Published online Jun 5, 2025. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i2.101268

Revised: January 16, 2025

Accepted: April 25, 2025

Published online: June 5, 2025

Processing time: 266 Days and 21.9 Hours

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) symptoms are common in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), with systematic review reporting an overall pooled prevalence of 35-39% in patients with clinical remission. This subset of patients reports a reduced quality of life and increased anxiety and depression. A multi-strain probiotic (Symprove™, Symprove Ltd, Farnham, United Kingdom) has been shown to improve overall symptom severity in patients with IBS and is associated with decreased intestinal inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), but not in Crohn’s disease (CD).

To ascertain whether this multi-strain probiotic would be effective in an IBS/IBD overlap population.

The treatment of symptoms in the absence of inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a four-strain probiotic Symprove, containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus NCIMB 30174, Lactobacillus plantarum NCIMB 30173, Lactobacillus acidophilus NCIMB 30175 and Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 30176. The duration of the study was 3 months, at the end of which IBS-Symptom Severity Score (IBS-SSS) was repeated. Primary Endpoint was a 100-point reduction in IBS-SSS.

61 participants were randomized into the intention-to-treat analysis. 45% of patients receiving the active agent achieved the endpoint compared to 33% of those receiving placebo (P = 0.42). In UC, 50% of patients receiving placebo achieved the endpoint compared to 44% of those receiving the active agent (P = 1.00). In CD 45% of those receiving the active agent achieved the endpoint compared to 29% of those receiving placebo (P = 0.34). The mean change in IBS-SSS for patients receiving placebo was a reduction of 61 points, compared to a reduction in 90 points for patients receiving active agent (P = 0.31). There was no difference between the groups with regard to IBD outcomes.

Probiotics may represent a safe and effective means of addressing the unmet clinical need for symptom relief in patients with overlapping IBS and IBD, especially in those with CD.

Core Tip: A four-strain probiotic is well-tolerated in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) overlap and does not lead to adverse IBD related outcomes. Adequately powered studies are required to validate our observation of a trend towards better IBS outcomes in this group.

- Citation: Fennessy A, Doyle M, Boland A, Bourke R, O'Connor A. Four-strain probiotic exerts a positive effect on irritable bowel syndrome symptoms occurring in inflammatory bowel diseases in absence of inflammation (train-IBD trial). World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2025; 16(2): 101268

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v16/i2/101268.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i2.101268

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) such as Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are caused by a dysregulated T-cell immune response to enteric flora in a genetically susceptible host and affect an estimated five million people worldwide[1,2]. Clinical features of IBD include diarrhoea and chronic abdominal pain which are also associated with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) a more common condition which affects 11% of people globally, 30% of whom will seek medical help for their symptoms[3]. IBS symptoms are common in patients with IBD, with a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies reporting an overall pooled prevalence of 39% and 35% in patients in clinical remission[4]. This subset of IBD patients report a reduced quality of life and increased anxiety and depression[5]. These patients present significant challenges in terms of both diagnosis and management. The pathophysiology of IBS in IBD is multifactorial, with post inflammatory changes occurring in IBD likely contributing to symptom development including altered gastrointestinal motility, microbiome dysbiosis, medication use, prior surgery, impaired intestinal permeability, immune-system activation, and visceral hypersensitivity[6,7].

The diagnosis of IBS is dependent on meeting a set of criteria outlined by the Rome foundation which are characterized by abdominal pain related to defecation and a change in stool form and or frequency[8]. Given the degree of overlap between these symptoms and those seen in IBD it can be difficult for practising clinicians to accurately attribute the underlying mechanism behind symptoms which leads to a risk of both undertreating IBD and also overtreatment with unnecessary corticosteroid use and escalations of IBD treatment that are unlikely to bring relief to patients. In terms of treatment, IBS is considered best managed with a combination of dietary, lifestyle, psychological, and pharmacological interventions, which are tailored to the patient[9]. Guidelines are even more sparse for the IBS-IBD overlap group, with one commentary recommending guideline-based evaluation of concurrent infections or other causes for uncontrolled inflammation (i.e., bloody diarrhea, elevated leukocyte count, etc.) followed by guideline-based treatment of IBD and IBS individually[10].

This reflects the fact that unfortunately, there have been very few randomized controlled trials conducted on therapeutic interventions for overlapping Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in IBD, and IBD patients are generally specifically excluded from interventional studies in IBS. One study of dietary therapy with low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) diet reported a greater proportion of patients whose symptom scores improved and who had adequate relief of their IBS-type symptoms with the low-FODMAP diet than with a sham diet[11]. A multi-strain probiotic (Symprove™, Symprove Ltd, Farnham, United Kingdom) has been shown to lead to improvement in overall symptom severity in patients with IBS and associated with decreased intestinal inflammation in patients with UC, but not in CD and is well tolerated in both populations[12,13]. This however has never been assessed in IBD patients in randomized controlled trial format. We therefore attempted to ascertain whether this agent would be effective in an IBS/IBD overlap population.

The treatment of symptoms in the absence of inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot trial of a four strain probiotic Symprove (Symprove Ltd, Farnham, Surrey United Kingdom), a dietary supplement probiotic containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus NCIMB 30174, Lactobacillus plantarum NCIMB 30173, Lactobacillus acidophilus NCIMB 30175 and Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 30176 in the management in patients with IBD whose disease is in remission as evidenced by the absence of inflammation but have ongoing IBS symptoms. The study was conducted in the IBD clinic at Tallaght University Hospital. This is an academic medical center serving a population in southwest Dublin, Ireland, of approximately 400000. The hospital research ethics committee approved the protocol, and each study participant gave informed consent. Potential participants were screened by a consultant gastroenterologist at a hospital appointment.

Eligible participants were 18 years or older, with a primary diagnosis of either cd or UC. Patients had to meet Rome-IV criteria for an IBS diagnosis, with recurrent abdominal pain on average at least 1 day per week during the previous 3 months, which was associated with two or more of the following: Related to defecation, associated with a change in stool form, or associated with a change in stool frequency[8]. Exclusion criteria included active IBD, active steroid use, inability to read or understand English, previous intolerance to probiotics and pregnancy.

For entry into the study an IBS Symptom Severity Score (IBS-SSS) of 125 or more was required[14]. This is a validated questionnaire that assesses presence, severity, and frequency of abdominal pain, presence and severity of abdominal distension, satisfaction with bowel habit, and degree to which IBS symptoms are affecting, or interfering with, the individual’s life. Evidence of absence of mucosal inflammation was assessed by participants providing stool for quantitative Faecal Calprotectin (FC) analysis (Immundiagnostik, Bensheim, Germany), within 1 week of study entry. The cut-off of < 250 mg/g of stool FC was chosen, corresponding with the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization consensus on the use of FC to measure disease activity and as other investigators have used[5,15-17]. For added reassurance a serum C-reactive protein (CRP) measurement of < 5mg/L was also required in the same timeframe.

The study was approved by the local research ethics committee in November 2018, and data collection continued until June 2023. Participants were presented with an information sheet explaining the study in clinic and provided written informed consent. Study participants were randomized in a 2:1 active agent to placebo ratio manually by a blinded non-clinical member of the study team. The duration of the study was 3 months, at the end of which IBS-SSS was repeated, as was CRP and FC. Chart review was undertaken to look for clinical information such as steroid use, surgery or escalation in IBD therapy. Blinding of allocation to treatment was maintained until the study was completed. Compliance was assessed at the end of the study when patients were asked to whether they had taken 80% or more of the agent they were given.

Symprove (Symprove Ltd, Farnham, Surrey United Kingdom) is a four-strain probiotic as outlined earlier constituted in a water-based suspension of barley extract. Dosage is 70 mL corresponding to more than 10000000000 live bacteria. The placebo was an identical liquid in appearance and taste, containing water and flavoring and was provided in identical packaging supplied by the manufacturers identified by a trial batch and code number only. Patients were asked to refrigerate the agent between 2 and 7 °C and to self-administer one full 70 mL dose on an empty stomach. Subjects were asked to have nil by mouth for 20 minutes after the administration.

The primary outcome of the study was a 100-point drop in IBS-SSS post treatment. The stringent endpoint used here reflects the difficulty of treating this particular cohort to ensure a meaningful result. Secondary Outcomes were overall magnitude of change in IBS-SSS, adherence to treatment, adverse events and negative IBD outcomes including biochemical flare, steroid treatment or escalation of maintenance therapy. Mild, moderate, or severe IBS symptoms were classified by scores of 75-174, 175-299, or 300-500, respectively.

Regarding the primary endpoint significance was estimated using a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test. Regarding the secondary endpoint of difference in IBS-SSS from baseline significance was estimated using an independent samples t-test using GraphPad Prism version 10.0. (Graphpad). The efficacy measures were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis which included all patients randomized to any treatment. A P value of at or below 0.05 was considered as a statistically significant result. Given the pilot nature of the study and the fact that so little evidence exists to guide us on the topic of IBS treatment in IBD our power calculation (40 patients in treatment group) was calculated on the assumption that 60% of patients would respond with a 30% response in the placebo group which gives an 80% power at a 5% significance level.

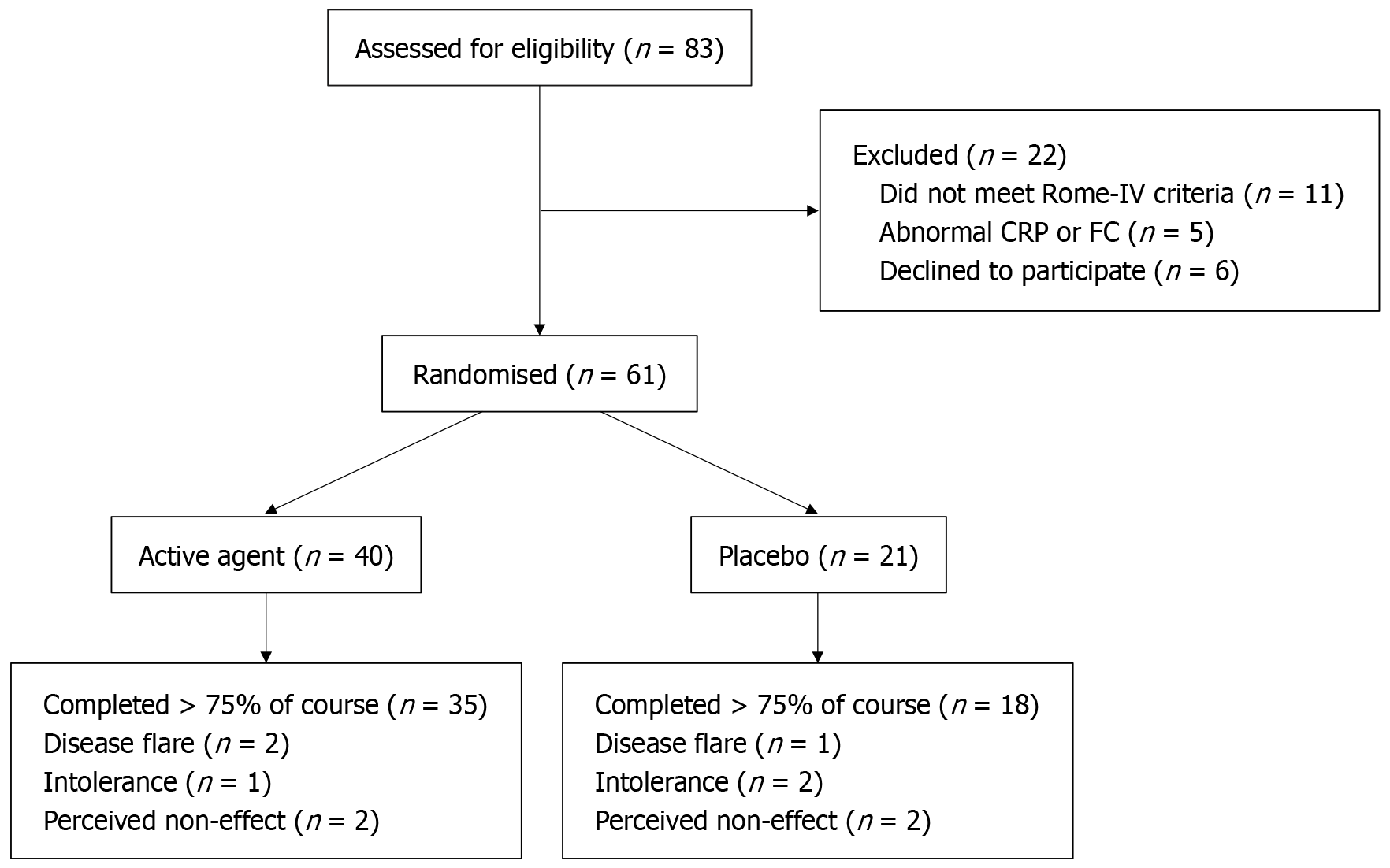

Eligible participants were recruited between October 29th, 2018, and February 27th, 2022. Study participants were screened by during a visit to the IBD clinic at the hospital and underwent their pre- and post-treatment assessments in the same clinic. Figure 1 indicates the flow of study participants through recruitment, randomisation and analysis. Subjects went forward for screening if they had ongoing gastrointestinal symptoms and FC < 250 mg/g and CRP < 5 mg/L, both of which are routinely checked biannually at the IBD clinic. 83 were sent forward for screening and 16 were excluded because of ineligibility, 5 of whom had developed abnormal FC or CRP by the time of screening visit and 11 did not meet Rome-IV criteria. 6 patients met criteria but declined to participate. 61 participants (73.5%) were enrolled and randomised into the control or treatment groups and were included in the ITT analysis. 82.8% of patients (n = 53) completed more than 75% of the course of treatment as evidenced by three or fewer empty bottles of product or placebo. 12.5% of patients (n = 5) in the active agent arm failed to complete treatment, 2 discontinued due to a disease flare, 1 due to intolerance (nausea), 2 due to perceived non effect. 14.3% of patients (n = 3) in the placebo agent arm failed to complete treatment, 1 discontinued due to a disease flare, 2 due to intolerance (1 nausea, 1 constipation) (Figure 1).

Table 1 indicates the demographic and clinical features of the total study population and of the treatment allocation groups. The demographic profile of the study participants was women in their early 40s. The clinical profile shows CD of long duration accompanied by IBS symptoms of moderate to severe intensity. There was a non-significant tendency towards more severe symptoms in the group randomized to placebo with 57.1% vs 35.0% (P = 0.11) being classified as severe and having higher mean IBS-SSS 308 vs 272 (P = 0.25). The placebo group also had higher rates of previous intestinal resection in the placebo than the active agent group, although the active agent group had higher use of biologic medications, none of which were statistically significant. The only clinical factor meeting statistical significance was a tendency to longer disease duration in the placebo group (18 vs 10 years, P-value < 0.01) (Table 1).

| Total sample (n = 61) | Active treatment (n = 40) | Placebo (n = 21) | P value | |

| Age | 42 ± 12 | 40 ± 11 | 45 ± 13 | 0.12 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 43 (70.5) | 28 (70.0) | 15 (71.4) | 1.00 |

| Male | 18 (29.5) | 12 (30.0) | 6 (28.6) | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| CD | 44 (72.1) | 31 (77.5) | 13 (61.9) | 0.24 |

| UC | 17 (27.9) | 9 (22.5) | 8 (38.1) | |

| Disease duration | 13 ± 10 | 10 ± 7 | 18 ± 12 | < 0.01 |

| Previous resection | 16 (26.2) | 8 (20.0) | 8 (38.1) | 0.14 |

| Biologic use | 40 (65.6) | 28 (70.0) | 12 (57.1) | 0.39 |

| IBS severity | ||||

| IBS-SSS at baseline | 285 ± 115 | 272 ± 129 | 308 ± 77 | 0.25 |

| Mild | 9 (14.8) | 6 (15) | 3 (14) | 0.11 (severe vs mild-moderate) |

| Moderate | 26 (42.6) | 20 (50.0) | 6 (28.6) | |

| Severe | 26 (42.6) | 14 (35.0) | 12 (57.1) |

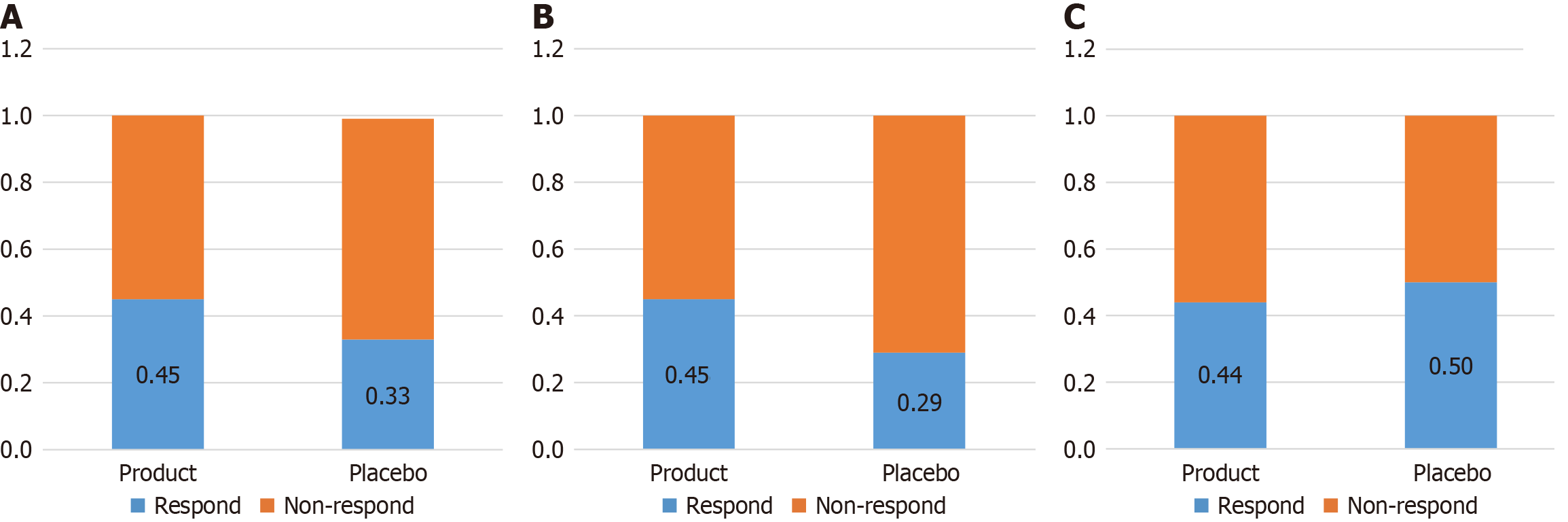

61 participants (73.5% of those eligible) were enrolled and randomized either into the active agent group (n = 40) or placebo group (n = 21). Overall 45% of patients receiving the active agent achieved the study end point compared to 33% of those receiving placebo (P = 0.42). Separating patients with CD from those with UC, 50% of patients with UC receiving placebo achieved the endpoint compared to 44% of those receiving the active agent (P = 1.00), however in CD 45% of those receiving the active agent achieved the endpoint compared to 29% of those receiving placebo (P = 0.340). This is outlined in Figure 2.

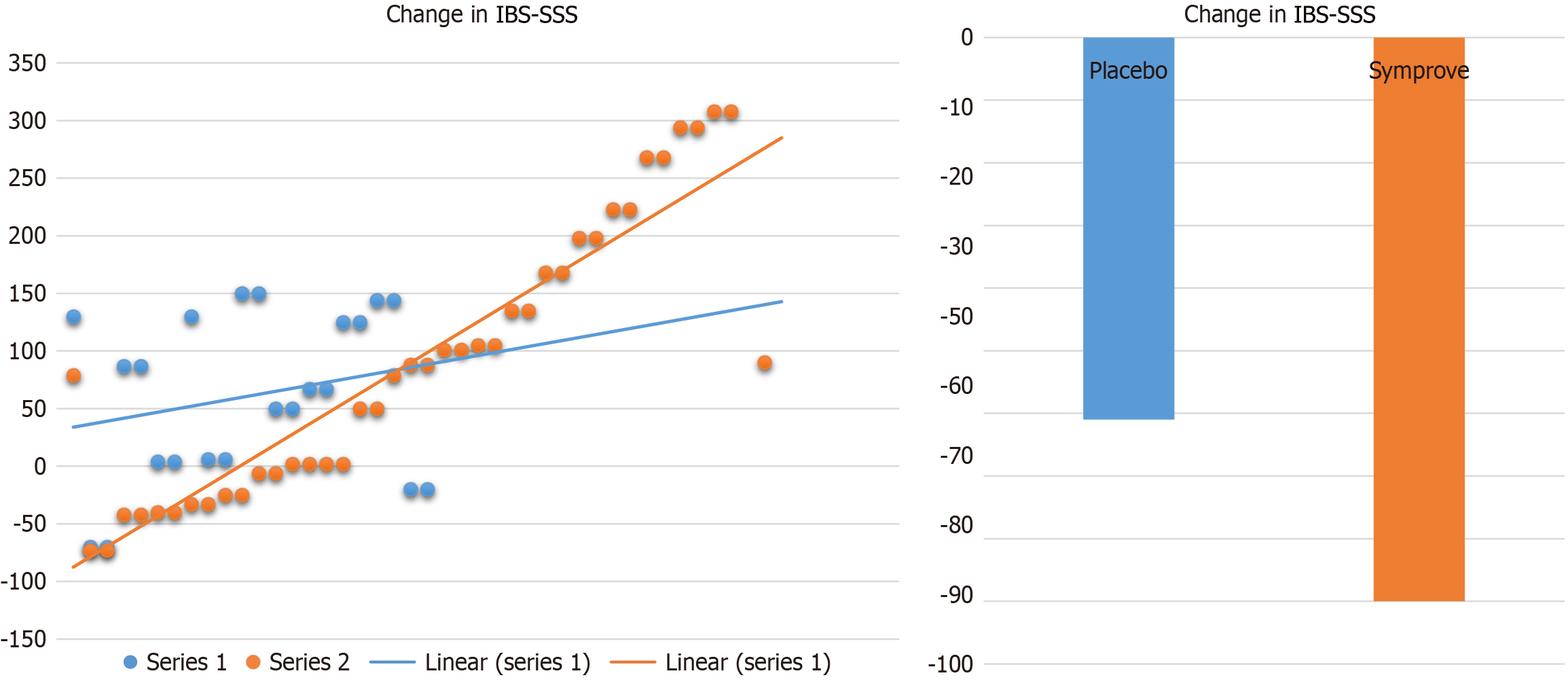

In terms of the magnitude of improvement, the mean change in IBS-SSS for patients receiving placebo was a reduction of 61 points, compared to a reduction in 90 points for patients receiving active agent (P = 0.31). This is outlined in Figure 3.

IBD-related outcomes are outlined in Table 2. 16.4% (n = 10) of patients in the study either experienced a disease flare or required escalation of disease modifying therapy or a steroid prescription. These were equally distributed between the placebo and active agent group and while there was a tendency to more IBD activity in the placebo group (23.8% vs 12.5%) this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.29) (Table 2).

| Total sample (n = 61) | Active agent (n = 40) | Placebo (n = 21) | P value | |

| Biochemical flare | 8 (13.1) | 4 (10) | 4 (19.0) | 0.43 |

| Steroid use or escalation of therapy | 8 (13.1) | 4 (10) | 4 (19.0) | 0.43 |

| Biochemical flare or steroid or escalation of therapy | 10 (16.4) | 5 (12.5) | 5 (23.8) | 0.29 |

In this cohort of patients with IBD and ongoing IBS symptoms in the absence of objective inflammation a trend towards improvement in IBS symptomatology is noted in patients with IBD receiving a four-strain probiotic compared to placebo, that does not reach statistical significance. Prior studies have demonstrated the potential for probiotics in the mana

Any evaluation of the role of probiotics in gastrointestinal symptoms must bear in mind that the benefits conferred may be strain-specific, but the same multi-strain probiotic from this study when used on asymptomatic patients with active inflammation was associated with decreased intestinal inflammation in patients with UC, but not in CD[13]. The fact that in contrast to this, response to probiotic in these patients for the treatment of IBS is equal lends further support to the idea that IBD patients with ongoing IBS symptoms in the absence of inflammation do represent a distinct subcategory of patients with IBD, rather than being a marker of occult inflammation[21]. These patients have previously been demonstrated as having a distinct psychological profile with significantly higher Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score scores for both anxiety and depression and somatization scores in patients with true IBS symptoms than patients with quiescent IBD or occult inflammation[5].

While the role of the brain–gut axis in the development and perception of symptoms in IBS is reasonably well understood, its role in IBD is significantly less well studied, leaving clinicians with significant unmet needs in how to manage the symptoms of the condition. A large United States cohort of over 6000 participants with both CD and UC and a concurrent IBS diagnosis found that IBD-IBS was associated with greater health care use in both primary and secondary care and that even when those with IBD activity were excluded, it was a significant independent factor associated with anxiety, depression, fatigue, pain, disturbed sleep, and decreased social satisfaction[22]. Therefore a significant imperative exists to identify suitable treatments for this group. There are however, no clinical trials of most of the typical treatments used for IBS (e.g., antispasmodics, peppermint oil, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or tricyclic antidepressants) for patients with IBD-IBS overlap.

Several studies have examined the role of dietary managements[11,23-25]. In one such, a total of 52 patients were randomized to either the low-FODMAP diet or a sham diet for 4 weeks and found no significant difference after 4 weeks in change in overall IBS severity scores, but significant improvements in specific symptom scores and numbers reporting global adequate symptom relief with a mean reduction in IBS-SSS of 67 points[11]. Our study compares favorably to this with an average reduction in IBS-SSS of 90 points in the active treatment group. We used a very stringent endpoint of a 100-point reduction in IBS-SSS to define treatment success given the complexity in this particular group and found a placebo response of 33%. A meta-analysis of placebo effect in IBS randomized controlled trials overall identified a placebo response for abdominal pain of 34.6% and stool response of 30.1% which vindicates our choice of this endpoint[26]. The overall risk reduction of 12% for product vs placebo implies a number needed to treat of 8 which again compares reasonably well with the overall IBS population where a meta-analysis of the effect of fibre, antispasmodics, and peppermint oil in the treatment of symptoms found Number Needed To Treat of between 4 and 6[27]. Ultimately however, it is our contention that multidisciplinary care and consultation is likely to yield the best results for these patients. The use of probiotics will play a part in this, as will engagement with suitably trained dietitians, psychologists, nurse specialists and other ancilliary supports that help provide the best care for patients with disorders of gut-brain interaction.

There are several weaknesses in the trial. The Coronavirus pandemic complicated and delayed the recruitment and follow-up process. The numbers of participants was inadequate. We believe our trial did not show significance in IBD because it was underpowered, rather than fully recruited but not effective. The strength of the placebo response may point towards a placebo bias in these patients. In addition, the fact that patients were given free access to an expensive food supplement may have enhanced further the placebo effect and led to a confirmation bias. Another bias at play may be the fact that only patients in remission were included. In reality, IBS symptoms affect patients with active IBD as well, and possibly to an even greater extent. Excluding these patients introduces a bias, and equally so, reduces the generalisability of the findings to the broader IBD population.

In summary, we present a randomized controlled trial of a four-strain probiotic agent for patients with ongoing IBS symptoms in the context of quiescent IBD which was well-tolerated. Adherence to therapy was good and no increase in IBD-related adverse outcomes were noted. Response to what was a stringent endpoint was good and comparable both in terms of efficacy and the placebo response to published trials in the broader IBS population which may point the way towards adequately powering the further, larger studies that are required to validate or refute these findings. Probiotics may represent a safe and effective means of addressing the unmet clinical need for symptom relief in patients with overlapping IBS and IBD.

| 1. | Wang R, Li Z, Liu S, Zhang D. Global, regional and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e065186. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | de Souza HS, Fiocchi C. Immunopathogenesis of IBD: current state of the art. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:13-27. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Canavan C, West J, Card T. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:71-80. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Halpin SJ, Ford AC. Prevalence of symptoms meeting criteria for irritable bowel syndrome in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1474-1482. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Gracie DJ, Williams CJ, Sood R, Mumtaz S, Bholah MH, Hamlin PJ, Ford AC. Negative Effects on Psychological Health and Quality of Life of Genuine Irritable Bowel Syndrome-type Symptoms in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:376-384.e5. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Walker C, Boland A, Carroll A, O’connor A. Concurrent functional gastrointestinal disorders in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Front Gastroenterol. 2022;1:959082. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Nigam GB, Limdi JK, Vasant DH. Current perspectives on the diagnosis and management of functional anorectal disorders in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1756284818816956. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Drossman DA, Hasler WL. Rome IV-Functional GI Disorders: Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1257-1261. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Camilleri M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Review. JAMA. 2021;325:865-877. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Kamal A, Padival R, Lashner B. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: What to Do When There Is an Overlap. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:2479-2482. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Cox SR, Lindsay JO, Fromentin S, Stagg AJ, McCarthy NE, Galleron N, Ibraim SB, Roume H, Levenez F, Pons N, Maziers N, Lomer MC, Ehrlich SD, Irving PM, Whelan K. Effects of Low FODMAP Diet on Symptoms, Fecal Microbiome, and Markers of Inflammation in Patients With Quiescent Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:176-188.e7. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Sisson G, Ayis S, Sherwood RA, Bjarnason I. Randomised clinical trial: A liquid multi-strain probiotic vs. placebo in the irritable bowel syndrome--a 12 week double-blind study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:51-62. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Bjarnason I, Sission G, Hayee B. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a multi-strain probiotic in patients with asymptomatic ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Inflammopharmacology. 2019;27:465-473. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:395-402. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Rogler G, Aldeguer X, Kruis W, Lasson A, Mittmann U, Nally K, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Schoepfer A, Vatn M, Vavricka S, Logan R. Concept for a rapid point-of-care calprotectin diagnostic test for diagnosis and disease activity monitoring in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: expert clinical opinion. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:670-677. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | D'Haens G, Ferrante M, Vermeire S, Baert F, Noman M, Moortgat L, Geens P, Iwens D, Aerden I, Van Assche G, Van Olmen G, Rutgeerts P. Fecal calprotectin is a surrogate marker for endoscopic lesions in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2218-2224. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Targownik LE, Sexton KA, Bernstein MT, Beatie B, Sargent M, Walker JR, Graff LA. The Relationship Among Perceived Stress, Symptoms, and Inflammation in Persons With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1001-12; quiz 1013. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | So D, Quigley EMM, Whelan K. Probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease: review of mechanisms and effectiveness. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2023;39:103-109. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Kaur L, Gordon M, Baines PA, Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Sinopoulou V, Akobeng AK. Probiotics for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;3:CD005573. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Limketkai BN, Akobeng AK, Gordon M, Adepoju AA. Probiotics for induction of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;7:CD006634. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Keohane J, O'Mahony C, O'Mahony L, O'Mahony S, Quigley EM, Shanahan F. Irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a real association or reflection of occult inflammation? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1788, 1789-94; quiz 1795. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Abdalla MI, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD, Martin CF, Chen W, Anton K, Long MD. Prevalence and Impact of Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Irritable Bowel Syndrome on Patient-reported Outcomes in CCFA Partners. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:325-331. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Gearry RB, Irving PM, Barrett JS, Nathan DM, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Reduction of dietary poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates (FODMAPs) improves abdominal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease-a pilot study. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3:8-14. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Prince AC, Myers CE, Joyce T, Irving P, Lomer M, Whelan K. Fermentable Carbohydrate Restriction (Low FODMAP Diet) in Clinical Practice Improves Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1129-1136. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Pedersen N, Ankersen DV, Felding M, Wachmann H, Végh Z, Molzen L, Burisch J, Andersen JR, Munkholm P. Low-FODMAP diet reduces irritable bowel symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:3356-3366. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Barberio B, Savarino EV, Black CJ, Ford AC. Placebo Response Rates in Trials of Licensed Drugs for Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Constipation or Diarrhea: Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:e923-e944. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |