Published online Sep 5, 2024. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v15.i5.97330

Revised: July 25, 2024

Accepted: August 2, 2024

Published online: September 5, 2024

Processing time: 97 Days and 22.3 Hours

Functional constipation (FC) is a common gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal pain and bloating, which can greatly affect the quality of life of patients. Conventional treatments often yield suboptimal results, leading to the exploration of alternative therapeutic approaches.

To evaluate the efficacy of KiwiBiotic in the management of FC and related symp

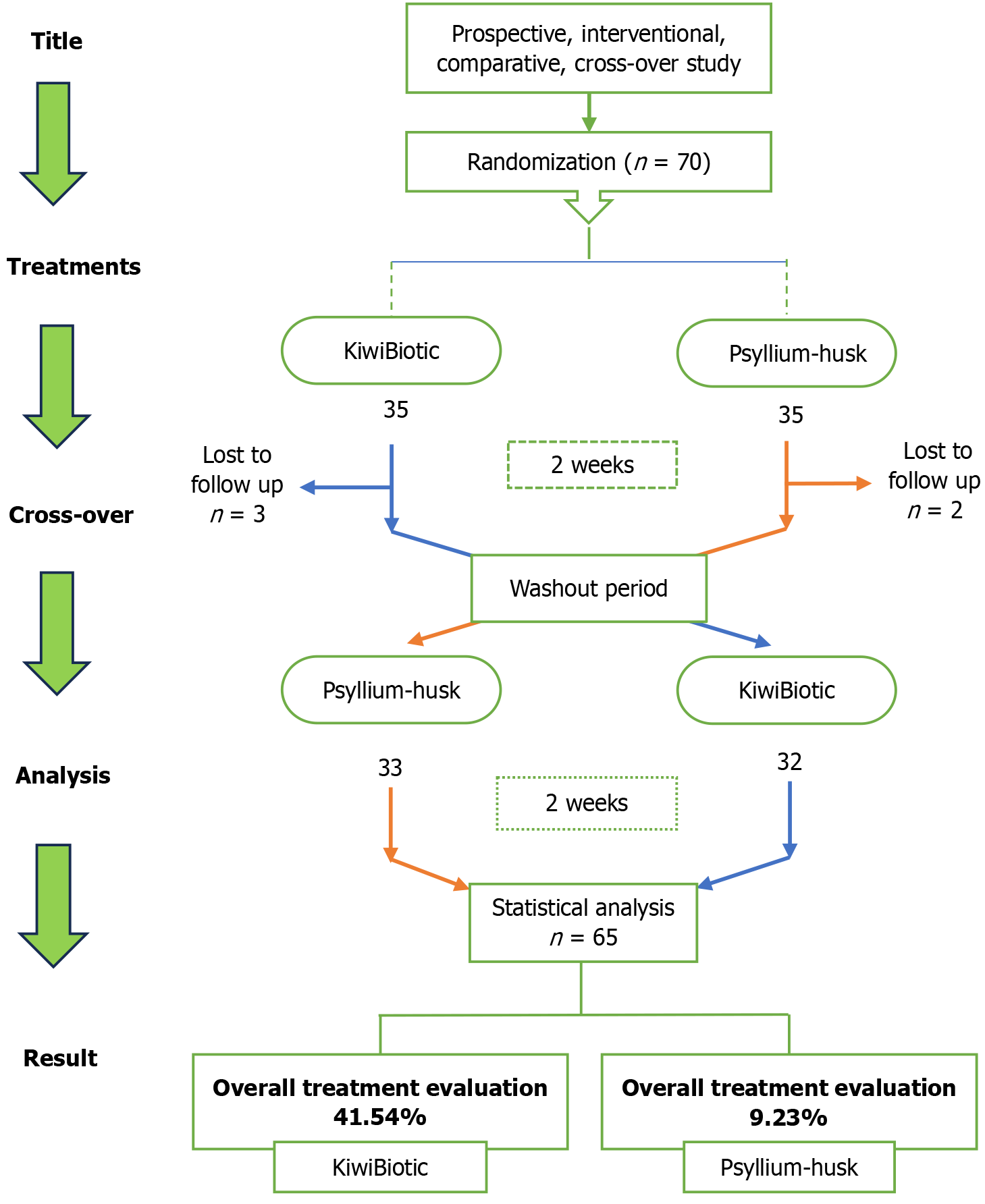

This prospective, interventional, single-center, crossover study compared the safety and effectiveness of KiwiBiotic®vs psyllium husk in managing FC, ab

Seventy participants were enrolled, 32 of whom received KiwiBiotic followed by psyllium husk, and 33 received KiwiBiotic. KiwiBiotic showed superiority over psyllium husk in alleviating abdominal pain and bloating, as evidenced by significantly lower mean scores. Furthermore, KiwiBiotic resulted in more than 90.0% of patients experiencing relief from various constipation symptoms, while psyllium husk showed comparatively lower efficacy.

KiwiBiotic is an effective treatment option for FC, abdominal pain, and bloating, highlighting its potential as a promising alternative therapy for patients with FC and its associated symptoms.

Core Tip: Functional constipation (FC) significantly affects the quality of life of patients due to symptoms such as abdominal pain and bloating. Conventional treatments often fail, necessitating alternative therapies. Phytotherapeutic product KiwiBiotic has emerged as a promising alternative treatment for FC, abdominal pain, and bloating, offering superior efficacy, improved quality of life, and higher patient satisfaction than conventional options such as psyllium husk. Its effectiveness in symptom relief, demonstrated in more than 90% of patients, highlights its potential as a safe and comprehensive therapeutic option.

- Citation: Porwal AD, Gandhi PM, Kulkarni DK, Bhagwat GB, Kamble PP. Effect of KiwiBiotic on functional constipation and related symptoms: A prospective, single-center, randomized, comparative, crossover study. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2024; 15(5): 97330

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v15/i5/97330.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v15.i5.97330

Constipation is characterized by a decrease in the regularity of bowel movements or challenges in stool discharge. Symptoms commonly linked to this condition include hard stool, effortful strain, blockage sensation in the anal region, sense of incomplete bowel emptying, abdominal pain, and swelling[1]. This condition is divided into several categories, including functional, chronic idiopathic, and secondary constipation, all of which are distinguished by specific causes and clinical characteristics[2]. Functional constipation (FC) is a type of functional bowel disorder characterized by symptoms such as difficulty in defecating, infrequent bowel movements, or a feeling of incomplete bowel evacuation, with a prevalence of approximately 20% in adults[3,4]. Constantly constipated patients are associated with higher all-cause mortality and are at higher risk of mental health issues[5]. Risk factors for constipation include living conditions, dietary patterns, and unhealthy lifestyle choices[6].

Many people with FC resort to self-medication, which can affect the ideal timing of treatment and worsen their condition[7]. Due to variables such as decreased mobility, polypharmacy, and coexisting medical diseases, older people frequently have poor tolerance to non-pharmacological treatments such as lifestyle changes (e.g., exercise, high-fiber foods, and increased fluid intake)[8,9]. The underlying causes of FC are complex and involve multiple factors, including genetics. However, specific genes linked to this condition have not been identified. This absence of genetic markers leads some experts to propose that lifestyle and environmental influences within certain families could actually explain the observed patterns of constipation rather than hereditary factors[10]. The quality of life and psychological well-being of patients are significantly affected by repeated consultations, unnecessary investigations, and prolonged disease duration, which impose substantial financial burdens and pose considerable challenges in managing the condition[11].

Bulk-forming drugs are usually recommended as first-line treatment for constipation. These substances absorb water to increase the amount of feces and facilitate bowel movements. Adequate fluid intake is crucial when using bulk-forming medications to prevent bloating and, more importantly, reduce the likelihood of intestinal obstruction associated with dehydration[12]. In addition to bulk-forming medications, various drugs are used to treat constipation, including stimulants, stool softeners, and osmotic agents, depending on the severity of the condition[13-16]. Although conventional treatment is established and considered safe, it often does not provide satisfactory improvement in many patients, leading them to explore alternative therapeutic approaches[17]. Complementary and alternative medicines are gaining popularity due to their perceived safety and efficacy[18].

Consequently, there is an incentive to consider medications from complementary and alternative medical systems as potential treatment options for constipation. The formulation used in the current study, KiwiBiotic, was in liquid form and contained mainly kiwi pulp. This study aimed to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of KiwiBiotic compared to psyllium husk in the management of FC, abdominal pain, and bloating.

In this prospective, interventional, single-center, crossover study, participants diagnosed with FC were randomly assigned to groups in a 1:1 ratio. The trial was carried out at Healing Hands Clinic Pvt. Ltd., DP Road, Pune, Ma

The phytotherapeutic products, KiwiBiotic® and psyllium husk, were provided by Healing Hands and Herbs Pvt. Ltd., located in Pune, India, www.myhealinghands.in. KiwiBiotic was manufactured and marketed by Healing Hands and Herbs Pvt., Ltd.

Eligible participants were aged ≥ 18 years and diagnosed with FC, abdominal pain, or bloating according to the ROME IV criteria[19,20]. Participants are only included if the participants, their parents, or any legal guardian are willing to give their written informed consent or parental consent or consent form and if they are willing to strictly adhere to the investigator’s prescription. Patients were excluded if they had taken any medication that could interfere with the action of the medication before or during the start of the study. Furthermore, patients with pre-existing conditions that could compromise their safety or participation in the study were excluded.

Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive KiwiBiotic (50 mL orally twice daily) during period 1, followed by psyllium husk (1.82 g orally once daily) during period 2 (sequence 1), or psyllium husk during period 1, followed by KiwiBiotic during period 2 (sequence 2).

During the screening visit, the participants underwent assessments of their medical history and concomitant medications, along with physical examinations. The patients were randomly assigned to undergo two treatment periods of 14 days each, with a 14-day washout period between them. Vital signs, such as body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and respiratory rate, were assessed at each visit (days 0, 14, 28, 42, and 49) to ensure safety. The last follow-up visit, scheduled for day 49, aimed to confirm whether symptoms had recurred after the completion of the final treatment on day 42 (Figure 1). Participants were assessed for efficacy following the administration of the study products. This includes an assessment of FC according to the ROME IV criteria and an assessment of abdominal pain and bloating using a visual analog scale. At the end of each treatment period, quality of life was evaluated using the gastrointestinal quality of life questionnaire, and the overall treatment evaluation score was measured.

The primary efficacy endpoint was changes in FC symptoms, abdominal pain, and bloating. Secondary endpoints included the assessment of gastrointestinal quality of life using the gastrointestinal quality of life index (GIQLI), overall treatment evaluation scores by physicians, and incidence of adverse events, with data collected up to the 5th visit.

The trial sample size was determined to detect a standardized difference of 0.6 with 90% power and significance level α = 5%, which represents a 10% dropout rate, resulting in the recruitment of 70 participants. Demographics and baseline characteristics of the participants were summarized using mean, SD, and range for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Equivalence tests were conducted to compare abdominal pain and abdominal bloating at a significance level of 5%. For the symptoms of FC, we used a two-sided McNemar’s test, with a P-value < 0.05 indicating statistical significance. Two-sided paired t-tests were used to compare the overall GIQLI scores and their domains.

Between October 20, 2023 and February 12, 2024, a total of 70 patients were recruited. Of the initial 70 patients, 35 were randomly assigned to receive KiwiBiotic during period 1, followed by psyllium husk during period 2; the remaining 35 received psyllium husk during period 1, followed by KiwiBiotic during period 2. In this study, 44 females (62.86%) and 26 males (37.14%) were enrolled, with a mean age of 43.61 years (SD = 13.41). The average weight of all participants was 60.65 kg (SD = 8.09) and the average height was 163.42 cm (SD = 7.2). The mean body mass index of the entire cohort was 22.68 kg/m² (SD 2.48) (Table 1). During the second visit, three patients from sequence 1 and two patients from sequence 2 were excluded due to loss of follow-up. Thirty-two patients in the KiwiBiotic group and 33 patients in the psyllium husk group completed the study. At the 5% level of significance, no significant differences were observed between the groups, as P > 0.05.

| Demographics | KiwiBiotic | Psyllium husk | Total | P value |

| Gender | 0.138a | |||

| Female | 25 (71.43) | 19 (54.29) | 44 (62.86) | |

| Male | 10 (28.57) | 16 (45.71) | 26 (37.14) | |

| Age (year) | 0.156 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 41.4 (10.96) | 45.83 (14.84) | 43.61 (13.14) | |

| Range | 18-65 | 23-73 | 18-73 | |

| Weight (kg) | 0.064 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 58.89 (7.88) | 62.41 (8.03) | 60.65 (8.092) | |

| Range | 42-80.9 | 47-79.3 | 42-80.9 | |

| Height (m) | 0.123 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 162.1 (6.68) | 164.73 (7.54) | 163.42 (7.2) | |

| Range | 152-176.7 | 152-177 | 152-177 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.291 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 22.37 (2.40) | 23.00 (2.56) | 22.68 (2.48) | |

| Range | 17.3-28.8 | 17.3-28.3 | 17.3-28.8 |

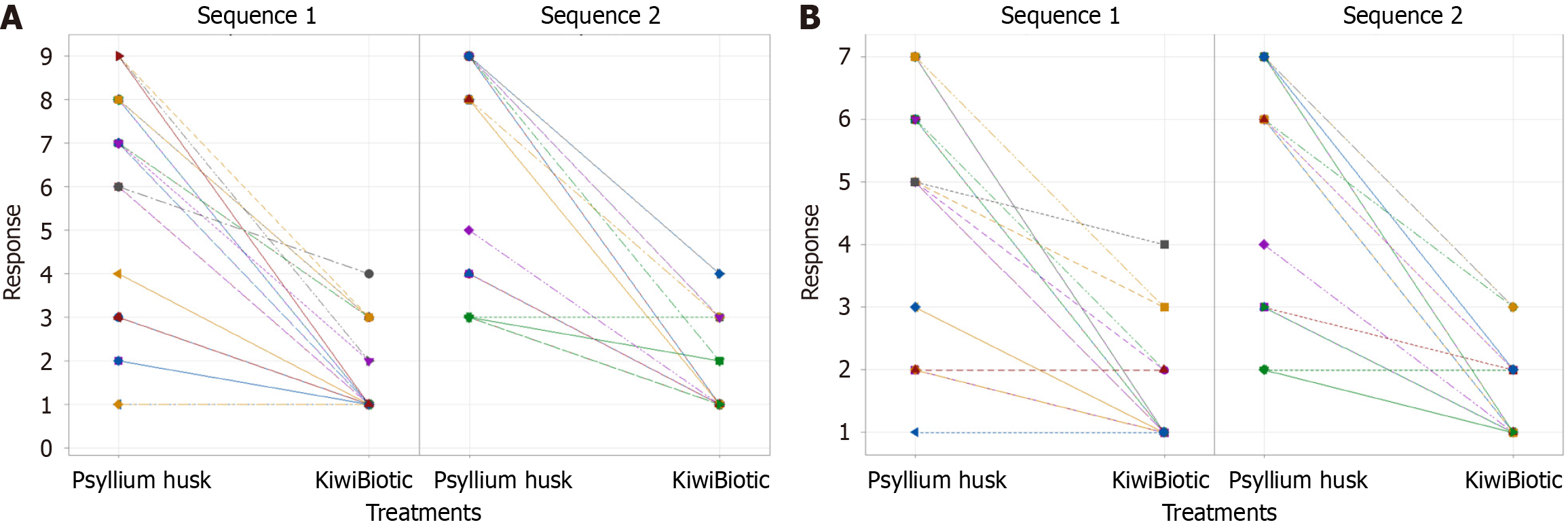

The results showed that for the KP sequence, the mean score of abdominal pain was 1.4688 (SD = 0.87931) at visit 2 in period 1 and 6.2188 (SD = 2.4591) at visit 4 in period 2. In contrast, for the PK sequence, the mean score was 7.2121 (SD = 2.342) at visit 2 in period 1 and 1.6667 (SD = 1.0206) at visit 4 in period 2 (Table 2) (Figure 2A). These findings indicate that KiwiBiotic is more effective than psyllium husk in reducing abdominal pain.

| Sequence | n | Period 1 | Period 2 | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Abdominal pain | KP | 32 | 1.4688 | 0.87931 | 6.2188 | 2.4591 |

| PK | 33 | 7.2121 | 2.342 | 1.6667 | 1.0206 | |

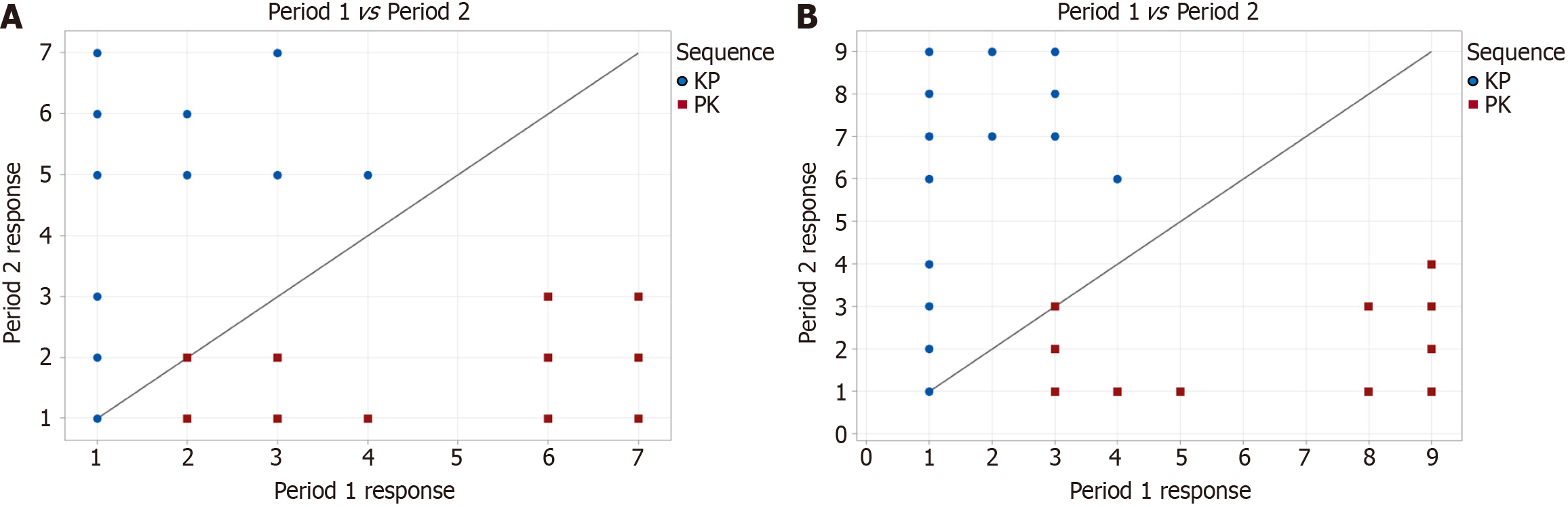

The crossover effect and analysis of abdominal pain showed that the estimated carryover effect was -1.1913 with a corresponding P-value of 0.092, exceeding = 0.05, indicating that the carryover effect was not statistically significant. Conversely, the estimated treatment effect was -5.1477, with a P-value of 0.000, demonstrating statistical significance at the 0.05 level and indicating that one treatment has a superior effect compared to the other. Furthermore, the estimated period effect was -0.39773, but the P-value of 0.175 exceeded = 0.05 (Table 3) (Figure 3A), indicating that the period effect was not statistically significant.

| Effect | SE | DF | T value | P value | 95%CI | Significance | |

| Carryover | -1.1913 | 0.69641 | 63 | -1.7106 | 0.092 | -2.5830, 0.20038 | No |

| Treatment | -5.1477 | 0.28995 | 63 | -17.754 | 0.000 | -5.7271, -4.5683 | Yes |

| Period | -0.39773 | 0.28995 | 63 | -1.3717 | 0.175 | -0.97714, 0.18169 | No |

The findings revealed that the average abdominal bloating score for the KP sequence was 1.3125 (SD = 0.7378) during visit 2 in period 1 and 4.9375 (SD = 1.7949) during visit 4 in period 2. The mean score for sequence PK was 5.4848 (SD = 1.8392) at visit 2 in period 1 and 1.4545 (SD = 0.6657) at visit 4 in period 2 (Figure 2B) (Table 4). Ultimately, these results suggest that KiwiBiotic showed a more substantial improvement in abdominal bloating than psyllium husk.

| Sequence | n | Period 1 | Period 2 | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Abdominal bloating | KP | 32 | 1.3125 | 0.7378 | 4.9375 | 1.7949 |

| PK | 33 | 5.4848 | 1.8392 | 1.4545 | 0.66572 | |

The crossover effect and analysis of abdominal bloating show that the determined carryover effect was -0.68939. However, the P-value (0.178) exceeded = 0.05, indicating a lack of statistical significance for the carryover effect. The estimated treatment effect was -3.8277, with a P-value of 0.000, indicating statistical significance at the 0.05 level. This notable treatment effect implies that one treatment showed superior efficacy over the other. The estimated period effect was -0.20265 with a P-value of 0.382 (Table 5), surpassing = 0.05, making the period effect statistically insignificant.

| Effect | SE | DF | T value | P value | 95%CI | Significance | |

| Carryover | -0.68939 | 0.50583 | 63 | -1.3629 | 0.178 | (-1.7002, 0.32143) | No |

| Treatment | -3.8277 | 0.22994 | 63 | -16.646 | 0.000 | (-4.2872, -3.3681) | Yes |

| Period | -0.20265 | 0.22994 | 63 | -0.88131 | 0.382 | (-0.66216, 0.25686) | No |

A one-sided t-test (5% level of significance) was performed for abdominal pain and abdominal bloating to determine the significant differences between treatments. The mean response to abdominal pain was 1.5692 for KiwiBiotic treatment and 6.7231 for psyllium husk treatment. Similarly, for abdominal bloating, the mean response was 1.3846 for KiwiBiotic treatment and 5.2154 for psyllium husk treatment (Table 6) (Figure 3B). These findings indicate a significant difference between the two treatments (P < 0.05).

| Mean (KiwiBiotic) | Mean (Psyllium husk) | SE | DF | T value | P value | Significance | |

| Abdominal pain | 1.5692 | 6.7231 | 0.28995 | 63 | -17.754 | < 0.05 | Yes |

| Abdominal bloating | 1.3846 | 5.2154 | 0.22994 | 63 | -16.646 | < 0.05 | Yes |

After KiwiBiotic treatment, 39 patients reported no straining, while only one patient experienced the same result after psyllium husk treatment. Regarding the presence of lumpy or hard stool, 39 patients achieved complete relief with KiwiBiotic treatment, compared to only one patient with psyllium husk treatment. Similarly, for the feeling of incomplete evacuation of more than one-fourth (25%) of defecations, 37 patients found complete relief with KiwiBiotic treatment, while only one patient did so with psyllium husk treatment (Table 7).

| Symptoms of functional constipation | Number of subjects experiencing symptom relief from functional constipation after consuming KiwiBiotic but not after psyllium husk | Number of subjects experiencing symptom relief from functional constipation after consuming psyllium husk but not after KiwiBiotic | P value for MC-Nemar’s test |

| Straining during more than ¼ 25% of excretion | 39 | 1 | < 0.05 |

| Lumpy or hard stools (BSFS type 1 or 2) more than 25% of defecations | 39 | 1 | < 0.05 |

| Sensation of incomplete evacuation of more than one-fourth (25%) of defecations | 37 | 1 | < 0.05 |

| Sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage more than ¼ (25%) of defecations | 33 | 0 | < 0.05 |

| Manual manoeuvres to facilitate more than ¼ (25%) of defecation | 33 | 1 | < 0.05 |

| Fewer than three spontaneous bowel movements per week | 11 | 2 | < 0.05 |

In the evaluation of anorectal obstruction or sensation of blockage, nearly 33 patients experienced total relief after KiwiBiotic treatment, while none experienced relief after psyllium husk treatment. Concerning manual maneuvers to facilitate more than 25% defecation, 33 patients achieved complete relief with KiwiBiotic treatment, compared to only one patient with psyllium husk treatment. Similarly, among individuals who experienced fewer than three spontaneous bowel movements per week, 11 patients achieved complete relief with KiwiBiotic treatment, while only one patient reported complete relief with psyllium husk treatment (Table 7).

Rejecting the null hypothesis implies that one treatment is superior because it has more successful patient outcomes. McNemar’s test, which yields a two-sided P-value of < 0.05, for all FC symptoms, rejects the null hypothesis of no difference between treatments with KiwiBiotic and psyllium husk. Consequently, the test results significantly favored KiwiBiotic, as it was more effective in alleviating FC symptoms.

Table 8 indicates that patients treated with KiwiBiotic experienced relief of symptoms that exceeded 90% in various symptoms related to FC, exceeding the relief observed in patients treated with psyllium husk.

| Symptoms of functional constipation | After the KiwiBiotic treatment (%) | After the psyllium husk treatment (%) |

| Straining during more than ¼ 25% of excretion | 91.0 | 32.0 |

| Lumpy or hard stools (BSFS type 1 or 2) more than 25% of defecations | 91.0 | 32.0 |

| Sensation of incomplete evacuation of more than one-fourth (25%) of defecations | 91.0 | 35.0 |

| Sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage more than ¼ (25%) of defecations | 95.0 | 45.0 |

| Manual manoeuvres to facilitate more than ¼ (25%) of defecation | 94.0 | 45.0 |

| Fewer than three spontaneous bowel movements per week | 97.0 | 83.0 |

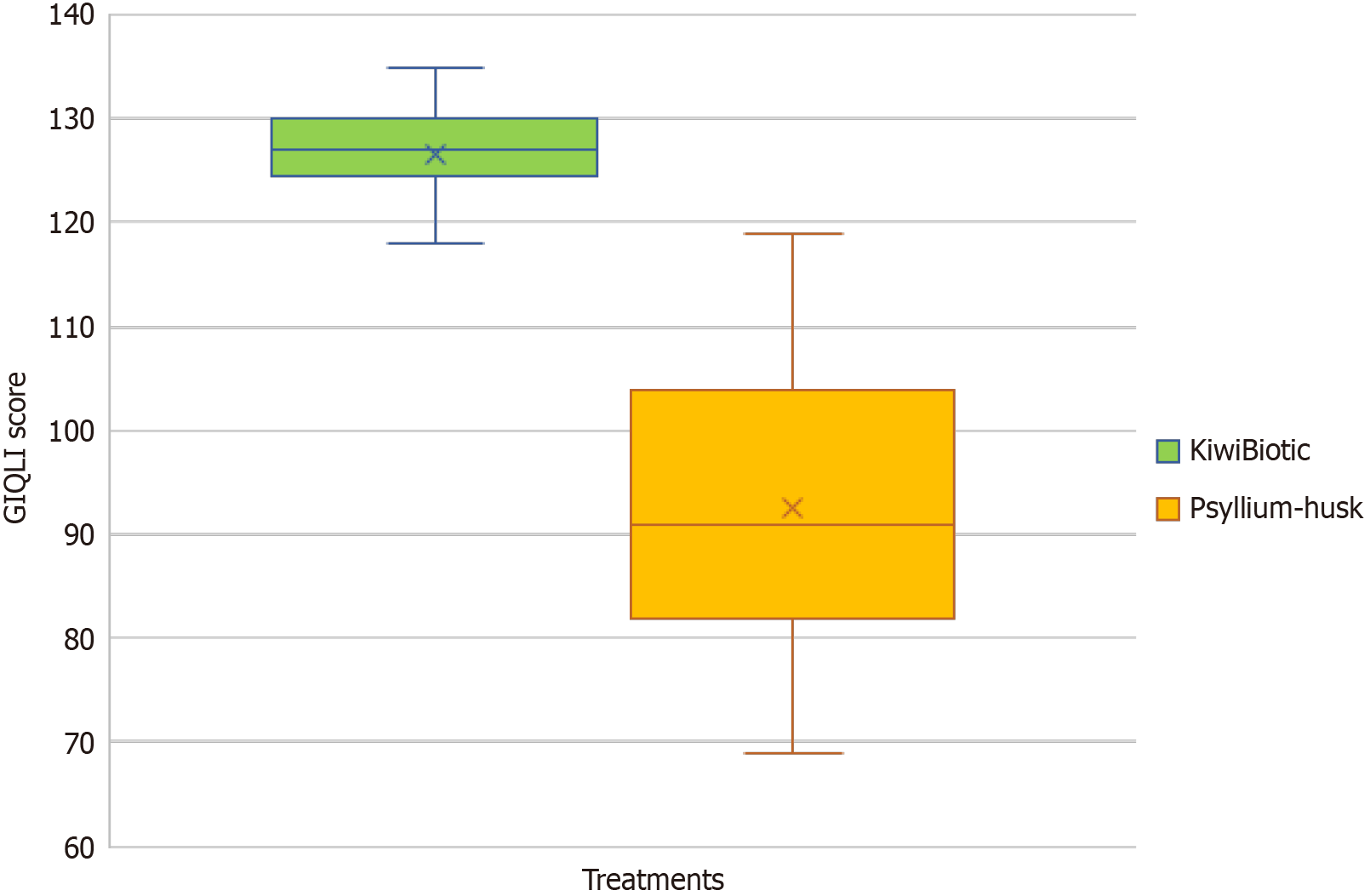

Following treatment with KiwiBiotic, the overall score of the gastrointestinal symptom questionnaire was -39.69 (SD = 6.3), compared to -10.78 (SD = 15.7) after psyllium husk treatment. Regarding the psychological questionnaire, the mean score was -10.19 (SD = 2.2), compared to -0.415 (SD = 5.5) after psyllium husk treatment. After KiwiBiotic treatment, the mean score for the physical questionnaire was -16.71 (SD = 3.3) and for the social questionnaire, it was -2.37 (SD = 3.6). On the contrary, after psyllium husk treatment, the mean scores were -3.23 (SD = 7.1) for the physical questionnaire and -0.077 (SD = 2.0) (Table 9) for the social questionnaire. The overall mean score for the KiwiBiotic treatment was -68.95 (SD = 10.5) and for the psyllium husk treatment, it was -14.51 (SD = 26.8) (Table 9) (Figure 4). These findings suggest that KiwiBiotic generally provides a greater improvement in GIQLI and its domains, such as gastrointestinal symptoms and psychological, physical, and social well-being, compared to psyllium husk treatment, as evidenced by the statistically significant differences in mean scores.

| KiwiBiotic | Psyllium-husk | |||||

| Estimation for paired difference | ||||||

| GIQLI domains | Mean (SD) | 95%CI | P value | Mean (SD) | 95%CI | P value |

| GI-symptoms | -39.69 (6.3) | -41.264, -38.121 | < 0.05 | -10.78 (15.7) | -14.67, -6.90 | < 0.05 |

| Psychological | -10.19 (2.2) | -10.744, -9.626 | < 0.05 | -0.415 (5.5) | -1.787, 0.956 | 0.547 |

| Physical | -16.71 (3.3) | -17.533, -15.883 | < 0.05 | -3.23 (7.1) | -4.999, -1.463 | 0.001 |

| Social | -2.37 (3.6) | -3.262, -1.476 | < 0.05 | -0.077 (2.0) | -0.571, 0.417 | 0.757 |

| Overall | -68.95 (10.5) | -71.56, -66.35 | < 0.05 | -14.51 (26.8) | -21.15, -7.86 | < 0.05 |

Approximately 53.38% of the patients experienced a complete resolution of the condition, 41.54% of the patients reported a significant improvement in their condition, and only 3.08% of the patients reported a slight improvement in their condition after KiwiBiotic treatment (Table 10). Overall, the table shows that a higher percentage of patients experienced positive outcomes, including resolution and significant improvement, when treated with KiwiBiotic than with psyllium Husk.

| Condition | KiwiBiotic (%) | Psyllium-husk |

| Resolved | 55.38 | 0.00 |

| Much better | 41.54 | 9.23 |

| Little better | 3.08 | 13.85 |

| The same | 0.00 | 33.85 |

| Worse | 0.00 | 43.08 |

In this single-center study conducted in a single center, the findings underscore the safety and efficacy of KiwiBiotic in managing symptoms associated with FC, abdominal pain, and bloating compared to psyllium husk. This study revealed significant improvements in various parameters, including symptom relief, quality of life, and overall treatment evaluation, in patients treated with KiwiBiotics. More than 90.0% of the patients experienced symptom relief from FC following treatment with KiwiBiotic. Generally, most of the participants exhibited good tolerance to treatment.

The inherent properties of kiwifruit have shown their effectiveness in reducing symptoms such as constipation, abdominal pain, and discomfort[21-23]. KiwiBiotic contains mainly kiwi pulp and a required quantity of excipients. KiwiBiotic demonstrated a marked decrease in abdominal pain and bloating, supported by notably lower mean scores of 6.2188 and 4.9375, respectively, at visit 4. The analysis of crossover effects indicated statistically significant treatment effects for both abdominal pain and bloating, with a P-value of 0.000 for each, further highlighting the superior efficacy of KiwiBiotic compared to psyllium husk in relieving these symptoms. In the management of FC, more than 90.0% of the patients found relief from symptoms such as straining, lumpy or hard stools, the feeling of incomplete evacuation, the feeling of anorectal obstruction or blockage, the need for manual maneuvers, and fewer than three spontaneous bowel movements per week after treatment with KiwiBiotic. In contrast, after psyllium husk treatment, only 32.0% of the patients experienced relief from straining and lumpy or hard stools, 35.0% from the sensation of incomplete evacuation, 45.0% from the sensation of anorectal obstruction or blockage and the need for manual maneuvers, and 83.0% from fewer than three spontaneous bowel movements per week.

Importantly, the evaluation of GIQLI and its domains revealed that KiwiBiotic significantly improved overall gastrointestinal symptoms, psychological well-being, physical health, and social aspects compared to psyllium husk. These findings underscore the extensive benefits of KiwiBiotic in enhancing the patient’s quality of life beyond symptom relief alone. Furthermore, the overall treatment showed a substantially higher percentage of patients experiencing resolution or significant improvement with KiwiBiotic than with psyllium husk. Collectively, these results suggest that KiwiBiotic is a promising treatment option for managing constipation, abdominal pain, and bloating, offering superior efficacy and patient satisfaction compared to psyllium husk.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that KiwiBiotic is a safe and effective treatment option for managing symptoms of FC, abdominal pain, and bloating. Its superior efficacy, favorable impact on the quality of life, and high patient satisfaction make it a promising alternative to conventional treatments such as psyllium husk. Further research, including larger sample size and long-term follow-up studies, is warranted to validate these findings and establish KiwiBiotics as a standard therapeutic option for individuals with FC and related symptoms.

| 1. | American Gastroenterological Association; Bharucha AE, Dorn SD, Lembo A, Pressman A. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:211-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Diaz S, Bittar K, Hashmi MF, Mendez MD. Constipation. 2023 Nov 12. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Arco S, Saldaña E, Serra-Prat M, Palomera E, Ribas Y, Font S, Clavé P, Mundet L. Functional Constipation in Older Adults: Prevalence, Clinical Symptoms and Subtypes, Association with Frailty, and Impact on Quality of Life. Gerontology. 2022;68:397-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhang C, Jiang J, Tian F, Zhao J, Zhang H, Zhai Q, Chen W. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of the effects of probiotics on functional constipation in adults. Clin Nutr. 2020;39:2960-2969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Koloski NA, Jones M, Wai R, Gill RS, Byles J, Talley NJ. Impact of persistent constipation on health-related quality of life and mortality in older community-dwelling women. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1152-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mugie SM, Benninga MA, Di Lorenzo C. Epidemiology of constipation in children and adults: a systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:3-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 665] [Cited by in RCA: 568] [Article Influence: 40.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schiller LR. Chronic constipation: new insights, better outcomes? Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:873-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vijay Kimtata, Vishu Gupta, Lakhbir Singh, Hasan Ali Ahmed, Ayesha Siddiqua Begum G, A. M. Athar. The Efficacy and Safety of an Ayurvedic Petsaffa Formulation in Subjects with Constipation: An Open-Label, Non-Randomized Clinical Study. Int J Ayu Pharm Res. 2023;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Soliman A, AboAli SEM, Abdel Karim AE, Elsamahy SA, Hasan J, Hassan BA, Mohammed AH. Effect of adding telerehabilitation home program to pharmaceutical treatment on the symptoms and the quality of life in children with functional constipation: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pediatr. 2024;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chang JY, Locke GR 3rd, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Lack of familial aggregation in chronic constipation excluding irritable bowel syndrome: a population-based study. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:1358-1365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Black CJ, Drossman DA, Talley NJ, Ruddy J, Ford AC. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: advances in understanding and management. Lancet. 2020;396:1664-1674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 57.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gallagher P, O'Mahony D. Constipation in old age. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23:875-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rao SS. Constipation: evaluation and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:659-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Marshall JB. Chronic constipation in adults. How far should evaluation and treatment go? Postgrad Med. 1990;88:49-51, 54, 57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fang S, Wu S, Ji L, Fan Y, Wang X, Yang K. The combined therapy of fecal microbiota transplantation and laxatives for functional constipation in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e25390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rao SS, Go JT. Update on the management of constipation in the elderly: new treatment options. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:163-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bongers ME, Benninga MA, Maurice-Stam H, Grootenhuis MA. Health-related quality of life in young adults with symptoms of constipation continuing from childhood into adulthood. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Peng W, Liang H, Sibbritt D, Adams J. Complementary and alternative medicine use for constipation: a critical review focusing upon prevalence, type, cost, and users' profile, perception and motivations. Int J Clin Pract. 2016;70:712-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Aziz I, Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Törnblom H, Simrén M. An approach to the diagnosis and management of Rome IV functional disorders of chronic constipation. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;14:39-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 38.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fawaz SI, Elshatby NM, El-tawab SS. The effect of spinal magnetic stimulation on the management of functional constipation in adults. Egypt Rheumatol Rehabil. 2023;50:17. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bayer SB, Frampton CM, Gearry RB, Barbara G. Habitual Green Kiwifruit Consumption Is Associated with a Reduction in Upper Gastrointestinal Symptoms: A Systematic Scoping Review. Adv Nutr. 2022;13:846-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gearry R, Fukudo S, Barbara G, Kuhn-Sherlock B, Ansell J, Blatchford P, Eady S, Wallace A, Butts C, Cremon C, Barbaro MR, Pagano I, Okawa Y, Muratubaki T, Okamoto T, Fuda M, Endo Y, Kano M, Kanazawa M, Nakaya N, Nakaya K, Drummond L. Consumption of 2 Green Kiwifruits Daily Improves Constipation and Abdominal Comfort-Results of an International Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:1058-1068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Caballero N, Benslaiman B, Ansell J, Serra J. The effect of green kiwifruit on gas transit and tolerance in healthy humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32:e13874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |