Published online Aug 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i8.583

Peer-review started: March 7, 2016

First decision: April 11, 2016

Revised: April 20, 2016

Accepted: May 17, 2016

Article in press: May 27, 2016

Published online: August 27, 2016

Processing time: 174 Days and 11.8 Hours

To analyse the impact of turning of our department from a low to a high volume provider of pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) on surgical outcome.

A retrospective collection of data was done for patients who underwent PD. According to the number of PDs undertaken per year, we categorized the volume into low volume (< 10 PDs/year), medium volume (10-24 PDs/year) and high volume (> 25 PDs/year) groups.

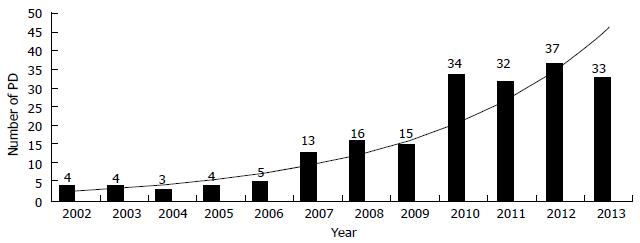

From 2002 to 2013, 200 patients underwent PD. The annual number of PD increased from 4 in 2002 to 34 in 2013. The mean operative time, operative blood loss and need for intraoperative blood transfusion decreased considerably over the volume categories (P < 0.001, P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively). Increased procedural volume was associated with a lower morbidity (P = 0.021) and shorter length of hospital stay (P < 0.001). Similarly the rate of mortality dropped from 10% for the low volume group to 2.2% for the medium volume group and 0.0% for the high volume group (P = 0.007).

The transformation from a low volume to a high volume provider of PD resulted in most favourable outcomes favouring the continued centralization of this high risk procedure.

Core tip: Due to the complexity and challenging nature of pancreaticoduodenectomy, it is likely that both short- and long-term outcomes strongly depend on the cumulative number of cases performed by the surgeon as well as by the hospital. Strong evidence exists for volume-outcome relationship in which high volume centres have reduced perioperative morbidity and mortality. High volume hospitals are assumed to have structural characteristics associated with better quality of care, and providers in these hospitals are thought to improve their processes of care through experience in providing complex care. While the findings of this study are presented in terms of high, medium, and low volume periods, an important point exists regarding the volume-outcome relationship that must be emphasized. Thus for patients seeking to identify a hospital at which to have their surgery, the best strategy if all other factors are equal is to choose the hospital that performs pancreatic surgery most frequently.

- Citation: Shah OJ, Singh M, Lattoo MR, Bangri SA. Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A study from India on the impact of evolution from a low to a high volume unit. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(8): 583-589

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i8/583.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i8.583

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is a complex, high risk surgical procedure usually performed for malignancy of the pancreatic head or periampullary region. Before 1980, PD has been associated with a high rate of morbidity (40%-60%) and a high mortality rate up to 20%[1]. Since that time, the in-hospital mortality rate has decreased substantially with high-volume tertiary care centers reporting in-hospital mortality rate of 4% or less[2,3]. Luft et al[4] provided the empirical relationship between higher surgical volume and lower postoperative mortality, which led to centralization of high risk operations to improve the outcome. Various studies have demonstrated that high volume tertiary centers have significantly lower (< 5%) in-hospital mortality rates for PD than low volume centres (> 10%)[5,6]. The majority of data regarding centralization of PD were obtained from multi-institutional comparisons and there are few studies describing the effects of increased caseload of PD within the same unit. Although the trend of centralization has been slow as demonstrated by a nationwide survey of PD in the United States[7], no information is available regarding volume-outcome association in India.

The purpose of this study was to explore the effect of centralization of PD on perioperative outcome at a tertiary care center in Northern India during the period 2002-2013 and analyse the impact of turning our department from a low to a high volume provider of PD.

Through retrospective collection of data from a prospectively maintained database at the Department of Surgical Gastroenterology, Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Kashmir (India), medical records of patients who underwent PD for pancreatic or periampullary benign or malignant lesions were identified. Patient’s demographics, surgical parameters and postoperative events were recorded and analysed. After performing PD (classical or pylorus preserving) with or without associated organ resection, pancreaticojejunostomy was achieved by anastomosing the pancreatic remnant to the end of the jejunal loop by either mucosa to mucosa or dunking method. All the surgical procedures were performed by the senior surgeon OJS with a senior assistant (SAB). The present study also included patients who were a part of previous publications from the department[8-10]. Clavien-Dindo classification[11] was used to grade the complications, and complications requiring either intervention under local or locoregional or general anaesthesia, ICU management or causing death were considered as major (grades 3-5). Besides recording the annual departmental volume, according to the number of PD performed per year we categorized the volume into low volume (< 10 PDs/year); medium volume (10-24 PDs/year; and high volume (≥ 25 PDs/year) as described earlier[12].

Pancreatic fistula was categorized according to the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula criteria[13]. Inability of a patient to return to a standard diet by the end of the first postoperative week necessitating prolonged nasogastric intubation of the patient was treated as delayed gastric emptying (DGE) as defined by the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS)[14], bile leak was defined as bilious drain with raised bilirubin level, and culture positive purulent collection was treated as intra-abdominal abscess.

Postpancreatectomy haemorrhage (PPH) was defined according to the ISGPS based on the time of onset, site of bleeding, severity and clinical impact[15]. Overall morbidity included all major complications including infections, cardiopulmonary and gastrointestinal complications; the primary endpoint was operative mortality defined as death occurring during the period of hospital stay or within 30 d of surgery. Secondary endpoints were postoperative morbidity rate, occurrence of pancreatic fistula, DGE and length of hospital stay. Follow-up for infection and non-infectious complications was carried out for 30 d after hospital discharge. Readmission rate (within 30 d after discharge) was also recorded.

Statistical analyses were performed using χ2 and Fishers exact tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. Post hoc tests were applied to look for inter-group differences. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20 Chicago (United States). P values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant.

During the 12-year period from January 2002 to December 2013, 200 PDs were performed in the department. Across the study period, the annual average number of PD increased from 4 in 2002 to 34 in 2013 (Figure 1). The most common indications for surgery were pancreatic adenocarcinoma (n = 85, 42.5%), ampullary adenocarcinoma (n = 57, 28.5%) and distal cholangiocarcinoma (n = 23, 11.5%) (Table 1). The various demographic features between the low volume (group A), medium volume (group B) and high volume (group C) categories revealed no statistical change during the study period (Table 2). In group C, PD included portal vein resection (4 patients) and right hemicolectomy (6 patients) (Table 3).

| Variable | n (%) |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | 85 (42.5) |

| Ampullary adenocarcinoma | 57 (28.5) |

| Distal cholangiocarcinoma | 23 (11.5) |

| Duodenal adenocarcinoma | 10 (5.0) |

| Neuroendocrine tumors | 7 (3.5) |

| Serous cystadenoma | 3 (1.5) |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 3 (1.5) |

| Mucinous cystadenoma | 2 (1.0) |

| Intra-ductal papillary mucinous neoplasm | 2 (1.0) |

| Pancreatoblastoma | 2 (1.0) |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumors | 2 (1.0) |

| Pancreatic sarcoma | 1 (0.5) |

| Duodenal leiomyoma | 1 (0.5) |

| Angiomyolipoma | 1 (0.5) |

| Mucinous cystoadenocarcinoma | 1 (0.5) |

| Variable | Low volume (< 10 PDs/yr), n = 20 | Medium volume (10-24 PDs/yr), n = 44 | High volume (≥ 25 PDs/yr), n = 136 | P value |

| Gender (male/female) | 12/8 | 25/19 | 80/56 | 0.963 |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 58.95 ± 10.44 | 59.22 ± 10.29 | 62.58 ± 9.05 | 0.059 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 21.00 ± 2.55 | 21.59 ± 2.76 | 21.45 ± 2.50 | 0.691 |

| ASA score, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 3 (15.0) | 6 (13.6) | 16 (11.8) | |

| 2 | 12 (60.0) | 26 (59.2) | 78 (57.4) | |

| 3 | 4 (20.0) | 10 (22.7) | 34 (25.0) | 0.996 |

| 4 | 1 (50.0) | 2 (4.5) | 8 (5.8) | |

| Jaundice, n (%) | 16 (80.0) | 32 (72.7) | 105 (77.2) | 0.770 |

| Abdominal pain, n (%) | 7 (35.0) | 15 (34.1) | 40 (29.4) | 0.776 |

| Vomiting, n (%) | 4 (20.0) | 7 (15.9) | 24 (17.6) | 0.920 |

| Cholangitis, n (%) | 3 (15.0) | 6 (13.6) | 26 (19.1) | 0.674 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 3 (15.0) | 9 (20.5) | 23 (16.9) | 0.825 |

| CV disease, n (%) | 3 (15.0) | 7 (15.9) | 18 (13.2) | 0.898 |

| Cold, n (%) | 2 (10.0) | 4 (9.1) | 8 (5.9) | 0.659 |

| Preoperative Hb (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 9.37 ± 1.19 | 9.73 ± 1.44 | 9.62 ± 1.19 | 0.558 |

| Preoperative albumin (mg/dL) | 3.33 ± 0.52 | 3.52 ± 0.58 | 3.56 ± 2.68 | 0.914 |

| Serum bilirubin (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 9.48 ± 5.38 | 8.56 ± 4.00 | 9.11 ± 5.38 | 0.754 |

| Preoperative biliary stenting, n (%) | 3 (15.0) | 8 (18.2) | 19 (14.0) | 0.794 |

| Variable | Low volume (< 10 PDs/yr), n = 20 | Medium volume (10-24 PDs/yr), n = 44 | High volume (≥ 25 PDs/yr), n = 136 |

| Preoperative | |||

| Triple phase CECT abdomen/pelvis | 10 (50) | 40 (90.9) | 136 (100) |

| CA 19.9 | 10 (50) | 44 (100) | 136 (100) |

| Operative | |||

| Classical Whipple | 14 (70) | 12 (27.3) | 4 (2.9) |

| PPPD | 6 (30) | 32 (72.7) | 132 (97.1) |

| With portal vein resection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (2.9) |

| With right hemicolectomy | 0 (0) | 2 (4.5) | 6 (4.4) |

| Pancreaticojejunostomy | |||

| Duct to mucosa | 17 (85) | 5 (11.4) | 0 (0) |

| Dunking | 3 (15) | 39 (88.6) | 136 (100) |

| Use of pyloric dilatation | 0 (0) | 32 (72.7) | 132 (97.1) |

| Use of omental flap[8] | 0 (0) | 10 (22.7) | 136 (100) |

| No of abdominal drains | |||

| 1 drain | 4 (20) | 39 (88.6) | 136 (100) |

| 2 drains | 16 (80) | 5 (11.4) | 0 (0) |

| Feeding jejunostomy | 15 (75) | 26 (59.1) | 10 (7.4) |

| Octreotide 0.1 mg S/C × 3 times for 1 wk | 15 (75) | 10 (22.7) | 0 (0) |

| Postoperative | |||

| Fast track approach[10] | 0 (0) | 16 (36.4) | 126 (92.6) |

In groups A, B and C the mean duration of surgery (246.3 ± 20.6 min, 227.7 ± 47.5 min, 125.5 ± 16.1 min, P≤ 0.001), operative blood loss (1098.5 ± 163.8 mL, 932.3 ± 207.5 mL, 415.9 ± 82.7 mL, P≤ 0.001), mean blood units transfused (1.3 ± 0.4 UI, 1.3 ± 0.6 UI, 0.2 ± 0.4 UI, P≤ 0.001) and the requirement of feeding jejunostomy (75%, 59.1%, 7.4%, P≤ 0.001) decreased significantly with increasing hospital volume (Table 4). There was a progressive regression in the rate of overall complications across the volume groups (group A, 50.0%; group B, 45.5% and group C, 27.2%, P = 0.021).

| Variable | Low volume (< 10 PDs/yr), n = 20 | Medium volume (10-24 PDs/yr), n = 44 | High volume (≥ 25 PDs/yr), n = 136 | P value |

| Duration of surgery in minutes, mean ± SD | 246.3 ± 20.6 | 227.7 ± 47.5 | 125.5 ± 16.1 | < 0.001 |

| Operative blood loss in millilitre, mean ± SD | 1098.5 ± 163.8 | 932.3 ± 207.5 | 415.9 ± 82.7 | < 0.001 |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion required, no of patients (%) | 20 (100) | 41 (93.2) | 23 (16.9) | < 0.001 |

| Mean blood units transfused, mean ± SD | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 0.2 ± 0.4 (0-1) | < 0.001 |

| Pancreatic texture, n (%) | ||||

| Soft | 4 (20.0) | 11 (25.0) | 30 (22.1) | |

| Intermediate | 11 (55.0) | 20 (45.5) | 72 (52.9) | 0.925 |

| Firm | 5 (25.0) | 13 (29.5) | 34 (25.0) | |

| Pancreatic duct diameter at neck, n (%) | ||||

| < 3 mm | 7 (35.0) | 12 (27.3) | 46 (33.8) | 0.700 |

| ≥ 3 mm | 13 (65.0) | 32 (72.7) | 90 (66.2) | |

| Feeding jejunostomy, n (%) | 15 (75.0) | 26 (59.1) | 10 (7.4) | < 0.001 |

The most common complications were DGE and occurrence of pancreatic fistula. Both these types of complications showed a significant difference in rates across the volume groups (pancreatic fistula rate of 15.0% in group A, 15.9% in group B and 3.6% in group C; P = 0.011), whereas DGE was observed at a rate of 20.0% in group A; 18.2% in group B and 5.9% in group C (P = 0.018; Table 5). The rate of PPH was 10.0% in group A; 2.2% in group B and 0% in group C (P = 0.007; Table 4). Five patients required reoperative surgery (2 postoperative haemorrhage, 2 pancreatic fistula and 1 DGE). The reoperative rate significantly decreased when comparing the volume groups (in low volume 10.0%; in medium volume 4.5% and in high volume 0.7%, P = 0.029). Occurrence of intraabdominal infections and rate of bile leak also decreased when comparing the volume categories, but did not reach statistical significance.

| Variable | Low volume (< 10 PDs/yr), n = 20 | Medium volume (10-24 PDs/yr), n = 44 | High volume (≥ 25 PDs/yr), n = 136 | P value |

| Pancreatic fistula, n (%) | 3 (15.0) | 7 (15.9) | 5 (3.6) | |

| Grade A | 1 (33.3) | 3 (42.8) | 2 (40.0) | 0.011 |

| Grade B | 1 (33.3) | 3 (42.8) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Grade C | 1 (33.3) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Delayed gastric emptying, n (%) | 4 (20.0) | 8 (18.2) | 8 (5.9) | |

| Grade A | 2 | 6 | 7 | |

| Grade B | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.018 |

| Grade C | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hemorrhage, n (%) | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Grade A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.007 |

| Grade B | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Grade C | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Intra-abdominal infection, n (%) | 1 (5.0) | 2 (4.5) | 1 (0.7) | 0.175 |

| Bile leak, n (%) | 1 (5.0) | 2 (4.5) | 2 (1.5) | 0.395 |

| Total morbidity, n (%) | 10 (50.0) | 20 (45.5) | 37 (27.2) | 0.021 |

| Major morbidity (Clavien grade III, IV) | 3 (15.0) | 2 (4.5) | 3 (2.2) | 0.024 |

| Reoperation, n (%) | 2 (10.0) | 2 (4.5) | 1 (0.7) | 0.029 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 2 (10) | 1 (2.2) | 0 | 0.007 |

| Postoperative length of hospital stay (d), mean ± SD | 11.8 ± 3.4 | 11.3 ± 2.9 | 7.9 ± 1.7 | < 0.001 |

A consistent decrease in the mean length of hospital stay was noticed for the high volume group of patients and differences across groups were statistically significant (11.8 ± 3.4 d, 11.3 ± 2.9 d and 7.9 ± 1.7 d for low, medium and high volume periods, respectively; P≤ 0.001). The consistency of the stepwise inverse relation between volume and in-hospital mortality was notable (0%, 2.2% and 10.0% for high, medium and low volume groups, respectively).

More than 30 years ago, Luft et al[4] introduced the empirical relationship between higher surgical volume and lower postoperative mortality. This led to the concept of centralization of complex surgical procedures to improve outcome. This relationship of hospital volume and surgical mortality for complex surgical procedures including PD was amply described by Birkmeyer et al[16]. Despite improvements due to regionalization, PD remains a complex procedure associated with high perioperative morbidity and potential mortality. Strong evidence exists for volume-outcome relationship where high volume centers have reduced perioperative morbidity and mortality, although the exact mechanism (surgeon related factors vs system related factors) behind it remains unclear. For example, an experienced surgeon working in a low volume institution may be technically proficient at PD; however, the system support for diagnosis and treatment of postoperative complications may be inadequate. Conversely a high volume center with intensive care, interventional radiologic and gastroenterological expertise could provide superior support to a surgeon with lesser PD experience. Previous publications have clearly demonstrated that mortality, survival and overall life expectancy are improved when PD is performed in high volume centers[17-20].

SKIMS is the only tertiary care hospital available for the population (about 10 million) of Kashmir valley. SKIMS, the regional provider, developed interest in the PD procedure and developed a focussed team dedicated to caring for these patients. This included formulation of treatment protocols and critical care ways, as well as standardizing diagnostic workups, operative details and management of postoperative complications. Further information regarding provider capabilities and surgical results were disseminated locally, regionally and nationally. This resulted in an increased number of referrals to the institution, resulting in regionalization. In the first period of the study (January 2002 to September 2006), the annual average number of PD was about 4. It went up to 14/year in the next three and a half years, and in the last phase of this study the figure was 34. There was a significant drop in the operative parameters like operative time (246.3 ± 20.6 min, 227.7 ± 47.5 min to 125.5 ± 16.1 min, P≤ 0.001), operative blood loss (1098.5 ± 163.8 to 932.3 ± 207.5 mL to 415.9 ± 82.7 mL, P≤ 0.001), requirement and mean blood units transfused (1.3 ± 0.4 UI to 1.3 ± 0.6 UI to 0.2 ± 0.4 UI, P≤ 0.001). Similarly the occurrence of complications like pancreatic fistula (15.0% to 15.9% to 3.6%, P = 0.011), DGE (20.0% to 18.2% to 5.9%, P = 0.018) and PPH (10% to 2.2% to 0%, P = 0.007) decreased significantly with the increase in procedure volume and increased experience.

Surgeon volume has been less emphasized in the literature and until more recently, it has been linked to mortality and may explain a significant part of an institution’s volume effect[21]. A learning curve in pancreatic surgery has been hypothesized and modelled, suggesting that after 60 PDs surgeons improved the perioperative outcomes of estimated blood loss, operative time and length of hospital stay in patients undergoing PD for periampullary adenocarcinoma[22]. Few elective surgical procedures are associated with higher operative risk.

Numerous studies show a consistent trend towards hospital case volume predicting better outcome in pancreatic surgery. These studies offer the most compelling support of the hospital case volume: Better outcome concept because of their size and diversity of the study design. In 1995 Gordon et al[23] published a retrospective study on 501 patients who underwent pancreatic resection at one of 39 hospitals in Maryland. Hospital mortality rate was significantly lower at the high-volume regional medical center compared to all other hospitals (2.2% vs 13.5%).

The persistent increase in the number of PD not only resulted in gross reduction of overall morbidity (50.0% to 45.5% to 27.2%, P = 0.021), but also significantly decreased the length of hospital stay (11.8 ± 3.4 d to 11.3 ± 2.9 to 7.9 ± 1.7, P = 0.001). It is worth to mention that hospitals with 11 years of experience performing one Whipple’s procedure per year have a predicted mortality rate that is lower than for very low volume hospitals with only 1 year of experience, although the difference is not statistically significant. Moreover, very low volume hospitals with 11 years of experience have a predicted mortality rate that is significantly different and almost three times higher than that for hospitals with 11 years of experience that perform 10 or more Whipple’s procedures per year (9.2% vs 3.4%)[17]. Thus experience does little to mitigate the difference in mortality observed between low and high volume hospitals. During the time of the study, the mortality rate dropped significantly from 10% to 0%. These results suggest that achieving a procedure volume of 25 PDs or more per year may be sufficient for minimizing inpatient mortality. The influence of institutional volume has also been reflected on late survival after PD for cancer. Birkmeyer et al[24] investigated this possible effect and concluded higher 3-year survival rate at high volume hospitals (37%) than at those with medium (29%), low (26%) or very low volume (25%) (P < 0.0001). These findings indicate that hospital volume also influences both perioperative risk and long-term survival after PD for cancer.

It has been clearly stated that the volume-outcome relationship usually is stronger for hospital volume than for surgeon volume. This has been ascribed to the “experience effect” of the whole team taking care of the patient. There are two competing explanations for the observed association between volume and outcome. The first, “practice makes perfect”, hypothesizes that institutions have better outcome because their case load and experience allow them to improve their systems and techniques. The second, “selective referral”, hypothesizes that institutions with better outcomes have larger volumes because their excellence is known and thus more patients come to be cared for in these institutions. Which hypothesis is correct has not been established.

This study clearly demonstrates that regionalization can benefit the population of a state through the reduction of in-hospital mortality. In spite of the fact that this study was not able to examine the functional status, quality of life or the length of survival, in-hospital mortality rate is an important objective measurement and of great interest and concern to consumers. Although this study has several possible limitations like the retrospective nature, lack of information on cancer staging, unavailability of data on quality of life and long term survival, the major strength of this study is that volume groups were compared within the same surgical unit and this eliminates several biased variables affecting inter-hospital comparisons. Further individual patient variables and clinical course which previous volume outcome studies lack were described based on administrative data and not medical records. The results of this study support the beneficial effects of regionalization by which health care services should result in optimization of outcomes for complex, high risk elective surgeries. Further research should be directed to identify procedures for which regionalization is most likely to have a beneficial effect and to determine how best to achieve the regionalization.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is a complex, high risk surgical procedure usually performed for malignancy of the pancreatic head or periampullary region. PD has been associated with a high rate of morbidity (40%-60%) and a high mortality rate up to 20%. High volume tertiary centers have significantly lower (< 5%) in-hospital mortality rates for PD than low volume centres (> 10%). This led to the concept of centralization of complex surgical procedures to improve outcome.

The purpose of this study was to explore the effect of centralization of PD on perioperative outcome at a tertiary care center in Northern India during the period 2002-2013 and analyse the impact of turning the authors’ department from a low to a high volume provider of PD. Although the trend of centralization has been slow as demonstrated by a nationwide survey of PD in the United States, no information is available regarding volume outcome association in India.

It has been clearly stated that the volume-outcome relationship usually is stronger for hospital volume than for surgeon volume. This has been ascribed to the “experience effect” of the whole team taking care of the patient. High volume hospitals are assumed to have structural characteristics associated with better quality of care, and providers in these hospitals are thought to improve their processes of care through experience in providing complex care. While the findings of this study are presented in terms of high, medium, and low-volume periods, an important point exists regarding the volume-outcome relationship that must be emphasized.

The results of this study support the beneficial effects of regionalization by which health care services should result in optimization of outcomes for complex, high risk elective surgeries. Further research should be directed to identify procedures for which regionalization is most likely to have a beneficial effect and to determine how best to achieve the regionalization.

PD is associated with a high morbidity and mortality and a constant effort at improving this, among many, has led to the concept of centralization. The concept of centralization stresses the importance of high volume centers that are assumed to have structural characteristics associated with better quality of care, and providers in these hospitals are thought to improve their processes of care through experience in providing complex care.

The majority of data regarding centralization of PD are obtained from multi-institutional comparisons and there are few studies describing the effects of increased caseload of PD within the same unit. Numerous studies show a consistent trend towards hospital case volume predicting better outcome in pancreatic surgery. These studies offer the most compelling support of the hospital case volume: Better outcome concept because of their size and diversity of the study design. In India no information is available regarding volume outcome association.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Fu DL, Joliat GR, Zhang XB S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Cameron JL, Riall TS, Coleman J, Belcher KA. One thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. Ann Surg. 2006;244:10-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 896] [Cited by in RCA: 968] [Article Influence: 50.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 2. | Lieberman MD, Kilburn H, Lindsey M, Brennan MF. Relation of perioperative deaths to hospital volume among patients undergoing pancreatic resection for malignancy. Ann Surg. 1995;222:638-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 409] [Cited by in RCA: 419] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 3. | Gordon TA, Burleyson GP, Tielsch JM, Cameron JL. The effects of regionalization on cost and outcome for one general high-risk surgical procedure. Ann Surg. 1995;221:43-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Luft HS, Bunker JP, Enthoven AC. Should operations be regionalized? The empirical relation between surgical volume and mortality. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:1364-1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1231] [Cited by in RCA: 1230] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Balzano G, Zerbi A, Capretti G, Rocchetti S, Capitanio V, Di Carlo V. Effect of hospital volume on outcome of pancreaticoduodenectomy in Italy. Br J Surg. 2008;95:357-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Birkmeyer JD, Finlayson SR, Tosteson AN, Sharp SM, Warshaw AL, Fisher ES. Effect of hospital volume on in-hospital mortality with pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery. 1999;125:250-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 372] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Learn PA, Bach PB. A decade of mortality reductions in major oncologic surgery: the impact of centralization and quality improvement. Med Care. 2010;48:1041-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shah OJ, Bangri SA, Singh M, Lattoo RA, Bhat MY. Omental flaps reduces complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2015;14:313-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Shah OJ, Robbani I, Shah P, Bangri SA, Khan IJ, Bhat MY, Singh M. A selective approach to the surgical management of periampullary cancer patients and its outcome. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2014;13:628-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shah OJ, Bangri SA, Singh M, Lattoo RA. The Impact of Fast Track strategy on centralization of Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A comparative study from India. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2016;In press. |

| 11. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 24805] [Article Influence: 1181.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gouma DJ, van Geenen RC, van Gulik TM, de Haan RJ, de Wit LT, Busch OR, Obertop H. Rates of complications and death after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and the impact of hospital volume. Ann Surg. 2000;232:786-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 619] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3282] [Cited by in RCA: 3512] [Article Influence: 175.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 14. | Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Traverso LW. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2007;142:761-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1771] [Cited by in RCA: 2327] [Article Influence: 129.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery. 2007;142:20-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1411] [Cited by in RCA: 1944] [Article Influence: 108.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, Batista I, Welch HG, Wennberg DE. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128-1137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3695] [Cited by in RCA: 3771] [Article Influence: 164.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ho V, Heslin MJ. Effect of hospital volume and experience on in-hospital mortality for pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2003;237:509-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Topal B, Van de Sande S, Fieuws S, Penninckx F. Effect of centralization of pancreaticoduodenectomy on nationwide hospital mortality and length of stay. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1377-1381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kotwall CA, Maxwell JG, Brinker CC, Koch GG, Covington DL. National estimates of mortality rates for radical pancreaticoduodenectomy in 25,000 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:847-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fong Y, Gonen M, Rubin D, Radzyner M, Brennan MF. Long-term survival is superior after resection for cancer in high-volume centers. Ann Surg. 2005;242:540-544; discussion 544-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Eppsteiner RW, Csikesz NG, McPhee JT, Tseng JF, Shah SA. Surgeon volume impacts hospital mortality for pancreatic resection. Ann Surg. 2009;249:635-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tseng JF, Pisters PW, Lee JE, Wang H, Gomez HF, Sun CC, Evans DB. The learning curve in pancreatic surgery. Surgery. 2007;141:456-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gordon TA, Bowman HM, Tielsch JM, Bass EB, Burleyson GP, Cameron JL. Statewide regionalization of pancreaticoduodenectomy and its effect on in-hospital mortality. Ann Surg. 1998;228:71-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Birkmeyer JD, Warshaw AL, Finlayson SR, Grove MR, Tosteson AN. Relationship between hospital volume and late survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery. 1999;126:178-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |