the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a randomised, sham-controlled trial. Gut. 2007;56:20-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mahmood Z, Ang YS. Endocinch treatment for GORD: where it stands. Gut. 2005;54:1820-1821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen D, Barber C, McLoughlin P, Thavaneswaran P, Jamieson GG, Maddern GJ. Systematic review of endoscopic treatments for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Br J Surg. 2009;96:128-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bais JE, Bartelsman JF, Bonjer HJ, Cuesta MA, Go PM, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, van Lanschot JJ, Nadorp JH, Smout AJ, van der Graaf Y. Laparoscopic or conventional Nissen fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: randomised clinical trial. The Netherlands Antireflux Surgery Study Group. Lancet. 2000;355:170-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Torquati A, Richards WO. Endoluminal GERD treatments: critical appraisal of current literature with evidence-based medicine instruments. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:697-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Abou-Rebyeh H, Hoepffner N, Rösch T, Osmanoglou E, Haneke JH, Hintze RE, Wiedenmann B, Mönnikes H. Long-term failure of endoscopic suturing in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux: a prospective follow-up study. Endoscopy. 2005;37:213-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mosler P, Aziz AM, Hieston K, Filipi C, Lehman G. Evaluation of supplemental cautery during endoluminal gastroplication for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2158-2163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Montgomery M, Hakanson B, Ljungqvist O, Ahlman B, Thorell A. Twelve months' follow-up after treatment with the EndoCinch endoscopic technique for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1382-1389. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mahmood Z, Ang YS. EndoCinch treatment for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Digestion. 2007;76:241-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |